19,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Carcanet Classics

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

A Times Literary Supplement Book of the Year 2020A Review 31 Book of the Year 2020With The Barbarians Arrive Today, Evan Jones has produced the classic English Cavafy for our age. Expertly translated from Modern Greek, this edition presents Cavafy's finest poems, short creative prose and autobiographical writings, offering unique insights into his life's work.Born in Alexandria, Egypt, Constantine Petrou Cavafy (1863-1933) was a minor civil servant who self-published and distributed his poems among friends; he is now regarded as one of the most significant poets of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, an influence on writers across generations and languages. The broad, rich world of the Mediterranean and its complex history are his domain, its days and nights of desire and melancholy, ambition and failure - with art always at the centre of life.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

C. P. CAVAFY

The Barbarians Arrive Today

poems & prose

translated with an afterword by

EVAN JONES

Acknowledgements

Some of these translations have appeared in the following magazines: Antigonish Review, Bolton Review, Eborakon, Manchester Review, New Walk, PN Review, Poetry, Poetry and Audience, Poetry Ireland Review, The Walrus, The Wolf. A small selection of the poems appeared in a pamphlet published in Toronto by Anstruther Press, The Drawing, The Ship, The Afternoon (2018).

I am indebted to Steven Heighton, John McAuliffe, Ian Pople, Michael Schmidt, and Jena Schmitt for their help and ideas with the writing and translating of these poems. And every thank you to Marion and Ioanna, my parents and family, for patience, support and understanding.

CONTENTS

for Jena Schmitt

NOTE

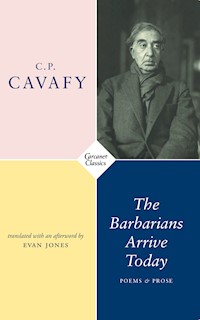

We have been living in Cavafy’s poems since they first began to appear, but translators and editors are always speaking before his poems, filling in all that he chose not to write down. My thoughts on matters of translation and much more are in the afterword. Here, I would like to point out that the photograph on the cover of this book is of Cavafy in 1932. It was taken in Athens sometime between July and October by the photographer Kyriakos Pagonis, about whom I can find little information, in the studio of the modernist sculptor Michalis Tompros (1889–1974). Cavafy had been part of the international committee that commissioned Tompros’s memorial statue of Rupert Brooke on Skyros in 1931. At the time, Pagonis photographed Cavafy from four sides for the creation of a bust that Tompros never completed. The poet was in Athens for treatment of the throat cancer that would take his life the following year. He is wearing a scarf to cover a tracheostomy and could only speak in whispers.

ANCIENT DAYS

THE FUNERAL OF SARPEDON

The deep grief of Zeus – Sarpedon’s life

taken by Patroklus. And now the son of Menoetius

and the Akhaians rush forward to mangle

the body and desecrate it.

But Zeus will not allow that.

This favoured child – abandoned

and lost – Zeus will honour

the dead, this he decrees.

He sends – look! – Phoebos to the plain,

instructed to care for the body.

The dead hero – Phoebos carries him

with reverence and sorrow to the river.

He washes the dust and the blood,

closes the wounds, does not allow

any trace to show; he pours

over him the aroma of ambrosia; dresses

him in pristine Olympian robes.

The skin is cleaned, and the thick, black hair

straightened with a nacred comb.

He lays out and positions the muscular limbs.

He looks like a young king again, a charioteer –

twenty-five, maybe twenty-six –

carefree now that he has won

the first prize in a famous race,

with his golden chariot and swift horses.6

Phoebos comes to the end

of his work and summons Sleep and Death,

the brothers, ordering them

to lay the body in Lykia, land of plenty.

Towards Lykia, this land of plenty,

the brothers, Sleep and Death, walk,

and when they reach

the door of the king’s house

they deliver the treasured body

and return to other cares and chores.

And as soon as the body is received,

the processions, veneration and singing begin,

wine is poured from sacred vessels –

all as it should be on a sad occasion.

And then the craftsmen from the city

and the stone carvers arrive,

ready to shape the memorial and the stele.

August 1908

AKHILLEUS’S HORSES

The horses saw that Patroklus

was dead, the powerful, courageous

youth, and they began to snort;

these immortal creatures grew furious

in full sight of Death’s work.

They tossed their heads, shook their long manes,

struck the earth with their hooves, mourning

Patroklus, seeing him lifeless, collapsed,

his earthly form disgraced, spirit gone,

returned to the great Nothing,

defenseless and breathless.

Zeus turned to see the tears

of the undying horses, heart bursting.

‘At Peleus’s wedding,’ he said, ‘it was rash,

you were presented too eagerly, poor

horses. Why are you wandering

among the arrogant humans – prey to fate?

No death, no aging await you,

only torture by the short-lived, the mistaken.

