6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

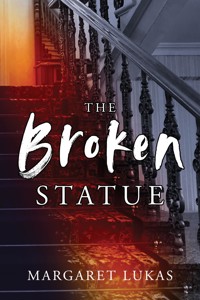

- Herausgeber: BQB Publishing

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Omaha, 1905: During the gilded age, when women live subjugated to men, eighteen-year-old Bridget prides herself on having earned acceptance to medical school.

When her father is murdered, a crime that does not interest the law because he was half Native American, she risks her plans to become a doctor, determined to avenge his murder.

Bridget's quest thrusts her into a world of seedy men and glitzy women in one of Omaha's most opulent brothels. There, she finds herself the prey rather than the hunter.

If she is to survive, she must keep the reclusive madam's shocking secrets, learn to trust her heart's yearning for the man who befriends her, and embrace her complicated alliance with a community of notorious women considered society's lowest.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

The Broken Statue: Book 2 in the River Women series

© 2021 Margaret Lukas. All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, digital, photocopying, or recording, except for the inclusion in a review, without permission in writing from the publisher.

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, names, incidents, organizations, and dialogue in this novel are either the products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

Published in the United States by BQB Publishing

(an imprint of Boutique of Quality Books Publishing Company)

www.bqbpublishing.com

978-1-952782-23-7 (p)

978-1-952782-24-4 (e)

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021941928

Book design by Robin Krauss, www.bookformatters.com

Cover design by Rebecca Lown, www.rebeccalowndesign.com

First editor: Olivia Swenson

Second editor: Andrea Vande Vorde

Praise for The Broken Statue and Margaret Lukas

“More than a tale of murder and vengeance, The Broken Statue is one visionary woman’s quest for justice that leads her on a harrowing journey to darker truths, and ultimately to love. A wild read.”

– Debra Magpie Earling, author of Perma Red

“Margaret Lukas’s The Broken Statue is a crime story and romance wrapped in a gritty portrayal of early 20th-century Omaha’s darker side. Lukas’s historical sensibilities are finely tuned, her characters individually etched, her sense of dialogue pitch-perfect. She captures the banter that both disguises and conveys deep feeling as well as any writer I know. I loved her complex and sorrowful portrayal of Plum Cake, a brothel madam, whose journey down a simple set of steps toward redemption is a marvel of harrowing tension and suspense. At all its multiple levels, this is an intriguing and serious novel that makes us re-think our history and our prejudices.

– Kent Meyers, author of Twisted Tree

“A skillfully written novel, The Broken Statue, is a swift-moving thoroughly enjoyable tale that offers insights into the often-overlooked lives of the women of the frontier. Lukas’s characters, many marginalized by race or circumstance, fairly get up and walk off the page into your heart.”

– Karen Gettert Shoemaker, author, The Meaning of Names, Winner One Book One Nebraska Award.

“In The Broken Statue, Margaret Lukas continues the story of Bridget Wright-Leonard of River People, now eighteen and with her heart set on medical school. Instead, Bridget wakes up one morning to a murdered father and a stolen horse. Determined to get to the bottom of the crime, Bridget pursues the murderer to Omaha and quickly finds herself caught up in the complex world of an upscale brothel. With evocative prose, an engaging plot, and well-drawn characters, Lukas celebrates the resiliency and sisterhood of early 20th century mid-Western women, while casting an insightful and feminist eye on historic—and timely—issues of domestic violence, disenfranchisement, and racial injustice towards indigenous people.”

– Erica C. Witsell, author of Give

“In The Broken Statue Margaret Lukas gives us a spellbinding look into the lawless gilded age; a world full of suspense, murder, prostitution, and redemption.

– Jeff Kurrus, editor, Nebraskaland Magazine, author of Can You Dance Like John

To Jackson, Sofia, Lukas, Molly, Stefan, Colin, and Owen

One

1905

The world drifted.

Beyond the old farmhouse window light crested in the east, spreading a glittering sheen over the foot of new snow. Tall grasses lay blown over and buried, trees hung laden, and the fence posts running down the lane looked as if each held a round, fat hen.

Bridget clutched her cup. At eighteen, she’d already lived in Nebraska for several years, had seen many quiet and beautiful January mornings. So why was her stomach jittery and the coffee she held quivering?

Behind her, logs burned in the stove and Papa Henry sat at the table finishing his breakfast, his third coffee refill. He pushed back his plate and rose. Wire, on his three legs, came from beneath the table, his tail wagging.

“It looks cold out there,” Bridget said. “Shall I run and grab you an extra shirt?”

Papa took his coat from a peg by the back door, palmed his floppy leather hat, and pushed it low, covering the tops of his brown ears. He was a giant of a man to Bridget, though with his gently sloping shoulders and back, she’d grown nearly as tall.

“Nebraska’s always freezing,” he said. His eyes, surrounded by crinkled and leathered skin, smiled. “Least when it ain’t hotter than Hades.”

“The roads will be closed. Dr. Potter won’t be taking his buggy out. I could help you in the barn and walk into town an hour or two late.”

He nodded at her books on the table. “You got your work right there. Take my chores and I’m staring at a day of boredom.”

“I could help hang the new barn door.”

“Nah. Facing’s rotted, need to tear that off. We’ll wait for a warmer day.”

She moved from the front-facing window to the back, watched dog and man trek through the snow. At seventy-four, Papa Henry was stubborn and content to remain so. He didn’t have much time for the bother of people, white or red, and he saw no need to change his ways. He loved her fiercely, though sometimes that love scared him, and Bridget could feel the tightness in his chest clutch in her own. He’d loved his wife and son, but he’d lost them both. Now she, the daughter he’d adopted and loved, was all he had left. How could he not fear losing her too?

She continued watching the pair, Papa Henry with his long white braids hanging down the back of his dark coat, scuffling in tracks for Wire’s use. She dismissed a sudden tugging at the back of her throat. He was aging, but he could still steady a plow behind a team of workhorses, pull fence, chop wood, muck the cattle barn, harvest.

Man and loping dog rounded the corner of the barn and disappeared, but in Bridget’s mind, she saw Papa Henry stop at the double-wide doors, check that the long two-by-four he used as a buttress was tight, keeping the old door with its rotting hinges secure. He’d open the smaller side door only wide enough for them to slide through, and then pull it shut again, conserving as much heat as possible for the animals inside. He believed himself the brother of his horses. His four-horse team, their large, thick bodies and muscular legs, bred for labor rather than speed; and his two spotted horses, Smoke and a mare named Luna-Blue. In the spring, there’d be a spotted foal.

