2,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Edizioni Savine

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

AMERICA'S CUP 1851-1914 - History of the oldest trophy in international sport. From the beginning ...

Herbert Lawrence Stone

(January 18, 1871 – September 27, 1955) was a noted American publisher. Editor of Yachting (magazine) from 1908 until 1952.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

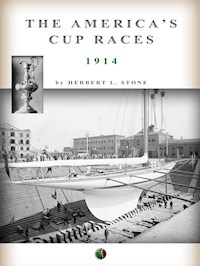

THE “AMERICA’S” CUP RACES

by Herbert L. Stone

New digital edition of:

THE “AMERICA’S” CUP RACES

by Herbert L. Stone

© 1914 by Outing Publishing Company

Copyright © 2021 - Edizioni Savine

CHAPTER I

EARLY HISTORY OF AMERICAN YACHTING — EVENTS THAT LED UP TO THE SENDING OF A YACHT TO RACE IN ENGLISH WATERS-THE BUILDING OF AMERICA.

MOORED alongside of a pier in Fort Point Channel, in the heart of Boston’s business center, with the paint flaking from her shapely sides, stained by streaks of rust from fastenings and ironwork and with her deck covered by a winter house of rough boards, unnoticed and apparently forgotten by the hurrying throng that passes her in the daily journey to and from business, lies a vessel that is at the bottom of practically all American yachting tradition and that has not only done more for the advancement of yacht designing than any other boat, but has made yachting history the world over.

Though re-built and re-rigged several times in the sixty-odd years of her existence, there is in her raking masts, graceful sheer, and clipper bow something that causes the occasional passerby who loves a boat to pause in admiration, and that is still suggestive enough of the old pilot boat model from which she was built to whisper to the initiated the word dearest to their hearts (if they happen to be yachtsmen) — America.

There she lies, after a long and, for the most part, honorable career, the same boat (at least the same soul of her if not actually the same fabric of timbers, spars, and sails) that fared forth across the Atlantic in 1851, the first of all racing yachts to cross the ocean to do battle with another nation, and the winner of a cup that now bears her name and which has stood during more than sixty years for the ultimate in a racing yacht, for the last word in speed under sail.

In order to fully appreciate what America did on her famous trip to the English yachting center, the Solent, and the subsequent bearing which the winning of an apparently insignificant cup had on the future of yachting history, one must go back to the middle of the last century and take a brief glance at the condition of yachting in this country at that time.

Previous to 1840 but very few Americans owned yachts or turned to yachting for their recreation. Most of the citizens of this country were too busy making a living and building up and developing the comparatively young republic to have sufficient means or leisure to build pleasure vessels. Along the Atlantic seaboard a number of small craft were to be found, used principally for fishing and other commercial purposes, as well as for pleasure sailing on holidays ; but neither the interest in pleasure sailing nor the number of yachts were sufficient to make an organized boat club necessary. The several clubs that were formed along the coast before this date all died a speedy and natural death after a year or so of existence.

Between 1840 and 1850 enough yachts of from twenty to fifty tons were in existence in the vicinity of New York to justify the organization of a yacht club, so that in July, 1844, a number of New York gentlemen met aboard Mr. John C. Stevens’ schooner Gimcrack in New York harbor and formed the New York

Schooner Gimcrack, aboard of which the New York Yacht Club was formed in 1844.

Yacht Club, an organization that has endured ever since, and is not only the oldest but, practically from the start, has been the foremost yacht club in this country.

Besides Mr. Stevens, the other men present at that first meeting were Hamilton Wilkes, William Edgar, John C. Jay, George L. Schuyler, Louis A. Depaw, George B. Rollins, James M. Waterbury, and James Rogers—names which should be noted well, as several of them were later identified with the building and ownership of the America.

John C. Stevens was probably the leading spirit of the little group. He was an ardent and scientific yachtsman and was elected first commodore of the new club. Eight yachts were enrolled in its fleet that first year, and the first regular meeting was held early the following spring. That next summer, also, saw the club in its own home, an unpretentious wooden building on the Weehawken flats, opposite New York, called the Elysian Fields. The first regatta was likewise held that summer, and brought out nine yachts, the smallest of 17 tons and the largest of 45, the course being from Robbins Reef, around a couple of stake boats, out through the Narrows to the South West Spit Buoy near Sandy Hook, and return, the beginning of the New York Yacht Club’s famous inside course.