Humans draw you into suffering.’ This did nothing.

The two noble beasts continued to grieve

for the endless tragedy that is death.

July 1896

PRIAM’S NIGHT MARCH

In Ilium, there is neither calm nor joy.

The land of Troy

cries out in desperation, horror,

bitterly, for Priam’s son, for Hektor.

The lament is unrelenting, heart-breaking.

The all-aching

people of Troy hold in their thoughts

the great man, the tragedy of his loss.

But what’s the point? What good will it bring,

their offering,

in a time of war and violence?

Fate guarantees the wretched man’s silence.

Priam despises any vanity.

From the treasury

he measures gold enough, packs cauldrons,

carpets, wine cups, cloaks and linens,

tunics, tripods, fine attires for women –

he can summon

anything, if a Greek might cherish it.

This is loaded onto his chariot.

He will take the ransom to the enemy

to remedy –

if he can – the terror, so he might recover

his child’s body and undo dishonour. 9

In the calm of night, he sets out.

No doubt,

no worry. There’s just the sound

his chariot makes, crossing the ground.

The bare path extends before him,

light is dim,

a pitiful wind seems to cry and moan,

a dejected raven squawks on its own.

He hears a dog barking out its witness.

The busyness

of a hare on the path is there and gone.

The King drives his horses on.

Shadows unsettle the waking field.

They know to yield,

they sense purpose in the horses’ tramp,

this Dardanid flying towards the camp

of murderous Argives and inhuman

Akhaians.

The King is careless of disaster.

He urges his horses faster, faster.

May 1893 (Hidden)

TROJANS

Our hardships are those of the hapless;

our hardships are those of the Trojans.

We gain a little ground, take some

weight upon ourselves, and begin

to show courage and hope.

But something always stops us.

Akhilleus rises from the trenches

and terrifies all with a great yowl.

Our hardships are those of the Trojans.

We believe boldness and determination

will alter our fortunes,

so we ready for battle.

When the great crisis arrives,

our boldness and resolve are lost,

our spirits rattled, stupefied,

and we scatter around the walls,

seeking somehow to save ourselves.

Our failure is predestined. From the walls,

the songs of sorrow have begun.

They lament the memory, the awareness

of our end. Priam and Hekabe weep for us.

June 1900

WHEN THE SENTRY SAW THE LIGHT

Watching from the House of Atreus, the Sentry

had weathered winters and summers, until finally

he spoke. He saw fires being lit and felt relief –

his hard work was complete.

He had weathered night and day, heat and cold,

looking out over Arachnaion and the old

signal had arrived – it brought happiness,

but less than expected. Only this is

certain: no more waiting, no more anxiousness.

Things are going to change in the House of Atreus.

Any fool can guess the future now the Sentry

has seen the light. Do not worry.

The good light means good men are coming

with their good speeches and good planning.

We pray they will be swift. But Argos

will outlast the House of Atreus.

Houses do not stand forever. Many will speak

and we will listen. But we will not be misled

by the serious and the great and the unique.

Someone serious and great and unique

is always lurking just ahead.

January 1900 (Hidden)

THE INTERVENTION OF THE GODS

Heartily know / … / The gods arrive.

Emerson

Rémonin. – …Il disparaîtra au moment necessaire; les dieux interviendront.

Mme De Rumières. – Comme dans les tragedies antiques?

(Acte II, sc. i)

Mme De Rumières. – Qu’y a-t-il?

Rémonin. – Les Dieux sont arrives.

Alexandre Dumas, Fils,L’Étrangère (Acte V, sc. x)

Now this happens, and then that,

and in year or two the same

happens again in the same way.

Worries better left behind:

we strive to improve our lives.

In striving we fail, muddle things,

walk towards the problem’s cliff

and stand there. The gods must get

to work. They are lowered on cranes

and deliver us, sudden,

violent, plucked up by the waist,

yanked off the stage by a rope.

Their one job, their work completed

for the day, until another steps

forward, moves toward the spotlight,

and there it all starts over.

May 1899 (Hidden)

INTERRUPTION

We interrupt the work of the gods,

we careless, naive, ephemeral beings.

In the palaces of Eleusis and Phthia,

Demeter and Thetis reckon with

great flames and heavy smoke. But

Metaneira always rushes in from the room

of the king, panicked, hair swept back;

Peleus, always afraid, intervenes.

May 1900

FAITHLESSNESS

Thus, although we are admirers of Homer, this we cannot

admire… nor will we praise the verses of Aeschylus

in which Thetis says that Apollo at her wedding:

Was celebrating in song her fair progeny

Whose days were to be long and free from sickness.

And when he had spoken of my lot as in all things blessed

Of heaven, he raised a note of triumph and cheered my soul.

