Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

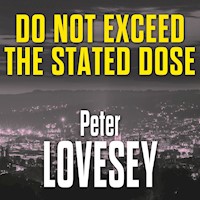

'What finer tribute could there be to five-star crime writer Lovesey than this magnificent collection of his short stories . Along with a dark strand of humour, the tingle of anticipation runs through the book. Every story builds to a climax that leaves you gasping' Daily Mail To celebrate a writing career spanning over fifty years, this collection showcases the very best of Peter Lovesey's short stories, featuring many of his most beloved characters such as Sergeant Cribb and Bertie. These inventive and entertaining stories have something for new and old fans alike. From unexpected discoveries hidden among the branches of the family tree, to a parrot and an astonishing cache of uncut diamonds, as well as the story of a marriage revealed between the lines of a Victorian advice column, these tales are all told with Lovesey's trademark wit. 'This splendid book is a wonderful compendium of good crime fiction that will give any aficionado a great deal of pleasure' Martin Edwards

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 761

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

1

THE BEST OF PETER LOVESEY STORIES

PETER LOVESEY

2

Contents

THINGS I ALREADY KNOW

Peter’s Notes

New writers are often told, ‘Write about what you know,’ and it’s not bad advice. To start this collection, here are three stories about topics familiar to me.

6

While researching family history I learned that it’s a great advantage having an unusual name. But imagine the difficulty if you happen to have the most common of all British surnames.

PL, 2025

How Mr Smith Traced His Ancestors

Most of the passengers were looking right, treating themselves to the breath-catching view of San Francisco Bay that the captain of the 747 had invited them to enjoy. Not Eva. Her eyes were locked on the lighted no-smoking symbol and the order to fasten seat belts. Until that was switched off she could not think of relaxing. She knew that the take-off was the most dangerous part of the flight, and it was a delusion to think you were safe the moment the plane was airborne. She refused to be distracted. She would wait for the proof that the take-off had been safely accomplished: the switching off of that small, lighted sign.

‘Your first time?’ The man on her left spoke with a West Coast accent. She had sensed that he had been waiting to speak since they took their seats, darting glances her way. Probably he was just friendly like most San Franciscans 8she had met on the trip, but she could not possibly start a conversation now.

Without turning, she mouthed a negative.

‘I mean your first time to England,’ he went on. ‘Anyone can see you’ve flown before, the way you put your hand luggage under the seat before they even asked us, and fixed your belt. I just wondered if this is your first trip to England.’

She didn’t want to seem ungracious. He was obviously trying to put her at ease. She smiled at the no-smoking sign and nodded. It was, after all, her first flight in this direction. The fact that she was English and had just been on a business trip to California was too much to explain.

‘Mine, too,’ he said. ‘Promised myself this for years. My people came from England, you see, forty, fifty years back. All dead now, the old folk. I’m the only one of my family left, and I ain’t so fit myself.’ He planted his hand on his chest. ‘Heart condition.’

Eva gave a slight start as an electronic signal sounded and the light went off on the panel she was watching. A stewardess’s voice announced that it was now permissible to smoke in the seats reserved for smoking, to the back of the cabin. Seat belts could also be unfastened. Eva closed her eyes a moment and felt the tension ease.

‘The doc says I could go any time,’ her companion continued. ‘I could have six months or six years. You know how old I am? Forty-two. When you hear something like that at my age it kinda changes your priorities. I figured I should do what I always promised myself – go to England and see if I had any people left over there. So here I am, and I feel like a kid again. Terrific.’9She smiled, mainly from the sense of release from her anxiety at the take-off, but also at the discovery that the man she was seated beside was as generous and open in expression as he was in conversation. In no way was he a predatory male. She warmed to him – his shining blue eyes in a round, tanned face topped with a patch of hair like cropped corn, his small hands holding tight to the armrests, his check Levi shirt bulging over the seat belt he had not troubled to unclasp. ‘You on a vacation too?’ he asked.

She felt able to respond now. ‘Actually I live in England.’

‘You’re English? How about that!’ He made it sound like one of the more momentous discoveries of his life, oblivious that there must have been at least a hundred Britons on the flight. ‘You’ve been on vacation in California, and now you’re travelling home?’

There was a ten-hour flight ahead of them, and Eva’s innately shy personality flinched at the prospect of an extended conversation, but the man’s candour deserved an honest reply. ‘Not exactly a vacation. I work in the electronics industry. My company wants to make a big push in the production of microcomputers. They sent me to see the latest developments in your country.’

‘Around Santa Clara?’

‘That’s right,’ said Eva, surprised that he should know. ‘Are you by any chance in electronics?’

He laughed. ‘No, I’m just one of the locals. The place is known as Silicon Valley, did you know that? I’m in farming, and I take an interest in the way the land is used. Excuse me for saying this: you’re pretty young to be representing your company on a trip like this.’10‘Not so young really. I’m twenty-eight.’ But she understood his reaction. She herself had been amazed when the Director of Research had called her into his office and asked her to make the trip. Some of her colleagues were equally astonished. The most incredulous was her flat-mate, Janet, suave, sophisticated Janet, who was on the editorial side at the Sunday Telegraph, and had been on assignments to Dublin, Paris and Geneva, and was always telling Eva how deadly dull it was to be confined to an electronics lab.

‘Wish I were twenty-eight,’ said her fellow traveller. ‘That was the year I was married. Patty was a wonderful wife to me. We had some great times.’

He paused in a way that begged Eva’s next question. ‘Something went wrong?’

‘She went missing three years back. Just disappeared. No note. Nothing. I came home one night and she was gone.’

‘That’s terrible.’

‘It broke me up. There was no accounting for it. We were very happily married.’

‘Did you tell the police?’

‘Yes, but they have hundreds of missing persons on their files. They got nowhere. I have to presume she is dead. Patty was happy with me. We had a beautiful home and more money than we could spend. I own two vineyards, big ones. We had grapes in California before silicon chips, you know.’

She smiled, and as it seemed that he didn’t want to speak any more about his wife, she said, ‘People try to grow grapes in England, but you wouldn’t think too much 11of them. When I left London the temperature was in the low fifties, and that’s our so-called summer.’

‘I’m not too interested in the weather. I just want to find the place where all the records of births, marriages and deaths are stored, so I can find if I have any family left.’

