6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: No Exit Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

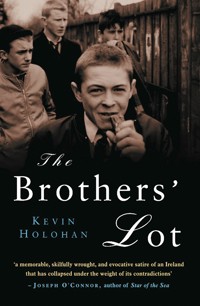

A hilarious and satirical debut novel exploring religious hypocrisy in an Irish grade school. Combining the spirit of Kingsley Amis's Lucky Jim with a bawdy evisceration of hypocrisy in old-school Catholic education, The Brothers' Lot is a comic satire that tells the story of the Brothers of Godly Coercion School for Young Boys of Meager Means, a dilapidated Dickensian institution run by an assemblage of eccentric, insane, and often nasty celibate Brothers. The school is in decline and the Brothers hunger for a miracle to move their founder, the Venerable Saorseach O'Rahilly, along the path to Sainthood. When a possible miracle presents itself, the Brothers fervently seize on it with the help of the ethically pliant Diocesan Investigator, himself hungry for a miracle to boost his career. The school simultaneously comes under threat from strange outside forces. The harder the Brothers try to defend the school, the worse things seem to get. It takes an outsider, Finbar Sullivan, a young student newly arrived at the school, to see that the source of the threat may in fact lie inside the school itself. As the miracle unravels, the Brothers' efforts to preserve it unleash a disastrous chain of events. Tackling a serious subject from the oblique viewpoint of satire, The Brothers' Lot explores the culture that allowed abuses within church-run institutions in Ireland to go unchecked for decades. The novel inhabits a space where Angela's Ashes meets the work of Flann O'Brien and Mervyn Peake, while providing a look at a regrettable era that still haunts many countries across the globe.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

‘Kevin Holohan’s wickedly funny debut novel, set in a rundown Dublin religious school where the spirits are low but the Gaelic pride runs high, will make you laugh almost as much as it makes you weep, for beyond their almost comical incompetence and a thin veneer of piety the Brothers who run the place are sad, flawed men, whose weaknesses range from sadism to depravity. They educate by cudgel and dole out discipline with a leather strap, while protagonist Finbar Sullivan and the other long-suffering students bear it all with the kind of wise-cracking cynicism, irreverence, and pranks that one would expect at that age.’

— Preston L. Allen, author of Jesus Boy

‘The Brothers’ Lot is a screamingly funny indictment of the culture of repression and abuse that has plagued Ireland for generations, but it is much more than that. It is a brilliantly told tale, compassionate and brutal. Most important, it celebrates the spirit of reckless bravery and rebellion, the spirit that draws back the curtain on iconic institutions to reveal the frailty of an ecclesiastical house of cards.’

— Tim McLoughlin, author of Heart of the Old Country

THE BROTHERS’ LOT

A NOVEL BY

KEVIN HOLOHAN

www.noexit.co.uk

For all the kids who never had a chance to answer back

Whatsoever you do unto the least of these my brethren, you do unto me.

—Matthew 25:40

Contents

PraiseTitle PageDedicationEpigraphPrologue1234567891011121314151617181920212223242526272829303132333435363738EpilogueAcknowledgmentsCopyright

Prologue

With a start Brother Boland woke. He had dozed off while praying at his cot. His coarse tweed undershirt was soaked in sweat. Around him pressed the deep silence of night.

He had been dreaming. He was flying through the air. He could see the school below him. He could hear a voice in the wind. It came from everywhere and nowhere and was filled with a strange harmony of anger, dust, and the smell of wood.

Brother Boland had started to circle lower over the school and suddenly, all lightness sucked from him, he began to fall toward the roof of the monastery. That was when he woke.

He got up off his knees and stared around the surrounding dark of his cell. Everything was as it had been for his last sixty years as a Brother. The statue of the Infant de Prague stood where it always had on the windowsill. His trousers hung on the chair as usual. His cassock hung on the back of the door as always like some outsized crow carcass. Everything was as it should be, yet not. Brother Boland could not put words on what it was, but there was something. He stepped into his slippers and threw on his cassock.

His slippers made a dead fish sound on the highly polished wooden floor as he tiptoed along. The half-lightfrom the street slid through the windows and cast shadows everywhere. From his perch in the return of the stairs, Venerable Saorseach O’Rahilly, the founder of the Brotherhood, seemed to cower uncertainly back into the shadows, so unlike his stern, disciplinarian, daylight demeanour. Brother Boland nodded and blessed himself as he passed the statue and wisped down the stairs to the ground floor like a tattered black fog with the shakes.

In the monastery kitchen he checked all the doors and windows. Locked tight all of them. He ghosted through the ground-floor Biology lab. All secure there. He paused and leaned a moment against one of the big desks.

