5,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Amber Books Ltd

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

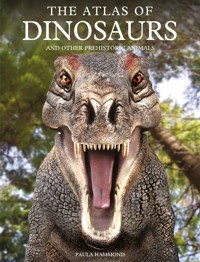

Each year we learn more about life on earth hundreds of millions of years ago. Illustrated with full-colour photographs and colour artworks, The Atlas of Dinosaurs features current paleontological research on dinosaurs from every period and every region of the planet – from little known early dinosaurs to the best known ones such as Iguanodon and Tyrannosaurus Rex, from the smallest to the largest, from aquatic dinosaurs to prehistoric birds, and from herbivores, to carnivores to omnivores.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 221

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

THE ATLAS OF

DINOSAURS

AND OTHER PREHISTORIC ANIMALS

PAULA HAMMOND

This digital edition first published in 2019

Published by

Amber Books Ltd

United House

North Road

London N7 9DP

United Kingdom

Website: www.amberbooks.co.uk

Instagram: amberbooksltd

Facebook: amberbooks

Twitter: @amberbooks

Copyright © 2019 Amber Books Ltd

ISBN: 978-1-78274-234-0

Picture Credits

Artwork credits: All © International Masters Publishing Ltd

All other images and illustrations © Amber Books

All rights reserved. With the exception of quoting brief passages for the purpose of review no part of this publication may be reproduced without prior written permission from the publisher.

The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. All recommendations are made without any guarantee on the part of the author or publisher, who also disclaim any liability incurred in connection with the use of this data or specific details.

www.amberbooks.co.uk

Contents

INTRODUCTION

THE TRIASSIC PERIOD

CYNOGNATHUS

GRACILISUCHUS

COELOPHYSIS

HERRERASAURUS

POSTOSUCHUS

LYSTROSAURUS

THE EARLY TO MIDDLE JURASSIC PERIOD

CRYOLOPHOSAURUS

DILOPHOSAURUS

DIMORPHODON

MEGALOSAURUS

OPHTHALMOSAURUS

SCELIDOSAURUS

SHUNOSAURUS

THE LATE JURASSIC PERIOD

ALLOSAURUS

ARCHAEOPTERYX

CERATOSAURUS

COMPSOGNATHUS

APATOSAURUS

BRACHIOSAURUS

STEGOSAURUS

THE EARLY CRETACEOUS PERIOD

ACROCANTHOSAURUS

CARCHARODONTOSAURUS

DEINONYCHUS

SPINOSAURUS

SUCHOMIMUS

AMARGASAURUS

HYPSILOPHODON

IGUANODON

OURANOSAURUS

PSITTACOSAURUS

PTERODAUSTRO

BARYONYX

THE LATE CRETACEOUS PERIOD: CARNIVORES

CARNOTAURUS

DEINOSUCHUS

MOSASAUR

PTERANODON

QUETZALCOATLUS

TYRANNOSAURUS

TROODON

VELOCIRAPTOR

MONONYKUS

THE LATE CRETACEOUS PERIOD: HERBIVORES & OMNIVORES

EUOPLOCEPHALUS

LAMBEOSAURUS

MAIASAURA

PACHYCEPHALOSAURUS

PARASAUROLOPHUS

PROTOCERATOPS

STYRACOSAURUS

TRICERATOPS

OVIRAPTOR

NON-AVIAN DINOSAUR FOSSIL SITES MAP

INDEX

Introduction

In popular culture, dinosaurs are often described as big, bad and dangerous to know. When talking about terrestrial creatures, like Brachiosaurus (a plant-muncher that grew up to 25m/82ft long), it’s certainly true that they were big. In an ecosystem where animals must eat to survive, it’s hard to label any creature ‘bad’, but perhaps Velociraptor, with its infamous killer claws, might fit the bill.

Ophthalmosaurus

Triceratops

And while Tyrannosaurus rex would probably top most people’s list of ‘dangerous dinosaurs’, any animal can be dangerous, especially if it weighs a few tonnes! Yet, when writing about dinosaurs it’s hard to avoid superlatives like ‘monstrous’, ‘fearsome’ or ‘deadly’.

Ouranosaurus

Apatosaurus

However, the truth is that there’s more to dinosaurs than big teeth, sharp claws and bone-crunching jaws. These amazing creatures represent a rich tapestry of life that is now long gone, but which we can still occasionally glimpse, thanks to their preserved remains. Sadly, these remains are often just that – ‘remains’: fragments, broken bones, bits and pieces. Because of this, you’ll find, as you flick through this book, the words ‘probably’ and ‘possibly’ on almost every page. Even the seemingly miraculous reconstructions carried out by scientists in the field are limited.

