Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

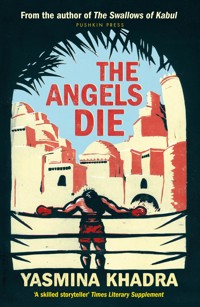

"However successful you may become, you will always be just the little Arab from the souk."Even as a child living hand-to-mouth in a ghetto, Turambo dreamt of a better future. So when his family find a decent home in the city of Oran anything seems possible. But colonial Algeria is no place to be ambitious for those of Arab-Berber ethnicity. Through a succession of menial jobs, the constants for Turambo are his rage at the injustice surrounding him, and a reliable left hook. This last opens the door to a boxing apprenticeship, which will ultimately offer Turambo a choice: to take his chance at sporting greatness or choose a simpler life beside the woman he loves.Award-winning author Yasmina Khadra gives us a stunning panorama of life in Algeria between the two world wars, in this dramatic story of one man's rise from abject poverty to a life of wealth and adulation.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 576

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE ANGELS DIE

Yasmina Khadra

Translated from the French by Howard Curtis

Copyright

First published in France as Les Anges meurent de nos blessures by Éditions Julliard Copyright © Éditions Julliard, 2013

First published in Great Britain in 2016 by Gallic Books, 59 Ebury Street, London, SW1W 0NZ

This ebook edition first published in 2016 All rights reserved © Gallic Books, 2016

The right of Yasmina Khadra to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

ISBN 9781805334316 epub

Contents

My name is Turambo and they’ll be coming to get me at dawn.

‘You won’t feel a thing,’ Chief Borselli reassures me.

How would he know anyway? His brain’s the size of a pea.

I feel like yelling at him to shut up, to forget about me for once, but I’m at the end of my tether. His nasal voice is as terrifying as the minutes eating away at what’s left of my life.

Chief Borselli is embarrassed. He can’t find the words to comfort me. His whole repertoire comes down to a few nasty set phrases that he punctuates with blows of his truncheon. I’m going to smash your face like a mirror, he likes to boast. That way, whenever you look at your own reflection, you’ll get seven years of bad luck … Pity there’s no mirror in my cell, and when you’re on death row a stay of execution isn’t calculated in years.

Tonight, Chief Borselli is forced to hold back his venom and that throws him off balance. He’s having to improvise some kind of friendly behaviour, instead of just being a brute, and it doesn’t suit him; in fact it distorts who he is. He comes across as pathetic, disappointing, as annoying as a bad cold. He’s not used to waiting hand and foot on a jailbird he’d rather be beating up so as not to lose his touch. Only two days ago, he stood me up against the wall and rammed my face into the stone – I still have the mark on my forehead. I’m going to tear your eyes out and stick them up your arse, he bellowed so that everyone could hear. That way you’ll have four balls and you’ll be able to look at me without winding me up … An idiot with a truncheon and permission to use it as he pleases. A cockerel made out of clay. Even if he rose to his full height, he wouldn’t come up to my waist, but I suppose you don’t need a stool when you’ve got a club in your hand to knock giants down to size.

Chief Borselli hasn’t been feeling well since he moved his chair to sit outside my cell. He keeps mopping himself with a little handkerchief and spouting theories that are beyond his mental powers. It’s obvious he’d rather be somewhere else: in the arms of a drunken whore, or maybe in a stadium, surrounded by a jubilant crowd screaming their heads off to keep the troubles of the world away, in fact anywhere that’s a million miles from this foul-smelling corridor, sitting opposite a poor devil who doesn’t know where to put his head until it’s time to return it to its rightful owner.

I think he feels sorry for me. After all, what is a prison guard but the man on the other side of the bars, one step away from remorse? Chief Borselli probably regrets his overly harsh treatment of me now that the scaffold is being erected in the deathly silence of the courtyard.

I don’t think I’ve hated him more than I should. The poor bastard’s only doing the lousy job he’s been given. Without his uniform, which makes him a bit more solid, he’d be eaten alive quicker than a monkey in a swamp filled with piranhas. But prison’s like a circus: on one side, there are the animals in their cages and, on the other, the tamers with their whips. The boundaries are clear, and anyone who ignores them has only himself to blame.

When I’d finished eating, I lay down on my mat. I looked at the ceiling, the walls defaced with obscene drawings, the rays of the setting sun fading on the bars, and got no answers to any of my questions. What answers? And what questions? There’s been nothing up for debate since the day the judge, in a booming voice, read out what my fate was to be. The flies, I remember, had broken off their dance in the gloomy room and all eyes turned to me, like so many shovelfuls of earth thrown on a corpse.

All I can do now is wait for the will of men to be done.

I try to recall my past, but all I can feel is my heart beating to the relentless rhythm of the passing, echoless moments that are taking me, step by step, to my executioner.

I asked for a cigarette and Chief Borselli was eager to oblige. He’d have handed me the moon on a platter. Could it be that human beings simply adjust to circumstances, with the wolf and the lamb taking it in turns to ensure balance?

I smoked until I burnt my fingers, then watched the cigarette end cast out its final demons in tiny grey curls of smoke. Just like my life. Soon, night will fall in my head, but I’m not thinking of going to sleep. I’ll hold on to every second as stubbornly as a castaway clinging to wreckage.

I keep telling myself that there’ll be a sudden turnaround and I’ll get out of here. As if that’s going to happen! The die is well and truly cast, there’s not much hope left. Hope? That’s one big swindle! There are two kinds of hope. The hope that comes from ambition and the hope that makes us expect a miracle. The first can always keep going and the second can always wait: neither of them is an end in itself, only death is that.

And Chief Borselli is still talking nonsense! What’s he hoping for? My forgiveness? I don’t hold a grudge against anyone. So, for God’s sake, shut up, Chief Borselli, and leave me to my silences. I’m just an empty shell, and my mind is a vacuum.

