Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Spurbuchverlag

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

THE BOY FROM AUSCHWITZ PETER HÖUENBEINER- THE SINTO WHO WAS ALSO A JEW This is the obituary written for a man who first had his concentration camp number removed and decades ater had it tattooed back in - with an apparentiv small but in terms of meaning huge change: instead of the letter Z, which was burned into the fourvearold boy in the Auschwitz concentration camp be bad an artfully curved " j endraved into his left forearm in Januarv 2015. According to the orally transmitted family narrative, Peter's mother's grandmother was Jewish, a born "Levi". This was also reported by his siblings. Peter Höllenreiner had survived the concentration cams Auschwitz Ravensbrick Mauthausen and Bergen-Belsen. Having escaped hell. he returned to his native cit of Munich in 1945 at the age of six. His school vears beain and the world meets him as if nothing had happened "In the back in the last rewI' was the school motto The eyclusion continued Peter Höllenreiner and his family had been subiected to National Socialist persecution as so-called "Gvosies" Despite democracv, a new form of government and the declaration of human rights - the old preiudices remained. And Peter lived in the country of the former perpetrators. it is his home!

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 268

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Maria Anna Willer

Der Junge aus Auschwitz

the boy from auschwitz

Maria Anna Willer

peter höllenreiner

Der Junge aus Auschwitz

the boy from auschwitz

Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek

Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der

Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische

Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.dnb.de abrufbar.

Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek

The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the

Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available

on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de.

1. print run 2023

Publication by © Spurbuchverlag

Am Eichenhügel 4, 96148 Baunach, Germany

www.spurbuch.de

ISBN 978 3 88778 838 4

eISBN 978 3 88778 938 1

Translation: Barbara Schulz

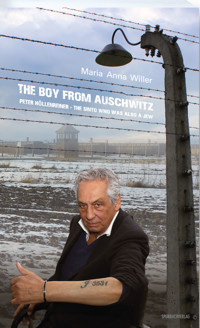

The photo of Peter Höllenreiner on the cover was taken by:

Federación Maranatha de Asociaciones Gitanas; taken at the VI Seminario

Internacional Rroma in Valencia, 2016.

table of contents

Message from Dieter Reiter lord mayor of Munich,

the state capital of Bavaria

........................................................................................7

It’s impossible to tell...

A childhood in captivity

..........................................................................................19

An elegant appearance

..............................................................................................11

The gypsy sticks in their minds

............................................................................33

I am not staying in this country

............................................................................99

Just one wish: being heard as a human being

..............................................107

I was never treated justly

........................................................................................45

First address

...................................................................................................................55

The second genocide

..................................................................................................65

A sinto and a jew

........................................................................................................111

The picture

....................................................................................................................125

Pile of files in the district court

.............................................................................73

How does man turn into a sinto, woman into a sintesa?

..........................85

Compensation files Sophie and Josef Höllenreiner

...................................129

Compensation files Manfred Höllenreiner

....................................................133

Compensation files Rosemarie Höllenreiner

................................................143

Compensation files Emma Höllenreiner

.........................................................149

The history of Sinti and Roma in Germany

....................................................153

Peter Höllenreiner’s Vita

.........................................................................................161

7

MESSAGE FROM

DIETER REITER

LORD MAYOR OF MUNICH,

THE STATE CAPITAL OF BAVARIA

Peter Höllenreiner was born in 1939 into a Sinti family in Munich. The family lived in the district Giesing, in Deisenhofener Straße, and was rooted firmly in the city until the National Socialists’ racist politics de-stroyed his former life. Almost four-year-old Peter, his parents and five brothers and sisters were segregated and persecuted as „Gypsies“, ar-rested in March 1943 and deported from Munich into the „Gypsy camp“ of Auschwitz-Birkenau. Peter survived despite inhumane conditions in various concentration camps and returned into his home town after the liberation of 1945. The physical and psychical wounds, however, remained.

After the war old prejudices and discriminations continued to live. Sin-ti and Roma were recognized as victims of persecution only to a limit-ed extent. An appropriate compensation for the injustice suffered was omitted. After an extended fight of the Sinti and Roman civil rights movement only did the story of persecution finally reach public aware-ness and was recognized as genocide by the Federal government in 1982.

