7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

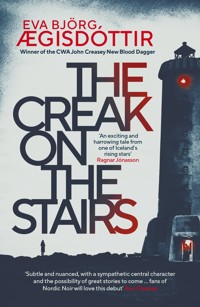

When a woman's body is discovered at a lighthouse in the Icelandic town of Akranes, investigators discover shocking secrets in her past. First in the disturbing, chillingly atmospheric, addictive new Forbidden Iceland series. **WINNER of the CWA New Blood Dagger** **WINNER OF THE CWA JOHN CREASEY NEW BLOOD DAGGER** **WINNER of the Storytel Award for Best Crime Novel 2020** **WINNER of the Blackbird Award for Best Icelandic Crime Novel** **SHORTLISTED for the Amazon Publishing Readers Award for Best Independent Voice** **SHORTLISTED for the Amazon Publishing Readers Award for Best Debut Novel** 'Eva Björg Ægisdóttir's accomplished first novel is not only a full-fat mystery, but also a chilling demonstration of how monsters are made' The Times 'Fans of Nordic Noir will love this moving debut from Icelander Eva Björg Ægisdóttir's. It's subtle, nuanced, with a sympathetic central character and the possibilities of great stories to come' Ann Cleeves 'An exciting and harrowing tale from one of Iceland's rising stars' Ragnar Jónasson _________________ When a body of a woman is discovered at a lighthouse in the Icelandic town of Akranes, it soon becomes clear that she's no stranger to the area. Chief Investigating Officer Elma, who has returned to Akranes following a failed relationship, and her collegues Sævar and Hörður, commence an uneasy investigation, which uncovers a shocking secret in the dead woman's past that continues to reverberate in the present day … But as Elma and her team make a series of discoveries, they bring to light a host of long-hidden crimes that shake the entire community. Sifting through the rubble of the townspeople's shattered memories, they have to dodge increasingly serious threats, and find justice … before it's too late. For fans of Yrsa Sigurdardottir, Ruth Rendell, P D James, Sarah Hilary and Camilla Lackberg _________________ 'Elma leaves Reykjavik CID for a job with the police in her hometown of Akranes, deeming it "every bit as quiet as it appeared to be" — until the discovery of a murdered woman starts to unravel a thread of long-buried crimes hidden deep in the community. Elma is a fantastic heroine' Sunday Times 'We're used to Icelandic writers lowering the temperature — in more ways than one — and Ægisdóttir proves to be adept at this chilly art as any of her confrères (and consoeurs). Elma is a memorably complex character, and Victoria Cribb's translation is (as usual) non-pareil' Financial Times 'A deserted lighthouse and a murdered woman set the scene for this haunting and compelling mystery where the dark secrets of a small town are shockingly exposed. As chilling and atmospheric as an Icelandic winter' Lisa Gray, author of Thin Air 'The setting in Iceland is fascinating, the descriptions creating a vivid picture of the reality of living in a small town. The Creak on the Stairs is a captivating tale with plenty of tension and a plot to really get your teeth into' LoveReading 'At each stage, Ægisdóttir is not giving us information but asking things of us. She's getting us to think through the implications: what if it's him, what if it's her, what would it mean? We're involved, we've got skin in the game and we can't ask for more as readers' Café Thinking

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 498

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

iii

THE CREAK ON THE STAIRS

Eva Björg Ægisdóttir Translated by Victoria Cribb

CONTENTS

ICELAND

PRONUNCIATION GUIDE

Icelandic has a couple of letters that don’t exist in other European languages and which are not always easy to replicate. The letter ð is generally replaced with a d in English, but we have decided to use the Icelandic letter to remain closer to the original names. Its sound is closest to the voiced th in English, as found in then and bathe.

The Icelandic letter þ is reproduced as th, as in Thorgeir, and is equivalent to an unvoiced th in English, as in thing or thump.

The letter r is generally rolled hard with the tongue against the roof of the mouth.

In pronouncing Icelandic personal and place names, the emphasis is always placed on the first syllable.

Names like Elma, Begga and Hendrik, which are pronounced more or less as they would be in English, are not included on the list.

Aðalheiður – AATH-al-HAYTH-oor

Akranes – AA-kra-ness

Aldís – AAL-deess

Andrés – AND-ryess

Arnar Arnarsson – ARD-naar ARD-naarsson

Arnar Helgi Árnason – ARD-naar HEL-kee OWRD-nasson

Ása – OW-ssa

Ásdís Sigurðardóttir (Dísa) – OWS-deess SIK-oorthar-DOEH-teer (DEE-ssa)

Bergþóra – BERG-thoera

Bjarni – BJAARD-nee

Björg – BYURRG

Dagný – DAAK-nee

Davíð – DAA-veeth

Eiríkur – AY-reek-oorviii

Elísabet Hölludóttir – ELL-eessa-bet HURT-loo-DOEH-teer

Ernir – ERD-neer

Fjalar – FYAAL-aar

Gígja – GYEE-ya

Gréta – GRYET-a

Grétar – GRYET-aar

Guðlaug – GVOOTH-loig

Guðrún – GVOOTH-roon

Halla Snæbjörnsdóttir – HAT-la SNYE-byurs-DOEH-teer

Hrafn (Krummi) – HRAPN (KROOM-mi)

Hvalfjörður – KVAAL-fyurth-oor

Hörður – HURTH-thoor

Ingibjörn Grétarsson – ING-ibjurdn GRYET-arsson

Jón – YOEN

Jökull – YUR-kootl

Kári – COW-rree

Magnea Arngrímsdóttir – MAG-naya ARD-greems-DOEH-teer

Nói – NOE-ee

Rúnar – ROO-naar

Sara – SAA-ra

Silja – SILL-ya

Skagi – SKAA-yee

Sólveig – SOEL-vayg

Sævar – SYE-vaar

Tómas – TOE-maas

Viðar – VITH-aar

Þórný – THOERD-nee

She hears him long before she sees him. Hears the creaking as he climbs the stairs, one cautious step at a time. He tries to tread softly as he doesn’t want to wake anyone – not yet. If it was her climbing the stairs late at night she would make it all the way up to the top without anyone hearing a thing. But he can’t do it. He doesn’t know them like she does, doesn’t know where best to tread.

