4,79 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: New Island

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

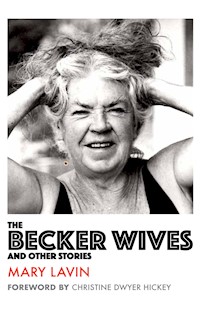

Comprising four long stories – 'The Becker Wives', 'The Joy Ride', 'A Happy Death' and 'Magenta' – this collection is one of Lavin's most celebrated. Together, these stories capture the frustrations and grace of characters struggling to free themselves in places that are often hostile to their desires: a new bride coming home to her husband's prim family, two butlers taking a rare opportunity to go out drinking, a woman pleading with her dying husband to repent, and a young housekeeper whose fortunes seem to have suddenly changed. For the first time in decades, and with a foreword by Christine Dwyer Hickey, the Modern Irish Classics series brings this vital collection to a new generation of readers.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

About the Author

Mary Lavin was born in 1912 in the USA, but moved as a child with her Irish parents to Athenry, Co. Galway, and then to Dublin and her farm in Co. Meath. Lavin wrote two novels, The House in Clewe Street and Mary O’Grady, but is best known for her many short story collections, including Tales from Bective Bridge, The Becker Wives and Other Stories, In the Middle of the Fields, Happiness and Other Stories, and The Stories of Mary Lavin (Volumes I, II and III). She enjoyed an eminent reputation in the land of her birth, where she twice served as writer-in-residence at the University of Connecticut and had many stories published in the prestigious New Yorker magazine. She won the James Tait Black Memorial Prize, two Guggenheim Fellowships, the Katherine Mansfield Prize and the Allied Irish Banks Literary Award. She was also awarded an honorary doctorate from University College Dublin in 1968. Mary Lavin was also a member of Aosdána, Ireland’s state-sponsored affiliation of distinguished creative artists; she was elected Saoi, its highest honour, in 1992 for achieving ‘singular and sustained distinction in literature’. In her private life, she was widowed for fifteen years following the death of her first husband, William Walsh, in 1954, with whom she had three daughters. In 1969, she married the distinguished former Australian Jesuit priest Michael McDonald Scott, who predeceased her in 1990. Mary Lavin died in 1996 and is buried with her family in Navan, Co. Meath.

By the same author

Tales from Bective Bridge

The Long Ago

The House in Clewe Street (novel)

The Becker Wives

At Sallygap and Other Stories (USA)

Mary O’Grady (novel)

A Single Lady

The Patriot Son

A Likely Story

Selected Stories (USA)

The Great Wave (USA)

The Stories of Mary Lavin (Volumes I, II & III)

Collected Stories (USA)

In the Middle of the Fields

Happiness

The Second Best Children in the World

A Memory

The Shrine and Other Stories

Selected Stories (UK)

A Family Likeness

In a Café

The Becker Wives

and Other Stories

The Becker Wives

and Other Stories

Mary Lavin

Foreword by Christine Dwyer Hickey

MODERN IRISH CLASSIC

The Becker Wives and Other Stories

First published in 1946 by Michael Joseph

This edition published in 2018 by

New Island Books

16 Priory Hall Office Park

Stillorgan

County Dublin

Republic of Ireland

www.newisland.ie

Copyright © Mary Lavin, 1967

Foreword © Christine Dwyer Hickey, 2018

The right of Mary Lavin to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright and Related Rights Act, 2000.

Print ISBN: 978-1-84840-694-0

Epub ISBN: 978-1-84840-695-7

Mobi ISBN: 978-1-84840-696-4

All rights reserved. The material in this publication is protected by copyright law. Except as may be permitted by law, no part of the material may be reproduced (including by storage in a retrieval system) or transmitted in any form or by any means; adapted; rented or lent without the written permission of the copyright owner.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

New Island received financial assistance from The Arts Council (An Chomhairle Ealaíon), 70 Merrion Square, Dublin 2, Ireland.

