7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

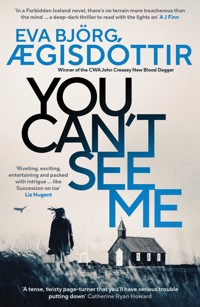

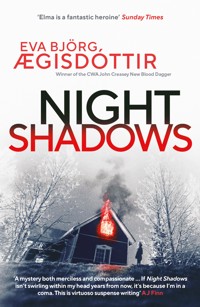

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Forbidden Iceland

- Sprache: Englisch

Icelandic detective Elma faces mortal danger as she investigates the death of a young man in a mysterious Akranes house fire, and a Dutch au pair's perfect placement turns deadly … The breathtaking third instalment in the award-winning Forbidden Iceland series. ***WINNER of the CWA John Creasey (New Blood) Dagger*** 'Her best, boldest work to date: a mystery both merciless and compassionate, subtly eerie yet flat-out frightening, featuring a detective as complicated as Jo Nesbø's Harry Hole. This is virtuoso suspense writing' A J Finn 'Chilling and addictive, with a completely unexpected twist … I loved it' Shari Lapena 'Another beautifully written novel from one of the rising stars of Nordic Noir' Victoria Selman _________________ The small community of Akranes is devastated when a young man dies in a mysterious house fire, and when Detective Elma and her colleagues from West Iceland CID discover the fire was arson, they become embroiled in an increasingly perplexing case involving multiple suspects. What's more, the dead man's final online search raises fears that they could be investigating not one murder, but two. A few months before the fire, a young Dutch woman takes a job as an au pair in Iceland, desperate to make a new life for herself after the death of her father. But the seemingly perfect family who employs her turns out to have problems of its own and she soon discovers she is running out of people to turn to. As the police begin to home in on the truth, Elma, already struggling to come to terms with a life-changing event, finds herself in mortal danger as it becomes clear that someone has secrets they'll do anything to hide… ___________________ 'A creepily compelling Icelandic mystery that had me hooked from page one. Night Shadows will make you want to sleep with the lights on' Heidi Amsinck 'I loved everything about this book: the characters, the setting, the storyline, an intricately woven cast … this book had me utterly gripped!' J M Hewitt 'With the third release in the Forbidden Iceland series, Eva Björg establishes herself as not just one of the brightest names in Icelandic crime fiction, but in crime fiction full stop. Night Shadows is an absolute must-read!' Nordic Watchlist 'One of the most compelling contemporary writers of crime fiction and psychological suspense' Duncan Beattie, Fiction from Afar Praise for the Forbidden Iceland series: 'Fans of Nordic Noir will love this' Ann Cleeves 'Elma is a fantastic heroine' Sunday Times 'Complex, gripping and moving' The Times 'An exciting and harrowing tale' Ragnar Jónasson 'Eerie and chilling. I loved every word!' Lesley Kara 'Not only a full-fat mystery, but also a chilling demonstration of how monsters are made' The Times 'Beautifully written, spine-tingling and disturbing … a thrilling new voice in Icelandic crime fiction' Yrsa Sigurðardóttir 'As chilling and atmospheric as an Icelandic winter' Lisa Gray 'An unsettling and exciting read with a couple of neat red herrings to throw the reader off the scent' NB Magazine 'Elma is a memorably complex character' Financial Times 'The twist comes out of the blue … enthralling' Tap The Line Magazine For fans of Ragnar Jonasson, Camilla Lackberg, Ruth Rendell, Gillian McAllister and Shari Lapena

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 491

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

The small community of Akranes is devastated when a young man dies in a mysterious house fire, and when Detective Elma and her colleagues from West Iceland CID discover the fire was arson, they become embroiled in an increasingly perplexing case involving multiple suspects. What’s more, the dead man’s final online search raises fears that they could be investigating not one murder, but two.

A few months before the fire, a young Dutch woman takes a job as an au pair in Iceland, desperate to make a new life for herself after the death of her father. But the seemingly perfect family who employs her turns out to have problems of its own and she soon discovers she is running out of people to turn to.

As the police begin to home in on the truth, Elma, already struggling to come to terms with a life-changing event, finds herself in mortal danger as it becomes clear that someone has secrets they’ll do anything to hide…

NIGHT SHADOWS

Eva Björg Ægisdóttir

Translated by Victoria Cribb

Contents

Pronunciation Guide

Icelandic has a couple of letters that don’t exist in other European languages and that are not always easy to replicate. The letter ð is generally replaced with a d in English, but we have decided to use the Icelandic letter to remain closer to the original names. Its sound is closest to the voiced th in English, as found in then and bathe.

The Icelandic letter þ is reproduced as th, as in Thorgeir, and is equivalent to an unvoiced th in English, as in thing or thump.

The letter r is generally rolled hard with the tongue against the roof of the mouth.

In pronouncing Icelandic personal and place names, the emphasis is always placed on the first syllable.

Names like Alexander, Begga and Elma, which are pronounced more or less as they would be in English, are not included on the list.

Aðalheiður – AATH-al-HAYTH-oor

Ævar – EYE-var

Akrafjall – AAK-ra-fyatl

Akranes – AA-kra-ness

Akureyri – AA-koor-ay-ree

Andri – AND-ree

Barónsstígur – BAA-rohns-STEE-goor

Birta – BIRR-ta

Borgarfjörður – BORK-ar-FYUR-thoor

Breiðholt – BRAYTH-holt

Brynhildur – BRIN-hild-oor

Dagný – DAAK-nee

Esja – ESS-ya

Finnur – FIN-noor

Fríða – FREE-tha

Fúsi – FOOS-see

Gerða – GYAIR-tha

Gígja – GYEE-ya

Grímur – GREE-moor

Guðlaug – GVOOTH-loig

Hannes Hreiðar Þorsteinsson – HAN-nes HRAY-thar THOR-stayns-son

Harpa – HAARR-pa

Hrafnkell – HRAPN-ketl

Hörður Höskuldsson – HUR-thoor HUSK-oolds-son

Húsafell – HOOSS-a-fetl

Hvalfjörður – KVAAL-fyurth-oor

Ína – EENA

Ísak – EES-sak

Jaðarsbakkar – JAA-thars-BAKK-ar

Jens – YENS

Jóel – YOH-ell

Jökull – YUR-kootl

Jón – YOEN

Júlía – YOO-lee-a

Kári – COW-rree

Katrín – KAA-treen

Laufey – LOIV-ay

Lise – LEESS-uh

Marinó – MAA-rin-oh

Mosfellsbær – MORS-fells-bye-r

Örnólfur – URD-nohl-voor

Óskar – OHSS-gar

Ragnar Snær Hafsteinsson – RAK-nar SNYE-r HAAF-stayns-son

Rúna – ROON-a

Sævar – SYE-vaar

Seyðisfjörður – SAY-this-FYUR-thoor

Skógahverfi – SKOH-a-KVAIR-vee

Snorri – SNORR-ee

Sonja – SON-ya

Stormur – STORM-oor

Tómas – TOH-mas

Unnar – OON-nar

Vilborg – VILL-borg

Villi – VIL-lee

PART ONE

The Night Before

Once the rain stopped, there was a risk someone would notice the smell. He made a phone call and said again that he wanted to move the body. It was making him increasingly anxious to think of it lying there, the decomposition advancing by the hour. The idea filled him with such anguish that he could barely sit still.