Peter Höllenreiner, who died in July 2020, succeeded in holding his ground and building a prosperous life despite continuous discrimina-tion and much opposition. He remained closely attached to his home town Munich. In this book he broke his silence after decades and for the first time talked about his life in front of a wider public. As a survi-vor he contributed an important part to keeping alive the memory of in-justice suffered. Peter Höllenreiner deserves gratefulness for this feat.

The examination of the persecution of Sinti and Roma as well as of the continuing social resentments, prejudices and stereotypes is a task that is faced up by the state capital of Munich. It results in our personal special responsibility for present and future.

It is in this spirit that I hope for many interested readers of this book.

Dieter Reiter

Lord Mayor of Munich,

the State capital of Bavaria

8

PREFACE BY

ERICH SCHNEEBERGER

PRESIDENT OF THE ASSOCIATION OF GERMAN SINTI AND ROMA -

STATE ASSOCIATION OF BAVARIA

9

we owe thanks to Mrs. Maria Anna Willer for her empathic and sensi-tive description of Mr. Peter Höllenreiner’s report of persecution.

Survivors like Peter Höllenreiner carry the cultural inheritance, lan-guage and history of Sinti and Roma, who – according to National So-cialist race ideology – should have been extinguished for good. This is how this book will become not only an important contemporary docu-ment on the National Socialist genocide of Sinti and Roma but on the discrimination of our people in post-war Germany, too – and last but not least on the matter of indemnification.

Erich Schneeberger

President of the Association of German Sinti and Roma –

Regional Association of Bavaria

10

Peter Höllenreiner talking to journalists. In 2016 he returned for the first time to the place of horror of his childhood. As a contemporary witness, he takes part in the International Commemoration of the Murder of Sinti:zze and Rom:nja on 2 August 1944. Photo taken at the Auschwitz-Birkenau International Memorial, Oświęcim. Photo: Paskowski, Roberto.

11

AN ELEGANT APPEARANCE

Autumn 2012. You have to have a look at this highly built man. Peo-ple in the small village cannot help turning around to look at him when he walks along the row of houses on the kerb. Black suit, tanned skin, his greying hair combed backwards. He looks ahead of himself, then looks around and again into the distance ahead. His suit fits him per-fectly, his black shoes shine under the pleated trousers. An elegant ap-pearance. Too elegant in a village in Upper Bavaria, where only bank employees will wear a suit and a tie. And he does not even wear a tie. His white collar shows somewhat casually under his buttoned-up waist-coat. The topmost button remains open.

I am driving along the main road, I, too, have to have a look at him. Some days later he sits in my office. The modern condominium for elderly people was finished shortly before and I am the contact person in the liaison office for everybody who will be moving into a flat or is already living there. They are elderly people who live independently but want to have the security of a contact person at the same time, as-sistance and nursing service if necessary. Here he is sitting and telling me that he will move into one of the flats, the tenancy agreement just being signed. His landlord sent him as he had to sign a health care and attendance service contract to be able to move into the condominium. I liked him but at the same time I was wary. He did not ask any ques-tions. Nobody had ever signed a paper that quickly during those past four months that I had been working in this position. He was not inter-ested in the clauses. Where do you want me to sign?, was the second sentence after saying hello. 60.00 €flat rate for care and attendance service per month? Yes, yes, this is my banking card – you can take the details of my account – standing order – no problem.

He then tells vividly from the time when he lived in this valley. His arms are waving around. He once saved the life of an old farmer. His eyes had already stood out, he pulled him out of the river at the last second and saved him from drowning. I see the pictures drastically in front of me; he describes the scene that figuratively in his broad Ba-varian dialect: a mountain brook, deep potholes, that’s what the places are called where cold, normally peacefully rippling water masses are collecting in the depth, where big rocks form the bottom instead of soft-ly rounded stones. So, that’s where the old man had fallen into, was gasping for breath in the vortex and only kept swallowing water. The flailing arms don’t find anything to hold unto until his long arm grabs him and snatches him away from the deadly pull. The limp body lies on the river bank. He pushes onto the stomach. Like a fountain the water

12

boy of auschwitz

shoots out of the mouth, he breathes again. We both laugh and I do not know whether more about the fact that the farmer survived or the way he tells the story.

