Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

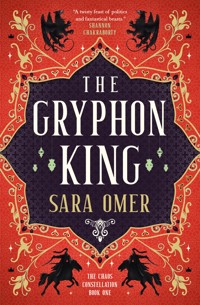

The first in a sweeping Southwest Asian-inspired epic fantasy trilogy brimming with morally ambiguous characters, terrifying ghouls and deadly monsters. Combining cut-throat dynastic politics with expansive worldbuilding and slow-burning romance, this stunning debut is perfect for fans of Godkiller and Samantha Shannon. "A twisty feast of politics and fantastical beasts." Shannon Chakraborty Bataar was only a child when he killed a gryphon, making him a legend across the red steppe. Now he is the formidable Bataar Rhah, ruling over the continent that once scorned his people. After a string of improbable victories, he turns his sights on the wealthy, powerful kingdom of Dumakra and their vicious pegasus-mounted warriors. Nohra Zultama has no fear of the infamous warlord who marches on her country. She and her sisters are Harpy Knights, goddess-blessed and lethal. But as deceit and betrayal swirl through her father's court, she soon learns the price of complacency. With Dumakra under Bataar's rule, Nohra vows to take revenge—yet her growing closeness to the rhah's wife, Qaira, threatens to undo her resolve. When rioting breaks out and strange beasts incite panic, Nohra must fight alongside Bataar to keep order, her mixed feelings toward the man she's sworn to kill becoming ever more complicated. Old evils are rising. Only together will Nohra and Bataar stand a chance against the djinn, ghouls, and monsters that threaten to overrun their world.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 626

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

Map

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Praise for

The Gryphon King

“A twisty feast of politics and fantastical beasts—I cannot wait to read more of Omer’s work.”

Shannon Chakraborty, New York Times bestselling author of The Adventures of Amina al-Sirafi

“Omer has created an engulfing fantasy world, as vicious as it is human, not shying away from the brutality of conquest or the deeply complex characters who fight for it. The monsters are horrific. The slow-burn yearning is borderline inhumane. I stan an angry woman reaping vengeance with a scythe from the back of a nightmare fanged pegasus.”

S. A. MacLean, Sunday Times bestselling author of The Phoenix Keeper

“A sweeping, magnificent epic of elaborate worldbuilding and intricate court politics. Omer skillfully explores the complexities of conquest and the flawed characters at its helm. One of the best fantasies I’ve read in years!”

Hadeer Elsbai, author of The Daughters of Izdihar

“Starts with a bang and never lets off the gas. Deeply flawed yet lovable characters populate a world filled with twisty politics and fearsome beasts in equal measure. In this absolute firecracker of a debut, Omer balances unflinchingly grimdark elements with a deeply human softness rarely seen in this side of fantasy. Fans of A Song of Ice and Fire and The Poppy War should run, not walk, to the bookstores for this one.”

M. J. Kuhn, author of Among Thieves

“Dripping with blood and glitteringly deadly court politics, The Gryphon King dazzles with characters as likely to bite the hand that feeds them as a man-eating pegasus… both sweeping and wonderfully intimate.”

Gabriella Buba, author of The Stormbringer Saga

“Intricate in its political intrigue, delightful in its conflict and tension, brilliant in the complexity of characters, and a wonderfully mythic story of love and sacrifice.”

Ai Jiang, author of A Palace Near the Wind

“Alive with politicking families, fantastic beasts, and a deftly crafted storyline… a delicious cocktail of wonder and story sure to please every fantasy lover. Omer is a roaring new talent with boundless imagination, whose characters will stay with you long beyond the pages of this book! You want this book and you want it now.”

Tobi Ogundiran, British Fantasy Award-winning author of the Guardian of the Gods duology

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.com,

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Barnes & Noble,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

The Gryphon King

Print edition ISBN: 9781835412831

E-book edition ISBN: 9781835412855

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: July 2025

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© Sara Omer 2025

Sara Omer asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

Map artwork by Allen Omer.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

EU RP (for authorities only)

eucomply OÜ, Pärnu mnt. 139b-14, 11317 Tallinn, Estonia

[email protected], +3375690241

Typeset in Palatino LT Std.

For everyone who wishes they could pet the man-eatingmonsters in their favorite fantasy books.

Characters

DUMAKRA

HARPY KNIGHTS

NOHRA ZULTAMA,

princess, wielder of the sickle-staff Bleeding EdgeSAFIYA ZULTAMA (Saf),

princess, Nohra’s half-sister, wielder of the sword Queen of BeastsCALIDAH (Cali),

Clemiria’s daughter, Nohra’s cousin, wielder of the crossbow CovenantAALYA ZULTAMA,

princess, Nohra’s half-sister, wielder of the shield SegreantMERCY,

Nohra’s pegasusPRUDENCE,

Safiya’s pegasusROYAL FAMILY

RAMZI ZULTAMA,

zultam, ruler of DumakraHIMMA,

queen motherTHORA,

Aglean-born Dumakran queen, Nohra’s motherRAMI ZULTAMA,

crown prince, Nohra’s brotherMERV ATTAR,

Ramzi Zultama’s first wife, Dumakran queen, mother of Aalya and NassarNASSAR ZULTAMA,

prince, Nohra’s half-brotherCLEMIRIA ZULTAMA,

Nohra’s aunt, queen of Rayenna, former Harpy Knight, former wielder of Queen of BeastsFARRAH ZULTAMA,