It was turning out to be incredibly difficult to dispose of a corpse. He couldn’t think of any way to carry it out to the car without being seen. The nights weren’t dark enough yet to provide sufficient cover. And even when he’d got it into the back, where could he go? Where was he supposed to bury it? He had never travelled much outside town and had no idea where to find a suitably out-of-the-way spot or even what the ground would be like. Was the soil deep enough, or would he hit rock? The last thing he wanted was for some farmer to dig up the body. Throwing it in the sea was one possibility, but there was always a risk it would wash up on a beach somewhere. He wasn’t familiar with the currents; had no idea whether the tide would be in or out right now.

Last night he had gone to check on it. In his drunken state he had been curious to observe the changes in the colour and texture of the skin. He had pulled back the covers, unwrapped the plastic and run a finger along the bare arm. There was an undeniable thrill in seeing a dead person. The sense of unreality was so overwhelming that it made him dizzy and sent the blood rushing to his fingers and toes. For a moment, thinking he was going to faint, he put his head between his knees. Then, when the spell had passed, he poured the rest of the vodka down his throat and turned his attention to the face. He prised open the mouth, inspecting the tongue and teeth, then carefully pushed up the eyelids. Underneath them, the eyes were dull and fixed, covered in a white film. It was then that the fact of death became too real for him and he stumbled away.

When he got back outside, he thought he was going to throw up, but instead he fell to his knees, overcome by a fit of weeping. He couldn’t stop picturing them, those unseeing eyes, staring back at him so emptily.

Saturday

Akranes’s wooden church was so tightly packed with mourners that the windows had started to steam up. Elma surreptitiously fanned her face with the hymn sheet. Yet although the building was full, the only sounds were the creaking of the narrow wooden pews and the occasional sniff or cough.

Hörður was sitting at the front with his family. Elma could see the back of his head, the grey-streaked hair and smooth shirt collar. He sat bolt upright, staring straight ahead, and didn’t look round when the doors opened and the people who’d entered walked down the aisle. Not even when his daughter laid her head on his shoulder. He sat so still it was as if nothing could stir him, or, perhaps, as if the slightest movement would shatter his hard-won composure.

Elma’s gaze moved from Hörður to the photo of Gígja on the service sheet. It was a recent picture but taken before the cancer had left its mark on her. She had gone downhill rapidly after her diagnosis. In a few short months they had watched this energetic woman growing ever weaker, the weight falling off her, until in the end she was bedbound, dependent on strong painkillers. Elma had last seen Gígja a month before she died. A few of them from the police station had gone to visit her, bearing pastries and a bunch of flowers.

Hörður too had lost so much weight that his trousers hung in loose folds around his thighs and his shirts were far too big for him. In the week since Gígja died, he hadn’t come near the police station.

Elma blinked back her tears and swallowed the lump in her throat. Sævar smiled sadly as the organist began to play, filling the little church with music, and the choir joined in, raising their voices in unearthly song. Only then did Elma notice Hörður’s head droop and his shoulders begin to shake.

The glass cabinet in the sitting room was a legacy from Laufey’s parents. She had never been able to get rid of the musty, old-cupboard odour that clung to everything they stored in it: the coffee set that had belonged to her parents, the Royal Copenhagen dish or the beautiful crystal glasses that had been a wedding present. Every time they wanted to use any of these items she had to wash them first to remove the smell.

It was the only job she had left to do. Everything else was ready. The potatoes were sitting on the kitchen counter, covered with aluminium foil; the meat had been browned and wouldn’t need much longer in the oven, and the dessert was waiting in the fridge – a large meringue cake filled with strawberries and chocolate-coated liquorice balls.

Unnar came into the kitchen, freshly shaven and wearing a fitted shirt. Unlike her, he’d had ample time to shower, shave and choose his clothes. She’d pulled on the same old dress when she found a minute, less than half an hour before the guests were due to arrive.

‘Champagne?’ Unnar asked, holding up the bottle.

‘No, thanks.’ Laufey untied her apron, trying not to be irritated by him. She didn’t want a quarrel when they were expecting their friends any minute.

‘Tired?’

‘Seriously, Unnar?’ Laufey asked. ‘Just so there are no arguments, you’re clearing up after dinner. I’m not lifting a finger.’

‘Sure, no problem.’ Unnar took the wineglasses into the sitting room and changed the music. While Laufey was toiling away in the kitchen, he’d had so much time on his hands, he’d been able to prepare a playlist for the evening ahead.

Laufey took a cloth and wiped away a smear that his damp fingers had left on one of the glasses. After a moment’s pause, she poured herself some champagne and took a sip, then another.

‘They must be here soon,’ she said, sitting down in an armchair.

Unnar shrugged. ‘You know what it’s like; no one turns up on the dot.’

‘No, I suppose not.’ She started and put down her glass.

‘Is everything OK?’

‘Yes, but I almost forgot to light the scented candle.’ Laufey got up and opened a drawer. She had bought an outrageously expensive candle at some luxury shop in Reykjavík, and if they didn’t use it now, when would they?

‘We can’t have that,’ she heard Unnar murmur sarcastically as she rummaged for a lighter.

Laufey took a deep breath and told herself that there was no point reacting. It wouldn’t do any good. She placed the candle on the hall table, lit all three wicks, and almost immediately the fragrance began to spread through the house. ‘Champagne Toast’ it said on the label. How appropriate, Laufey thought, and knocked back the rest of her glass.