Eva understood now. This was not just the trip to England to acquire a few generations of ancestors and a family coat of arms. Here was a desperately lonely man. He had lost his wife and abandoned hope of finding her. But he was still searching for someone he could call his own.

‘Would that be Somerset House?’

His question broke through her thoughts.

‘Yes. That is to say, I think the records are kept now in a building in Kingsway, just a few minutes’ walk from there. If you asked at Somerset House, they’d tell you.’

‘And is it easy to look someone up?’

‘It should be, if you have names and dates.’

‘I figured I would start with my grandfather. He was born in a village called Edgecombe in Dorset in 1868, and he had three older brothers. Their names were Matthew, Mark and Luke, and I’m offering no prize for guessing what Grandfather was called. My pa was given the same name and so was I. Each of us was an only child. I’d like to find out if any of Grandfather’s brothers got married and had families. If they did, it’s possible that I have some second cousins alive somewhere. Do you think I could get this information?’

‘Well, it’s all there somewhere,’ said Eva.

‘Does it take long?’

‘That’s up to you. You have to find the names in the index 12first. That can take some time, depending how common the name is. Unfortunately, they’re not computerised. You just have to work through the lists.’

‘You’re serious?’

‘Absolutely. There are hundreds of enormous books full of names.’

For the first time in the flight, his brow creased into a frown.

‘Is something wrong?’ asked Eva.

‘Just that my name happens to be Smith.’

Janet thought it was hilarious when Eva told her. ‘All those Smiths! How long has he got, for God’s sake?’

‘In England? Three weeks, I think.’

‘He could spend the whole time working through the index and still get nowhere. Darling, have you ever been there? The scale of the thing beggars description. I bet he gives up on the first day.’

‘Oh, I don’t think he will. This was very important to him.’

‘Whatever for? Does he hope to get a title out of it? Lord Smith of San Francisco?’

‘I told you. He’s alone in the world. His wife disappeared. And he has a weak heart. He expects to die soon.’

‘Probably when he tries to lift one of those index volumes off the shelf,’ said Janet. ‘He must be out of his mind.’ She could never fathom why other people didn’t conform to her ideas of the way life should be conducted.

‘He’s no fool,’ said Eva. ‘He owns two vineyards, and in California that’s big business.’

‘A rich man?’ There was a note of respect in Janet’s voice.13‘Very.’

‘That begins to make sense. He wants his fortune to stay in the family – if he has one.’

‘He didn’t say that, exactly.’

‘Darling, it’s obvious. He’s over here to find his people and see if he likes them enough to make them his beneficiaries.’ Her lower lip pouted in a way that was meant to be amusing, but might have been involuntary. ‘Two vineyards in California! Someone stands to inherit all that, and doesn’t know a thing about it!’

‘If he finds them,’ said Eva. ‘From what you say, the chance is quite remote.’

‘Just about impossible, the way he’s going about it. You say he’s starting with the grandfather and his three brothers, and hoping to draw up a family tree. It sounds beautiful in theory, but it’s a lost cause. I happen to know a little about this sort of thing. When I was at Oxford I got involved in organising an exhibition to commemorate Thomas Hughes – Tom Brown’s Schooldays, right? I volunteered to try and find his descendants, just to see if they had any unpublished correspondence or photographs in the family. It seemed a marvellous idea at the time, but it was hopeless. I did the General Register Office bit, just like your American, and I discovered you simply cannot trace people that way. You can work backwards if you know the names and ages of the present generation, but it’s practically impossible to do it in reverse. That was with a name like Hughes. Imagine the problems with Smiths.’

Eva could see that Janet was right. She pictured John Smith III at his impossible task, and she was touched with 14pity. ‘There must be some other way he could do this.’

Janet grinned. ‘Like working through the phone book, ringing up all the Smiths?’

‘I feel really bad about this. I encouraged him.’

‘Darling, you couldn’t have done anything else. If this was the guy’s only reason for making the trip, you couldn’t tell him to abandon it before the plane touched down at Heathrow. Who knows – he might have incredible luck and actually chance on the right name.’

‘That would be incredible.’

Janet took a sip of the Californian wine Eva had brought back as duty-free. ‘Actually, there is another way.’

‘What’s that?’

‘Through parish records. He told you his grandfather was born somewhere in Dorset.’

‘Edgecombe.’

‘And the four brothers were named after the gospel writers, so it’s a good bet they were Church of England. Did all the brothers live in Edgecombe?’

‘I think so.’

‘Then it’s easy! Start with the baptisms. When was his grandfather born?’

‘1868.’

‘Right. Look up the Edgecombe baptisms for 1868. There can’t be so many John Smiths in a small Dorset village. You’ll get the father’s name in the register – he signs it, you see – and then you can start looking through other years for the brothers’ entries. That’s only the beginning. There are the marriage registers and the banns. If the Edgecombe register doesn’t have them, they could be in an adjoining parish.’15‘Hold on, Janet. You’re talking as if I’m going off to Dorset myself.’

Janet’s eyes shone. ‘Eva, you don’t need to go there. The Society of Genealogists in Kensington has copies of thousands of parish registers. Anyone can go there and pay a fee for a few hours in the library. I’ve got the address somewhere.’ She got up and went to her bookshelf.

‘Don’t bother,’ said Eva. ‘It’s John Smith who needs the information, not me, and I wouldn’t know how to find him now. He didn’t tell me where he’s staying. Even if I knew, I’d feel embarrassed getting in contact again. It was just a conversation on a plane.’

‘Eva, I despair of you. When it comes to the point, you’re so deplorably shy. I can tell you exactly where to find him: in the General Register Office in Kingsway, working through the Smiths. He’ll be there for the next three weeks if someone doesn’t help him out.’

‘Meaning me?’

‘No, I can see it’s not your scene. Let’s handle this another way. Tomorrow I’ll take a long lunch break and pop along to the Society of Genealogists to see if they have a copy of the parish registers for Edgecombe. If they haven’t, or there’s no mention of the Smith family, we’ll forget the whole thing.’

‘But if you do find something?’

‘Then we’ll consider what to do next.’ Casually, Janet added, ‘You know, I wouldn’t mind telling him myself.’

‘But you don’t know him.’

‘You could tell me what he looks like.’

