9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Hamad Bin Khalifa University Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Josephine comes to Kuwait from the Philippines to work as a maid. She meets Rashid, and with all the wide-eyed naivety of youth, believes she has found true love. But when she becomes pregnant, and with the rumble of the Gulf War growing louder, Rashid abandons her and sends her home with their baby son, José. Brought up struggling with his dual identity in the Philippines, José clings to the hope of returning to his father’s country when he turns eighteen. Will his Kuwaiti family live up to his expectations? Alsanousi crafts a captivating saga that boldly deals with issues of identity and alienation.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

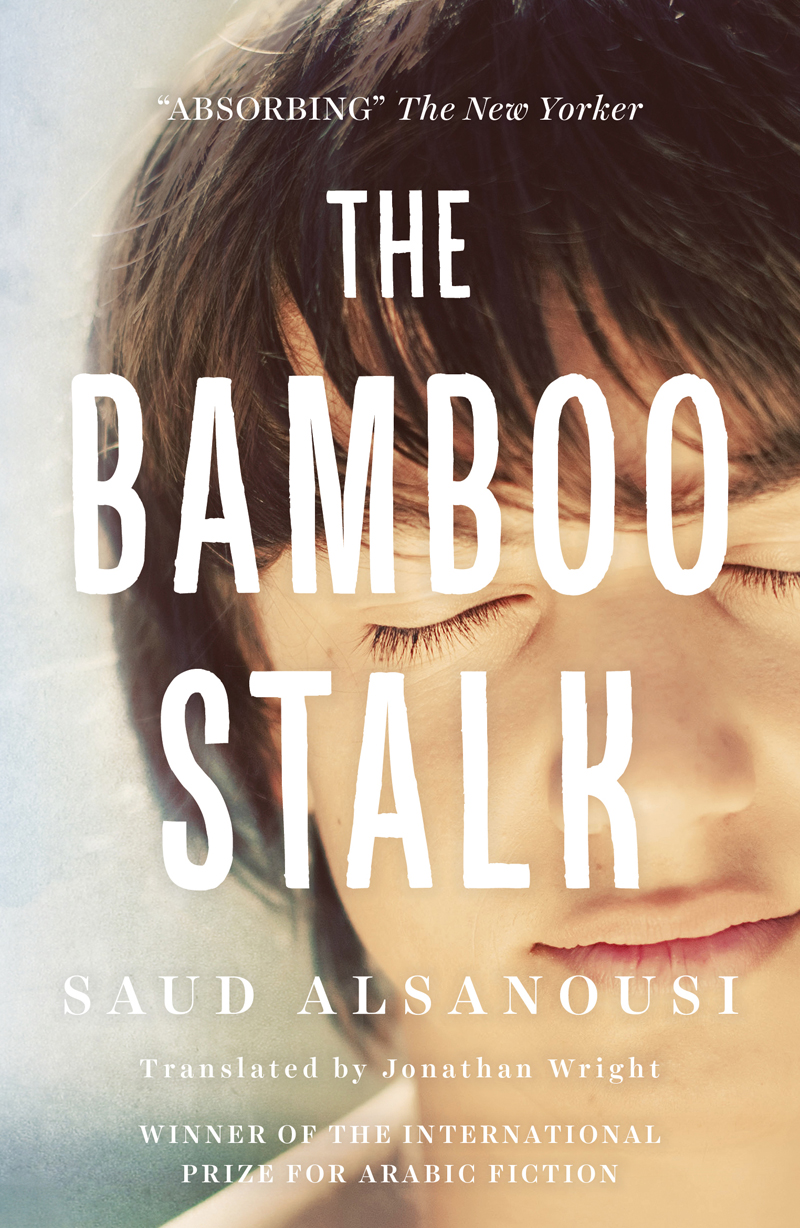

THE BAMBOO STALK

SAUD ALSANOUSI

Translated by Jonathan Wright

Dedicated to crazies who are not like other crazies, crazies who resemble only themselves . . . Mishaal, Turki, Jabir, Abdullah and Mahdi. To them and only them.

Contents

PART 1 Isa . . . Before He Was Born

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

PART 2 Isa . . . After His Birth

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

PART 3 Isa . . . The First Wandering

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

PART 4 Isa . . . The Second Wandering

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

PART 5 Isa . . . On The Margins Of The Country

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

PART 6 Isa . . . Looks Back

The Last Chapter

A Note on the Author

A Note on the Translator

PART 1

Isa . . . Before He Was Born

‘There are no tyrants where there are no slaves.’

José Rizal

1

My name is José. In the Philippines it’s pronounced the English way, with an h sound at the start. In Arabic, rather like in Spanish, it begins with a kh sound. In Portuguese, though it’s written the same way, it opens with a j, as in Joseph. All these versions are completely different from my name here in Kuwait, where I’m known as Isa.

How did that come about? I didn’t chose my name so I wouldn’t know. All I know is that the whole world has agreed to disagree about it.

When I was growing up in the Philippines, my mother didn’t want to call me by the name my father chose when I was born. Although it’s the Arabic equivalent of Jesus and she’s a Christian, it’s still an Arabic name and isa is the Filipino word for the number one. I suppose it would sound funny if people called me a number instead of a name.

My mother called me José after the Philippine national hero José Rizal, who was a doctor and writer in the nineteenth century. Without Rizal the people wouldn’t have risen up to throw out the Spanish occupiers, but the uprising had to wait till after he was executed.

José or Isa, whatever. There’s no great need to talk about my problem with names or how I acquired them, because my problem isn’t really with names but with what lies behind them.