Nohra’s aunt, former Harpy Knight, former wielder of Bleeding EdgeHANA ZULTAMA,

princess, Nohra’s half-sister, Syreen’s twinSYREEN ZULTAMA,

princess, Nohra’s half-sister, Hana’s twinZIRA,

concubine from the islands north of MoshituSURI,

former concubine from Moshitu, Safiya’s motherMURAAD ZULTAMA,

cousin of RamziABAYAE,

Nassar’s monkeyQUEEN PURRI,

Aalya’s catSERVANTS

DARYA DAHEER,

Nohra’s talmaid, a cookFAHAAD,

stablemaster, Zultam Ramzi’s servant-ward from MoshituLAILA,

Safiya’s talmaidADEEM ADEN,

court physician, medicine mavenRAMMAN MYTRI,

head servantCAPTAIN MADY,

captain of the palace guardORIK,

former stablemasterKAATIMA,

kitchen maidOTHERS

ERVAN LOFRI,

Minister of Commerce, Merv Attar’s cousinJAWAAD LOFRI,

Ervan Lofri’s sonKASIRA LOFRI,

Prince Nassar’s betrothed, Ervan Lofri’s daughterYARDAAN NAJI,

grand vizierMAHVEEN NAJI,

Yardaan Naji’s daughterMAJEED JABOUR,

Minister of FaithFAKIER,

a generalVIZIER SARTARID,

formerly controlled the town of MinevaWAEL BAHDI,

captain of the Kalafar city guardZAREB,

one of the guards at the Forked TowerDIACO SHAAM,

son of the Minister of AgricultureTAMYR ALI,

emissary in the village of HalamutHISTORICAL FIGURES

NUMA ZULTAMA,

former zultamOMAAR THE

PEACEMAKER,

former zultamROKSANYA ZULTAMA,

Nohra’s great-great-grandmother, former queenSHASSAM NAJI,

former Master of ArchitonicsOBEYD,

strategistRED STEPPE

BATAAR RHAH,

rules all the Utasoo tribesQAIRA,

Bataar’s wife, Shaza’s older sisterTARKEN,

a general, Bataar’s bloodsworn brotherSHAZA,

a general, Qaira’s younger sisterERDENE,

Bataar’s eagleBOROO,

Bataar’s healer/shamanOKTAI,

Bataar’s footman, Tarken’s cousinMARAN,

Qaira’s handmaidCHUGAI,

Tarken’s little brotherGANNI,

Bataar and Qaira’s daughterBATO,

Bataar and Qaira’s sonTOBUKAAH RHAH,

fought against Bataar in the war for the Red SteppeMUKHALII RHAH,

fought against Bataar in the war for the red steppe, kidnapped women and childrenCHOYANREN

RUO SACHA,

empress in Tashir, leader of ChoyanrenYEEON,

councilwoman in TashirAGLEA

MERIC WARD BARRISTER,

lord of BridgewallAUTUMN, 355

Over a decade after the Sunless Months, food remained scarce, especially among the nomadic tribes west of Dumakra.

—A Dark Era

The eagle screeched as she wheeled through the sky high above camp, her tethers waving like the hair on a war banner. Whoever had cut her leash was probably watching and laughing. Bataar weighed a piece of uncooked meat in his hand, disgusted at himself when his stomach growled. Coaxing her down using the chunk of liver felt wasteful, but it couldn’t be helped.

“Going hunting? There’s good game at the foot of the mountain,” an old man called out, gesturing toward the snow-capped red peaks in the distance. With a broad smile, he warned, “Watch out for the gryphons, though.”

Bataar stiffened. The man’s drinking companions broke into riotous laughter.

“Hah, his face! Like you shoved an arrow up his ass.”

Fermented milk sloshed from a cup, splashing Bataar’s boots. He stepped back, grimacing. He was only fourteen, but he’d been hunting since he could ride a horse. His pride was already mangled and dirty—it could take a hit, and so could he. These men were shadows of the hunters and fighters they’d been before wars and vermilrot outbreaks had left them scarred and gaunt. The rot took better men—it had killed Bataar’s father two summers before. Still, he wasn’t going to start a brawl with a gaggle of drunks over some teasing. He already lost more fights than he won.

These wrinkled sots had never seen a gryphon, and neither would Bataar. Each year, the gryphons moved closer, but never near the mountains. Attacks on the steppe were so rare that the stories had begun to sound like fables to fill children’s heads when their bellies were empty.

Soon, winter would freeze the river. The herds would shrink, forcing everyone to ration, just like last year, and the years before. Hunger was the real monster, and Bataar knew how deep its fangs pierced.

He tossed the meat, and Erdene dove down. When she’d scarfed back the chunk of liver, he snatched up her leather jesses where they trailed in the dirt.

“You better still be hungry,” he whispered. He needed her ravenous.

Turning away from the mocking laughter, Bataar slung his bow over his shoulder and set off across camp to gather his friends. Tarken crouched near one of the cookfires, binding fletching to the shafts of arrows with cord.

Bataar nudged him. “You ready?”

Shaggy hair fell in Tarken’s face as he squinted up. “Why do you look like your eagle crapped in your porridge?”

Bataar’s ears burned. “Just get your brother.”

Tarken held his hands up. “Alright, alright.”

As his friend disappeared beyond the threshold of his tent, someone snickered. “Getting a little hunting party together? It’ll be gerbil stew for dinner, then.” Bandages covered the boy’s head, hiding where an eagle had almost gouged out his eye.

His lackeys cackled. They were still milking the scratches from their hunting accident. Lately, these losers had done nothing but hang around camp, picking on the girls, stuffing their faces, and sneering at anyone they thought was below them, which was almost everyone, especially Bataar.

Respect was earned on the red steppe, and Bataar seemed wholly unremarkable, with his black hair, plain face, and no accomplishments to boast of. He wasn’t the cleverest or tallest or most vicious, but these useless idiots were wrong to underestimate him.

The boy’s good eye narrowed. “What are you looking at, whelp?”

“I was just thinking it’s unfair for someone to be both horse-faced and stupid,” Bataar said, then bolted before the other boy’s thick tongue could form a response.

Tarken burst out of his tent, running to keep up. “What’d you do?”

His little brother Chugai clung to his side, too big to carry like that anymore, his eyes screwed shut and small hands clenched into fists around Tarken’s tunic.

“What makes you think I started it?” A rock flew past Bataar’s cheek. A second struck him in the back, and he almost fell. On his arm, Erdene screeched and thrashed her wings, buffeting his face.

“Cut it out, bird meat!” a girl shouted, emerging from her home across the circle of round tents and throwing a stone back at the older boys. A pained groan answered her hit. Shaza was tall and strong for a girl. Smirking and satisfied, she turned on Bataar and Tarken. “If you dog-brained idiots are going to start a fight, at least finish it. I can’t always save you.”

“Like we needed you!” Tarken snapped.

Bataar winced. “We were coming to tell you I found a good hunting spot.”

She looked at them doubtfully. “I’ll believe that when I see it.”

“You coming or not?” Tarken balanced his brother in one arm, rubbing a spot on the back of his own head where he must have been hit by a rock.

Shaza shrugged, impassive as ever. “Tell you what: let me bring my sister and I’ll come.”

Bataar scowled, picturing her older sister Qaira’s annoying big ears and stupid blushing face. Finally, because he couldn’t think of a good enough excuse, he said, “Fine, bring her.”

* * *

Bataar flung up his arm, casting his eagle into the air. Erdene flew swifter than a storm, shooting across the field. The hare leapt above the tall grass, narrowly evading her talons. Bataar whistled for Erdene to circle back. She arced around, diving to sink sickle claws into its neck and dragging its thrashing body hard across the red dirt.

This side of the river, eagles were the most dangerous predators, alongside the falconers who hunted with them. The hare’s kicking legs went limp. Something iridescent spilled out of its slack face, disappearing like smoke on the wind.

Not everyone could see spirits.

Bataar had been born with his umbilical cord constricting his neck, his skin tinged blue. As soon as his soul had come into this world, it had almost left it. If anyone knew he could see souls, they’d make him become a shaman, reading rune stones and interpreting smoke signs for the great rhahs. But the spirits didn’t whisper wisdom to him. Instead, every death he witnessed was a reminder that he’d robbed Preeminence of a life it was owed. The universe hunted him, and Bataar knew never to look a beast in the eyes unless you were ready for a fight.