‘How would you introduce yourself?’

‘Eva, you’re so stuffy! It’s easy in a place like that, 16where everyone is shoulder to shoulder at the indexes.’

‘You make it sound like a cocktail bar.’

‘Better.’

Eva couldn’t help smiling.

‘Besides,’ said Janet. ‘I do have something in common with him. My mother’s maiden name was Smith.’

The search rooms of the General Register Office were filled with the steady sound of index volumes being lifted from the shelves, deposited on the reading tables and then returned. There was an intense air of industry as the searchers worked up and down the columns of names, stopping only to note some discovery that usually was marked by a moment of reflection, followed by redoubled activity.

Janet had no trouble recognising John Smith. He was where she expected to find him: at the indexes of births for 1868. He was the reader with one volume open in front of him that he had not exchanged in ten minutes. Probably not all morning. His stumpy right hand, wearing three gold rings, checked the rows of Victorian copperplate at a rate appropriate to a marathon effort. But when he turned a page he shook his head and sighed.

Eva had described him accurately enough without really conveying the total impression he made on Janet. Yes, he was short and slightly overweight and his hair was cut to within a half-inch of his scalp, yet he had a teddy-bear quality that would definitely help Janet to be warm towards him. Her worry had been that he would be too pitiable.

She waited for the person next to him to return a volume, then moved to his side, put down the notebook 17she had brought, and asked him, ‘Would you be so kind as to keep my place while I look for a missing volume? I think someone must have put it back in the wrong place.’

He looked up, quite startled to be addressed. ‘Why, sure.’

Janet thanked him and walked round to the next row of shelves.

In a few minutes she was back. ‘I can’t find it. I must have spent twenty minutes looking for it, and my lunch-hour will be over soon.’

He kept his finger against the place of birth he had reached and said, ‘Maybe I could help. Which one are you looking for, miss?’

‘Could you? It’s P to S for the second quarter of 1868.’

‘Really? I happen to have it right here.’

‘Oh, I didn’t realise …’ Janet managed to blush a little.

‘Please.’ He slid the book in front of her. ‘Go ahead; I have all day for this. Your time is more valuable than mine.’

‘Well, thank you.’ She turned a couple of pages. ‘Oh dear, this is going to be much more difficult than I imagined. Why did my mother have to be born with a name as common as Smith?’

‘Your name is Smith?’ He beamed at the discovery, then nodded. ‘I guess it’s not such a coincidence.’

‘My mother’s name, actually. I’m Janet Murdoch.’

‘John Smith.’ He held out his hand. ‘I’m a stranger here myself, but if I can help in any way…’

Janet said, ‘I’m interested in tracing my ancestors, but looking at this, I think I’d better give up. My great-grandfather’s name was Matthew Smith, and there are 18pages and pages of them. I’m not even sure of the year he was born. It was either 1868 or 1869.’

‘Do you know the place he was born?’

‘Somewhere in Dorset. Wait, I’ve got it written here.’ She opened the notebook to the page where she had made her notes at the Society of Genealogists. ‘Edgecombe.’

‘May I see that?’ John Smith held it and his hand shook. ‘Janet, I’m going to tell you something that you’ll find hard to believe.’

He took her to lunch at Rules. It tested her nerve as he questioned her about Matthew Smith of Edgecombe, but she was well prepared. She said she knew there had been four brothers, only she was deliberately vague about their names. Two, she said, had married, and she was the solitary survivor of Matthew’s line.

John Smith ate very little lunch. Most of the time, he sat staring at Janet and grinning. He was very like a teddy bear. She found it pleasing at first, because it seemed to show he was a little light-headed at the surprise she had served him. As the meal went on, it made her feel slightly uneasy, as if he had something in mind that she had not foreseen.

‘I have an idea,’ he said, just before they got up to leave, ‘only I hope you won’t get me wrong, Janet. What I would like is to go out to Dorset at the weekend and find Edgecombe, and have you come with me. Maybe we could locate the church and see if they still have a record of our people. Would you come with me?’

It suited her perfectly. The parish records would confirm everything she had copied at the Society of Genealogists. Any doubts John Smith might have of her 19integrity would be removed. And if her information on the Smiths of Edgecombe was shown to be correct, no suspicion need arise that she was not related to them at all. John Smith would accept her as his sole surviving relative. He would return to California in three weeks with his quest accomplished. Sooner or later Janet would inherit two vineyards and a fortune.

‘It’s a wonderful idea! I’ll be delighted to come.’

Nearly a fortnight passed before Eva started to be anxious about Janet’s absence. Once or twice before, she had gone away on assignments for the newspaper without saying that she was going: secretly Eva suspected she did it to make her work seem more glamorous – the sudden flight to an undisclosed destination on a mission so delicate that it could not be whispered to a friend. But this time the Sunday Telegraph called to ask why Janet had not been seen at the office for over a week.

When they called again a day or two later, and Eva still had no news, she decided she had no choice but to make a search of Janet’s room for some clues as to her whereabouts. At least she would see which clothes Janet had taken – whether she had packed for a fortnight’s absence. With luck she might find a note of the flight number.

The room was in its usual disorder, as if Janet had just gone for a shower and would sweep in at any moment in her white Dior bathrobe. By the phone, Eva found the calendar Janet used to jot down appointments. There was no entry for the last fortnight. On the dressing table was her passport. The suitcase she always took on trips of a week or more was still on top of the wardrobe.20Janet was not the sort of person you worried over, but this was becoming a mystery. Eva systematically searched the room, and found no clue. She phoned the Sunday Telegraph and told them she was sorry she could not help. As she put down the phone, her attention was taken by the letters beside it. She had put them there herself, the dozen or so items of mail that had arrived for Janet.

Opening someone else’s private correspondence was a step up from searching their room, and she hesitated. What right had she to do such a thing? She could tell by the envelopes that two were from the Inland Revenue, and she put them back by the phone. Then she noticed one addressed by hand. It was postmarked Edgecombe, Dorset.

Her meeting with the friendly Californian named John Smith had been pushed to the edge of her memory by more immediate matters, and it took a few moments’ thought to recall the significance of Edgecombe. Even then, she was baffled. Janet had told her that Edgecombe was a dead end. She had checked it at the Society of Genealogists. It had no parish register because there was no church there. They had agreed to drop their plan to help John Smith trace his ancestors.