When I was growing up in the Philippines, the neighbours and others who knew me didn’t call me by either of my real names. They had never heard of a country called Kuwait, so they just called me ‘the Arab’. In fact I don’t look anything like an Arab, except that my moustache and beard do grow fast. The image common in the Philippines is that Arabs are hairy, and cruel as well, and the stereotype usually includes a beard of some shape or length.

In Kuwait, on the other hand, the first thing I lost was my nickname ‘the Arab’, along with my other names and titles, though I later acquired a new nickname: ‘the Filipino’.

If only I could have been ‘the Filipino’ in the Philippines, or ‘the Arab’ in Kuwait! If only the word ‘if’ could change things, or if . . . but there’s no need to go into that now.

I wasn’t the only person in the Philippines born to a Kuwaiti father. Plenty of Filipina women have had children by Kuwaiti men, or other Gulf men, and even other Arabs. The women worked as maids in houses in the Arab world or messed around with tourists from Arab countries who came seeking pleasure at a price that only someone in dire need would accept. Some people engage in vice to satisfy their natural urges; others, due to poverty, engage in vice to fill their stomachs. In many cases the outcome is fatherless children.

Many young women in the Philippines are treated like paper handkerchiefs. Strange men blow their noses on them, throw them on the ground and walk away. Those handkerchiefs then give rise to creatures whose fathers are unknown. Sometimes we can tell who the fathers are by the appearance of their children, and some of the children have no qualms about admitting they don’t know who their fathers are. But I had something that set me apart from those whose fathers were unknown: my father had promised my mother that he would take me back to where I was meant to be, to the country that had produced him and to which he belonged, so that I too could belong, and live as all those who shared his nationality lived, in comfort and peace for the rest of my days.

2

My mother, Josephine, went to work in Kuwait in the mid-1980s, in the home of the woman who would later become my grandmother. She abandoned her education and left her family behind. The family was in desperate straits and her father, her sister who had just become a mother, her brother and his wife and their three children were all pinning their hopes on my mother to provide for them. They wanted a life, not necessarily a decent life, but a life.

‘I never imagined I would work as a housemaid,’ my mother would say. She was a girl with dreams. She had ambitions to complete her education and get a respectable job. She wasn’t at all like the rest of her family. While her sister dreamed about buying shoes or a new dress, my mother dreamed about getting hold of books, either by buying them or borrowing them from one of her classmates at school. ‘I read lots of stories, fantasies and ones about real life. I loved Cinderella and Cosette, the heroine of Les Misérables, and I ended up a maid like them but, unlike them, my story didn’t have a happy ending,’ she said.

Circumstances drove my mother to leave her country and family and friends to work abroad. Although it was hard for a woman of twenty, she had a much better life than her sister, Aida, who was three years older. Aida went out to work early because the family was hungry, their mother was ill and their father was a gambler who wasted his money and ran up debts breeding cocks for fighting. So the parents saw no alternative but to offer their elder daughter, who was seventeen at the time, to an ‘agent’ who found her work in the local nightclubs and bars and who insisted on his share of the girl’s body and earnings at the end of every working day.

‘Everything happens for a reason, and for a purpose,’ my mother always said, and whenever I looked for a reason for everything that happened, it was always poverty that raised its ugly head.

The further Aida progressed at work, the deeper she sank into the abyss. She started serving in a bar, prey to the eyes and lewd remarks of drunken men, then in a nightclub, where she was jostled by sweaty bodies and groped by stray hands, and then as a dancer in a strip joint, ogled by hungry eyes. So it continued until she reached the highest rank, and the lowest, in the world of night life.

‘Will they go to hell?’ I asked my mother one day, referring to the prostitutes who came out on the streets as soon as the sun went down, like the crabs that scamper along the sandy beach as soon as the tide goes out. When the sun rises again, the beams of light wash away the sins of the night, and when the tide comes in again it sweeps away the crabs, filling in the holes they have dug in the sand in the water’s absence. ‘I don’t know, but they certainly lead men to hell,’ my mother replied without conviction.

For a time young Aida offered her body to anyone who asked, at a price set by her agent. The price for foreign men was higher than the rate that local men with little money were asked to pay. The price varied according to the time and place. There was a price for the hour and a price for the whole night, a price for services provided in the back rooms at the club and another price for services offered in hotel rooms.

Aida become an object, like anything bought or sold at a price. The price was usually a pittance, rarely prohibitive. The price depended on the kind of service she offered. She worked in silence and in sadness, and grew to hate men and their money. What hurts is not that someone comes cheap. What really hurts is that someone should have a price in the first place.

Aida became the family breadwinner. She would come home towards dawn, clutching her little handbag. Her sick mother and her gambler father awaited the contents of the bag with impatience. Sometimes she would come home late and my mother would worry about her elder sister, while the parents saw her lateness as a good omen because it probably meant she had spent the whole night with one of her clients in some hotel. In that case she would fetch a good price, because obviously the man in the hotel would be a foreigner, who would make a larger contribution to the contents of her handbag. Sometimes she would come home with a swollen lip, a bloodied nose or a dark blue bruise on her jaw. Her parents didn’t even notice. The only thing that interested them about the brute who had hurt their daughter was the money he tossed at her after sating his lust.

Aida plunged into this world. She drank alcohol and smoked marijuana. To her everything was permissible and nothing in life had any value. She got pregnant several times but her pregnancies didn’t last long because she had abortions as soon as she found out. She didn’t want the babies and she was under pressure from her parents, who wanted her to keep her wretched job. Then, at the age of twenty-three, she became pregnant with Merla. She kept the pregnancy a secret from everyone except her younger sister, my mother, because she realised it was the only way out of work she had accepted under duress.