And then – the voice gets louder: They always screwed me in my life! I am not told why, what for, I don’t want to know either right then. I side track, deviate, ask about his severe handicap. Two slipped disks, 100 % disability. If ever he is going to be a case for nursing care he is going to throw himself off the balcony. No, you are not going to, I tell him, you will push the emergency button. We will install the house emergency call as soon as you have your telephone connection.

A few weeks later. He has moved into his flat, he is sitting opposite me at the same table in the office. He stretches out his hand, turns around his arm, pushes back the dark blue jacket until his forarm is visible, turns up the fine material until he reaches the inner side of his elbow, there, where the skin is white-pale and almost transparent. I had it removed. That was the number., he says. There are no num-bers to be seen but small green dots in a row. He quickly rolls down the sleeve again. Nothing but the golden wrist watch is shining with its many small dials under the fine flannel material. I am baffled. The man shows success, money, aesthetics. And now this. The randomly arrayed dots seem to have erred on his forearm.

When I was a child I have been in the concentration camp for three years, he says and almost as an explanation he adds. My mother was a Jew, my maternal grandmother, too.He utters the sentences quickly. His father’s family stems from Regensburg dating back to the 15thcen-tury. He shows me his family crest. His father should have got a divorce, but did not have it. He continues. We all ended up in the concentration camp. 39 of my family members perished there. My mother told me the most awful things. Surgeons put dogs into the wombs of pregnant women. It was much worse than it is shown today. Journalists always want me to tell them but I do not want to remember.

His eyes light up as I tell him that I find it almost impossible to be-lieve that I face him here as a fairly healthy person and a stately man after he had to live through all this. O, I did not get that much, I was a small child then, he waves my comment aside.

There is no longer uncertainty to hear in his voice, only outrage. It is getting louder. His neighbor denounced him, he said. Suddenly there was the police in front of his door. Now I am feeling faint. Then, today? What time is he referring to?, I wonder. It is quickly clear, the incident happened yesterday only. He was supposed to have carried off a child,

13

a girl into his newly moved in flat here. That is what the anonymously filed charges claimed. And it had only been his grandson to whom he showed his new flat. They had been to the playground together, then went to have an icecream, strolled through the village and finally went into the flat. Suddenly there were two policemen in front of his door. He was able to explain the situation to the officers. They immediately understood. But the shock! This shock! That will remain.

It was probably this inexpressible shock that made him talk about his past. Somewhat as a proof he showed the tatoo. He is panicky, he might not be believed. Panicky that the injustice and lack of rights that he had to witness as a child would overwhelm him again. We have coffee from paper cups that we have fetched from the bakery nextdoors or rather he brought it for my colleague and myself. Our office is a makeshift.

Rumors are at their best in the condominium. Some people saw the policemen in uniform in front of his door. The neighbor reassures the caretaker and probably a lot of other people that she did not file the charges against him. Nobody is responsible. And it does no longer matter who it was: The mischief is done. The police were there because of him, that is sufficient. I am frightened if he lives here.That is what I hear from some. He is a friendly person., others say. We want to live here in peace., I hear from still others.

Where is his wife?, my boss asks when I tell him about the incidents. Is she supposed to help him? Was that what he meant? He, too, seems to be helpless and concerned. He did not know about the past in the KZ. He knew him from former times when he lived in the village for a couple of years. And suddenly he was gone, my boss says, behind barred windows as the saying goes. I ask why. He looks out of the win-dow. Well, Persian carpets, gold trade, tax evasion perhaps, nobody knows for certain.And now he is back again, our Gypsy Peter.Gypsy Peter. I hear it for the first time. That’s what he was called in the village.

Later he will forbid me to use the word Gypsy. And still later he will learn that some in the village refer to him as the Gypsy Baron today and will laugh about it.