He had a plan. He’d keep his sight a secret and get stronger. When he was tougher than everyone in their camp, he would challenge a steppe king, be named a rhah, and rule not only their tribe, but all the Utasoo. And after that, he’d become a king of the world. Then he would finally be worthy of what he’d stolen.

He tried not to grin like an idiot as he imagined riding into battle one day with Erdene on his arm. He’d have a long mustache, a sable cape, and hundreds of thousands of men sworn to his cause.

For now, he just shooed Erdene off the hare before she could rip open its belly, tempting her with a piece of organ meat from his bag. He tied the dangling creature to his saddle and climbed back on his horse. Erdene choked down the heart meat and squawked, gliding up to perch on Bataar’s forearm. Her bloodied talons dug like needles into his vambrace.

“What do I have to do before the men let me hunt with them?” Shaza asked. Her black rope of a braid swished as her mare came abreast of them.

“Are we not good enough for you?” Tarken said around a mouthful of orange berries. He and his little brother shared a horse ahead of Bataar, its legs deep in the ruby-tinted grass.

Shaza let her icy silence be an answer.

“That’s insulting,” Tarken grumbled.

Tarken’s little brother bounced in the saddle, holding a child-sized bow. Chugai was only six, but Bataar had been even younger when he first rode with his father, watching the eagles take down wolves in the snow.

Shaza’s rabbity sister Qaira brought up the rear, wearing ribbons in her braided hair. She caught Bataar looking back and glanced away, flushing. He bristled. Everyone admitted Bataar was a passable shot, better than most of the boys, but he wasn’t as good as Qaira. Still, Shaza’s sister was older than him, yet she bawled when sheep were slaughtered. Bataar didn’t even flinch as he watched souls rip free from bodies, shimmering in the air and evaporating into the sky.

A timid rabbit like her couldn’t even see what was really worth being scared of.

As the noon sun began to dip, they dismounted by a stream to let the horses drink. Surveying their kills, Shaza scoffed. “They’ll laugh us out of camp.”

“Food is nothing to laugh at,” Bataar told her. Blood matted the raked-through pelts of the hares. Erdene ruffled her feathers as she preened, surveying her mangled quarries proudly.

Tarken glanced over his shoulder. “Hey, where’s Qaira?”

Shaza fixed him with a look. “She’s picking berries. We passed the bushes ages ago. How’d you two not even realize she left?”

“She’s so quiet, how could we?” Bataar muttered. “Why’d she bother bringing a bow anyway if she’s going to close her eyes whenever there’s something to kill?”

“She just doesn’t have the stomach for it.”

“Well, at least she’s not useless,” Bataar admitted, starting to smile. “Someone’s gotta mend our clothes and cook for us.”

Tarken laughed. Chugai laughed because his big brother was laughing.

Shaza rolled her eyes. “You two are idiots. You’ll ruin the kid.”

The four drifted apart, refilling water skins and cleaning their knives. Bataar sheathed his, watching Tarken and his little brother kick stones along the river’s burbling edge.

Winter was a biting song on the wind. High above, a perfect blue stretched over the horizon. People said the Preeminent Spirit looked like the calm sky, but that wasn’t true. Bataar could see Preeminence’s face leering down at him from above, and They were terrifying.

Ahead, the snow-capped Red Mother stretched into the sky. Except for the wind and his hunting party’s voices, the hills were quiet. A sulfurous smell hung in the air, fouler than any fire. Gooseflesh prickled on Bataar’s neck. Instinctively, he drew his short bow off his shoulder.

“Look at that shiny one, Chugai.” Tarken’s voice became smaller the farther he walked, blabbering about rocks.

Erdene cried in Bataar’s ear, insistent, digging her talons deep. A twig snapped, and the horses whinnied, shuffling nervously. Bataar turned, expecting to spot the black eyes of an antelope.

Instead, his gaze fell on a gryphon.

Golden irises locked with his, and Bataar stood paralyzed. A clear membrane slid over the gryphon’s eyes. It looked like a huge lion, except for its beak and feathered back legs ending in taloned feet. Its tufted tail lashed the air.

Bataar’s chest tightened, his body trembling and heart pounding. The gryphon rose from its crouch. Standing as tall as Bataar’s sternum, it spread its wings. They could all have made a line, arms outstretched, and they wouldn’t have reached as far as the tips of its longest feathers. It was darker than sable, than tar, like a hole torn in the night sky. Its footfalls were soft as it slunk forward, hardly disturbing the grass with its bulk.

Beside him, Shaza gasped. The gryphon was lean and gaunt, its ribs pressing through its rippling pelt, eyes flashing as its head moved sharply, watching them, then the horses. Not wanting to turn away, Bataar inclined his head at Shaza. The two of them moved in tandem, nocking arrows and pulling bowstrings taut. Maybe they could distract the gryphon, giving Tarken time to get his little brother away. The ponies whickered, breaking the quiet.

Up ahead, Chugai asked, “Find something?”

His older brother thumped him on the back of the head. Tarken whispered, “Shut it. They’re hunting, you’ll scare their quarry away—oh, Spirit.” Tarken’s eyes went wide, and he dropped the berries he’d been eating. They spilled across the dirt, garish orange on red.

Erdene screamed and tore into the air, circling above the field as the ponies fled, veering off across the stream.

The gryphon moved quickly. It reared on its hindlegs, flapping its wings, and leapt. Suddenly hulking over Chugai, it craned its neck down, beak inches from his head, breath stirring his brown hair. It put one paw on Chugai’s head, the other on his shoulder. Bataar and Shaza loosed their arrows—they glanced off the gryphon’s shoulder. Tarken’s bow was on his horse, so he threw his bag. It missed, splashing into the water.

Chugai only had time to squeak, like a mouse. Snap snap snap, a sound like so many sticks breaking, a little boy crumbling. The gryphon’s beak opened and shut around the broken body. It threw its head back, swallowing him whole.

Bataar watched bonelessly as Chugai’s soul swirled out through the gryphon’s nostrils.

He told himself don’t look. But he had to watch, to bear witness to that moment when the gaping mouth of Preeminence at the precipice of the sky drank in Chugai’s soul.

“No!” Shaza shouted, firing more arrows. “Tarken, move!”

The gryphon didn’t flinch as barbed heads sank into its flesh. It circled, eyes gleaming, and batted Shaza away with a crunch. She fell on her back, the front of her tunic torn. Scarlet bloomed across the fabric. Her ragged gasps told Bataar she was still alive, for now.