For Papa Henry, his horses, his dog, and his land sufficed for all the “churching” he needed.

Bridget sipped her cooling coffee. The breakfast dishes needed washing, and she planned to study before heading into town, but she couldn’t pull herself from the blue-gray luminous light and the shadows the farm buildings threw over the snow. There were two barns. The second, three stories tall, Papa Henry used for carpentry. He’d built an ark there, a project he’d toiled on for years. Now he worked around the great vessel making coffins for grieving families who couldn’t afford newfangled, factory-produced boxes. Or families who believed those caskets disrespected their dead. Folks preferring simple wood.

She looked past the barns and through a thin growth of trees several yards beyond to the silver band of the Missouri River. A stag appeared, having walked out of the water, or from between trees, she wasn’t certain. She smiled. A second animal surprised her more. A third and then a fourth splashed coffee over her cup rim. A single male deer in mid-January, running across a pasture or along the road with a still-unshed rack, was rare. Though even then, she’d never seen a deer with such a large crown of antlers. Never seen one approach so close to the buildings. And never had she seen four seemingly conjured out of thin air.

She set her trembling cup on the sill.

The first animal reached the side of the carpentry barn and stopped. One by one, the others joined him, and then waited for the one behind. When they stood four abreast, they started for her. Their eyes fixed, aiming.

She sucked in a breath, held it burning in her lungs.

High stepping through the snow, they crossed the wide yard for the house, keeping their precise formation. Shoulder to shoulder, they might have been harnessed to an unseen sleigh. Guided by reins under supernatural control.

She dared not move. She wished for Papa Henry, even Wire to bark and prove he saw the impossible too.

She’d believed the animals fully formed, but as they continued coming, their bodies thickened, chests expanded, copper coats deepened, antlers swelled and swept to the height of elk crests.

Breathing was hard, backing away from the window, impossible. Her knees trembled against the insides of her worn dungarees. The animals held her as if they’d thrown out a line, roped, and tethered her soul. What otherworld prompting had sent them?

The closer the deer came, the more quartered she felt. Each stag taking his acre. They continued, hoofs punching through the snow, not stopping until they reached the window. The pools of their eyes locked on her. Eyes deeper than human eyes. Containers of deeper stories.

She found herself nodding, sure they’d come to be seen, recognized. “Yes. I see you,” she whispered, though she had no idea what they meant her to take from the encounter.

The stags blinked, their legs stiffened, and their tails shot up. Startled as if from deer dreams, they turned, the white undersides of their tails flashing. In a series of leaps and bird-like swoops, they half-flew back toward the trees and river. Vanished.

Bridget’s mouth felt full of dust, her bones brittle. The animals had wrung the moisture from her, leaving her suddenly ancient. They’d also left behind darkness that made her turn and look over her shoulder. A gloom waited for her somewhere close: on the stoop just outside, under the table where Wire slept, in the next cupboard she opened.

With unsteady hands, she began stacking the breakfast dishes, coaxing her heart to settle. “Nera, Nera.” The words she’d so often used as a child. Wanting to summon the will of young Nera, who in Irish legend gathered the courage to save her people by facing the most frightful thing in her world: a red-eyed skeleton hanging in a tree. And doing the most frightful thing: stealing a fingerbone from the fiend.

“Stop,” Bridget scolded herself. She wouldn’t let a few deer scare her. She was grown now and would start medical school in the fall. That good fortune was incredible enough to warrant a visit from stags. They’d probably come to tell her not to worry, that she could easily make the grade and measure up to the males in her class. She knew that already.

She forced her mind off the deer and onto the day, weeks earlier, when Papa Henry returned from town with the letter from the board of admissions. As she’d torn open the envelope, he’d taken a chair at the table. Staying so close, she imagined that if she crumbled on reading a rejection, he meant to be there to catch her.

The interview with the board had not gone smoothly. The requirements for entry were a high school diploma, a command of the English language, and a strong moral character with a reference confirming the fact. She had the diploma and her six-page essay proved both her intelligence and command of the language. It was the third requirement—despite a glowing letter from Dr. Potter—that made the committee frown. She lived with an Indian.

“A savage,” the board president had said, his eyes nearly rolling back to white.

“A young female,” this from the jowled, paunchy man farther down the table, “with a female temperament.” The last two words haughty with accusation.

“Unchaperoned,” another said.

She’d kept her tongue, not fired back in Papa Henry’s defense. Even now, weeks later, that silence continued to shame her. Afraid of rebuttal, she’d let the wind of their hate speech blow and what they assumed was Papa Henry’s low morality go unchallenged. She’d taken her cues from two men who sat quietly but for their gentle reminders that since opening in 1880, the school had kept with the progressive model of admitting a few qualified women each year. Should such individuals present themselves. If they were to admit her, that would raise the number of females in the freshmen class to an impressive three among the nearly fifty males.

“Accepted on a probationary basis,” the formal letter read, going on to say she must throughout the course of study “prove herself exceptional and above moral reproach.”

She’d described the interview to Papa Henry in detail but not mentioned the board’s disapproval of her living arrangements. She felt certain he believed all acceptance letters contained probationary conditions.

“I’m in,” she’d cried, wrapping her arms around his neck. “I’m in.”

Neither of them felt threatened by the restrictions. Of course, she’d act above moral reproach. And without question, she would excel academically. She would fulfill her dream of becoming a doctor.

When Papa Henry stepped back into the house two hours later, Bridget had not yet washed the dishes. She closed her book and waited as Wire tried to shake snow off his back and landed on his legless hip, then worked himself back onto his three legs. She waited as Papa Henry removed his coat and hung the thick wool on its peg. She waited as he palmed his large hat from his head onto hers, something he’d done affectionately every day for the six years he’d been her father.

“You’ll never believe what happened.” She hugged his hat as she crossed to hang it with his coat.

She told him about the deer and watched his white brows lift. “They were larger than deer,” she stressed. “I’m sure they were tricksters.”

He poured himself a cup of coffee and sat. “Some folks can walk into a thin stand of trees and get lost. Others walk into forests and find themselves.”

That sort of talk—a hundred things implied in the subtext—usually made her smile, but the volume in the animals’ eyes and how they’d left her hollowed out haunted her. “The deer?”