I pretend to take an interest in the bugs running around the cell, in the scratches on the rough floor, in anything that can get me away from my guard’s babble. But it’s no use.

When I woke up this morning, I found an albino cockroach under my shirt, the first I’d ever seen. It was as smooth and shiny as a jewel, and I told myself it was probably a good omen. In the afternoon, I heard the truck sputter into the courtyard, and Chief Borselli, who knew, gave me a furtive glance. I climbed onto my bed and hauled myself up to the skylight, but all I could see was a disused wing of the prison and two guards twiddling their thumbs. I can’t imagine a more deafening silence. Most of the time, there have been jailbirds yelling and knocking their plates against the bars, when they weren’t being beaten up by the military police. This afternoon, not a single sound disturbed my anxious thoughts. The guards have disappeared. You don’t hear their grunting or their footsteps in the corridors. It’s as though the prison has lost its soul. I’m alone, face to face with my ghost, and I find it hard to figure out which of us is flesh and which smoke.

In the courtyard, they tested the blade. Three times. Thud! … Thud! … Thud! … Each time, my heart leapt in my chest like a frightened jerboa.

My fingers linger over the purple bruise on my forehead. Chief Borselli shifts on his chair. I’m not a bad man in civilian life, he says, referring to my bump. I’m only doing my job. I mean, I’ve got kids, d’you see? He’s not telling me anything new. I don’t like to see people die, he goes on. It puts me off life. I’m going to be ill all week and for weeks to come … I wish he’d keep quiet. His words are worse than the blows from his truncheon.

I try and think of something. My mind is a blank. I’m only twenty-seven, and this month, June 1937, with the midsummer heat giving me a taste of the hell that’s waiting for me, I feel as old as a ruin. I’d like to be afraid, to shake like a leaf, to dread the minutes ticking away one by one into the abyss, in other words to prove to myself that I’m not yet ready for the gravedigger – but there’s nothing, not a flicker of emotion. My body is like wood, my breathing a diversion. I scour my memory in the hope of getting something out of it: a figure, a face, a voice to keep me company. It’s pointless. My past has shrunk away, my career has cast me adrift, my history has disowned me.

Chief Borselli is now silent.

The silence is holding the prison in suspense. I know nobody’s asleep in the cells, that the guards are close by, that my hour is stamping with impatience at the end of the corridor …

Suddenly, a door squeaks in the hushed tranquillity of the stones and muffled footsteps move along the floor.

Chief Borselli almost knocks his chair over as he stands to attention. In the anaemic light of the corridor, shadows ooze onto the floor like trails of ink.

Far, far away, as if from a confused dream, the call of the muezzin echoes.

‘Rabbi m’âak,’ cries one of the inmates.

My guts are in a tangle, like snakes writhing inside a pot. Something takes hold of me that I can’t explain. The hour has come. Nobody can escape his destiny. Destiny? Only exceptional people have one. Common mortals just have fate … The muezzin’s call sweeps over me like a gust of wind, shattering my senses in a swirl of panic. As my fear reaches its height, I dream about walking through the wall and running out into the open without turning back. To escape what? To go where? I’m trapped like a rat. Even if my legs won’t carry me, the guards will make sure they hand me over in due form to the executioner.

The clenching of my bowels threatens my underpants. My mouth fills with the stench of soil; in it, I detect a foretaste of the grave that’s getting ready to digest me until I turn to dust … It’s stupid to end up like this at the age of twenty-seven. Did I even have time to live? And what kind of life? … You’re going to make a mess of things again, and I don’t feel like cleaning up after you any more, Gino used to warn me … What’s done is done; no remorse can cushion the fall. Luck is like youth. Everybody has his share. Some grab it on the wing, others let it slip through their fingers, and others are still waiting for it when it’s long past … What did I do with mine?

I was born to flashes of lightning. On a stormy, windy night. With fists for hitting and a mouth for biting. I took my first steps surrounded by birdshit and grabbed hold of thorns to lift myself up.

Alone.

I grew up in a hellish shanty town outside Sidi Bel Abbès. In a yard where the mice were the size of puppies. Rags and hunger were my body and soul. Up before dawn at an age when I should have been carefree, I was already hard at work. Come rain or shine, I had to find a grain of corn to put in my mouth so that I could slave away again the following day without passing out. I worked without a break, often for peanuts, and by the time I got home in the evening I was dead beat. I didn’t complain. That’s just the way it was. Apart from the kids squabbling naked in the dust and the tramps you saw rotting under the bridges, their veins ravaged by cheap wine, everybody between the ages of seven and seventy-seven who could stand on their own two feet was expected to work themselves to death.

The place I worked at was a shop bang in the middle of a dangerous area, the haunt of thugs and lowlifes. It wasn’t really a shop, more like a disused, worm-eaten dugout, where Zane, who was the worst kind of crook, squatted. My job wasn’t hard: I tidied the shelves, swept the floor, delivered baskets twice my own weight, or kept a lookout whenever a widow up to her eyes in debt agreed to lift her dress at the back of the shop in return for a piece of sugar.

It was a strange time.

I saw prophets walking on water, living people who were more lifeless than corpses, riffraff sunk so low that neither demons nor the Angel of Death dared look for them there.

Even though Zane was raking it in, he never stopped complaining in order to protect himself from the evil eye, with the excuse that business was bad, that people were too broke even to have money for a rope to hang themselves with, that his creditors were shamelessly bleeding him dry, and I’d take his complaints as holy writ and feel sorry for him. Of course, to save face, he’d sometimes, either by chance or by mistake, slip a coin into my hand, but the day I was so exhausted that I asked for my back pay, he kicked me up the backside and sent me back to my mother with nothing but a promise to give me a hiding if he ever caught me hanging round the area again.