Aida didn’t tell her parents she was pregnant till it was too late, after she was fired from her job. By then an abortion would have been impossible. She told them she wasn’t going back to work. Without her income her mother could no longer afford medical treatment and her health deteriorated. Her father, as ever, was more interested in entering his birds in cockfights.

The family lost one member at the same time as a new member arrived. Just as Merla drew her first breath, my grandmother breathed her last.

Merla looked different. She had the features of a Filipina but she also had a pinkish white complexion, blue eyes and a sharp nose.

By that time my mother was twenty and my grandfather saw her as the perfect alternative source of income for the family, a guarantee of its survival while Aida was out of work bringing up her daughter. Since Pedro, the only son, was always busy looking for work and kept his distance from the affairs of his father and his sisters, the time had come to exploit Josephine.

3

Just as my mother was about to start on the same miserable career as Aida, one of our neighbours came round with a newspaper cutting announcing that an agent in Manila was taking applications from women who wanted to work as domestic servants in the Gulf countries. My mother took the cutting from him as if it were a ‘get out of jail free’ card and she was behind bars and starving. Aunt Aida looked at my mother and the neighbour in silence. My mother was already thinking about the suitcase she would have to buy and the other things she would need for a new life abroad. Her imagination was running riot, though of course she didn’t yet have a job. Before she had time to build up her hopes, the neighbour with the cutting added a cautionary ‘but . . .’ Everyone fell silent for him to finish his sentence. ‘You have to give the agent some money to accept your application,’ he said. He went on to talk about the details and how much money was required. Everyone was stunned when he said how much, because the family couldn’t possibly raise such an amount. Aunt Aida went off to her room and my mother burst into tears from disappointment.

‘Stop crying!’ my grandfather shouted. ‘You know I’ve arranged some work for you here. Live with it.’

The neighbour left and my grandfather lay on his back on the shabby old sofa. My mother sat on the floor lamenting her fate.

My Aunt Aida came out of her room after a while, carrying Merla on her hip and holding an envelope that she handed to her younger sister. ‘My father had started to snore,’ my mother said later, recalling the moment. ‘Aida came up to me and whispered, “This is some money I’d saved for Merla. You can do what you like with it, Josephine.”

‘My father stopped snoring,’ my mother went on. ‘He opened one eye and raised his eyebrow, then sat up like a corpse that had suddenly come back to life. “While the elders sleep, the children whisper secrets!” he said.

‘He lunged towards Aida with his eyes shooting sparks. I was still on the floor. He twisted Aida’s arm in an attempt to wrest the envelope from her hand.

‘‘‘Josephine, take Merla!” she shouted. Merla was about to fall but I caught her and stood in the corner watching Aida push my father, swearing at him as he punched and kicked her. Aida was crazy. Who else would dare do that?

‘I was begging them to stop and Merla was crying in alarm. Despite the pushing and the punching, Aida and my father kept talking.

‘“Aren’t you satisfied with selling me to men and . . .” said Aida.

‘“Shut up,” my father interrupted, pulling her hair and slapping her on the mouth.

‘He pushed her hard against the wall. With her front pressed to the wall, he pulled her head back by the hair.

‘“Merla,” he whispered in her ear with a snarl. I imagined his lips parting to reveal fangs and a forked tongue. “A whore’s daughter, with an unknown father.”

‘Aida couldn’t speak but her eyes were wide open in a silent scream. He continued to hiss at her.

‘“I’ll kill her if she keeps bringing trouble to this house,” he said.

‘“Trouble?” Aida asked, then burst out laughing. She looked like a madwoman, with her clothes torn and her hair dishevelled.’

My mother stopped and looked down, then turned her face towards me. ‘Do I have to tell you all these things, José?’ she asked.

I nodded and urged her to continue, so she went on. ‘I swear my father almost pissed in his pants at the sight of Aida. He took his fingers out of her hair. She moved slowly towards the door leading to the yard outside. My father followed her, and I went after, carrying Merla. Close to the low bamboo fence around the pen where he kept his cocks, under the big banana tree, Aida stopped. I stood behind my father at the back door of the house. “It’s you betting on these cockfights that’s the real trouble,” Aida said, in a voice that was hardly audible.

‘My father didn’t say a word, and Aida continued. “You’re all cockerels!” she said.

‘“It looks like your sister’s gone mad,” my father whispered to me.

‘I didn’t say a word, because she really did look mad.

‘“You’re a cockerel,” Aida said, pointing her finger at my father. “All the men I gave my body to were cockerels,” she added.

‘My father’s face showed a trace of remorse, or maybe fear, but he didn’t move an inch.

‘“Ah, ah, Aida!” he said. All he did was say her name.

‘But Aida didn’t hear him and she continued. “And I’m fed up with playing the role of hen!” she said.

She hitched up her dress above her knees and stepped over the low bamboo fence around the pen. She stood in the middle of the pen, puffed out her chest and looked up to the sky.

“Cockadoodledoo!” she crowed.

‘Then she pounced on the cocks and began to rip their heads off one by one with her bare hands. She threw the four lifeless bodies towards my father, who almost collapsed in a faint. Aida stood upright, facing us, her hands covered in blood. “Next time it’ll be your head,” she said, pointing at our father.

‘The next morning Father left home early with Aida’s envelope. He came back a few hours later carrying a wicker cage with four new cocks inside.’