He shrugged. “They didn’t come to me. What do you think?”

“You interpret things all the time.” She cut a slice of bread from a loaf on the table, used it like a rag to wipe grease from the frying pan. “A beetle turns around twice, and you’re changing all your plans for the day.” She leaned down to Wire, and when he’d licked her cheek, she rewarded him with the bread.

“Beetles visit me. The deer visited you.” Though he seemed to refuse her, his eyes held an uneasy concern. “What do you feel they said?”

“I’m not sure.”

He waited.

“I don’t know.”

He leaned back in his chair, his cup swallowed in his brown hands. “Nature acting different than it does: fish in trees, rain falling up, stags in foursomes. They are messengers.”

A chill clawed across her shoulders. “Messengers?” Even though she’d felt the same, coming from Papa Henry the word increased her foreboding. “Can that be a good thing?”

“Could.”

She thought of the animals’ march forward, the winter sun striking their endless antler points, the fur on their pole legs, each foreleg lifting from the snow and striking down again, soundless. Even through the window she’d smelled their musk and the trees and the river they’d just left. The closer they’d come, the deeper that coming pierced.

Picking up her anatomy book, she hesitated, set it down again. What if she’d been wrong? Imagined the whole event or fallen asleep on her feet and had some kind of weird, waking dream. She wasn’t getting enough sleep, studying into the late hours, and only two days previously, she’d spent dawn to dawn with Dr. Potter at the bedside of a baby dying from pertussis, the horrid sound of the toddler gasping for air after each coughing spell, sending the mother into a new fit of weeping.

She didn’t have to get all mystical over deer, digging into her Irish heritage full of fairies and harpies, or into Papa Henry’s Omaha Indian culture full of tricksters and animal spirit-guides. Deer were deer, and that was that.

She hoped.

Two

The walk into Bleaksville took Bridget longer than usual. Even in places where the wind had cleared the road, she refused to hurry. The first flush of mystery and disquiet from her sighting had eased, and she walked through a world lit with beauty. Snow and ice thickened even the smallest nibs on trees, grasses waved icy seed heads, and the fields lay in sprays of crystal.

Dr. Potter, in his mid-eighties, sat behind his desk. He’d been in and out of retirement a couple of times as younger doctors came to Bleaksville but left after a year or two, seeking larger practices in larger towns.

“Top of the morning.” He added something of a nod and a pleasant enough grunt and returned to his task—comparing her ledger notes to those he’d written on a patient’s card. A practice he enjoyed on slow days when no appointments pressed for his time and he’d caught up with his medical journals. He jotted corrections to her observations or expanded on her details in the margins she kept clean for him. More than once, she’d seen him add a notation to his records after reading hers.

She’d come to him the summer before with a stack of her anatomy drawings, hoping to so impress him with her knowledge and determination to get into medical school that he’d take her under his wing. If she proved herself, wouldn’t he then write a recommendation? She’d arrived just as he was crawling into his buggy to visit a family with four little ones and the mother in labor again. He settled on the buggy seat as if every bone in his body protested.

“I’m too old for this,” he said, looking down at her youth. “Get in. We’ll talk on the way.”

Now these months later, she’d yet to miss a day, and he’d come to rely on her. And slowly, so had the town, happy for her willing hands and the aid she gave Dr. Potter.

She hung her coat and hat, remembering Dr. Potter’s reaction when she told him of her probationary acceptance to medical school. His bushy gray brows came together as he took the letter with a frown and rapped the sheet with a thick finger. Then he picked up his pen and circled the word acceptance so many times the ink marked through the word probationary. “Congratulations. This town is going to have a fine doctor.”

The office door burst open. “Doctor!” Timmy Fester smelled of cold and fear. He wore a coat he’d not wasted time buttoning and was hatless. His nose and ears were red, tears streamed down his face. “It’s Ma. She’s hurt bad.”

Dr. Potter rose with a catch in his hip. “Tell her we’re coming.”

Bridget grabbed one of his old gray sweaters from the coat rack, draped it over Timmy’s head, and tied the sleeves under his chin. She reached for her own coat, Dr. Potter’s bag, and hurried after the boy.

“Tell her don’t move,” Dr. Potter called after them. Bridget paused for any further instructions, but he shooed her. “Go on, hurry.”

Catching up to Timmy, she knew her assignment: cover the four blocks to the Fester house as quickly as possible. She could run, keep up with ten-year-old Timmy, stand over Mrs. Fester, and make sure she received no additional injuries before Dr. Potter arrived. When they were called to farmsteads outside of town, she went to his barn, hitched his old nag to his even older buggy, and brought the trap around to the office. The Festers lived close. A distance covered faster on foot.

Mrs. Fester sat slumped on a chair by the stove. She moaned, cradling her arm and rocking in pain.

Bridget knew something of the Festers’ story. Years of failed crops, a tornado that finally sucked away their last bit of hope, taking the house, barn, and windmill. Forcing them into Bleaksville, carrying only the few salvaged items they’d dug out of the mud, and into an abandoned house on the edge of town.

Mr. Fester, a man Bridget had met on another occasion when Timmy came crying for help, hovered close to his wife. His eyes were glassy. “She fell down the stairs. The woman can’t stay on her feet.”

Bridget dropped to Mrs. Fester’s side—a young woman not a full decade older than herself. “Dr. Potter is on his way. He’ll be here soon. I’m not leaving you.” She lifted glowering eyes to Mr. Fester. “I’m not going anywhere.”

Nearly three hours later, Bridget and Dr. Potter made their slow way back over unshoveled streets. Mrs. Fester’s arm had been broken. After being sure the bone lined up correctly, Bridget had helped Dr. Potter wind on strips of plaster-soaked gauze. All the while, Mr. Fester paced.

When they’d finished, they helped her into Timmy’s room and left her in a well-sedated sleep. With Dr. Potter repacking his bag in the kitchen, Bridget stayed in the bedroom to pull the boy from beneath his bed, hold him a moment, and promise his mother would be all right. She helped him make a pallet on the floor where he was to sleep the next week and gave him two grownup jobs. The first was keeping the secret he could only share with his mother: the bottle of pain medicine Dr. Potter was leaving. And the second, very grownup responsibility was to run back to the office if his mother’s arm began to hurt too much. This was his assignment, Bridget told him, because his mother would not think her pain was worth bothering Dr. Potter.