Satisfied that all was safe downstairs, Brother Boland twitched back up the stairs as fast as he could. At the top landing he wrestled with the stiff, heavy door. He opened it with a jolt. His hand spidered its way over the musty wood of the inner stairs until it found the light switch. He flicked it. Nothing. The darkness inside seemed to intensify in retaliation against his attempt to dispel it.

The air stank of damp and neglect. The narrow spiral stairs protested under Brother Boland’s feet as he cautiously ascended. The air was chill yet oppressive and Brother Boland laboured to find enough oxygen to keep going.

The stairs led to another small landing. There Brother Boland paused and peered up into the gloom. He could just about make out the dull sheen of the bell above him. He paused, unsure whether to head up the ladder. He shivered. He brought his breathing to a minimum and listened. In the nearby flats a dog barked the bark of one who lives from dustbins. From closer came an answering howl hoping to reduce its desperate straits by sharing them. Such foolishness! He had not come all the way up here in the middle of the night to listen to dogs barking and speculate on how they found food!

He moved to the corner of the landing and reached down. His hands found the familiar boxy contours. This was his safe haven. This was where he came when the bad things closed in around him. This was his retreat.

Here he kept his tea chest. This was how he had arrived at the school: five months old, in the bottom of a tea chest with whatever clothes he owned thrown over him, left on the steps of the monastery by his unfortunate mother. There had been a note too, or so Brother Boland had been told, but that was long gone, as were the clothes. Yet he still had the tea chest, he still had his roots.

He sat on the edge of the chest and slowly rocked to and fro. He clutched each elbow and held himself close. As he felt his unease begin to subside, he reached out and ran his hands over the surface of the chest. He luxuriated in the familiarity of its shape and lovingly rubbed the rusted edging strips. His talonlike fingers felt love in the rough metal surface. He pressed at the tiny nail heads and sensed the love pulse into him. Brother Boland squeezed his eyes shut and ran his fingers faster over the metal edges of the box.

He emptied his mind. All he was aware of was the persistent tick-ticking of his middle finger on the side of the tea chest. He tried to listen behind that. There it was. There, just on the edge of the silence, was the sound of something different. Not new, but changed, differently evident. Boland shuddered. He felt a white light invade him but would not breathe for fear of putting the silence out of focus. He then felt a jolt as the silence slipped away from him. He tensed and twitched and with one final spasm he snapped into catatonic rigidity, unmoving as the walls around him.

When he woke the crows cawed harshly in the trees. The early trucks hauling toward the docks ground their gears like prophets’ teeth. Dogs barked their secret plans for the new day and softly the blinds and curtains of the early risers were drawn to admit the new dawn. In the early pubs, the dockers and the bona fides drank in uneasy alliance, all of them, either by choice or necessity, on a different timetable to the rest of the city. The tide shrugged out of the Liffey bringing in a cacophony of gulls to pick at the sludge in its shallows.

Brother Boland carefully placed his tea chest back in its corner and ran his hands lovingly over its surface. Whatever had haunted his night was gone. He glanced at his watch. He had two minutes to get to the bottom of the stairs and ring the bell for morning mass. He removed his slippers and tiptoed silently down the stairs.

1

Finbar! Declan! Wake up, boys! It’s time to get cracking!”

His mother’s voice drifted in from the fuzzy outskirts of Finbar’s dream. It registered in his head for a few moments and then faded back into the muffled waking world.

“Finbar! Get up, will you, for the love of God!”

It was closer now. From out of nowhere light leapt at his eyelids. He scrunched his eyes shut and felt the covers being pulled off. He clutched at them but they slid from his grip.

“Now, Finbar! I won’t tell you again! Lord knows I have enough to be doing! Come on, love, please …”

His mother’s voice trailed off and he finally opened his eyes. She was standing there at the end of his bed, biting the knuckle of her index finger and staring at the wall.

“All right, mam, all right. I’m up!” he said brightly, and swung himself into a sitting position on the side of the bed.

Mrs. Sullivan nodded and smiled weakly: “That’s a good boy. I’ll just get Declan up then.”

In the bathroom Finbar ran the water. Stone cold. He splashed it on his face. Outside he could hear them at it already.

“Declan! Get up!”

“Yeah, yeah, yeah.”

“Declan! I’m turning the light on now. Come on!”

“Yeah. Fine. Just leave me alone, will you?”

“Leave you alone, is it? Well, I’m sorry, Mr. High and Mighty, but you have to get up just like the rest of us. Finbar’s already up.”

“Well, isn’t he the little saint then?”

“Declan, that’s quite enough lip out of you. Just get up, can’t you?”

“I didn’t ask to go.”

“Not this again! Look, we’re going and that’s that. We’re not having this argument again. Now, get up out of that and stop your nonsense!”

“What if I don’t?”