4

My mother continued her story. ‘Aida and I ran into Father with his cage of birds in the narrow passageway that leads to the lane at the end of the front yard. He didn’t look in our direction. He’d been avoiding looking at Aida since the incident with the cocks. As soon as she came into sight, he looked aside as if he thought she had some eye disease and he was frightened of catching it. Aida had freed herself from slavery and put a stop to my father’s tyranny. I wanted to escape from slavery too, but I’m not Aida. That morning she took me to the grocer’s shop at the end of the lane. The grocer knew us well and had often lent us small sums of money when my mother was alive. Aida told him the whole story. She said I needed money to work abroad as a maid. The man was sympathetic, as he usually was with us, but he said he was sorry he couldn’t provide that amount. As we were about to give up and go home, he said, “I can vouch for you with the Indians. They trust me. I’ve been dealing with them for years.”

‘Dealing with the Indians meant setting in motion an endless cycle of debt. It meant obediently making regular payments to people who took advantage of your poverty and then watching with your own eyes as the money you paid multiplied and went into other people’s pockets.

‘The shopkeeper arranged a meeting between us and one of the Indian moneylenders,’ my mother continued. ‘We knew the Indians because we’d had dealings with them years earlier. We’d bought a cooker and a television and some ceiling fans and floor fans from them on credit. It took us ages to pay back all the money we owed. They were greedy then, but the terms when we bought all those things from them were better than the terms they asked for giving me a loan to go abroad. The shopkeeper tried to explain my circumstances to them, but they still doubled the interest rate. They took advantage of my urgent need for cash.’

My mother shook her head sadly, then continued. ‘We had no choice but to accept. We would have done anything to save ourselves in the short term, even if it meant more trouble down the road.

‘In the employment agency in central Manila the next day I had to stand in a long queue that started at the door to the little office and ran along the pavement, down the street and far into the distance.

‘Hours later I managed to meet the clerk. I paid him half the amount and started to fill in the forms. On my next visit, after my application was accepted, I paid the rest of the money. The clerk told me I would be working in Kuwait, and that was the first time I had ever heard of the country. I cheerfully got ready to leave, though I knew I would have to give half of what I earned abroad to the Indians and the other half to my family. I willingly agreed to let them share out my money between them, in exchange for leaving me free to do what I liked with my body, free to give it to whoever I chose.’

5

When my mother came to work here in Kuwait, she was completely ignorant of the local culture. The people here are not like people in the Philippines. They look different and speak a different language. Even the way they look at each other can have connotations that she wasn’t aware of. The climate in Kuwait is nothing like the climate in the Philippines, except that the sun does shine by day and the moon comes out at night. ‘Even the sun,’ my mother said. ‘At first I doubted it was the same sun that I knew.’

My mother worked in a large house where a widow in her mid-fifties lived with her son and three daughters. The widow, Ghanima, would later become my grandmother. The old lady, as my mother called her, was strict and neurotic most of the time. Although she seemed to be sensible and to have a strong personality, she was also superstitious and firmly believed what she saw in her dreams. She thought that every dream was a message that she couldn’t ignore, however trivial or incomprehensible it might seem. She spent much of her time looking for an explanation for the things she had dreamed and if she was unable to do so herself she would seek out people who interpret dreams. Although the various interpretations she obtained from these people were different, sometimes even contradictory, she believed everything they said and expected the things she dreamed to take place in real life. On top of that, she saw everything that happened, however banal, as a sign that she shouldn’t take lightly. Once, when I was with my mother and my Aunt Aida in the little sitting room in our house in the Philippines, my mother said, ‘I don’t know how that woman could live like that, keeping tabs on everything that happened, every coincidence that came her way. Once she was invited to a wedding with her daughters and they came back only half an hour after leaving home. “That party finished quickly, madam,” I told her.

‘The old lady went straight upstairs without looking at me. Hind, her youngest daughter, took up my question and replied, “The car broke down halfway there.”

‘I thought of all the cars lined up in front of the house. “What about the other cars?” I asked her.

‘“My mother thinks that if the car hadn’t broken down halfway, then at the end of the journey the angel of death would have reaped our souls,” she said, wiping her lipstick off with a handkerchief.

‘“What do you mean?” I asked her in surprise.

‘“My mother thought some disaster was in store for us,” she replied, bending down to take off her shoes.’

It was a vast house my mother was working in, compared with houses in the Philippines. In fact one house in Kuwait is ten or more times bigger than the houses where my mother came from. My mother arrived in Kuwait at a sensitive time. My grandmother thought her arrival was a very bad omen, and it showed on her face whenever she saw my mother. My father had an explanation for that. ‘You came to our house, Josephine, around the same time a bomb went off near the Emir’s motorcade,’ he said. ‘Without divine intervention it would have killed him. So my mother saw your arrival as a sign of bad luck.’

My father was four years older than my mother. My grandmother mistreated her, and so did my father’s sisters, except for the youngest one, who was temperamental. Only my father was always kind and gentle to her and he often disagreed with his mother and his sisters over how they treated my mother.

I was almost ten when my mother started telling me these stories about things that had happened before I was born. She was paving the way for me to leave the Philippines and go back to Kuwait. In the sitting room of our little house she read me some of the letters my father had sent her after we left Kuwait. Before I went back to Kuwait as my father had promised, she told me all the details of her relationship with him. Every now and then she made a special effort to remind me that I belonged to another, better place. When I first started speaking, she taught me some Arabic words, such as greetings, how to count and how to say ‘tea’ and ‘coffee’ and so on. When I was older, she tried her best to give me a good impression of my father, who I couldn’t remember.