Now as they walked through the snow, Bridget fought down her anger. “It’s awful. That man’s a monster.” Dr. Potter hadn’t asked Mrs. Fester what happened, nor had he threatened Mr. Fester. “He’s got to be stopped.” There were no laws against a man’s treatment of his wife, no matter how callous. And neither the sheriff—absent from town for a month or more—nor the acting sheriff, Mr. Thayer, would involve themselves in the matter. But Dr. Potter? “Someone has to speak up, make that man stop.”

Dr. Potter’s cane left a trail of pecked holes in the crusty surface. “It isn’t time.”

“Last time wasn’t ‘the time’ either. When will it be ‘the time’?”

“I brung that man into the world. Watched him grow up. A good boy.”

When Dr. Potter agreed to let Bridget work as his assistant, she’d made a solemn promise to him: She would not offer any medical opinion in the presence of a patient. However, they were alone now.

“You’re the most respected man in Bleaksville. If you aren’t going to speak up, who will?”

He watched his footing for slick patches. “If I had accused him, what of the next time? Suppose she suffers another broken bone, or worse, and he refuses my help? She needs to know I’ll always come.”

He was scolding her, she felt it, but the tragedy she’d witnessed gripped her. He was a compassionate man. That, she’d never doubt. Still. “You could do something.”

“What do you suggest?”

They covered a full block in silence.

“Anger won’t serve your patients,” he said. “Judging neither. Nearly every case you’ll see is the result of human folly. Diseases because of overindulgence, accidents because of carelessness. Hatred, anger, drunkenness. Take your pick. You plan to curse every patient? Or you plan to try and help?”

The question was rhetorical, and the only answer, silence.

They’d reached Main Street again. Bleaksville looked as idyllic as a snowy-roofed Currier and Ives Christmas card. For the Festers, the reality was vastly different.

Dr. Potter lifted his gaze from the snowy scene to Bridget. “Keep your eye on your medicine.”

A brilliant doctor, he’d never been subtle with her. She admired him and owed him for his strong letter of recommendation and the invaluable medical training she received working with him. That didn’t help Mrs. Fester. The woman needed more than a kindly old doctor. She needed laws. Dr. Potter was aging, growing weak physically and in spirit. When she had her license and the authority that came with it, she’d call out wrongs.

Bridget took the steps to the hayloft. The temperature outside had dropped further with the setting sun and even inside the barn she could see her breath and that of the animals. Still, the solid walls kept out the wind that ripped and tore the air outside. Though she rarely helped with the morning chores, she only missed the evening ones when she worked late with Dr. Potter. After a day of tending wounds and putting mustard packs on wheezing children’s chests, feeding horses and running a hand over their powerful shoulders and haunches was her own hour of church. She pitched hay down into the long trough for Papa Henry’s team, then crossed the mow to use the fork again and throw down for Luna-Blue and Smoke. Chaff fluttered in the lantern light like flakes of gold, but the sight didn’t brighten her mood.

Finishing her task, she came out of the loft and took up the iron curry brush. She couldn’t bathe Smoke—or any horse—in winter, but she brushed him in firm circular motions to loosen dead hair, and then used long strokes to rid it from the coat.

Across the barn, Papa Henry sat perched on his milking stool, his two braids swaying as he worked. He gave her sidelong glances but left her to her fretting. He knew she’d returned from Dr. Potter’s troubled, and he knew she was sworn never to discuss patients outside of the office.

Mrs. Fester is in so much pain, Bridget wanted to say. It’s wrong. She finished Smoke’s grooming and laid the brush along the top railing of his stall. She held his cheeks and stared into his large, dark eyes. He blinked, his long lashes going down and up. His breath was rhythmic, wheaty, and warm. Deepening and steadying her own.

“There was a woman today,” she told him, loud enough for Papa Henry to hear. Even omitting Mrs. Fester’s name, she knew she crossed a line. “A broken arm. Her pain was awful. Her husband was at least partially responsible. She did everything she could to keep from screaming. Her little boy was there, watching.”

With the cow securely in its stanchion, Papa Henry’s hands worked two teats, a rhythmic spurt-spurt as milk gushed into his pail, froth rising. A line of cats stood close, waiting for the moment he’d turn a cow’s nipple and squirt warm milk into each mouth.

“Once again, nothing will be done.” Bridget choked back emotion. “Her eyes were empty. Like she looked into the future and saw only more hopelessness.”

“Dr. Potter?” he asked.

“He thinks I’m too emotional. Too impatient.”

“A warrior must learn patience. He must grow the power to let an enemy he cannot defeat pass. He must learn to wait, let the buffalo come close and the hunters get in place before he shoots.”

“Oh, Papa.” She gave Smoke a final pat and stepped out of the horse’s stall. “You should have been raised on the prairie with Indian chiefs instead of on this farm.”

“I read books, and my mother taught me about her people. I know a young warrior without patience must stay in camp until he is wise. Until he does not desire fame but that his people eat through the winter.”

“You and Dr. Potter. When I’m a doctor …”

When I’m a doctor had become her mantra, the final thought on any discussion that ended without resolution. The phrase pleased Papa Henry as much as it did her, and pride passed over his eyes every time she said it.

Later, Papa Henry closed his journal and readied for bed, adding logs to the kitchen stove and to the hearth in their sitting room where Bridget studied. He dropped a hand on her shoulder, kept it there, brown and strong. “You get a good night’s sleep. No need to push yourself so hard.”

She patted his hand. “You worry too much. Only a couple of hours more.”

She watched him climb the stairs, Wire on his heels. Having Papa Henry for a father made her rich. The farmhouse was old, and their clothes were rough—shirts and dungarees with patched elbows and knees—but thick and warm. Their table had plenty of good food, planted and harvested by them. They had stories and dreams and love for each other. Though only seven years had passed since she’d said goodbye to dying Grandma Teegan and boarded a train with other orphans, or half-orphans, those younger years of starving in New York felt a lifetime ago.

She returned to her reading and note taking. This ledger Dr. Potter would never see. She consulted a diagram in the anatomy book he’d loaned her and copied it, changing the drawing to match how she imagined the bone in Mrs. Fester’s arm had looked. A thin arm, blotches of purple bruising, and a break across the humerus. She finished by writing detailed notes on Dr. Potter’s process for setting the break.

She dipped her pen, touched the rim of her inkbottle to remove the excess. In the morning, she’d go, with or without Dr. Potter, and check on Mrs. Fester. Give her a woman’s company. Until then, she and Timmy would hopefully have a comfortable night. Dr. Potter had left enough laudanum for pain.