Comhairle Chontae na Mí/Meath County Council has given financial support to this republication.

Contents

Foreword by Christine Dwyer Hickey

The Becker Wives

The Joy-Ride

A Happy Death

Magenta

Foreword

by Christine Dwyer Hickey

Patrick Kavanagh claimed that a would-be writer is best nurtured in an environment of domestic disharmony. If this is the case then Mary Lavin was certainly off to a fine start. She was born in East Walpole, Massachusetts in 1912 to Irish parents who were far from compatible. Her mother, the daughter of a small-town merchant in County Galway, had notions above her station and remained throughout her life a woman disappointed with her lot. Her father, on the other hand, who had come from peasant stock, was self-made and, like many racing men, socialised easily with people from all walks of life.

Like James Joyce before her, also a child of a difficult marriage and a victim of a peripatetic, if – it has to be said – far less comfortable lifestyle, the young Lavin had to adapt to a succession of different surroundings. Each move brought about a new set of people to deal with and a new set of rules to follow. Leaving her father behind, she moved from small-town America to small-town Galway when she was nine years old to live with her mother’s people. A year or so later, she moved with her mother to a house in Dublin. Her father, meanwhile, came back to Ireland where he bought a country estate in County Meath on behalf of his wealthy American employers. There he came to live and work as estate manager with Mary spending weekends and holidays in his company. It was divorce Irish style in the twentieth century and Mary soon learned how to divide herself both physically and emotionally between these two very different forces of nature. For a child this lifestyle can cause damage, particularly in the case of an only child, but, from a writer’s point of view at least, it would do her no harm. Her observational skills were sharpened, her sense of place developed and most importantly of all, she acquired the ability to switch on her imagination whenever an alternative narrative was required.

Lavin described herself as a great wanderer when she was a child. She often wandered alone. In East Walpole, her solitary rambles brought about a life-long love of nature. In Athenry in County Galway, she roamed the town while other children were at school. She was known there as ‘The Yank’ and, as something of a novelty, was often invited into people’s homes to be quizzed by nosy neighbours about her absent father. Little did these neighbours know that the young Lavin was taking in far more than she was giving away: their rooms and furniture; the food they ate, and the ways in which they betrayed themselves not just through their words but through their silences.

In Dublin she would wander again, a convent schoolgirl, straying from the leafy enclaves of respectable Adelaide Road into the less privileged areas of the city. If Athenry had shown her something of the poverty of the spirit; Dublin’s inner city would show her poverty of an entirely different calibre. In any case, it was all going in: landscape, cityscape, the savagery of small-town respectability; the debilitation brought about by the disappointed life. And it would all come out later and flow like an underground river through her work.

My first reading of Lavin was as a child when I came across ‘The Widow’s Son’ in an older cousin’s school textbook. I was drawn in by the simplicity of the writing but if I entered that story expecting a country fable, I was in for a shock. The image of the widow beating her son with the dead body of a bloody hen would, for a long time, haunt me. It was the first time I had read a story that stayed with me beyond the page. It also taught me something about life, consequence and chance, and caused me to wonder if those who are in control of our lives are always in the right.

I mark ‘The Widow’s Son’ as my first experience of adult reading and when New Island brought out the The Long Gaze Back anthology in 2015 (ed Sinead Gleeson), I was delighted to find myself in the same book as Mary Lavin. In the way that one good thing can lead to another, it was the impending reissue by New Island of Mary Lavin’s In the Middle of the Fields collection that led to the inclusion of its title story in The Long Gaze Back and this followed the reissue in 2011 of Happiness and Other Stories also by New Island.

And now we have this collection, The Becker Wives and Other Stories, first published in 1946 by Michael Joseph, reissued here by New Island – and so the renaissance of Mary Lavin continues.

There are only four stories in this collection, which is a little unusual. Two of these stories, however, ‘The Becker Wives’ and ‘A Happy Death’, could be classified as novellas and in length anyhow they certainly qualify as such. My own feeling is that both stories are so intensely concentrated on the emotional lives of their characters that they read more like long short stories.