But to return to Commodore (as he must now be called) John C. Stevens. He was one of four brothers, the sons of Colonel John Stevens, prominent in the Revolution and in the early history of the Republic, and an inventor of note, who owned Hoboken, where he built the family home on Castle Point, near which is now located Stevens Institute.

John C. inherited much of his father’s mechanical ability, and all of the brothers, as well as being interested in sports, were active in the development of steam navigation on the Hudson. While yet a young man John Stevens became interested in sailboats, owning a 20-footer called the Diver. This was followed by other boats of larger size, some of which he built himself and in all of which he experimented to improve the model and produce more speed. His boats were the result of careful observation, experience, and study, and he was . looked upon as an authority on yachting affairs at that period.

With his later boats, especially with his last schooner, the Gimcrack, he was associated with a man whose name is closely connected with early yacht building and modeling in this country, and to whom a great deal of credit has been given for the design of the America—one George Steers.

Though it has been said that Steers was not an American, this is not so. He was born in this country in 1820, the son of an English shipwright who came over some years before. Yachtbuilding at that time was far from the exact science it now is, and the lines of a vessel were not drawn on paper, as at present, but the craft was built largely by “ rule of thumb ” methods, following the procedure of existing vessels, with such refinements and improvements here and there as suggested themselves. Models were sometimes used, being worked out first from a block of wood and the lines shaped and faired up to give the desired form.

Young George was taught the art of modeling and laying down of vessels by his father, and as he assimilated the knowledge readily and showed great aptitude in the art of drafting as it then existed, he soon made a name for himself locally, which later spread as he turned out fast and well built vessels, sometimes as a modeler and often as foreman or as head of some shipyard where vessels were built. When only 19 years old he built for his own use a small boat which was very successful, and later turned out such well-known yachts of the period as the schooner Cygnet, the Gimcrack, Mr. Stevens’ yacht, the sloop Una (a radical departure from the then existing models), a number of fast pilot schooners, and, lastly, the U. S. frigate Niagara.

At that time the merchant marine of America was in the hey-day of its existence, with the clipper ships sailing under the Stars and Stripes sweeping the seas, and the pilot fleet of New York had to keep pace with the growing business of the port. These little schooners, that cruised from Nantucket Shoals to the Delaware Capes in the competition to put a pilot aboard of a “homeward bounder,” had to be staunch, able, and, above all, fast. Up to George Steers’ time most of them followed the existing models of bluff, round bows, full forebody, and a long, clean run—a form familiarly known as the “cod’s head and mackerel tail” model, which was used in yachts as well as in commercial vessels.

In 1849 young Steers modeled and built the pilot boat Mary Taylor, in which he discarded all previous theories of design and practically reversed the general form just mentioned, making the bow long and sharp, moving the greatest breadth farther aft, and filling out the afterbody; in other words, turning the existing model nearly end for end.

Sandy Hook Pilot Boat of the period just preceding the America.

This boat was a great success, as she outsailed all the pilot boats of the time and immediately made a name for herself and for Steers. So successful was she that other builders were soon imitating and following her model in their future vessels.

As for the reason for sending a yacht across the Atlantic in 1851 the records say that, “ it appears that there was to be a great world’s fair in England in that year, the first of the subsequent great international expositions the world has seen, and towards the fall of 1850 it was suggested by some of the promoters of the affair that it would be eminently fitting if America would send over a yacht to take part in the races to be held that year as an auxiliary feature of the exposition. As most of the larger English yachts were schooner rigged, and as the fame of the New York pilot boats had already spread abroad, it was suggested that one of these boats be sent. Englishmen were naturally anxious to try their schooners and cutters against the much-vaunted Yankee fore-and-afters, and though no mention of any definite prizes was made, it was intimated that there would be plenty to compete for, with the probability of large cash wagers and special match races.” At least, subsequent events showed that Commodore Stevens and the builders of America expected to arrange for matches with cash stakes.