But why should Janet receive a letter from Edgecombe?

Eva decided to open it.

The address on the headed notepaper was The Vicarage, Edgecombe, Dorset.

Dear Miss Murdoch,

I must apologise for the delay in replying to your letter. I fear that this may arrive after you have 21left for Dorset. However, it is only to confirm that I shall be pleased to show you the entries in our register pertaining to your family, although I doubt if we have anything you have not seen at the Society of Genealogists.

Yours sincerely,

Denis Harcourt, Vicar

A dead end? No church in Edgecombe?

Eva decided to go there herself.

The Vicar of Edgecombe had no difficulty in remembering Janet’s visit. ‘Yes, Miss Murdoch called on a Saturday afternoon. At the time, I was conducting a baptism, but they waited until it was over and I took them to the vicarage for a cup of tea.’

‘She had someone with her?’

‘Her cousin.’

‘Cousin?’

‘Well, I gather he was not a first cousin, but they were related in some way. He was from America, and his name was John Smith. He was very appreciative of everything I showed him. You see, his father and his grandfather were born here, so I was able to look up their baptisms and their marriages in the register. It goes back to the sixteenth century. We’re very proud of our register.’

‘I’m sure you must be. Tell me, did Janet – Miss Murdoch – claim to be related to the Smiths of Edgecombe?’

‘Certainly. Her great-grandfather, Matthew Smith, is buried in the churchyard. He was the brother of the 22American gentleman’s grandfather, if I have it right.’

Eva felt the anger like a kick in the stomach. Not only had Janet Murdoch deceived her. She had committed an appalling fraud on a sweet-natured man. And Eva herself had passed on the information that enabled her to do it. She would never forgive her for this.

‘That’s the only Smith grave we have in the churchyard,’ the Vicar continued. ‘When I first got Miss Murdoch’s letter, I had hopes of locating the stones of the two John Smiths, the father and grandfather of our American visitor, but it was not to be. They were buried elsewhere.’

Something in the Vicar’s tone made Eva ask, ‘Do you know where they were buried?’

‘Yes, indeed. I got it from Mr Harper, the Sexton. He’s been here much longer than I.’

There was a pause.

‘Is it confidential?’ Eva asked.

‘Not really.’ The Vicar eased a finger round his collar, as if it were uncomfortable. ‘It was information that I decided in the circumstances not to volunteer to Miss Murdoch and Mr Smith. You are not one of the family yourself?’

‘Absolutely not.’

‘Then I might as well tell you. It appears that the first John Smith developed some form of insanity. He was given to fits of violence and became quite dangerous. He was committed to a private asylum in London and died there a year or two later. His only son, the second John Smith, also ended his life in distressing circumstances. He was convicted of murdering two local girls by strangulation, and there was believed to have been a third, but the charge was never brought. He was found guilty but 23insane, and sent to Broadmoor. To compound the tragedy, he had a wife and baby son. They went to America after the trial.’ The Vicar gave a shrug. ‘Who knows whether the child was ever told the truth about his father, or his grandfather, for that matter? Perhaps you can understand why I was silent on the matter when Mr Smith and Miss Murdoch were here. I may be old-fashioned, but I think the pyschiatrists make too much of heredity, don’t you? If you took it seriously, you’d think no woman was safe with Mr Smith.’

From the vicarage, Eva went straight to the house of the Edgecombe police constable and told her story.

The officer listened patiently. When Eva had finished, he said, ‘Right, miss. I’ll certainly look into it. Just for the record: this American – what did he say his name was?’

24

I admit with shame that as a child, before many species of butterfly became endangered, I collected them. It was my ambition to catch a purple emperor. I never did, because they aren’t often seen at ground level.

PL, 2025

A Case of Butterflies

Before calling the police, he had found a butterfly in the summerhouse. It had unsettled him. The wings had been purple, a rich, velvety purple. Soaring and swooping, it had intermittently come to rest on the wood floor. His assumption that it was trapped had proved to be false, because two of the windows had been wide open and it had made no move towards the open door. He knew what it was, a Purple Emperor, for there was one made of paper mounted in a perspex case in his wife Ann’s study. As a staunch conservationist, Ann wouldn’t have wanted to possess a real specimen. She had told him often enough that she preferred to see them flying free. She had always insisted that Purple Emperors were in the oak wood that surrounded the house. He had never spotted one until this morning, and it seemed like a sign from her.26

‘You did the right thing, sir.’

‘The right thing?’

‘Calling us in as soon as you knew about this. It takes courage.’

‘I don’t want your approval, Commander. I want my wife back.’

‘We all want that, sir.’

Sir Milroy Shenton made it plain that he didn’t care for the remark, mildly as it was put. He rotated his chair to turn his back on the two police officers and face the view along King’s Reach where the city skyline rises above Waterloo Bridge. He stared at it superficially. The image of the butterfly refused to leave his mind, just as it had lingered in the summerhouse. Less than an hour ago he had called the emergency number from his house in Sussex. The police had suggested meeting in London in case the house was being observed, and he had nominated the Broad Wall Complex. He had the choice of dozens of company boardrooms across London and the Home Counties that belonged in his high-tech empire. The advantage of using Broad Wall was the proximity of the heliport.

He swung around again. ‘You’ll have to bear with me. I’m short of sleep. It was a night flight from New York.’

‘Let’s get down to basics, then. Did you bring the ransom note?’

Commander Jerry Glazier was primed for this. He headed the Special Branch team that was always on stand-by to deal with kidnapping incidents. International terrorism was so often involved in extortion that a decision had been taken to involve Special Branch from the beginning in major kidnap inquiries. Captains of industry 27like Shenton were obvious targets. They knew the dangers, and often employed private bodyguards. Not Shenton: such precautions would not square with his reputation in the city as a devil-may-care dealer in the stock market, known and feared for his dawn raids.

Glazier was assessing him with a professional eye, aware how vital in kidnap cases is the attitude and resolve of the ‘mark’.

