8,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Salt

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

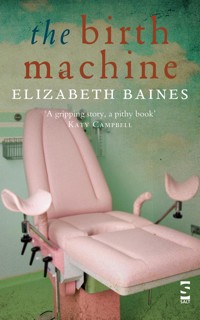

Tucked up on the ward and secure in the latest technology, Zelda is about to give birth to her baby. But things don't go to plan, and as her labour progresses and the drugs take over, Zelda enters a surreal world. Here, past and present become confused and blend with fairytale and myth. Old secrets surface and finally give birth to disturbing revelations in the present. Originally published in the eighties, The Birth Machine was seized on by readers as giving voice to a female experience absent from fiction until then and quickly became a classic text. Out of print for some years, The Birth Machine is now reissued in a revised version. It is still relevant today to modern Obstetrics and Medicine, however it is more than that: it is also a gripping story of buried secrets and a long-ago murder, and of present-day betrayals. Above all, it is a powerful novel about the ways we can wield control through logic and language, and about the battle over who owns the right to knowledge and to tell the stories of who we are. The book was dramatised for Radio 4 and starred Barbara Marten as Zelda.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

The Birth Machine

Tucked up on the ward and secure in the latest technology, Zelda is about to give birth to her baby. But things don’t go to plan, and as her labour progresses and the drugs take over, Zelda enters a surreal world. Here, past and present become confused and blend with fairytale and myth. Old secrets surface and finally give birth to disturbing revelations in the present.

Originally published in the eighties, The Birth Machine was seized on by readers as giving voice to a female experience absent from fiction until then and quickly became a classic text. Out of print for some years, The Birth Machine is now reissued in a revised version. It is still relevant today to modern Obstetrics and Medicine, however it is more than that: it is also a gripping story of buried secrets and a long-ago murder, and of present-day betrayals. Above all, it is a powerful novel about the ways we can wield control through logic and language, and about the battle over who owns the right to knowledge and to tell the stories of who we are. The book was dramatised for Radio 4 and starred Barbara Marten as Zelda.

Praise for Elizabeth Baines

‘The first well-crafted and surreal novel from a talented new writer.’ Literary Review

‘In many ways this novel is the birth myth of our age’ Janet Madden Simpson, In Dublin

‘Elizabeth Baines has a wry humour and satirical edge’ Martin Nicholls, City Life

‘A gripping story, a pithy book.’ Katy Campbell, City Limits

The Birth Machine

Elizabeth Baines was born in South Wales and lives in Manchester. She has been a teacher and is an occasional actor as well as the prize-winning author of plays for radio and stage, and of two novels, The Birth Machine and Body Cuts. Her award-winning short stories have been published widely in magazines and anthologies. Her first story collection, Balancing on the Edge of the World, was published by Salt in 2007. A novel, Too Many Magpies, will come from Salt in November 2009.

Also by Elizabeth Baines

Balancing on the Edge of the World (Salt, 2007)

Too Many Magpies (Salt, 2009)

The Birth Machine (Salt, 2010,2013)

Published by Salt Publishing Ltd

12 Norwich Road, Cromer, Norfolk NR27 0AX

All rights reserved

Copyright © Elizabeth Baines, 2010, 2013

The right of Elizabeth Baines to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Salt Publishing.

First published by The Women’s Press 1983

Second revised edition published by Starling Editions 1996

Third further revised edition Salt Publishing 2010

This electronic edition 2013

Created by Salt Publishing Ltd

This book is sold subject to the conditions that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

ISBN 978 1 84471 797 2 electronic

to my family

Once upon a time there lived a king and queen who had no children; and this they lamented very much. But one day as the queen was walking by the side of the river, a little fish lifted its head out of the water, and said, ‘Your wish shall be fulfilled, and you shall soon have a daughter.’

Rose-Bud, the classic 1823 English version by Edgar Taylor of Grimms’ fable, Dornröschen or Briar-Rose

Contents

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-one

Twenty-two

Twenty-three

Author’s Note

One

Ladies and Gentlemen: the age of the machine.

Ladies and Gentlemen, we are proud to welcome to Boston Professor McGuirk, who has flown in from England to lecture today on the latest developments in the use of the machine.

The audience ripples. What a little guy he is. They can’t see much without craning: the candyfloss tuft on his head, his gob-stopper eyeballs, lips like a twist of half-blown bubble gum. Somehow everyone expects a man of greater stature. He’s a little man with a big idea. He raises his hands to quell the applause, spreading fingers like blood-specked corner-shop sausages.

When the lecture’s over, will he stay for dinner? No, a taxi’s waiting to take him to the airport. Back home in England his supper will be keeping warm. His wife will rescue the soup while he opens the mail: another invitation to speak; his wife will lift the phone to cancel yet another dinner-party engagement. That’s the Professor; you’re lucky to catch him, sometimes he’s late, sometimes he’s gone already when you get there; often he regrets he can’t be there in any case.

His wife pours his cornflakes while he flicks through his diary. A tight schedule today. A teaching round to begin with.