I would sit in front of my mother in our house in the Philippines, listening to her as she told me stories about him. Aunt Aida would usually dismiss her stories impatiently. ‘I loved him, and I still do,’ my mother said. ‘I don’t know how or why. Perhaps it was because he was nice to me when everyone else treated me badly. Or perhaps because he was the only person in the old lady’s house who spoke to me, other than to give me orders, or because he was handsome, or because he was a young writer and was well-educated and had dreams of writing his first novel, and I loved reading novels.’

She smiled as she spoke to me and, strangely, she often came close to tears, as if the events in the story had just taken place.

‘He said he was happy with me because, like him, I liked reading. He told me that whenever he was about to start writing his novel, something always came up to distract him. He kept being dragged into the thick of political events in the region. He wrote a weekly article for a newspaper but it was rarely published because of the censors in Kuwait. He was one of the few writers who opposed the Kuwaiti government’s decision to take sides in the Iran-Iraq war. Imagine how crazy your father was! He used to talk to his maid about literature and art and the political affairs of his country, at a time when no one else even spoke to their servants, except to give orders: bring this, wash that, sweep the floor, wipe the table, get the food ready, come here and so on.’

Aunt Aida grumbled and fidgeted in her seat but my mother continued. ‘I washed and swept and mopped all day long, just so at the end of the day, when the women of the house had gone to bed, I’d be free to chat with your father in the study. I tried to keep up with him when he talked about politics, and impress him by showing off my meagre political knowledge. One day I told him how happy I was that Corazon Aquino had won the presidential elections. She was the first woman to rule the Philippines and had restored democratic government after leading the opposition that brought down the dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos.

‘Your father was unusually interested in what I had to say. “So you put a woman in power!” he said. “Five months ago, on 25 February,” I said proudly. Your father burst out laughing, then checked himself in case he woke up his mother and his sisters. “That was the same day we were celebrating our national day,” he said. He paused. Then, tapping his fingertips on the desk and as if speaking to himself, he said, “Which of us is the master of the other?” I didn’t understand what he was driving at. He talked to me about the denial of women’s rights, as he put it, because in his country women don’t have the right to take part in politics. He looked very sad, then he tried to involve me by talking about the Kuwaiti parliament, which had been suspended by the Emir of Kuwait at the time. Although I didn’t much care about what he was saying, I listened to his voice and took great interest in how he felt.’

‘Why was he talking to you about these things, Mama?’ I cut in.

‘Because the people around him dismissed his ideas? Maybe,’ she replied, spontaneously but sceptically. ‘He was an idealist, I thought, and I’m sure everyone else thought so too. His mother gave him special treatment, saying he was the only man in the house. He was quiet and rarely raised his voice. He spent most of his time reading or writing in the study. Those were his main interests, apart from fishing and travelling abroad with Ghassan and Walid, the only friends who came to visit him, either in the study to discuss some book or to talk about literature and art and politics, or in the little diwaniya in the annex if Ghassan had brought his oud along. Ghassan was an artist, a poet, sensitive, although he was also a soldier in the army.

‘At the time the countries in southeast Asia, especially Thailand, were popular destinations for young Kuwaiti men. Your father often spoke to me about going there with his friends. When he was talking about Thailand one day he looked me straight in the eye and said, “You look like a Thai girl.” Did I really look like one, or was he hinting at something else? I wasn’t sure.

‘It was depressing in the old lady’s big house when he went away with Ghassan and Walid. I would count the days till they came back and got together again and made some noise for a change in the house or in the diwaniya.’

My mother suddenly stopped a moment and looked at the floor. ‘I used to watch them in the courtyard from the kitchen window, laughing and getting their gear ready for a fishing trip,’ she said. ‘They’d be gone for hours and I’d wait for your father to come back so that I could put his fish in the freezer and wash the fish smell out of his clothes.’

She turned to me and said, ‘I hope you find friends like Ghassan and Walid, José, if you go back to Kuwait.’

‘Tell me more, Mama. What about Grandma?’

‘The old lady worried about her son and the way he spent his time. She often told him she was worried that either his books would drive him mad or the sea would sweep him away. She often walked in on him in the study and begged him to stop reading and writing and turn his attention to things that would do him good. But he insisted that writing was the only thing he was good at. He loved the sea as well as his library. He adored the smell of fish as much as his mother liked her incense and Arabian perfumes.’

My mother closed her eyes and took a deep breath as if she was smelling something she loved.

‘Your grandmother was always worrying about your father, not just because he was her only son but because he was the only remaining man in the family and only he could pass on the family name. Most of his male ancestors had disappeared long ago. Some of them were sailors who disappeared at sea and others in other ways. Those who survived only had daughters. The old lady said this was because long ago a jealous woman from a humble family had cast a spell so that only the women in the family would survive. Your father didn’t believe in such things, but your grandmother was totally convinced. In those distant days your grandfather and his brother, Shahin, were the only surviving males in the family. Shahin died young before marrying. Isa married your grandmother, Ghanima, late and they had your father, Rashid, and when Rashid’s father died Rashid was the only male left in the family.’

My imagination ran riot: people dying at sea, sailing ships fighting giant waves, a woman casting spells in a dark room, the males dying out one by one because of magic. My mother’s stories made my family sound like characters in some legend.

‘He was the only reason I had the patience to stay in the old lady’s house and put up with the way she mistreated me,’ my mother continued. ‘He offered me words of sympathy at night, when everyone else was asleep. He used to slip his hand into his pocket, pull out banknotes and give them to me – one dinar, or two or three. Then he would leave. I wasn’t interested in the money of course.’

Aunt Aida interrupted her. ‘All men are bastards,’ she said.

My mother and I turned towards her. ‘However much they don’t appear to be,’ she added.