First impressions suggested that this was a man in his forties trying to pass for twenty-five, with a hairstyle that would once have been called short back and sides and was now trendy and expensive. A jacket of crumpled silk was hanging off his shoulders. The accent was Oxford turned cockney, a curious inversion Glazier had noted lately in the business world. Scarcely ten minutes ago he had read in Who’s Who that Shenton’s background was a rectory in Norfolk, followed by Winchester and Magdalen. He had married twice. The second wife, the lady now abducted, was Ann, the only daughter of Dr Hamilton Porter, deceased. Under Recreations, Shenton had entered Exercising the wife. It must have seemed witty when he thought of it.

Now he took a package from his pocket. ‘Wrapped in a freezer bag, as your people suggested. My sweaty prints are all over it, of course. I didn’t know it was going to be evidence until I’d read the bloody thing, did I?’

‘It isn’t just the prints.’ Glazier glanced at the wording on the note. It read:

IF YOU WANT HER BACK ALIVE GET ONE MILLION READY. INSTRUCTIONS FOLLOW.28

‘There’s modern technology for you,’ he commented. ‘They do the old thing of cutting words from the papers, but now they dispense with paste. They use a photocopier.’ He turned it over to look at the envelope. ‘Indistinct postmark, wouldn’t you know.’

‘The bastards could have sent it any time in the last six days, couldn’t they?’ said Shenton. ‘For all I know, they may have tried to phone me. She could be dead.’

Glazier wasn’t there to speculate. ‘So you flew in from New York this morning, returned to your house and found this on the mat?’

‘And my wife missing.’

‘You’ve been away from the house for how long, sir?’

‘I told you – six days. Ann had been away as well, but she should have been back by now.’

‘Then I dare say there was a stack of mail waiting.’

‘Is that relevant?’

The pattern of the interview was taking shape. Shenton was using every opportunity to assert his status as top dog.

‘It may be,’ Glazier commented, ‘if you can remember what was above or below it in the stack.’ He wasn’t to be intimidated.

‘I just picked everything up, flipped through what was there and extracted the interesting mail from the junk.’

‘This looked interesting?’

‘It’s got a stamp, hasn’t it?’

‘Fair enough. You opened it, read the note, and phoned us. Did you call anyone else?’

‘Cressie.’

‘Cressie?’29

‘Cressida Concannon, Ann’s college friend. The two of them were touring.’

‘Touring where, sir?’

‘The Ring of Kerry.’

‘Ireland?’ Glazier glanced towards his assistant, then back at Shenton. ‘That was taking a chance, wasn’t it?’

‘With hindsight, yes. I told Ann to use her maiden name over there.’

‘Which is …?’

‘Porter.’

‘So what have you learned from her friend?’

‘Cressie’s still over there, visiting her sister. She last saw Ann on Wednesday at the end of their holiday, going in to Cork airport.’

‘Have you called the airline to see if she was on the flight?’

Shenton shook his head. ‘Tracing Cressie took the best part of half an hour. I flew straight up from Sussex after that.’

‘Flew?’

‘Chopper.’

‘I see. Did your wife have a reservation?’

‘Aer Lingus. The two-fifteen flight to Heathrow.’

Glazier nodded to his assistant, who left the room to check. ‘This holiday in Ireland – when was it planned?’

‘A month ago, when New York came up. She said she deserved a trip of her own.’

‘So she got in touch with her friend. I shall need to know more about Miss Concannon, sir. She’s an old and trusted friend, I take it?’

‘Cressie? She’s twenty-four carat. We’ve known her for twelve years, easily.’30

‘Well enough to know her political views?’

‘Hold on.’ Shenton folded his arms in a challenging way. ‘Cressie isn’t one of that lot.’

‘But does she guard her tongue?’

‘She’s far too smart to mouth off to the micks.’

‘They met at college, you say. What were they studying?’

‘You think I’m going to say politics?’ Shenton said as if he were scoring points at a board meeting. ‘It was bugs. Ann and Cressie’s idea of a holiday is kneeling in cowpats communing with dung-beetles.’

‘Entomology,’ said Glazier.

‘Sorry, I was forgetting some of the fuzz can read without moving their lips.’

‘Do you carry a picture of your wife, sir?’

‘For the press, do you mean? She’s been kidnapped. She isn’t a missing person.’

‘For our use, Sir Milroy.’

He felt for his wallet. ‘I dare say there’s one I can let you have.’

‘If you’re bothered about the media, sir, we intend to keep them off your back until this is resolved. The Press Office at the Yard will get their co-operation.’

‘You mean an embargo?’ He started to remove a photo from his wallet and then pushed it back into its slot. Second thoughts, apparently.

Glazier had glimpsed enough of the print to make out a woman in a see-through blouse. She seemed to be dancing. ‘I mean a voluntary agreement to withhold the news until you’ve got your wife back. After that, of course …’

‘If I get her back unharmed I’ll speak to anyone.’

‘Until that happens, you talk only to us, sir. These 31people, whoever they are, will contact you again. Do you have an answerphone at your house?’

‘Of course.’

‘Have you played it back?’

‘Didn’t have time.’ Shenton folded the wallet and returned it to his pocket. ‘I don’t, after all, happen to have a suitable picture of Ann on me. I’ll arrange to send you one.’

‘Listen to your messages as soon as you get back, sir, and let me know if there’s anything.’

‘What do you do in these cases – tap my phone?’

‘Is that what you’d recommend?’

‘Commander Glazier, don’t patronise me. I called you in. I have a right to know what to expect.’

‘You can expect us to do everything within our powers to find your wife, sir.’

‘You don’t trust me, for God’s sake?’

‘I didn’t say that. What matters is that you put your trust in us. Do you happen to have a card with your Sussex address?’

Shenton felt for the wallet again and opened it.

Glazier said at once, ‘Isn’t that a picture of your wife, sir, the one you put back just now?’

‘That wasn’t suitable. I told you.’

‘If it’s the way she’s dressed that bothers you, that’s no problem. I need the shot of her face, that’s all. May I take it?’

Shenton shook his head.

‘What’s the problem?’ asked Glazier.

‘As it happens, that isn’t Ann. It’s her friend Cressida.’ 32

Between traffic signals along the Embankment, Glazier told his assistant, Inspector Tom Salt, about the photograph.

‘You think he’s cheating with his wife’s best friend?’

‘It’s a fair bet.’

‘Does it have any bearing on the kidnap?’