“The movers will be here in half an hour.”

“Well, maybe I’ll get myself a flat then.”

“You will not! You don’t have two pennies to rub together. I’ll not have any more of this talk. We’ve heard enough of it out of you.”

Her voice was getting louder and shriller. Finbar sat on the toilet and ran the water in the sink as hard as it could go. He didn’t need to hear all this over again. There’d been weeks of it already and with each week Declan had become more disagreeable to the point where now he hardly spoke to anyone in the house, not even Finbar. All because that stupid Sheila Barry had dumped him or run away from home or whatever: no one was too clear on it.

“Yeah? And why not? I can do what I want!” yelled Declan.

“Not while you’re under my roof.”

“And who says I want to be under your roof? I didn’t ask to be part of this family. I didn’t ask to be born into this.”

“Oh, Sacred Heart of Jesus, Declan, stop it!”

Finbar heard the front door slam.

“What the hell is going on up there? Ye can be heard out on the street!” called his father from the bottom of the stairs.

“Nothing,” called Declan, the fire suddenly gone from his voice and replaced by a damp, leaden resignation.

“Well, fine then! Get up so! I got some sausages and bread from Mrs. Morrissey. Breakfast in ten minutes!” shouted Mr. Sullivan.

“Finbar, are you nearly finished in there? Declan has to wash himself,” called Mrs. Sullivan as she made her way back downstairs.

Finbar reached over and slowly turned off the water in the sink.

Once breakfast was over and the dishes washed, dried, and packed into the car, Finbar sat on the footpath outside the house and watched the movers load the furniture into the back of the truck. His father hovered around them, mostly getting in the way and making their job more difficult, but Jack Sullivan was not the type of man to trust hired workmen to do a good job unless he was breathing down their necks.

“Finbar! Give me a hand with these few things,” his mother called from the front door. He took the box of photographs and ornaments from her and put it in the car. Declan stormed out of the house full of gangly seventeen-year-old bad temper and flopped into the backseat of the car. He sat there with a face like a curse on him and glared out the window at nothing in particular.

Mr. Sullivan oversupervised the movers loading the dining table and then ran back into the house. Finbar went in after him. The house echoed weirdly under his footsteps. Even the lino was gone. It had so quickly turned from his home into a shell of brick and floorboards. He watched his father stand at the top of the stairs and stare ruefully out the small window at his garden below. He went out to the car and sat in the backseat beside the silent, fuming Declan. Separated only by three years, they might as well have been from different planets. Finbar couldn’t be bothered even trying to talk to him and picked his own patch of nothing in particular to stare at and sighed.

“Will ye stop that sighing like an old woman, ye little prick! Just cos you’re going to miss the first day of school. Stupid sap,” hissed Declan.

“Ah, get lost you,” answered Finbar.

Declan rolled down the window and spat onto the street.

“Right so!” called Mrs. Sullivan as she came out of the house and pulled the door behind her. Its familiar clunk followed by the little rattle of the knocker and the letter box jabbed at Finbar with little pins of “not going to hear that sound again, boi!” He clenched his teeth and stared away down the street.

Mr. Sullivan slid into the car and foostered around under the seat trying to move it back from the steering wheel. His brother Francie, whose car it was, was a much thinner man than he. “Stupid fecking thing!” he muttered, and then gave up. Mrs. Sullivan got into the car and settled herself with a tug at her skirt and another quick, hollowly cheery “Right so!”

As they headed across Cork to the Dublin Road, Finbar peered out the window at all the familiar sights. Off to Dublin! he thought with scorn. A scorn that, ironically, his parents had spent most of his early years inculcating in him. Why the hell were they now taking him from the Real True Capital of the Country all the way to Dirty Dublin where they knew no one? He didn’t want to leave Cork. It was stupid, that’s what it was. It was just fecking stupid and thick. “That’s the why and there’ll be no more talk about it!” was not a reason.

2

Jesus wept! Get away from the window, will you?” shouted Mr. Laverty, the French teacher, as he banged on the frosted staff room window where the two grey shadows were sitting. Reluctantly the two shapes moved away. “Desperate, isn’t it?” he lamented to the crowded but mostly silent staff room. He went to his bag, took out his thermos, and poured himself a quick cup of coffee, then lit a cigarette and stared dejectedly through the dirty glass at the sliver of cloudy sky visible above the monastery. He wrinkled his nose, and his droopy moustache and small rheumy eyes momentarily moved closer together. September already. Where did the summer go? It seemed only a few days ago that they had finished up, looking forward to the long, easy summer.

Now, gazing out through the grubby window, hemmed in by the growing noise of the boys outside and surrounded by the heavy tired sounds of all the other teachers in the staff room, it all seemed so desperately far away and long ago, like something that had happened in someone else’s life.