It’s a balanced selection – the two longer stories are heavily populated; the other two are not. One story concerns the struggles of a well-to-do family; another deals with a family struggling against poverty, or rather against the shame associated with poverty.

‘Magenta’ and ‘The Joy-Ride’ are about people who live in the shadow of larger lives: servants and caretakers trapped by circumstances and the whim of the absent landlord.

‘The Joy-Ride’ and ‘The Becker Wives’ are both humorous stories although the humour becomes darker as the stories proceed. Even so, they contain more comedy than one has come to expect from Lavin’s work, particularly her later work which, despite moments of humour and no shortage of irony, often comes back to grief. But then she was no stranger to grief. In her lifetime she lost two husbands, both of whom she dearly loved and the year before The Becker Wives was published, her adored father died leaving her with, some might say, the wrong parent to contend with for another twenty years.

‘The Becker Wives’ story starts out as a comedy of manners: sleek, sophisticated and fast paced. We are told it is set in Cork although unusually for Lavin, the location of this particular story never really feels specific. In fact, we could just as easily be in small-town America. There is a cinematic texture throughout reminiscent of one of the old Hollywood movie greats such as Harvey or Arsenic and OldLace and even the names of some of the characters, Theobald, Honoria, Henrietta – and these may well be old Cork names – sound more like small-town America, to my mind anyhow. It’s a story that starts out in a satirical vein, poking fun at the middle classes at work and at play, the desire for social success, the insecurity of those who have married above themselves and the in-house snobbery directed against them. However, what starts out as a comedy of manners gradually darkens into a story about mental illness – a subject that arises to varying degrees in three of the stories in this collection.

‘The Joy-Ride’ also starts out as a comedy of sorts. Two butlers, caretakers of a house with no master in residence, decide, in the absence of the overseer, to skip off for the day. The butlers, one middle-aged and cautious, the other young and snide, goad each other into taking more and more risks as they embark on their great adventure. In this story, there can be no doubt as to the location: we are back in a Lavin landscape as, with painterly precision, she lays down the countryside of County Meath. The story is a terrific and often hilarious study of male pride. It clips along before delivering us to a dark and twisted ending.

The third story, ‘A Happy Death’, like many of Lavin’s stories is one of love and hatred combined. Love and hatred locked into a cage in a fight to the death. In a way, this is also a story about decay: the slow decay of a marriage; the decay of the spirit within the family too, as the children become, in the all-consuming unhappiness of their parents’ marriage, superfluous to requirements.

As in many of her stories, the house in ‘A Happy Death’ is seen almost as a character. It seems to mirror the experience of the people living within – in this case, decaying and disintegrating alongside Ella and Robert – a couple who were once deeply in love. In a way love remains, although now it is an overpowering and destructive love, the sort that can only turn in on itself.

Finally there is ‘Magenta’. There is something joyful about this story for all its unhappy elements. The young and slightly wild Magenta, daughter of the local herdsman, is full of optimism despite her lowly circumstances. She comes to do the heavier housework in the local big house – again a house without an owner and one that has seen better days. Two elderly maids are the caretakers and have lived there so long that they feel, and often behave, as if they own it. Like Flora in ‘The Becker Wives’, Magenta breezes in and out of their lives and like Flora, she will pay the price for her joie de vivre.

Mary Lavin was thirty-four when The Becker Wives was first published. She already had three books to her name and would go on to publish several more collections, two novels, and countless individual stories in anthologies and magazines such as TheNew Yorker where she had a first-read contract for several years. She was often labelled as a writer who dealt with the female aspect of life, an examiner of all things feminine – if not quite a feminist writer. But she is not a writer to be closed into any bracket. As we can see in this collection, she was capable of peeling the skin off any heart, male or female, and subjecting it to forensic inspection. She wrote without gimmickry or regard for passing fads. She worked on instinct and, through her own creative impulse, used her life experience to enrich her stories. She pulled the world into herself, turned it around and then gave it an outer expression that is utterly unique. In other words, she was a true artist.