Tarken collapsed to his knees as the gryphon neared. Bataar tried nocking another arrow, but his fingers were clumsy. His ribs constricted, tight around the hollowness in his chest. Bile burned in his throat, and his eyes stung as his quiver spilled into the bank.

The gryphon’s paw thumped against Tarken’s face. He wobbled, whimpering, a thick red line welling across his nose.

The gryphon tilted its head curiously.

Bataar thought of the oath he’d whispered to Tarken, when they camped together last year; no longer just friends, but bloodsworn brothers. Memories of skating on the Lugei river in the winter came to him. He remembered laughing so hard his sides ached when Tarken fell and slid into a snowdrift.

Numbing powerlessness overcame Bataar, loosening his grip, making it hard to stand on shuddering legs.

“Tarken!” he yelled. Run, fight, do anything.

Everything was happening too quickly, a smear of motion and choking terror. He didn’t want to cry, but the world was already blurring.

An arrow shot into the dirt beside the gryphon’s talons. Bataar couldn’t tell where it had come from. The gryphon spun away, leaving Tarken gasping, the front of his breeches darkening. The wind carried Qaira’s smell, honeyish, like edelweiss flowers.

Bataar reached uselessly for his spilled quiver.

The ribbons in her horse’s mane flashed a rainbow of color as she gripped its bridle. “Shhh, shhhh,” Qaira whispered. She dropped the reins and raised her bow.

Bataar had once watched her split one arrow with a second, bursting them through the back of a target the older boys had put up, but he’d never seen her kill anything. Her hands didn’t tremble as she loosed an arrow toward the gryphon’s face. It deflected off its beak. The gryphon screeched, loud as a peal of thunder.

They were all going to die like Chugai.

Bataar didn’t want to meet Preeminence’s gaze, to watch its horns and teeth and black eyes as his soul joined it in the sky, but he’d face death, if it meant the rest of them lived. The blade of his knife was short and straight, tapering to a hatchet-point. He unsheathed it and stumbled forward, uncoordinated with panic. With both trembling hands, Bataar sank the blade into the gryphon’s flank, sliding it between dense quills.

“Take your sister and Tarken! Get out of here!” he screamed to Qaira as the gryphon’s beak thrusted toward him.

Bataar pulled the knife out and fell onto his back. He scrambled through the dirt, kicking the gryphon’s chest. His pulse pounded as claws raked across his face and burned down, over the top of his chest, into his shoulder. More of Qaira’s arrows sank into its body. Shadows oozed from the wounds. Bataar put his dirty fingers in his mouth and whistled. Erdene swooped down, her talons slicing through black feathers. Smoke seeped out and dissipated in the air. Bataar blinked in confusion, vision fading on his right side as something warm and wet flooded his eye.

There was something hypnotic about its eyes; they made Bataar want to freeze up and pee himself, like a mouse cornered by one of the camp cats. But he wasn’t prey. Stabbing again, his blade pried some of the huge feathers loose. His vision was obscured by blood, tendrils of smoke, and plumage floating in his face.

He blinked, and as it cleared, the gryphon’s bare purple skin came into view. The claws on one paw slashed at him. Bataar ducked away, squeezing himself down toward its midsection. He jammed his blade into the gryphon’s stomach. Hot droplets hit his face. It bled. It could be killed.

Qaira yelled his name. Her gentle voice had never sounded so hoarse.

The gryphon curled its underbelly back. A fervor overcame Bataar. His hands moved on their own, faster than his mind could think. The knife sank in and out of the muscles on its throat as its beak snapped toward his face. Blood ran over his hands, coating his arms down to the elbows. His fingers turned raw, palms splitting and chafing against the knife’s hilt. He recognized Erdene’s brown feathers on the arrows Qaira fired now, from his spilled quiver. With a scream, Bataar plunged his blade into one of the gryphon’s yellow eyes.

Its soul seeped out of its body, pulling close and snarling in Bataar’s face. The gryphon’s spirit was shimmering nothingness, but it caressed his skin like fevered breath before it was swallowed up. Its hunger smelled sour, the same desperation and fear that roiled through Bataar. He kept stabbing even after the gryphon’s weight collapsed on top of him. He didn’t stop until Qaira pried the knife from his fingers and groaned, struggling to roll the gryphon’s body off his. She didn’t vomit at all the blood. She didn’t cry or shake. He stood dizzily, throwing her hands off when she reached for the scratch across his face. He wiped the blood out of his eye, his vision turning red again in seconds.

“I’m fine.” His voice scratched, clawing its way out of his throat.

Near Tarken’s stunned body was one of Chugai’s shoes. Bataar limped forward. Inside was a little foot. Bataar had only had a few bites of dried meat to eat in the last several hours, but it bubbled in his stomach as his eyes fell on the white bone protruding from bloody flesh.

“Let me help,” Qaira said softly.

They worked together. Qaira wrapped wounds using clean strips torn from their clothes. Shaza moaned, eyes unfocused as Bataar hefted her onto his shoulder and laid her across her sister’s horse.

“We need to get her to Boroo quickly,” Bataar said. She’d already lost a lot of blood. The shaman wouldn’t be able to do anything if Shaza died before they could get her to camp.

Qaira whispered gentle things to Tarken as she helped him stand. “He was embraced by the Preeminent Spirit. I felt it,” she said, voice full of kindness.

Her words were well-meant, but Bataar had seen it, the moment Chugai’s soul disappeared. The universe had swallowed him with blank eyes. Bataar tried to keep from quivering. He couldn’t tell Tarken, not now, or ever.

Tarken’s voice cracked. “My brother. His body, I can’t leave it.”

“I’ll come back for him,” Bataar swore.

He gave Tarken the wrapped shoe to hold. Tarken slotted his other fingers through Shaza’s limp ones and walked. Qaira rode, steadying her sister against her. Bataar tried to staunch his own bleeding, so the red seeping through his tunic wouldn’t drip and create a trail. Every step made his head spin, but he waved away Qaira’s offer to ride with a stiff upper lip. They moved slowly, in silence punctuated by groans and stifled sobs.

Twilight was smoldering, coloring the sky in melting pinks when relief twinged in Bataar’s chest. Shaza’s shoulders still rose and fell in shallow breaths, and their camp grew in the distance.

Ignoring the gasps and concerned expressions as they entered the circle of tents, he took Shaza off the horse and laid her down near the cookfires. Qaira ran to get the shaman. Bataar stood in a daze as Boroo worked. He let his mother fuss over him, dabbing his face with a damp cloth. Across camp, a woman cried, clinging to Tarken—his mother. Chugai’s shoe dangled in her hand and fell. She looked down, her ragged sobs turning to a keening wail.

“Thank Preeminence,” Bataar’s mother whispered, gripping him with desperate fingers, squeezing his uninjured shoulder like she was reassuring herself he was really there.

* * *

When night fell, Bataar led the men to the gryphon’s carcass. His wounds burned as they skinned the pelt by the light of a torch, revealing purple flesh underneath. Chugai is inside there, he thought, as the men dressed the kill.

Back at the camp, they burned Tarken’s little brother on a funeral pyre. His body reeked like something rotten as tongues of flame lapped up at blackness.

“You did well,” Shaza’s father said, clasping Bataar’s shoulder, careful around the bandages. The hardened poultice itched.

Shame settled, iron in Bataar’s gut. He hadn’t brought them all home. The horses were gone with the hares, and the gryphon that had murdered Chugai was no feast, its ribs bulging through its skin. So little meat clung to its hollow bones, as if most of the fat and muscle had burnt up in the tendrils of smoke that had curled off its wounds. Every bite was dry and charred, a mouthful of ash.

Boroo, a shaman old enough to be a grandmother’s grandmother, stood near the fire, chanting into the blaze. Families shuffled close to Tarken’s mother, offering flat condolences. Her gaze looked beyond the feathery pelt hanging on a rack near the fire, searching for something far away, past their world and gone forever. Tarken stood frozen at her side, as still as he’d been when the gryphon attacked. Bataar turned away from them, looking out at the emptiness, the stoic mountains and distant stars.

The face in the sky never slept. Some creature was always dying, sustaining the Preeminent Spirit on a banquet of souls. He pretended not to see, and tried to convince himself it wasn’t beautiful.

Soft steps rustled dry grass. Qaira stopped beside him, close enough their fingers could brush if he flexed his. Her sudden gasp made him instantly alert.

“What is it?” Bataar’s hand shot to his knife in its sheath.

He scanned the darkness, following her line of sight in the sky. Shapes came into focus just as the screeches reached camp. Bataar took a breath and held it as the shaman’s chanting quieted. Tarken’s mother shook. Some other women whispered prayers.

Qaira stood firm, but if the wind blew, she might have fallen like a leaf. Bataar clenched his jaw, waiting. A few heartbeats later, the swarm of gryphons passed over and disappeared. When their shrieking faded, Bataar finally let himself take another shaky breath.

“Strange,” Boroo muttered, as expressions on the faces around the pyre relaxed.

Bataar flexed his fingers, brushing Qaira’s. Every living thing had a soul, had a place in the divine web of things, but no other animal Bataar had seen moved like shadows come to life. His hand twitched.

He turned away, leaving Qaira stranded at the edge of the darkness. He wouldn’t turn around to check if that face suspended in the canopy of night watched her with a familiar hunger.

All around, people were looking at Bataar, really looking. He’d fought a gryphon and survived. More than that, he’d killed it. He studied his palms, wondering what people saw when they looked at him now. Steadying his breathing, he tried to still his fingers. How many times would he have to scrub his skin before all the traces of the day disappeared?

* * *

That night Bataar woke up covered in sweat, staring around the unlit tent in a haze. The iron stove looked like a crouched body with a long neck, and the furs on the walls seemed alive. The fire had died. Nausea rolled over him, but his stomach growled at the smell of burned fat. Pain had ripped him out of dreamless sleep, as sharp as the claws that had maimed his face.

He was on fire. He was dying. Bataar couldn’t call out as the fever burned through his body.

In the moonlight coming through the crack in the door, he found his mother’s shape. He took a few ragged breaths. The poultice itched, especially his chin, and the front of his tunic was plastered to the wound on his chest, but he couldn’t scratch it. He just stared up at the roof, waiting to face Preeminence.

The shadows never took shape. Morning came. The next day, his fever broke.

* * *

His scabs scarred, enduring in twisted knots across his face, neck, and chest. As the years passed, people began to say Bataar’s dark hair looked inky, like gryphon feathers. They said that he had a severe, serious face, that his scar meant he was gryphon-marked.

Gone was the boy desperate to prove himself. Now, when his enemies saw him, they were afraid.

SPRING, 357

Sixteen-year-old Ramzi led the forces that conquered Keld in 336. The Dumakrans occupied the holy city for five bloody years.

—The Southerner’s Child King

A gust of wind blew through the entrance to the sanctium. Nohra stopped scrubbing at the handwashing fountain and looked up, catching a glimpse of blurred feathers and massive wings as her aunts landed their pegasuses on the steps outside. Bellowing whinnies turned into keening falcon shrieks, cracking through the cool morning air. The pegasuses’ yellow eyes rolled, and their sharp teeth bit down hard on the metal in their mouths, steel-shod hooves lashing stone. Nohra’s aunts tied them off and tightened their blinder hoods. Finally, the feathers on the pegasuses’ fetlocks and necks settled.

Her aunts brushed past, not bothering with the crowd gathered outside or a glance her way. Their family’s insignia glittered on their feather-steel breastplates. The royal crest, a rearing pegasus, signaled them as her father’s Harpy Knights, but everyone in the capital would recognize their faces even if they were wearing rags.

“Lend me a wing, little bird,” her mother said. Turning from her aunts’ retreating backs, Nohra walked deeper into the sanctium and took her mother’s arm.

Nohra should have outgrown pet names by now. She was tall enough to meet her mother’s eyes without straining her neck up and hopping like one of the sparrows in the palace courtyards. But hardly a moment passed when Nohra wasn’t flying, so little bird she was.

Seeing the other pegasuses made her miss Mercy. Her colt was as black as a raven’s wings, as wild as wind. The trainers up in the mountain were breaking him now, making him obedient and rideable like the ones in the stables she’d learned on.

A hip and elbow jammed against Nohra’s back.

“Have you had a good look at his latest acquisition?” Merv asked the concubines. She glanced disinterestedly down at Nohra, pretending to be surprised to find her at the end of her sharp elbow.

Merv Attar, the zultam’s first wife, was Dumakran-born and older than Nohra’s father. She was gossiping about the new girl, young enough to be the zultam’s daughter, with red hair and freckled skin.

“She’s Aglean,” another concubine whispered to Merv, looking pointedly at Nohra’s mother. Merv Attar arched a perfect eyebrow, her lips twisting. If they hadn’t been in the prayer hall already, Nohra would have threatened to wipe the sneer off the queen’s face.

Merv had good reason to be a jealous bitch. It was no coincidence that the blue tile covering the walls matched Nohra’s mother’s eyes. This was Thora’s Sanctium, erected in her name. It reflected her beauty back in gilt-edged arches and pillars. Thora had come from South Aglea to Dumakra when she was scarcely older than Nohra, claimed in a skirmish as a gift for the zultam, or sold by her parents. She never spoke of it. Her Dumakran was still accented fifteen years later, and her beauty hadn’t waned. Her skin was milky and easily burned by the hot sun, and her hair fell in pretty waves like spun gold. Nohra knew she was only a tarnished approximation of her mother.

“Chin up,” Thora said, tapping the space between Nohra’s shoulder blades. She didn’t seem to hear Merv’s mocking laughter, or maybe she just didn’t care.

Merv and Thora, the two imperial queens, always traveled with concubines, princesses, servants, and eunuch guards. But their retinue only followed as far as the prayer hall in the inner sanctium before taking their places in the outer ring. After fussing with Nohra’s tiara, her mother drifted away to the middle of the room.

A chill slithered through the sanctium, and the floor in the innermost circle was cold on Nohra’s bare feet as she hurried to her spot with her half-sisters. Hanging incense burners sparkled at the cleric’s dais. Nohra breathed in the smell of burning olive leaves, familiar and warm. As she knelt, the natal-day rings encircling her fingers tapped the smooth tile. At fourteen, she’d long since run out of fingers for new rings; now four fingers had two bands each.

Safiya appeared like she always did, a sun suddenly blinking to life in the room. “I’ll race you to the training yard after the ceremony,” she whispered conspiratorially, knocking Nohra’s shoulder with her own. “It’ll be a good warmup. Captain Mady says he’ll teach us grappling. They say he fought some of the best Utasoo wrestlers at the Blood Rhah’s wedding and won.”

Nohra snorted. “Who says?”

Saf beamed. She always thought everything was funny. Her tiara glittered under the light of the swaying lamps, resting on her dense black curls. Nohra’s own was itchy in her brown hair.

Like Nohra, Safiya had been born a concubine’s daughter, but her mother hadn’t become a queen. Saf was the firstborn princess, their father’s oldest child and his favorite, probably. She liked playing with swords and gaping at pretty concubines, and everyone loved her. For more than a year now she’d been studying history, alchemy, medicine, mathematics, and fine arts at the Conservium, and was infuriatingly good at everything.

Nohra had always been jealous of Safiya, but she was impossible to hate, except maybe when they fought. It was annoying that Saf hardly broke a sweat on the training ground. In the last few years, Nohra had grown taller and heavier than her half-sister, which made her slower, even if she had the longer reach.

“Don’t tell me you’d rather have dinner with Grandmother?” Safiya raised an eyebrow. “Like a polite little lady?”

She wouldn’t. “I’ll come fight.” The bruises would heal, the scabs would scar, and adrenaline always tasted sweet. Of course, her maid Darya would gasp in the baths, where the clouds of steam couldn’t hide the purpling battle marks, but Nohra didn’t need her approval.

Safiya smiled. “Then we’ll have dinner with the men in the guard house.”

“I know you don’t care,” Nohra grumbled, “but I won’t eat what they’re having.” The soldiers garrisoned at the palace were foreign-born and impious.

“Oh yes, ‘I profane my mouth on feathered flesh’. Don’t worry. We’ll send someone to fetch you something else from the main kitchens.”

From the smell of cooked chicken alone, Nohra would picture pegasuses, gryphons, and the Goddess’s winged daughters, nausea stirring her gut.

At least her manners wouldn’t be criticized between each bite. Nohra would as likely meet her end in Grandmother Himma’s stuffy quarters, to the tune of music and etiquette lessons, as she would on the training ground.

“You know we could sneak out early, before Father notices,” Safiya said, nodding toward the doorway. Around them, their half-sisters, girls with pudgy cheeks and tiaras askew, knelt with their faces screwed up in concentration.

Nohra shook her head. “You might try to learn something from the Godsbreath.”

Safiya looked like she wanted to pinch Nohra’s face. “It’s adorable you believe in all this.”

“Saf!”

“Really, you’re such a good girl.” Safiya laid a hand on her heart. “May the Goddess have mercy on my unworthy soul.”

“She won’t.”

Nohra relished the calm of the inner sanctium. She found strength in her faith, more than she found in her father’s armory or in getting her ribs sprained by her sisters in the training yard. If she prayed hard enough, she would wear divine armor no weapon could puncture, and peace would be her guiding light.

Unlike Safiya, she didn’t fight because she enjoyed it. Nohra fought for Father, for her country, and for Her—Paga, the incarnation of peace.

Their father knelt on the stairs to the cleric’s dais, surrounded by his sisters in their gilded armor, his four Harpy Knights. He was separated from full view of the crowd by an ornamental grille, but all of Kalafar clamored for a rare glimpse of him. Through geometric cutouts in the metal screen, all that was visible were fragments of his white turban and the dark brown hair at the base of his neck, his shoulders that to Nohra had once seemed wide enough to block out the entire sky.

He didn’t turn, but he must have felt her watching. He beckoned. “Safiya, Nohra, to me.”

Curious eyes bore holes in Nohra’s back. It was special to be signaled out by the man everyone knew was Goddess-blessed. Even if he was their father.

For a second it was like they were little girls again, going with him to watch falconers fly the royal birds and have supper in his private quarters, back when they were his daughters instead of his guards in training.

“Princesses,” Clemiria greeted, her voice clipped.

Their aunt surveyed them with narrowed eyes. Only last week, Nohra’s father had crowned Clemiria queen of the Sister City across the desert. Soon she would leave to take up her throne, and her lion-headed sword Queen of Beasts would need a new wielder. Safiya was the obvious choice. She was nearly seventeen and as skilled with a blade as any of the Rutiaba Palace guardsmen.

It was Bleeding Edge, the sickle-staff, that Nohra wanted. Her eyes fixated on its red crescent blade, strapped to Aunt Farrah’s back. Nohra would have to train hard to beat out her sisters and have a chance to stand next to Saf at Father’s side. Any daughter who could ride and fight could become his soldier, but only four could become his Harpy Knights.

Safiya’s smile was saccharine as she inclined her head with false politeness. Nohra tried not to scowl or trip over anyone’s hands.

Now flanking their father, they crouched again. Nohra’s knees were beginning to ache, and the cold tile raised goosebumps on her arms. The zultam didn’t say anything, didn’t smile or acknowledge them. But joy blossomed, thick in her throat, as if the moon had chosen to shine only on her.

Ahead, the hems of the priestesses’ robes puddled on the floor of the platform. Paga’s priestesses wore veils trimmed with coins. The other women wore hoods and half-masks: these were Nuna, the chaos incarnation’s silent daughters. They wouldn’t sing Her praises until the Long Reconciliation began, and the Goddess was of one mind and body again. Immaculate and whole.

A hush fell over the murmuring crowd as the cleric cleared his throat. He wore unadorned gray robes, nothing like the women’s costumes. His face was unlined, beard steely and cropped short. The arms of the young boy holding the Godsbreath wobbled under the weight of the illuminated tome.

“Before man, the Goddess carved bodies from the bones of the first demonking,” the cleric said, picking up from his marked page.

A god’s soul was too large for just one body, so when the Goddess took a mortal shape, She tore Herself in two: peace and chaos, life and death, Paga and Nuna. Nohra remembered looking up at the frescoes of the incarnations’ blank faces as a child. Even before she knew their names and the stories of the godswar, she’d already thought they were perfect, the queens of her dreams and nightmares.

“During the first godswar, the Goddess’s Harpy daughters fell, and the last demonking was chained in servitude, harnessed as an agent of havoc.”

Like in lessons, it was difficult to focus. Especially because Nohra already knew these stories, had memorized the words. She tried not to be distracted by the whispers from the back of the sanctium, the fly buzzing around the red water from the Heartspring, or the light refracting off the ornaments on her father’s turban. One of her aunts cleared her throat.

“A final time of turmoil will usher in a long and peaceful era, the Long Reconciliation.” The cleric’s words rolled over each other in a soothing cadence, like a tired song.

Nohra could go to the private sanctium at the palace after she trained with Saf. It didn’t have a magnificent skylight, but its domed roof was decorated with images of bat-winged Nuna in her cloak of shadows and stars, and Paga, resplendent with Her white hair, red skin, and scythe. And there were fewer distractions there.

One of the priestesses held cupped hands overflowing with red water close to Nohra’s face. The half-veil covering her nose and mouth meant she was one of Nuna’s. Sweat sheened the priestess’s forehead, though Nohra was still shivering. The woman watched the room, gaze flickering between the doors to the inner sanctium, the zultam, and his Harpy Knights. Her eyes were light, a honey brown Nohra hadn’t seen in the capital. Some people in the north had features like that, where Dumakra brushed South Aglea.

Nohra’s heart hammered as she took an irony gulp of the water from the priestess’s hands. When her lip awkwardly brushed the woman’s fingertips, the soft touch fanned flames under her skin. A swarm of bugs fluttered against the walls of her stomach. Every nerve in her body thrummed, just like when Fahaad—a servant she was only friends with—had stolen a kiss from her behind the stables. The priestess met her eyes, holding her gaze; for a moment, Nohra could have died of embarrassment.

Then the priestess’s pupils burst in sudden panic. She rushed forward, the tip of a blade poking out from her sleeve. Nohra’s aunts hadn’t even looked up, and the cleric hadn’t paused his reading, but Nohra stood, pushing in front of her father.

“What are you doing?” he said as Nohra crashed into the priestess.

“Down with Dumakra’s heretic emperor!” The woman’s hissing voice was muffled by fabric.

Shouts exploded around the room. Concubines and viziers’ wives screeched, servants screamed and children wailed. Nohra grabbed the assassin’s wrists, pinning one arm behind her back. The other one wriggled free. A hot ache bloomed in Nohra’s stomach as the knife slashed across her dress, splitting through silk. A strangled sound, half-gasp, half-groan, escaped her lips. She gritted her teeth, trying to keep the pain contained, her blood pattering as it dripped onto the marble.

The rings on Nohra’s knuckles caught the priestess in the jaw. The woman reeled, her eyes unfocused as Nohra wrestled her down onto the floor. The cleric, mouth agape, stepped away from them as they rolled on the ground. The knife fell from loosened fingers, hitting every step on the dais and skittering into the crowd.

The Harpy Knights formed ranks around the zultam. One of Nohra’s other aunts raised her crossbow, Covenant, aiming at the assassin. “Move, girl,” Clemiria ordered.

Safiya lunged forward, hands outstretched to pull Nohra back to safety. The screams coming from around the room were dizzying. Nohra went lightheaded as she touched her stomach, hoping to stanch the bleeding. With a grunt, the attacker kneed Nohra in the abdomen and broke free. Something glistened under the wrist in the assassin’s other sleeve—not a knife, some kind of apparatus, with a dart jutting out. Nohra winced, stumbling to her feet. Her palm came away from her stomach painted crimson.

Paga was here, in this sanctium, in the sun spilling through the skylight, in the olive leaf incense, in Nohra. Peace was fragile and fissuring and sprinkled with Nohra’s blood.

Aunt Clemiria wrestled Covenant from her sister and fired a bolt from the crossbow just as the assassin raised her arm, aiming her wrist at the zultam. Nohra wrenched the woman back. The dart arced off course. It shot too high, flying toward the sky window instead of Nohra’s father.

The woman’s head cracked against the marble step, light draining in an instant from her honey eyes. The crossbow bolt hit Nohra in her shoulder. Her body jolted. The noise of the crowd faded to a distant drumbeat, an ache pulsing where her arm joined her torso. Nohra didn’t see Paga’s featureless face in the throng; her eyes landed on her friends, Fahaad and Darya, at the room’s fringes with the other servants, their expressions contorted with concern. Her mother was pushing through the crowd, but Nohra was already in Safiya’s arms, letting her sister help her limp toward the outer sanctium.

The decorative divider that separated the zultam from the world wobbled and fell with a cymbal clang, and suddenly sound flared back, ear-bleedingly loud.

“This is bad,” Nohra whimpered. “I fought in the sanctium. People go to hells for that.” The house of the Goddess had been soiled by blood and death, but still beams of golden sunlight shone down.

The hard line of Saf’s mouth softened. “You’re not going to hells.”

Nohra took a trembling breath, stumbling. “Am I going to die?” She wanted the truth, but she knew her sister wasn’t above telling a lie in the sanctium.

Safiya attempted to smile, lips twitching. “Of course not. You’ll be in fighting shape in no time.”

Nohra tried to respond, but her words came out gurgled. She could tell Saf’s smile was hollow because her dark eyes were shiny with unshed tears. Nohra groaned. Everything hurt.

“Nuna,” Safiya swore. “It’s—you’re fine. It isn’t—you’re going to be okay. Paga’s holy ass, you’re so stupid, Nohra.”

Saf had learned medicine at the Conservium. She’d even shadowed the royal physicians. If she was crying, Nohra was doomed.

She prepared for her vision to flood black. Instead, she found herself sinking into white bed linens and the smell of lemony soap.

* * *

The cleric’s bed was surprisingly soft. He smiled patiently as Nohra apologized over and over for bloodying the bedclothes. The court physicians had dulled the pain in her shoulder and stomach with numbing salves and plied her with a red tincture that made her feel deliriously at ease.

“You should’ve stabilized the shaft of the bolt and cleared out the inner sanctium instead of moving her,” the physician scolded Safiya, who had insisted on watching as the broad-head was removed from Nohra’s shoulder. When Nohra woke toward the end of the surgery, through the fog of the opium, she remembered seeing her sister gawking like she was watching a toad being dissected.

“Yes, maven,” said Safiya, sinking a little at the doctor’s chiding.

“We’ll prepare a room in the palace infirmary, Your Majesty,” the doctor told Nohra’s mother.

Thora’s voice was still shaky. “Thank you, Adeem.”

Adeem Aden was a young man, but his beard had started graying when Safiya and Nohra began training to be Harpy Knights. He continued, “If it isn’t a stab wound, it’s a broken wrist from a fall, glass in her knee, a dog bite. Better than a broken neck”—he paused, scrunching his nose—“I suppose.”

“Everyone’s worried. I should tell them you’re alright,” Safiya said, ducking out of the cleric’s room, clearly glad to be out of there. All the fun had ended when they’d finished sewing Nohra up.

Nohra looked to the physician. “I can go riding, can’t I?”

He frowned. “No.”

“Flying?”

He looked unimpressed. “No, and if one of your sisters tries to sneak you out, she’ll find herself in a bed beside you.”

Nohra slumped. On bedrest, she couldn’t practice with Saf in the training yard, fly pegasuses at the stables, or even hobble to the palace sanctium to pray. She’d have to work twice as hard to become a Harpy Knight now, before one of her sisters stole Bleeding Edge. Nohra didn’t care about Clemiria’s lion-headed sword, but she’d dreamed of the sickle-staff for as long as she could remember. Its feather-steel flashed red like the Goddess’s scythe, jeweled with rubies dark as welling blood.

She pouted. “Then what’s the point of living?”

The doctor blinked unsympathetically. “Learning. Your tutors can visit, so your education will continue. Let this be a long-needed lesson in recklessness.”

“But—” If she hadn’t intervened, someone could have died. If not her aunt or her father, the zultam, then someone else among the innocents and courtiers gathered to pray. Everyone should be celebrating her! This was basically her first act as a Harpy Knight. There’d been a whole week of feasts when her stupid half-brother got circumcised.

“The assassin’s dart was tipped with a neuromuscular blocking agent,” the physician said. “If it had struck its target, paralysis would have afflicted the lungs, resulting in respiratory failure.” It was as close as he was likely to get to outright praising her. “You should have alerted your father’s guards when you noticed, not charged at an assassin bare-handed.”

When Adeem Aden had finished admonishing her and departed, Nohra surveyed her ugly stitches. Her aunt’s crossbow bolt had cut through to the other side, but a part of the broadhead had lodged itself in the meat of her shoulder. The jagged wound on her stomach was hidden under a plaster dressing and layers of bandages. Gingery turmeric wafted up from the muslin wraps. ‘What a lucky girl,’ the doctors had said as they poked at her. She was probably the unluckiest girl in Kalafar.

Tearing her gaze away from the wounds, Nohra sighed. Sighing hurt even worse than talking. Her mother perched at the foot of the bed, eyes red-rimmed, tear tracks staining her cheeks. In the light of late afternoon, even her mother’s alabaster skin was bronze-touched. Nohra’s blood was matted in her hair and smeared across patterned brocade, spoiling the fine fabric of the robed dress and white skirts.

“I thought I’d lost you,” Thora said. A sob caught in her throat.

The cleric had given Nohra his necklace as something to hold before the anesthetic tincture had gone into effect. She’d clutched it so tightly it had left an impression of flowy script on her palm. Now she ran her fingers over the words engraved on the flower-shaped pendant. Peace sows complacency, Chaos begets order. In her poppy-addled head, Nohra couldn’t seem to understand what the words really meant. Something about how there was good and bad in everything?

By a small window, the cleric tilted his head, his gaze aimed at Thora’s flat belly. “A son?”

She balked. “How could you know?”

“Paga put the question in my head.” When he smiled, his straight teeth and easy grin made Nohra flush. Even with strands of silver threading through his hair, the cleric was handsome.

But what had he said? A son? A brother? Nohra’s surprise was a blade of ice cutting through the fog. She studied her mother’s profile, that small smile, like Thora had already known she was having a baby.

Most of the women in the harem were only permitted to bear the king one child, like Safiya’s mother, who had retired to an estate outside Kalafar. And Dumakran court wasn’t kind to boys. Nohra had grown hardened to her half-brothers crying, stuffed away in private wings of the Rutiaba Palace until they were weaned and sent off, exiled to live as wards in distant parts of the country, or even farther. But Nohra’s mother was Father’s favorite. If she had a son, he would be raised as the next zultam. He’d become the crown prince, Nohra was sure of it.

Thora took Nohra’s hand and squeezed her fingers.

“I’ll ask Paga for an easy pregnancy,” the cleric said, “and a quick labor.”

* * *

For the next seven months, Nohra held onto those words the way she’d clung to the cleric’s necklace. But it turned out even the incarnation of peace and mercy could be cruel.

Nohra was almost fifteen when her little brother was born. That same day, her mother died. The medicine mavens frowned sympathetically when they gave Nohra a box to take to the palace in the mountains, to put in the tomb with all the other dead queens’ hearts.

WINTER, 367

Gods of granite do not crumble when men die and empires fall.

—The Supreme School of Thought in Xincho

The siege would end before the night did. Bataar stood behind the palisades, watching the battering rams and projectiles meet the wall with earth-shaking sound. Smoke hung over the last stronghold of Choyanren. The city wall surrounding Tashir had once glistened. Now, the stone was streaked with gore, dented from projectiles thrown by Bataar’s catapults. White flakes of ash rained down, collecting on the backs of their horses. Hot sand and boiling water hissed as enemy guards on the walk defended against Bataar’s siege towers. The night exploded in light as a cannon fired on one of the siege machines. A torch fell, and fire spread. Burning wood popped and cracked, splitting apart like logs in a stove.

Bataar nearly fell from the saddle when one of the battering rams finally breached the city wall, sending up a cloud of dust and debris. At the horses’ hooves, Tarken’s dogs salivated and snarled. The cavalrymen swirled in formation, waiting for the opportunity to storm in as Shaza and her archers picked off guards on the wall.

“Watch the longbowmen in the crenels!” she shouted. “If you lot die, I’ll pack your ashes into gunpowder.”

High above, sabers clashed. The sound of metal rang through the night like talons raking steel. A flash of gunpowder illuminated the dirt-smeared faces of soldiers as a cannon ball pounded out of an iron bore, wedging into the wall. Two more shot out, the sound like a heartbeat.

“Whoa, whoa,” Bataar soothed, wrestling with the reins on his gelding. High above, Erdene screeched as she wheeled through the smoke. Her feathers had darkened over the past twelve years, her body a golden-brown gash in the starless sky. Bataar whistled for her just as a firework exploded in the air above Tashir.

“What’s that signal mean?” Shaza yelled. Her fingers dripped with red as they pulled away from a slice across her cheek.

Tarken grimaced as his dogs howled at the explosion. “Bataar?”

In the sky above the city, a spray of gold shimmered in the air, like a flower blooming among white stars. The second explosion was red. At the third pop, an ocean spray of blue erupted across the smoke-clouded sky, and the Choyanreni on the walls laid down their arms.

Hollowness settled in Bataar’s gut as snow began falling.

Someone shouted, “The emperor is dead!”

* * *