“Another year in this kip,” he moaned.

“Ah, feck off with ye now, Laverty. The last thing we need is your complaining to add to it,” chided Spud Murphy, the History teacher. Spud flashed a big, crooked, nicotine-stained grin and puffed on the pipe that he hoped would finally help him give up cigarettes this year. His mischievous eyes wrinkled mockingly at Laverty through the cloud of smoke.

“Piss off, Murphy,” snapped Laverty, and winced at the smell of the pipe.

Slowly all in the staff room became aware that it was getting loud, very loud, outside in the yard. The white noise of the boys’ voices seemed to be pressing against the windows like some incredibly heavy fog. It was a weighty, mirthless sound filled with the hollow laughing and horseplay of boys trying to distract themselves from the long-dreaded day that had hung over the latter part of the summer like a toxic mist. It had finally come: the first day back at school.

“What time is it at all? My watch has stopped,” called Laverty.

“Ten to nine,” announced a bronchitic voice from the silence.

“Jaysus, but they’re eager, the little bastards,” replied Laverty, taking a deep, despairing drag of his cigarette.

“Eager, my arse,” huffed Mr. Devlin, the Biology teacher, from the doorway. “They’re just early cos they don’t remember how to be late from last year.” Mr. Devlin popped two more mints into his mouth and breathed on his hand to see if the dead beer smell was still there. He had only intended to have a couple of pints and get to bed early but then the night had spun a little out of control.

“Good morning, gentlemen! Nice of you to turn up on time for once, Mr. Devlin. We hope this is a new leaf,” clipped Mr. Pollock’s angular vice principal’s voice. He was right on Devlin’s heels. “Here are the class lists. To the hall with you now!” He dropped the sheaf of typed pages on the table, whisked around on the ball of his right foot with a mousey squeak of his brothel-creepers, and was gone.

“Poxy creep!” muttered Spud Murphy under his breath.

Mr. Barry, the Chemistry teacher, picked up the lists and started dealing them round the staff room like a stacked tarot deck that contained nothing but death cards.

In the monastery common room, Brother Kennedy pursed his thin cracked lips and ran his hand over his balding skull, smoothing the wisps of white hair over the bright red parchment of his scalp. He looked up briefly as the door creaked open and Brother Boland jittered his frail frame into the room. Boland’s watery blue eyes cowered in their sunken sockets and darted about the room as if expecting some sudden attack. The man had jittered for as long as Brother Kennedy could remember. Brother Kennedy was in his seventies and Boland seemed to him to be at least a generation older. School lore had it that when Brother Boland was in his thirties, one of the sixth years had dropped a desk on him from a third-floor window while allegedly trying to knock dirt out of the inkwell. The boy had been dispatched to Saint Loman’s Reformatory and later escaped to London. Brother Boland was never quite the same after it.

Brother Kennedy rarely exchanged words with Boland. It was too slow and arduous an undertaking, particularly first thing in the morning when the man’s speech was still staggered and hesitant.

“Ge-ge-ge-ge-ge-good morni-ni-ni-ni-ni-ni …”

“Good morning, Brother Boland.” Brother Kennedy snapped his newspaper and went back to the Gaelic football results. His county, Mayo, were not doing too well but he still held out hope that they would make the Connaught finals. More hope than he could ever hold out for the pathetic school team. The scholarship boys, mostly from the local flats and tenements, had the audacity to show their ingratitude to the Brothers by being good at soccer only. It was typical of bloody Dubliners. The more malleable boys who came from the suburbs because their parents were under some illusion about the reputation of the school were just not rough enough for Gaelic football, try though they might.

New Roof for Mullingar Dog Track in Jeopardy, Bishop May Intervene, Brother Kennedy read with interest.

Brother Boland checked his watch against the wall clock and left the common room with a reptilian urgency.

Francis Scully turned into Greater Little Werburgh Street, North. There, on the corner with the West Circular Road, stood The Brothers of Godly Coercion School for Young Boys of Meagre Means, or “De Brudders,” as it was more commonly known.

The sun was shining somewhere, but not anywhere near where Scully was. A dark shroud of despair surrounded him. The long summer of drizzly days with scattered outbreaks of sunshine lay lost behind him; it was now time to go back to school.

He looked up from the ground and the appalling sight of the dead end of Greater Little Werburgh Street, North, and the heavy school gates greeted him like a bout of stomach cramps.

Forty shades of grey was the only way to describe the schoolyard. The school buildings and the monastery that surrounded it on three sides were grey. Even the windows seemed to be grey. The concrete surface of the yard was grey. The sky above it was grey. The boys’ shirts, sweaters, and trousers were grey. The only thing that broke the uniformity was the occasional black school blazer. The yard was a variegated fugue on the theme of grey. Had it been music, it would have been slow, mournful stuff played on a bassoon, a tuba, and the pedals of a church organ.