Before I reached puberty, I felt as if I’d come full circle, convinced I’d seen everything, experienced everything, endured everything.

As they say, I was immune.

I was eleven years old, and for me that was equivalent to eleven life sentences. A complete nonentity, as anonymous as a shadow, turning round and round like an endless screw. The reason I couldn’t see the light at the end of the tunnel was because there wasn’t one: I was simply travelling through an endless darkness …

Chief Borselli fiddles with the lock of my cell, removes the padlock, opens the door with an almighty creak and stands aside to let in the ‘committee’. The prison warden, my lawyer, two officials in suits and ties, a pale-faced barber with a bag at his side and the imam all advance towards me, flanked by two guards who look as if they’ve been carved out of granite.

Their formality makes my blood run cold.

Chief Borselli pushes his chair towards me and motions me to sit down. I don’t move. I can’t move. Someone says something to me. I don’t hear. All I see is lips moving. The two guards help me up and put me on the chair. In the silence, my heartbeat echoes like a mournful drum roll.

The barber slips behind me. His ratlike fingers ease my shirt collar away from my neck. My eyes focus on the shiny, freshly polished shoes around me. By now, fear has taken hold of my whole being. The end has started! It was written, except that I’m illiterate.

If I’d suspected for a single second that the curtain would come down like this, I’d never have waited for the last act: I’d have shot straight ahead like a meteorite; I’d have become one with nothingness and thrown God Himself off my trail. Unfortunately, none of these ‘if’s lead anywhere; the proof is that they always arrive too late. Every mortal man has his moment of truth, a moment designed to catch him unawares, that’s the rule. Mine took me by surprise. It seems to me like a distortion of my prayers, a non-negotiable aberration, a miscarriage of justice: whatever shape it takes, it always has the last word, and there’s no appeal.

The barber starts cutting the collar off my shirt. Every snip of his scissors cuts a void in my flesh.

In extraordinarily precise flashes, memories come back to me. I see myself as a child, wearing a hessian sack instead of a gandoura, running barefoot along dusty paths. After all, as my mother used to say, when nature, in its infinite goodness, gives us a thick layer of dirt on our feet, we can easily do without sandals. My mother wasn’t far wrong. Neither nettles nor brambles slowed down my frantic running. What exactly was I running after? … My brain echos with the rants of Chawala, a kind of turbaned madman who, winter and summer, wore a flea-ridden cloak and a gutter-cleaner’s boots. Tall, with a voluminous beard and yellow eyes painted with kohl, he liked to get up in the square, point his finger at people and predict the horrible things in store for them. I’d spend hours following him from one platform to another, so impressed I thought he was a prophet … I see Gino, my friend Gino, my dear friend Gino, his incredulous eyes wide open in the darkness of that damned stairwell as his mother’s voice rings out over the thunder: Promise me you’ll take care of him, Turambo. Promise me. I’d like to go in peace … And Nora, damn it! Nora. I thought she was mine, but nothing belonged to me. Funny how a helping hand could have changed the course of my life. I wasn’t asking for the moon, only for my share of luck, otherwise how can you believe there’s any kind of justice in this world? … The images become muddled in my head before giving in to the clicking of the scissors. In the cosmic deafness of the prison, the sound seems to suck out the air and time.

The barber puts his equipment back into his bag. He’s in a hurry to leave, only too happy not to be forced to stay for the main attraction.

The imam places a noble hand on my shoulder. I couldn’t feel more crushed if a wall had fallen on me. He asks me if there’s a particular surah I’d like to hear. With a lump in my throat, I tell him I have no preference. He chooses the Surah ar-Rahman for me. His voice penetrates into the depths of my being and, by some strange alchemy, I find the strength to stand up.

The two guards order me to follow them.

We walk out into the corridor, followed by the committee. The clanking of my chains scraping the floor turns my shivers to razor cuts. The imam continues his chanting. His gentle voice is doing me good. I’m no longer afraid to walk in the dark, the Lord is with me. ‘Mout waguef!’, an inmate says to me in a Kabyle accent. ‘Ilik dh’arguez!’, ‘Goodbye, Turambo,’ cries Bad-Luck Gégé, who’s only just out of solitary. ‘Hang on, brother. We’re coming …’ Other voices are raised, escorting me to my martyrdom. I stumble, but don’t fall. Fifty more metres, thirty … I must hang on till the end. Not just for myself but for the others. However reluctantly, I must set an example. Only the way I die can redeem a failed life. I’d like those who live on after me to talk about me with respect, to say that I left with my head held high.

My head held high?

At the bottom of a basket!

The only people who die with dignity are those who’ve fucked like rabbits, eaten like pigs, and blown all their money, Sid Roho used to say.

And what about those who are broke?

They don’t die, they just disappear.

The two guards are walking in front of me, quite impassive. The imam keeps on reciting his surah. My chains weigh a ton. The corridor hems me in on either side and I have to follow its confines.

The outside door is opened.

The cool air burns my lungs. The way the first gulp of air burns a baby’s lungs …

And there she is.

In a corner of the courtyard.

Tightly wrapped in cold and horror.

Like a praying mantis awaiting her feast.

I see her at last: Lady Guillotine. Stiff in her costume of iron and wood. With a lopsided grin. As repulsive as she’s fascinating. There she is, the porthole at the end of the world, the river of no return, the trap for souls in torment. Sophisticated and basic at one and the same time. In turn, a mistress of ceremonies and a street-corner whore. Whichever she is, she’s going to make sure you lose your head.

All at once, everything around me fades away. The prison walls disappear, the men and their shadows, the air stands still, the sky blurs. All that’s left is my heart pounding erratically and the Lady with the blade, the two of us alone, face to face, on a patch of courtyard suspended in the void.