A photograph taken in a garden, in or around 1914 and reproduced in Leah Levenson’s biography The Four Seasons of Mary Lavin, shows a child aged eighteen months, seated in the corner of a basket chair. The expression is amused, inquisitive, discerning; it radiates intellectual acuity. Of course, all children are observers at this age – it’s how we learn to negotiate the world – but it is hard to believe that the child in this photograph is the average toddler. What is easy to believe, however, is that here is someone recording and more importantly, retaining all that she sees and hears. It’s as if there is a camera inside her little head. The fact that the child is alone on the seat, adds to this sense of destiny.

Christine Dwyer Hickey

The Becker Wives

When Ernest, the third of the Beckers to marry, chose a girl with no more to recommend her than the normal attributes of health, respectability and certain superficial good looks, the other two – James and Henrietta – felt they could at last ignore Theobald and his nonsense. Theobald had been a bit young to proffer advice to them, but Ernest had had the full benefit of their youngest brother’s counsel and warnings. Yet Ernest had gone his own way too: Julia, the new bride, was no more remarkable than James’s wife Charlotte. Both had had to earn their living while in the single state, and neither had brought anything into the family by way of dowry beyond the small amount they had put aside in a savings bank during the period of their engagements, engagements that in both cases had been long enough for the Beckers to ascertain all particulars that could possibly be expected to have a bearing on their suitability for marriage and child-bearing.

‘And those, mind you, are the things that count,’ James said to Samuel, now the only unmarried Becker – except Theobald. ‘Of course every man is entitled to make his own choice,’ he added with a touch of patronage, because no matter how Theobald might lump the two wives together, the fact remained that Ernest had taken Julia from behind the counter of the shop where he bought his morning paper, whereas his Charlotte had been a stenographer in the firm of Croker and Croker, a firm that might justifiably consider itself a serious rival to the firm of Becker and Becker. But Theobald ignored such niceties of classification. In his eyes both of his brothers’ wives came from the wrong side of the river, as he put it, and neither of them differed much – in anything but their sex – from Robert, the husband of Henrietta. Robert had been just a lading-clerk whom James had met in the course of business, but since it had never been certain that Henrietta would secure a husband of any kind, the rest of the family – except Theobald of course – thought she’d done right to jump at him. Theobald had even expected her to make a good marriage. But once Robert had been raised from the status of a clerk to that of husband, it had been a relatively small matter to absorb him into the Becker business.

The Beckers were corn merchants. They carried on their trade in a moderate-sized premise on the quays, and they lived on the premise. But if anyone were foolish enough to entertain doubts about the scale and importance of the business conducted on the ground floor, he had only to be given a glimpse of the comfort and luxury of the upper storeys, to be disabused of his error. The Beckers believed in the solid comforts, and the business paid for them amply.

Old Bartholomew Becker, father of the present members of the firm, had built up a sizeable trade by the good old principles of constant application and prudent transaction. Then, having made room in the firm for each of his three older sons, one after another, and having put his youngest son Theobald into the Law to ensure that the family interests would be fully safeguarded, the old man took to his big brass-bound bed – a bed solemnified by a canopy of red velvet, and made easy of ascent by a tier of mahogany steps clipped to the side rail – and died. He died at exactly the moment most opportune for the business to be brought abreast of the times by a little judicious innovation.

In his last moments, old Bartholomew had gathered his sons around him in the high-ceilinged bedroom in which he had begot them, and ordering them to prop him upright, had given them one final injunction: to marry, and try to see that their sister married too.