Scully turned heavily into the yard and looked around. It was exactly the same as last year, but even familiarity with the scene could not lessen its soul-sapping effect. The dull murmur of subdued teenage voices only added to the overall gloom.

“Scully, ye bollix! Are they lettin’ ye back in?”

Scully looked over to see Lynch and McDonagh sitting beside the bin in the small covered shed. He walked over and stood in front of them.

“So?” asked McDonagh.

“So, nothing,” muttered Scully.

“Yeah, right,” agreed McDonagh.

“Shite,” added Lynch meaningfully. He extended his cupped hand and Scully took the lit cigarette it contained. He took a long drag and exhaled slowly so as not to cause a cloud.

“Now, you boys!” It was Brother Loughlin, the Head Brother. He was on the steps of the monastery. “You will all go to the hall and get your class assignments there. First years will report to Mr. Laverty, second years to Mr. Devlin, third years to Mr. Skelly, fifth years to Mr. Murphy, and sixth years to Mr. Barry.” Such menial tasks as calling out names were beneath the Brothers and left to the junior lay teachers.

No one moved.

“To the hall!” shouted Brother Loughlin. He started down the steps in a wave of cruel blubber, smoothed his eyebrows—apart from his nasal hair the only visible hair on his whole person —and took his leather strap out of the special pocket of his cassock.

Slowly the grey, reluctant sludge of boys began to ooze out of the yard and across the big yard to the hall. Scully, Lynch, and McDonagh fell in with the flow when they saw Brother Loughlin swing his leather and start in on some third years who were leaning against the wall in a manner unbecoming of boys who should be on their way to the hall.

“Jaysus! Bollocks Pollock for form master. What is that for?”

“He’s a complete bastard.”

“It’s cos of the fire in the basement.”

“Can’t prove anything.”

“No. But …”

Scully, Lynch, and McDonagh thus examined their fate as they walked back from the hall. It had been good fun for a bit, pretending not to be able to hear their names called out, answering for other people, calling out that others weren’t coming back this year because they had been taken away by zombie spaceships, but there was no escaping it: they were going to have Pollock as their form master for the rest of the year, which at that moment felt pretty much like the rest of their lives.

“Yeah, and what is Smalley Mullen doing in our class?”

“Don’t know. Maybe we’re the new A class.”

The three of them burst out laughing.

“In ainm an Athair agus an Mhic agus an Spiorad Naomh, Amen.” Mr. Ignatius Pollock, the first lay vice principal in the history of the school, finished blessing himself in the tongue of the Gaels, and the prayer, probably a Hail Mary from what the boys could gather, was done. Mr. Pollock reflexively and pointlessly smoothed his wispy ginger hair over his bald spot, pursed his thin lips, and proceeded to call the roll.

“… McDonagh?”

“Here. I mean, anseo.”

“Mullen?”

“Here, ehm, present, ehm, anseo.”

“O’Connor?”

“Anseo.”

“Rutledge?”

“Here, eh, anseo.”

“Scully?”

“Anseo.”

“Sullivan?”

Who was Sullivan? The only Sullivan anyone knew was Kieran Sullivan and he was in sixth year. There had been no Sullivan in third year with them last year. Mr. Pollock looked up from the roll book.

“Finbar Sullivan? Fionnbarr Ó Súilleabháin?”

Still no answer.

“We go to the trouble of making last-minute arrangements to fit him in and he does not even deign to turn up on the first day,” Pollock complained to no one in particular. From the top pocket of his time-shined suit jacket, he removed a red pen and tut-tutted to himself in disapproval as he marked Finbar Sullivan absent.

He carefully examined the boys before him. Suddenly he spun around and furiously wrote the days of the week across the blackboard: Dé Lúain, Dé Máirt, Dé Céadaoin, Déardaoin, Dé hAoine. Down the side he wrote the times in fifty-minute intervals from nine through half past three.

He turned around and looked inquiringly at the boys, his eyebrows raised.

McDonagh raised his hand. “Sir! Sir! Sir! Sir! Sir! Sir! Sir! Sir!” he implored breathlessly, as if there were stiff competition to volunteer an answer.

“An tUasal, Mhic Donnacha!” announced Mr. Pollock, and gestured to the boy.

“Irish words, sir,” answered McDonagh with a false enthusiasm you could have bottled. That was McDonagh’s thing. It was a subtle and relatively safe form of disruptiveness, that and being able to faint at will. He was a reasonably good farter too but not one of the best, not up there with Lynch who could play simple tunes out of his arse.

“Ní thuigim,” announced Mr. Pollock.