I feel as if I’m about to faint, to fall apart and be scattered like a handful of sand in the wind. I’m grabbed by sturdy hands and put back together. I come to, fibre by fibre, shudder by shudder. There are constant flashes in my head. I see the village where I was born, ugly enough to repel both evil genies and manna from heaven, a huge enclosure haunted by beggars with glassy eyes and lips as disturbing as scars. Turambo! A godforsaken hole given over to goats and brats defecating in the open air and laughing at the strident salvoes from their emaciated rumps … I see Oran, like a splendid waterlily overhanging the sea, the lively trams, the souks and the fairs, the neon signs over the doors of nightclubs, girls as beautiful and unlikely as promises, whorehouses overrun with sailors as drunk as their boats … I see Irène on her horse, galloping across the ridges, Gino gushing blood on the staircase, two boxers beating the hell out of each other in the ring in front of a clamouring crowd, the Village Nègre and its inspired street performers, the shoeshine boys of Sidi Bel Abbès, my childhood friends Ramdane, Gomri, the Billy Goat … I see a young boy running barefoot over brambles, my mother putting her hands on her thighs in despair … Discordant voices crowd the black and white film, merging in a commotion that fills my head like scalding hail …

I’m pushed towards the guillotine.

I try and resist, but none of my muscles obey me. I walk to the guillotine as if levitating. I can’t feel the ground beneath my feet. I can’t feel anything. I think I’m already dead. A blinding white light has just seized me and flung me far, far back in time.

I

Nora

1

I owe my nickname to the shopkeeper in Graba.

The first time he saw me enter his lair, he looked me up and down, shocked by the state I was in and the way I smelt, and asked me if I came from the earth or the night. I was in bad shape, half dead from diarrhoea and exhaustion as a result of a long forced march across scrubland.

‘I’m from Turambo, sir.’

The shopkeeper smacked his lips, which were as thick as a buffalo frog’s. The name of my village meant nothing to him. ‘Turambo? Which side of hell is that on?’

‘I don’t know, sir. I need half a douro’s worth of yeast and I’m in a hurry.’

The shopkeeper turned to his half-empty shelves and, holding his chin between his thumb and index finger, repeated, ‘Turambo? Turambo? Never heard of it.’

From that day on, whenever I passed his shop, he’d cry out, ‘Hey, Turambo! Which side of hell is your village on?’ His voice carried such a long way that gradually everyone started calling me Turambo.

My village had been wiped off the map by a landslide a week earlier. It was like the end of the world. Wild lightning flashes streaked the darkness, and the thunder seemed to be trying to smash the mountains to pieces. You couldn’t tell men from animals any more; they were all tearing in every direction, screaming like creatures possessed. In a few hours, the torrents of rain had swept away our hovels, our goats and donkeys, our cries and prayers, and all our landmarks.

By morning, apart from the survivors shivering on the mud-covered rocks, nothing remained of the village. My father had vanished into thin air. We managed to dredge up a few bodies, but there was no trace of the broken face that had survived the deluge of fire and steel in the Great War. We followed the ravages of the flood as far as the plain, searched bushes and ravines, lifted the trunks of uprooted trees, but all in vain.

An old man prayed that the victims might be at rest, my mother shed a tear in memory of her husband, and that was it.

We considered putting everything back that had been scattered by the storm, but we didn’t have the means, or the strength to believe it was possible. Our animals were dead, our meagre crops were ruined, our zinc shelters and our zaribas were beyond repair. Where the village had been, there was nothing but a mudslide on the side of the mountain, like a huge stream of vomit.

After assessing the damage, my mother said to us, ‘Mortal man has only one fixed abode: the grave. As long as he lives, there’s nothing he can take for granted, neither home nor country.’

We bundled up the few things the disaster had deigned to leave us and set off for Graba, a ghetto area of Sidi Bel Abbès where wretches thrown off their lands by typhus or the greed of the powerful arrived by the score.

With my father gone, my young uncle Mekki, who wasn’t very far into his teens, declared himself the head of the family. He had a legitimate claim, being the eldest male.

There were five of us in a shack wedged between a military dumping ground and a scraggy orchard. There was my mother, a sturdy Berber with a tattooed forehead, not very beautiful but solid; my aunt Rokaya, whose pedlar husband had walked out on her over a decade earlier; her daughter Nora, who was more or less the same age as me; my fifteen-year-old uncle Mekki, and me, four years his junior.

Since we didn’t know anyone, we had only ourselves to rely on.

I missed my father.

Strangely, I don’t remember ever seeing him up close. Ever since he’d come back from the war, his face shattered by a piece of shrapnel, he’d kept his distance, sitting all day long in the shade of a solitary tree. When my cousin Nora took him his meals, she’d approach him on tiptoe, as if she was feeding a wild animal. I waited for him to return to earth, but he refused to come down from his cloud of depression. After a while, I ended up confusing him with someone I may once have seen and eventually ignored him completely. His disappearance merely confirmed his absence.

And yet in Graba, I couldn’t help thinking about him every day.

Mekki promised we wouldn’t stay long in this shanty town if we worked hard and made enough money to rebuild our lives somewhere else. My mother and my aunt decided to start making biscuits, which my uncle would sell to cheap restaurants. I wanted to lend a hand – kids a lot weaker than me were working as porters, donkey drivers and soup vendors, and doing well – but my uncle refused to hire me. I was bright, he had to admit that, I just wasn’t bright enough to handle rascals capable of beating the devil himself at his own game. He was particularly afraid I’d be skinned alive by the first little runt I came across.

And so I was left to my own devices.

In Turambo, my mother had told me about dubious shanty towns inhabited by creatures so monstrous I had bad dreams about them, but I’d never imagined I’d end up in one of them one day. And now here I was, slap bang in the middle of one, but this was no bedtime story. Graba was like an open-air asylum. It was as if a tidal wave had swept across the hinterland and tons of human flotsam and jetsam had somehow been tossed here. Labourers and beasts of burden jostled each other in the same narrow alleys. The rumbling of carts and the barking of dogs created a din that made your head spin. The place swarmed with crippled veterans and unemployed ex-convicts, and as for beggars, they could moan until their voices gave out, they’d never get a grain of corn to put in their mouths. The only thing people had to share was bad luck.

Everywhere amid the rickety shacks, where every alley was an ordeal to walk down, snotty-nosed kids engaged in fierce organised battles. Even though they barely came up to your knee, they already had to fend for themselves, and the future they could look forward to was no brighter than their early years. The birthright automatically went to the one who hit hardest, and devotion to your parents meant nothing once you’d given your allegiance to a gang leader.

I wasn’t scared of these street urchins; I was scared of becoming like them. In Turambo, nobody swore, nobody looked their elders directly in the face; people showed respect, and if ever a kid got a bit carried away, you just had to clear your throat and he’d behave himself. But in this hellhole that stank of piss, every laugh, every greeting, every sentence came wrapped in obscenity.

It was in Graba that I first heard adults speak crudely.

The shopkeeper was getting some air outside his shack, his belly hanging down over his knees. A carter said, ‘So, fatty, when’s the baby due?’

‘God knows.’

‘Boy or girl?’

‘A baby elephant,’ said the shopkeeper, putting his hand on his flies. ‘Want me to show you its trunk?’

I was shocked.

You couldn’t hear yourself breathe until the sun went down. Then the ghetto would wrap itself around its troubles and, soothed by the echoes of its foul acts, allow itself to fade into the darkness.

In Graba, night didn’t come, didn’t fall, but, rather, poured down as though from a huge cauldron of fresh tar; it cascaded from the sky, thick and elastic, engulfing hills and forests, pushing its blackness deep into our minds. For a few moments, like hikers caught unawares by an avalanche, people would fall abruptly silent. Not a sound, not a rustle in the bushes. Then, little by little, you would hear the crack of a strap, the clatter of a gate, the cry of a baby, kids squabbling. Life would slowly resume and, like termites nibbling at the shadows, the anxieties of the night would come to the surface. And just as you blew out the candle to go to sleep, you’d hear drunks yelling and screaming in the most terrifying way; anyone lingering on the streets had to hurry home if they didn’t want their bodies to be found lying in pools of blood early the following morning.

‘When are we going back to Turambo?’ I kept asking Mekki.

‘When the sea gives back to the land what it took away,’ he would answer with a sigh.

We had a neighbour in the shack opposite ours, a young widow of about thirty who would have been beautiful if only she’d taken a little care of herself. Always in an old dress, her hair in a mess, she’d sometimes buy bread from us on credit. She’d rush in, mutter an excuse, snatch her order from my mother’s hands and go back home as quickly as she’d come.

We thought she was strange; my aunt was sure the poor woman was possessed by a jinn.

This widow had a little boy who was also strange. In the morning, she’d take him outside and order him to sit at the foot of the wall and not move for any reason. The boy was obedient. He could stay in that blazing heat for hours, sweating and blinking his eyes, salivating over a crust of bread, with a vague smile on his face. Seeing him sitting in the same spot, nibbling at his mouldy piece of bread, made me so uneasy that I’d recite a verse to ward off the evil spirits that seemed to keep him company. Then, unexpectedly, he started following me from a distance. Whether I went to the scrub or the military dumping ground, every time I turned round I saw him right behind me, a walking scarecrow, his crust in his mouth. I’d try to chase him away, threatening him, even throwing stones at him, but he’d just retreat for a few moments then, at a bend in the path, reappear behind me, always keeping at a safe distance.

I went to see his mother and asked her to keep her kid tied up because I was tired of him always following me. She listened without interrupting, then told me he had lost his father and so he needed company. I told her I already found it hard to bear my own shadow. ‘It’s your choice,’ she sighed. I expected her to lose her temper like the other women in the neighbourhood whenever they disagreed with something, but she just went back to her chores as though nothing had happened. Her resignation made me feel sorry for her. I took the boy under my wing. He was older than me, but judging by the naive grin on his face, his brain must have been smaller than a pinhead. And he never spoke. I’d take him to the woods to pick jujubes or up the hill to look down at the railway tracks glittering among the stones. In the distance, you could see goatherds surrounded by their emaciated flocks and hear the little bells teasing the lethargic silence. Below the hill, there was a gypsy encampment, recognisable by its dilapidated caravans.

At night, the gypsies would light fires and pluck their guitars until dawn. Even though they mostly twiddled their thumbs the lids of their cooking pots were constantly clattering. I think their God must have been quite a good one. True, he didn’t exactly shower them with his benevolence, but at least he made sure they always had enough to eat.

We met Pedro the gypsy in the scrub. He was pretty much the same age as us and knew all the burrows where game went to hide. Once his basket was filled, he’d take out a sandwich and share it with us. We became friends. One day, he invited us to the camp. That’s how I learnt to take a close look at these tricksters whose food fell from the skies.

In spite of a quick temper, Pedro’s mother was basically good-natured. She was a fat redhead with a moustache, a lively temperament, and breasts so large you couldn’t tell where they stopped. She never wore anything under her dress, so when she sat on the ground you could see her pubic hair. Her husband was a broken-down septuagenarian who used an ear trumpet to hear and spent his time sucking at a pipe as old as the hills. He’d laugh whenever you looked at him, and open his mouth to reveal a single rotten tooth that made his gums look all the more repulsive. And yet in the evening, when the sun went down behind the mountains, the old man would wedge his violin under his chin and draw from the strings of his instrument laments that were the colour of the sunset and filled us with sweet melancholy. I’d never again hear anyone play the violin better than he did.

Pedro had lots of talents. He could wrap his feet round the back of his neck and stand on his hands, he could juggle with torches; his great ambition was to join a circus. He’d describe it to me: a big tent with corridors and a ring where people went to cheer wild animals that could do amazing things and acrobats who performed dangerous stunts ten metres above the ground. Pedro would gush, telling me how they would also exhibit human monsters, dwarfs, animals with two heads and women with bodies you could only dream about. ‘They’re like us,’ he’d say. ‘They’re always travelling, except that they have bears, lions and boa constrictors with them.’

I thought he was making it all up. I found it hard to picture a bear riding a bicycle, or men with painted faces and shoes half a metre long. But Pedro was good at presenting things, and even when the world he raved about was far beyond my understanding, I happily went along with his crazy stories. Besides, everybody in the camp let their imagination run riot. You’d think you were at an academy for the greatest storytellers on earth. There was old Gonsho, a little man with tattoos from his thighs up to his neck, who claimed he’d been killed in an ambush. ‘I was dead for a week,’ he’d say. ‘No angel came to play me a lullaby on his harp, and no demon stuck his pitchfork up my arse. All I did was drift from sky to sky. Believe it or not, I didn’t see any Garden of Eden or any Gehenna.’

‘That makes sense,’ said Pepe, the elder of the group, who was as ancient as a museum piece. ‘First, everybody in the world would have to be dead. Then there’ll be the Last Judgement, and only then will some be moved to heaven and others to hell.’

‘You’re not going to tell me that people who kicked the bucket thousands of years ago are going to have to wait for there to be nobody left on earth before they’re judged by the Lord?’

‘I’ve explained it to you before, Gonsho,’ Pepe replied condescendingly. ‘Forty days after they die, people become eligible for reincarnation. The Lord can’t judge us on one life alone. So he brings us back wealthy, then poor, then as kings, then as tramps, as believers, as brigands, and so on, to see how we behave. He isn’t going to create someone who’s in the shit and then condemn him without giving him a chance to redeem himself. In order to be fair, he makes us wear all kinds of hats, then he takes an overall look at all our different lives, so that he can decide on our fate.’

‘If what you say is true, why is it I’ve come back with the same face and in the same body?’

And Pepe, like an infinitely patient teacher, replied, ‘You were dead for only a week. It takes forty days to pass on. And besides, gypsies are the only ones who have the privilege to be reborn as gypsies. Because we have a mission. We’re constantly travelling in order to explore the paths of destiny. We’ve been given the task of seeking the Truth. That’s why since the dawn of time, we’ve never stayed in one place.’

Making a circular movement with his finger at his temple, Pepe encouraged Gonsho to think for a few moments about what he’d just told him.

The debate could have gone on indefinitely without either of them agreeing with the other. For gypsies, arguing wasn’t about what you believed, it was about being stubborn. When you had an opinion, you held on to it at all costs because the worst way to lose face was to abandon your point of view.

Gypsies were colourful, fascinating, crazy characters, and they all had a religious sense of responsibility towards their families. They could disagree, yell at one another, and even come to blows, but they all deferred to the Mama, who kept an eye on everything.

Ah, the Mama! She’d given me her blessing the moment she’d seen me. She was a kind of impoverished dowager, lounging on her embroidered cushions at the far end of her caravan, which was piled high with gifts and relics; the tribe worshipped her like a sacred cow. I’d have liked to throw myself into her arms and sink into her flesh.

I felt comfortable among the gypsies. My days were filled with fun and surprises. They gave me food and let me enjoy myself as I wished … Then, one morning, the caravans were gone. All that was left of the camp was a few traces of their stay: rutted tracks, a few shoes with holes in them, a shawl hanging from a bush, dog mess. Never had a place seemed to me as ruined as this patch abandoned by the gypsies and returned to its bleak former state. For weeks I went back, conjuring up memories in the hope of hearing an echo, a laugh, a voice, but there was no answer, not even the sound of a violin to act as an excuse for my sorrow. With the gypsies gone, I was back to a grim future, to dull, endless days that went round in circles like a wild animal in a cage.

The days passed but didn’t advance, monotonous, blind, empty; it was as if they were walking over my body.

At home, I was an extra burden. ‘Go back to the street; may the earth swallow you. Can’t you see we’re working?’

I was scared of the street.

You couldn’t go to the military dumping ground any more since the numbers of scavengers had increased, and woe betide anyone who dared fight them over a piece of rubbish.

I fell back on the railway and spent my time watching out for the train and picturing myself on it. I ended up jumping on. The local train had broken down and was stuck on the rails, like a huge caterpillar about to give up the ghost. Two mechanics were fussing around the locomotive. I approached the last carriage. The door was open. I hoisted myself on board with my partner in misfortune, sat down on an empty sack, and gazed up at the sky through the slits in the roof. I imagined myself travelling across green countryside, bridges and farms, fleeing the ghetto where nothing good ever happened. Suddenly, the carriage started moving. The boy staggered and clung to the wall. The locomotive whistle made me leap to my feet. Outside, the countryside began slowly rolling by. I jumped off first, almost breaking my ankle on the ballast. But the boy wouldn’t let go of the wall. Jump off, I’ll catch you, I shouted. He was paralysed and wouldn’t jump. The more the train gathered speed, the more I panicked. Jump, jump … I started running, the ballast cutting into my feet like broken bottles. The boy was crying. His moaning rose above the din of the livestock carriages. I realised he wasn’t going to jump. It was up to me to get him. As usual. I ran and ran, my chest burning, my feet bleeding. I was two fingers away from gaining a handhold, three fingers, four, ten, thirty … It wasn’t because I was slowing down; the iron monster was growing bolder as the locomotive increased its output of smoke. At the end of a frantic run, I stopped, my legs cut to pieces. All I could do was watch the train get further away until it vanished in the dust.

I followed the track for many miles, limping under a blazing sun … I caught sight of a figure and rushed towards it, thinking it was the boy. It wasn’t him.

The sun was starting to go down. I was already a long way from Graba. I had to get home before nightfall, or I might get lost too.

The widow was at our house, pale with worry. When she saw me on my own, she rushed out into the street and turned even paler than before.

‘What have you done with my baby?’ She shook me angrily. ‘Where’s my child? He was with you. You were supposed to look after him.’

‘The train —’

‘What train?’

I felt a tightness in my throat. I couldn’t swallow.

‘What about the train? Say something!’

‘It took him away.’

Silence.

The widow didn’t seem to understand. She furrowed her brow. I felt her fingers go limp on my shoulders. Against all expectations, she gave a little laugh and turned pensive. I thought she’d bounce back, sink her claws into me, break up our shack and us with it, but she leant against the wall and slid down to the ground. She stayed like that, with her elbows on her knees and her head in her hands, a dark look in her eyes. A tear ran down her cheek; she didn’t wipe it away. ‘Whatever God decides, we must accept,’ she sighed in a muted voice. ‘Everything that happens in this world happens according to His will.’

My mother tried to put a sympathetic hand on her shoulder. She shook it off with a gesture of disgust. ‘Don’t touch me. I don’t want your pity. Pity never fed anyone. I don’t need anybody any more. Now that my son’s gone, I can go too. I’ve been wanting to put an end to this lousy life for years. But my son wasn’t right in the head. I couldn’t see him surviving among people who are worse than wolves … I can’t wait to have a word with the One who created me just to make me suffer.’

‘Are you mad? What are you talking about? It’s a sin to kill yourself.’

‘I don’t think there could possibly be a hell worse than mine, either in the sky or anywhere else.’

She looked up at me and it was as if the distress of the whole of humanity was concentrated in her eyes.

‘Torn to pieces by a train! My God! How can I do away with a child like that after putting him through so much?’

I was speechless, upset by her ranting.

She pressed down on the palms of her hands and got unsteadily to her feet. ‘Show me where my baby is. Is there anything left of him for me to bury?’

‘He isn’t dead!’ I cried.

She shuddered. Her eyes struck me with the ferocity of lightning. ‘What? Did you leave my son bleeding on the railway tracks?’

‘He wasn’t run over by the train. We got on it, and when the train started, I jumped off and he stayed on. I shouted to him to jump but he didn’t dare. I ran after the train and walked along the rails, but he didn’t get off anywhere.’

The widow put her head in her hands. Once again, she didn’t seem to understand. Suddenly, she stiffened. I saw her facial expression go from confusion to relief, then from relief to panic, and then from panic to hysteria. ‘Oh, God! My son is lost! They’ll eat him alive. He doesn’t even know how to hold out his hand. Oh, my God! Where’s my baby?’

She took me by the throat and started to shake me, almost dislocating my neck. My mother and aunt tried to get me away from her; she pushed them back with a kick and, totally losing her mind, started screaming and spinning like a tornado, knocking down everything in her path. Suddenly, she howled and collapsed, her eyes rolled back, her body convulsed.

My mother got up. She had scratches all over. With amazing calm, she fetched a large jailer’s key and slipped it into the widow’s fist – a common practice with people who fainted from dizziness or shock.

Dumbfounded, my aunt ordered her daughter to go and fetch Mekki before the madwoman returned to her senses.

Mekki didn’t beat about the bush. Nora had told him everything. He was all fired up and didn’t want to hear any more. In our family, you hit first, and then you talked. You bastard, I’m going to kill you. He rushed at me and started beating me up. I thought he’d never stop.

My mother didn’t intervene.

It was men’s business.

Having beaten me thoroughly, my uncle ordered me to take him to the railway track and show him the direction the train had gone in. I could barely stand. The ballast had injured my feet, and the beating had finished me off.

‘How am I supposed to look for him in the dark?’ Mekki cursed, leaving the shack.

At dawn, Mekki wasn’t back. The widow came to ask for news every five minutes, in a state of mental collapse.

Three days passed and still there was nothing on the horizon. After a week, we began to fear the worst. My aunt was constantly on her knees, praying. My mother kept going round in circles in the one room that made up our house. ‘I suppose you’re proud of yourself,’ she grunted, resisting the impulse to hit me. ‘You see where your mischief has landed us? It’s all your fault. For all we know, the jackals have long since chewed your uncle’s bones. What will become of us without him?’

Just when we were beginning to lose hope, we heard the widow cry out. It was about four in the afternoon. We ran out of the shack. Mekki could barely stand up, his face was dark, and he was covered in dirt. The widow was hugging her child tightly to her, pulling up his gaiters to see if he was hurt, feeling his scalp for any bumps or injuries; the boy showed the effects of wandering and hunger, but was safe and sound. He was staring at me dull-eyed, and pointing his finger at me the way you point at a culprit.

2

Ogres are nothing but hallucinations born of our superstitions, and an excuse for them, which is why we are no better than they are, because, as both false witnesses and stern judges, we often condemn before deliberating.

The ogre known as Graba wasn’t as monstrous as all that.

From the hill that served as my vantage point, I had seen its people as plague victims and its slums as deadly traps. I was wrong. Seen from close up, the ghetto was simply living as best it could. It might have seemed like purgatory, but it wasn’t. In Graba, people weren’t paying for their crimes or their sins, they were just poor, that was all.