As the evening wore on, people began to show signs of fading. Laufey sank lower in the sofa, losing the thread of the conversation. Villi started yawning, and shortly before midnight he and his wife Brynhildur got up and said goodbye. Óskar and Harpa, on the other hand, were nowhere near ready to throw in the towel. Harpa had downed eight glasses of champagne and was talking nineteen to the dozen. Óskar was no better; he’d taken over the playlist and was putting on songs that had been hits in their youth.

Laufey, feeling rather the worse for wear herself, went into the kitchen for a drink of water. The dining table was covered with dirty dishes and leftovers. She longed to tidy up, but that wouldn’t be fair: she had cooked and the clearing up was Unnar’s job. He wouldn’t get away with dodging it this time.

She folded a dishcloth, her gaze on the window.

It was raining outside, big, heavy drops falling vertically in the windless weather. She closed her eyes, breathing out slowly through her nose, and felt everything moving up and down inside her.

It was a long time since she had drunk this much, and she revelled in the sensation of being so relaxed and carefree. Her drowsiness had dissipated the instant she stood up, and she felt a sudden crazy urge to hit the town. But Akranes had no fun night clubs where you could dance until the early hours. They would have to make do with the sitting room.

Laufey got out another bottle of red wine and poured herself a glass. To hell with the dishes – she’d definitely make Unnar do them in the morning. She took a big mouthful and only then did she register the silence. The music had stopped, and she couldn’t even hear a word from Harpa.

Laufey went into the sitting room and saw the glasses on the table beside the cheeseboard.

‘Unnar?’ she said, but there was no answer.

It was as if they had all vanished into thin air.

Sunday

Ævar became aware of the fire when he looked out of the bathroom window and noticed a strange glow above the expensive property adjoining their back garden. At first he thought, sleepily, that the sun must have gone down behind the house in the middle of the night, but then he heard a piercing wail shattering the tranquillity and realised what was happening. He yanked up his briefs and made for the door, without stopping to wake Rósa or put on his coat.

The wet branches tore at his skin as he forced his way through the hedge dividing the two properties. The fire was at the front of the house, so Ævar made straight for the back door and tried the handle. When it wouldn’t open, he banged on the glass.

‘Hello!’ he called, pressing his forehead to the pane. ‘Is there anyone home?’

He expected to hear screams or see figures come running, but nothing happened. The house was home to a couple with two kids. In fact, they weren’t kids anymore; both must be around twenty, though they still lived with their parents.

Ævar was aware of his heart pounding under his thin vest but didn’t even register the cold. He wondered if he should break down the door. It looked easy enough in the movies, but he knew it was different in real life.

Instead, he ran round the corner of the house and saw to his dismay that there was a car parked in the drive. Somebody might well be home.

‘What’s going on?’

Ævar turned to see the man from the neighbouring house running over. What was his name again? Jón. Jens. Something like that.

‘Fire,’ Ævar gasped between panting breaths. ‘I can’t get in. I don’t know if anyone’s home. I…’

‘I’ll call the emergency number,’ said Jón or Jens, who’d had the presence of mind to pull on a coat and bring his phone with him. Ævar was barefoot and in his underwear, but this was no time to worry about such trivial things.

‘You ring, I’ll try the front door,’ he said and set off at a half-run. He winced with pain as the gravel cut into the soles of his feet.

The front door turned out to be locked as well and wouldn’t budge, despite all his efforts to force it.

A moment later there was a loud explosion. He saw that the glass in one of the windows had blown.

Ævar tried shouting again. ‘Is there anyone in there?’ he yelled into the blaze, but there was still no answer.

The heat and smoke were so bad that he couldn’t get any closer. He held his arm over his face, coughing, then heard the sirens and knew there was nothing more he could do.

Unnar woke up to find himself in bed, fully dressed. His white shirt was sticking to his body, and his suit trousers were unbuttoned to reveal his briefs. His mouth felt so parched that he worked his lips to try and summon up some saliva, then put his hands over his eyes to shield them from the dazzling sunlight that was streaming in through the window.

When he tried to sit up, pain knifed through his head, so he lay straight back down again and closed his eyes. After a while, he crawled out of bed and, with difficulty, made it to the bathroom, where the residue of the previous night’s excesses ended up in the toilet bowl.

Unnar was too old for this. Although he drank regularly, he didn’t normally get as wrecked as he had last night.

As he stood under the shower, he tried to remember what had happened. He recalled the dinner party and the first part of the evening. The bottles of Bollinger they’d drunk with the starter, the roast that had melted in the mouth after its long sous-vide cooking, the Hasselback potatoes. Everyone had praised the food, and afterwards they had polished off a bottle of ten-year-old malt that Villi had brought with him.

After that, though, the events of the evening grew hazy, and by the end of his shower Unnar was still no closer to remembering how he had come to be in bed with all his clothes on. The ominous feeling wouldn’t leave him as he was dressing, but the harder he tried to piece the evening together, the more it seemed to slip from his grasp.

His seven-year-old daughter, Anna, was practising gymnastics in the sitting room when he emerged.

She raised both arms, extended her leg, then bent over backwards and executed a full turn. Anyone would think she was double-jointed.

‘Wow,’ Unnar said, impressed. ‘What a clever girl I’ve got.’

Anna glowed with pride, then wrinkled her nose. ‘Daddy, your breath stinks.’

In the study he found Laufey seated at the computer, her glasses perched on her nose. The instant she became aware of him, she closed the window that had been open on the screen.

‘What, are you booking a flight?’ He thought he’d seen the logo of an airline.

Laufey turned. ‘Yes, actually,’ she said. ‘I still need to buy the tickets to Sweden.’

‘Still? But that’s only two weeks away.’

‘Yes, I know, I’m terribly behind.’ Laufey took off her glasses and rubbed her eyes, studying him as if she were seeing him properly for the first time in a very long while. ‘How are you feeling?’

‘Fine,’ Unnar lied.

‘You put away a hell of a lot last night.’

‘So did you.’

Laufey didn’t reply to that.

Unnar couldn’t actually remember whether Laufey had drunk a lot. He could hardly recall anything about her behaviour last night, except that she had chatted to the other wives while he and his friends were reminiscing about their schooldays. And she had given him the evil eye when he didn’t immediately clear away the dishes after supper.

He tried to read from her expression whether anything else had happened, but her face was inscrutable. She asked him if he wanted a coffee.

‘No,’ Unnar replied. ‘No, thanks.’

He watched as she went into the kitchen and poured some beans into the automatic coffee machine they had bought last Christmas.

His wife had once been beautiful, but these days she gave little thought to her appearance. A few years ago she’d had her hair cut short and started wearing glasses – God, how he hated those glasses. They made her look at least ten years older.