My mother replied with two words: ‘Except Rashid.’

‘One evening in the kitchen, he put his hand on my shoulder and whispered, “Don’t be angry with my mother. She’s an old woman and she doesn’t mean what she says. She’s neurotic, but well-meaning.” I didn’t want him to take his hand away. I forgot all the insults from the old lady. After that I deliberately made her angry every now and then. I’d drop a glass on the kitchen floor and leave the pieces lying around till the next morning, or I’d leave a tap running all night and making noise, or I’d leave a window open on a windy day so that all the dust came in and landed on the floor and the furniture. When the old lady got up in the morning, she would throw a fit. Everyone in the house would wake up to her shouting and calling out “Joza!”, the name she had given me because she thought Josephine was too hard to pronounce. She would curse and yell and swear, and I would just sweep up the pieces of glass from the kitchen floor or spend the whole day dusting and cleaning the place in the hope that when night came it would bring your father’s gentle hand to touch my shoulder.’

She took out a handkerchief and wiped the tears from her eyes. ‘One day he was writing his weekly article in the study,’ she continued, ‘resting his left elbow on the large file that contained a draft of his first novel. I put a cup of coffee down in front of him and said, “I like watching you write, sir.”

‘“Can’t you call me something other than ‘sir’?” he said.

‘I didn’t know what to say. I couldn’t imagine ever calling him Rashid, like his mother and his sisters.’

‘“Isn’t there anything else you like, other than watching me write?” he asked.

‘“Anything else?” I said.

‘He put his pen down, locked his fingers together and rested his chin on his hands. “Something, or maybe someone?” he said.

‘After that I was sure I was in love with him, or almost, although to him I was no more than someone who would listen without objecting whenever he wanted to explain his ideas and beliefs. Since I was certain he hadn’t fallen in love with me and never would, I was content to love him in return for his interest and his sympathy.

‘When I came to work in their house, your father was just getting over a love affair. He had had a relationship with the girl since he was a student. He wanted to marry her but, because of prejudices I know nothing about, the old lady prevented the marriage. So love alone is not enough to bring you together with the girl of your dreams. Before you fall in love, or so I understood from Rashid, you have to choose carefully the woman to fall in love with. You can’t leave anything to chance. Apparently some names bring shame on others, and that’s what happened with Rashid. As soon as his mother heard the girl’s family name she rejected the idea of Rashid marrying the girl. Some time later the girl married another man.

‘The relationship between your father and me continued like this. When the old lady was asleep in the afternoon or at night, and the sisters were busy at university or watching television upstairs, I would take the opportunity to make tea or coffee for Rashid, and spend as much time as possible with him, listening to stories that mattered less to me in themselves than as a reason just to be in his company in his study.’

6

My mother’s intuition was quite right about his remark on how she looked like a Thai girl. My father was hinting at something. He didn’t say it straight out, but there was an insinuation. My mother didn’t tell me all the details, but he must have been clear about what he wanted, because she answered him firmly. ‘Sir, I left my country to get away from things like that,’ she told him. As time passed, his hints became more explicit but my mother stood her ground.

Then one day he said, ‘Shall we get married?’ and she finally relented. She must have been very pleased, because she accepted the marriage, which wasn’t really much of a marriage.

It was the summer of 1987 and my mother had been in Kuwait for about two years. As my mother told me, and as I later experienced for myself, the summers in Kuwait are brutal. Rashid’s family spent the weekends in their beach house on the coast south of Kuwait City. The house is still there and the family gathers there from time to time.

My grandmother and my aunts had gone there with the Indian driver, on the understanding that my father would drive my mother and the cook there and join them. He set off later the same day but he didn’t go straight to the beach house. He stopped the car in front of an old building not far away. He and my mother got out, while the cook stayed in the car.

‘It was old and in bad shape,’ my mother said, talking about the building. ‘Apparently it was housing for foreign workers. There were clothes hanging on lines in the courtyard and in the windows. It didn’t look like a woman had been near the place in years. There were tyres of various sizes piled up in the corners of the courtyard, and abandoned planks of wood, old wardrobes and cupboards covered in dust and thrown aside any old how. There were coils of wire and mattresses that were torn and faded by the sun. Instead of going in through the front door your father took a narrow passageway to the left towards an outer room. There was a man waiting for us there. He looked like an Arab, with a long bushy beard and a dark mark in the middle of his forehead. He was wearing an Arab gown and an Arab headdress but without the black band that Kuwaitis usually wear to hold the headdress in place. The man called in two other men, who apparently lived there. We didn’t stay long. We sat down in front of the man, who started talking with your father in Arabic. He turned to me and asked, “Have you been married before?” I said no. He asked your father something in Arabic and he answered yes. Then he turned back to me and asked, “Do you accept Rashid as your husband?”

‘He wrote out a piece of paper after we agreed. We signed it, Rashid and me. Then the other two men signed it too. Then it was “Congratulations.”

‘On the way back to the car, I was rather sceptical. “Is that all it takes to get married?” I asked.

‘He nodded and said, “It’s simple.”

I was hesitant and I didn’t feel any different towards your father. When we got out of the car he was my master, and when we got back in again, he was still my master. “Are you sure?” I asked again.

He took the piece of paper out of his pocket. “This piece of paper proves it.” He put his hand out, offering me the paper. “You can keep it,” he said. I asked him about the old lady and his sisters. “Everything in good time,” he replied casually. I shut up. I wasn’t convinced we were really man and wife, but because of the way I felt towards your father I accepted it.

‘We got back in the car and drove off to the beach house. The cook didn’t say anything but he was looking at me suspiciously.’