Driven by boredom and idleness, I started venturing further and further into the ghetto. I was just beginning to feel part of it when I had my baptism of fire. Which of course I’d been expecting.

A carter offered me a douro to help him load about a hundred bundles of wood onto his cart. Once the job was done, he paid me half the promised sum, swearing on his children’s heads that it was all he had on him. He seemed sincere. I was watching him walk away when a voice behind me cried out, ‘Are you trying to muscle in on my territory?’

It was the Daho brothers. They were barring my way.

I sensed things were about to go downhill. Peerless street fighters, they reigned supreme over the local kids. Whenever a boy came running through the crowd, his face reduced to a pulp, it meant the Dahos weren’t far away. They were only twelve or thirteen, but talked through the sides of their mouths like old lags. Behind them, their bodyguards rubbed their hands at the prospect of a thrashing. The Daho brothers couldn’t just go on their way. Wherever they stopped, blood had to flow. It was the rule. Kings hate truces, and the twins didn’t believe in taking a well-earned rest. Squat and faun-like, their faces so identical you felt you were seeing the same disaster twice, they were as fast as whips and just as sharp. Adults nicknamed them Gog and Magog, two irredeemable little pests bound to end up on the scaffold as surely as ageing virgins were destined to marry their halfwit cousins. There was no getting away from them and I was angry with myself for having crossed their path.

‘I don’t want to fight,’ I said.

This spontaneous surrender was greeted with sardonic laughter.

‘Hand over what you’ve got in your pocket.’

I took out the coin the carter had given me and held it out. My hand was steady. I wasn’t looking for trouble. I wanted to get home in one piece.

‘You have to be nuts to be content with this,’ Daho One said, weighing my earnings contemptuously in his hand. ‘You don’t move a cartload of stuff for half a douro, you little toerag. Any idiot would have asked for three times this much.’

‘I didn’t know,’ I said apologetically.

‘Turn out your pockets, now.’

‘I’ve already given you everything I have.’

‘Liar.’

I could see in their eyes that confiscating my pay was just the start and that what mattered was the thrashing. I immediately went on the defensive, determined to give as good as I got. The Daho brothers always hit first, without warning, hoping to take their victim by surprise. They would strike simultaneously, in a perfectly synchronised movement, with a headbutt to the nose and a kick between the legs to disconcert their prey. The rest was just a formality.

‘Aren’t you ashamed of yourselves?’ a providential voice rang out. ‘A whole bunch of you picking on a little kid?’

The voice belonged to a shopkeeper standing in the doorway of his establishment with his hands on his hips. His tarboosh was tilted at a rakish angle over one eye and his moustache was turned up at the ends. He moved his fat carcass to adjust his Turkish sirwal and, advancing into the sunlight, looked around at the gang before letting his keen eyes fall on the twins.

‘If you want to take him on, do it one at a time.’

I’d been expecting the shopkeeper to come to my rescue, but all he was doing was organising my beating in a more conventional way, which wasn’t exactly a lucky break for me.

Daho One accepted the challenge. Sneering, his eyes shining with wicked glee, he rolled up his sleeves.

‘Move back,’ the shopkeeper ordered the rest of the gang, ‘and don’t even think of joining in.’

A wave of anticipation went through the gang as they formed a circle around us. Daho One’s snarl increased as he looked me up and down. He feinted to the left and tried to punch me but only brushed my temple. He didn’t get a second chance because my fist shot out in retaliation and, much to my surprise, hit its target. The scourge of the local kids flopped like a puppet and collapsed in the dust, his arms outstretched. The gang gasped in outraged amazement. The other twin stood there stunned for a few moments, unable to understand or admit what his eyes were telling him, then, in a rage, he ordered his brother to get up. But his brother didn’t get up. He was sleeping the sleep of the just.

Sensing the turn things seemed to be taking, the shopkeeper came and stood beside me and we both looked at the gang picking up their martyr, who was deep in an impenetrable dream filled with bells and birdsong.

‘You didn’t play fair,’ cried a frizzy-haired little runt with legs like a wading bird. ‘You tricked him. You’ll pay for that.’

‘We’ll be back for you,’ Daho Two vowed, wiping his snotty nose with the back of his hand.

The shopkeeper was a little disappointed by my rapid victory. He had been hoping for a more substantial show, full of falls and suspense and dodges and devastating punches, thus getting a decent slice of entertainment for free. Reluctantly he admitted to me that, all things considered, he was delighted that someone had succeeded in soundly thrashing that lowlife, who blighted the ghetto and thought he could get away with anything because there was nobody to take him on.

‘You’re really quick,’ he said, flatteringly. ‘Where did you learn to hit like that?’

‘That’s the first time I was ever in a fight, sir.’

‘Wow, such promise! How would you like to work for me? It isn’t difficult. All you have to do is keep guard when I’m not there and handle a few little things.’

I took the bait without even asking about my wages, only too happy to be able to earn my crust and make a contribution to the family’s war chest.

‘When do I start, sir?’

‘Right away,’ he said, pointing reverently at his dilapidated shop.

I had no way of knowing that when charitable people intervene to save your skin, they don’t necessarily plan to leave any of it on your back.

The shopkeeper was called Zane, and it was he who taught me that the devil had a name.

What Zane referred to as little things were more like the labours of Hercules. No sooner had I finished one task than I was given another. I wasn’t allowed a lunch break or even a moment to catch my breath. I was told to tidy the shambles that was the premises (a veritable Ali Baba’s cave), stack the shelves, polish the bric-a-brac, dislodge the spiders, a bucket of water in one hand and a ceiling brush in the other, and deal with deliveries. Before giving me a trial, Zane subjected me to ‘loyalty’ tests, leaving money and other bait lying around to see how honest I was; I didn’t touch a thing.