The unmarried state had been abhorrent to old Bartholomew. He had held it to be not only dangerous to a man’s soul, but destructive to his business as well. In short, to old Bartholomew, marriage represented safety and security. To his own early marriage with Anna, the daughter of his head salesman, he attributed the greater part of his success. He had married Anna when he was twenty-two and she was eighteen. And the dowry she brought with her was Content. By centring her young husband’s desires within the four walls of the house on the quayside, Anna had contributed more than she knew to the success of the firm. For, when other young men of that day, associates and rivals, were out till all hours in pursuit of pleasure and the satisfaction of their desires, Bartholomew Becker was to be found in his countinghouse, working at his ledgers, secure in the knowledge that the object of his desires was tucked away upstairs in their great brass bed. And as the years went on, the thought of his big soft Anna more often than not heavy with child, sitting up pretending to read, but in reality yawning and listening for his step on the stairs, had in it just the right blend of desire and promise of fulfilment that enabled him to keep at the ledgers and not go up to her until he’d got through them. In this way he made more and more money for her. Anna might not take credit for every penny Bartholomew made, but she was undoubtedly responsible for those extra pence, earned while other men slept or revelled, that made all the difference between a firm like Beckers and other firms in the same trade. It was inevitable, of course, that the more money Anna inspired her husband to amass, the more her beauty became smothered in the luxury with which he surrounded her. Yet, on his death-bed, his memory being more accurate than his eyesight, it was of Anna’s young beauty that he spoke. And reminding her of their own happiness, he laid on her a last injunction to be good to his sons’ wives. He made no mention of how she should conduct herself towards a son-in-law, no doubt fearing it unlikely such a person would put in an appearance. Anna gave the dying man an unconditional promise.

Theobald therefore had his mother to contend with as well as his brothers when he objected to each of his sisters-in-law as they came on the scene.

‘Have you forgotten your father’s last words, Theobald?’ Anna pleaded, each time. ‘How can you take this absurd attitude? What is to be said against this marriage?’

‘What is to be said in its favour?’ Theobald snapped back.

And on the occasion of Ernest’s engagement, when Theobald had put this infuriating question for the third time, his mother had been goaded into giving him an almost unseemly answer.

‘After all,’ she said, ‘the same could have been said about your father’s marriage to me!’

That, of course, was the whole point of Theobald’s argument, although he could not very well say so to Anna. Surely he and his brothers ought to do better than their father: to go a step further, as it were, not stay in the same rut. It was one thing for old Bartholomew, at the outset of his career, to give himself the comfort of marrying a girl of his own class, but it was another thing altogether for his sons, whom he had established securely on the road towards success, to turn around and marry wives who were no better than their mother.

‘No better than Mother!’ Henrietta was outraged. She could hardly credit her ears. She had the highest regard for Charlotte and Julia, but a sister-in-law was a sister-in-law, and the implication that either of them could be put on the same plane as her mother was unthinkable. ‘No better than Mother!’ she repeated, her voice shrill with vexation. ‘As if they could be compared with her for one moment. I’m shocked that you could be so disrespectful, Theobald.’

But Theobald was always twisting people’s words.

‘So you do agree with me, Henrietta?’ he said.

‘I do not,’ Henrietta shouted, ‘but you know very well that both James and Ernest would be the first to admit that no matter how nice Charlotte and Julia are they could never hold a candle to Mother. They’ve said as much, many many times, and you’ve heard them.’

It was true.

On his wedding day James had stood up, and putting his arm around his bride’s waist and causing her to blush furiously, he had addressed his family and friends.

‘If Charlotte is half as good a wife as Mother, I’ll be a fortunate man,’ he said.

And Ernest, on his wedding day, had said exactly the same, giving James a chance to reiterate his sentiments.

‘My very words,’ James said, and all three wives, Anna, and the two young ones, Charlotte and Julia, had reddened, and all three together in chorus had disclaimed the compliment, although old Anna had chuckled and nodded her head towards the big ormolu sideboard, laden with bottles of wine and spirits and great glittering magnums of champagne, from the excellent cellar laid down by old Bartholomew.