‘Too soon to tell. His reactions are strange. He seems more fussed about how we intend to conduct the case than what is happening to his wife.’

‘High-flyers like him operate on a different level from you and me, sir. Life is all about flow-charts and decision-making.’

‘They’re not all like that. Did you get anything from the airline?’

‘Everything he told us checks. There was a first class reservation in the name of Ann Porter. She wasn’t aboard that Heathrow flight or any other.’

The next morning Glazier flew to Ireland for a meeting with senior officers in the gardai. Cork airport shimmered in the August heat. At headquarters they were served iced lemonade in preference to coffee. A full-scale inquiry was authorised.

He visited Cressida Concannon at her sister’s, an estate house on the northern outskirts of Cork, and they talked outside, seated on patio chairs. She presented a picture distinctly different from the photo in Shenton’s wallet; she was in a cream-coloured linen suit and brown shirt buttoned to the top. Her long brown hair was drawn back and secured with combs. Like Lady Ann, she was at least ten years younger than Shenton. She had made an itinerary of the tour around the Ring of Kerry. She handed Glazier a sheaf of hotel receipts.33

He flicked through them. ‘I notice you paid all of these yourself, Miss Concannon.’

‘Yes. Ann said she would settle up with me later. She couldn’t write cheques because she was using her maiden name.’

‘Of course. Porter, isn’t it? So the hotel staff addressed her as Mrs Porter?’

‘Yes.’

‘And was there any time in your trip when she was recognised as Lady Shenton?’

‘Not to my knowledge.’

‘You remember nothing suspicious, nothing that might help us to find her?’

‘I’ve been over it many times in my mind, and I can’t think of anything, I honestly can’t.’

‘What was her frame of mind? Did she seem concerned at any stage of the tour?’

‘Not once that I recall. She seemed to relish every moment. You can ask at any of the hotels. She was full of high spirits right up to the minute we parted.’

‘Which was …?’

‘Wednesday, about twelve-thirty. I drove her to the airport and put her down where the cars pull in. She went through the doors and that was the last I saw of her. Surely they won’t harm her, will they?’

Glazier said as if he hadn’t listened to the question, ‘Tell me about your relationship with Sir Milroy Shenton.’

She drew herself up. ‘What do you mean?’

‘You’re a close friend, close enough to spend some time alone with him, I believe.’

‘They are both my friends. I’ve known them for years.’34

‘But you do meet him, don’t you?’

‘I don’t see what this has to do with it.’

‘I’ll tell you,’ said Glazier. ‘I’m just surprised that she went on holiday with you and relished every moment, as you expressed it. She’s an intelligent woman. He carries your picture fairly openly in his wallet. He doesn’t carry one of Lady Ann. Her behaviour strikes me as untypical, that’s all.’

She said coolly, ‘When you rescue her from the kidnappers, you’ll be able to question her about it, won’t you?’

Before leaving Ireland, Glazier had those hotels checked. Without exception the inquiries confirmed that the two women had stayed there on the dates in question. Moreover, they had given every appearance of getting on well together. One hotel waiter in Killarney recalled that they had laughed the evenings away together.

Within an hour of Glazier’s return to London, there was a development. Sir Milroy Shenton called on the phone. His voice was strained. ‘I’ve heard from them. She’s dead. They’ve killed her, the bastards, and I hold you responsible.’

‘Dead? You’re sure?’

‘They’re sure.’

‘Tell me precisely how you heard about this.’

‘They just phoned me, didn’t they? Irish accent.’

‘A man?’

‘Yes. Said they had to abort the operation because I got in touch with the filth. That’s you. They said she’s at the bottom of the Irish Sea. This is going to be on your conscience for the rest of your bloody life.’35

‘I need to see you,’ said Glazier. ‘Where are you now?’

‘Manchester.’

‘How do they know you’re up there?’

‘It was in the papers. One of my companies has a shareholders’ meeting. Look, I can’t tell you any more than I just did.’

‘You want the killers to get away with it, sir?’

‘What?’

‘I’ll be at Midhurst. Your house.’

‘Why Midhurst?’

‘Get there as soon as you can, Sir Milroy.’ Glazier put an end to the call and stabbed out Tom Salt’s number. ‘Can you lay on a chopper, Tom?’

‘What’s this about?’ Salt shouted over the engine noise after they were airborne.

‘Shenton. His wife is dead.’

‘Why would they kill her? While she was alive she was worth a million.’

‘My thought exactly.’

Salt wrestled with that remark as they followed the ribbon of the Thames southwards, flying over Richmond and Kingston. ‘Don’t you believe what Shenton told you?’

‘She’s dead. I believe that much.’

‘No kidnap?’

‘No kidnap.’

‘We’re talking old-fashioned murder, then.’

‘That’s my reading of it.’

There was a break in the conversation that brought them across the rest of Surrey before Salt shouted, ‘It’s got to be Cressie Concannon, hasn’t it?’

‘Why?’36

‘She wasn’t satisfied with her status as the mistress, so she snuffed her rival and sent the ransom note to cover up the crime.’

Glazier shook his head. ‘Cressie is in Ireland.’

‘What’s wrong with that? Lady Shenton was last seen in Ireland. We know she didn’t make the flight home.’

‘Cressie didn’t send the ransom note. The postage stamp was British.’

The pilot turned his head. ‘The place should be coming up any minute, sir. Those are the South Downs ahead.’

Without much difficulty they located Shenton’s house, a stone-built Victorian mansion in a clearing in an oak wood. The helicopter wheeled around it once before touching down on the forecourt, churning up dust and gravel.

‘We’ve got at least an hour before he gets here,’ Glazier said.

‘Is there a pub?’ asked Salt, and got a look from his superior that put him off drinking for a week.

Rather less than the estimated hour had passed when the clatter of a second helicopter disturbed the sylvan peace. Glazier crossed the drive to meet it.

‘No more news, I suppose?’ Sir Milroy Shenton asked as he climbed out. He spoke in a more reasonable tone than he’d used on the phone. He’d had time to compose himself.

‘Not yet, sir.’

‘Found your way in?’

‘No, we’ve been out here in the garden.’

‘Not much of a garden. Ann and I preferred to keep it uncultivated except for the lawns.’37

‘She must have wanted to study the insect life in its natural habitat.’