‘Oh isn’t it today, dear, you have your rather special patient?’

‘Who’s that, dear?’ He’s taking salt with his egg. He puts the salt cellar back under the medical journal and his own latest article on the use of the machine.

‘Damn!’ He drops his spoon in annoyance. On the third line down a printing error seriously distorts the latest findings of McGuirk et al.

‘Oh, your shirt, dear.’

‘Damn the fools! What’s the point of proofreading if they can still make mistakes like this in the end?’

‘More coffee, dear? Everyone will understand, I’m sure. They’ll see from the tables.’

‘That’s not the point. I ask you – in a context where accuracy is the prime consideration!’

‘Your Dr Harris, dear, isn’t it today that his wife is being admitted?’

Backlogs of paperwork and last-minute emergencies: in the end he’s late. The students coagulate, kicking their heels in the corridor outside Ward Flora Bundy. Inside the ward the patient is prepared. The machine glistens ready. Where is he, they’re all waiting, where’s the Professor?

He’s here – a fire door bursts open. ‘Good morning, everyone, follow me, please, today we will demonstrate the use of the machine.’ The students fall in and stream off behind him, jostling, not quite catching him (doesn’t he get along fast for a little man?); he enters the ward and ducks into the first single room. The students fix round him like white corpuscles.

‘This machine will revolutionise care on these wards. Please note that in fact what we are using here is not one machine, but two. One for controlling the drug flow, another for monitoring the progress of the patient.’

Two machines wink and glisten.

The Professor swizzles and faces the students: ‘The technological leap consists in combining the two. Kindly dwell on this one moment: most medical advances have turned on just that kind of creative connection, on just that kind of leap of the creative imagination.’ He waits while they dwell on it.

‘This technique (ladies and gentlemen) can revolutionise lives.

‘Good morning, Mrs Harris. Mrs Harris is about to benefit from our modern technology. Aren’t we, Mrs Harris?’ He says with a wink in Mrs Harris’s direction: ‘Mrs Harris is a rather special patient. How are we feeling, Mrs Harris?’

He turns back to the students: ‘Now to connect the patient up to the machine.’

Are the students alert, can they catch the Professor’s eye, flat blue keystone to success and qualification? Sister sets the drip up. Now take the arm of the patient. Mrs Harris’s fingers are trembling just a little. What’s she got to be afraid of? The Professor, professionally distant, as indeed he ought to be, nonetheless looks up and flicks another little message: Mrs Harris, above anyone, must know she’s in good hands. It’ll only be a prick. Flick a germ-free needle out of its sterile plastipak container. Find a suitable vein.

The Professor pauses.

‘Nurse, could we have a tourniquet? Mrs Harris doesn’t seem to have good veins.’

The nurse squeezes tight. The arm below the tourniquet is growing puffed and waxy. No, these veins are not at all prominent.

Everyone waits. The students wonder if they ought to feel anxious. This patient is a rather special patient. This patient doesn’t have good veins.

‘There. That didn’t hurt, did it?’

The students relax. The patient is now attached to the machine. Press the ‘On’ switch; turn a button to adjust a finger on the dial. A measured amount of the drug begins to pass down the plastic tube towards the bloodstream. Place the electrodes on the two key sites on the patient’s abdomen. Everything is now under control. The nurse smooths the sheet. The Professor makes a nod of professional satisfaction with a little hint of social civility, and turns away to talk to the students.

The staff nurse advises: ‘Just lie back, Mrs Harris. When’s your husband coming?’ – over her shoulder, as she checks on everything, her pale hands hovering.

‘Soon,’ says Mrs Harris.

Soon.

Soon, they’re telling each other up in the Centre for Medical Research, where for two hours every morning Dr Roland Harris conducts his experiments with oestrogen implants:

‘Roland’s late.’

‘Isn’t this the day his wife is going to have a baby?’

‘Oh, blimey. Not today, of all days. Why didn’t he tell us? The day set aside for the final bloods! Are you sure? Perhaps he’s stuck in a traffic jam, the roads are up all over the city.’

The roads are up all over the city; the Victorian sewers are giving up beneath them. Ladies and Gentlemen: the age of skyscraper hospitals humming with technology above cities that crumble into the sewers.

Everything’s calm. The teaching group has moved on. The nursing staff are changing over. Sister reports: Single Ward Number Fourteen. Patient Four-Five-Oh. Just arrived for induction. Mrs Zelda Harris. Harris. Special name. Special patient. The nurses grimace, and move on to the next name.

Mrs Harris lies back. A plate-glass view of the sky. Sunlight wells along the walls and makes pools on the floor. At the side of the bed, the machine hums faintly. The sky outside reels. The room floats, suspended, between the four walls.

The new Sister on duty pops her head round. Mrs Harris has her eyes closed. Is she asleep? Is she dreaming?

She opens them and looks straight back.

‘That’s right, Mrs Harris, have a sleep, you’ll need it, that’s a good girl.’