Velociraptor

Euoplocephalus

There’s still much that we don’t know about dinosaurs and their prehistoric neighbours, like the pliosaurs and the pterosaurs. Thankfully, as long as people continue to be fascinated by these brilliant beasts, then the work will continue. And who could fail to be fascinated by real-life ‘monsters’ even if they weren’t really that monstrous!

Postosuchus

Pteranodon

The Triassic Period

If we could travel back in time 248 million years to the end of the Permian Period, we would find an Earth that looked like an alien planet – and which had suffered a major extinction event.

At this time, almost all of the land was concentrated into one, vast super-continent that straddled the equator – Pangaea (‘all earth’). This mass was surrounded by a massive world-ocean – Panthalassa (‘all sea’). Temperatures were hot but with wild seasonal and geographical variations. In the wetter north – as far as the Pole – were lush, primitive ‘woodlands’. In the drier south were forests of impossibly giant ferns. Wildlife varied from region to region too. In the vegetation-rich south, there were huge herds of grazing herbivores. In the north, it was predators that ruled the roost.

However, this was a world in transition. Volcanoes were beginning to tear the land apart. Carbon levels were rising, poisoning the seas. Deserts were replacing the forests. Old species were dying out and new ones were appearing. In fact, the start of the Triassic is marked by a major ‘extinction event’. We don’t know what caused this, but it was so severe that it is known as the ‘Great Dying’. Up to 96 per cent of all marine species died, and this is the only period in the Earth’s history when insects too suffered a mass extinction. Following this ‘die off ’, new species evolved, including the ancestors of many modern mammals, invertebrates and amphibians. Reptiles were still the dominant animals, but change was on the way. The Earth was about to encounter the first proper members of a group that would become infamous. Welcome to the Triassic – the first Period of the Mesozoic Era – the Age of the Dinosaurs.

Cynognathus

248–206 MILLION YEARS AGO

Looking like some strange cross between a wolf and a lizard, Cynognathus belongs to a group of mammal-like reptiles that once dominated the Permian. Those who survived the great Permian-Triassic Extinction were very much a product of their time: both daring and dangerous.

Was Cynognathus a mammal, a reptile, or something in between? Fossils have been found all over the world, suggesting that these agile predators were one of the more successful groups of the Early Triassic. They were also one of the more interesting because they belong to a Class known as ‘synapsids’. This is a group that includes real mammals as well as ‘mammal-like’ reptiles. In fact, it’s easy to imagine Cynognathus as a mammal-reptile hybrid since it has characteristics of both groups.

When viewed from a distance, for instance, it walked with a typically lizard-like ‘sway’. This was because its backbone could move from side-to-side only, not up and down, which is more common in mammals. On closer examination, though, Cynognathus starts to look like a very strange reptile indeed.

Its stance – the way it held its legs, straight beneath its body – would be the first thing that you’d notice as you moved in for a closer look. The legs of reptiles are generally set to the sides of their bodies and held in a ‘bent’ position. Before they can run, they have to straighten out their legs and hoist their bellies off the ground. In contrast, Cynognathus had the sort of sleek body ‘design’ we see in mammalian hunters. Move closer still, and you’d notice fur and partially forward-facing eyes – two traits that gave Cynognathus a distinctly ‘mammal-like’ appearance. However, the most interesting features of Cynognathus wouldn’t be immediately obvious to the casual observer.

The Dino Detectives

Being a palaeontologist is a little like being a detective. Evidence is important, but so is the ability to make deductions from the clues you’ve been given. With good fossils, it can be surprisingly easy to work out what an animal that died 240 million years ago might have looked like. Figuring out exactly how it ‘lived’, though, is considerably trickier!

For instance, Cynognathus had more than one type of teeth (they were ‘differentiated’). This suggests that it would not only have been able to capture a wide range of prey but that it would also chew its food, rather than gulp it down whole, which is how most reptiles eat. Tiny ‘canals’ found in the bones around the snout hint that it had whiskers, similar to modern-day dogs.

Sometimes palaeontologists can even get clues about an animal’s life by looking at what’s ‘missing’ from a fossil. In the case of Cynognathus, fossils show that it had no ribs in the stomach region. In mammals, this area is where a large muscle called the diaphragm (which aids breathing) is located. It therefore seems logical to deduce that Cynognathus had a diaphragm. All these clues – and more – have led some dinosaur detectives to suggest that Cynognathus was more than ‘mammal-like’. They think that this creature was warm-blooded and may even have given birth to live young.

