6,84 €

Mehr erfahren.

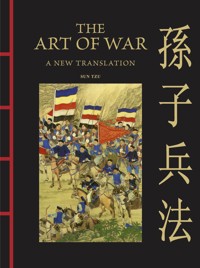

- Herausgeber: Amber Books Ltd

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Serie: Chinese Bound

- Sprache: Englisch

Written in the 6th century BC, Sun Tzu’s The Art of War is still used as a book of military strategy today. Napoleon, Mae Zedong, General Vo Nguyen Giap and General Douglas MacArthur all claimed to have drawn inspiration from it. And beyond the world of war, business and management gurus have also applied Sun Tzu’s ideas to office politics and corporate strategy. Using a new translation by James Trapp and including editorial notes, this bilingual edition of The Art of War lays the original Chinese text opposite the modern English translation. The book contains the full original 13 chapters on such topics as laying plans, attacking by stratagem, weaponry, terrain and the use of spies. Sun Tzu addresses different campaign situations, marching, energy and how to exploit your enemy’s weaknesses. Of immense influence to great leaders across millennia, The Art of War is a classic text richly deserving this exquisite edition.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 64

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

www.amberbooks.co.uk

This digital edition first published in 2012

Published by Amber Books Ltd United House North Road London N7 9DP United Kingdom

Website: www.amberbooks.co.uk Instagram: amberbooksltd Facebook: amberbooks Twitter: @amberbooks

Copyright © 2012 Amber Books Ltd

ISBN: 978 190 916 019 4

Text: James Trapp Project Editor: Michael Spilling Design: Rajdip Sanghera

All rights reserved. With the exception of quoting brief passages for the purpose of review no part of this publication may be reproduced without prior written permission from the publisher. The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. All recommendations are made without any guarantee on the part of the author or publisher, who also disclaim any liability incurred in connection with the use of this data or specific details.

Contents

Introduction

計篇

Planning

作戰篇

Waging War

謀攻篇

Strategic Offence

形篇

Deployment

勢篇

Momentum

虛實篇

The Substantial and the Insubstantial

軍爭篇

Manoeuvres against the Enemy

九變篇

The Nine Variables

行軍篇

On the March

地形篇

Terrain

九地篇

The Nine Types of Ground

火攻篇

Attacking with Fire

用間篇

Using Spies

Introduction

It is an unusual book that was written 2500 years ago in an impenetrable classical language and yet figures on the recommended reading list of the United States Marine Corps. More unusual still for it to be a favourite book of figures so contrasting as General Douglas MacArthur and Mao Zedong (Mao Tse Tung); but Sunzi’s 兵法 [Art of War] is such a book. Moreover it has discovered a new life outside military circles in the world of modern business management. A simple internet search under ‘Art of War + business strategy’ will provide hundreds of sites claiming to offer invaluable commercial insights based on this ancient text.

According to long tradition, 兵法 was written by Sun Wu, better known as Sunzi (Sun Tzu in the old style Romanization), a general and strategist in the service of King He Lü of Wu during the Spring and Autumn Annals period of ancient China (770–476 BCE). The accuracy of this version is, however, a matter of heated scholarly debate, with some experts believing that inconsistencies and anachronisms in the text point to a later date of composition, and others questioning even the existence of Sunzi as a historical figure. Further confusing the matter is the existence of a later text from the second half of the fourth century BCE, also called the Art of War, written by a man called Sun Bin, who was also known as Sunzi.

There is no definitive standard text of the Art of War; over centuries of copying, minor variations have crept in, as is the case with most ancient manuscripts. Furthermore, classical Chinese was written without punctuation, which serves to increase the number of possible readings. There are also a number of places where the text is indisputably corrupt. All this, added to the potential ambiguity of the actual language of classical Chinese, means that no two interpretations of Art of War are alike. In this translation I have used one of the most widely accepted versions of the text from the Song Dynasty period (960–1279 CE), and where conflicting interpretations exist, have attempted to allow context and the balance of the prose to dictate my translation.