An hour passed, two. Her head sagged, and she woke with a jerk. She turned out the kerosene lamp and climbed the stairs. When Papa Henry walked past her bedroom door a few minutes later, she’d changed into her nightclothes and crawled into bed with her eyes already closing.

“Where are you going?” she managed.

He stopped, looked into the dark room. “Horses are pacing.”

“In the barn?” Even speaking took effort. Wire stood at his side, and she was glad to see the dog there. “You sure?”

“Old men are light sleepers. I’ll see you in the morning.”

Her eyes closed. She thought to say, “Dress warm, be sure to grab your hat,” but she lacked the energy.

Three

Bridget woke the following morning with the sun not yet risen, but her window more charcoal than black. Her room frigid. She hesitated before leaving the warmth of her bed, then rushed to touch the stovepipe running up from the kitchen, through her floor, and venting out her ceiling. Cold. Mornings normally called Papa Henry, and he went down in the predawn to build up the fires. As the stove warmed the kitchen, the rising heat warmed her room. But not today.

She pulled on britches—a pair with only a single patched knee—and two flannel shirts. The now-empty hangers swung beside her only skirt. She’d need a few more for attending classes in the fall. Pants might be seen as unseemly attire for a female student and threaten her probationary status.

Before stepping into the hall, she stopped at her dresser and ran her hand down the sleeve of hanging red calico. Grandma Teegan’s braid was tucked carefully inside, and touching the talisman a morning ritual. She gave her own hair a couple of brushstrokes, twisted it into a sloppy braid, and pinned that to cover the narrow scar running over the crown of her head.

From her end of the hall, she couldn’t see inside Papa Henry’s room, only that his door was open, proving he still slept. Given his late-night tramp to the barn and his age, he’d earned a morning of sleeping in. She headed downstairs.

They had a system for conserving heat in the house. At night, they both left their bedroom doors open, Papa Henry to receive warmth rising from the living room hearth, and she to share the warmth from the stovepipe in her room. During the day, Papa Henry kept his door closed to keep as much warmth as possible from being drawn into his north-facing room and out the old windows. Of the three upstairs bedrooms, his was the coldest. Still, he preferred that room. From there, with the soft glow of the moon lighting the yard, he could peer out over the paddock, checking periodically for the yellow eyes of circling wolves.

Alone in the dark kitchen, Bridget shivered again, struck a match, touched it to the cord wick of a lantern, and replaced the glass shade. She couldn’t see more than a couple of feet past the window, but she knew yesterday’s snowdrifts still whorled across the yard and the country roads. Too high for buggy passage. For the second day, Dr. Potter would remain in town. Only an emergency would make him saddle his horse, use a stool, hoist himself into that saddle, and ride out to give assistance. Thankfully, no women were scheduled to deliver for a few weeks and no old men wheezed alone and needed a tonic or the touch of a supportive hand. However, illnesses and accidents—even so-called accidents like Mrs. Fester’s—didn’t stay away because of snow.

Kindling filled a box by the back door. A second box held the short logs Papa Henry had measured and cut to fit the stove’s firebox. Using the iron poker, she lifted the metal plate, added sticks, laying them crosshatched to allow for draw, then logs.

With the fire burning, she pumped water for the kettle and set it on the heat. Rubbing her chilly hands together, she eyed the eggs sitting on the counter. When Papa Henry walked into the kitchen, felt the stove’s warmth, saw eggs cooking, and smelled coffee boiling, his kind eyes would twinkle and a smile would spread across his wizened face.

Folks in town likely thought them an odd family—elderly Papa Henry with his dark skin, white hair, and half-Indian blood, and she with her poppy-colored hair, pale skin, and Irish blood. But a twelve-year-old girl with no one else, and a kind man with no one else also constituted a family. A judge believed so too, and put his signature on adoption papers. Henry Leonard became her legal father, though for the year previous, he’d already been the father by every measure. She’d always call him Papa Henry, not just Papa, the single word too close to Pappy, the man who’d abandoned her to Grandma Teegan in Ireland and taken away Mum.

Lifting eggs from the basket, Bridget hesitated at how cold and heavy they felt. She didn’t usually handle them first thing in the morning and never in a kitchen so cold. She shuddered suddenly, remembering the deer she’d seen the previous morning.

“Don’t be silly,” she whispered to herself. “Those deer didn’t mean a thing.”

From a can of lard, mostly bacon drippings, she spooned out a small dollop and dropped it into her frying pan. When the grease popped, she cracked in two eggs, the whites bubbling around the edges and turning golden. Tipping the pan to pool the hot grease in the lower curve, she spooned it over the tops of the yolks. The skin whitened just the way Papa Henry liked.

She took a long look through the door into the living room and to the stairs she’d used half an hour earlier. Though she tried to deny her growing unease, the knot tightened in her stomach. She slid the eggs onto a plate and dropped two slices of bread into the pan for grilling.

With everything done and the morning light brighter, she listened. No sound came from overhead, no weight creaked boards there or strained the stairs. She approached the barn-facing window, this time looking over the backyard. Only muffled tracks. Footprints half erased by the night’s wind and a dusting of new snow. Papa Henry had not risen before her and gone to the barn.

Her heart kicked. Wire? Even if the cold and a late night caused Papa Henry to sleep in, where was Wire? He ought to be sitting at her feet, his tail rapping the floor, his eyes begging for food.

She forced herself to walk, not run, through the sitting room and past the cold ashes in the fireplace. The absence of a single red ember meant Papa Henry had not woken even once in the night to add logs.

The staircase, full of a new day’s promise when she’d come down, looked shadowed. “Papa Henry? Wire?”

The blankets on his bed were thrown back. His shoes gone. Wire too. Trying to wrestle her mind around what it might mean, she half stumbled back down the stairs. Her coat hung by the kitchen door; the hook where he hung his empty. She forced herself to slow and take deep breaths. Papa Henry would laugh at her fright, or possibly be saddened by the fact that even after six years under his roof, she still felt so insecure. For how many months after moving into his house had he needed to come into her room at night, wake her from the same sobbing nightmare, dry her tears, and assure her she was no longer alone?

“I’m here,” he said night after night. “Right down the hall.”