‘I never heed compliments paid to me at a wedding,’ old Anna said. They all could see though that she was pleased and happy. But just then, happening to catch a glimpse of her youngest son between the red carnations and fronds of maidenhair fern that sprayed out from the silver-bracketed epergne in the centre of the bridal table, Anna leant back in her chair, and lowered her voice for a word with James who was passing behind her with a bottle of Veuve Cliquot that he didn’t care to trust to any hands but his own. ‘For goodness’ sake, fill up Theobald’s glass,’ she said. ‘It makes me nervous just to look at him, sitting there with that face on!’

For Theobald sat sober and glum between Henrietta and Samuel, where he had stubbornly placed himself, thereby entirely altering the arrangement of the table, and causing the bride’s elder sister and her maiden aunt to be seated side by side. Theobald had flatly refused to sit between them, and it had been considered unwise to press the matter.

‘I would have made him sit where he was told,’ Charlotte said to James, when he came back to her side after pouring the champagne and she had ascertained what Anna had whispered to him. ‘Theobald is odd, but he’d hardly be impolite to strangers.’

‘I don’t know about that,’ James said morosely. ‘Don’t forget the way he behaved at our wedding. He wasn’t very polite to – ‘ James stopped short. He’d been about to say ‘your people’ but he altered the words quickly to ‘our guests’.

‘Oh, that was different,’ Charlotte said. ‘That was the first wedding in the family.’

James wasn’t listening though. He was trying to read the expression on Theobald’s face as, just then, his youngest brother turned and spoke to Henrietta. Henrietta frowned. What was the confounded fellow saying now?

It was just as well James could not hear. Theobald was on his hobby-horse. ‘The joke of it is, Henrietta,’ he said, ‘that for all their protestations to the contrary, both James and Ernest would get the shock of their lives if anyone saw the smallest similarity between their wives and our dear mother.’

‘Well, there are differences of appearance, of course,’ Henrietta said crisply. ‘No one denies that.’ She always felt that in every criticism of her sister-in-law there was an implied criticism of Robert, and she was annoyed, but on this occasion she was ill at ease as well in case Theobald would be overheard. He hadn’t taken the trouble to lower his voice.

‘My dear Henrietta,’ he exclaimed. ‘You would hardly expect our brothers’ wives to wear spectacles and elastic stockings on their wedding day and take size forty-eight corsets, would you? Give them a little time. For my own part I’d like to think my wife would have something more to depend upon for attraction than slim ankles and a narrow waist.’

Yet, even Theobald could hardly have foreseen the rapidity with which his sisters-in-law lost their youthful figures. The punctual pregnancy of Julia coinciding with the somewhat delayed pregnancy of Charlotte made both women look prematurely heavy, and there was something about their figures that made it seem they would never again snap back to their original shape. Indeed, since both of them thought it advisable to conceal their condition under massive fur coats, soon there wasn’t a great deal – unless you were at close quarters – to distinguish one from the other of the three Becker wives.

After their confinements, of course, Charlotte and Julia regained some of their differentiating qualities, but even then, due to having followed the advice of Anna and adopted such old-fashioned maxims as ‘eating for two’ and putting up their feet at every possible chance, neither their ankles nor their waists would ever be slender again. Now, too, Charlotte and Julia felt entitled to accept freely the fur capes, fur tippets, and fleece-lined boots that they had been a bit diffident of demanding when they were dowerless brides. Indeed as the years went on, they came to regard these things more in relation to the effect they made upon each other than to the effect upon their own figures, so that when finally Anna passed to her last reward, and the fallals and fripperies she had won in happy conjugal contest with Bartholomew were dispersed among her three daughters, it seemed at times that instead of passing from the scene Anna had been but divided in three, to dwell with her sons anew. And nowhere was their resemblance to Anna as noticeable as when, in accordance with a custom first started by Bartholomew, and strictly kept up by James, the Beckers went out for an evening meal in a good restaurant. But whereas formerly Anna had sat at the head of the table, comfortable and heavy in furs and jewellery, there were now three replicas of her seated on three sides of the table.