That the Englishmen were hospitably inclined is shown by the following letter from the then commodore of the Royal Yacht Squadron, the Earl of Wilton, to Commodore Stevens:

7 Grosvenor Square, London.

February 22, 1851.

Sir:—Understanding from Sir H. Bulwer that a few of the members of the New York Yacht Club are building a schooner which it is their intention to bring over to England this summer, I have taken the liberty of writing to you in your capacity of Commodore to request you to convey to those members, and any friends that may accompany them on board the yacht, an invitation on the part of myself and the members of the Royal Yacht Squadron, to become visitors of the Club House at Cowes during their stay in England.

For myself I may be permitted to say that I shall have great pleasure in extending to your countrymen any civility that lies in my power, and shall be glad to avail myself of any improvements in shipbuilding that the industry and skill of your nation have enabled you to elaborate.

I remain, Sir, your obedient servant,

Wilton,

Commodore of the Royal Yacht Squadron.

The idea appealed to Commodore Stevens, of the young but vigorous New York Yacht Club, as he was a thorough sportsman, and he set about organizing a syndicate to build a suitable boat to represent this country abroad, not being satisfied to pick an existing boat, as had been suggested. This was the first syndicate boat of the New York Yacht Club, and it is interesting to note that she was the only syndicate boat built here for subsequent races for the America's cup until the Puritan, in 1885.

The members of this first syndicate were Commodore John C. Stevens, Edwin A. Stevens, his brother, George L. Schuyler, Col. James A. Hamilton, J. Beekman Finley, and Hamilton Wilkes. It was decided that the yacht was to be named America, and it was but natural that the owners should turn to George Steers, then just 30 years old, to model the new craft.

The contract for the building of the new vessel was given to William H. Brown, who had a shipyard at the foot of East 12th Street, in New York, and by whom Mr. Steers was at that time employed, probably in the capacity of foreman, or something of that sort.

Lines of the America as taken off while the yacht was docked in England.

Model of the old America, with lines as sweet and clean as any modern racer.

The contract that was made with Brown was a curious document, by which Brown stood to lose much, without any great prospect of gain. The price agreed upon for the yacht, fully equipped, was $30,000.00, and a clause in the contract called for delivery by April 1, 1851. When ready for sea she was to be tried by a member of the syndicate, Mr. Hamilton Wilkes, for twenty days, at the syndicate’s expense, and if she did not prove the fastest vessel in the United States the syndicate need not accept her. If, on the other hand, she was satisfactory, the syndicate had the option of taking her to England to race, and if she was not successful there, they could even then return her to Brown. Rather a one-sided contract it would be called in this day.

Of course the boat was not ready on contract time. Boats never are. It was May 3d before she was even launched, and on May 24th, when she was still not ready, the syndicate offered to purchase her outright for $20,000.00. It was June 18th before she was finally delivered to her owners, probably for the latter figure.

It has been said that in the design of America it is hard to say how much the work of Steers was influenced by Commodore Stevens. The younger man had the greater technical knowledge, had done a lot of experimenting with his former vessels, and was a keen observer. The Commodore, on the other hand, was a better practical yachtsman and sailor, with greater opportunity for actual experimenting with different models and for following the trend of theory and design abroad. It is probable that the best work of George Steers went into the model of the new yacht; but that Steers benefited by the experience and knowledge of the older man is, also, undoubtedly a fact.

The size decided on for the America was about 140 tons measurement. She was to be a keel boat rather than the prevailing centerboard type then so common in American yachts on account of the great amount of comparatively shallow water on our Atlantic coast, bays and sounds. In form she followed the new theory evolved by Steers in the Mary Taylor, having a sharp entrance, with concave forward sections, beam carried well aft, and a fairly easy run. Her lines, which are reproduced here, give an excellent idea of her shape, and in getting them great pains were taken to see that they were accurate. They are said to have been taken off in England at one of the yards where she was docked, without the knowledge of her owners, who refused to consider the idea of having a record of her form preserved on paper. There were, of course, no drawings of her form made when she was built. We are indebted to Mr. W. P. Stephens for the reproduction of the plans here.