When they’d met she had been a fifteen-year-old with dreams of becoming a hairdresser. They had always been a bit wild, having sex wherever they wanted to: in an alleyway behind a club, in his parents’ bed, on a hotel balcony in Spain. Today she was forty-two, sat on Akranes town council, taught yoga and was studying for a degree of some sort. Whenever she spoke in public, her grating voice made him cringe. They rarely had sex and when they did it was over quickly.

Many of his colleagues’ wives looked much better and seemed to care far more about their appearance. But none of them could compare to Tommi’s new girlfriend, Helena. Tommi, who worked with him in the export department, had divorced his wife last year and his two kids were teenagers, so he rarely saw them. Helena had dark hair, a slim waist and big breasts. She’d just completed a degree in tourism studies and loved hiking. She was always dragging Tommi off into the mountains, and Unnar thought he seemed a changed man. But when he mentioned this, Tommi said it wasn’t the mountain hikes but all the sex that did it. Tommi had shown him a picture of Helena, bare-breasted, fast asleep in bed, then laughed uproariously.

Unnar was perfectly aware that his thoughts were superficial. After a long marriage, things like this shouldn’t matter to him, and yet they did. And it wasn’t just Laufey’s appearance that got on his nerves. She’d changed: she was no longer the fun, carefree, adventurous person she had once been.

Sometimes it felt as if they had nothing in common anymore apart from the children, but the day would come when the kids moved out. Then it would just be him and Laufey alone together, and he had no idea what they would say to each other.

‘What?’ Laufey asked, noticing him staring at her. She dunked half a biscuit into her mug, then stuffed it in her mouth.

‘Nothing,’ Unnar said.

‘Hangover that bad, is it?’

‘Are you sure you want to eat that biscuit?’ he retorted. ‘I thought you were on a diet.’

Laufey gave him a weary look and turned away.

A shrill, persistent sound penetrated her dreamless sleep. Elma buried her face in the pillow, not yet ready to wake up. There was a pause, then the sound started up again, and Elma realised it was the doorbell. She got out of bed, wrapped herself in her flannel dressing gown and went to the door. On the way, she caught sight of herself in the mirror and grimaced. Her hair, flattened by the pillow, clung to her face, her eyelids were swollen and the dark circles reached halfway down her cheeks.

Judging from Dagný’s expression, she hadn’t failed to notice the state her younger sister was in.

‘What happened?’ Dagný asked in concern, as she and her two little sons, Alexander and Jökull, came in. ‘Are you ill? Or … don’t tell me … were you out on the town last night?’

‘Have you only just woken up?’ Alexander asked, before Elma could answer. ‘But it’s like seriously late, man.’ He gaped at her in disbelief, stressing the ‘seriously’.

‘Yes, I know, but I was awake all night,’ Elma told him, ruffling his blond head. After the unusually fine Icelandic summer, his hair was bleached white and his skin was tanned golden brown. Elma raised her eyes to her sister. ‘Don’t worry, I wasn’t having fun – I just couldn’t sleep.’

‘I see. By the way, did you hear about the fire—?’ Dagný’s gaze suddenly darted past Elma, and she groaned. ‘Jökull, don’t open that drawer.’

Jökull, soon to be three, had made a beeline for the most interesting place in his aunt’s flat. The biscuit drawer was well within his reach, and he invariably opened it and helped himself when he came round.

‘Oh, Elma, can’t you move the biscuits somewhere else?’ Dagný said, sounding resigned as she watched Jökull dropping crumbs all over the kitchen floor.

‘I don’t want a biscuit,’ Alexander announced. ‘My coach says that if you want to be good at football, you should eat healthily.’

Elma raised her eyebrows. ‘Is that really something for a seven-year-old to worry about?’

‘Yes, of course, man,’ Alexander said. Recently his vocabulary had become peppered with new phrases and slang terms. The latest fad was to end all his sentences with ‘man’. ‘Aren’t you going to get dressed, Elma? The show’s about to begin, man.’

Elma glanced at the clock and saw that they’d be late if she didn’t get a move on. She’d promised to take her nephews to a play that was being performed at the local cinema.

‘Give me five minutes and I’ll be ready.’

‘It’ll take you more than five minutes,’ Dagný said, and now it was her turn to raise her eyebrows.

‘Here, Jökull, have another choccy biccy.’ Elma stroked the little boy’s head, then went into her bedroom and started dragging on her clothes. ‘What’s that you were saying about a fire?’ she called to her sister, but just then her mobile rang.

It was her boss, Hörður, head of West Iceland CID, on the other end, and it soon became clear that she wouldn’t be going to any plays that day.

The house was of an ultra-modern design, with large windows and a double garage. It had walls of varying heights and a steeply pitched roof, suggesting unusually high ceilings inside. A statement wall of cut stone added to the striking impression, reminding Elma of the places featured in the architecture and design magazines a friend of hers subscribed to. Surrounding the building was a large garden and a veranda that was evidently little used. There was no patio furniture, no barbecue nor any of the other clutter that was found in the gardens of the neighbouring houses. The fire damage was confined to the front of the building; the glass in one window had blown, and black streaks radiated out from the gaping hole.

They were in Akranes’s new Skógahverfi Estate. It was a quiet residential area, dominated by large villas, which were mainly occupied by families, including Elma’s friend who read the design magazines and had three kids. That summer they had sat out on her deck, drinking coffee. The surrounding gardens had been full of life in the good weather, with the sounds of children bouncing on trampolines or splashing in hot tubs.

On the way to the scene, Hörður had filled Elma in on what had happened. During the night a fire had broken out in one of the bedrooms, where a young man was sleeping. A neighbour had called the emergency number when he saw the blaze, but although the fire brigade had arrived promptly, they had been too late to save the boy.

‘His name was Marinó Finnsson, and he was twenty years old,’ Hörður said, as they got out of the car. ‘His parents were at a hotel in Borgarfjörður, and his twin sister was staying with her boyfriend, so he was alone at home. The fire seems to have started in his room.’

‘Is that it?’ Elma asked, pointing to the broken window.

‘Yes, that’s his room,’ Hörður said. ‘The forensic team’s in there now. I spoke to them earlier this morning and they’re fairly sure it’s arson. When the fire brigade turned up, Marinó was still in bed.’

Perhaps it was her imagination, but the area seemed unusually quiet to Elma. Looking around, she saw a few curious eyes watching them. On one of the houses, the Icelandic flag was flying at half-mast.