She shuts her eyes, clenching them so tight that the muscles around them ache. And she takes deep, slow breaths, hoping he won’t be able to hear how fast her heart is beating. Because a heart only beats that fast when you’re awake – awake and terribly afraid. She remembers the time her father had her listen to his heart. He must have run up and down the stairs a thousand times before he’d stopped and called her over. ‘Listen!’ he’d said. ‘Listen to how fast my heart’s beating. That’s because our bodies need more oxygen when we move, and it’s our heart’s job to provide it.’ But now, although she’s lying perfectly still, her heart is pounding much faster than her father’s was then.

He’s getting closer.

She recognises the creaking of the last stair, just as she recognises the rattling the roof makes when there’s a gale blowing outside, or the squeaking of the door downstairs when her mother comes home. Tiny stars appear and float across her eyelids. They’re not like the stars in the sky: those hardly ever move, and you can only catch them at it if you watch them for a long time and you’re very lucky. She’s not lucky, though. She’s never been lucky.

She can sense him standing over her now, wheezing like an old man. The stink of cigarettes fills her nose. If she looked up she would see those dark-grey eyes staring down at her. Instinctively, she pulls the duvet a fraction higher over her face. But she can’t hide. The tiny movement will have given her away: he’ll know she’s only pretending to be asleep. Not that it will make any difference.

It’s never made any difference.2

Elma wasn’t afraid, though the feeling was similar to fear: sweaty palms, rapid heartbeat. She wasn’t nervous either. She got nervous when she had to stand up and speak in front of people. Then the blood would rise into her skin; not only on her face, where she could disguise the flush with a thick layer of make-up, but on her neck and chest as well, where it formed unsightly red-and-white blotches.

She’d been nervous that time she had gone out on a date with Steinar in year ten. A fifteen-year-old girl with a blotchy chest and far too much mascara, who had tiptoed out of the house, praying that her parents wouldn’t hear the front door closing behind her. She had waited for him to pick her up on the corner. He’d been sitting in the back of the car – he wasn’t old enough to drive yet, but he had a friend who was. They’d not driven far, and had barely exchanged a word, when he leant over and stuck his tongue down her throat. She’d never kissed anyone before but, although his tongue felt very large and invasive, she hadn’t drawn away. His friend had driven calmly around while they were kissing, though from time to time she’d caught him watching them in the rear-view mirror. She’d let Steinar touch her through her clothes too and pretended to enjoy it. They had been driving down the same road she was on now. Back then they had Lifehouse on the speakers, bass pounding from the boot. She shuddered at the memory.

There were cracks in the pavement outside her parents’ house. She parked the car and sat staring at them for a minute or two. Pictured them widening and deepening until her old Volvo was swallowed up. The cracks had been there ever since she was a little girl. They’d been less obvious then, but not much. Silja used to live in the blue house opposite, and they’d often played games on this pavement. They used to pretend that the biggest crack was a huge volcanic fissure, full of red-hot lava, and that the tongues of flame were licking up towards them.

The blue house – which wasn’t blue anymore but white – was home these days to a family with two young boys, both blond, 3with identical Prince Valiant pageboy haircuts. She didn’t know where Silja lived now. It must be four years since she’d last talked to her. Longer, perhaps.

She got out of the car and walked up to her parents’ house. Before opening the door, she glanced back down at the cracks in the pavement. Now, more than twenty years later, the thought of being swallowed up by them didn’t seem so bad.

Several Weeks Later – Saturday, 18 November 2017

Elma was woken by the wind. She lay there for a long time, listening to it keening outside her window as she stared up at the white ceiling of her flat. When she finally got out of bed it was too late to do anything but mindlessly pull on some clothes and grab a blackened banana on her way out of the door. The bitter wind cut into her cheeks the moment she stepped outside. She zipped her coat to the neck, pulled up her hood and set off through the darkness at a brisk pace. The glow of the streetlights lit up the pavement, striking a sparkle from the grey tarmac. The frost creaked under her shoes, echoing in the silence – there were few people about on a Saturday morning in mid-November.

A few minutes after leaving the warmth of her flat, she was standing in front of the plain, pale-green building that housed Akranes Police Station. Elma tried to breathe calmly as she took hold of the icy door handle. Inside, she found herself in front of a reception desk where an older woman with curly blonde hair and a tanned, leathery face was talking on the phone. She held up a finger with a red-varnished nail as a sign for Elma to wait.

‘All right, Jói, I’ll tell him. I know it’s unacceptable, but it’s hardly a police matter – they’re feral cats, so I recommend you get in touch with the pest controller … Anyway, Jói…’ The woman held the telephone receiver a fraction away from her ear and smiled apologetically at Elma. ‘Listen, Jói, there’s not much I can do about that now. Just remember to close the window next time you go to the shops … Yes, I know those Moroccan rugs cost a fortune. Listen, Jói, we’ll have to discuss it later. I’ve got to go now. Bye.’

She put down the receiver with a sigh. ‘The feral-cat problem in Neðri-Skagi is beyond a joke. The poor man only left his window open while he popped out to the shop, and one of the little beasts got in there and peed and crapped on the antique rug 5in his sitting room. Poor old boy,’ the woman said, shaking her head. ‘Anyway, enough about that, what can I do for you, dear?’

‘Er, hello.’ Elma cleared her throat, remembering as she did so that she hadn’t brushed her teeth: she could still taste the banana she’d eaten on her walk. ‘My name’s Elma. I’ve got an appointment with Hörður.’

‘Oh, yes, I know who you are,’ the woman said, standing up and holding out her hand. ‘I’m Guðlaug, but please call me Gulla. Come on in. I’d advise you to keep your coat on. It’s freezing in reception. I’ve been on at them for weeks to repair that radiator, but apparently it’s not a priority for a cash-strapped police force.’ She sounded fed up about this, but then went straight on in a brighter voice: ‘How are your parents, by the way? They must be so pleased to have you home again, but then that’s how it is with Akranes: you just can’t beat it, and most people come back once they realise the grass isn’t greener down south in Reykjavík.’ She produced all this in a rush, barely pausing for breath. Elma waited patiently for her to finish.

‘They’re fine,’ she said as soon as she could get a word in, all the while racking her brains to remember if Gulla was someone she ought to know. Ever since she’d moved back to Akranes five weeks earlier, people she didn’t recognise had been stopping her in the street for a chat. Usually it was enough to nod and smile.