* * *

I doubt my father did what he did because he really wanted to marry my mother. Perhaps he just wanted to have his way with her. Anyway, it was good of him to go through with this strange marriage.

That same night they had a secret rendezvous at a time set by my father. After midnight my grandmother and my aunts went to sleep. When the lights in the house had gone out one by one, my mother slipped out and walked along the beach in the cold sand.

‘Josephine,’ my father whispered. He was launching the boat into the water. ‘Yes, sir,’ she said.

‘You shouldn’t call me that any longer,’ he replied. ‘Come closer,’ he beckoned, ‘so I don’t have to raise my voice and people notice.’

My mother went up to him and stood there while he launched the boat and jumped in.

‘Has everyone gone to bed?’ he asked.

‘Just now. The old lady and the girls have gone to their rooms.’

He put out his hand to her. ‘Come,’ he said.

She was confused. ‘Where to?’ She asked.

He was still holding out one hand to her. With his other hand he pointed out to sea at a red light that was flashing.

‘Near there,’ he said. ‘We won’t be long. An hour, or two hours at the most.’

She looked behind her at the beach house. ‘But, sir, I . . .’

‘If you insist on calling me “sir”, then I, as your master, order you to come with me.’

My mother took a few hesitant steps towards the boat. She left her shoes in the sand and started to wade deeper and deeper into the water. The water rose above her waist. She grabbed my father’s hand and he put his arm around her waist to lift her into the boat.

He pushed off from shore with a long wooden pole, then started the engine as soon as they were out of easy earshot, while my mother sat next to him with her knees folded up against her chest, hiding the contours of her body, which would have shown through her wet clothes.

Then and there, far from shore and close to the flashing red light, as the boat rocked in the calm sea, I made my first journey, leaving my father’s body and settling deep inside my mother.

7

As the months passed my mother’s belly expanded to make room for me as I grew. The rounded bulge stuck out and she couldn’t hide it forever under her loose clothes. She hid it from my father at first. ‘It was a strange marriage,’ my mother said. ‘It didn’t seem real, especially after he had fulfilled his objective. He was still my master, in spite of everything that had happened. So I kept you secretly inside me because I was frightened he might try to make me have an abortion if he found out.’ Like Aunt Aida, she didn’t tell my father she was pregnant till it would have been impossible to have an abortion.

My father didn’t believe it at first. He didn’t know what to do when he realised she was serious. He told her off for keeping quiet about it for so long. ‘That was when I realised that this wasn’t a real marriage,’ she said. He hinted at the idea of an abortion. When he understood it was too late he promised her he would act at the right time. As time passed the changes were obvious – the way she looked and the way she moved, her complexion, her nose, her lips, her swollen fingers and the way she walked. It wasn’t hard to tell, especially as the lady of the house was the father’s mother. One day in the kitchen, in the presence of the Indian cook, Grandmother sprang the question on her. ‘Who did it?’ she asked, expecting my mother to confess that she had slept with the cook. My mother burst into tears, and the cook fell to his knees, kissed Grandmother’s hands and assured her he had never gone anywhere near Josephine.

My father heard his mother shouting in the kitchen. He left the study and headed towards all the noise. My father sent the cook off with a wave of his hand. He turned to his mother and, casually and rebelliously, he said, ‘It’s me.’

There was a heavy silence, then my grandmother said, ‘Yes, you, the man of the house. You’ll deal with that bastard, won’t you?’

She was sure the cook had done it, so my father had to explain. ‘No, it was me who did it, Mother,’ he said.

She clasped her chest with the palm of her hand, as if her heart had sunk and she had to hold it in place. She put her hands over her ears and then over her face. ‘She’ll have to leave,’ she said, in a voice that was hardly audible.

‘I’m not in the habit of going back on what I say or do, and sometimes there’s no going back anyway,’ my father answered coldly.

His mother was about to collapse. Despite appearances, my father was also close to collapse. She took her hands off her face, sat down and pounded the dining table with her fist.

‘You can write stuff like that for your crazy readers, but not for me,’ she shouted.

‘I made a mistake when I made this baby,’ my father replied. ‘But I don’t want to make a bigger mistake by abandoning it.’ My mother said she had never heard him raise his voice so loud, and this was at his mother!

My three aunts had gathered at the kitchen door after hearing all the noise. They didn’t dare come closer.

‘That slut Josephine must leave the country tomorrow,’ Grandmother said.

My mother clasped her hands together in front of her face and wept.

‘Yes, yes, madam, I’ll leave tomorrow,’ she said.

My father silenced her with his hand. ‘She won’t leave as long as she’s carrying a part of me in her womb,’ he said.

His mother stood up straight, her hands resting on the table in front of her. ‘The girl at college, the one who . . . I’ll arrange the engagement, tomorrow if you like,’ she said.

My father shook his head. ‘It’s too late for that, Mother,’ he said.

‘It’s a disaster, a scandal,’ she shouted between sobs.

She pointed at my aunts at the door. ‘Your sisters, you selfish, despicable man. Who’ll marry them after what you’ve done with the maid?’

Rashid had nothing to say in response.

‘Get out of my house, and take that slut with you. Those crazy books have ruined your mind!’

For a whole week, my mother kept asking my father questions about what had happened in the kitchen that day. ‘Why was she pointing at your sisters?’ she asked. ‘She was talking about books. What was she saying? What were you saying when you shouted in your mother’s face?’

‘He acted out the scene for me and translated the conversation so that I could understand. I cried. Your father made me cry many times, José.’