‘Was there no smoke alarm in the house?’ she asked.

‘Yes, there was. It woke the neighbours.’

‘But Marinó didn’t wake up?’

‘No,’ Hörður said, ‘apparently not. There was an alarm in his room that must have gone off almost immediately. In normal circumstances he would have had time to get out, or at least you’d think so. Mind you, when I spoke to the lead firefighter, he told me that it was only a matter of seconds sometimes.’

‘Could they tell straight away that it was arson?’

‘They suspected it pretty quickly,’ Hörður said, opening the front door of the house. ‘But, like I said, the fire originated in Marinó’s room, which is strange if we’re talking about arson. The front door was locked, so I find it unlikely that anyone could have entered uninvited. Unless the person in question locked the door on their way out.’ Hörður bent a little closer to Elma and added in an undertone: ‘But of course it’s possible that the victim started the fire himself.’

‘I suppose so,’ Elma said, after a pause. ‘Or that the person who started the fire had access to the house.’

Finnur couldn’t stand his mother’s flat. He couldn’t stand the red velvet sofa in the sitting room, the painting of the little girl by the stream, the blue-checked cover on the double bed. A faint smell of cigarette smoke clung to all the furnishings, even though his mother had quit smoking around the time his father succumbed to lung cancer.

An oppressive silence had hung over the house when he was growing up, in spite of the constant blare of the television. His parents used to spend their days slumped in front of it. Both had been registered disabled, subsisting on a low income, yet somehow there had always been enough money for booze and fags. Finnur had learnt early on that the only rules were: don’t touch Mum’s drink. And don’t touch Dad’s drink. Apart from that he could stay out to all hours, as long as he didn’t disturb his parents in the morning, when they would invariably be hung-over. They were never mean to him, not directly, but if anything their indifference was worse.

While still young, Finnur had promised himself that he would escape this miserable existence as soon as he could and would never turn into his parents. He had kept his word. He was now fifty-five, he’d been sober since he was nineteen and he was very comfortably off financially.

As he watched his bank balance growing over the years, he’d felt as if he was simultaneously growing in stature. He’d felt both proud and powerful; like one of life’s winners.

But what had he actually won? he asked himself now, studying the photograph in his hands. Where was the victory?

The photo was of a five-year-old Marinó holding a kitten the twins had been given one Christmas. Although Marinó had been pestering them for months to have a cat, he had grown nervous the moment the animal was put into his arms, and his fear showed in his expression. His eyes were stretched wide, his body tense, as if he were expecting the cat to shoot out its claws and scratch him. Finnur ran a finger over the picture, aching to touch his son one last time.

Since hearing of Marinó’s death, he’d felt as if he were sinking into a bottomless abyss. It couldn’t be true that his son no longer existed. How could the world go on without Marinó?

There was a stabbing pain in his chest. For a moment he felt crushed by his grief, but an instant later rage flared up inside him.

It wasn’t an accident. Someone had deliberately done this to his son, and Finnur thought he knew who. He opened his laptop, found the old emails and reread the angry messages. They hadn’t really got to him at the time; other people’s problems had seemed irrelevant. As far as he was concerned, it had just been some pathetic, sick individual, who would never dare to put their threats into action. But he saw things differently now.

He typed the sender’s name into the search engine and saved the address. Then he closed his laptop and picked up the photo again, losing himself in memories of a past he would never get back.

‘I don’t understand it,’ Marinó’s mother, Gerða, said, her hands trembling as she put down the glass of water. ‘I don’t understand what happened. It must have been the wiring. The light in Marinó’s room was always flickering and I told—’

‘No,’ Hörður intervened hurriedly. ‘There’s nothing to suggest the fire was caused by the wiring.’

Gerða closed her eyes and drew a long, shaky breath. Elma saw how much it was costing her not to break down.

They were sitting in a flat belonging to Finnur’s elderly mother, Agnes. When Agnes opened the door to Elma and Hörður, her movements had been slow and her face frozen. Of course, the circumstances were nothing to smile about, but Elma had got the impression that Agnes wouldn’t have smiled regardless of the occasion. Without saying a word, the old woman had pointed to the sitting room, then disappeared into another room herself, closing the door behind her.

‘The forensics team is still examining the scene,’ Hörður said, ‘but I’m afraid it’s fairly clear that it was arson.’

‘But that’s impossible,’ Gerða said, stunned. ‘Who…?’

‘I’m afraid we don’t yet know who was responsible,’ Hörður said. ‘But we’ve found traces of a flammable substance, and the behaviour of the fire also points to arson. That’s to say, it spread far more quickly than it would have done naturally.’

Silence descended on the room, then the clock struck the hour, and they all looked up. All except Finnur. The short, delicately made man, sitting so rigidly on the sofa, appeared to be miles away. His thick, bushy eyebrows gave him a rather dour expression.

‘Where were you staying on Saturday night?’ Elma asked, breaking the silence.

‘We were at a hotel in Borgarfjörður,’ Gerða replied, referring to the countryside around the large fjord some thirty kilometres north of Akranes.

‘What’s the name of the hotel?’

‘Hótel Húsafell. We got there at five on Friday afternoon and stayed for two nights. We went to the, er … to the Krauma nature baths and had our meals at the hotel restaurant.’

‘Do you remember when you last heard from Marinó?’ Elma asked.

‘He rang me just after midday on Saturday, saying he couldn’t find his swimming trunks. He was going to the gym and wanted to use the hot tub afterwards.’

‘Did he seem at all different from usual?’

‘No,’ Gerða said. ‘No, he didn’t.’

‘What about in the last few days or weeks?’

‘No,’ Finnur said suddenly. ‘No different.’

‘Actually, he was a bit distracted, Finnur,’ Gerða said quietly. ‘Now I come to think of it, he wasn’t home much last week. He went out in the evenings and got back late.’

‘Was that unusual?’

‘Well, it happened sometimes, but not that often.’

‘Did you get the feeling something was bothering him?’

‘To be honest, I didn’t even think about it,’ Gerða said. ‘But now that you mention it…’

‘It was nothing.’ Finnur sounded almost angry. ‘There was nothing bothering him; nothing wrong with him. He was exactly like his usual self. Exactly…’ His voice cracked and he turned his face away.

‘Can you think of anyone who might have wanted to harm Marinó?’ Elma asked. ‘Had he fallen out with someone recently?’