She stepped out, winter’s cold grabbing her. The barn looked half a mile away, not just across the yard. She followed the tracks she’d help carve deeper the night before. Crossing the windswept hoof prints of four deer, she nearly cried out remembering how they’d come to her.

She went on, running now. Just because she couldn’t think why Papa Henry might have spent the night in the barn didn’t mean there weren’t a dozen reasons. Had a skunk or coyote wedged its nose in somewhere, gained entrance to the barn, and upset the horses? The night had been so cold, Papa Henry would have come to the house periodically to warm himself, leaving evidence that he’d been there: melted snow inside the door from his galoshes, a cold coffee cup, and the fires built up.

Meeting a set of horse tracks made Bridget stop and look carefully. They’d been made hours earlier. One horse coming down the lane to the barn and two leaving. She breathed easier; someone must have come for Papa Henry, an emergency requiring his help. Though why would he not leave a note on the table or wake her to say he was going? And Wire?

The sight of the broken barn door, the gaping maw of it hanging on one hinge, and the lumber buttress on the ground, threatened to sink her to her knees. No emergency would cause Papa Henry to leave the door so carelessly open to wolves and winter.

Wire bounded out of the building’s shadows and jumped at Bridget’s chest. She caught him in a momentary flood of relief, but he squirmed away, whining and scuttling back inside. She followed at a slower pace. “Papa Henry?” In the dim light, they passed Smoke’s stall, the gate open and the horse gone. Farther on, Papa Henry’s hat lay on the floor. Bridget’s heart hammered. Wire whined for her to hurry.

Deeper still, the four-horse team huddled, their ears high, their tails tight against their rumps. She patted flanks, coaxed them to separate and let her through. Papa Henry lay facedown on the floor, two blood-soaked patches soiling the back of his coat. The hilt of his own knife sticking up from one.

Wire howled.

She dropped to the floor at Papa Henry’s side, leaned over him, disbelief and shock wracking her with uncertainty, her lips an inch from his cheek. Barely visible puffs of his breath lifted in the cold air. She thought to run for Dr. Potter but couldn’t make herself stand again. She needed to think, do the right thing, and do it immediately. Ought she pull out the knife, end the horror of seeing the blade in his back? Or would that open the wound more, cause more bleeding? Indecision screamed through her. Going for Dr. Potter and returning would take at least a half hour. Maybe twice as long by the time he dressed and saddled his horse. Suppose he wasn’t home but called off to treat a patient? For all those long minutes, she’d be away while Papa Henry needed her.

“I have to go for help.” Yes, she had to. “I’m going for Dr. Potter. Please, please don’t die.” She gripped his hand and cried out in anguish.

At the sound, Wire pushed into her lap, stood on his back leg, braced his front paws on her chest, and forced his head under her chin.

Papa Henry’s hand, which only the night before had lovingly grasped her shoulder, was ice cold.

She lowered the dead weight onto the floor and let Wire push her over. Lying beside her father’s body, she knew she’d not seen his breath. She’d seen her own breath bounce off his frozen cheek.

Papa Henry was gone.

Four

Sheriff Thayer dropped Papa Henry’s prized knife onto the kitchen table. Accusation in the sound of the weapon’s cold clang. Bridget flinched at the clatter, the knife still stained with traces of blood, though the smearing showed an effort had been made to wipe it clean in the snow.

Thayer tipped his head toward the knife. “That his?”

Wire sat on his haunches beside Bridget, his head against her thigh. She kept one hand on the dog’s neck, dug her fingers into the dog’s cowl, and managed to nod.

“You sure it’s his? It’s from wigwam days. Could belong to another redskin. You seen one of ’em hanging around? The law ain’t got no concern with what red does to red.”

She wanted the man gone. The entire morning—could it still be only morning?—was a murky swill. She’d ridden Gus, one of the horses in Papa Henry’s team, into town. She’d burst into Dr. Potter’s house screaming, found him struggling to get out of bed and pull on his pants before she reached his room. “Papa Henry’s been murdered!”

For a moment, disbelief had clouded the old man’s eyes. “Get the sheriff,” he’d said. “I’ll be along.”

In Thayer’s office, she’d screamed the same news but hadn’t waited to see him rise from his desk. Running out the door, she’d heard him call in the direction of the office’s two cells. “You boys slept off your drink? Looks like I need you.”

She’d left them to locate horses. She ran on, slipping in the snow to the rear of the mercantile and to her friend Cora living in the back with her husband.

“My God,” Cora had cried. “I’ll get my coat.”

She’d not sent her husband to the livery for her horse but climbed on the back of Gus. Bridget wondered now if Cora had done so not just to save time but so she could wrap her arms around Bridget and hold her through the ride back.

Now, Sheriff Thayer stood in the kitchen, glaring down, and Cora stood behind her, close as a hen ready to stretch out a wing. Dr. Potter, along with Thayer’s two men, hadn’t yet returned from the barn.

“You listening to me?” Sheriff Thayer’s voice a near shout. “You suppose that’s what happened? Another redskin knifed him?”

No, Bridget thought, and you don’t suppose it either. Thayer, who’d been acting sheriff for only two weeks, didn’t want to investigate. He likely had no idea where to begin, and the way he kept fiddling with the ends of his weak mustache bespoke his nervousness. Was it his fear of trying to arrest a murderer, or his fear of never finding him?

“It wasn’t an Indian,” Bridget said. “And it wasn’t just a knife. He was shot in the back too.”

Thayer pulled again on the end of his straggly mustache. “If this here is a redskin problem,” with a gloved finger, he pushed the knife an inch closer to Bridget, “then it ain’t mine. I’m beholden only to white. How you know this ain’t red?”

Bridget’s eyes burned. The horror of Papa Henry’s murder and the loss of him came at her like bursts of wind. She was rocked, raked, pushed back, then minutes later it subsided enough for her to scrub her face and gasp for steadying breaths. Before the horror gusted again.

She swallowed hard. Thayer’s badge, pinned to the front of his coat, looked dull as a flattened tin can. “It wasn’t an Indian. No Indian is stupid enough to leave behind such a valuable knife.”

He sucked at his top lip, exposing a gap in his front teeth. One tooth chipped, the remaining stub jutting at an angle. “The law’s got nothing to say about a dead redskin off the res.”

“Mr. Thayer,” Cora interrupted. “I think you’ve made that point abundantly clear, but a man has been killed. One of our own. It’s your job to find out who did it.”