‘Sorry,’ Gulla added. ‘I tend to let my tongue run away with me. You’ll get used to it. You won’t remember me, but I used to live in the same terrace as you when you were a little thing, only six years old. I still remember how sweet you looked weighed down by that great big backpack on your first day at school.’ She laughed at the memory.

‘Oh, yes … that sounds vaguely familiar – the backpack, I mean,’ Elma said. She dimly recalled a big yellow burden being loaded onto her shoulders. It can’t have weighed less than a quarter of her bodyweight at the time.

‘And now you’re back,’ Gulla went on, beaming.6

‘Yes, it looks like it,’ Elma said awkwardly. She hadn’t been prepared for such a warm welcome.

‘Right, well, I suppose I’d better take you straight through to see Hörður; he told me he was expecting you.’ Gulla beckoned her to follow, and they walked down a linoleum-floored corridor and came to a halt outside a door where ‘Hörður Höskuldsson’ was engraved on a discreet metal nameplate.

‘If I know Hörður, he’ll be listening to the radio with his headphones on and won’t be able to hear us. The man can’t work without those things in his ears. I’ve never understood how he can concentrate.’ Gulla gave a loud sigh, rapped smartly on the door, and opened it without waiting for a response.

Inside, a man was sitting behind a desk, staring intently at his computer screen. The headphones were in place, as Gulla had predicted. Noticing movement, he looked up and quickly took them off.

‘Hello, Elma. Welcome,’ he said with a friendly smile. Rising to his feet, he extended a hand across his desk, then gestured to her to take a seat. He looked to be well over fifty, with greying hair hanging in untidy locks on either side of his long face. In contrast, his fingers were elegant, with neatly manicured nails. Elma pictured him sitting in front of the TV in the evenings, wielding a nail file, and instinctively hid her own hands in her lap so he wouldn’t see her bitten-down cuticles.

‘So, you’ve decided to move back to Akranes and give us the benefit of your expertise,’ he said, leaning back with his fingers clasped across his chest as he studied her. He had a deep voice and unusually pale blue eyes.

‘Well, I suppose you could put it like that,’ Elma said, straightening her shoulders. She felt like a little girl who had done something naughty and been summoned to the headmaster’s office. Feeling her cheeks growing hot, she hoped he wouldn’t notice their betraying flush. There was every chance he would though, as she hadn’t had time to slap on any foundation before coming out.7

‘I’m aware you’ve been working for Reykjavík CID. As luck would have it, one of our boys has decided to try his chances in the big city, so you’ll be taking over his desk.’ Hörður leant forwards, propping his cheek on one hand. ‘I have to admit I was quite surprised when I got the call from your father. What made you decide to come back here after so many years in the city, if you don’t mind my asking?’

‘I suppose I was missing Akranes,’ Elma replied, trying to make it sound convincing. ‘I’d been thinking about moving home for ages,’ she elaborated. ‘My whole family’s here. Then a flat I liked the look of came on the market, and I jumped at the chance.’ She smiled, hoping this answer would do.

‘I see,’ Hörður said, nodding slowly. ‘Of course, we can’t offer you quite the same facilities or fast pace as you’re used to in town,’ he continued, ‘but I can promise you that, although Akranes seems quiet, we’ve actually got more than enough on our plate. There’s plenty going on under the surface, so you won’t be sitting around twiddling your thumbs. Sound good to you?’

Elma nodded, unsure if he was being serious. In her opinion Akranes was every bit as quiet as it appeared to be.

‘As you probably know,’ Hörður said, ‘I’m head of CID here, so you’ll be working under me. We operate a shift system, with four officers on duty at any given time, and a duty officer in charge of every shift. Here at Akranes CID we’re responsible for the entire Western Region. We operate the usual day-shift rota that you’ll be used to from Reykjavík. Shall I give you a quick tour of the station?’ He got up, went over to the door and, opening it, beckoned Elma to follow him.

Apart from being considerably smaller, Akranes Police Station was much like her old workplace in the city. It had the same institutional air as other public-sector offices: beige linoleum on the floor, white roller blinds in the windows, light-coloured curtains, blond birchwood furniture.

Hörður pointed out the four holding cells at the other end of 8the station. ‘One of them’s occupied at the moment. Yesterday seems to have been a bit lively for some people, but hopefully the guy will wake up soon, and we can send him home.’ He smiled absently, stroking the thick, neatly trimmed stubble on his jaw. Then he opened the door to reveal an empty cell, which looked pretty much like the cells in Reykjavík: a small, rectangular room containing a narrow bed.

‘The standard set-up, nothing that exciting,’ he said.

Elma nodded again. She’d lost count of the times she’d seen the same kind of cells in the city: grey walls and hard beds that few people would want to spend more than one night on. She followed Hörður back down the corridor, which now gave way to offices. He stopped by a door, opened it and ushered her inside. She glanced around. Although the desk was small, it had plenty of room for a computer and anything else she might need, and had lockable drawers too. Someone had put a pot plant on it. Fortunately it appeared to be some kind of cactus that would require little care. Then again, she’d managed to kill even cactuses before now.

‘This is where you’ll be kicking your heels,’ Hörður said with a hint of humour. ‘Gulla cleaned it out a few days ago. Pétur, your predecessor, left behind a mountain of files and other junk, but I think it should be ready for you to start work on Monday.’

‘Looks good,’ Elma said, smiling at him.

She went over to the window and stared out. A chill came off the glass and she could feel the goose bumps prickling her arms. The view was depressing: a row of dreary modern blocks of flats. When she was small she used to play in the basements of those buildings. The corridors had been wide and empty, and smelled of stale air and the rubber of the car tyres stored in the bike sheds. A perfect playground for kids.

‘Right, well, that’s pretty much everything,’ Hörður said, rubbing his hands. ‘Shall we check if the coffee’s ready? You must have a cup with us before you go.’9

They went into the kitchen, where a man, who introduced himself as Kári, one of the regular uniformed officers, was sitting at a small table. He explained that the other members of his shift were on a callout – a party at one of the residential blocks had gone on until morning, to the dismay of the neighbours.

‘Welcome to the peace and quiet of the countryside,’ Kári said. When he grinned, his dark eyes creased up until all that could be glimpsed of them were his glittering black pupils. ‘Not that you can really call it the countryside anymore, after all the development we’ve seen around here. Houses are flying off the market. Apparently everyone wants to live in Akranes these days.’ He gave a loud bark of laughter.