McDonagh looked crestfallen. He stood up slowly, walked sadly to the door, opened it, went outside, and softly closed it behind him. Mr. Pollock stood rooted to the spot. He was momentarily at a loss. He roused himself, went to the door, and opened it. McDonagh turned and looked at him, his face a caricature of contrition. Mr. Pollock motioned him back inside the class and stared at McDonagh questioningly.

“You told me to get out, sir.”

“No, sor. I told you that I didn’t understand. Ní thuigim. I don’t understand. Understand?”

This was one of Mr. Pollock’s favourite ways of slighting the boys. “Sor” in Gaelic meant louse and it was the custom during colonisation for the tenants to take what little pleasure they could get by addressing their rack-renting landlords with the word.

McDonagh saw a great opportunity for further confusing the issue by asking if “Ní thuigim” meant “I understand” or “I don’t understand,” but something glinted dangerously in Mr. Pollock’s eyes and he thought the better of it. Just as he was about to answer, Mr. Pollock suddenly turned sideways and his leather was out and he was smacking McDonagh hard across the right hand.

“Ní thuigim. I don’t understand. Ní thuigim. Repeat!” he shouted at McDonagh, each syllable punctuated with the sharp sound of the leather on the boy’s palm.

“Ní thuigim, I don’t understand,” said McDonagh tonelessly.

“Suigh síos,” barked Mr. Pollock, and then watched McDonagh as if defying him to deliberately misunderstand that one. McDonagh walked sullenly back to his desk and sat down as instructed.

The heavy post-leathering silence settled down on the boys like dense soot. The lines were drawn. No messing around. It was true what they’d heard. Pollock was a complete bastard. He was as bad as any of the Brothers. This was the shape of the year to come.

Grimly they copied down the timetable Mr. Pollock wrote on the blackboard, dismayed to see that Mondays, Tuesdays, and Wednesdays were going to start with double Irish with him and last thing Friday was Religion with him.

Mr. Pollock walked around the class checking that they were copying correctly. “You would want to take more care of your handwriting, Mr. McDonagh,” he said pointedly as he passed the boy’s desk. McDonagh said nothing and went on writing with his swollen, throbbing hand.

“Now, we will walk silently down the stairs and proceed to the hall for the mass,” announced Mr. Pollock when he had completed his circuit of the class.

3

Father Flynn cleared his throat nervously. This was his first school mass as chaplain to the Brothers of Godly Coercion. As the newest priest at Saint Werburgh’s parish, this extra duty had fallen to him. He had trimmed his beard three times the previous night. The uneven growth he now presented to the world was what he determined to be his most youth-friendly, approachable, and understanding face.

He smiled broadly at the hallful of boys in front of him and let rip: “We are all God’s family. And He has asked us to go on a journey with Him. As we begin this new school year, we are like pioneers in the cowboy films that I am sure you boys like so much. You know the ones with the covered wagons going across the desert in search of their promised land. Well, Jesus is like our scout. He rides ahead of us and checks the way and then comes back to warn us of any dangers that might lie ahead.”

“Deadly! Jesus and the Holy Ghost trying to sell crucifixes and holy medals to the Apaches,” whispered Scully.

Lynch started to chuckle. That was always dangerous and Scully knew it. Lynch had one of those soft, shaking, crazed chuckles that was really contagious. With anyone else Scully could pass off his remarks and keep a totally straight face himself, but if Lynch started to giggle …

“Many times when Jesus returns from His scouting missions we are too busy or proud to listen to Him. Many things can get in the way. Sometimes we are distracted by our children crying or we are worried about finding food or water, or sometimes we are working out how long we will have to save up for those new football boots. Sometimes we don’t listen to Our Lord and insist on walking into danger …”

“And then the Apaches cut yer balls off and wear them round their necks on a string.” Scully couldn’t help it. It just came out.

Lynch started to shake in the plastic chair beside him. Scully was starting to go too. He was chugging with silent hysterics and starting to sweat.

“We must try to listen to Our Lord when He warns us of the dangers. We must open our hearts to Him …” continued Father Flynn.

“Shut up, ye wanker, or I’ll open yer head for ye,” muttered Lynch. It wasn’t funny, but it was enough. They were both now giggling helplessly. Lynch tried to cough his laugh away. That made Scully worse. He tried really hard not to listen to any more of Father Flynn’s sermon. Another crack and they would be laughing out loud and then there would be trouble.

Scully put his fingers in his ears and started to hum softly: anything not to hear Father Flynn say something stupid like “The Lord is there to save our scalps,” anything but that. He felt Lynch’s rocking beside him subside and decided it was safe. He took his fingers out of his ears. The sermon was over. They were on the home straight. Soon it would be lunchtime.