The police came again - this time in plain clothes – and asked where to find his flat. He personally shows up in my office later. His former partner is missing, he says, they asked him about her whereabouts. But what business of his is it. He wonders. He left her and does not know where she is. His flat in Munich is cleared. And: He took several thousand Euro in his wallet when moving, wanted to pay them into an account here. Wallet and contents disappeared when he took petrol,

AN ELEGANT APPEARANCE

14

boy of auschwitz

stolen, he was quite sure about that and he made a report. The officers, however, treated him like the accused person at the petrol station, ac-cording to him.

Meanwhile he moved out of the condominium and got married again. I write to him that I would write the story of his life if he wants me to. He calls me. I am pleased because he agrees. I had hoped for it but did not count on it. He often said he did not want to be reminded of his past, he did not want to talk about it. Now he consents to meeting me, he is allowing me to taperecord our conversations and he is going to decide in the course of our meetings whether a book will be the result of them.

I am still surprised at myself that I offered to do this. I was curious. I did not know then that the story of his life would fascinate me, that I, almost like in the water of the mountain brook, would be carried away and only find my peace once his story would be put to paper in words. In outlines I felt the incredible horrors of his childhood and could make the connection with his present life. I wanted to understand why he who had been exposed to a yearlong threat of his life as a child, he who had to suffer that much injustice had to justify himself again today. I wanted to know whether he was telling me the truth. I could not believe some of it. For example that he only touched a small pension of about 400 euro as a compensation for three years of detention in concentra-tion camps, for a childhood in permanent danger to life. I wondered how he was able to survive this time and come to terms with it. What gave him hope ad courage in his life? And I wondered how he was faring here in his home country today, the country that he was born in, that he spent almost all his life in and that had brought about that much suffering to him and his family.

Approximately ten years ago I lived through a similar situation. An old man was talking about his past as a holocaust survivor, just like that. I was supervising a workshop in creative writing of biographies for very elderly people. Mr. B. had surfaced suddenly at one of the meetings. The word Buchenwald happened to be mentioned and he was overcome by tears. He had survived that concentration camp as a child. He cried. He, too, showed the tatoo on his arm. Almost as a proof. His daughter talked to me afterwards. It was the first and only time that her father had talked about his childhood in the concentration camp. She gave me his telephone number. She would have liked me to stay in touch with him. But I did not have the time then to go to Munich regularly. And I knew: If I started it would take time for long talks. His doctor had said it was no good for him to be reminded. I left it at that. But I decided to take the time if ever a holocaust survivor would

15

be willing to entrust me with the story of his life. If I were given this trust again I would be appreciative of it and treat it as a big treasure. Anybody having survived this hell of inhumanity as a child to me is like a living miracle. I may have wanted to participate in this miracle.

Every biography is just an approximation of a person and the story of his life. As a biographer I try to understand, to fathom it and hand on tesserae. There is no impartial biography. A picture comes into be-ing that is filtered by the eyes, the observance of the biographer. This picture might look completely different. That is why I decided not to hide behind an invisible, supposedly anonymous writer but to show the process of this biography’s query.

The conversations are taperecorded. This way I make sure not to miss anything and can render reports by excerpts. There is one sad but true fact: I become the revisor of the life memories told by him. I am looking for established facts that will prove his reports, black on white. I go into the archives and turn over old files.

Our first meeting takes place on 05/28/2013 in his new flat. He is still living in the village, only few meters from his last flat. The words are pouring from him, some sentences end abruptly and tail in new sub-jects. Without waiting for a question he tells1:

I was born in 1939 in Munich in Deisenhofener Straße 64. We are six children, I was the youngest. My father was drafted to the Wehrmacht (German Armed Forces from 1935 – 1945), I was approx six months old then. My father was a German. My grandfather was a German, too. I’ll tell you the entire lineage later. He had to go to the military, the Wehr-macht, and returned home for a visit in 1942. This is all from hearsay because I cannot recall exactly. I was three years old. When my father came home, there was a certain Mr. Wutz, who recorded those docu-ments, where one came from and so on. And my mother happened to be a Jew, born Levi. “Well, ...“, my father just entered. “Well, what is go-ing on here?“ “I have to do that, Sepp, officially, I have to know where your wife comes from.“ Now I learnt that my mother was a Jew. “Well, how can you do, well, how can you, this...“ And my father took him and threw him out (…) He immediately had to join some such fighting unit in the military.