‘It’ll make a change, anyway,’ Elma replied, and couldn’t help grinning back. The man looked like a cartoon character when he laughed.

‘It’ll be good to have you on the team,’ Hörður said. ‘To be honest, we were a bit worried about losing Pétur, as he was one of the old hands. But he wanted a change of scene after more than twenty years here. He’s got a wife in Reykjavík now, and both his children have flown the nest.’ Hörður filled two cups with coffee and handed one to her. ‘Do you take milk or sugar?’ he asked, holding out a purple carton.

Akranes 1989

Her daddy hadn’t come home for days and days. She had given up asking where he was. Her mummy got so sad when she did. Anyway, she knew he wasn’t coming back. For days she had watched people coming and going, heard them talking to each other, but no one told her anything. They looked at her and patted her on the head, but avoided meeting her eye. She could guess what had happened, though, from the little she had overheard. She knew her daddy had gone out on the boat the day he left. She had heard people talking about the shipwreck and the storm; the storm that had taken her daddy away.

The night he vanished she had been woken by the wind tearing at the corrugated-iron sheets on the roof as if it wanted to rip them off. Her daddy had been in her dream, as large as life, with a big smile on his face and beads of sweat on his forehead. Just like in the summer, when he’d invited her to come out on the boat with him. She had been thinking about him before she went to sleep. Once, her daddy had told her that if you think nice thoughts before you go to bed, you’ll have nice dreams. That’s why she’d been thinking about him: he was the nicest thing she could imagine.

Days passed and people stopped coming round. In the end it was just the two of them, just her and her mummy. Her mummy still wouldn’t tell her anything, no matter how often she asked. She would answer at random, waving her away and telling her to go out and play. Sometimes her mummy sat for a long time, just staring out of the window at the sea, while she smoked an awful lot of cigarettes. Lots more than she used to. She wanted to say something nice to her mummy, say that perhaps Daddy was only lost and would find his way home. But she didn’t dare. She was afraid her mummy would get cross. So she stayed quiet and did as she was told, like a good little girl. Went out to play, spoke as little as possible and tried to be invisible at home so her mummy wouldn’t be annoyed.

And all the while her mummy’s tummy kept growing bigger and bigger. 11

The sky was growing perceptibly paler by the time Elma re-emerged from the police station, though the streetlights were still on. There were more cars on the roads now and the wind had dropped. Since returning to her old hometown on the Skagi Peninsula, she had been struck by how flat and exposed it seemed in comparison to Reykjavík. Walking through its quiet streets, she felt as if there was nowhere to hide from prying eyes. Unlike the capital, where trees and gardens had grown up over the years to soften the urban landscape and shelter the inhabitants from Iceland’s fierce winds, Akranes had little in the way of vegetation, and the impression of bleakness was made worse by the fact that many of the houses and streets were in poor repair. No doubt the recent closure of one of the local fish factories had contributed to the air of decline. But the surrounding scenery still took Elma’s breath away: the sea on three sides; Mount Akranes, with its distinctive dip in the middle, dominating the fourth. Ranks of mountains marching away up the coast to the north; the glow of Reykjavík’s lights visible across Faxaflói Bay to the south.

Akranes had changed since she was a little girl. It had spread and its population had grown, yet in spite of that she felt it was fundamentally the same. It was still a small town of only seven thousand or so inhabitants, and you encountered the same faces day in, day out. Once she had found the idea stifling, like being trapped in a tiny bubble when there was so much more out there to discover. But now the prospect had the opposite effect: she had nothing against the idea of retreating into a bubble and forgetting the outside world.

She walked slowly, thinking of all the jobs that awaited her at home. She was still getting settled in, having only picked up the keys to her flat the previous weekend. It was in a small block with seven other apartments on two floors. When Elma was a girl, there hadn’t been any buildings there, just a large field that sometimes contained horses, which she used to feed with stale bread. But since then a whole new neighbourhood had sprung 12up, consisting of houses and apartment blocks and even a nursery school. Her flat was on the ground floor and had a large deck out front. There were two staircases in the building, with four flats sharing the small communal area on each. Elma hadn’t met her neighbours properly, though she did know that there was a young man living opposite her, who she hadn’t yet seen. Upstairs was an older man called Bárður, chairman of the residents’ association, and a childless, middle-aged couple who gave her friendly nods whenever they met.

She had spent the week decorating the flat, and now most of the furniture was in place. The contents were a bit of a mixed bag. She’d picked up all kinds of stuff from a charity shop, including an old chest with a carved floral pattern, a gold-plated floor lamp, and four kitchen chairs that she had arranged around her parents’ old dining table. She’d thought the flat was looking quite cosy, but when her mother came round, her expression had indicated that she didn’t agree. ‘Oh, Elma, it’s a bit … colourful,’ she had said in an accusatory tone. ‘What happened to all the furniture from your old flat? It was so lovely and tasteful.’

Elma had shrugged and pretended not to see her mother’s face when she announced casually that she’d sold it when she moved. ‘Well, I hope you at least got a decent price for it,’ her mother had said. Elma had merely smiled, as this couldn’t have been further from the truth. Besides, she liked being surrounded by these old, mismatched pieces; some were familiar from her childhood, others felt as if they probably came with a story attached.

Before moving here, she had lived with Davíð, her boyfriend of many years, in the desirable west end of Reykjavík. Their flat, which was small but cosy, had been in the Melar area, on the middle floor of a three-storey building. She missed the tall rowan tree outside the window. It had been like a painting that changed colour with the seasons, bright green in summer, reddish-orange in autumn and either brown or white in winter. She missed the flat too, but most of all she missed Davíð.13

She stopped outside the door of her flat, took out her phone and wrote a text message. Deleted it, then wrote the same message again. Stood there without moving for a moment, then selected Davíð’s number. She knew it wouldn’t do any good but she sent the message anyway, then went inside.

It was Saturday evening and Akranes’s most popular restaurant was packed out, but then there wasn’t much competition. Despite the unpromising exterior, it was contemporary and chic inside, with black furniture, grey walls and flattering lighting. Magnea sat up a little straighter as she surveyed the other diners. She knew she was looking her best this evening in a figure-hugging black jumpsuit and was conscious of all the eyes straying inadvertently to her cleavage. Bjarni was sitting opposite her, and whenever their gazes met she read the promise in his eyes about what would happen once they got home. She would have given anything to be dining alone with him instead of having his parents seated either side of her.