‘No,’ Gerða answered quickly. She sniffed, fighting back her tears. ‘Marinó wasn’t like that; no one had it in for him. He was a good student, he had a nice group of friends and lived a very normal life. He … he was ambitious, he had opinions about politics, he played the saxophone and wanted to work in IT. And he was interested in history and Greek philosophy too – he read all those books by Plato and Aristotle right the way through. He wasn’t in any kind of trouble.’

‘Marinó had just started a degree in computer studies at the University of Iceland,’ Finnur said, having regained control of his voice. ‘As my wife says, he was never in any kind of trouble, if that’s what you’re trying to imply. He wasn’t mixed up in bad company; he didn’t take drugs or anything like that.’

‘Who were his friends?’

‘Marinó’s had the same group of friends since he was at school,’ Gerða said, wiping a tear from her cheek with a quick movement. ‘Ísak, Andri and Fríða – Marinó’s twin sister. Oh, and her friend, Sonja.’

Elma asked for their full names and noted them down.

‘Who has access to your house?’ she asked next.

‘Only us.’ Gerða glanced at her husband.

‘Yes, only our family,’ Finnur confirmed. ‘Why do you ask?’

‘The door was locked when the fire brigade reached the scene,’ Elma said, ‘but the fire was started inside the house.’

‘I don’t understand,’ Gerða said. ‘What does that mean?’

‘We’re wondering if Marinó could have forgotten to lock the door and the person who started the fire locked it behind them on their way out,’ Elma said. The idea didn’t sound very convincing to her, but it was all she could come up with. If someone from outside the family had started the fire, then logically they must have got in somehow. She doubted that Marinó had let them in voluntarily, if he had been in bed.

‘No, that can’t be right,’ Finnur said.

‘That he’d have left it unlocked?’

‘No, not that. The door doesn’t lock automatically – you have to use a key.’

‘I see.’ Elma shifted in her seat. ‘So, someone must have locked it from outside, using a key.’

‘But…’ Gerða moved forwards to perch on the edge of the sofa. ‘But we’re the only ones with keys.’

‘Are you absolutely sure about that?’ Elma asked.

‘Yes, only us and the twins,’ Gerða said. ‘Oh, and Agnes, Finnur’s mother.’

Hörður cleared his throat, and Elma could tell he was uncomfortable about asking the next question. ‘Was Marinó on any drugs?’

‘Drugs?’ Finnur repeated indignantly. ‘No, he wasn’t.’

‘Were there any drugs in the house?’

‘What … why are you asking that?’ Gerða sounded bewildered.

‘I was just wondering if Marinó could have unwittingly taken some medication,’ Hörður said. ‘Accidentally taken some pills, for example, under the impression that they were painkillers.’

‘I don’t know what you’re insinuating,’ Finnur said angrily, ‘but, I told you, Marinó didn’t do drugs. He didn’t have any problems of that kind.’

‘Do you think there’s any chance he could have started the fire himself?’ Hörður asked warily.

‘That’s it. I’m not putting up with any more of this.’ Finnur sprang to his feet, tight-lipped.

Hörður added hastily: ‘I ask, because your son doesn’t seem to have woken up when the smoke alarm went off, although it was loud enough to disturb the neighbours. As I said, Marinó was still lying in bed when the fire brigade arrived and didn’t seem to have made any attempt to get up.’

The conversation with Marinó’s parents had taken its toll. Elma always dreaded having to ask next of kin probing personal questions, but it couldn’t be avoided. The most uncomfortable questions were often the most important, but people reacted very differently to them. Finnur had been seething with rage by the end. He had stalked off into another room without a word, leaving it to his wife, Gerða, to escort them to the door.

It was understandable that Marinó’s parents had a hard time believing someone could have entered his room in the middle of the night, started a fire then left again, locking the door behind them – all without waking Marinó. Yet Elma wasn’t about to rule out the possibility; it was vital to keep an open mind.

Gerða told them that the only spare keys to the house were hidden under a stone by the wall. So there was a chance, however slim, that someone could have found the key and let themselves in. A neighbour, perhaps, who knew where it was kept. Elma was also considering the possibility that Marinó had a girlfriend his parents weren’t aware of. It was the only thing she could think of to explain why he would have let someone in, then been found lying in bed.

‘Which stone do you think it is?’ Sævar asked.

‘Gerða said it was quite a big one, under the window,’ Elma told him.

Following the visit to Marinó’s parents, she had picked up her colleague, Sævar, from the police station. Hörður had stayed behind in his office, saying he would go over the press release before heading home. She couldn’t understand why he was at work at all, given that it was only a week since Gígja had died. When she had spoken to him the previous week, he had talked about taking several months off, but this morning, the day after the funeral, he had turned up at the station. Elma longed to tell him to go easy on himself but didn’t know how to put it tactfully.

‘They’re all pretty big,’ Sævar pointed out.

He was right. A number of large stones had been lined up, decoratively, along the house wall.

‘It’s not a bad hiding place,’ Elma remarked. ‘Most people put their keys in a flower pot or in the light fitting over the door.’

When she was growing up, she would retrieve the spare key from the flower pot by the front door – on the rare occasions it had been necessary. Usually the house had been left unlocked, regardless of whether anyone was home.

Elma pulled on a pair of latex gloves and turned over the largest stone below the window. Seeing nothing underneath, she moved on to the next.

‘There are no keys here,’ she said at last. Straightening up, she surveyed their surroundings.

There was an unusual amount of traffic in the street: vehicles were slowing down as they passed, presumably to get an eyeful of the damage caused by the fire. News of last night’s incident had spread fast, and it was all over the national media today.

When Elma drove through the town earlier, she had noticed a number of flags flying at half-mast. Although she could think of plenty of disadvantages to growing up in a small community like Akranes, there were advantages too, and the feeling of solidarity was probably one of the biggest. Whenever anything bad happened, it brought the locals together.

Elma tried not to dwell on thoughts of Marinó’s family and friends. She and Sævar had to focus on solving the case, and their first step must be to talk to the neighbours. With any luck, one of them might have witnessed something that could explain the terrible tragedy.

After they rang the bell, there was a short interval before the door opened. The man who came out was around their age – thirty-something – with thinning hair and glasses. They followed him into the kitchen, where a woman was sitting with her hair pulled back in a loose bun.

‘I gather it was you who called the emergency number last night?’ Elma said.

‘Yes,’ the woman replied, looking at the man. ‘Jens rang.’

