8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

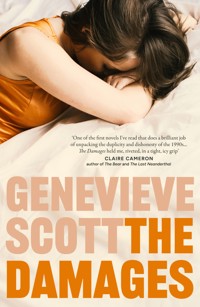

- Herausgeber: Verve Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

What I remember best about that week in January is trying to keep track of all the lies I told...

1998. Ontario has been hit by a days-long, life-endangering ice storm, and on Regis University campus, with classes cancelled, the students are partying. In the midst of it all, eighteen-year-old Ros's roommate Megan goes missing. As a panicked search ensues, Ros is blamed for not keeping a closer eye on Megan, and the incident casts a shadow over the next two decades of her life.

2020. Ros's former partner, Lukas, the father of her eleven-year-old son, is accused of a sexual assault. The accusation brings new details of an old story to light, forcing Ros to revisit a dark moment from her past. Ros must take a hard look not only at the father of her child, but also at her own mistakes, her own trauma, and at the supposedly liberal period she grew up in.

PRAISE FOR THE DAMAGES

'A thriller with a narrator you won't be able to get out of your head' - Toronto Star

'Scott opens wide the blurred lines of the Me Too movement... A propelling and thought provoking book that you just can't put down' - The Suburban

'A thought-provoking examination of truth, trauma, and memory, briskly and attentively presenting readers with a vivid portrait of one woman's complicated experiences. A compelling character study that tackles intriguing moral questions' - Kirkus

'This is one of the first novels I've read that does a brilliant job of unpacking the duplicity and dishonesty of the 1990s. An intelligent and intense read about how power structures are passed on - The Damages held me, riveted, in a tight, icy grip' - Claire Cameron, author of The Bear

'Scott is a sophisticated writer, and The Damages is a sharp, multi-layered story about truth, lies, history and memory' - Sarah Selecky, author of Radiant Shimmering Light

'A probing, courageous work – a dance along the tightropes of memory, justice and love. It explodes the myth of the innocent bystander and ultimately celebrates the lifelong moral challenge of learning who you really are' - Sarah Henstra, author of The Red Word

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

PRAISE FOR THE DAMAGES

‘In the 1990s, women were going to university and joining the workforce in record numbers. Why, then, do many of us have conflicted feelings when looking back? This is one of the first novels I’ve read that does a brilliant job of unpacking the duplicity and dishonesty of the era. An intelligent and intense read about how power structures are passed on – The Damages held me, riveted, in a tight,icy grip’ – Claire Cameron, author of The Bear

‘The Damages is a probing, courageous work – a dance along the tightropes of memory, justice and love. It explodes the myth of the innocent bystander and ultimately celebrates the lifelong moral challenge of learning who you really are’ – Sarah Henstra, author of The Red Word, winner of the Governor General’s Literary Award for Fiction

‘The Damages is an eerily sharp depiction of being self-conscious, self-obsessed, and eighteen in the late nineties, and just how painful it can be to face the past and question why one makes the choices they do when they’re young. Packed with insecurity, embarrassment, jealousy, and shame, each page made me anxious in the best possible way. Heart pounding, I couldn’t stop reading!’ – Cedar Bowers, Scotiabank Giller Prize-longlisted author of Astra

‘There is a skillful irony in a character so courageously honest about her lies. Genevieve Scott offers a view inside of a complicated woman from young adulthood to middle age, in refreshing and deceptively clean prose. The Damages takes a critical look at truth and perspective in a (post-) #MeToo era, calling into question the ways our personal truths are shaped by our pasts’ – Fawn Parker, Scotiabank Giller Prize–longlisted author of What We Both Know

‘The Damages led me into a maze with a thread – and then just never let me go. This story builds with thrilling intensity through moral knots and human dilemmas, led by a brilliantly complex protagonist as she navigates her way through betrayal, guilt and culpability’ – Charlotte Gill, author of Almost Brown

‘The Damages is the most honest novel I’ve read in a long time. A propulsive story about the complexities of trust, the cruelties in relationships, and the space between meaning well and doing good. Genevieve Scott is a fresh, brilliant voice in fiction’ – Leah Mol, author of Sharp Edges

‘Genevieve Scott is a sophisticated writer, and The Damages is a sharp, multi-layered story about truth, lies, history and memory. I stayed up late to finish it! I was not disappointed: this is a complex and satisfying novel’ – Sarah Selecky, author of Radiant Shimmering Light

For my mother

This novel contains discussion of sexual assault that may be sensitive to some readers.