Shenton frowned slightly, as if he’d already forgotten about his wife’s field of study. ‘Shall we go indoors?’

A fine curved staircase faced them as they entered. The hall was open to three floors. ‘Your wife had a study, I’m sure,’ said Glazier. ‘I’d like to see it, please.’

‘To your left – but there’s nothing in there to help you,’ said Shenton.

‘We’ll see.’ Glazier entered the room and moved around the desk to the bookshelves. ‘Whilst we were waiting for you I saw a couple of butterflies I’d never spotted before. I used to collect them when I was a kid, little horror, before they were protected. Did you know you had Purple Emperors here?’

Shenton twitched and swayed slightly. Then he put his hand to his face and said distractedly, ‘What?’

‘Purple Emperors. There were two in the summerhouse just now. The windows were open, but they had no desire to leave. They settled on the floor in the joints between the boards.’ Glazier picked a book off the shelf and thumbed through the pages, finally turning them open for Shenton’s inspection. ‘How about that? Isn’t it superb? The colour on those wings! I’d have sold my electric train-set for one of these in my collection.’ He continued to study the page.

‘You must have lived in the wrong area,’ said Shenton, with an effort to sound reasonable.

‘I wouldn’t say that,’ said Glazier. ‘There were oaks in the park where I played. They live high up in the canopy of the wood. You never see them normally, but they are probably more common than most of us realised then.’38

‘This isn’t exactly helping to find my wife,’ said Shenton.

‘You couldn’t be more wrong,’ said Glazier. ‘How long ago did you kill her, Sir Milroy?’

Shenton tensed. He didn’t respond.

‘She’s been dead a few weeks, hasn’t she? Long before your trip to New York. She didn’t visit Ireland at all. That was some friend of Cressida Concannon’s, using the name of Ann Porter. A free trip around the Ring of Kerry. No wonder the woman was laughing. She must have thought the joke was on you, just as the expenses were. I don’t suppose she knew that the real Lady Ann was dead.’

‘I don’t have to listen to this slanderous rubbish,’ said Shenton. He’d recovered his voice, but he was ashen.

‘You’d better. I’m going to charge you presently. Miss Concannon will also be charged as an accessory. The kidnapping was a fabrication. You wrote the ransom note yourself some time ago. You posted envelopes to this address until one arrived in the condition you required – with the indistinct date-stamp. Then all you had to do was slip the ransom note inside and hand it to me when you got back from New York and alerted us to your wife’s so-called abduction. How long has she been dead – four or five weeks?’

Shenton said with contempt, ‘What am I supposed to have done with her?’

‘Buried her – or tried to. You weren’t the first murderer to discover that digging a grave isn’t so easy if the ground is unhelpful. It’s always a shallow grave in the newspaper reports, isn’t it? But you didn’t let that defeat you. You jacked up the summerhouse and wedged her under the 39floorboards – which I suppose was easier than digging six feet down. The butterflies led me to her.’

Shenton latched on to this at once. Turning to Tom Salt he said, ‘Is he all right in the head?’

Salt gave his boss a troubled glance.

Shenton flapped his hand in derision. ‘Crazy.’

‘You don’t believe me?’ said Glazier. ‘Why else would a Purple Emperor come down from the trees? Listen to this.’ He started reading from the book. ‘“They remain in the treetops feeding on sap and honeydew unless attracted to the ground by the juices of dung or decaying flesh. They seldom visit flowers.”’ He looked up, straight into Shenton’s stricken eyes. ‘Not so crazy after all, is it?’

40

In old age, I am deaf, which is a drag, but there’s humour to be had from it, and I had more fun writing this story than any other.

PL, 2025

Say That Again

We called him the Brigadier with the buggered ear. Just looking at it made you wince. Really he should have had the bits surgically removed. He claimed it was an old war wound. However, Sadie the Lady, another of our residents, told us it wasn’t true. She said she’d talked to the Brig’s son, Arnold, who reckoned his old man got blind drunk in Aldershot one night and tripped over a police dog and paid for it with his shell-like.

Because of his handicap, the Brigadier tended to shout. His ‘good’ ear wasn’t up to much, even with the aid stuck in it. We got used to the shouting, we old farts in the Never-Say-Die Retirement Home. After all, most of us are hard of hearing as well. No doubt we were guilty of letting him bluster and bellow without interruption. We never dreamed at the time that our compliance would get 42us into the High Court on a murder rap.

It was set in motion by She-Who-Must-Be-Replaced, our so-called matron, pinning a new leaflet on the notice board in the hall.

‘Infernal cheek!’ the Brig boomed. ‘They’re parasites, these people, living off the frail and weak-minded.’

‘Who are you calling weak-minded?’ Sadie the Lady piped up. ‘There’s nothing wrong with my brain.’

The Brig didn’t hear. Sometimes it can be a blessing.

‘Listen to this,’ he bellowed, as if we had any choice. ‘“Are you dissatisfied with your hearing? Struggling with a faulty instrument? Picking up unwanted background noise? Marcus Haliburton, a renowned expert on the amazing new digital hearing aids, will be in attendance all day at the Bay Tree Hotel on Thursday, 8th April for free consultations. Call this number now for an appointment. No obligation.” No obligation, my arse – forgive me, ladies. You know what happens? They get you in there and tell you to take out your National Health aid so they can poke one of those little torches in your ear and of course you’re stuffed. You can’t hear a thing they’re saying from that moment on. The next thing is they shove a form in front of you and you find you’ve signed an order for a thousand pound replacement. If you object they drop your NHS aid on the floor and tread on it.’

‘That can’t be correct,’ Miss Martindale said.

‘Completely wrecked, yes,’ the Brigadier said. ‘Are you speaking from personal experience, my dear? Because I am.’

Someone put up a hand. He wanted to be helped to the toilet, but the Brigadier took it as support. ‘Good man. 43What we should do is teach these blighters a lesson. We could, you know, with my officer training and George’s underworld experience.’

I smiled faintly. My underworld links were nil, another of the Brig’s misunderstandings. One afternoon I’d been talking to Sadie about cats and happened to mention that we once adopted a stray. I thought the Brig was dozing in his armchair, but he came to life and said, ‘Which of the Krays was that – Reggie or Ronnie? I had no idea of your criminal past, George. We’ll have to watch you in future.’