They were celebrating the fact that Bjarni was finally taking over the family firm. He had been employed there ever since he finished school, but despite being the boss’s son, he had been forced to work hard for the title of managing director. He’d put in a huge number of hours, often working evenings and weekends, and had, in practice, been running the firm alongside his father for several years. But now, at last, it was official: he was formally taking over as managing director. This meant double the salary and double the responsibility, but this evening, at least, he was determined to relax.

The waiter brought a bottle of red wine and poured a splash into Bjarni’s glass. After he had tasted it and signalled his approval, the waiter filled their glasses, then retreated, leaving the bottle behind on the table.

‘Skál!’ Bjarni’s father, Hendrik, raised his glass. ‘To Bjarni and 14his unstoppable energy. Now he can add the title of managing director to his list of achievements. As his parents, we’re hugely proud of him, as we always have been.’

They clinked glasses and tasted the expensive wine. Magnea was careful to take only a tiny sip, allowing no more than a few drops to pass between her red-painted lips.

‘I wouldn’t have got where I am today without this gorgeous girl beside me,’ Bjarni said, his voice slurring a little. He’d had a whisky while they were waiting for his parents and, as always when he drank spirits, the alcohol had gone straight to his head. ‘I’ve lost count of the times I’ve come home late from the office and never, not once, has my darling wife complained, although she has more than enough to do at work herself.’ He gazed adoringly at Magnea and she blew him a kiss over the table.

Hendrik turned an indulgent look on Ása but, instead of returning his smile, she averted her eyes, her mouth tight with disapproval. Magnea sighed under her breath. She had given up trying to win her mother-in-law round. These days she didn’t really care anymore. When she and Bjarni had first moved in together she had made a real effort to impress Ása, making sure the house was immaculate whenever his parents were coming over, baking specially for them and generally bending over backwards to earn her mother-in-law’s approval. But it had been a lost cause. Her efforts were invariably rewarded with the same critical look; the look that said the cake was too dry, the bathroom wasn’t sufficiently sparkling clean and the floors could have done with another going over. The message was clear: however hard she tried, Magnea would never be good enough for Bjarni.

‘How’s the teaching going, Magnea?’ Hendrik asked. ‘Are those brats behaving themselves?’ Unlike his wife he had always had a soft spot for his daughter-in-law. Perhaps that was one reason for Ása’s hostility. Hendrik never missed a chance to touch Magnea, put an arm round her shoulders or waist, or kiss her on the cheek. He was a big man, in contrast to his dainty 15wife, and had a reputation in Akranes as a bit of a shark when it came to business. He had a charming smile that Bjarni had inherited, and a powerful, slightly husky, voice. Regular drinking had turned his features coarse and red, yet Magnea liked him better than Ása, so she put up with the wandering hands and the flirtation, which all seemed harmless enough to her.

‘They usually behave themselves for me,’ Magnea replied, smiling at him. At that moment the waiter came back to take their order.

The evening went pretty smoothly: Bjarni and Hendrik chatted about work and football; Ása sat in silence, apparently sunk in her own thoughts, and Magnea smiled at the two men from time to time, contributing the odd word, but otherwise sat quietly like Ása. It was a relief when the meal was over and they could leave. The cold night air sneaked inside her thin coat once they were outside and she took Bjarni’s arm, pressing close to him.

They had the rest of the evening to themselves.

It wasn’t until Bjarni had fallen asleep beside her in bed that she remembered the face. She saw again the pair of dark eyes that had met hers when she glanced across the restaurant. For much of the night she lay wide awake, trying to ward off the memories that flashed into her mind with a stark clarity every time she closed her eyes.

Monday, 20 November 2017

Elma sat at her new desk in her new office, on her first day, trying to keep her eyes open. Conscious that she was slouching, she straightened up and forced herself to focus on the computer screen. She had spent the previous evening wandering restlessly around her flat before deciding on an impulse to paint the sitting room. The tins of emulsion had been sitting there untouched ever since she moved in. As a result, she hadn’t crashed out until the early hours, too exhausted to scrub the paint spots off her arms.

Remembering the text message she had sent Davíð, she pictured him opening it and the faintest smile touching his lips before he sent a reply. But that was wishful thinking; she knew he wouldn’t answer. She briefly closed her eyes, feeling her breath coming fast and shallow, and experiencing again that suffocating sensation as if the walls were closing in on her. She concentrated on taking deep, slow breaths.

‘Ahem.’

She opened her eyes. A man was standing in front of her, holding out his hand. ‘Sævar,’ he said.

Elma hastily pulled herself together and shook his large, hairy hand, which turned out to be unexpectedly soft.

‘I see they’ve found a home for you.’ Sævar smiled at her. He was wearing dark-blue jeans and a short-sleeved shirt that revealed the thick fur on his arms. The overall impression – dark hair, dense stubble, heavy eyebrows and coarse features – was that of a caveman, but this was belied by a pleasant hint of aftershave.

‘Yes, it’s not bad. Pretty good, actually,’ Elma said, brushing her hair back from her face.

‘How are you enjoying life out here in the sticks?’ Sævar asked, still smiling. He must be the other detective Hörður had mentioned. Elma knew he’d been working for the Akranes force since 17he was twenty but didn’t recall seeing his face before, though he couldn’t have been more than a few years older than her. The town only had two schools and one community college, and the smallness of the place meant that you generally encountered all your contemporaries sooner or later – or so Elma had thought.

‘Very much,’ she replied, trying to sound upbeat but afraid she was coming across as a bit of an idiot. She hoped the black circles under her eyes weren’t too obvious but knew the unforgiving fluorescent lights would only exaggerate any signs of weariness.

‘I hear you were in Reykjavík CID,’ Sævar continued. ‘What made you decide to have a change of scene and come here?’

‘Well, I grew up here,’ Elma said, ‘so … I suppose I was missing my family.’

‘Yes, that’s the most important thing in life,’ Sævar said. ‘You realise when you start to get old that family’s what it’s all about.’

‘Old?’ Elma looked at him in surprise. ‘You can’t be that old.’

‘No, maybe not.’ Sævar grinned. ‘Thirty-five. Best years still to come.’