Bridget couldn’t lift her eyes from the bloody knife hilt. She’d cried and screamed at seeing it in Papa Henry’s back, but at the moment, she felt empty, the knife’s lying there impossible. The first years of her life, she’d listened to Grandma Teegan’s admonishment to “fight death.” Papa Henry had not fought hard enough. He’d drawn a knife rather than a gun.

“As you well know,” Cora seemed to place each word as though carefully stacking a shelf at the mercantile, the better for Thayer to examine, “Henry was not off a reservation. He was born right here in this house. You went to school with his son.”

Thayer sniffed. “Ain’t any of those matters. We got us a sit-u-ashun here. There’s laws for whites. Chief being—”

“Henry,” Bridget cried. “If you can’t say Mr. Leonard, at least say Henry.”

“Was.” Thayer chuckled in Cora’s direction. “Was his name. Dead now.”

Bridget gripped harder at Wire’s cowl. “Whoever killed Papa Henry took Smoke.”

“Smoke?” His eyes narrowed.

She wanted to push him out the door, refuse to answer another question. “Our black-and-white-spotted stallion. You’ve seen him a thousand times.”

“Horse thieving? Redskins love horse thieving.”

“Mr. Thayer,” Cora said. “Please. Show some respect.”

He looked down at Bridget. “You got any proof a horse was stolen?”

A gale struck her. Wire whined at her clutching, and she moved her hand to his shoulder. “Smoke is gone. That’s your proof.”

“A feisty horse will run off given a chance. A barn door left open.”

Acting sheriff, Papa Henry had said of Thayer, only until there’s a proper election. Papa Henry hadn’t minded the man though, had thought someone interested only in his monthly pay was healthier for the town than someone walking the streets looking to make trouble.

“Smoke didn’t run off,” Bridget said. “Papa Henry was killed, his horse stolen.” Her voice broke. “The tracks. One set led to the barn. Then two sets came out. Side by side. Evenly spaced as train rails, the distance of a lead rope apart.” She watched the shadow pass over his expression. “You didn’t see them, did you? You and the two you brought out rode in right over the top of them.” So had she, kicking at Gus’s flanks, desperate to get help and return to the body.

“Oh, Bridget,” Cora said. “We rode over them too. We aren’t any of us experienced in crime scenes.”

Thayer shuffled, a wet, slushy sound coming from the floor where snow melted off his boots. “Hoof prints ain’t like a boot or a lady’s shoe. They don’t tell you a dang thing. You know anyone had an eye on that horse?”

Bridget shook her head.

He glanced again at Cora, his lip giving a single, determined twitch. “I’ll get to the bottom of Chief’s murder.”

Chief. Most of Bleaksville referred to Papa Henry as Chief. Even Bridget had before her adoption, before he explained all men have names to which they’re partial. Now, hearing others use the term hurt, reminding her of her own insensitivity and thoughtlessness. And making her think of Sheriff Cripe. The man Thayer replaced hadn’t much liked anyone in town, thought them all country hicks, but he’d hated Papa Henry most. His list of racist monikers had been long: half-breed, braid, blanket. And the name Bridget hated most: buck. Said with a gyration of his hips, intended to suggest an animal rutting.

“If Papa Henry were white,” she said, “you’d care about his death.”

He looked at her as if she’d suggested if dogs were kangaroos.

“It’s our country.” His gaze lifted to her red hair. “White race.”

The words cold and cutting. She’d heard the whispers, read the papers, and seen the cartoons. Negros, Jews, Chinese, Irish, Indians—all depicted in caricatures with features more animal than human.

“Cripe.” The name flew from her mouth. “Your boss. He’d do it. Cripe hated Papa Henry.”

Cora had gone to stare out the back window at the barn. She turned on hearing the name. “Mr. Thayer,” she said, “please. Bridget doesn’t know what she’s saying. A father’s death is a terrible thing.”

A bubble sputtered from the gap in Thayer’s teeth. “It ain’t lawmen need looking into.”

Cora squatted beside Bridget’s chair. “You don’t want to start accusing a man who could make trouble for you.”

“Cripe would do it.”

A man stuck his head just inside the door. “Freezing our balls out here.”

“I know Sheriff Cripe disliked Henry,” Cora tried again. “And I’ve never cared for the man, but he was elected. We need to respect that. Why, when he no longer has any contact with Henry, would he do something so awful? And Smoke is, what,” she tried to keep her voice soothing, “eight or nine years old? If Cripe wanted that horse, he’d have stolen him long ago. Sheriff Thayer has a point, this does look like someone traveling through, happening on your place. Though,” Cora looked pointedly at Thayer, “it’s highly unlikely that it was an Indian.”

Thayer touched his hat in Cora’s direction and started for the door. “I had the boys put Chief in one of ’em coffin boxes. Law says redskins can’t no longer hang their dead in trees or put ’em up on scaffolds. Civilized folks need them in the ground.”

Bridget watched Thayer’s wet tracks crossing the floor, the heels of his rundown boots, and the dirty hems of his trousers. The town’s acting sheriff. “Wait.” When he turned, she eyed him squarely. “Isn’t all murder against the law?”

He sucked his crooked tooth. “A trial’s needed to decide a man’s guilt. And that’d be a jury of white men, all of ’em remembering Custer and his fine soldiers.” He threw open the kitchen door to winter. “You best forget this here happened and study ’em there books. Cora done bragged to half the town how you figure on being a doctor.”

“You’re not leaving us alone?” Cora asked.

“Ain’t nothing else to be done here.”

“There’s a murderer out there.” She crossed her arms over her chest. “And tonight?”

He considered. “If I ain’t settled nothing, I’ll be back. Stay the night so you women can sleep. Keep ’em barn doors closed. Wolves’ll catch a scent. Ground thaws in the spring, you can hire yourself a grave digger.” He stepped out. “Body’s froze up good. It’ll keep.”

Five

For several long minutes, while wood crackled in the stove and a slow block of sunlight spread over the kitchen table, Bridget sat with Cora, her head on Cora’s shoulder. When she felt able, they pulled on their coats and walked arm in arm through the trampled snow back to the barn. They carried warm water and towels. Cora thought to grab a comb.

The body lay in a box Papa Henry had built himself. Seeing it there, Bridget couldn’t immediately cross the barn floor. She went to Luna-Blue milling nervously in her stall, the horse’s eyes showing too much white. The mare had heard the shots fired. She’d smelled the gunpowder, seen the stabbing, and watched Smoke being led away. She smelled Papa Henry’s blood even now and knew the body was there.