One day a lorry came, that took us all along. My mother and the six of us children. They took us to Ettstraße, that is the police station, we

1 In this book the writing in italics renders the direct speech of the author and some individual other persons. Any further speakers are individually mentioned or are recognizable in the context. If there is no speaker mentioned the phrases in italics are quotations by Peter Höllenreiner.

AN ELEGANT APPEARANCE

16

boy of auschwitz

stayed there for some days in a prison cell. We then got out of there and had to get onto a train. Those were freight wagons that you use to transport animals. Now I would have to lie to you. I don’t know which camp we got into first. The camps were Auschwitz, Ravensbrück, Mauthausen, Bergen-Belsen. There were four different camps and Auschwitz was the extermination camp, more or less. That’s where they were sent only for burning. That must have been the middle of 1942 – or, I cannot tell exactly – my father and my mother never talked about it, only what leaked through. They did not want it...

Then my father was dismissed from the military, because he did not get a divorce. He was supposed to get a divorce. He did not get it. That’s why they sent him into the camp we were in. He came to Auschwitz, but was in the Wehrmacht. Since he belonged to the Wehrmacht he was the block leader – had a functionary position in our block – that’s what it was termed. The person responsible for cleanliness and so on, that everything is in order. Well, my father got out of the military and virtually was with us. That was more or less our chance of survival, as my father was a member of the Wehrmacht.2

Do you recollect the deportation as a three-year old one?, I ask.

No, I don’t recollect anything. I only remember that I, after we had been released, when I was older, when there was a train coming, when I had to go to the train track and – ch, ch, ch – I always got frightened.

Did you cry?

No, I was terribly frightened. I had such feelings of anxiety. I – that was after the camp – I then, I don’t know for how long, I sweated and sweated during the night. And I always thought, my mother was no longer there. And kept crying during the night. My Mama kept taking me. „Boy, what is the matter?“ - I never told anything.

2 In the contemporary witness’s memory, personal observations meet selective memory, reports of family members as well as patterns of interpretation and explanation of events that are not to be explained by human standards. Memories may therefore deter from historical facts. The story that his father should have got a divorce and came only later into the camp, eg, does not correspond with the entries in the concentration camp admission lists. An explanation for the contemporary witness’s personal memory who then was a child of four years might have been that his father was less present than his mother.

17

View of the wooden baracks in camp section BII in concentration camp Birkenau

photo: Archive of the State Museum Auschwitz-Birkenau in Oświęcim.

AN ELEGANT APPEARANCE

19

IT’S IMPOSSIBLE TO TELL...

A CHILDHOOD IN CAPTIVITY

I am called Peter. My mother watched a movie during the time she was pregnant with me. It was about a Hungarian freedom fighter, he was called Janoschek. And she said: »My son is called Janoschek.« But we were not allowed to mention this name. I am called Peter, but my mother always called me »Janoschek«. That was her desire. But my sister, my brothers, they all called me »Hamster«. Hamster?, I ask (he laughs). I may have been three perhaps, had plump cheeks. And they said: »He looks like a small hamster.« And the name stuck. Well,...

The last snow flakes are falling. They are dancing, floating through the air one by one. You cannot see them any more on the hard tarmac, wet puddles of water are covering the ground. A young woman takes her seat on the horse-drawn vehicle, an infant covered in a blanket in her arms. The man places her suitcase into the loading area, he vaults onto the coach box with pride. He has fathered another child. A slight pull on the reins and the brown gelding moves through the streets of Munich. Mama is back again!is the welcoming shout when they reach home. A small wooden house, there is a fire going in the hearth. Hand him to me! I want to carry him!They all want to hold the small bundle in their arms. The grandfather comes, too, and Uncle Peter, Konrad, Babest, Aunt Notschga and Loni with her children. Everybody wants to

Memorial Place Auschwitz-Birkenau in 2016, only the foundations of the wooden prisoner barracks in camp section BII are still visible.