‘That’s right,’ Jens said. ‘I couldn’t sleep and I was here in the kitchen when I heard the alarm go off. I went over to the window and saw smoke coming from Gerða and Finnur’s house, so I ran outside and saw another neighbour, Ævar, banging on their door. That’s when I called the emergency number. If I’d known the son was in the house, I’d have tried to do more to…’

‘But we heard the fire brigade coming almost straight away,’ the woman said, as if to comfort him. ‘Jens had hardly hung up before we heard the siren.’

‘Did either of you notice anyone near the house when you looked outside?’

‘Near the house? No, I … Jens?’

Jens frowned. ‘No, I didn’t see anyone. But then I wouldn’t have been able to see even if someone had come out of their front door.’

Elma glanced out of the window where Jens was pointing and saw that he was right. The garage jutted out further towards the street, blocking the view of the entrance to Gerða and Finnur’s house.

Jens had cottoned on immediately. ‘You think it was arson – I saw on the news.’

‘We’re looking into all the possibilities,’ Sævar replied, though Jens’s comment hadn’t been a question. ‘The origin of the fire’s not entirely clear yet.’

Apparently unconvinced that Sævar was telling them the truth, the couple waited, presumably hoping their silence might elicit more information. But then a voice called ‘finished’ from another part of the house, and the woman excused herself and left the room.

‘Do you know Gerða and Finnur well?’ Elma asked.

‘Not exactly well but, you know, we’re neighbours, so we have to talk to each other occasionally.’ Jens’s lips twitched ironically. ‘I noticed that they were off somewhere for the weekend. Finnur put a suitcase in the boot of their car on Friday afternoon. There’s been quite a lot going on there over the last couple of days.’

‘Really?’

‘Yes, or mainly on Friday.’

‘Could you be more specific?’

‘Oh, you know: the kids obviously took advantage of their parents’ absence to throw a party. I’m not really complaining but there was quite a lot of noise on Friday night. It wasn’t us who called the police, though.’

‘Did someone call the police?’

‘Yes, apparently there was a spot of bother, but the police came round and put a stop to it. I didn’t see anything myself, but I heard about it from Rósa and Ævar, who live opposite. They were the ones who called the police.’

‘I’m so sorry, I don’t know what to say. Poor Finnur, poor Gerða.’ Rósa looked out of her kitchen window with a heavy sigh. ‘I can hardly believe Marinó’s dead. He was such a nice boy.’

Rósa and Ævar lived in the property backing onto Finnur and Gerða’s place, their gardens separated by a thick hedge.

‘I hear you were the first person to notice the fire,’ Elma said, turning to address Ævar.

‘Yes.’ Ævar stared across the table at them, his brows heavy. ‘But it’s not like I was any use.’

‘Could you tell us what happened?’

Ævar cleared his throat then briefly related how he had seen a strange glow when he woke up in the middle of the night. He hadn’t realised what was happening at first, then he had heard the smoke alarm and run outside.

‘I tried to get in but…’ Ævar lowered his eyes, and Rósa put a hand on his arm. Her fingers were puffy, her wedding ring far too tight.

‘It wouldn’t have made any difference,’ Elma assured him. ‘The fire spread so fast that you would only have been putting your own life in danger if you’d gone inside.’

‘They said on the news that it might have been arson,’ Rósa remarked, after a little silence.

‘There are various indications that it might,’ Elma said. ‘That’s why we wanted to check if you’d been aware of any unusual activity around the house.’

‘No, I didn’t see anything,’ Ævar said. ‘But then all my attention was focused on the fire.’

‘Ævar ran out in his underwear,’ Rósa said. ‘I doubt he was thinking about anything except getting into the house.’

‘What about you?’ Elma asked Rósa.

‘No, but…’ Rósa paused to think. ‘But I did hear a car earlier last night, and I also heard people talking outside.’

Ævar snorted. ‘You’re imagining things. The other day you were sure you heard a baby crying in the middle of the night.’

‘But I did. I’m sure I did.’

Ævar shook his head and addressed Sævar and Elma. ‘There are no babies in any of the neighbouring houses; not a single one.’

‘What nonsense,’ Rósa said. ‘Of course there’s a baby in the street.’

‘That little boy lives three doors down,’ Ævar said. ‘Do you really think you can hear him through three houses? You can’t even hear when I call you from the other room.’

‘Selective deafness can come in handy sometimes.’ Rósa smiled at Sævar and Elma. ‘But I’m absolutely sure I heard a car.’

‘Did you see the car or the people who were talking?’

‘No, it was around one in the morning. I was lying in bed and only woke up because Ævar was tossing and turning.’

‘We heard there was quite a party there on Friday night?’ Elma said.

‘Oh. Yes,’ Rósa said. ‘But it wasn’t me who rang the police. I don’t mind kids having a bit of fun. You’re only young once.’

‘The music was far too loud,’ Ævar protested. ‘It was impossible to sleep for the racket. There are young children…’

‘Aha!’ Rósa exclaimed. ‘So now you’re admitting there are babies in the street?’

‘Young children, not babies,’ Ævar corrected her.

‘We hear things got a bit rowdy,’ Elma said. She’d already been in touch with her uniformed colleagues who had attended the callout and put a stop to the party. According to them, the kids had been drunk and playing loud music but there had been no sign of a fight.

‘Well … I heard smashing sounds and people having a row,’ Ævar said.

‘Again?’ Rósa asked. ‘I heard them quarrelling the other day.’

‘Who did you hear quarrelling?’ Elma asked, since Rósa didn’t seem to be talking about the party.

‘Oh, the twins,’ Rósa said. ‘Fríða and Marinó.’

The roast lamb had been taken out of the oven by the time Elma made it to her parents’ house. Her father was laying the table, her mother standing at the stove.

‘How’s Sævar?’ Aðalheiður asked, the moment Elma walked in. Then she picked up a carton of milk and poured a thin stream into the butter and flour in the saucepan, deftly stirring all the while.

‘Fine, I think. Why don’t you ask him yourself?’ Elma said, pinching a slice of cucumber from the salad bowl.

‘I would if he was here.’

Ever since Elma and Sævar had gone to Tenerife together last Christmas, her mother had been regularly asking after him. To her mind, going abroad together must mean they were more than just friends.

Elma and Sævar had decided at the last minute to jump on a plane to the Canary Islands for the holidays. They were both at a similar stage in their lives – single and childless – and somehow neither had felt in the Christmas spirit; their yearning for sun, sand and sea had been much stronger.