Size isn’t everything. Although stocky herbivores like Kannemeyeria were about twice the size of Cynognathus, they could easily be overwhelmed by a pack of aggressive predators. Working just like modern-day hyenas, these Cynognathus single out a young Kannemeyeria from the herd before moving in for the kill.

Injured and exhausted from its struggle, the beleaguered Kannemeyeria finally collapses. The rest of the pack promptly move in. Using their teeth and claws to tear open their prey’s thick hide, the hungry hunters begin feeding. But speed is essential. The pack must fill their bellies quickly before bigger predators move in to take their share.

Gracilisuchus

248–206MILLION YEARS AGO

Making a living in the Mid-Triassic could be tricky. Luckily, Gracilisuchus was a capable and cunning predator. With a body designed for speed and agility, this little reptile was fast enough to catch and make a meal out of almost anything – from insects to fish.

Everyone loves a good monster story, and you can’t get more monstrous than dinosaurs. So it’s no surprise that in popular culture large, ferocious reptiles are often called dinosaurs even if they aren’t! In fact, what we so often see in films or on TV aren’t even dinsosaurs at all. They’re mosasaurs, plesiosaurs and pterosaurs, just some of the many prehistoric animals which lived – and died – alongside those more famous ‘terrible lizards’.

Even for the scientific community it can be quite difficult to differentiate true dinosaurs from these ‘other animals’. This is why, if you asked an expert to define what they meant by ‘dinosaur’, you would probably get more than one answer! An evolutionary biologist, for example, might say that dinosaurs are the group consisting of ‘Triceratops, neornithes (birds), their most recent common ancestor, and all their descendants’. Other experts might point to specific physical characteristics that all dinosaurs share, such as having legs that are held erect under the body. A simpler, equally valid, definition might be that dinosaurs are land-based ‘archosaurian’ reptiles, which lived from the Late Triassic to the Late Cretaceous Period (about 230-65 million years ago). It’s a complex subject – and becoming increasingly so, especially as new scientific techniques reveal previously unknown facts about these iconic beasts.

One thing is for certain, though: even the experts sometimes get it wrong – as the story of Gracilisuchus certainly proves.

Crocodile Confusion

Gracilisuchus fossils were first discovered in Northern Argentina which, 230 million years ago, was part of the gigantic super-continent Pangaea. Back then, this region was undergoing dramatic change. A warm, wet climate was being replaced by hotter, drier weather. Hardy conifers were beginning to replace the dominant ferns and a new group of animals – the dinosaurs – were starting to emerge. When Gracilisuchus was discovered in the 1970s, it was assumed to be one of these ‘new’ dinosaurs – and it’s easy to see why. After all, it had the same long jaws, sharp teeth, blunt snout and short fore arms as many of the meat-eating theropods of the Late Triassic Period. It even ran on two legs.

It took almost a decade to uncover the real facts about this feisty little predator, although the famous American palaeontologist Alfred Sherwood Romer (1894–1973) suggested the truth back in 1972.

Romer was passionate about evolution and comparative anatomy. His work involved the study of how animals change and evolve physically over time. The knowledge he acquired led Romer to realize that Gracilisuchus wasn’t a dinosaur at all. This was a difficult claim to prove, and he did not have the aid of modern scientific techniques, but we now know that he was correct. Gracilisuchus isn’t a dinosaur, but an early ancestor of the crocodile.

Gracilisuchus may have been a proficient predator, but he was also small and agile enough to make a skilful scavenger – able to literally steal food from under the noses of much larger carnivores.

Fish may also have been on the menu for our intrepid little hunter. But this time, despite his natural speed, he isn’t quite fast enough to make a meal out of this shimmering shoal!

Insects have been around since the Palaeozoic Era (about 540–248 million years ago), when they reached giant proportions. By the Triassic, they were much smaller but they still made good eating for any animal fast enough to catch them.

Coelophysis

248–206 MILLION YEARS AGO

With virtually hollow legs, a streamlined body and powerful hind limbs, Coelophysis was built for just one thing: speed. This made it both a hugely efficient hunter and a superb scavenger – speedy enough to steal food from larger dinosaurs and live to tell the tale!