I believed that the word of Phoebus, being divine

and full of prophecy, would never fail. And now

he himself who sang the strain…

...he it is who has slain my son.

– Plato, The Republic 2

Apollo stood up at the marriage

of Thetis and Peleus, during the resplendent

reception feast, and blessed the child the

newly wedded would produce through their union:

May sickness never touch him!

may he live a long life! – This is the way he spoke.

And Thetis was pleased, because the words

of Apollo, which foretell the future,

seemed to ensure the long life of her child.

As Akhilleus grew, and his beauty

was praised throughout Thessaly,

Thetis remembered the words of the god.

But one day old men came with news,

and told of the death of Akhilleus in Troy.

Thetis tore off her purple robes,

removed her bracelets and rings,

threw them all on the ground.

In tears she remembered the old times,

asked what the wise Apollo was doing,

where was the poet who spoke eloquently

at her wedding, where was the prophet

when her son was killed in the prime of life?

And the old men responded that Apollo

himself descended to the plains of Troy

and helped the Trojans kill Akhilleus.

May 1903

SECOND ODYSSEY

Dante, Inferno, Canto XXVI

Tennyson, ‘Ulysses’

The grand second Odyssey,

grander than the first. But

no Homer, no hexameter.

His father’s roof was too small,

his father’s city was too small,

all of Ithaka was too small.

The affection of Telemakhus, the faith

of Penelope, the age of his father,

his old friends, the devoted love

of his people, the pleasant calm of the house

entered the heart of the seafarer

like sunbeams of happiness.

And like the sun they set.

A thirst

for the sea awakened in him.

He despised the overland air.

The apparition of the Evening Star

prevented his sleeping at night.

A nostalgia for travels, mornings

where, arriving in a new port

for the first time, one is happy.

The affection of Telemakhus, the faith

of Penelope, the age of his father,

his old friends, the devoted love

of his people, the peace

and the calm of the house

put him to sleep.

He left.

Once the coast of Ithaka

disappeared from sight, he sailed

towards the West, Iberia,

the Pillars of Herakles –

away from Akhaian waters –

where he felt alive once more,

released from the heavy chains

of everyday domesticity.

And his ambitious heart

delighted in the cool absence of love.

January 1894 (Hidden)

DEMARATOS

The young sophist, Porphyrios, proposed

in conversation the subject, The Character

of Demaratos, which he expressed thus

(he intended to develop the argument):

‘He was prosperous in the court of King

Dareios, and later of King Xerxes,

and now under Xerxes’ command

Demaratos sees himself vindicated.

The shameful injustice done to the son

of Ariston: his foes bribed the oracle,

and were not satisfied when he

forfeited his kingdom.

He relented and agreed

to endure the life of a private citizen,

and they insulted him publicly –

humiliated at a festival.

For these reasons he holds faith in Xerxes.

He will return to Sparta,

the powerful Persian forces beside him,

and so enthroned, he will humiliate

that hypocrite Leotychidas –

he will drive him out.

There come, however, anxieties:

to advise the Persians, to show them

ways to conquer Greece. 19

Detailed, careful planning –

Demaratos has no time for rest.

Detailed, careful planning –

Demaratos has no heart for this:

he feels no happiness

(what he feels is nothing like,

cannot be anything like, happiness),

for he is aware of the outcome:

the Greeks will be victorious.’

November 1911

THERMOPYLAE

May all praise those who in life

guarded Thermopylae.

Never flagging from their errand,

righteous and fair in their actions,

they have compassion for the pitiful,

are generous when rich, and

continue to give when poor;

they are never unhelpful,

always speaking the truth,

withholding hatred for those who lie.

May all praise those men because

they foresaw (as many did foresee)

that an Ephialtes would present himself

and the Medes would get through.

November 1903

HELLENISTIC KINGS

RETURNING FROM GREECE

I see the coast, Hermippes, we’re almost there.

The captain says another day or two.

We’re sailing our home seas.

The currents off Cyprus, Syria, and Egypt,

waters favoured by our countrymen, carry us.

Only silence? Look in your heart:

do you feel happier the farther

we sail from Greece? Are we fooling ourselves?

That would not be very Greek.

The truth is, we are Greeks too –

what else are we? – through the

affections and sensibilities of Asia,

affections and sensibilities

that can surprise the Greeks.

Philosophers, Hermippes, know better

than to behave like minor kings

(we laughed at the royalty

who attended our classes, remember?) –

performing their Greekness,

their Macedonianness (there’s a word!),

where some Arabic feature shows,

something Median they cannot hold back,

and the sheepheaded fools struggle

comically to cover it all up. 24

No, we know better.

Greeks like us avoid the trivial.

The blood of Syria and Egypt

flowing in our veins is not disgraceful:

we should respect it – boast of it.

July 1914 (Hidden)