My mother cried that day because my father hadn’t been open with his mother about the marriage. She cried even more because she knew my father hadn’t rebelled against his mother to protect her or because he wanted to stay with her, but rather to protect me, his unborn child. And although he managed to protect me while I was in my mother’s womb, he couldn’t do so when I came out.

If only he had done what his mother wanted.

If only he had kicked my mother in the stomach and I had ended up a small lump of matter swimming in her blood on the kitchen floor.

8

Rashid and Josephine lived together in a small flat, a flat my father could afford on his modest salary. The only regular visitors were Ghassan and Walid, who were witnesses to an official marriage after the couple moved to their new home.

One day when my mother, Aida and I were sitting around talking, my mother took a copy of her official marriage certificate from the briefcase where she kept her papers, which are now in my possession along with my father’s letters. She pointed to the bottom of the certificate, which neither she nor I could read.

‘This is Ghassan’s signature,’ she said.

She moved her finger to the next signature. She said nothing for a while then, sadly, she said, ‘His signature is crazy, much like him.’

I examined the second signature, the one she called crazy. ‘Whose signature is that, Mama?’ I asked.

‘Walid’s,’ she said, smiling and folding up the certificate.

Then she took two pictures out of the briefcase, including one of my father. He was smiling, very thin with a thick moustache and small eyes behind a pair of glasses, wearing a loose white thobe and a white cap on his head like the ones the Muslims wear in old Manila and the Chinese quarter. I don’t know what made my mother think my father was handsome. The second picture was of two young men on a boat. My mother pointed at one of them. He wasn’t looking at the camera because he was busy doing something. ‘That’s Ghassan. He’s fixing the bait to the fish hook,’ my mother said. Then she pointed at the other man, who was looking straight at the camera. ‘That’s Walid,’ she said. The picture caught my attention. He had a childish face, apparently much younger than my father or Ghassan, and he looked cheerful.

‘He was crazy, unlike Rashid and Ghassan,’ my mother said. ‘He loved racing cars and motorcycles.

He was daring, reckless, argumentative. He loved travelling though he had a phobia about planes. When he had to fly he took sleeping pills before take-off and slept like a log. He didn’t wake up till the wheels hit the runway.’

I liked his character, from his picture and from what my mother said about him. I stared at the picture. He was holding a plastic bag in one hand and my mother said it contained chicken guts, which my father liked to use as fish bait. He was wearing dark sunglasses and was holding his nose because of the foul smell coming from the bag.

‘The smell must have been horrible, Mama,’ I said, pulling a face in disgust.

‘Yes, the smell of guts is really nasty, but the smell of fish on Rashid’s clothes . . .’

She left her sentence unfinished, closed her eyes and took a deep breath until her chest expanded. ‘I miss him so much,’ she sighed.

Aunt Aida pointed to the kitchen door and said, ‘In the upper section of the fridge, José, there are ten galunggong fish. Bring two of them.’ Aida stuck a finger up each nostril, then continued in a hushed voice. ‘Let’s put them up your mother’s nose!’ she said.

My mother ignored her and went on talking about herself and my father when they were together.

My father stayed away from his mother’s house while my mother was pregnant. He was stubborn, she said, or pretended not to care, while inside he badly missed the old lady. I was sure he felt remorse, even if he didn’t show it. He didn’t visit her at all during that period, maybe because he was embarrassed. He did try to contact her but his sisters told him she didn’t want to hear his voice and so none of them made any attempt to get in touch with him.

My father was sure that as soon as I came into the world his mother’s attitude would change. He thought she would take me into her arms as soon as she saw him carrying me, as soon as she realised she had now become a grandmother. He had taken a decision to call me Isa after his father if I was a boy, or Ghanima after his mother if I was a girl.

My mother had no regrets about anything in her life, including marrying my father and getting pregnant with me. She believed and still believes in her own private philosophy: ‘Everything happens for a reason and for a purpose.’ The couple lived in isolation until I was born – the moment my father had been counting on. In the maternity hospital on 3 April 1988, the doctor gave my father the news that I had arrived. ‘Your wife has given birth to a baby boy, and they’re both in good health,’ the doctor said.

My father picked me up in his arms and took a long look at my face. ‘Maybe he was looking for just one thing that you two had in common,’ my mother said. For sure, what he saw was a face with elements taken from other faces, but not from his own. My features were a mixture of my mother’s, Aunt Aida’s and my grandfather’s.

As soon as we three – my father and mother and I – were out of hospital, my father drove to his mother’s house. When we arrived my father asked my mother to stay where she was in the car, because his mother might not be able to handle the sight of her just then, whereas her grandson, me that is, might make it possible for her to accept my mother as time passed. My mother waited in the car while my father carried me in to his mother.

My father tried to open the front door but his mother had changed the locks so that he couldn’t come in if he ever thought of coming back. When he rang the bell a new Indian maid opened the door. He spoke with her a while, then pushed the door to go in and disappeared out of sight of my mother. A few minutes later my mother saw a car drive up to my grandmother’s house. She lay low in her seat so that no one would see her. The car stopped at the kerb outside the house and four women got out. One of them rang the bell and the servant opened the door. It didn’t take long. As soon as they disappeared behind the door, the garage door at the side of the house opened and my father appeared, carrying me in his arms and heading for the car in silence.

‘Your father changed after he visited the old lady’s house,’ my mother said with a sad look. ‘He didn’t speak much and he was always thinking about something. He spent more time reading and writing. I tried to persuade him to go out boating several times but he always refused. He said Ghassan and Walid were busy getting ready for a trip abroad. I begged him to go abroad with them but he refused.

‘Two days after you were born, they did go abroad, but if only they hadn’t!