Mr. Pollock then struck up on the warped, untunable school piano. He launched into “The Lord Is My Shepherd” with far more gusto than ability, hitting bum notes with artful and oblivious incompetence. Lynch started to sing along, following Mr. Pollock’s bum notes. That did it. Scully was in hysterics. His shoulders shook violently as he tried to stifle the laugh.

Suddenly, out of nowhere, the bulk of Brother Loughlin burst through the sea of plastic chairs. Scully saw him coming but there was nothing he could do; he was caught. Lynch put on his most angelic face and continued to sing tunelessly along with Mr. Pollock’s playing. Brother Loughlin grabbed Scully by the strands of hair above the ear and dragged him out of the hall.

“So, Mr. Scully? Something funny about ‘The Lord Is My Shepherd’ then, is there?”

“No, Brother,” mumbled Scully as the words The Lord Is My Apache Wearing Loughlin’s Balls Round His Neck flashed momentarily across his mind.

Somehow his face betrayed a hint of inner smirk. In a surprising blur of speed for someone so bulky, Brother Loughlin whipped his leather out of his sleeve and smacked Scully across the face with it.

The boy’s face smarted and tingled. He had been caught completely off guard. His eyes watered but he stared at Loughlin as steadily as he could. He would not give the bastard any satisfaction.

“So, Mr. Scully? Anything else to say for yourself? Any smart-alecky remark you would like to make?”

“No.”

“No, BROTHER!” shouted Brother Loughlin. He grabbed Scully’s right hand and began to leather him, punctuating each word with a blow. “I’ll! Teach! You! Manners! You! Little! Thug! Now get back to your seat and no more messing out of you!”

Brother Loughlin pushed Scully through the doors into the hall.

“Go in peace now to love and serve the Lord,” intoned Father Flynn from the altar on the stage as he blessed them all. Mr. Pollock struck up the last hymn, “Nearer My God to Thee.” It was one of his favourites. That only increased the mauling he subjected it to.

Scully walked slowly back to his seat and stood beside Lynch, who looked sideways at him with the minimum of head movement.

“Fucking bastard! Fucking fat bastard!” hissed Scully under his breath.

Lynch nodded and went back to annihilating the hymn with tuneless gusto: “Neeeeerer my Goooooodddd toooooo Theeeeeeeee, neeeeeeeeyrer tooooooooooo Theeeeeeeeeeee. Eeeeeeeeen tho it beeeeeee a crosssssssssss …”

Scully smiled wanly and rubbed his hands together to deaden the stinging. “Fat fuck, he’s dead,” he continued to mutter under the strains of half-hearted hymn-singing around him.

There were still two verses to go when the lunch bell rang out from the yard. Mr. Pollock’s playing seemed to slow down. Lynch gave up his derisory singing and started to shift agitatedly from foot to foot. It was one thing to waste what would have been a double math class with this mass, but it was very much another to start messing with the lunch break. Lynch felt very strongly about this.

With a final chord that could only be described as G-demented, Mr. Pollock put “Nearer My God to Thee” to uneasy rest and the mass was finally over.

“All boys will assemble outside with their form master and return to their classes and gather up their things. Today being Friday, we will be granting you a half day. Monday will follow the timetables you have been given,” announced Brother Loughlin from the stage.

There was no cheering or whooping to celebrate the half day. All energy was expended in getting outside as quickly as possible. As Mr. Pollock and his class were close to the back, they got themselves organised and reached the school first. The first boys stopped suddenly and stood at the edge of the yard.

“What’s wrong with you boys there? Move on!” snapped Mr. Pollock from the back of the group. He stepped forward and then he too stopped in his tracks.

The grey concrete of the yard was littered with another, different grey. Strewn around were shattered roof slates that lay there like birds that had suddenly turned to stone and plummeted from the sky. There was not a breath of wind. As they watched, another slate slid from the roof and sailed to the ground where it smashed into pieces with a weird metallic crash.

Mr. Pollock looked cautiously up at the roof of the school. He could see nothing.

“Right, you boys, stay close to the wall. Get your things from the class and go straight home. Straight home! No loitering about the yard!”

They ran for the door and up the stairs.

“Deadly! The place is falling to bits!” shouted McDonagh.

“Wonder who done them slates. I’d never’ve thinkin’ of that,” remarked Lynch admiringly.

As they left they saw Mr. Pollock supervising proceedings, letting one class at a time go up and get their things. His voice was a brittle whine as he shouted instructions and lashed out with his leather at the inattentive and the overeager.

* * *

Conall McConnell, School Janitor, Grade IV, sat quietly in his shed behind the school hall waiting for the kettle to boil. As first days went, this had not been a bad one. There had been no mess-ups in classes or desks, and while they were all at mass he had been able to patch the puncture on the back wheel of his bicycle.