‘I certainly hope so,’ Elma said. As a rule, she tried not to dwell on her age. She knew she was still young, and yet she was uncomfortably aware of how fast the years were winging by. If anyone asked how old she was, she almost always had to stop and think, so she tended just to give the year of her birth – her vintage. As if she were a car or a wine.

‘That makes two of us,’ Sævar said. ‘Anyway, the reason I’m here is that we got a callout at the weekend after some people heard a woman screaming in the flat upstairs, and a lot of shouting and banging. When we got there, it was a mess. The man had beaten his girlfriend so badly his knuckles were bleeding. The woman insisted she didn’t want to take it any further, but I expect charges will be brought anyway. Still, it helps if the victim’s prepared to testify, even when we have a medical report and other evidence to back up our case. She’s home from hospital now, and I was thinking of having a chat with her, but I reckon it would be better 18to have a female officer present. And it wouldn’t hurt if she’d studied psychology as well,’ he added, with a twinkle in his eye.

‘It was only for two years,’ Elma muttered, wondering how he knew about the psychology degree she had been taking before she dropped out of university and enrolled at the Police College instead. She didn’t remember the subject coming up in conversation, so presumably he must have read her CV. ‘Sure, I’ll go with you but I can’t promise my knowledge of psychology will be any use.’

‘Oh, come on – I have complete faith in you.’

They were met by a strong smell of cooking when they knocked on the door of the house. After a bit of a wait they heard signs of life inside. Sævar had told Elma on the way there that the woman they wanted to see was currently staying with her elderly grandmother.

A few moments later the door opened with a feeble creak, and a small, wizened woman with a deeply lined face appeared in the gap. Her skin was covered in brown liver spots but the pale-grey, shoulder-length hair, drawn back in a clip, was unusually thick and handsome for her age. She raised her eyebrows inquiringly.

‘We’re looking for Ásdís Sigurðardóttir. Is she in?’ Sævar asked. The old woman turned round without a word, beckoning them to follow her.

Elma guessed the house hadn’t changed much since it was built, probably in the seventies. There was a carpet on the floor – a rare sight in Iceland where they were considered old-fashioned and unhygienic – and the walls were clad in dark wood panelling. The smell of meat stew was even more overpowering inside.

‘That arsehole,’ the old woman burst out, startling Elma. ‘That pathetic bastard can rot in hell for all I care. But Dísa won’t listen to me. Won’t even discuss it. So I told her she could pack her 19bags. If she won’t listen, she can get out of my house.’ The old woman turned without warning and took hold of Elma’s arm. ‘But I can’t talk – I’ve always been a soft touch myself, so she probably got it from me. I can’t throw her out, not after what’s happened. But maybe you can get through to her. She’s in there, in her old room.’ She pointed down the hallway with a knobbly, brown-splotched hand, then shuffled off and left them to it, muttering under her breath.

Elma and Sævar stood there for a moment, trying to work out which door she had meant. There were four rooms opening off the hallway and Elma wondered how the old woman could afford such a large house when, as far as they knew, she usually lived there alone. After a moment, Sævar tapped tentatively on one of the doors. When there was no response, he opened it warily.

The girl sitting on the bed was considerably younger than Elma had been expecting. She was hunched over the computer in her lap but raised her head as they entered. She couldn’t have been more than twenty-five, and her dark-blue hoodie and white pyjamas with a pink pattern contributed to the impression of youth. Her eyebrows were pencilled black and looked much darker than her brown hair, which was scraped back in a lank pony-tail. But it was hard to take in anything apart from her battered face. Her lips had split and the swelling round her eyes was mottled blue, green and brown.

‘May I?’ Elma asked, gesturing to the office chair at the end of the bed. She and Sævar had agreed beforehand that she would do most of the talking. The girl was bound to find it easier to speak to a woman after what that man had done to her. When the girl nodded, Elma sat down.

‘Do you know who I am?’ she asked.

‘No, how should I know that?’

‘I’m from the police. We’re assisting the prosecutor with the case against your boyfriend.’ 20

‘I’m not pressing charges. I told them that at the hospital.’ Her voice was firm and uncompromising. As she spoke, she sat up a little straighter.

‘I’m afraid it’s out of your hands,’ Elma said, trying to sound friendly, and explained: ‘When the police are involved, they have the power to investigate the incident and prosecute if they deem it necessary.’

‘But you don’t understand … I don’t want to prosecute,’ the girl said angrily. ‘Tommi’s just … he’s been having a hard time. He didn’t mean to do it.’

‘I see, but that’s still no excuse for what he did to you. Lots of us have problems but we don’t all react like that.’ Elma leant forward in her chair, holding Ásdís’s gaze with her own. ‘Has he done it before?’

‘No,’ the girl answered quickly, before qualifying in a low voice: ‘He’s never hit me before.’

‘The doctor found old bruises on you. Bruises from about a month ago.’

‘I don’t know what can have caused them, but then I’m always falling over,’ Ásdís retorted.

Elma studied her searchingly, reluctant to put too much pressure on her. She looked so small and vulnerable as she sat there in bed, in clothes that seemed far too big for her.

‘He’s almost forty years older than you, isn’t he?’

‘No, he’s sixty. I’m nearly twenty-nine,’ the girl corrected her.

‘It would really help if you’d come down to the station with us so we could take a formal statement from you,’ Elma said. ‘Then you’d get a chance to put your side of the story.’

Ásdís shook her head, stroking the initials embroidered on the duvet cover. They looked to Elma like Á.H.S.

‘You know, there’s all kinds of help available to women in your situation,’ Elma continued. ‘We’ve got a counsellor you could talk to and there’s a women’s refuge in Reykjavík that’s helped lots of…’ Elma trailed off when she caught the look on Ásdís’s face. 21

‘What does the H stand for?’ she asked instead, after a brief pause.

‘Harpa. Ásdís Harpa. But I’ve always hated the name. My mother was called Harpa.’

Elma didn’t pursue the subject. There must be some reason why Ásdís couldn’t stand being named after her mother, even though the woman was dead. And why, at nearly thirty, she was still living sometimes with her grandmother, sometimes with a much older man who treated her like a punch bag. But sadly Elma had seen many worse cases and could tell straight away that there was little to be done until Ásdís was prepared to take action herself. Elma just hoped she wouldn’t leave it too late. Ásdís had turned her attention back to her laptop as if there was no one else in the room. Elma raised her eyebrows at Sævar with a defeated look and got to her feet. There was no more to be said.