The principal dimensions of the America were: Length over all, 101 feet 9 inches; length waterline, 90 feet 3 inches; beam extreme, 23 feet; forward overhang, 5 feet 6 inches; after overhang, 6 feet; draft extreme, 11 feet. Her mainmast was 81 feet long and her foremast 79 feet 6 inches, and they had an excessive rake, as was the custom then of the famous Baltimore clippers, known the world over, and also of the New York pilot schooners, while her bowsprit was thirty-two feet from tip to heel. Her main boom was 53 feet in length, and projected a long distance beyond the taffrail. Her total sail area was 5263 square feet, contained in mainsail, foresail, and single jib—a far cry from the 16,000 square feet of the last defender, Reliance—and were made by R. H. Wilson, of

Sail Plan of the America, taken from the original plan in Wilson’s sail loft at Port Jefferson.

New York, father of the present sailmaker of that name. In the voyage across they were stowed below, another suit being used for the passage. She was planked with white oak three inches in thickness, the deck being of yellow pine. She was also coppered on the bottom to just above her waterline.

It will not, perhaps, be uninteresting to see what she was like below decks, so as to form some comparison with modern yachts of her size. In general, her layout followed that of the pilot boats of the period in that there was one large main saloon extending from the mainmast aft, around the sides of which were six built-in berths with transom seats in front. A short passageway at the after end of this saloon led to a companionway to a small cockpit aft, there being a bathroom and a large clothes locker on opposite sides of this passage. Forward of the saloon were four large staterooms. Then came the galley and pantry, with a large forecastle forward containing accommodations for about fifteen men. The lazarette and sail locker were under the cockpit floor.

In her first trials in this country the new boat did not show to advantage, being beaten rather handily in several races by the Maria, a famous sloop of that day. This did not discourage her owners, however, Maria being a larger boat, in the best of condition, and with a crew aboard who had sailed her for some time. She did, however, win a number of races against other boats before leaving.

She was finally ready on June 21st, 1851, was towed down to the Hook on that day, and, casting off the towline, sail was made and she was headed to the eastward, carrying with her the hopes of her owners and of a large part of the American people. She was the “ last word ” in American shipbuilding and she was going forth, presumably, to meet the pick of England’s yachting fleet.

Aboard of her was a little company of thirteen men, including George Steers, his brother and his young nephew, Henry Steers, a youngster of 15 years; Captain “ Dick ” Brown, a Sandy Hook pilot, in command, ‘‘ Nelse ” Comstock, mate, six sailors, a steward, and cook. Commodore Stevens was to meet her on the other side.

In spite of the supposedly unlucky number aboard, they had a good and fairly fast passage

The old Maria after she was changed to schooner rig. She was the prevailing type of yacht prior to the coming of the America.

over, being 20 days to Havre, France, according to Henry Steers. Some excellent daily runs were made, the highest being 284 miles, while on six days over 200 miles were reeled off in the 24 hours. Here the yacht was to refit, and while doing so some alterations were made in her stem, these having been decided upon before leaving New York. Here also she was joined by Commodore Stevens.

CHAPTER II

ARRIVAL OF THE “AMERICA” IN ENGLAND- DIFFICULTIES OF ARRANGING A MATCH-THE RACE FOR THE ONE HUNDRED GUINEA CUP, SINCE KNOWN AS “ AMERICA’S ” CUP.

AFTER some three weeks spent in Havre refitting and getting in readiness for her invasion of the Solent, the America was ready the last of July, and, with her stores and spare gear still on board, she sailed on the 31st of that month for Cowes, Isle of Wight. That night was calm, with a thick fog, and the America was forced to anchor some six or seven miles from Cowes. When the breeze came in the following morning and blew the fog away, the English cutter Laverock, one of their crack boats, ran down from Cowes, expecting to meet the stranger, and with the intention of trying her mettle then and there. She found the American boat just weighing anchor, and hung around her persistently to force her, if possible, into a trial of speed.

Commodore Stevens might have ducked an issue then; might even have killed his boat so as not to show her true speed in order to further his cause, for he was looking to arrange future matches and it would have been to his

Cygnet, type of bluff-bowed yacht prior to 1850.

advantage not to show too much speed just then. However, seeing that he could not gracefully decline a brush, he gave the orders to “ let her go,” and with sportsmanlike instinct tackled the Laverock for all there was in his boat.