“There is no absolutely standard text for the Art of War; over centuries of copying, minor variations have crept in…”

The structure of the text is generally undisputed. It is divided into 13 chapters, each addressing an aspect of organization or strategic planning. Some of these chapters are more sophisticated and clearly complete than others, indicating again the likelihood of corruption in the text. All of them, however, are at one level intensely practical, especially Sunzi’s observations on interpreting the mood of soldiers (both one’s own and the enemy’s) from their behaviour. What is notable throughout and what raises the work far above a simple military manual is the elegance of the prose and the underlying Daoist principles. In the eyes of Sunzi, a general is no mere jobbing soldier: he is a scholar, gentleman and philosopher. The depth of meaning which this element of mysticism imparts is undoubtedly responsible for the work’s continuing and universal appeal.

Sunzi Said 1…

1 Throughout the text wherever Chinese names or other words appear, I have adopted the modern pinyin romanization. Thus Sunzi rather than the traditional form Sun Tzu. Although doubts may be raised about the historical authenticity of the attribution, the author of the Art of War is traditionally believed to be Sun Wu, known later as Sunzi, a distinguished general in the service of King He Lü of Wu in the sixth century BCE during the period known as the Spring and Autumn Annals (770 - 476 BCE). The content of the text and the types of warfare it describes, however, suggest to many scholars that it was in fact written in the later Warring States period (475 - 221 BCE).

計篇

孫子曰:兵者,國之大事,死生之地,存亡之道, 不可不察也。

故經之以五,校之以計,而索其情:一曰道,二曰 天,三曰地,四曰 將,五曰法。

Planning

“…War is the place where life and death meet…”

Understanding the nature of war is of vital importance to the State. War is the place where life and death meet; it is the road to destruction or survival. It demands study. War has five decisive factors, which you must take into account in your planning; you must fully understand their relevance. First is a Moral Compass; second is Heaven; third is Earth; fourth is the Commander; fifth is Regulation.

道者,令民于上同意者也,可與之死,可與之 生,民不 詭也。天者,陰陽、寒暑、時制也。 地者,高下、遠近、險易、廣狹、死生也。將 者,智、信、仁、勇、嚴也。法者,曲制、官 道、主用也。

凡此五者,將莫不聞,知之者勝,不知之者不 勝。故校之以計,而索其情。曰:主孰有道?將 孰有能?天地孰得?法令孰行?兵眾孰 強?士卒 孰練?賞罰孰明?吾以此知勝負矣。

“The General must be possessed of wisdom, honesty, benevolence, courage and discipline.”

A Moral Compass brings the people into accord with their ruler so that they will follow him in life and in death without fear.

Heaven encompasses night and day, heat and cold and the changing of the seasons.

Earth encompasses nearness and distance, ease and hindrance, wide plains and narrow gorges – matters of life or death.

The General must be possessed of wisdom, honesty, benevolence, courage and discipline.2

Regulation means the marshalling of the army, correct organization and control of supplies.

A General must pay attention to all five, for they represent the difference between defeat and victory.

So you must study them when laying your plans and thoroughly understand their relevance. By this I mean you should consider:

Which Ruler has a Moral Compass? Which General has ability? Which side is best favoured by climate and terrain? Where is leadership most effective? Which army is strongest? Whose officers and men are best trained? Who best understands the use of reward and punishment? The answers to these questions tell me who will succeed and who will be defeated.

2 Although the Art of War is essentially a practical handbook, Sunzi incorporates philosophical principles from both Confucianism and Daoism. The character I have translated as “moral compass” is 道 dào which is the “True Way” of Laozi and Daoism, and clearly here shares something of the same meaning. The five qualities essential in a general are pretty much the military equivalents of the Five Confucian Virtues.

將聽吾計,用之必勝,留之;將不聽吾計,用之必 敗,去之。

計利以聽,乃為之勢,以佐其外。勢者,因利而 制權也。

兵者,詭道也。故能而示之不能,用而示之不 用,近而示之遠,遠而 示之近。利而誘之,亂而 取之,實而備之,強而避之,怒而撓之,卑 而驕之,佚而勞之,親而離之,攻其不備,出其不 意。此兵家之勝, 不可先傳也。

夫未戰而廟算勝者,得算多也;未戰而廟算不勝 者,得算少也。多算 勝,少算不勝,而況無算 乎!吾以此觀之,勝負見矣。

You should retain those of your generals who heed this advice, for they will be victorious; you should dismiss those who do not, for they will be defeated.