Nevertheless, as they were leaving she paused in the doorway and turned: ‘Are you going back to him?’

‘Yes,’ Ásdís replied, without looking up from the screen.

‘Well, good luck. Don’t hesitate to call if … if you need us,’ Elma said, putting out a hand to close the door.

‘You lot don’t understand anything,’ Ásdís muttered angrily. Elma stopped and looked round again. Ásdís hesitated, then added in a low voice: ‘I can’t press charges; I’m pregnant.’

‘All the more reason to stay out of his way, then,’ Elma said, meeting her eye. She spoke slowly and deliberately, stressing every syllable in the hope that her words would sink in. But she didn’t really believe they would.

It was past four and already getting dark outside when Elma wandered into the kitchen. The coffee in the thermos turned out to be lukewarm and tasted as if it had been sitting there since that morning. She tipped the contents of her mug down the sink and started opening the cupboards in search of tea. 22

‘The tea’s in the drawer,’ said a voice behind her, making her jump. It was the young female officer Elma had been introduced to earlier that day. Elma struggled for her name: Begga, that was it. She looked quite a bit younger than Elma herself; well under thirty, anyway. She was tall and big-boned, with shoulder-length, mousy hair and a nose that wouldn’t have looked out of place on a Roman emperor. Elma noticed that she had dimples even when she wasn’t smiling.

‘Sorry, I didn’t mean to startle you,’ Begga said. She pulled open a drawer and showed Elma a box of tea bags.

‘Thanks,’ Elma said. ‘Would you like some too?’

‘Yes, please. I may as well join you.’ Begga sat down at the little table. Elma waited for the kettle to boil, then filled two mugs with hot water. She fetched a carton of milk from the fridge and put it on the table along with a bowl of sugar-lumps.

‘I know you from somewhere.’ Begga studied Elma thoughtfully as she stirred her tea. ‘Were you at Grundi School?’

Elma nodded. She’d attended the school, which was on the southern side of town.

‘I think I remember you. You must have been a couple of years above me. Were you born in 1985?’

‘Yes, I was,’ Elma said, sipping from her steaming mug. Begga was much older than she’d guessed; almost as old as her.

‘I do remember you,’ Begga said, her dimples becoming more pronounced as she smiled. ‘I was so pleased to hear there was another woman joining us. As you may have noticed, we’re in a serious minority here. It’s a bit of a man’s world.’

‘It certainly is. But I like working with these guys so far,’ Elma said. ‘They seem really easy to get along with.’

‘Yes, most of them. I’m happy here anyway,’ Begga said. She was one of those people who appear to be perpetually smiling, even when they aren’t. She had that sort of face.

‘Have you always lived here?’ Elma asked.

‘Yes, always,’ Begga replied. ‘I love it here. The locals are great, 23there’s no traffic and everything’s within reach. I’ve no reason to go anywhere else. And I’m absolutely sure my friends who’ve moved away will come back eventually. Most people who leave come back sooner or later,’ she added confidently. ‘Like you, for example.’

‘Like me, for example,’ Elma repeated, dropping her gaze to her mug.

‘Why did you decide to move back?’ Begga prompted.

Elma wondered how often she would have to answer this question. She was about to trot out the usual story when she paused. Begga had the sort of comfortable manner that invited confidences. ‘I was missing my family, and it’s good to get away from the traffic, of course, but…’ She hesitated. ‘Actually, I’ve just come out of a relationship.’

‘I see.’ Begga pushed over a basket of biscuits, taking one herself as she did so. ‘Had you been together long?’

‘I suppose so – nine years.’

‘Wow, I’ve never managed more than six months,’ Begga exclaimed with an infectious giggle. ‘Though I am closely involved with a gorgeous guy at the moment. He’s very fluffy and loves cuddling up to me in the evenings.’

‘A dog?’ Elma guessed.

‘Nearly.’ Begga grinned. ‘A cat.’

Elma smiled back. She had taken an instant liking to Begga, who didn’t seem to care what other people thought of her. She was different, without making any conscious effort to be.

‘So, what happened?’ Begga asked.

‘When?’

‘With you and the nine-year guy.’

Elma sighed. She didn’t want to have to think about Davíð now. ‘He changed,’ she said. ‘Or maybe I did. I don’t know.’

‘Did he cheat on you? The guy I was seeing for six months cheated on me. Well, he didn’t actually shag someone else, but I found out he was using dating sites and had a Tinder profile. I came across it by chance.’ 24

Elma caught her eye. ‘So you were on there yourself?’

‘Yeah, but only for research purposes. It was purely academic interest,’ Begga said with mock seriousness. ‘You should try it. It’s brilliant. I’ve already been on two Tinder dates.’

‘How did they go?’

‘It worked the second time – if you know what I mean.’ Begga winked at her and Elma laughed in spite of herself. ‘But I’m not actually looking for anyone,’ Begga went on. ‘I enjoy the single life. For the moment, anyway. And my heart belongs to my liddle baby.’

‘Your baby?’

‘Yeah, my boy cat,’ Begga explained and burst out laughing.

Elma rolled her eyes and smiled. Begga was one of a kind all right.

Akranes 1989

The baby came in May. The day it was born was beautiful and sunny, with barely a cloud in the sky. When she went outside the air was damp from the night’s rain and the spicy scent of fresh greenery hung over the garden, tickling her nose. The sea stirred idly and far beyond the bay she could see the white dome of the Snæfellsjökull glacier rising on the horizon. Closer at hand, the reefs peeped up from the waves every now and then. She was wearing a pair of snow-washed jeans and a yellow T-shirt with a rainbow on the front. Her hair was tied back in a loose pony-tail but her curls kept escaping from the elastic band, so she was constantly having to brush strands of hair from her face.

It was a Saturday and they had woken early, then eaten toast and jam for breakfast while listening to the radio. The weather was so good that they decided they would go for a walk on the beach to look for shells. They found an empty ice-cream tub to take with them and she sat on the swing while waiting for her mummy to finish her chores. As her mummy hung out the washing, she swung back and forth, reaching her toes up to the sky. They were chatting and her mummy was just smiling at her and stretching her arms to hang up a white sheet when suddenly she clutched at her stomach and doubled over. She stopped her swinging and watched her mummy anxiously.

