6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Open Book Publishers

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

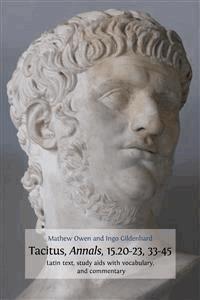

The emperor Nero is etched into the Western imagination as one of ancient Rome’s most infamous villains, and Tacitus’ Annals have played a central role in shaping the mainstream historiographical understanding of this flamboyant autocrat. This section of the text plunges us straight into the moral cesspool that Rome had apparently become in the later years of Nero’s reign, chronicling the emperor’s fledgling stage career including his plans for a grand tour of Greece; his participation in a city-wide orgy climaxing in his publicly consummated ‘marriage’ to his toy boy Pythagoras; the great fire of AD 64, during which large parts of central Rome went up in flames; and the rising of Nero’s ‘grotesque’ new palace, the so-called ‘Golden House’, from the ashes of the city. This building project stoked the rumours that the emperor himself was behind the conflagration, and Tacitus goes on to present us with Nero’s gruesome efforts to quell these mutterings by scapegoating and executing members of an unpopular new cult then starting to spread through the Roman empire: Christianity. All this contrasts starkly with four chapters focusing on one of Nero’s most principled opponents, the Stoic senator Thrasea Paetus, an audacious figure of moral fibre, who courageously refuses to bend to the forces of imperial corruption and hypocrisy. This course book offers a portion of the original Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and a commentary. Designed to stretch and stimulate readers, Owen’s and Gildenhard’s incisive commentary will be of particular interest to students of Latin at both A2 and undergraduate level. It extends beyond detailed linguistic analysis and historical background to encourage critical engagement with Tacitus’ prose and discussion of the most recent scholarly thought.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

TACITUS, ANNALS, 15.20–23, 33–45

Tacitus, Annals, 15.20–23, 33–45

Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary

Mathew Owen and Ingo Gildenhard

http://www.openbookpublishers.com

© 2013 Mathew Owen and Ingo Gildenhard

This book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported licence (CC-BY 3.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work; to adapt the work and to make commercial use of the work providing attribution is made to the authors (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information:

Owen, Mathew and Gildenhard, Ingo. Tacitus, Annals, 15.20–23, 33–45. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2013. DOI: 10.11647/OBP.0035

Further details about CC-BY licences are available at:

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/

Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available on our website at: http://www.openbookpublishers.com/isbn/9781783740000

ISBN Hardback: 978-1-78374-001-7

ISBN Paperback: 978-1-78374-000-0

ISBN Digital (PDF): 978-1-78374-002-4

ISBN Digital ebook (epub): 978-1-78374-003-1

ISBN Digital ebook (mobi): 978-1-78374-004-8

DOI: 10.11647/OBP.0035

Cover image: Bust of Nero, the Capitoline Museum, Rome (2009) © Joe Geranio (CC-BY-SA-3.0), Wikimedia.org.

All paper used by Open Book Publishers is SFI (Sustainable Forestry Initiative), and PEFC (Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification Schemes) Certified.

Printed in the United Kingdom and United States by Lightning Source for Open Book Publishers (Cambridge, UK).

Contents

1. Preface and acknowledgements

2. Introduction

2.1 Tacitus: life and career

2.2 Tacitus’ times: the political system of the principate

2.3 Tacitus’ oeuvre: opera minora and maiora

2.4 Tacitus’ style (as an instrument of thought)

2.5 Tacitus’ Nero-narrative: Rocky-Horror-Picture Show and Broadway on the Tiber

2.6 Thrasea Paetus and the so-called ‘Stoic opposition’

3. Latin text with study questions and vocabulary aid

4. Commentary

Section 1: Annals 15.20–23

(I) 20.1–22.1: The Meeting of the Senate

(II) 22.2: Review of striking prodigies that occurred in AD 62

(III) 23.1–4: Start of Tacitus’ account of AD 63: the birth and death of Nero’s daughter by Sabina Poppaea, Claudia Augusta

Section 2: Annals 15.33–45 (AD 64)

(I) 33.1–34.1: Nero’s coming-out party as stage performer

(II) 34.2–35.3: A look at the kind of creatures that populate Nero’s court – and the killing of an alleged rival

(III) 36: Nero considers, but then reconsiders, going on tour to Egypt

(IV) 37: To show his love for Rome, Nero celebrates a huge public orgy that segues into a mock-wedding with his freedman Pythagoras

(V) 38–41: The fire of Rome

(VI) 42–43: Reconstructing the Capital: Nero’s New Palace

(VII) 44: Appeasing the Gods, and Christians as Scapegoats

(VIII) 45: Raising of Funds for Buildings

5. Bibliography

6. Visual aids

6.1 Map of Italy

6.2 Map of Rome

6.3 Family Tree of Nero and Junius Silanus

6.4 Inside the Domus Aurea

1. Preface and acknowledgements

The selective sampling of Latin authors that the study of set texts at A-level involves poses four principal challenges to the commentators. As we see it, our task is to: (i) facilitate the reading or translation of the assigned passage; (ii) explicate its style and subject matter; (iii) encourage appreciation of the extract on the syllabus as part of wider wholes – such as a work (in our case the Annals), an oeuvre (here that of Tacitus), historical settings (Neronian and Trajanic Rome), or a configuration of power (the principate); and (iv) stimulate comparative thinking about the world we encounter in the assigned piece of Latin literature and our own. The features of this textbook try to go some way towards meeting this multiple challenge:

To speed up comprehension of the Latin, we have given a fairly extensive running vocabulary for each chapter of the text, printed on the facing page. We have not indicated whether or not any particular word is included in any ‘need to know’ list; and we are sure that most students will not require as much help as we give. Still, it seemed prudent to err on the side of caution. We have not provided ‘plug in’ formulas in the vocabulary list: but we have tried to explain all difficult grammar and syntax in the commentary. In addition, the questions on the grammar and the syntax that follow each chapter of the Latin text are designed, not least, to flag up unusual or difficult constructions for special attention. Apart from explicating grammar and syntax, the commentary also includes stylistic and thematic observations, with a special emphasis on how form reinforces, indeed generates, meaning. We would like to encourage students to read beyond the set text and have accordingly cited parallel passages from elsewhere in the Annals or from alternative sources, either in Latin and English or, when the source is in Greek, in English only. Unless otherwise indicated, we give the text and translation (more or less modified) according to the editions in the Loeb Classical Library. Our introduction places Tacitus and the set text within wider historical parameters, drawing on recent – and, frequently, revisionist – scholarship on imperial Rome: it is meant to provoke, as well as to inform. Finally, for each chapter of the Latin text we have included a ‘Stylistic Appreciation’ assignment and a ‘Discussion Point’: here we flag up issues and questions, often with a contemporary angle, that lend themselves to open-ended debate, in the classroom and beyond.

* * *

We would like to thank the team at Open Book Publishers, and in particular Alessandra Tosi, for accepting this volume for publication, speeding it through production – and choosing the perfect reader for the original manuscript: connoisseurs of John Henderson’s peerless critical insight will again find much to enjoy in the following pages (acknowledged and unacknowledged), and we are tremendously grateful for his continuing patronage of, and input into, this series.

2. Introduction

DOI: 10.11647/OBP.0035.01

At the outset of his Annals, which was his last work, published around AD 118, Tacitus states that he wrote sine ira et studio (‘without anger or zeal’), that is, in an objective and dispassionate frame of mind devoted to an uninflected portrayal of historical truth. The announcement is part of his self-fashioning as a muckraker above partisan emotions who chronicles the sad story of early imperial Rome: the decline and fall of the Julio-Claudian dynasty (AD 14–68) in the Annals and the civil war chaos of the year of the four emperors (AD 69) followed by the rise and fall of the Flavian dynasty (AD 69–96) in the (earlier) Histories. But his narrative is far from a blow-by-blow account of Roman imperial history, and Tacitus is an author as committed as they come – a literary artist of unsparing originality who fashions his absorbing subject matter into a dark, defiant, and deadpan sensationalist vision of ‘a world in pieces’, which he articulates, indeed enacts, in his idiosyncratic Latinity.1 To read this Latin and to come to terms with its author is not easy: ‘No one else ever wrote Latin like Tacitus, who deserves his reputation as the most difficult of Latin authors.’2

This introduction is designed to help you get some purchase on Tacitus and his texts.3 We will begin with some basic facts, not least to establish Tacitus as a successful ‘careerist’ within the political system of the principate who rose to the top of imperial government and stayed there even through upheavals at the centre of power and dynastic changes (1). A few comments on the configuration of power in imperial Rome follow, with a focus on how emperors stabilized and sustained their rule (2). In our survey of Tacitus’ oeuvre, brief remarks on his so-called opera minora (his ‘smaller’ – a better label would be ‘early’ – works) precede more extensive consideration of his two great works of historiography: the Histories and, in particular, the Annals. Here issues of genre – of the interrelation of content and form – will be to the fore (3). We then look at some of the more distinctive features of Tacitus’ prose style, with the aim of illustrating how he deploys language as an instrument of thought (4). The final two sections are dedicated to the two principal figures of the set text: the emperor Nero (and his propensity for murder and spectacle) (5); and the senator Thrasea Paetus, who belonged to the so-called ‘Stoic opposition’ (6). None of the sections offers anything close to an exhaustive discussion of the respective topic: all we can hope to provide are some pointers on how to think with (and against) Tacitus and the material you will encounter in the set text.

2.1 Tacitus: life and career

Cornelius Tacitus was born in the early years of Nero’s reign c. AD 56/58, most likely in Narbonese or Cisalpine Gaul (modern southern France or northwestern Italy). He died around AD 118/120.4 His father is generally assumed to have been the Roman knight whom the Elder Pliny (AD 23 – 79) identifies in his Natural History (7.76) as ‘the procurator of Belgica and the two Germanies.’ We do not know for sure that Tacitus’ first name (praenomen) was Publius, though some scholars consider it to be ‘practically certain.’5 His nomen gentile Cornelius may derive from the fact that his non-Roman paternal ancestors received citizenship in late-republican times ‘through the sponsorship of a Roman office-holder called Cornelius.’6 Our knowledge of his life and public career is also rather sketchy, but detailed enough for a basic outline. If we place the information we have or can surmise from his works on an imperial timeline, the following picture emerges:

Dates

Reigning Emperor

Tacitus

54 – 68

Nero

Born c. 56

68 – 69 (January)

Galba

69 (January – April)

Otho

69 (April – 22 December)

Vitellius

69 – 79

Vespasian

In Rome from 75 onwards (if not earlier)

77/78: marriage to Julia Agricola, daughter of Gnaeus Julius Agricola (dates: 40–93; governor of Britain 77–85)

79 – 81

Titus

80s (or even earlier): Membership in the priestly college of the Quindecimviri sacris faciundis

c. 81: Quaestor Augusti (or Caesaris)?

81 – 96

Domitian

88: Praetor

89–93: Absence from Rome, perhaps on official appointments

96 – 98

Nerva

97: Suffect consul (after the death of Verginius Rufus)

98: Publication of the Agricola and the Germania

98 – 117

Trajan

c. 101/2: Publication of the Dialogus

? c. 109–10: Publication of the Histories

112–13: Proconsulship of Asia

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!