It was a beat back to Cowes, and in the few miles intervening the America worked out to windward surprisingly fast, finishing well ahead of the Englishman; and it is said that not many hours afterwards it was known throughout the yachting community that no English yacht was the America’s equal in going to windward. That little brush proved unfortunate for the American party, as subsequent events will show.

The English yachtsmen seemed impressed with America’s speed, yet the boat made an unfavorable impression by her looks, as she was radically different from the English type, and the papers spoke of her rather slightingly at first, referring to her as “a big-boned skeleton but no phantom,” and criticising her long, sharp bow and heavy raking masts, and the absence of a foretopmast, which she did not carry, following the pilot boat style.

Commodore Stevens, as the representative owner, immediately set about the business of arranging matches, but for some weeks had no success at all. The Englishmen were most hospitably inclined towards the visitors, but showed a strong disinclination to match their yachts against the American boat, and no effort was made on their part to arrange a special match or put up any suitable trophy to race for. Commodore Stevens first offered to sail a match against any of their schooners, and when this

America, with her pilot-boat rig of 1851

was not taken up he enlarged the challenge to include cutters as well.

Still meeting with no response, and thinking that if the stakes were made large enough they might prove attractive to some of the English owners, the Commodore, to quote Mr. George L. Schuyler, one of the syndicate, “ with his usual promptness, and regardless of the pockets of his associates, had posted in the clubhouse at

Cowes a challenge to sail the America a match against any British vessel whatever, for any sum from one to ten thousand guineas, merely stipulating that there should be not less than a six-knot breeze.”

Even this brought no response from the supposedly sport-loving English yachtsmen, though the offer was left open until August 17th. After it was withdrawn, Mr. Robert Stephenson came forward with an offer to match his schooner Titania against the America for a race of twenty miles to windward and return, for £100. This offer was accepted, and August 28th fixed for the date of the match, which is described in a later chapter.

This failure of British yachtsmen to take up the gauntlet flung down by their American visitors was not viewed favorably by the English people at large, and the London “ Times ” commented upon it as follows:

“ Most of us have seen the agitation which the appearance of a sparrow-hawk on the horizon creates among a flock of wood-pigeons or skylarks when, unsuspecting all danger and engaged in airy flights or playing about over the fallows, they all at once come down to the ground and are rendered almost motionless for fear of the disagreeable visitor. Although the gentlemen whose business is on the waters of the Solent are neither wood-pigeons nor skylarks, and although the America is not a sparrow-hawk, the effect produced by her apparition off West Cowes among yachtsmen seems to have been completely paralyzing. I use the word ‘ seems,’ because it cannot be imagined that some of those that took such pride in the position of England as not only being at the head of the whole race of aquatic sportsmen, but as furnishing almost the only men who sought pleasure and health upon the ocean, will allow the illustrious stranger to return with the proud boast to the New World that she had flung down the gauntlet to England, Ireland and Scotland, and that not one had been found there to take it up.”

In the meantime Commodore Stevens was notified by the officers of the Royal Yacht Squadron that there would be a regular open regatta of their club around the Isle of Wight on August 22d, for which all of their boats would be eligible, to be sailed without time allowance, and that the America would be welcomed if she desired to enter. This race was for a trophy put up by the club, valued at 100 guineas. The Americas party decided to enter the race, provided there was a good breeze, but not otherwise.

It was asking a good deal to have one yacht sail against a whole fleet, especially over a course that for a good part of the distance was not in open water, and where local knowledge of winds and tidal conditions counted for much. The same paper just quoted had this to say regarding the course:

“The course around the Isle of Wight is notoriously one of the most unfair to strangers that can be selected, and, indeed, does not appear a good race-ground to anyone, inasmuch as the current and tides render local knowledge of more value than swift sailing and nautical skill.”

Commodore Stevens and his party were greatly disappointed at this failure to arrange a match or to have the Englishmen pick out their fastest boat for a special race with the America, which they fully expected would be done when they accepted the invitation to bring a boat across to race on the Solent, and they nearly decided to send their boat home in disgust without sailing a race.

However, when the 22d came, though the wind was light, it found America at the line waiting for the starting signal. This was the fleet that the American boat was called upon to meet, all of them being British boats except America: