8,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: via tolino media

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

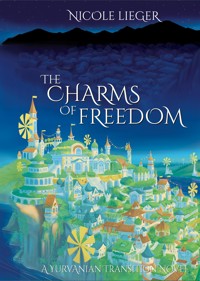

"Enchanting Visions"

Windmills, community spirit, rooftop gardens – that is what young magician Enim knows. But when he travels out to the mountains, misery hits him in the face. Before he knows it, Enim gets adopted into a found family that is determined to take on the powerful owners, free the miners, and bring on a good life for all. The exact steps to saving the world are still a little unclear. But that won’t stop anyone from rushing ahead!

Between the politics of the capital and the instruments of magic, a tangled love-tie and a popular uprising, their snug group of orphan kids and the inner strength to ban a demon – will they finally make it happen?

“An inspiring tale full of gentle humor, vibrant zeal and ludicrous optimism.”

“Perfect for fans of Becky Chambers, Ursula K. LeGuin and Studio Ghibli.“

This book is for you if you like:

-) a fantasy world full of conviviality

-) upliftingly stubborn activism

-) the quiet wisdom of mountains

-) a vision of children growing up free

-) wealth beyond jewels

-) small furry charmers

-) fantastic challenges to common thought-patterns

Other books in this series: The Starlight of Shadows

(German editions: Der Zauber der Freiheit / Schatten aus Sternenlicht – Die Yurvanischen Wandelromane)

These Yurvanian Transition novels can be read independently, in any order.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

The Charms of Freedom

A Yurvanian Transition Novel

Nicole Lieger

To those who save the children

A background-chitchat-glossary

for the world of Yurvania

is available on my website:

nicolelieger.eu/yurvania

Table of Contents

The Charms of Freedom

To those who save the children

A background-chitchat-glossary

Table of Contents

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

Thank you for reading! :-)

THE STARLIGHT OF SHADOWS

Imprint

Ready for more?

1

Windmills lazily turned their white sails over a jumble of rooftop gardens. The Transition had grown gracefully into the charming playfulness and pompous self-importance of the old mansions. It covered them with greenery as tangled and vibrant as the patchwork of families and friends now inhabiting the stately homes. Ripening fruits gleamed on turrets and archways, and blossoming vines wound around a balcony where a few complacent hens clucked down at the people far beneath them. The morning sun came to bathe Varoonya in pale and glorious gold.

But behind thick velvet curtains, a gloomy twilight reigned. Muffled silence filled the hall, and the ancient walls seemed to run up endlessly toward the canopy of their vaulted ceiling. Enim squinted up into the shades. From a box hung with ornate tapestries, the expressionless faces of five examiners looked back down at him.

Enim cleared his throat.

There was nothing for it now.

He turned back toward the elaborate design laid out on the floor and checked again. Crystals of blue and purple blinked at him between threads of finest glass. Enim couldn’t see a single flaw.

He raised his wand, his eyes narrowed. In that moment, the world disappeared to him. Enim knew nothing now but the runes in his mind and the flow of magic in his veins. Full and round, the first vowels rolled off his tongue, ancient words of power, intoned with a perfection reached through years of relentless practice.

With a deep, secret rustle, the lines of a pentacle began to glow, spreading their fiery gleam across Enim’s face.

* * *

}}} Kaya crouched behind low shrubbery, hidden in the shadow of the looming mountain. It was dark all around the mine. Black clouds scurried across a thin sickle moon high above, driven by a cold, gusty wind.

Lhut came up beside her, silent as a ghost, and gave her a short nod. So the path was clear. Kaya spied out from behind the branches. A guard had passed just a moment ago. It was now or never. She checked back with Lhut, then eased through the branches and swiftly made for the mine, without stopping and without looking back. Lhut followed close behind.

They did not halt once they were inside. They knew the path well enough. They had been toiling here for years, after all, day after day. Down they went, along the tunnel and down again, turn after turn into the maze of the mine. Finally, Kaya stopped. Almost there. She listened closely, then peered around the corner.

‘Yes!’ Kaya’s heart jumped.

Everybody had come. They really had come.

Before her, where the tunnel broadened out, the figures gathered in the light of a single torch were little more than dark shapes and flickering shadows. But Kaya had no doubt. These were her people.

‘We have come tonight, all of us,’ she thought. ‘Exhausted as we may be after shifts in the mine. Frightened as we may be after veiled threats, and more and more naked threats. We have come, in spite of it all.’ Kaya smiled a proud and wretched half-smile, as did many miners.

“Well, then.” Kaya’s voice was low and intense as she took the hand of the man next to her. She gave Lhut the other and the circle closed all around, people clasping each other’s hand in a solemn gesture of strength and determination.

In the silence of that rite, they heard it coming.

A low rumble at first, a sigh of stone somewhere deep in the mountain. An aching and moaning of slabs—and then, splintering wood and a crack in the ceiling.

Everybody jerked back. A scream tore through the air. Black figures began to run for the exit, stumbling and falling. Stones rained down on them, a hail of detritus hitting whoever was underneath.

Kaya bumped into two young men who were helping each other up, stumbling forward in clouds of dust, getting hit again. A massive block missed Kaya by inches as she instinctively pressed back against the wall. Another rock struck her head. Blood streamed down her face.

Lhut appeared before her, taking her hand, urging her on. And then a pillar of wood and an avalanche of stone crashed down on Lhut, tearing his hand from hers. {{{

Kaya woke with a scream. Her breath was coming raggedly. Sweat covered her brow. She looked around in alarm, but all she saw was the shaft of moonlight falling in through her chamber window. All she heard was the racing beat of her own heart.

Kaya took a deep breath. She rubbed the scar on her brow. Her pulse began to slow down again. “It’s all right. I am here. It is over,” Kaya whispered.

Stiffly, she lay down on her mat again, staring out into the darkness.

It wasn’t true. Things were not all right. Nowhere near right! Kaya thumped her fist into the mat, muffling her cry with her pillow.

Then she drew the pillow away. Her eyes were gleaming. “It is not right. And: It is not over yet!”

Her next scream tore through the night with full force, a lament as much as an oath, a promise, an unbreakable pledge.

* * *

On the outskirts of town, the din of Varoonya’s bustling river port subsided into a soft background rustle until it finally faded into the gentle murmur of the waves.

Where the banks of the Roon turned green again, a festive little crowd had gathered on one of the meadows. People were idling about, glass in hand, a cloud of laughter, talk and music swaying over them. Strings of fairy lights answered warmly to the gold and lavender in a darkening sky. The air was soft, carrying scents of the coming summer.

Enim drifted happily between arriving guests and slaps on his shoulder, between farewell songs and conversations about his future. Slim and gangly as he was, he danced with more joy than grace, but his sweet smile and boyish charms still brought more than one kiss to his lips.

Enim had dressed for the occasion by putting on the least worn of his usual blue baggy pants, the loose folds drawn tight at his ankles. The short crimson vest over his shirt, however, was exactly the same as always because of the hundred tiny pockets full of potions and crystals and magical implements. Enim wasn’t going to go out without his equipment. So, wand tucked into his broad linen belt, Enim looked just his usual self. Which was precisely what everybody had come to celebrate anyway, right? Laughing, Enim pulled off his cap to push black hair from his brow when he suddenly froze.

A thousand tiny stars were gathering around him.

Enim looked about in confusion. But he found the source of magic soon enough.

Yoor had his arms stretched toward the sky, his skin shimmering in soft shades of blue and violet like the wings of a butterfly, subtle hues of color dancing over his velvety body.

Yoor brought his hand down in a circular motion. The stars multiplied into a shimmer of gold, arranging themselves into high pillars and arches, a sheer temple of light rising over Enim, the sacred hall filled with a celestial choir of triumph and glory.

Enim stared, wide-eyed. Then he laughed. “Oh, Yoor, please! Enough is enough!”

The music faded and the temple rained down in drops of amber to form a shiny pool at Enim’s feet, before even that dissolved into nothingness.

“Goodness me,” Enim gasped as he gave Yoor a hug. “I have only graduated from the academy. Not ascended to the heavens.”

“As good as,” Yoor murmured into his hair.

Torly threw herself at Enim from behind, squeezing him into a double hug before she stepped away to lean against Yoor’s shoulder.

Faces all around them had turned, eyebrows raised in surprise and delight, smiles beginning to spread. Butterfly people were rare, and Yoor’s appearance was admired as readily as the illusions he created. Noticing the eyes upon him, Yoor waved and gave a bow that was both humble meekness and extravagant flourish.

Torly laughed. “Yoor! You truly were born for the stage.”

“Thank you.” He straightened up, throwing pearly white hair back behind his neck. “I’ll be back on in two nights.”

Yoor tucked his arm under Enim’s. “But what about you? Where will you go now that you are leaving the academy behind?”

A crooked smile stole onto Enim’s lips. “As far away as I can, you might say. I’m going to the Mountains.”

“To the Mountains!” Yoor’s eyes widened. “Really? But why? There is nothing there! What do you think you’d do?”

“There is not nothing there, surely,” Enim frowned. “There is nowhere where there is nothing. There’s just places you haven’t thought about yet.” He wrapped his arms around his chest. “But to be quite honest, I don’t know what is there either. That’s why I am going. I have lived in Varoonya all my life. I’d like to see something new. To venture out into the unknown. Even if it is… challenging.”

“Oh my,” Yoor said, impressed. “What an adventurer. You could simply have sought work here. But, no. You go and travel the world. I am all amazement. I admit I had always thought you were rather tame. A stickler for rules, who always does everything right. How wrong I was!”

“Going to the Mountains is not against any rules,” Enim pointed out. “Otherwise, of course I would not do it.”

“Because you really do believe that rules are always right?”

Enim looked surprised. “Of course. What else? Rules are about what is right, and what is right is made a rule. That is the whole purpose of rules. If even the definition of right was not right, then where would we be and how would we know anything?”

Yoor tilted his head, giving Enim a sidelong glance. “I fear you may be in for a rude surprise, my friend.”

Torly pinched his arm. “Don’t be too sure, Yoor,” she winked. “Enim has his own way of looking at things and is not thrown off course so easily. His conviction is so strong that I would not be surprised if reality ended up bending to his will, and then right will truly be right, just like he said it would.”

“Now that’s what I call true magic,” Yoor said with feeling. “I wish they had taught us that at the academy.”

2

On the way to the Mountains, Toan was the last town still serviced by the stagecoach from Varoonya. From here, Enim had to make his own way.

He carefully chose a brown mare at the horse market and even met a farmer who agreed to take his baggage. So he set out, riding alongside the cart at a leisurely pace, taking in the landscape and the smell of fields on the breeze. Homesteads and hamlets glided past, sparkling streams and blooming orchards, ducks and cows and sheep. White clouds drifted overhead, and to Enim it all seemed a little like having journeyed into a picture book. Nice, but somewhat unreal. And impermanent too. Soon the picture book would close and then he would find himself back in the real world. In the Mountains, this time.

Whatever that might mean.

Enim shifted in the saddle.

He had grown up in Varoonya. All his family and friends were there. How would it be to arrive in a completely new world? To know absolutely no one?

Enim bit his lip.

There were diamonds in the valley of Shebbetin, he knew that much. And mines, where tons of stone needed to be moved with the help of magical traptions. Since he was an artificer, capable of creating and repairing traptions, surely someone would want to hire him? Even if everything he had done at the academy had been models and exercises. A real traption, sitting in the depths of a mountain like an old giant of cogwheels and magic, might still be another matter. Would Enim even be able to handle that, when he was all alone in the darkness underground?

Enim squared his shoulders and encouraged his horse to pick up the pace.

*

After two days, Enim reached Hebenir, a small village huddled into the steep rise leading up to the pass. All traders spent the night here. It was possible to reach Shebbetin in one day from Hebenir, but it had to be a very long day, especially if one was going with a cart.

So it was well before dawn when the merchant who had agreed to take Enim along let her wagon rumble out of the inn’s courtyard, lanterns swaying in the dark. Enim’s horse followed close behind. The dirt track they rode on wound up a slope behind the village, softly meandering through fields and meadows. But just as the first gleam of morning began to brighten up the sky, the road disappeared into a thick forest and they were plunged into darkness again. Only rare fingers of light penetrated the gloom here and there, slight shimmers breaking through the crowns in odd places, all giving Enim a vague, somewhat dreamlike feeling of his surroundings. Black trunks stood solemnly all around, companions to a wordless whispering song sent down from the treetops by the wind. The track got steeper and steeper, and increasingly thick undergrowth pressed onto the path from all sides, hindering their climb. Everything felt dark and dense.

And then, very suddenly, they were out.

As they rode up over the crest, sunlight exploded into Enim’s eyes, radiating brightly over the open highlands. The sky stretched endlessly overhead, a pale blue and gold striped with pink. A chilly wind blew hair into Enim’s face, and from high above came the shrill, piercing cry of a hawk.

Enim shook his head slightly, as if trying to wake up.

This was it, no doubt. He had arrived.

This was the Mountains.

They rode on the whole day, following the thin thread of a trail that wove across the highlands, a delicate dark yarn in a richly textured tapestry. Enim felt the slopes rise and fall beneath him like the timeless breath of the earth. He had become taciturn, like his guide. They just traveled on and on, in this vast, silent landscape, allowing themselves to become two tiny spots in a quiet, ancient, boundless world.

The sun moved along its arc. Gradually, the shadows grew longer until their dark fingers reached as far as the sky, pointing out into the universe. Enim had never before seen so many stars. In the blackness of night he heard the constellations sing to him with thin, ethereal voices, a nameless song of the cosmos that came to him from the depths of time and space. The trail could barely be seen any more in the meager gleam of their lantern. Enim was grateful when the moon rose, pale and impossibly big, over the ragged line of the mountains. They trotted on, bathed in the silvery silence that now covered rocks and meadows.

Suddenly, the cart came to a halt.

Enim startled. He reigned in, then rode up front to see what was the matter.

His gaze hardly found the outlines in the darkness of the valley.

It was only a few huts at first, huddling against the slope. But farther on, they condensed into a thick crowd of buildings, a black tangle, a confusing shadow full of nooks and edges in the ghostly moonlight. Over to one side of the valley, lights were visible, and shapes of stone houses with hearth fires shining through their windows. Enim let out a deep breath.

“Shebbetin,” his guide said in a hushed voice, as if she too felt she was standing at a portal between two worlds.

Enim gazed down at the jumbled town. He could not really see or understand it, in the middle of night and darkness. He knew that. But still. Here it was. He took another long look at the mysterious life stretching out and hidden before his eyes.

Gently, he pressed the flanks of his horse and rode down into the unknown.

* * *

Pale morning light fell into the inn’s chamber.

As Enim climbed down the stairs in search of breakfast, he found the tap room occupied by a bustling group talking animatedly—in Vanian. Enim blinked. The innkeeper was right in the middle. Waving, and joking loudly. In Vanian.

Enim realized that last night, his guide had been the one to do all the talking, walking out toward the stables with the innkeeper. Enim had never thought to listen for the words. What would it have been other than Kokish, the language everyone had adopted as their own since the Transition?

A gust of wind blew in as the door opened and the boisterous group jostled out, trampling and shouting, leaving palpable silence behind. Slowly, dust began to settle between slanting rays of light. The echoes of ages past, of a language relegated to history, lingered on.

Enim sent a silent prayer of thanks to his old-fashioned parents for still having spoken the abandoned language at home. He might stand a chance.

Enim cleared his throat.

“Good morning,” he tried in his best Vanian.

The innkeeper gave him a bright smile as she turned around to face him. “Good morning!”

Right. What next? Enim searched his childhood memories for some follow-up words, for the obvious question. “You talk Vanian?”

“Of course. Everyone in Shebbetin does.”

Enim stared at her, stunned.

Enim shook his head at himself, or at Shebbetin, or the world. Such an obvious thing! Yet no one had told him. He had not thought to ask either.

Everybody spoke Kokish these days, didn’t they?

No. They did not.

Or only a little. The innkeeper’s Kokish turned out to be even more halting and bumpy than Enim’s Vanian. However, the woman assured Enim while wiping her hands on the apron, the distinguished people, the mine owners and such, all spoke fluent Kokish. No worries there. It was just the ordinary folks who did not.

Enim rubbed the back of his head. The notion of splitting humanity into groups of distinguished and ordinary people simply slipped past his mind for the moment. But the old Vanian… that caught. Kokish was the language of his heart, and of his head too. It was the language in which he had become an artificer. The language in which dreams came to him at night. Would he not be able to speak it, now? Would Enim still be able to be himself, in this new home of his?

Enim sighed.

He might have to resign himself to a period of stuttering and speechlessness. And a time of intense learning. This certainly wasn’t going to make his new start any easier.

Well. He would manage. His Vanian was rusty, but strong and healthy underneath. Or so Enim hoped.

The innkeeper was making breakfast.

Enim watched in silence.

Then another thought occurred to Enim. A happy one! Which was what he needed right now, anyway. There might be a welcome gift waiting for him, since a few friends unable to make it to his farewell party had promised to write to him instead. Maybe their letters had already arrived?

A smile came to Enim’s lips.

He had another go at Vanian. “Please, where… ah… have letters? Pouch! Pouch collection!” The words came back to Enim just in time.

“The nearest pouch collection point is in Behrlem.”

“Behrlem…” Enim hesitated. “Where, please?”

The woman briefly raised her eyes to him while ladling beans onto a plate. “Behrlem is a town south of Hebenir, a ride of two or three hours.”

Enim looked back at her, perplexed. “But…” Enim switched back to Kokish. “What I mean is the local pouch collection point for Shebbetin. You know, where the county courier drops off the pouch, and where local people can go and collect their letters?” And then he said it all again in Vanian, as best as he could.

“In Behrlem,” the innkeeper repeated, arranging potatoes.

“But… I cannot three day travel for get my letters!” Enim’s voice held all his bewilderment and confusion.

The woman took pity on him. “Well. For you, there might be a way. Do you know any of the mine owners? They have their own pouch collection. A private courier, who rides to Behrlem once a week. If you ask nicely, they might let you join. You, being an artificer and all, bearing the seal of the academy.”

Enim still looked perplexed. “But… in Shebbetin thousands of people live. How they get letters?”

“They don’t,” the innkeeper said dryly. “Except if they are lucky and some trader takes the pouch along.”

Enim stared at her, aghast. “But that… not possible. People in Shebbetin so far away. And then no letters? No.” Enim shook his head. “This not right. Not possible. There is rules for this. The county bring pouch to everyone. Everyone. It must be.”

The innkeeper turned away to pour steaming water into a teapot.

Enim appealed to her. “Of course, tell county. Bureaus, in Varoonya. Of course they make this right, very soon. They make pouch collection point in Shebbetin. And letters good everyone.” Enim pinned the woman with an imploring gaze.

“Look here,” she said somewhat defensively. “This is an inn, and I am the innkeeper. I have given you all I have on the subject.”

“But—“

“Here’s your breakfast,” she said firmly, but not unkindly, pushing the tray over the counter. “I’ll be around the back if you need me.”

*

The only other guests still at the inn were huddled in the far corner.

“Did you hear that?” Kaya asked in a low voice.

“I most certainly did.” Lhut leaned forward slightly. “He is unusual, this fellow.” Lhut let his gaze wander over Enim, who had his back turned, eating breakfast with unseeing eyes. “He is from Varoonya, yet able to speak Vanian. And not too proud to do so, even though he has to scrape and scramble. He could have pushed all the awkwardness and headache on to the innkeeper by switching the conversation to Kokish. But he did not. He kept on making the effort himself. Not even afraid of sounding strange. That looks like someone with a strong and friendly mind.” He nodded respectfully.

Kaya’s eyes narrowed. “He saw a problem, and got upset. He did not opt out with his purely personal solution, even though he could have. He did not instantly forget about all the other people. Instead, he thought about what should be done.”

Lhut nudged Kaya’s elbow. “Go on. Right now, he does not have a clue. Let’s make sure we get to him before anyone else does.”

*

“Excuse me.”

Enim snapped out of his absorption.

A lean but strong-looking woman stood beside his table, with black skin and dark hair that was both very short and very curly. A long scar ran across her brow down to her ear.

“Yes?” Enim said tentatively. But in Vanian, like her.

“My name is Kaya.” She nodded over at the table in the far corner, where a muscular man with friendly eyes and a head full of brown curls was smiling back at them. “Would you join me and my friend Lhut for breakfast?”

Enim was happy to agree. What could be better for him than making a few acquaintances and getting first-hand introductions to Shebbetin?

“I know you are new to the Vanian language,” Kaya said. “I will speak slowly, in short sentences. And if I forget, please give me sign.” She raised one shoulder apologetically. “I easily get carried away by my own speeches.” She winked at him.

Enim tilted his head. “I can talk only hard. But understand is better. It is all right. You can speak like normal. So I learn.” He smiled bravely. “And if not, I say and show.” He waved merrily at her.

Indeed, it turned out Enim was able to follow Kaya’s conversation, even if it took a considerable effort. And that was due to the language, but also the content, which caused Enim to ask for an explanation yet again. “What is a warmling?”

Kaya smiled. “It’s what we call them around here. They are just round stones, really. Warm stones, which people put under their blankets in winter. I run an oven at the edge of town where I heat them up, then go through the lanes with a pedalcart to sell them. It’s a small business, like the kitchens or the market stalls.”

Enim gratefully remembered finding a heated bed in his unheated room at the inn last night. He nodded.

“And before that, we were both working in a mine,” Lhut put in.

“Oh, really!” Enim felt familiar territory come within his reach. “But that wonderful! Can you show me, maybe? I will very much like to see a mine, with people who really know! Because I want to go work in mines also, with traptions.”

Lhut and Kaya exchanged a glance. “Yes. We would love to show you a mine and tell you what we think of it. There’s nothing we’d like better. Just give us a bit of time. We need to make arrangements first.”

Enim nodded.

He took a sip of tea as another question came to his mind. “Why you not work in the mine any more? Because of the mine? Or because of work you do now?”

“Because of the mine.” Lhut folded his hands on the table in a slow, deliberate motion. “Very much because of the mine. You see, there was an accident in that mine, three years ago, and I got injured.”

“Oh?” Enim set down his mug. “I am sorry. And I am glad you have heal so well.”

Lhut paused. “Now,” he said. “My legs have not healed all that well, actually.”

“Really?” Enim asked sympathetically, leaning sideways a little to squint under the table. “You still pain—“ He stopped. He had seen the two stumps that were all that was left of Lhut’s thighs.

3

Enim was lying on his bed at mid-morning, staring at the ceiling. Lhut and Kaya had gone back to their daily work, leaving with a promise to give him a tour of Shebbetin later on. Enim had meant to go out and make contact with at least one of the mines in the meantime, but he felt disturbed and unfit for pleasant introductions. He could not present himself now, neither as a likable person nor as a competent artificer.

Enim tossed on his bed.

‘What’s more,’ Enim thought, ‘why was Lhut still sitting around with the stumps of his legs like that? I know people often need to wait for a wound to heal before an aid can be placed. But surely not three years?’ Enim turned around. ‘I’ll ask him next time we meet.’

And as if this was the answer to all his doubts, he fell asleep.

* * *

“Welcome to the Mansion! The heart of Shebbetin!”

Kaya spread her arms wide in a triumphant gesture. She half-turned, grinning back at Enim over her shoulder.

Enim recognized that dense, crowded area full of nooks and edges that he had noticed on his arrival, looking down from the hill into darkness and moonlit tangles. By day the quarter still seemed crammed, tousled and unwieldy, and only slightly less mysterious.

“It is just a mass of houses grown together, really,” Kaya explained. “People moving into town squeezed in another cabin where they could, or an extra room at least. In the end they simply covered up the space left in between with another roof. So alleys turned into corridors, and the open places of a village into the halls of a great house. Our Mansion.”

Kaya let her fingers trail along the rough stone wall beside her. “I’ve always loved it. For being a good neighborhood, with people ready to help each other out in all the hardships they face. A friendly, a trustworthy place.”

Kaya hesitated. “As far as the people are concerned,” she added grimly. “The houses, charming as they may be, actually are a death trap. And everyone knows it. Bring a spark to the Mansion and you have killed everybody inside. The thatched roofs will go up in flames like tinder, in a labyrinth of stone walls that keep anyone from escaping. That is why no one is allowed to bring fire near the Mansion, or to use it inside.”

Kaya tapped her hand against the low eaves of a hut, slapping the straw. “Very good for my business,” she added with biting sarcasm. “No one here has a hearth at home. Lots of demand for warmlings from outside.”

Enim bent low to follow Kaya through a small archway, then almost bumped into her as she stopped inside a courtyard lined with potted plants. Brambles climbed up the walls, and flowering vegetables graced the edges. With various traces of play and craft sitting in every corner, the even sand plane looked like a cross between a farmer’s garden and a charming village square.

“That’s the Snuggery.” Kaya was already kicking off her shoes before the door on the left. “Let’s pop in so you can get an idea of what Lhut is doing.”

The room was teeming with life. A floor full of rugs, blankets and woven grass mats held a jumble of kids big and small. Chalk drawings and writing squeezed into every corner of the boards along the walls. A few low tables were scattered across the room, most of them occupied by children deeply immersed in games Enim did not recognize, in sketching and building and watching with furrowed brows. Lhut was sitting over in one corner, surrounded by three kids with shiny eyes who were pulling at his sleeves while telling him something important.

Kaya’s voice flowed on across the buzz of the room. “This is Cahuan. She has founded the Snuggery.”

Enim turned. And froze. Cahuan was a butterfly, like Yoor. Enim stared. He had not seen this coming and was caught utterly unprepared. Cahuan seemed unearthly, fay. Her skin was velvety, shimmering in hues of green and gold. Under long dark lashes, her eyes looked out at him like deep green ponds, drawing him in, to drown perhaps, or to swim with the sunlight playing in the water in golden streaks. Like underwater plants, her long wavy hair was flowing down her back, swaying softly, and even in its rich green darkness there seemed to be little sparks shining through, like tiny golden fish darting through the seaweed, or brilliant reflections of sunsparks. Cahuan was round and full, and all of her body had a soft, unhurried grace to it that again reminded Enim of an underwater dance. ‘Perhaps she is a mermaid,’ he thought stupidly. ‘A butterfly mermaid.’

Enim pulled himself together. He did not know how long he had been staring, or how obviously. He blushed and narrowly stopped himself from giving a little cough. But everyone else did not seem to be staring back at him. So perhaps it had not been so bad.

Enim regained some of his composure. He was able to take in more of the Snuggery again, and of the conversation going on around him.

“He speaks Kokish, mostly,” Kaya was saying.

“Oh great!” A twelve-year-old girl with braids full of pearls and feathers beamed at Enim. The immense confusion of colorful patches that was her tunic swished and swayed before Enim’s eyes with flaps and frills and ribbons. “Will you come and talk to us? And read out stories? We have this one book, you know? Pulan…” She waved a brightly patterned arm through the air. The girl next to her, with broad cheeks and extremely short hair, whistled through her teeth and darted off.

Enim, meanwhile, received further explanations. “We always copy the words written in it, but we never quite know how to pronounce them. But now you are here!”

Pulan came back with a triumphant whistle and stomped to a halt before Enim. She proudly propped open the book, holding it directly in front of his nose. Enim felt expectant eyes bore into him.

“Ah…” He stared at the pages, blinking. Letters blurred, too close to his face. “Ah. Yes. I can read Kokish.”

The colorful girl threw herself at Enim for a brief but breath-taking hug.

“Brilliant!!” Then she added, “I’m Som.”

*

As Kaya and Enim left the Mansion behind, space between buildings reappeared and rapidly grew larger, until the last of the houses were only a scattering across the wide hillside.

“We cannot go into the mine just yet,” Kaya said as they climbed. “But you can walk past and cast a glance at the entrance, see some of the miners working there. It’s at least a bit of an impression.”

“Yes, very good.” Enim did not mind. To him, everything was new and worthy of exploration.

He could already see the two small buildings that flanked the entrance. They looked nothing unusual, Enim thought. Just the same kind of low stone house and thatched roof that he had seen so often in Shebbetin. Some people were gathered outside, joined by a few more coming out of the mine.

Then a shock rocked through the whole group. Enim heard a high, shrill cry coming from the depth of the mountain. Kaya’s hand clamped down on his arm.

“Nightling,” she breathed. “Run!”

Kaya started off. “Don’t look back!” she shouted over her shoulder.

Enim looked back instantly, unable to stop himself. But all he saw was people fleeing in all directions.

Enim turned and made after Kaya as fast as he could. He ran across the uneven meadow, stumbling, catching himself, hurrying on. Kaya was far ahead. The high grass brushed against his knees, threatening to entangle him.

Enim heard movement behind him. Something big was following, going very fast. Coming closer.

This time, Enim did not look back.

He kept on running. He felt more than saw a shadow behind him, to his left, and veered to the right, down the hill. And fell. Stumbling over a root, Enim dove headlong down the decline, crashing down hard. He rolled and tumbled on with the force of the impact, plunging downward without orientation, without control.

Finally, the avalanche came to a halt. Fingers clutching frantically at the grass, Enim managed to keep the world still.

He whipped his head around.

But the shadow was not upon him.

It had moved on alone up above.

Enim could see the nightling clearly now. Up on the hillside she was racing through the grass like the wind, fast, smooth, unbroken, in long, elegant bounces. Her black coat gleamed in the sunlight, showing the perfect play of muscles as her long slim body dashed on with the intense energy of a wildcat. The nightling was huge, much larger than a human, but seemed light, unbounded, almost weightless. She raised her head and gave one more sharp, eerie cry. Enim’s hair rose on his neck. The piercing scream seemed to have penetrated the very marrow of his bones.

Then the nightling took wing.

Enim’s eyes grew wide.

With one last bounce, the nightling had thrown herself into the steep fall of the hill, into the rise of the wind. She spread her wings, two sails made of darkness, of shiny black leather, perfect half-circles the color of a new moon. The air bore the huge creature effortlessly. The nightling rode on the breeze, turning into a sudden gust, rising up high with its thrust. She cut through the sky, swift and elegant as a swallow, circle upon circle, a black beauty unrestrained by the pull of the earth.

But she returned.

In a long, low dive, the sinuous creature swept over the grassland just above the tips of the blades, her open mouth a huge gaping hole, as wide as her whole body. With breathtaking speed she advanced toward Enim. And rushed past.

Enim lay on his back, pressed into the ground. His breathing had stopped. The black shadow rose up again, higher and higher, challenging the wind, soaring like a streak of dark lightening tearing up into the sky.

But this time, she did not come back. She let herself be carried away, a slim gracious outline, a flight of perfect wings circling away in fast, seamless swings, in a long, drawn-out flourish. Enim’s gaze followed her dance until she disappeared into the light over the mountains.

Enim closed his eyes. He felt the solid earth underneath his body. He took a breath. And another. His heart was trying to come back to a normal rhythm. Enim laid a hand on his chest to help.

When he opened his eyes again, Kaya was beside him.

“Are you all right?”

Enim nodded.

Kaya stared at him hard, a skeptical look in her eyes. Then she shook her head. “You are in shock. You have no idea if you are hurt.”

With an authoritative gesture she pushed Enim back onto the meadow when he made a move to get up. But her touch was incredibly gentle as she took hold of his hand and moved the fragile joints one by one, so careful as if she was handling a treasure made of blown glass.

A deep sigh rose up from Enim’s chest. He felt lightheaded. Willingly, he succumbed to Kaya’s ministrations, bent his elbow, raised his arm, lifted his shoulder. He took off his shoes, his trousers, his shirt.

Kaya’s focused attention drew him in, let him become aware of every single toe he had, every bone in his spine. He knew once again he had a liver, a kidney, a soft belly full of vital organs. And a heart that had returned back to its natural rhythm.

“Congratulations! You have survived.” Kaya grinned. “Scratches and bruises,” she added with a dismissive wave of her hand.

Enim took a deep breath. “Thank you.” He felt a little more like himself again. He began to grope for his trousers in the heap of discarded clothes.

“That was a good move, to roll down the hill like that.” Kaya sounded impressed.

Enim snorted. “Thank my body. Or the ground.” His fingers imitated a very uneven surface. “I sure not this had planned.” He ran a hand through his hair. “But, tell me. Why we run? Is it not that if you run away, hunters start to chase?”

“Yes. They do. If they are hunters. But the nightlings are not. Or, at least,” Kaya amended, “they do not chase anything nearly as big as you and me. They eat insects, such like.”

“Oh.” Enim’s head had not quite arrived back in its usual place yet. He shook it very cautiously. “Right. But, then also, why we run? If they are not dangerous. Not hunting us.”

“They are dangerous. Very dangerous. If caught in a tight spot. Nightlings go into caves to sleep, and if they get surprised in there, they panic.” Kaya looked back toward the entrance of the mine. “This here may have been bad.” She hugged her knees.

Then she pushed herself up in one fierce move, holding out a hand to Enim. “Come.”

*

Moans and cries filled the air. The injured were staggering out of the mine, leaning heavily on the arms of their fellows, their eyes wild with pain. Groans and stifled oaths escaped from their lips. Sobbing uncontrollably, a large, hulky man was hunched down on the ground, holding the lifeless body of his son in his arms. Three people were kneeling beside him, sending a grievous lament up into the wind, a keening, a prayer.

With impatient urgency, a tightly knit group pushed past, piercing screams coming from their midst, a trail of dark red stains left behind in their wake. The woman they laid down on the meadow was young and sturdy. But her right leg was in shreds. Blood gushed out over the hand of the miner who tried to squeeze her artery shut. As he leaned onto her with his full weight, her whimpers rose into another wail, then broke off suddenly. Her head lolled to one side.

“Fainted,” the girl beside her said, in a thin voice. She ripped a piece of cloth off her shirt and deftly tied it around the leg, twisting the bandage tight with a stick. “She’ll survive,” the girl said defiantly. “We’ll only have to get the leg taken off.”

4

In one corner of the Snuggery, the elder was singing drawn-out elegies of the mountains, full of longing, full of mourning. Som was crying in his lap, a sad lake of colors over softly shaking shoulders.

All around Lhut, stripes of torn fabric lay scattered on the ground. Two of the children were still with him, practicing how to tie and tighten and loosen bandages. Most had had enough, and one was still busy rolling the cloth back up. Lasa and Lunin, the twins, had gone straight into impersonating nightlings and fleeing people in the courtyard, where a lot of disturbing emotions got translated into screaming and hiding, running and ducking. But in addition to a great deal of exercise and acting, there now also were discussions about the scenario. And the actual behavior of nightlings, a subject on which the two seven-year-olds sought confirmation from Cahuan from time to time.

At the moment, the nightling was clawing her way through an ineffective barrier that had been put up before a mine entrance to keep out dangerous visitors.

“Yes. It is very hard to make barriers that cannot be broken by beings who dig their way through stone,” Cahuan agreed. “Almost impossible, I should think. But it may not be necessary. In fact, some mines have very light wooden barriers over all entrances, including air shafts and all. And people doing rounds before each shift, to check. If they see any broken barriers, they will raise the alarm and tell the miners to keep out.”

Lasa stopped clawing and turned around, a question in her dark brown eyes. “But then what happens? They never go into that mine again?”

“Oh, they do. But first, they send in noisy traptions at one entrance, and watch the nightling flee out the other end. After that, people go in to work. And also repair the broken barrier.”

Lasa and Lunin nodded and instantly began setting up a mine with multiple entrances and wooden grids.

“But then why did people be surprised by nightling in the mine today? If they should have known warning?” Enim inquired.

“Because,” Kaya said through clenched teeth, “this mine has no barriers, and no system. Because Naydeer cannot be bothered to maintain one.”

Enim watched her, slightly intimidated by her expression. “Naydeer is owner of mine?” he ventured cautiously.

“Yes, she is. And it was in one of her mines that Lhut and I have been working. It was her mine that collapsed on us too.” Kaya’s eyes narrowed. “And not by chance either.”

Enim’s brow furrowed. “How you mean, not by chance?”

“I mean,” Kaya said in a cutting voice, “that a ton of stone rained down on people who were ready to challenge Naydeer. In exactly that moment, on exactly their heads.”

Lhut came over to join them. “There have been lots of accidents in Naydeer’s mines. She has been saving on timber that supports the tunnels, and on adits that bring in fresh air. And the cost of that was the life and limb of miners.”

Lhut sat down, his short legs stretched out before him. “We were going to force her to do at least the minimum: air, and tunnels that don’t cave in. At least that. We were ready to stop the mine until she had done it.”

Fists clenched, Kaya was looking out into the past, her eyes unfocused. “Naydeer must have found out what we were planning. She certainly knew we were pushing for our safety, because at first we had tried to talk to her about it. Naive fools that we were!” Kaya laughed scornfully. “Naydeer just gave us a kick in the guts. And threatened some more. But we did not give up. Too many lives had been lost in those mines. People were ready, were angry enough, to not take it anymore. So we rallied—and the moment we did, her mine collapsed on us. By pure coincidence.”

Enim clutched his arms, so hard it hurt. “But, please, you not say that Naydeer has make fall down the mine, on purpose? On people? She cannot do that. That murder!”

Kaya looked at him, her eyes cold as steel.

*

Enim ate his lunch in a corner of the Snuggery courtyard, his gaze turned inward. His head felt empty, and Kaya’s words echoed inside, a hollow, ghostly sound that could not find a home.

Enim sighed and decided to postpone to later what he could not deal with right now. Holding on to the soothing warmth of lentils and potatoes in his stomach, to the savory taste of fresh herbs on his tongue, Enim gratefully let the wisdom of his body take over for a while, calming and steadying. He leaned back against the wall, feeling the solidity of stone against his shoulders, the gentle touch of sun on his face.

Enim’s gaze drifted over to the three kids in charge of serving lunch today, who were deftly handling things with an air of confidence and routine. Two younger girls who had been roaming out in the Mansion for too long came running in, hoping to still grab a portion. Kaya, Lhut and Cahuan were sitting on the little staircase by the side wall.

Enim pushed himself up and joined them.

“So have you spoken to any of the owners yet?” Cahuan shuffled to make room for Enim. “I hear you want to work for them, as an artificer?”

“Yes, I want.” Enim said hesitantly. “I wanted.” His fingers tapped a little pattern onto the rim of his plate. “I want. But, no. I have not spoken. I not sure how to start.”

“Go to Manaam,” Cahuan instantly suggested, a bright smile rising in her face. “He is the best one by far.”

“He is your friend?”

Cahuan nodded, the happy glow still on her face. “Yes. He is. I do not see him often, but we are quite close.”

Kaya put her spoon down a little too hard on her plate. “Manaam is paying for most of the Snuggery. So that is how we keep Lhut and Cahuan and everyone here fed. Also, in Manaam’s mines, tunnels don’t fall onto people’s heads. He’s as good as it gets, around here.” Kaya set down her plate on the steps behind her, as if that might be needed to keep it out of harm’s way.

“Manaam also runs a healing bag for his miners,” Lhut joined in. “Along the same principles that Kaya has come up with when she started the first healing bag in Shebbetin, in our mine.”

“What is healing bag?” Enim asked, inevitably.

“It’s a way for people to help each other out in the case of injury or illness,” Lhut explained. “A large group of people each drop a small amount of coin into the bag. And then, when someone gets seriously ill or has an accident, as I did, coin can be taken from the bag to go to a healer.”

Enim blinked. “Everybody go to a healer. Everybody who sick, who needs. No bag necessary for this.”

Silence descended on their little group.

Enim looked at Lhut, and at the stumps of his thighs. A lump was beginning to form in Enim’s throat. “Not here?” he whispered.

“No. Not here,” Lhut replied in a low voice, brushing a hand over the rim of his thigh. “We did pay a healer to take off my mangled limbs. So I did not die. But that was it. We have nothing more. And for many, not even that.”

Enim turned away. “No.” It was a mere breath. An objection to the world, addressed to the wind. “No. That not possible.”

5

The afternoon sun shone down gently on the broad, tree-lined avenue as Enim marveled at beautiful mansions, quite different in style from the quarters around the inn. This was almost like a little town unto itself, somewhat removed from the main settlement, cultivating its own style and atmosphere.

Enim found Manaam’s house easily.

A middle-aged woman opened the door and led him into a parlor full of polished wood and delicately painted paper screens. She would go and see if Manaam was available.

Enim nervously paced across the room, his fists clenching and unclenching.

Then the double doors opened. Manaam came strolling in with leisurely elegance, his flowing silk robe cut low to reveal the graceful line of his collarbones. He offered his welcome to Enim in a resonant, genial voice. And in Kokish. A wave of relief washed over Enim. He liked Manaam instantly.

And Manaam seemed just as pleased as their conversation carried on. “Having someone of your skill level in Shebbetin is a blessing,” he praised. “You won’t believe how I had to chase after artificers in the lowlands a few years ago, just to get a proper locomotion traption for my mine. None of the artificers wanted to come up here. Finally, I found one who constructed it down in Behrlem, leaving it up to me to get it back here in one piece and install it inside the mine. Which has stretched local competence to the limit, I can tell you.”

Manaam opened an ornate wooden chest by the wall and thoughtfully peered in. “Ah! Here.” He fished out a large, rolled-up parchment. “This is the glorious deed. Or at least the theory of it.” He unfurled it on the table. “I confess I have no idea what any of these mean.” Manaam vaguely waved a hand over myriad fine lines, interspersed with small pentagrams and tiny scribblings. “But I suppose you do?”

Enim licked his lips. He stepped up close and began perusing the scroll with furrowed brows. With a soft touch, his fingertip followed the slings and crosses among the lines, ventured deep into the labyrinth, trying to find its heart.

The silence stretched.

Then Enim looked up.

A secret smile crept into his eyes.

“I do.”

Manaam took Enim to see the real thing right away.