Picture: Paskowski, Roberto

20

boy of auschwitz

see him, the small Peter. Emma, his oldest sister, puts him into the care-fully prepared willow basket. The ten-year old one knows how to rest the small head in the crook of her arm and how to shelter the small bun-dle with it. She is rocking him gently. Why isn’t he called Janoschek?, Manfred calls. He is just coming home from school. You were saying he would be called Janoschek. I like that name much more.He doesn’t let up. That is no German name, we are not allowed to take it, they said. But for us he will remain our Janoschek, she says firmly.

This is how it might have been. I invented this scene. Before writing it I asked Peter Höllenreiner what he thought about how his mother had come home after the delivery in the Mai clinic. Whether his father had picked her up with his horse-drawn vehicle? No, he would not, he in-terrupts me gruffly. How far is the clinic situated from Deisenhofener Straße? That should be three, four kilometers, he guesses. I insist. Did she perhaps take the streetcar? No, if at all, she would have walked. But four kilometers? I stop short. Maybe with the drawbar trailer... He does not finish his sentence, changes the topic. There are no nice child-hood memories for him.

His father owned a forwarding company, his mother was 34 when she gave birth to her sixth child on 03/17/1939 in the Mai clinic in Munich. His siblings Emma, called Frieda, Manfred, Hugo, Rosemarie and Ringo were living with their parents in the Munich district of Giesing. His father’s brothers, too, lived there with their families, just like the grand-father. Peter knew his grandmother only from hearsay, she had died shortly before his birth. The Deisenhofener Straße, where their house was situated, was surrounded by meadows. The family had moved from Frankonia to Munich in the 1920es. They traded in horses, took over forwarding services, for the neighbouring margerine company, too. His grandfather owned a puppet theatre. He gave performances in Munich schools with it and travelled cross-country. He loved playing the violin and the street organ, but Peter recalls that only faintly.

21

These are his older brother Hugo’s memories1. There are no memo-ries of a happy childhood for Peter, he was too small to have kept them in his memory when they were still in existence.

According to the ideology and the plans of the then governing Na-tional Socialists the small boy did not have the right to live. At the time of his birth his death and that of his relations was a fait accom-pli on paper. The harbingers of the genocide had been there before his birth. 400 Sinti were deported into the KZ (Konzentrationslager - concentration camp) Dachau in 1936, in January 1938 the first Sinti and Roma were admitted to the concentration camps Buchenwald and Ravensbrück, at that time based on Himmler’s decree on so-called »ar-beitsscheue Elemente« (work-shy subjects). In December 1939 Himmler wrote a circular decree on the »Bekämpfung der Zigeunerplage« (exter-mination of the Gypsy pest) and in it asked for an »endgültige Lösung« (final solution) that had to be the result from »the character of this race«.2In the Nürnberg Race Laws three years before Sinti and Roma had been put on a par with the Jews in respect to the legal treatment as a »außereuropäische Fremdrasse« (Non-European Foreign Race).

IT’S IMPOSSIBLE TO TELL...

A CHILDHOOD IN CAPTIVITY

Peter Höllenreiner in his mother’s arms and with his brothers and sisters, picture approx 1942.

Picture: Documentation and Cultural Center of German Sinti and Roma, Heidelberg

1 see: Tuckermann, Anja: »Denk nicht, wir bleiben hier!« Die Lebensgeschichte des Sinto Hugo Höllenreiner. München, (4. Aufl.) 2013.

2 Tuckermann 2013, P. 295

22

boy of auschwitz

When in September 1939 the German Wehrmacht invades Poland Pe-ter’s father Josef Höllenreiner and four of his brothers are drafted to the military service. They have to hand over their seven horses to the German Reich for warfare, they are expropriated and disowned of their livelihood. The family try to protect themselves by a removal of mother and the six children to the countryside of Lenggries.