Imagine the scene: it’s feeding time in the Late Triassic. A group of young Coelophysis are gathered in a lowland clearing. As their mother approaches, they call out excitedly, jostling one another, eager to be the first to eat. With a casual flick of her long neck, she deposits the morning’s catch at the feet of her hungry brood. Although they’re young, the Coelophysis have no trouble tearing open the carcass – using their razor-sharp teeth to rip hunks off the stillwarm flesh. From a little distance away, their mother watches anxiously. Her keen nose has caught the scent of a group of predators nearby. She can’t see them yet, but experience has taught her to be cautious. As her young quickly devour the kill, she remains on the alert, scanning the undergrowth for danger. Her mate has already set off to find more food for their ever-hungry and rapidly growing family.

Then, suddenly, the attack comes. Without warning, a group of rival Coelophysis sprint from the foliage, heading straight for the startled young. One makes a grab at the half-eaten meal as the youngsters flee, but another adult spots more promising prey. With a swift snap of its long jaw, it spins round and grabs one of the young. Their mother howls in distress and launches a counterattack, as the rest of her brood scatter in terror. The youngster struggles, but already it’s too late. The adult’s teeth have inflicted deadly damage. The cannibal Coelophysis has made his kill.

A Bad Rep

The sort of scene just described is one that, until recently, palaeontologists believed could have been commonplace amongst Coelophysis. Surprising though it seems, cannibalism occurs quite frequently in the animal kingdom. Fish, rodents, polar bears and chimpanzees will eat their own young, as well as prey on the young of others of their own species. It seems like a cruel practice, but in survival terms it’s very practical. Often it’s the male who is responsible for the killing, usually dispatching any offspring that his mate has borne for other males. This ensures that his children, not another male’s, survive to reproduce and pass on his genes. Sometimes the reasons are harder to understand, but a range of factors, including hunger and even stress, play their part. Female mice, for instance, are known to kill and eat their young if their nest is threatened.

Many of the best Coelophysis fossils have been found at Ghost Ranch in New Mexico, USA. The large number of remains that have been found in this one place led palaeontologists to suggest that Coelophysis lived in large packs, like modern-day wolves. In fact, the TV series Walking with Dinosaurs showed exactly this type of behaviour. However, just because these Coelophysis died together doesn’t mean that they lived together. The climate in the Triassic Period could be extremely changeable – either very wet or very dry – and it’s now thought that this group died in a flash flood, which washed their remains into the Ghost Ranch graveyard.

When Coelophysis fossils were first examined, a number of adults were found to have in their stomachs what appeared to be the remains of juveniles. The evidence from these fossils seemed clear: Coelophysis was a cannibal. However, the specimens were re-examined in 2002, when it was proved that the half-eaten remains belonged to other reptiles. These included small predators like Hesperosuchus, which resembled the young Coelophysis. So, finally, a 230-million year old story has been given a less gruesome ending – or, at least, one that is slightly less gruesome for the young Coelophysis!

Herrerasaurus

248–206 MILLION YEARS AGO

Herrerasaurus was one of the earliest known species of meat-eating dinosaurs. When these two-legged ‘bipeds’ first appeared in the Late Triassic, around 228 million years ago, slower, four-legged predators were still in the majority. Herrerasaurus was very much the shape of things to come.

Pink, purple or puce – what colour were dinosaurs? Although fragments of skin, fur and feathers have all been found, the pigments that carry colour are organic and are lost during fossilization. It is for this reason that, when you flick through old textbooks, you will see that dinosaurs are always shown as grey. This was because it was considered ‘unscientific’ to add colour without evidence to support it. Luckily, in recent years, it has become more acceptable to speculate what these great beasts may have looked like in ‘living colour’. We can never be 100 per cent certain, of course, but we can make educated guesses by looking at their closest living relatives, as well as by examining their lifestyles and habits.

It’s likely that most dinosaurs had some form of cryptic camouflage’ to help them stay hidden from danger, especially the prey species. Some dinosaurs may have worn ultra-bright ‘warning’ colours – reds, yellows and oranges – to tell others to stay well away. This type of coloration can be seen today in poisonous amphibians and reptiles. Some dinosaurs may have been ‘mimics’, adopting the warning colours of other, more dangerous species to keep themselves safe. Even predators at the very the top of the food chain would probably have been quite colourful. After all, camouflage is very useful when hunting, allowing you to get close enough to prey to strike a killing blow.

Big, Bold and Beautiful!

By looking at the modern-day descendants of dinosaurs – birds – we can also speculate about the wild and wonderful colours that adults may have adopted during the breeding season.