Henrietta, Charlotte, and Julia. There they sat, all three of them, all fat, heavy, and furred, yet like Anna, all emanating, in spite of the money lavished on them, such an air of ordinariness and mediocrity that Theobald, when duty compelled him to be of the party, squirmed in his seat all the time, and rolled bread into pellets from nervousness and embarrassment. Yet he had to attend these family functions. One had to put a face on things, as he explained to Samuel, who came nearest to sharing his views. After all, although it was for the benefit of the family that old Bartholomew had made a lawyer out of his youngest son, Theobald was not without a return of benefit. His practice was mainly dependent on family connections and he just couldn’t afford to ignore family ceremonial. But it went against the grain. Indeed, ever since he was a mere youth of sixteen or seventeen Theobald had nurtured strange notions of pride and ambition, and when to these had been added intellectual snobbery and professional stuffiness, it became a positive ordeal for him to have to endure the Becker parties. In Anna’s time, a small spark of filial devotion had made them bearable. Without her it was all he could do to force himself to go through with them. But once at the party, however, he could at least make an effort to keep control of the situations that sometimes arose. With a little tact it was possible to gloss over the limitations of the others.

‘Not there, Henrietta!’ Just in time he’d put his hand under his sister’s elbow and shepherd them all to a quiet corner of the restaurant, whereas left to themselves they would have made straight for a table in the centre of the room. ‘How about over there?’ he’d murmur, and guide them towards a table in a corner behind a pillar, or a pot of ferns.

It was not that he was ashamed of them. There was nothing of which to be ashamed. Indeed, the Beckers were the most respectably dressed people in the restaurant, and they were certainly better mannered than most. Moreover, one and all they possessed robust palates that almost made up for their hit-and-miss pronunciation of the items on the menu. And James, who as the eldest was always the official host, was more than liberal with tips to the waiters. Nevertheless, Theobald was ill at ease and cordially detested every minute of the meal.

‘Are you suffering from nerves, Theobald?’ Henrietta asked one evening, frowning at the disgusting pellets of bread all round his plate. She was the one who was most piqued at being led to an out-of-the-way table. ‘I don’t know why you had us sit here. The table isn’t large enough in the first place, and in the second place we can hardly hear ourselves thinking, we’re so near the orchestra.’

The table was in a rather dark corner, behind a potted palm, and it was indeed so near the orchestra that James had to point out with his finger the various choices from the menu, in order to come to an understanding with the waiter.

‘I wanted to sit over there,’ Henrietta said, indicating an undoubtedly larger and better placed table, but just then the orchestra reached a lightly scored passage, and overhearing his sister, James looked up from the menu.

‘Would you like to change tables, Henrietta?’ he asked. ‘It’s not too late yet: I haven’t given the order.’

Theobald shrank back into his chair at the mere thought of the fuss that would accompany the move. Charlotte and Julia were already gathering up their wraps and their handbags and scraping back their chairs. His left eye had begun to twitch, and the back of his neck had begun to redden uncomfortably.

‘Aren’t we all right here?’ he cried. ‘Why should we make ourselves conspicuous?’ In spite of herself, Henrietta felt sorry for him.

‘Oh, we may as well stay here, James,’ she said, settling back into her chair again and throwing her fur stole over the arm of it. ‘We can’t satisfy everyone, although I must say I don’t know what Theobald is talking about when he says we’d make ourselves noticeable, because I for one can’t see that anyone is taking the least notice of us!’

There was a thin, high note of irritability in his sister’s voice that made Theobald more embarrassed than ever. Under the table he crossed and uncrossed his long legs, and took out his handkerchief twice in the course of one minute, as he tried in vain to disassociate himself from them all. The paradox of his sister’s words suddenly came home to him. She’d put her finger on what was wrong with them. His discomfort came precisely from the fact that there was no one looking at them. They were the only people in the whole restaurant who were totally inconspicuous. Around them, at every other table, he saw people who were in one way or another distinguished. And those whom he did not recognise looked interesting, too. The women stood out partly because of their appearance, but mostly because of their manner which was in all cases imperious. The men were distinguished by some quality, which although a bit obscure to Theobald, made itself strongly felt by the waiters and where the Beckers often had a wait of ten or even twenty minutes between courses, these men had only to click their fingers to have every waiter in the room at their beck and call. As well as that, most people seemed to know each other. They were constantly calling across to each other, and exchanging gossip from table to table.