It was hopeless trying to disillusion him, so I settled for my gangster reputation and some of the old ladies began to believe it, too, and found me more interesting than ever they’d supposed.

By the next tea break, the Brigadier had turned puce with excitement. ‘I’ve mapped it out,’ he told us. ‘I’m calling it Operation Syringe, because we’re going to clean these ruffians out. Basically, the object of the plan is to get a new super-digital hearing aid for everyone in this home free of charge.’

‘How the heck will you do that?’ Sadie asked.

‘What?’

She stepped closer and spoke into his ear. ‘They’re a private company. Those aids cost a fortune.’

The Brig grinned. ‘Simple. We intercept their supplies. I happen to know the Bay Tree Hotel quite well.’

Sadie said to the rest of us, ‘That’s a fact. The Legion has its meetings there. He’s round there every Friday night for his g&t.’

‘G&T or two or three,’ another old lady said.

I said, ‘Wait a minute, Brigadier. We can’t steal a bunch 44of hearing aids.’ I have a carrying voice when necessary and he heard every word.

‘“Steal” is not a term in the military lexicon, dear boy,’ he said. ‘We requisition them.’ He leaned forward. ‘Now, the operation has three phases. Number One: Observation. I’ll take care of that. Number Two: Liaison. This means getting in touch with an inside man, Cormac, the barman. I can do that also. Number Three: Action. And that depends on what we learn from Phases One and Two. That’s where the rest of you come in. Are you with me?’

‘I don’t know what he’s on about,’ Sadie said to me.

‘Don’t worry,’ I said. ‘He’s playing soldiers, that’s all. He’ll find out it’s a non-starter.’

‘No muttering in the ranks,’ the Brigadier said. ‘Any dissenters? Fall out, the dissenters.’

No one moved. Some of us needed help to move anywhere and nobody left the room when tea and biscuits were on offer. And that was how we were recruited into the snatch squad.

On Saturday, the Brigadier reported on Phases One and Two of his battle plan. He marched into the tea room looking as chipper as Montgomery on the eve of El Alamein.

‘Well, the obbo phase is over and so is the liaison and I’m able to report some fascinating results. The gentleman who wants us all to troop along to the Bay Tree Hotel and buy his miraculous hearing aids is clearly doing rather well out of it. He drives a vintage Bentley and wears a different suit each visit and by the cut of them they’re not off the peg.’

‘There’s money in ripping off old people,’ Sadie said.45

‘It ought to be stopped,’ her friend Briony said.

The Brig went on, ‘I talked to my contact last night and I’m pleased to tell you that the enemy – that is to say Marcus Haliburton – works to a predictable routine. He puts in a fortnightly appearance at the Bay Tree. If you go along and see him you’ll find Session One is devoted to the consultation and the placing of the order. Session Two is the fitting and payment. Between Sessions One and Two a box is delivered to the hotel and it contains up to fifty new hearing aids – more than enough for our needs.’ He paused and looked around the room. ‘So what do you think is the plan?’

No one was willing to say. Some might have thought speaking up would incriminate them. Others weren’t capable of being heard by the Brigadier. Finally I said, ‘We, em, requisition the box?’

‘Ha!’ He lifted a finger. ‘I thought you’d say that. We can do better. What we do is requisition the box.’

There were smiles all round at my expense.

‘And then,’ the Brigadier said, ‘we replace the box with one just like it.’

‘That’s neat,’ Sadie said. She was beginning to warm to the Brigadier’s criminal scheme.

He’d misheard her again. ‘It may sound like deceit to you, madam, but to some of us it’s common justice. They called Robin Hood a thief.’

‘Are we going to be issued with bows and arrows?’ Sadie said.

‘I wouldn’t mind meeting some merry men,’ Briony said.

The Brigadier’s next move took us all by surprise. ‘Check the corridor, George. Make sure no staff are about.’46

I did as I was told and gave the thumbs-up sign, whereupon the old boy bent down behind the sideboard and dragged out a flattened cardboard box that he rapidly restored to its normal shape.

‘Thanks to my contacts at the hotel I’ve managed to retrieve the box that was used to deliver this week’s aids.’ No question: he intended to go through with this crazy adventure. In the best officer tradition he started to delegate duties. ‘George, your job will be to get this packed and sealed and looking as if it just arrived by courier.’

‘No problem,’ I said to indulge him. I was sure the plan would break down before I had to do anything.

‘That isn’t so simple as it sounds,’ he said. ‘Take a close look. The aids are made in South Africa, so there are various customs forms attached to the box. They stuff them in a kind of envelope and stick them to the outside. What you do is update this week’s documents.’

‘I’ll see what I can manage.’

‘Then you must consider the contents. The instruments don’t weigh much, and they’re wrapped in bubblewrap, so the whole thing is almost as light as air. Whatever you put inside must not arouse suspicion.’

‘Crumpled-up newspaper,’ Sadie said.

‘What did she say?’

I repeated it for his benefit.

Sadie said, ‘Briony has a stack of Daily Mails this high in her room. She hoards everything.’

I knew that to be true. Briony kept every postcard, every letter, every magazine. Her room was a treasure house of things other people discarded. She even collected the tiny jars our breakfast marmalade came in. The only question 47was whether she would donate her newspaper collection to Operation Syringe. She could be fiercely possessive at times.

‘I might be able to spare you some of the leaflets that come with my post,’ she said.

Sadie said, ‘Junk mail. That’ll do.’

‘It doesn’t incriminate me, does it?’ she said. ‘I want no part of this silly escapade.’

‘Excellent,’ the Brigadier said, oblivious. ‘When the parcel is up to inspection standard, I’ll tell you about the next phase.’

The heat was now on me. I had to smuggle the box back to my room and start work. I was once employed as a graphic designer, so the forging of the forms wasn’t a big problem. Getting Briony to part with her junk mail was far more demanding. You’d think it was bank notes. She checked everything and allowed me about one sheet in five. But in the end I had enough to stuff the box. I sealed it with packing tape I found in Matron’s office and showed it to the Brigadier.

‘Capital,’ he said. ‘We can proceed to phase four: distracting the enemy.’

‘How do we do that?’

‘We inundate Marcus Haliburton with requests for appointments under bogus names.’

‘That’s fun. I’ll tell the others.’