Birds go to elaborate lengths to find a mate. For many, this means abandoning their everyday attire in favour of showy ‘display’ plumage. Red breasts, fancy headgear, multi-coloured tail feathers and patterned ruffs are all worn in the breeding season, and there’s no reason to assume that dinosaurs were any less flamboyant. However, in the case of Herrerasaurus, it may well have been the female rather than the male who was the show-off! Most female songbirds are smaller and drabber than their male counterparts because they need to stay safely hidden when brooding their young. It’s the job of the male to attract a mate, and only the brightest and boldest are successful. Raptors – the predators of the bird world – are the exception to this rule. It’s usually the female who is bigger and showier.

With Herrerasaurus, fossils of two different sizes have been found. Initially, these were believed to belong to different species, but it’s now been suggested that one is the male and one the female. This gives us an insight into what Herrerasaurus’ world might have been like, with large, brightly-coloured females doing most of the hunting and smaller, duller males helping care for the young.

In the animal kingdom, fights amongst males, to establish dominance within the group, are common. Often these combats are highly stylized so that neither male is seriously injured. It’s all about attitude – proving you’re bigger and better than the next guy. Once he’s established his dominance, however, this ‘Alpha Male’ expects certain privileges – mating with the females and getting the largest share of the kill. Pack members who don’t give him the respect he’s due can expect a rough reception. Partly-healed tooth marks have been found on Herrerasaurus skulls, suggesting that headbiting was a common ‘punishment’ for transgressors, just as in modern wolf packs.

Postosuchus

248–206 MILLION YEARS AGO

This huge carnivore was one of the biggest predators of the Late Triassic Period. With sawlike teeth for slashing prey and jaws that were powerful enough to crush bone, Postosuchus would probably have made an easy meal of most animals it encountered.

The Ancient Chinese have been digging up the bones of ‘dragons’ for more than 2000 years, but it was only in 1842 that a scientific name was given to these curious fossil finds. It was the English biologist Sir Richard Owen (1804–1892) who coined the word dinosauria from the Greek words meaning ‘terrible’, ‘fearful’ or ‘wondrous’ (deinos) and ‘lizard’ (sauros). Ever since then, these formidable creatures have captured the imagination of artists, authors and film-makers worldwide.

Although few prehistoric animals were probably very ‘terrible’, in fiction they are usually massive, monstrous, meat-eaters. In fact, beasts just like Postosuchus! So it’s no surprise that it has become something of celebrity in recent years. Thanks to CGI (computer-generated imagery) shows like the BBC’s Walking with Dinosaurs have been able to bring Postosuchus ‘back to life’ – and into our living rooms. (The first show in the series actually featured Postosuchus.) In reality, of course, your living room is last place you’d want to find one of these fearsome archosaurs!

Growing up to 5m (16ft 4in) long, this impressive beast is estimated to have stood around 1.2m (3ft) tall and weighed up to 681kg (1500lb). With its narrow snout, powerful tail and a stocky body, raised up on four, columnar legs, it’s easy to see this ancient reptile as some giant over-sized crocodile. Indeed, because its legs are held straight, directly beneath its body, it was likely to be fast on its feet and is often referred to as the ‘running crocodile’.

A Texan Terror

It was the palaeontologist, Sankar Chatterjee, who first presented Postosuchus to the world in 1985. The name Postosuchus means ‘Post crocodile’, after Post Quarry Texas, USA where much of Chatterjee’s work has been based. (Post Quarry forms part of the well known Cooper Canyon Formation which dates from the Triassic Period.) Since then, Postosuchus fossils have also been found in Arizona’s Petrified Forest and in Durham County, North Carolina, where a new species, Postosuchus alisonae was discovered in 1994.

Just like its crocodile cousins, this rapacious reptile seems to have been a skilled hunter. Its teeth are large and well serrated – perfect for tearing off hunks of flesh. Its jaws are deep and powerful with a flexible enough palate to allow it to swallow large chunks of meat, whole. Add its long, curved claws and fast, powerful body to the equation and there’s no doubt that this Late Triassic predator was a carnivore! It seems to have been an opportunist too, as it is known to have fed on at least four different species. These included the slow, stocky, mammalian dicynodonts, primitive amphibians belonging to the order Temnospondyl and the heavily armoured aetosaurs. Although it is impossible to know for sure, such a diet suggests that Postosuchus lived and hunted on both land and near, if not actually in, water – probably ‘interfluve’ areas of dry land between river systems.

Postosuchus was one of the largest meat-eaters of its age. Only Saurosuchus