12,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

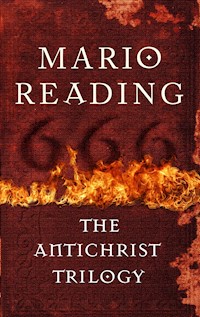

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

From the No. 1 bestselling author of Nostradamus: The Complete Prophecies for the Future The Antichrist Trilogy, now collected in one thrilling e-book... The Nostradamus Prophecies Adam Sabir is a writer desperate to revive his flagging career; Achor Bale is a member of an ancient secret society that has dedicated itself to the protection and support of the 'Three Antichrists' foretold in Nostradamus's verses - Napoleon, Adolf Hitler, and the 'one still to come'... The pair embark on a terrifying chase through the ancient Romany encampments of France in a quest to locate the missing verses. The Mayan Codex Adam Sabir has discovered the missing quatrains of Nostradamus, and the events they foretell are coming true. But there's one prophecy he can't fully decipher, and it warns of the imminent arrival of the Third Antichrist. As Sabir puzzles over the riddle, a descendant of the Mayans begins a dangerous journey to deliver a sacred codex which will reveal the secret of Nostradamus' prophecy... The Third Antichrist Scholar Adam Sabir has decoded the identity of the Third Antichrist. He alone knows the one who can prevent this tyrant's rise. The fate of the world is in his hands...The countdown to Armageddon has begun.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

Mario Reading’s varied life has included selling rare books, teaching riding in Africa, studying dressage in Vienna, running a polo stable in Gloucestershire and maintaining a coffee plantation in Mexico. An acknowledged expert on the prophecies of Nostradamus, Reading is the author of eight nonfiction titles, as well as the bestselling novel The Nostradamus Prophecies.

First published in Great Britain 2012 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

The Antichrist Trilogy © Atlantic Books Ltd 2013

The Nostradamus Prophecies © Mario Reading 2009The Mayan Codex © Mario Reading 2010The Third Antichrist © Mario Reading 2011

The moral right of Mario Reading to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

The novels in this anthology are entirely works of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

E-book ISBN: 978 0 85789 684 1

Corvus An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd Ormond House 26–27 Boswell Street London WC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

Contents

The Nostradamus Prophecies

The Mayan Codex

The Third Antichrist

Contents

Cover

AUTHOR’S NOTE

EPIGRAPH

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

PROLOGUE

PART ONE

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

Chapter 57

Chapter 58

Chapter 59

Chapter 60

Chapter 61

Chapter 62

Chapter 63

Chapter 64

Chapter 65

Chapter 66

Chapter 67

Chapter 68

PART TWO

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

Chapter 57

Chapter 58

Chapter 59

Chapter 60

Chapter 61

Chapter 62

Chapter 63

Chapter 64

Chapter 65

Chapter 66

Chapter 67

Chapter 68

Chapter 69

Chapter 70

Chapter 71

Chapter 72

Chapter 73

Chapter 74

Chapter 75

Chapter 76

Chapter 77

Chapter 78

Chapter 79

Chapter 80

Chapter 81

Chapter 82

Chapter 83

Chapter 84

Chapter 85

Chapter 86

Chapter 87

POSTSCRIPT

For my son, Lawrence, con todo mi cariño

AUTHOR’S NOTE

Nostradamus did indeed only complete 942 quatrains out of 1000, representing his intended total of ten centuries of 100 quatrains apiece. The remaining fifty-eight quatrains are missing, and, to this day, they have never been found.

The Will that I have used in the book is Nostradamus’s original last Will and Testament (in the original French, with my translation appended). I concentrate particularly on the codicil to the Will in which Nostradamus bequeaths two secret coffers to his eldest daughter, Madeleine, with the stipulation that ‘no one but her may look at or see those things which he has placed inside the coffers’. All this is on public record.

The gypsy lore, language, customs, names, habits and myths depicted in the book are all accurate. I have merely concatenated the customs of a number of different tribes into one, for reasons of fictional convenience.

No definite proof of the existence of the Corpus Maleficus has been found to date. Which doesn’t mean it isn’t out there.

Mario Reading, 2009

EPIGRAPH

‘As it had never occurred to him to leave word behind, he was mourned over for dead till, after eight months, his first letter arrived from Talcahuano.’

From Typhoon by Joseph Conrad

‘Our business in this world is not to succeed, but to continue to fail, in good spirits.’

Robert Louis Stevenson, Complete Works, vol. 26,Reflections and Remarks on Human Life, s.4

‘Perhaps proof of how aleatory the concept of nationality is lies in the fact that we must learn it before we can recognize it as such.’

From A Reading Diary by Alberto Manguel

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Writing and researching a book such as this can be a dauntingly solitary experience, so one is all the more grateful when anybody outside one’s own immediate family takes an interest in it. My agent, Oli Munson of Blake Friedmann, has championed the book from the very outset – from larval caterpillar, through pupal, to fully-fledged butterfly. I am profoundly indebted to him both for his friendship and for his steadfast support, and indeed to everyone at Blake Friedmann for their collective and multifaceted accomplishments. Ravi Mirchandani, my editor at Atlantic, also saw early virtue in the book, as did my German editor, Urban Hofstetter at Blanvalet, who was the first major international publisher to get 100 per cent behind it – I am deeply grateful to them both. Thank you, too, to the semi-invisible sales force at Atlantic, particularly in the form of managing director Daniel Scott, whose personal memo praising the book raised my spirits quite remarkably. Also to the nameless bouquiniste on the Left Bank of the Seine who spent nearly the whole of a summer afternoon generously sharing with me his insights into the Manouche gypsies. Finally I would like to thank the British Library and the Bibliothèque Nationale de France for their simple existence. Authors everywhere are in their debt.

PROLOGUE

La Place de l’Etape, Orléans. 16 June 1566

De Bale nodded and the bourreau began to haul away at the pulley mechanism. The Chevalier de la Roche Allié was in full armour, so the apparatus strained and groaned before the ratchet took and the Chevalier began to rise from the ground. The bourreau had warned de Bale about the strain and its possible consequences, but the Count would hear none of it.

‘I have known this man since childhood, Maître. His family is amongst the most ancient in France. If he wants to die in his armour, such is his right.’

The bourreau knew better than to argue – men who argued with de Bale usually ended up on the rack, or scalded with boiling spirits. De Bale had the ear of the King and the seal of the Church. In other words the bastard was untouchable. As close to terrestrial perfection as it was possible for mortal man to be.

De Bale glanced upwards. Because of the lèse-majesté nature of his crimes, de la Roche Allié had been sentenced to a fifty-foot suspension. De Bale wondered if the man’s neck ligaments would withstand the strain of both the rope and the 100 pounds of plate steel his squires had strapped him into before the execution. It would not be well viewed if the man broke in two before the drawing and the quartering. Could de la Roche Allié have thought of this eventuality when he made his request? Planned the whole thing? De Bale thought not. The man was an innocent – one of the old breed.

‘He’s reached the fifty, Sir.’

‘Let him down.’

De Bale watched the sack of armour descending towards him. The man was dead. It was obvious. Most of his victims struggled and kicked at this point in the proceedings. They knew what was coming.

‘The Chevalier is dead, Sir. What do you want me to do?’

‘Keep your voice down, for a start.’ De Bale glanced over at the crowd. These people wanted blood. Huguenot blood. If they didn’t get it, they would turn on him and the executioner and tear them limb from limb. ‘Draw him anyway.’

‘I’m sorry, Sir?’

‘You heard me. Draw him anyway. And contrive that he twitches, man. Shriek through your nose if you have to. Ventriloquise. Make a big play with the entrails. The crowd have to think that they see him suffer.’

The two young squires were moving forward to unbuckle the Chevalier’s armour.

De Bale waved them back. ‘The Maître will do it. Return to your homes. Both of you. You have done your duty by your master. He is ours now.’

The squires backed away, white-faced.

‘Just take off the gorget, plackart and breastplate, Maître. Leave the greaves, cuisses, helm and gauntlets in place. The horses will do the rest.’

The executioner busied himself about his business. ‘We’re ready, Sir.’

De Bale nodded and the bourreau made his first incision.

Michel de Nostredame’s House, Salon-de-Provence, 17 June 1566

‘De Bale is coming, Master.’

‘I know.’

‘How could you know? It is not possible. The news was only brought in by carrier pigeon ten minutes ago.’

The old man shrugged, and eased his oedema-ravaged leg until it lay more comfortably on the footstool. ‘Where is he now?’

‘He is in Orléans. In three weeks he will be here.’

‘Only three weeks?’

The manservant moved closer. He began to wring his hands. ‘What shall you do, Master? The Corpus Maleficus are questioning all those whose family were once of the Jewish faith. Marranos. Conversos. Also gypsies. Moors. Huguenots. Anyone not by birth a Catholic. Even the Queen cannot protect you down here.’

The old man waved a disparaging hand. ‘It hardly matters any more. I shall be dead before the monster arrives.’

‘No, Master. Surely not.’

‘And you, Ficelle? Would it suit you to be away from here when the Corpus come calling?’

‘I shall stay at your side, Master.’

The old man smiled. ‘You will better serve me by doing as I ask. I need you to undertake a journey for me. A long journey, fraught with obstacles. Shall you do as I ask?’

The manservant lowered his head. ‘Whatever you ask me I will do.’

The old man watched him for a few moments, seemingly weighing him up. ‘If you fail in this, Ficelle, the consequences will be more terrible than any de Bale – or the Devil he so unwittingly serves – could contrive.’ He hesitated, his hand resting on his grotesquely inflated leg. ‘I have had a vision. Of such clarity that it dwarfs the work to which I have until now dedicated my life. I have held back fifty-eight of my quatrains from publication for reasons which I shall not vouchsafe – they concern only me. Six of these quatrains have a secret purpose – I shall explain to you how to use them. No one must see you. No one must suspect. The remaining fifty-two quatrains must be hidden in a specific place that only you and I can know. I have sealed them inside this bamboo capsule.’ The old man reached down beside his chair and withdrew the packed and tamped tube. ‘You will place this capsule where I tell you, and in exactly the manner I stipulate. You will not deviate from this. You will carry out my instructions to the letter. Is that understood?’

‘Yes, Master.’

The old man lay back in his chair, exhausted by the intensity of what he was trying to communicate. ‘When you return here, after my death, you will go to see my friend and the trustee of my estate, Palamède Marc. You will tell him about your errand and assure him of its success. He will then give you a sum of money. A sum of money that will secure you and your family’s future for generations to come. Do you understand me?’

‘Yes, Master.’

‘Will you trust to my judgement in this matter, and follow my instructions to the letter?’

‘I will’

‘Then you will be blessed, Ficelle. By a people you will never meet, and by a history neither you nor I can remotely envisage.’

‘But you know the future, Master. You are the greatest seer of all time. Even the Queen has honoured you. All France knows of your gifts.’

‘I know nothing, Ficelle. I am like this bamboo tube. Doomed to transmit things but never to understand them. All I can do is pray that there are others, coming after me, who will manage things better.’

PART ONE

1

Quartier St-Denis, Paris, Present Day

Achor Bale took no real pleasure in killing. That had long since left him. He watched the gypsy almost fondly, as one might watch a chance acquaintance getting off an airplane.

The man had been late of course. One only had to look at him to see the vanity bleeding from each pore. The 1950s moustache à la Zorro. The shiny leather jacket bought for fifty euros at the Clignancourt flea market. The scarlet seethrough socks. The yellow shirt with the Prince of Wales plumes and the outsized pointed collar. The fake gold medallion with the image of Sainte Sara. The man was a dandy without taste – as recognisable to one of his own as a dog is to another dog.

‘Do you have the manuscript with you?’

‘What do you think I am? A fool?’

Well, hardly that, thought Bale. A fool is rarely self-conscious. This man wears his venality like a badge of office. Bale noted the dilated pupils. The sheen of sweat on the handsome, razor-sharp features. The drumming of the fingers on the table. The tapping of the feet. A drug addict, then. Strange, for a gypsy. That must be why he needed the money so badly. ‘Are you Manouche or Rom? Gitan, perhaps?’

‘What do you care?’

‘Given your moustache, I’d say Manouche. One of Django Reinhardt’s descendants, maybe?’

‘My name is Samana. Babel Samana.’

‘Your gypsy name?’

‘That is secret.’

‘My name is Bale. No secret there.’

The gypsy’s fingers increased their beat upon the table. His eyes were everywhere now – flitting across the other drinkers, testing the doors, plumbing the dimensions of the ceiling.

‘How much do you want for it?’ Cut straight to the chase. That was the way with a man like this. Bale watched the gypsy’s tongue dart out to moisten the thin, artificially virilised mouth.

‘I want half a million euros.’

‘Just so.’ Bale felt a profound calmness descending upon him. Good. The gypsy really did have something to sell. The whole thing wasn’t just a come-on. ‘For such a sum of money, we’d need to inspect the manuscript before purchase. Ascertain its viability.’

‘And memorise it! Yes. I’ve heard of such things. This much I know. Once the contents are out into the open it’s worthless. Its value lies in its secrecy.’

‘You’re so right. I’m very glad you take that position.’

‘I’ve got someone else interested. Don’t think you’re the only fish in the sea.’

Bale’s eyes closed down on themselves. Ah. He would have to kill the gypsy after all. Torment and kill. He was aware of the telltale twitching above his right eye. ‘Shall we go and see the manuscript now?’

‘I’m talking to the other man first. Perhaps you’ll even bid each other up.’

Bale shrugged. ‘Where are you meeting him?’

‘I’m not saying.’

‘How do you wish to play this then?’

‘You stay here. I go and talk to the other man. See if he’s serious. Then I come back.’

‘And if he’s not? The price goes down?’

‘Of course not. Half a million.’

‘I’ll stay here then.’

‘You do that.’

The gypsy lurched to his feet. He was breathing heavily now, the sweat dampening his shirt at the neck and sternum. When he turned around Bale noticed the imprint of the chair on the cheap leather jacket.

‘If you follow me, I’ll know. Don’t think I won’t.’

Bale took off his sunglasses and laid them on the table. He looked up, smiling. He had long understood the effect his freakishly clotted eyes had on susceptible people. ‘I won’t follow you.’

The gypsy’s mouth went slack with shock. He gazed in horror at Bale’s face. This man had the ia chalou – the evil eye. Babel’s mother had warned him of such people. Once you saw them – once they fixed you with the stare of the basilisk – you were doomed. Somewhere, deep inside his unconscious mind, Babel Samana was acknowledging his mistake – acknowledging that he had let the wrong man into his life.

‘You’ll stay here?’

‘Never fear. I’ll be waiting for you.’

Babel began running as soon as he was out of the café. He would lose himself in the crowds. Forget the whole thing. What had he been thinking of? He didn’t even have the manuscript. Just a vague idea of where it was. When the three ursitory had settled on Babel’s pillow as a child to decide his fate, why had they chosen drugs as his weakness? Why not drink? Or women? Now O Beng had got into him and sent him this cockatrice as a punishment.

Babel slowed to a walk. No sign of the gadje. Had he been imagining things? Imagining the man’s malevolence? The effect of those terrible eyes? Maybe he had been hallucinating? It wouldn’t be the first time he had given himself the heebie-jeebies with badly cut drugs.

He checked the time on a parking meter. Okay. The second man might still be waiting for him. Perhaps he would prove more benevolent?

Across the road, two prostitutes began a heated argument about their respective pitches. It was Saturday afternoon. Pimp day in St-Denis. Babel caught his reflection in a shop window. He gave himself a shaky smile. If only he could swing this deal he might even run a few girls himself. And a Mercedes. He would buy himself a cream Mercedes with red leather seats, can holders and automatic air conditioning. And get his nails manicured at one of those shops where blond payo girls in white pinafores gaze longingly at you across the table.

Chez Minette was only a two-minute walk away. The least he could do would be to poke his head inside the door and check out the other man. Sting him for a down-payment – a proof of interest.

Then, groaning under a mound of cash and gifts, he would go back to the camp and placate his hexi of a sister.

2

Adam Sabir had long since decided that he was on a wild goose chase. Samana was fifty minutes late. It was only his fascination with the seedy milieu of the bar that kept him in situ. As he watched, the barman began winding down the street-entrance shutters.

‘What’s this? Are you closing?’

‘Closing? No. I’m sealing everybody in. It’s Saturday. All the pimps come into town on the train. Cause trouble in the streets. Three weeks ago I lost my front windows. If you want to get out you must leave by the back door.’

Sabir raised an eyebrow. Well. This was certainly a novel way to maintain your customer base. He reached forward and drained his third cup of coffee. He could already feel the caffeine nettling at his pulse. Ten minutes. He would give Samana another ten minutes. Then, although he was still technically on holiday, he would go to the cinema and watch John Huston’s Night of the Iguana – spend the rest of the afternoon with Ava Gardner and Deborah Kerr. Add another chapter to his no doubt unsaleable book on the hundred best films of all time.

‘Une pression, s’il vous plaît. Rien ne presse.

The barman waved a hand in acknowledgement and continued winding. At the last possible moment a lithe figure slid under the descending shutters and straightened up, using a table for support.

‘Ho! Tu veux quoi, toi?’

Babel ignored the barman and stared wildly about the room. His shirt was drenched beneath his jacket and sweat was cascading off the angular lines of his chin. With single-minded intensity he concentrated his attention on each table in turn, his eyes screwed up against the bright interior glare.

Sabir held up a copy of his book on Nostradamus, as they had agreed, with his photograph on prominent display. So. The gypsy had arrived at last. Now for the let-down. ‘I’m over here, Monsieur Samana. Come and join me.’

Babel tripped over a chair in his eagerness to get to Sabir. He steadied himself, limping, his face twisted towards the entrance to the bar. But he was safe for the time being. The shutters were fully down now. He was sealed off from the lying gadje with the crazy eyes. The gadje who had sworn to him that he wouldn’t follow. The gadje who had then trailed him all the way to Chez Minette, not even bothering to hide himself in the crowd. Babel was still in with a chance.

Sabir stood up, a quizzical expression on his face. ‘What’s the matter? You look as though you’ve seen a ghost.’ Close to, all the savagery that he had detected in the gypsy’s stare had transformed itself into a vacant mask of terror.

‘You’re the writer?’

‘Yes. See? That’s me. On the inside back cover.’

Babel reached across to the next table and grabbed an empty beer glass. He smashed it down on to the surface between them and ground his hand in the broken shards. Then he reached across and took Sabir’s hand in his bloodied paw. ‘I’m sorry for this.’ Before Sabir had time to react, the gypsy had forced his hand down on to the broken glass.

‘Jesus! You little bastard…’ Sabir tried to snatch his hand back.

The gypsy clutched hold of Sabir’s hand and pressed it against his own, until the two hands were joined in a bloody scum. Then he smashed Sabir’s bleeding palm against his forehead, leaving a splattered imprint. ‘Now. Listen! Listen to me.’

Sabir wrenched his hand from the gypsy’s grasp. The barman emerged from behind his bar brandishing a foreshortened billiard cue.

‘Two words. Remember them. Samois. Chris.’ Babel backed away from the approaching barman, his bloodied palm held up as if in benediction. ‘Samois. Chris. You remember?’ He threw a chair at the barman, using the distraction to orientate himself in relation to the rear exit. ‘Samois. Chris.’ He pointed at Sabir, his eyes wild with fear. ‘Don’t forget.’

3

Babel knew that he was running for his life. Nothing had ever felt as certain as this before. As complete. The pain in his hand was a violent, throbbing ache. His lungs were on fire, each breath tearing through him as if it were studded with nails.

Bale watched him from fifty metres back. He had time. The gypsy had nowhere to go. No one he could speak to. The Sûreté would take one look at him and put him in a straitjacket – the police weren’t overly charitable to gypsies in Paris, especially gypsies covered in blood. What had happened in that bar? Who had he seen? Well, it wouldn’t take him long to find out.

He spotted the white Peugeot van almost immediately. The driver was asking directions of a window cleaner. The window cleaner was pointing back towards St-Denis and scrunching his shoulders in Gallic incomprehension.

Bale threw the driver to one side and climbed into the cab. The engine was still running. Bale slid the van into gear and accelerated away. He didn’t bother to check in the rear-view mirror.

Babel had lost sight of the gadje. He turned and looked behind him, jogging backwards. Passers-by avoided him, put off by his bloodied face and hands. Babel stopped. He stood in the street, sucking in air like a cornered stag.

The white Peugeot van mounted the kerb and smashed into Babel’s right thigh, crushing the bone. Babel ricocheted off the bonnet and fell heavily on to the pavement. Almost immediately he felt himself being lifted – strong hands on his jacket and the seat of his trousers. A door was opened and he was thrown into the van. He could hear a terrible, high-pitched keening and belatedly realised that it was coming from himself. He looked up just as the gadje brought the heel of his hand up beneath his chin.

4

Babel awoke to an excruciating pain in his legs and shoulders. He raised his head to look around, but saw nothing. It was only then that he realised that his eyes were bandaged and that he was tied, upright, to some sort of metal frame from which he hung forward, his legs and arms in cruciform position, his body in an involuntary semicircle, as though he were thrusting out his hips in the course of some particularly explicit dance. He was naked.

Bale gave Babel’s penis another tug. ‘So. Have I got your attention at last? Good. Listen to me, Samana. There are two things you must know. One. You are definitely going to die – you cannot possibly talk your way out of this or buy your life from me with information. Two. The manner of your death depends entirely on you. If you please me, I will cut your throat. You won’t feel anything. And the way I do it, you will bleed to death in under a minute. If you displease me, I will hurt you – far more than I am hurting you now. To prove to you that I intend to kill you – and that there is no way back from the position in which you find yourself – I am going to slice your penis off. Then I shall cauterise the wound with a hot iron so that you don’t bleed to death before your time.’

‘Don’t! Don’t do it! I will tell you anything you want to know. Anything.’

Bale stood with his knife held flat against the outstretched skin of Babel’s member. ‘Anything? Your penis, against the information that I seek?’ Bale shrugged his shoulders. ‘I don’t understand. You know that you will never use it again. I have made this quite clear. Why should you wish to retain it? Don’t tell me that you are still labouring under the delusion that there is hope?’

A filament of saliva drooled from the edge of Babel’s mouth. ‘What do you want me to tell you?’

‘First. The name of the bar.’

‘Chez Minette.’

‘Good. That is correct. I saw you enter there myself. Who did you see?’

‘An American. A writer. Adam Sabir.’

‘Why?’

‘To sell him the manuscript. I wanted money.’

‘Did you show him the manuscript?’

Babel gave a fractured laugh. ‘I don’t even have it. I’ve never seen it. I don’t even know if it exists.’

‘Oh dear.’ Bale let go of Babel’s penis and began stroking his face. ‘You are a handsome man. The ladies like you. A man’s greatest weakness always lies in his vanity.’ Bale criss-crossed his knife blade over Babel’s right cheek. ‘Not so pretty now. From one side, you’ll still do. From the other – Armageddon. Look. I can put my finger right through this hole.’

Babel started screaming.

‘Stop. Or I shall mark the other side.’

Babel stopped screaming. Air fluttered through the torn flaps of his cheek.

‘You advertised the manuscript. Two interested parties answered. I am one. Sabir the other. What did you intend to sell to us for half a million euros? Hot air?’

‘I was lying. I know where it can be found. I will take you to it.’

‘And where is that?’

‘It’s written down.’

‘Recite it to me.’

Babel shook his head. ‘I can’t.’

‘Turn the other cheek.’

‘No! No! I can’t. I can’t read…’

‘How do you know it’s written down then?’

‘Because I’ve been told.’

‘Who has this writing? Where can it be found?’ Bale cocked his head to one side. ‘Is a member of your family hiding it? Or somebody else?’ There was a pause. ‘Yes. I thought so. I can see it on your face. It’s a member of your family, isn’t it? I want to know who. And where.’ Bale grabbed hold of Babel’s penis. ‘Give me a name.’

Babel hung his head. Blood and saliva dripped out of the hole made by Bale’s knife. What had he done? What had his fear and bewilderment made him reveal? Now the gadje would go and find Yola. Torture her too. His dead parents would curse him for not protecting his sister. His name would become unclean – mahrimé. He would be buried in an unmarked grave. And all because his vanity was stronger than his fear of death.

Had Sabir understood those two words he had told him in the bar? Would his instincts about the man prove right?

Babel knew that he had reached the end of the road. A lifetime spent building castles in the air meant that he understood his own weaknesses all too well. Another thirty seconds and his soul would be consigned to hell. He would have only one chance to do what he intended to do. One chance only.

Using the full hanging weight of his head, Babel threw his chin up to the left, as far as it could stretch, and then wrenched it back downwards in a vicious semicircle to the right.

Bale took an involuntary step backwards. Then he reached across and grabbed a handful of the gypsy’s hair. The head lolled loose, as if sprung from its moorings. ‘Nah!’ Bale let the head drop forward. ‘Impossible.’

Bale walked a few steps away, contemplated the corpse for a second and then approached again. He bent forwards and filleted the gypsy’s ear with his knife. Then he slid off the blindfold and thumbed back the man’s eyelids. The eyes were dull – no spark of life.

Bale cleaned his knife on the blindfold and walked away, shaking his head.

5

Captain Joris Calque of the Police Nationale ran the unlit cigarette beneath his nose, then reluctantly replaced it in its gunmetal case. He slid the case into his jacket pocket. ‘At least this cadaver’s good and fresh. I’m surprised blood isn’t still dripping from its ear.’ Calque stubbed his thumb against Babel’s chest, withdrew it, then craned forwards to monitor for any colour changes. ‘Hardly any lividity. This man hasn’t been dead for more than an hour. How did we get to him so fast, Macron?’

‘Stolen van, Sir. Parked outside. The van owner called it in and a pandore on the beat ran across it forty minutes later. I wish all street crime was as easy to detect.’

Calque stripped off his protective gloves. ‘I don’t understand. Our murderer kidnaps the gypsy from the street, in full public view, and in a stolen van. Then he drives straight here, strings the gypsy up on a bed frame that he has conveniently nailed to the wall before the event, tortures him a little, breaks his neck, and then leaves the van parked out in the street like a signpost. Does that make any sense to you?’

‘We also have a blood mismatch.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘Here. On the victim’s hand. These cuts are older than the other wounds. And there is alien blood mixed in with the victim’s own. It shows up clearly on the portable spectrometer.’

‘Ah. So now, not satisfied with the van signpost, the killer leaves us a blood signpost too.’ Calque shrugged. ‘The man is either an imbecile or a genius.’

6

The pharmacist finished bandaging Sabir’s hand. ‘It must have been cheap glass – you’re lucky not to need any stitches. You’re not a pianist, by any chance?’

‘No. A writer.’

‘Oh. No skills involved, then.’

Sabir burst out laughing. ‘You could say that. I’ve written one book about Nostradamus. And now I write film reviews for a chain of regional newspapers. But that’s about it. The sum total of a misspent life.’

The pharmacist snatched a hand to her mouth. ‘I’m so sorry. I didn’t mean what you think I meant. Of course writers are skilful. I meant digital skills. The sort in which one needs to use one’s fingers.’

‘It’s all right.’ Sabir stood up and eased on his jacket. ‘We hacks are used to being insulted. We are resolutely bottom of the pecking order. Unless we write bestsellers, that is, or contrive to become celebrities, when we magically spring to the top. Then, when we can’t follow up, we sink back down to the bottom again. It’s a heady profession, don’t you agree?’ He disguised his bitterness behind a broad smile. ‘How much do I owe you?’

‘Fifty euros. If you’re sure you can afford it, that is.’

‘Ah. Touché! Sabir took out his wallet and riffled through it for notes. Part of him was still struggling to understand the gypsy’s actions. Why would a man attack a total stranger? One he was hoping would buy something valuable off him? It made no earthly sense. Something was preventing him from going to the police, however, despite the encouragement of the barman and the three or four customers who had witnessed the attack. There was more to this than met the eye. And who or what were Samois and Chris? He handed the pharmacist her money. ‘Does the word Samois mean anything to you?’

‘Samois?’ The pharmacist shook her head. ‘Apart from the place, you mean?’

‘The place? What place?’

‘Samois-sur-Seine. It’s about sixty kilometres southeast of here. Just above Fontainebleau. All the jazz people know it. The gypsies hold a festival there every summer in honour of Django Reinhardt. You know. The Manouche guitarist.’

‘Manouche?’

‘It’s a gypsy tribe. Linked to the Sinti. They come from Germany and northern France. Everybody knows that.’

Sabir gave a mock bow. ‘But you forget, Madame. I’m not everybody. I’m only a writer.’

7

Bale didn’t like barmen. They were an obnoxious species, living off the weakness of others. Still. In the interests of information-gathering he was prepared to make allowances. He slipped the stolen ID back inside his pocket. ‘So the gypsy attacked him with a glass?’

‘Yes. I’ve never seen anything like it. He just came in, leaking sweat, and made a beeline for the American. Smashed up a glass and ground his hand in it.’

‘The American’s?’

‘No. That was the odd thing. The gypsy ground his own hand in it. Only then did he attack the American.’

‘With the glass?’

‘No. No. He took the American’s hand and did the same thing with it as he’d done with his own. Then he forced the American’s hand on to his forehead. Blood all over the place.’

‘And that was it?’

‘Yes.’

‘He didn’t say anything?’

‘Well, he was shouting all the time. “Remember these words. Remember them.’”

‘What words?’

‘Ah. Well. There you have me. It sounded like Sam, moi, et Chris. Perhaps they’re brothers?’

Bale suppressed a triumphant smile. He nodded his head sagely. ‘Brothers. Yes.’

8

The barman tossed his hands up melodramatically. ‘But I’ve just talked to one of your officers. Told him everything I know. Do you people want me to change your nappies for you as well?’

‘And what did this officer look like?’

‘Like you all look.’ The barman shrugged. ‘You know.’

Captain Calque glanced over his shoulder at Lieutenant Macron. ‘Like him?’

‘No. Nothing like him.’

‘Like me, then?’

‘No. Not like you.’

Calque sighed. ‘Like George Clooney? Woody Allen? Johnny Halliday? Or did he wear a wig, perhaps?’

‘No. No. He didn’t wear a wig.’

‘What else did you tell this invisible man?’

‘Now there’s no need to be sarcastic. I’m doing my duty as a citizen. I tried to protect the American…’

‘With what?’

‘Well… My billiard cue.’

‘Where do you keep this offensive weapon?’

‘Where do I keep it? Where do you think I keep it? Behind the bar, of course. This is St-Denis, not the SacréCoeur.’

‘Show me.’

‘Look. I didn’t hit anybody with it. I only waved it at the gypsy.’

‘Did the gypsy wave back?’

‘Ah. Merde.’ The barman slit open a pack of Gitanes with the bar ice-pick. ‘I suppose you’ll have me up for smoking in a public place next? You people.’ He blew a cloud of smoke across the counter.

Calque relieved the barman of one of his cigarettes. He tapped the cigarette on the back of the packet and ran it languorously beneath his nose.

‘Aren’t you going to light that?’

‘No.’

‘Putain. Don’t tell me you’ve given up?’

‘I have a heart condition. Each cigarette takes a day off my life.’

‘Worth it though.’

Calque sighed. ‘You’re right. Give me a light.’

The barman offered Calque the tip of his cigarette. ‘Look. I’ve remembered now. About your officer.’

‘What have you remembered?’

‘There was something strange about him. Very strange.’

‘And what was that?’

‘Well. You won’t believe me if I tell you.’

Calque raised an eyebrow. ‘Try me.’

The barman shrugged. ‘He had no whites to his eyes.’

9

‘The man’s name is Sabir. S.A.B.I.R. Adam Sabir. An American. No. I have no more information for you at this time. Look him up on your computer. That should be quite enough. Believe me.’

Achor Bale put down the telephone. He allowed himself a brief smile. That would sort Sabir. By the time the French police were through with questioning him, he would be long gone. Chaos was always a good idea. Chaos and anarchy. Foment those, and you forced the established forces of law and order on to the back foot.

Police and public administrators were trained to think in a linear fashion – in terms of rules and regulations. In computer terms, hyper was the opposite of linear. Well then. Bale prided himself on his ability to think in a hyper fashion – skipping and jumping around wherever he fancied. He would do whatever he wanted to do, whenever he wanted to do it.

He reached across for a map of France and spread it neatly out on to the table in front of him.

10

The first Adam Sabir knew of the Sûreté’s interest in him was when he switched on the television set in his rented flat on the Ile St-Louis and saw his own face, full-size, staring back at him from the plasma screen.

As a writer and occasional journalist, Sabir needed to keep up with the news. Stories lurked there. Ideas simmered. The state of the world was reflected in the state of his potential market, and this concerned him. In recent years he had got into the habit of living to a very comfortable standard indeed, thanks to a freak one-off bestseller called The Private Life of Nostradamus.The original content had been just about nil – the title a stroke of genius. Now he desperately needed a follow-up or the money tap would turn off, the luxury lifestyle dry up, and his public melt away.

Samana’s advertisement in that ludicrous free rag of a newspaper, two days before, had captured his attention, therefore, because it was so incongruous and so entirely unexpected:

Money needed. I have something to sell. Notre Dame’s [sic] lost verses. All written down. Cash sale to first buyer. Genuine.

Sabir had laughed out loud when he first saw the ad – it had so obviously been dictated by an illiterate. But how would an illiterate know about Nostradamus’s lost quatrains?

It was common knowledge that the sixteenth-century seer had written 1,000 indexed four-line verses, published during his lifetime, and anticipating, with an almost preternatural accuracy, the future course of world events. Less well known, however, was the fact that fifty-eight of the quatrains had been held back at the very last moment, never to see the light of day. If an individual could find the location of those verses, they would become an instant millionaire – the potential sales were stratospheric.

Sabir knew that his publisher would have no compunction in anteing up whatever sum was needed to cement such a sale. The story of the find alone would bring in hundreds of thousands of dollars in newspaper revenue, and would guarantee front-page coverage all over the world. And what wouldn’t people give, in this uncertain age, to read the verses and understand their revelations? The mind boggled.

Until the events of today, Sabir had happily fantasised a scenario in which his original manuscript, like the Harry Potter books before him, would be locked up in the literary equivalent of a Fort Knox, only to be revealed to the impatiently slavering hordes on publication day. He was already in Paris. What would it cost him to check the story out? What did he have to lose?

Following the brutal torture and murder of an unknown male, police are seeking the American writer Adam Sabir, who is wanted for questioning in connection with the crime. Sabir is believed to be visiting Paris, but should under no circumstances be approached by members of the public, as he may be dangerous. The quality of the crime is of so serious a nature that the Police Nationale are making it their priority to identify the murderer, who, it is strongly believed, may be preparing to strike again.

‘Oh Jesus.’ Sabir stood in the centre of his living room and stared at the television set as if it might suddenly decide to break free from its moorings and crawl across the floor towards him. An old publicity photo of himself was taking up the full extent of the screen, exaggerating every feature of his face until he, too, could almost believe that it depicted a wanted criminal.

A death-mask ‘Do You Know this Man?’ photograph of Samana followed, its cheek and ear lacerated, its eyes dully opened, as if its owner were sitting in judgement on the millions of couch-potato voyeurs taking fleeting comfort from the fact that it was someone else, and not they, depicted over there on the screen.

‘It’s not possible. My blood’s all over him.’

Sabir sat down in an armchair, his mouth hanging open, the throbbing in his hand uncannily echoing the throbbing of the linking electronic music that was even now accompanying the closing headlines of the evening news.

11

It took him ten frenetic minutes to gather all his belongings together – passport, money, maps, clothes, and credit cards. At the very last moment he rifled through the desk in case there was anything in there he might use.

He was borrowing the flat from his English agent, John Tone, who was on holiday in the Caribbean. The car was his agent’s, too, and therefore unidentifiable – its very anonymity might at least suffice to get him out of Paris. To buy him time to think.

He hastily pocketed an old British driving licence in Tone’s name and some spare euros he found in an empty film canister. No photograph on the driving licence. Might be useful. He took an electricity bill and the car papers, too.

If the police apprehended him he would simply plead ignorance – he was starting on a research trip to St-Rémy-de-Provence, Nostradamus’s birthplace. He hadn’t listened to the radio or watched the TV – didn’t know the police were hunting for him.

With luck he could make it as far as the Swiss border – bluster his way through. They didn’t always check passports there. And Switzerland was still outside the European Union. If he could make it as far as the US Embassy in Bern he would be safe. If the Swiss extradited him to anywhere, it would be to the US, not to Paris.

For Sabir had heard tales about the French police from some of his journalist colleagues. Once you got into their hands, your number was up. It could take months or even years for your case to make its way through the bureaucratic nightmare of the French jurisdictional system.

He stopped at the first hole-in-the-wall he could find and left the car engine running. He’d simply have to take the chance and get some cash. He stuffed the first card through the slit and began to pray. So far so good. He’d try for a thousand euros. Then, if the second card failed him, he could at least pay the motorway tolls in untraceable cash and get himself something to eat.

Across the street, a youth in a hoodie was watching him. Christ Jesus. This was hardly the time to get mugged. And with the keys left in a brand-new Audi station wagon, with the engine running.

He pocketed the cash and tried the second card. The youth was moving towards him now, looking about him in that particular way young criminals had. Fifty metres. Thirty. Sabir punched in the numbers.

The machine ate the card. They were closing him down.

Sabir darted back towards the car. The youth had started running and was about five metres off.

Sabir threw himself inside the car, and only then remembered that it was British made, with the steering wheel placed on the right. He plunged across the central divider and wasted three precious seconds searching around for the unfamiliar central locking system.

The youth had his hand on the door.

Sabir crunched the automatic shift into reverse and the car lurched backwards, throwing the teenager temporarily off balance. Sabir continued backwards up the street, one foot twisted behind him on to the passenger seat, his free hand clutching the steering wheel.

Ironically he found himself thinking not about the mugger – a definite first, in his experience – but about the fact that, thanks to his forcibly abandoned bank card, the police would now have his fingerprints, and a precise location of his whereabouts, at exactly 10.42 p.m., on a clear and starlit Saturday night, in central Paris.

12

Twenty minutes out of Paris, and five minutes shy of the Evry autoroute junction, Sabir’s attention was caught by a road sign – thirty kilometres to Fontainebleau. And Fontainebleau was only ten short kilometres downriver from Samois. The pharmacist had told him so. They’d even had a brief, mildly flirtatious discussion about Henri II, Catherine de Medici, and Napoleon, who had apparently used the place to bid farewell to his Old Guard before leaving for exile on Elba.

Better to forget the autoroute and head for Samois. Didn’t they have number-plate recognition on the autoroutes? Hadn’t he heard that somewhere? What if they had already traced him to Tone’s flat? It wouldn’t be long before they connected him with Tone’s Audi, too. And then they’d have him cold.

If he could only get the quatrains from this Chris person, he might at least be able to persuade the police that he was, indeed, a bona fide writer, and not a psycho on the prowl. And why should the gypsy’s death have had anything to do with the verses anyway? Such people were always engaging in feuds, weren’t they? It was probably only an argument over money or a woman and he, Sabir, had simply got in the way of it. When you looked at it like that, the whole thing took on a far more benevolent aspect.

Anyway, he had an alibi. The pharmacist would remember him, surely? He’d told her all about the gypsy’s behaviour. It simply didn’t make sense for him to have tortured and killed the gypsy with his hand torn to shreds like that. The police would see that, wouldn’t they? Or would they think he’d followed the gypsy and taken revenge on him after the bar fight?

Sabir shook his head. One thing was for certain. He needed rest. If he carried on like this he would begin to hallucinate.

Forcing himself to stop thinking and to start acting, Sabir slewed the car across the road and down a woodland track, just two kilometres short of the village of Samois itself.

13

‘He’s slipped the net.’

‘What do you mean? How do you know that?’

Calque raised an eyebrow. Macron was certainly coming on – no doubt about that. But imagination? Still, what could one expect from a two-metre-tall Marseillais? ‘We’ve checked all the hotels, guest houses and letting agencies. When he arrived here he had no reason to conceal his name. He didn’t know he was going to kill the gypsy. This is an American with a French mother, remember. He speaks our language perfectly. Or at least that’s what the fool claims on his website. Either he’s gone to ground in a friend’s house, or he’s bolted. My guess is that he’s bolted. In my experience it’s a rare friend who’s prepared to harbour a torturer.’

‘And the man who telephoned in his name?’

‘Find Sabir and we’ll find him.’

‘So we stake out Samois? Look for this Chris person?’

Calque smiled. ‘Give the girlie a doll.’

14

The first thing Sabir saw was a solitary deerhound crossing the ride in front of him, lost from the previous day’s exercise. Below him, dissected by trees, the River Seine sparkled in the early morning sun.

He climbed out of the car and stretched his legs. Five hours’ sleep. Not bad in the circumstances. Last night he’d felt nervous and on edge. Now he felt calmer – less panic-stricken about his predicament. It had been a wise move to take the turning to Samois, and even wiser to pull over into the forest to sleep. Perhaps the French police wouldn’t run him to ground so easily after all? Still. Wouldn’t do to take unnecessary risks.

Fifty metres down the track, with the car windows open, he picked up woodsmoke and the unmistakable odour of fried pork fat. At first he was tempted to ignore it and continue on his way, but hunger prevailed. Whatever happened, he had to eat. And why not here? No cameras. No cops.

He instantly convinced himself that it would make perfect sense to offer to buy his breakfast direct from whoever happened to be doing the cooking. The mystery campers might even be able to point him towards Chris.

Abandoning the car, Sabir cut through the woods on foot, following his nose. He could feel his stomach expanding towards the smell of the bacon. Crazy to think that he was on the run from the police. Perhaps, being campers, these people wouldn’t have had access to a television or a newspaper?

Sabir stood for some time on the edge of the clearing, watching. It was a gypsy camp. Well. He’d lucked into it, really. He should have realised that no one in their right mind would have been camping out in a northern manorial forest in early May. August was the time for camping – otherwise, if you were French, you stayed in a hotel with your family and dined in comfort.

One of the women saw him and called out to her husband. A bunch of children came running towards him and then stopped, in a gaggle. Two other men broke off from what they were doing and started in his direction. Sabir raised a hand in greeting.

The hand was pulled violently from behind him and forced to the rear of his neck. He felt himself being driven down to his knees.

Just before he lost consciousness he noticed the television mast on one of the caravans.

15

‘You do it, Yola. It’s your right.’

The woman was standing in front of him. An older man placed a knife in her hand and shooed her forward. Sabir tried to say something but he found that his mouth was taped shut.

‘That’s it. Cut off his balls.’ ‘No. Do his eyes first.’ A chorus of elderly women were encouraging her from their position outside the caravan doorway. Sabir looked around. Apart from the woman with the knife, he was surrounded entirely by men. He tried to move his arms but they were bound tightly behind his back. His ankles were knotted together and a decorated pillow had been placed between his knees.

One of the men upended him and manhandled his trousers over his hips. ‘There. Now you can see the target.’

‘Stick it up his arse while you’re at it.’ The old women were pushing forward to get a better view.

Sabir began shaking his head in a futile effort to free the tape from his mouth.

The woman began inching forward, the knife held out in front of her.

‘Go on. Do it. Remember what he did to Babel.’

Sabir began a sort of ululation from inside his taped mouth. He fixed his eyes on the woman in fiendish concentration, as if he could somehow will her not to follow through with what she intended.

Another man grabbed Sabir’s scrotum and stretched it away from his body, leaving only a thin membrane of skin to be cut. A single blow of the knife would be enough.

Sabir watched the woman. Instinct told him that she was his only chance. If his concentration broke and he looked away, he knew that he was done for. Without fully understanding his own motivation, he winked at her.

The wink hit her like a slap. She reached forward and ripped the tape off Sabir’s mouth. ‘Why did you do that? Why did you mutilate my brother? What had he done to you?’

Sabir dragged a great gulp of air through his swollen lips. ‘Chris. Chris. He told me to ask for Chris.’

The woman stepped backwards. The man holding Sabir’s testicles let go of them and leaned across him, his head cocked to one side like a bird dog. ‘What’s that you say?’

‘Your brother smashed a glass. He pressed his hand into it. Then mine. Then he ground our two hands together and placed the imprint of mine on his forehead. He then told me to go to Samois and ask for Chris. I wasn’t the one that killed him. But I realise now that he was being followed. Please believe me. Why should I come here otherwise?’

‘But the police. They are looking for you. We saw on the television. We recognised your face.’

‘My blood was on his hand.’

The man threw Sabir to one side. For a moment Sabir was convinced that they were going to slit his throat. Then he could feel them unbandaging his hand – inspecting the cuts. Hear them talking to each other in a language he could not understand.

‘Stand up. Put your trousers on.’

They were cutting the ropes behind his back.

One of the men prodded him. ‘Tell me. Who is Chris?’

Sabir shrugged. ‘One of you, I suppose.’

Some of the older men laughed.

The man with the knife winked at him, in unconscious echo of the wink that had saved Sabir’s testicles two short minutes before. ‘Don’t worry. You’ll meet him soon. With or without your balls. The choice is yours.’

16

At least they’re feeding me, thought Sabir. It’s harder to kill a man you’ve broken bread with. Surely.

He spooned up the last of the stew, then reached down with his manacled hands for his coffee. ‘The meat. It was good.’

The old woman nodded. She wiped her hands on her voluminous skirts but Sabir noticed that she did not eat. ‘Clean. Yes. Very clean.’

‘Clean?’

‘The spines. Hedgehogs are the cleanest beasts. They are not mahrimé. Not like…’ She spat over her shoulder. ‘Dogs.’

‘Ah. You eat dogs?’ Sabir was already having problems with the thought of hedgehogs. He could feel the onset of nausea threatening.

‘No. No.’ The woman burst into uproarious laughter. ‘Dogs. Hah hah.’ She signalled to one of her friends. ‘Heh. The gadje thinks we eat dogs.’

A man came running into the clearing. He was instantly surrounded by young children. He spoke to a few of them and they peeled off to warn the camp.

Sabir watched intently as boxes and other objects were swiftly secreted beneath and inside the caravans. Two men broke off from what they were doing and came towards him.

‘What is it? What’s happening?’

They picked him up between them and carried him, splay-legged, towards a wood-box.

‘Jesus Christ. You’re not going to put me in there?

I’m claustrophobic. Seriously. I promise. I’m not good in narrow places. Please. Put me in one of the caravans.’

The men tumbled him inside the wood-box. One of them drew a stained handkerchief from his pocket and thrust it into Sabir’s mouth. Then they eased his head beneath the surface of the box and slammed shut the lid.

17

Captain Calque surveyed the disparate group in front of him. He was going to have trouble with this lot. He just knew it. Knew it in his bones. Gypsies always shut up shop when talking to the police – even when it was one of their own who had been the victim of a crime, as in this case. Still they persisted in wanting to take the law into their own hands.

He nodded to Macron. Macron held up the photograph of Sabir.

‘Have any of you seen this man?’

Nothing. Not even a nod of recognition.

‘Do any of you know who this man is?’

‘A killer.’

Calque shut his eyes. Oh well. At least someone had actually spoken to him. Addressed a comment to him. ‘Not necessarily. The more we find out, the more it seems that there may be a second party involved in this crime. A party whom we have not yet succeeded in identifying.’

‘When are you going to release my brother’s body so that we can bury him?’

The men were making way for a young woman – she manoeuvred herself through the closed ranks of women and children and moved to the forefront of the group.

‘Your brother?’

‘Babel Samana.’

Calque nodded to Macron, who began writing vigorously in a small black notebook. ‘And your name?’

‘Yola. Yola Samana.’

‘And your parents?’

‘They are dead.’

‘Any other relatives?’

Yola shrugged, and indicated the surrounding sea of faces.

‘Everyone?’

She nodded.

‘So what was he doing in Paris?’

She shrugged again.

‘Anyone know?’

There was a group shrug.

Calque was briefly tempted to burst out laughing – but the fact that the assembly would probably lynch him if he were to do so, prevented him from giving in to the emotion. ‘So can anyone tell me anything at all about Samana? Who he was seeing – apart from this man Sabir, of course. Or why he was visiting St-Denis?’

Silence.

Calque waited. Thirty years of experience had taught him when, and when not, to press an issue.

‘When are you giving him back?’

Calque summoned up a fake sigh. ‘I can’t tell you that exactly. We may need his body for further forensic tests.’

The young woman turned to one of the older male gypsies. ‘We must bury him within three days.’

The gypsy hitched his chin at Calque. ‘Can we have him?’

‘I told you. No. Not yet.’

‘Can we have some of his hair then?’

‘What?’