“It’s all right, girl.” Bridget stroked the long face, pushed back the white mane from Luna-Blue’s eyes. “Sherriff Thayer will find Smoke.” Would he?

She left the horse and dropped to her knees on the straw-littered floor beside the pine box. Thayer’s men hadn’t bothered to fit on a top, and Papa Henry’s gray eyes stared.

Cora knelt beside her.

“You’ve done this before?” Bridget asked. “Washed the dead?”

“It can be nice. The last moments with a person. When you are serving them.”

Bridget dipped a washcloth in the water and wiped Papa Henry’s cheeks. She’d kissed them countless times, but she’d never run an intimate hand over the wrinkled, leathered skin. She stopped and sank back on her heels. He was beautiful. The etchings on his face like the fine grains in wood or the ridges and veins in leaves. Only the sight of his staring eyes tore at her.

“His eyes,” she sobbed.

Cora reached to touch them closed, but the frozen lids remained open. She patted her coat pockets, then the pockets on her trouser skirt. “I haven’t a coin on me.” She sighed, held out a handkerchief. “Is this all right?”

Bridget nodded.

Carefully, solemnly, Cora draped the starched and pressed hankie with its lace trim over the dark and frozen face.

Bridget’s lungs heaved. The act felt like a burial. She reached behind Papa Henry’s neck to pull his braids forward and lay them over his chest. Only stubble.

“Cora,” she cried. “His braids are gone!”

“God save us! Why would someone?”

For trophies? Grief coursed through Bridget. With fresh horror, she noticed his hands were open, palms up. He’d frozen facedown, his fingers splayed. Turned over, his hands looked as if he wanted them held. His shoulders had been crammed into the box, and dirty boot prints soiled his coat front.

Wire leapt up at her gasp, stood on his hind leg just as he’d done earlier, and leaned into her. Luna-Blue whickered in her stall. At the edge of the haymow, two peering cats scurried off, knocking down loose bits of straw.

After Dr. Potter had finished his examination and returned to the house, Thayer’s men, Bridget knew, had put the body in a coffin. One that was too narrow. Rather than look for a larger box, they’d stomped on Papa Henry’s chest, breaking frozen joints.

“Don’t weep over it,” Cora said of Bridget’s furious brushing at the mud. “He’s at peace. Whoever did that hasn’t disrespected Henry, only himself.”

The minutes dragged into an hour. Bridget hated leaving the body again despite Cora’s coaxing. She relented only when they both shivered and even their gloved fingertips stung with cold.

Papa Henry’s knife still lay on the table. Afraid Cora meant to somehow dispose of it, or that Thayer might realize evidence should be secured and return for it, Bridget slid the blade into a drawer.

Cora added wood to the stove and in the rising warmth rubbed her cold hands together. “I’m afraid Thayer’s in over his head.”

“It’s not just that.” Bridget drew in a tight breath. “He doesn’t care. And he’s not going to question Cripe.”

“An investigation doesn’t need to begin and end with Thayer. A state marshal can be brought in.”

“How? Who decides that? Do we write the governor, and how long will that take? And when he hears Papa Henry was half Omaha Indian?”

“I don’t know.” Cora stopped rubbing her hands. “I’m only saying justice doesn’t begin and end with what Thayer decides.”

The eggs Bridget cooked earlier sat cold and rubbery on a plate. She picked one up by its crusty edge and held it out for Wire. Then the second, letting the dog lick the grease from her fingers. Papa Henry had saved Wire, fishing him out of the river after someone cruelly wrapped him in barbed wire and threw him in to drown.

“Did you know Papa Henry thought Cripe caused this?” She patted the stub off Wire’s hip.

Cora shuddered. “Cripe likely isn’t the only man around who’d toss a dog into the river.”

The morning before, Bridget had been in the Fester house. Though she hadn’t cursed Mr. Fester, her looks hadn’t been sweet. Had she so angered him? He’d suffered a host of hardships that were turning him into a mean and desperate man, but he wouldn’t steal and murder. Would he?

“Many men around here,” Cora went on, “could use the money a beautiful horse brought. Let’s see what Thayer does. If his investigation goes nowhere, or he does nothing, we’ll go over his head. I’ll do as you say and write to the governor.”

“And wait weeks for an answer.”

“Justice is more important than speed.”

“What if justice depends on speed? If even a few days pass, Smoke will be long gone. He needs to be found now, see who has him before he’s sold. Sold again and again, passing through a number of hands.”

Cora carried the plate Bridget had emptied to the sink and began to pump water. “I don’t like that look in your eyes. Let men handle it.”

“Even if they don’t care? Papa Henry would want Smoke brought home. And Cripe—”

“Henry would not want you running off looking for a horse and a murderer,” Cora said. “Think about your future.”

“I am.” She’d shamed herself by standing silently in front of the admissions board. She wouldn’t disrespect Papa Henry a second time. “I can’t live with myself if I do nothing.”

“Writing to higher authorities, insisting on a full investigation, isn’t nothing.”

Bridget held her tongue. Cora and her letters. Before Papa Henry adopted Bridget, Cora had written to newspapers in states west of Nebraska seeking any information on Bridget’s parents. A letter arrived from a stranger stating Kathleen and Darcy Wright had passed on. Died in Butte, Montana, of camp sickness. That information, Bridget knew—though Cora believed it like a Biblical truth—might easily be false. The letter writer may have heard about the camp’s sicknesses second-or third-hand, the story mangled with each retelling, names added, others only assumed dead. Or a case of mistaken identity, another couple from Ireland having died that harsh winter. Or the letter could have been an outright hoax. Bridget hadn’t seen a body or even a grave marker. With almost no memories of Pappy, it was easier to believe him dead. Believing it of Mum was another matter.

A letter could not confirm her parents’ death, and a letter would not find Papa Henry’s murderer.

Six

Dressed in her heaviest dungarees, Bridget paced in her cold room.

Thayer still snored on the sofa though the sun was nearly up. She didn’t want to go down and possibly wake him trying to sneak by. Didn’t want to see him at all, but she had work to do and a barn door to check. Yesterday morning, before Thayer arrived with the other two, Cora had helped Bridget work the large stone back underneath the sagging door, then wedge the two-by-four buttress into place. After a long, windy night, the door may have shivered off the stone, the cows needed milking, and the horses waited for feed and water.