McConnell pulled his milk crate over to the door and sat watching the sparrows pick at the moss on the twenty-foot wall that separated the school from the adjoining Lombard Street Jezebel Laundry. It was still not too cold and he could sit beside the open door and enjoy his tea. From the yard he could hear the muted sounds of the boys drifting home. A nice cup of tea and then he could head home by way of Stern’s, the butchers, and get a few nice bits of lamb’s liver for the tea. Mrs. McConnell was very partial to the bit of liver.

From the pocket of his overalls he removed a small notebook and a stubby pencil that he had taken from Hackett’s, the bookmakers at Binn’s Bridge. He stared at the sliver of sky above the wall that divided the school from the laundry and wrote:

In the autumn of desire

Screeds of cloud flow tear

Across the mind’s eye

Billowing, billowing

Filled with the rain

Of promise.

How many autumn breezes

Have promised to keep

Close to—

“Mr. McConnell, I want you to look at the roof!”

Brother Loughlin was standing over him looking down at the notebook with profound distaste. It was all very well for a member of the working class to know how to write, but one who did it for recreation was deeply suspect in Brother Loughlin’s estimation.

“And what might be the matter with the roof, Brother?”

“There are some slates that have fallen off on the school side. The yard is littered with them. You might want to take a look at it now that we have given the boys a half day. Best get it fixed before they all come back on Monday.”

“But I’m not a roofer. I’m a janitor.”

“I am well aware of that, Mr. McConnell, but where do you expect me to find a roofer at this hour on a Friday afternoon?”

“It’s all the same to me.”

“Are you saying you won’t fix the roof?”

“Ah, no. That wouldn’t be exactly what I am saying. What I am saying is that it would probably be better to get a certified, accredited roofer to look at it. I could see if there’s any of the lads I know would take a look at it for you.”

“Mr. McConnell! I don’t have time for this hairsplitting! Either get up on that roof or find yourself another position!”

“But Brother, I could be sanctioned for crossing over demarcation lines. Brannigan Brothers could blackball me. You know they run the whole shebang. I’d love to fix the roof for you but I’m a janitor. I can’t be doing that. Imagine if there were roofers wandering in here off the streets to mop out the toilets or lock the gates or—”

“The roof, Mr. McConnell!”

“All right. All right. I’ll take a look at it.”

“Good, and don’t be too long about it.”

Before McConnell could say anything else his kettle started hissing and spitting, threatening to extinguish his kerosene stove.

“I didn’t know you had a stove in here, Mr. McConnell,” said Brother Loughlin archly, every syllable implying that there probably shouldn’t be one in the janitor’s shed.

“I said I’ll go and look at it now.”

“Well be quick about it then!” replied Brother Loughlin and strode away.

“Ah, go ask me arse, ye big fat fucker!” muttered McConnell, then turned off the stove.

“Ah, for fuck sake!” exclaimed McConnell when he finally made it on to the roof. While sitting in his shed bloody-mindedly finishing his tea, he had convinced himself that the roof would be a minor matter of a few loose slates. A couple of nails and a couple of bits of plywood to patch the holes and he would be off home.

Now, as he stood unsteadily on the steeply pitched roof, he saw that the slates had not all slid from the same part of the roof. With almost mathematical precision the slates had fallen from roughly fifty different spots and the area of damage spread over the whole west side of the roof.

“I’ll be here all fucking day!” McConnell moaned aloud and turned to make his way back down to collect the necessary tools. As he moved he noticed the roof joist in one of the nearby holes was almost completely rotted through. “No way I’m fixing that as well.” He made his way carefully back to the gable end and climbed down.

4

Whatever tiny bit of excitement Finbar might have had about going to a new school had been severely damaged by Saturday’s encounter at the corner shop. He had spent all day Sunday just moping around the house, refusing to go out after mass while his father tried to unpack and brighten the tiny cement backyard with fuchsias and geraniums he had brought from their garden in Cork.

Redneck, Culchie, Bogman, Muck Savage, they had shouted at him in bad Cork accents and then followed him down the street imitating his walk.

“Finbar! Come on! I won’t tell you again. You don’t want to be late,” yelled Mrs. Sullivan from the bottom of the stairs.

From the other bed Declan glowered groggily at him: “Get up before I split you, you little prick!” Declan was unemployed and seemingly unemployable. The army had already turned him down in eight different counties.

“Ah, go feck off. Get up yourself and get a job, ye lazy shite,” muttered Finbar. This was awful. On top of everything else he had to share a room with Declan now. In Cork he’d had his own room. Dublin was just bloody perfect.

“Finnnnbarr!” called his mother again.

“I’m up! I’m up!” he snapped.