Sævar had lost his parents many years before, and his brother, Maggi, who used to live in a group home for the disabled in Akranes, now had his own flat. Maggi had wanted to spend Christmas with his new girlfriend and her family, which meant Sævar had been faced with the prospect of a lonely festive season. His only other option – an invitation to stay with an aunt up north in Akureyri – hadn’t tempted him, so he’d been more than up for it when Elma had suggested, half joking, that they go on a beach holiday together.

After supper, Elma and her father cleared up while her mother settled in front of the television with her knitting needles.

‘Mum,’ Elma said, when she finally sat down beside her. ‘What do you know about Finnur and Gerða?’

Her mother worked for Akranes council and had done ever since Elma was a little girl, and she could be relied on to know everything about everyone. This case turned out to be no exception as Aðalheiður immediately launched into a detailed account of the family, without slowing the pace of her knitting.

‘You mean the parents of Marinó, who died in the fire last night? God, that was terrible. Marinó was such a promising boy. A talented saxophone player, I’m told.’ Aðalheiður paused to glance at her knitting pattern, then carried on. ‘Let’s see. Marinó had a twin sister called Fríða. They’ve had a bit of bother with her since she got involved with a much older boyfriend. I hear they recently pranged their car…’ The knitting needles clicked rhythmically as Aðalheiður talked. By the time she’d finished, Elma had a pretty good picture of the family, certainly far more complete than anything she could have gleaned from the internet. Her mother’s nosiness came in extremely useful at times.

When Elma got home later that evening, she ran herself a bath, thinking over what her mother had said. Propping her toes on the edge of the tub, she reclined her head and wallowed in the soothing warmth.

Finnur was a local, born in Akranes, while Gerða came from the mountainous Dalir district, further up the west coast, but the couple had lived in the capital, Reykjavík, for most of their married life. In typical Icelandic fashion, Aðalheiður had digressed onto the subject of Finnur’s family tree, mentioning the names of his parents and even his grandparents. Since Elma hadn’t heard of any of them, most of what her mother said on the subject had gone in one ear and out the other. But she had sat up when Aðalheiður explained that Finnur had made a killing out of buying up properties from the Housing Financing Fund after the 2008 financial crisis; in other words, properties that had been repossessed after their owners failed to keep up with their mortgage payments. Finnur had bought them cheap and later sold them on for a steep profit. Many people had looked askance at the couple as a result and muttered about unethical behaviour, while others had simply regretted their failure to spot this chance of making a quick buck themselves. Not that it would have been possible for just anyone to buy up the flats; for that, you would have needed Finnur’s connections.

At the time the banks went under, he had been working for an investment fund in Reykjavík. Later, when many people found themselves saddled with loans they couldn’t pay back, he had purchased a plot of land in Akranes and built a large detached villa. The house was so swanky that it wasn’t uncommon to see cars slowing down as they drove past, their owners gawping out of the windows. Some didn’t even try to hide their curiosity and stopped outside for a closer look.

While the house was under construction, there had been a lot of gossip among the townspeople about the family who were planning to move there. They had pictured a bunch of snobs, as Elma’s mother put it, but, in the event, it turned out Finnur and Gerða were not into showing off their wealth. The couple were in their fifties – they’d had the twins fairly late – and with the exception of their ostentatious house, they kept a low profile in Akranes society. Both were short and slight. They rarely used the car that was parked in the double garage, preferring instead to get about by bike or on foot. Their friendly, unaffected manners soon put a stop to the gossip, and the town gradually lost interest in them.

The twins were also very ordinary kids, who didn’t make much of an impression at school. Fríða and Marinó had both gone to Grundi School, Elma’s alma mater, but had been in different classes.

Elma still hadn’t met Fríða, who had been staying with her boyfriend the night her brother died. Finnur and Gerða had begged the police to give their daughter a little time, as she was so distressed, but sooner or later Elma would have to talk to her. If anyone had known Marinó well, it was surely his twin sister.

Elma washed her face in the hot bathwater, rubbing the mascara from her eyelashes.

Marinó’s parents’ grief had really got to her. She couldn’t imagine what it was like to lose a child. It was bad enough thinking what it would be like if anything ever happened to her nephews, Alexander and Jökull. Of course she shouldn’t let her imagination run away with her like this, but it was hard not to. She found it difficult to avoid empathising with other people’s pain and entering into their grief.

Elma had sometimes met parents who had lost children many years previously, through accidents or other causes, and it always seemed as if something had been taken away from them. As if their faces had been permanently marked by their loss.

She slid down until her head was submerged, then sat up again and wrung out her hair before heaving herself to her feet.

Today was one month since she had realised that all was not as it should be, and three weeks and five days since she had received confirmation of the fact. She had about seven months left until her whole world would be changed beyond recognition.

By Sunday evening Unnar couldn’t stand it any longer and rang Villi.

‘What the hell happened last night?’ he asked. ‘I can’t remember a bloody thing.’

Villi laughed so hard that he choked on his energy drink.

‘Were you that drunk?’ he asked, when he had finally caught his breath.

Unnar wanted to scream. He wasn’t used to losing his cool like this; as a rule, he liked to be in control. ‘Come on. Did anything happen?’

‘We finished my whisky.’

‘And?’

‘And?’ Villi coughed into the phone, and Unnar pictured his beer gut wobbling up and down. The keto diet he’d been following for the last year didn’t seem to have done any good. If anything, Villi had put on weight from all the bacon and cheese he had been putting away. ‘You started playing U2 and Prince and then I knew it was time to leave.’

Unnar bent forwards over his desk and rubbed his temple. ‘Was Laufey … How was Laufey?’

‘What do you mean?’

‘Was she drunk too?’

‘Well…’ There was a pause at the other end. ‘She was probably the most sober of all of us. Brynhildur and I were wrecked next day. Brynhildur had invited her parents to lunch and we had to cancel, claiming I had a stomach bug. And obviously I don’t know what happened after we left you.’

‘Did you leave that early?’

‘Not that early … We went home at midnight, leaving you two with Óskar and Harpa. The last thing I remember was you and Harpa involved in some big discussion, and Óskar taking over the music. I have to say, he has better taste than you.’

Unnar hung up, racking his brains to remember the discussion, the music, anything. But all he could recall was the smell of damp grass and the feel of his wet shirt clinging to his back.

Monday

‘Good news.’

Elma started as Begga burst into the kitchen with her usual noisy bustle. Begga wasn’t a detective like Elma but a uniformed officer who worked shifts. The two women had been friends ever since Elma joined the Akranes police, and she was always glad when Begga had a day shift during the week. As a member of CID, Elma worked conventional hours, and they didn’t always coincide with Begga’s.