The mine was well lit where they stood, with magical lanterns set up all around the traption.

“I have someone who can do routine things like this,” Manaam related. “Changing the vim stone. But since you are here anyway for your introductory tour, I guess I might just as well employ your services.” He chuckled slightly. “You will have other things coming your way, I warn you. Some of the owners here are less concerned with having the most advanced traptions, and only when their old ones grind to an actual halt do they call someone in to check.” Manaam laid a hand on Enim’s shoulder. “You will find a lot of interesting work here. Things you have never seen before. Traptions older than yourself,” Manaam finished with a grin.

Enim’s brows shot up. He was not sure whether to take that as a joke. Traptions had changed so rapidly in the last few years that one almost three decades old— “Here you go,” Manaam interrupted his thoughts.

He had already taken the lid off the traption’s case.

The lower half of the huge brass globe was filled with a cobweb of spun glass, holding glinting crystals in its midst. Enim crouched down, trying to find the pattern from the scroll in this delicate labyrinth. And he did. At least vaguely. Enim could not remember exactly which spell was embedded in which crystal. Except that if the pattern started there at the back…

Lost in his contemplation, Enim realized only belatedly that Manaam was holding out a hand for him, with a perfectly cut amethyst lying in his palm.

“Right.” Enim took the crystal, rolling it gingerly between his fingers. He wanted to get a better grasp of things before he actually intervened. He straightened up, his eyes darting from the cloud of glassy threads to the huge cogwheels on the wall, and the chain descending down into the depth of a tunnel. Wagons full of debris patiently sat on their rails, holding on to the chain, waiting to be moved.

“So this is where the power goes,” Enim murmured.

“Ah. Yes.” Manaam had nothing much to add to the obvious.

Miners were peeking around the corner, checking if things were going to get moving again soon.

“Right.” Not so hard. It was only to replace a vim stone. You usually did not even need a full-fledged artificer for that.

Enim cleared his throat.

He pulled his wand from his belt. At the heart of the invisible web, an amethyst identical to the one in his hand gave off a dull gleam. Enim’s eyes narrowed as he pointed straight at it. He spoke just one word.

Noiselessly, the crystal floated out and landed softly in Enim’s bag. At the same time, Enim sent the stone in his palm into the air, with one more flick of his wrist. And in one fluid motion, without ever disturbing the intricate pattern of gossamer threads, the amethyst settled into place, as softly and delicately as a snowflake. Enim held his breath, as if to preserve the silence and the fragile tenderness of the cobweb.

But suddenly all hell broke lose.

Rattling and clanking, the cogwheels above his head began to move, the chain sending echoing groans down the tunnel. Miners shouted and waved at their comrades.

Enim shot around. His eyes darted from the rumbling chains to the sparks flaring in the crystals. But a hand came down on his shoulder to pull him away.

“You’ll have time enough to study these later,” Manaam shouted over the din. It was he who had set the traption in motion. Since the vim stone had obviously been replaced, Manaam had deemed it best to let work continue immediately.

Enim exhaled deeply.

Glancing back at turning cogwheels and massive stone, he allowed himself to be led away.

They climbed up the innards of the mountain until they reached its gaping mouth and crawled out into the open. Enim raised his arms to the sky. Fresh, clear mountain air once again filled his lungs. Enim felt the wind in his hair and watched the sun sneak in pale rays between the passing clouds.

“Very well!” Manaam pocketed the old vim stone that needed refilling. “I think I should give a dinner party in your honor, Enim. That way you will meet some of the other owners and can offer your services to them too. I am sure you will be welcome.”

Enim nodded. A smile was beginning to spread across his face. Maybe starting his new life was not that difficult after all!

He whistled at a passing bird.

Perhaps some of these other matters that had disturbed and confused him could be sorted out now as well? Such as the pouch collection point. That, at the very least, must be easy to settle straight away, right?

Enim said as much as they were looking out over Shebbetin.

Manaam gave him a weird sidelong glance. He cleared his throat. “You can write to Varoonya, of course. But I don’t think very much will happen. And certainly not quickly.”

“Well.” Enim’s brow creased. “If it takes long, we should start soon.” He tapped a finger against his thigh. “Perhaps in the meantime, the existing weekly courier to Behrlem could bring everybody’s pouch, rather than just the owners’? Surely that could be done, even if she might have to lead some extra horses?”

Manaam’s face took on a surprised look, then seemed to waver between anger and laughter. The laughter won out, but Enim still sensed a little sting behind it.

“Quite the revolutionary, aren’t you?” Manaam assessed Enim with narrowed eyes. “Look here,” he finally said, an edge to his voice. “You can suggest all manner of rash action to me. I don’t object. I even wish to hear. Feel free to speak your mind in my presence. But, please, don’t do it over dinner. I do not wish to get accused by the other owners of having introduced a troublemaker into our quiet little society. Do not rock the boat before even getting in. Don’t reallocate the owners’ resources before even becoming a member. You do not understand the forces at work here. Be cautious.”

6

It was quite a steep slope already, but still human hands had squeezed amaranth and rye onto narrow terraces and dug a hundred names for potato into the meager ground. A llama gave Enim a curious glance from behind a wall.

Enim had gone up the hillside by himself, to the edge of town where he had seen fields and gardens grow out into the meadows. Farther out, he could see a flock of sheep moving up into the highlands, and decided to go back down that way, so he would reach Shebbetin from a side he had not been to before.

He walked along the long, slow curve and soon enough the open meadow was dotted with sheds again, in between shaggy long-horned cows. In passing, Enim peered into one of the barns through an open door and saw people sitting on the ground. It seemed odd, somehow incongruous. But Enim gave it no further thought and just moved on, following the narrow dirt track that appeared beneath his feet as houses began to close in around him.

Their walls were made of rough field stones, but less well built, less carefully crafted than in the Mansion. Indeed, they looked crooked and ragged, unstable and uncared for. He came across some crumbling walls, of cabins that had never been finished or perhaps fallen to ruin already. Piles of rubble lay about, partly overgrown with weeds, the hiding place of a sickly dog that fled with a whine as Enim approached. Three toddlers slouched in the dirt outside a house, staring at Enim with empty eyes.