‘It’s all right. Just a bit of a twinge,’ her mummy said, trying to smile. But when she stood up, the pain started again and she had to sit down on the wet grass.

‘Mummy?’ she said anxiously, going over to her.

‘Run next door to Solla’s and ask her to come over.’ Her mother took a deep breath and made a face. Drops of sweat trickled down her forehead. ‘Hurry.’

Without waiting to be told again, she ran as fast as she could across the road to Solla’s house. She knocked on the door, then opened it without waiting for an answer.26

‘Hello! Solla!’ she shouted. She could hear voices coming from the radio, then a figure appeared in the kitchen doorway.

‘What’s up?’ Solla asked, regarding her in surprise.

‘The baby…’ she panted. ‘It’s coming.’

Several days later her mummy came home with a small bundle wrapped in a blue blanket. He was the most beautiful thing she had ever seen, with his dark hair and plump, unbelievably soft cheeks. Cautiously, she stroked the tiny fingers and marvelled that anything could be that small. But best of all was the smell. He smelled of milk and something sweet that she couldn’t put a name to. Even the little white pimples on his cheeks were so tiny and delicate that it was a sheer pleasure to run your finger over them. He was to be called Arnar, just like her daddy.

But her beautiful little brother only lived for two weeks in their house by the sea. One day he wouldn’t wake up, however hard her mummy tried to rouse him.

Saturday, 25 November 2017

The only sounds in the house were the ticking of the sitting-room clock and the regular clicking of her knitting needles as they turned out the smooth, pale loops. The little jumper was almost finished. Once Ása had cast off and woven in the loose ends, she laid the jumper on the sofa and smoothed it out. The yarn, a mix of alpaca and silk, was as soft and light as thistledown. She tried out several different kinds of buttons against the jumper before opting for some white mother-of-pearl ones that went well with the light-coloured wool. She would sew them on later, once she had washed it. After putting the little garment in the washing machine, she switched on the kettle, scooped up some tea leaves in the strainer, poured the boiling water over them and added sugar and a dash of milk. Then she sat down at the kitchen table. The weekend paper lay there unopened, but instead of leafing through it, she cradled the hot cup in both hands and stared unseeingly out of the window.

Her hands always got so cold when she was knitting. She wound the yarn so tightly round her index finger that it was bloodless and numb by the time she put down her needles. But knitting was her hobby, and numb fingers were a small price to pay for the pleasure she derived from seeing the yarn transformed into a succession of pretty garments. Pretty garments to add to the pile in the wardrobe. Hendrik was always grumbling about her extravagance. The yarn didn’t come cheap, especially the finest-quality soft wool, spun with silk. But she carried on regardless, ignoring Hendrik’s nagging. It wasn’t as if they couldn’t afford it. All her life she had been thrifty and watched every penny. It was how she had been brought up. But these days they had plenty of money; so much more than they needed, in fact, that she didn’t know what to do with it all. So she bought wool. She wondered at times if she should sell the clothes or give them away so others could make use of them, but something always held her back.28

She gazed out at the garden, where the blackbirds were hopping among the shrubs, attracted by the apples she had hung out for them. Time seemed to stand still. Ever since she had given up work, the days had become so long and drawn out that it was as if they would never end.

Ása heard the front door open and close, then Hendrik walked into the kitchen without a word of greeting. He was still going into the office every day, and Ása doubted he would ever give up work entirely, though he was intending to cut down now that Bjarni was taking over. When not at work, he spent most of his time on the golf course, but golf had always bored her rigid.

‘What’s the matter with you?’ Hendrik sat down at the table and picked up the paper, not looking at her as he spoke.

Ása didn’t answer but went on staring out of the window. The blackbirds were noisy now, singing shrill warning notes from the bushes. Ever louder and more insistent.

Hendrik shook his head and snorted, as if to say that it didn’t matter how she was feeling or what she was thinking.

Without a word, she slammed down her cup so violently that the tea splashed onto the table. Then she stood up and walked quickly into the bedroom, pretending not to notice Hendrik’s astonished expression. Sitting down on the bed, she concentrated on getting her breathing under control. She wasn’t accustomed to losing her temper like that. She had always been so docile, so self-effacing, first as a little girl growing up in the countryside out east and later as a woman working in the fish factory in Akranes. She had moved young to Reykjavík and, like so many country girls, attended the Home Economics School. While boarding there she had soon discovered that life in the city offered all kinds of attractions that the countryside didn’t, like new people, work and a variety of entertainment. Shops, schools and streets that hardly ever emptied. Lights that lit up the night and a harbour full of ships. It was meeting Hendrik that had brought her to Akranes. He had been working on a fishing boat 29that put into Reykjavík harbour one August night. The crew had gone out on the town where Ása was partying with her friends from the Home Economics School. She had met him as he walked in through the door of the nightclub.

Ása had known from the first instant that she had found her husband, the man she wanted to spend the rest of her life with – Him with a capital H. He was tall and dark, and the other girls had gazed at him enviously. This was hardly surprising as she had never been considered much to look at herself, with her ginger hair and her complexion that burst out in freckles at the first hint of summer.

Thinking about it later, she was convinced it was her vulnerability that had attracted him. He had seen that she was a girl who wouldn’t stand up for herself. Instead, she smiled shyly and folded her arms meekly across her stomach; she always laid the table and never walked ahead of him when they were out; she ironed his shirts without having to be asked or ever being thanked. When she and Hendrik had first got to know each other, he had said that her timidity was one of the things that had captivated him. He couldn’t stand strident women, referring to them as ‘pushy cows’, but she was a girl after his own heart, who knew when to keep quiet and let others do the talking. Who was nice and submissive. Who would make a good mother.

She wiped away the tears as they spilled over. What on earth was the matter with her? Why was she suddenly so easily upset? After all, she had coped with so much over the years. And she had Bjarni. He hadn’t been a bad son to her – quite the opposite. Although he took after his father in appearance, his expression was gentler, lacking all hardness. Despite being nearly forty, he had held on to his boyish looks. When he smiled, her world seemed brighter, but when Ása saw him with the boys he coached at football, something seemed to break inside her.

She knew he wanted children. Not that he’d mentioned it, of course, but she knew. She was his mother, after all, and knew 30