Yes, it was true for Henrietta. No one was taking the slightest notice of the Beckers. In that noisy, unself-conscious gathering, the Beckers were conspicuous only by being so very inconspicuous. It was mainly because they liked to stare at other people that the Beckers went out to dinner. Theobald looked around the table at the womenfolk, at his family. There they sat, stolid and silent, their mouths moving as they chewed their food, but their eyes immobile as they stared at someone or other who had caught their fancy at another table. There was little or no conversation among them, such as there was being confined to supply each other’s wants in matters of sauces or condiments.

As for the men, Theobald looked at his brothers. They too were unable to keep their eyes upon their own plates, and following the gaze of their wives, their gaze too wandered over the other diners. They had a little more to say to each other than their women, but the flow of their conversation was impeded by having to converse with each other across the intervening bulks of their wives.

Theobald bit his lip in vexation and began to drink his soup with abandon. He felt more critical of them than usual. Was it for this they had dragged him out of his comfortable apartment – to stare at strangers? He was mortified for himself, and still more mortified for them. Such an admission of inferiority! And why should they feel inferior? So far as money was concerned, weren’t they in as sound a position as anyone in the city? And as for ability – well, money like theirs wasn’t made nowadays by pinheads or duffers. James was probably the most astute business man you’d meet in a day’s march. There was no earthly reason why his family should play second fiddle to anyone in the room.

‘Look here!’ Theobald roused himself. As long as he was of the party, he might as well try to put some spirit into it. He leant across the table. ‘I heard an amusing thing today at the Courts,’ he said, determined to draw the attention of his family back to some common focus. To help his own concentration he fastened his eyes on a big plated cruet-stand on the table. His story might gather up their scattered attention and make it seem that they were interested in each other, that they had come here to enjoy each other’s company, to have a good meal, or even to listen to the music: anything, anything but expose themselves by gaping at other people. ‘I said I heard an amusing thing at the Courts this morning,’ he repeated, because his remark had passed unheard or unheeded the first time, the gaze of all the Beckers having at that moment gone towards a prominent actor who had just seated himself at an adjoining table. But Theobald’s simple ruse seemed doomed to failure. Only James appeared to be listening.

‘I didn’t think the Courts were sitting yet,’ James said. ‘I didn’t know the Long Vacation was over.’ In Theobald’s story he displayed no interest at all. He had done no more than, as it were, listlessly lift his fork to pick out a small morsel of familiar food before pushing aside the rest of what was offered.

Theobald did not know for a moment whether to be amused or annoyed. It might perhaps be an idea to try and make a joke of their inattention. If only he could rouse them to one good genuine laugh, he’d be satisfied. If only he could gather them for once into a self-absorbed group! But how? Just then, however, to his surprise he found Charlotte had been attending to what James had said.

‘Of course the Courts are sitting,’ she said, and the glance she gave her husband had an exasperated glint. Theobald was about to metaphorically link arms with her and enlist her as a supporter, when she leant forward to reprimand her husband. ‘How could you be so stupid, James? Didn’t you see the Chief Justice and his wife in the foyer when we were coming in here tonight? You know they wouldn’t be back in town unless the Supreme Court was sitting.’ But after another scathing glance she turned the other way, and this time leaning across Theobald, she caught Henrietta’s sleeve and gave it a tug. ‘They’re sitting at a table to the right of the door, Henrietta, if you’d like to see them. She has a magnificent ring on her finger. I can see it from here. And that’s their daughter in the velvet cloak. What do you think of her? She’s supposed to be pretty.’