PROLOGUE

Spring 2020

What I remember best about that week in January is trying to keep track of all the lies I told. Still, they want to hear from me.

Elaine Ng called it a conversation. We could meet whenever it suited me. Nothing to bring along, just my memory.

I haven’t met Elaine Ng, but I have studied her photo on the Burton Jafari LLP website. She is attractive, a year younger than me, if I’ve calculated her age correctly from LinkedIn. Two years ago, a Canadian legal magazine named her a ‘Top 40 under 40.’ I’m sure her personal and professional choices have been, on balance, more impressive than mine, which is the main way I size up women now. At one time, the time period she wants to discuss, I considered only prettiness, thinness, and some ever-evolving coolness factor, indexed from aesthetic choices like cut of jeans and hairstyle (though even by this standard, Ms Ng scores high). Ms Ng is probably good at what she does, but I don’t understand this whole system, her system, that puts so much stock in the reliability of memories.

Back when I lived with Lukas, he said he didn’t need to remember things like our dry cleaner’s name or our friends’ food sensitivities because my memory was a spiderweb, nabbing every detail. At dinner parties, I was proud to supply whatever got lost at the tip of a storyteller’s tongue – the name of a child actor, the year of the Albertville Olympics, the author of a book I’d never read. Early in our relationship, Lukas brought me to lunch with his agent, and years later, he marvelled at what I could still recall about the evening: the Weimaraner she waved at through the window, her tendency to repeat the phrase ‘Let’s face it,’ the fleck of taramasalata on the sleeve of her white caftan. I liked being the person who could turn up scraps like these – it was a party trick. It was also, I see now, a distraction. A way to seem clever and observant while avoiding anything of substance. I don’t remember much of what the agent said about Lukas’s book that night or why they stopped working together several months later. My memory may nab more details than most, but these details don’t form a complete picture; more often, they obscure what’s there.

I could describe to Ms Ng, for instance, the shirt Megan wore to the bar on the night she went missing. It was borrowed from Sue, white with a ruffle over the chest. I once read a teen magazine article on swimwear that described flattering bathing suits for various body types: ‘Not much on top? Reach for a ruffle!’ Megan tried it on at the full-length mirror on Sue’s closet door. From the way she bit her lip, I could tell that she liked how it looked. But I don’t think this is the sort of detail Ms Ng is seeking.

I searched Regis University online and found a news clip from this past March, a segment on students who were refusing to social distance despite the covid outbreak in the town of Creighton, Ontario. It was the first time I’d seen the campus in over two decades. The kids were crowded in front of a reporter’s microphone, jackets open, glittery hats jauntily askew, green beer sloshing in frosted glass mugs. One pretty girl narrowed her eyes at the camera. ‘Are we not allowed to enjoy our lives?’

They sounded so dumb. Were we that dumb?

If that week in January had happened even a decade later than it did, this conversation would be easier. I would have photographs, videos, all kinds of documentation. There would be hashtags: #Pray4Creighton, #CreightonStrong. But we didn’t have cellphones or social media in 1998. I didn’t take pictures, hardly used email. Ballpark is the best I can do for Ms Ng, if I talk to her at all.

The few things that I’m certain of are the things that everybody knows. Megan Main, my roommate, went missing from Alice Cole Hall on January 9, 1998. Though there were 250 people sleeping in a dorm built for 115 that night, no one saw her leave. It was in the middle of the biggest ice storm in Creighton’s history.

On the first night, the storm was magical. Our campus was like the atrium of a shopping mall at Christmas: trees dripping with tinsel-fine icicles, rime-crusted windows, sparkles of moisture under the streetlamps. But freezing rain fell for days. Thick layers of ice accumulated on trees, windshields, hydro poles and wires. People lost their homes, their farms; livestock froze to death. Nearly all of Creighton’s forty thousand households were blacked out.

As students in residence, we were ignorant of the devastation; we didn’t want the chaos to end. An ice storm was a dream come true for us – classes were cancelled, there was nowhere we had to be, no responsibilities. And we weren’t afraid of falling on ice. If anyone was going to die, it would be from drinking. A different sort of blackout.

Alice Cole Hall, the dorm where I lived, was the centre of the party because we never lost power. People said we had power because we shared a generator with Creighton General Hospital. Maybe that’s right, I don’t really know. I didn’t understand anything about power then.

PART ONE

Winter 1998

1

It is practical to put borders around this story, fuzzy as they are. So let’s say that the story begins the day we returned to campus from the Christmas holidays: Sunday, January 4, 1998. My dad drove me to school in the Jaguar he’d bought himself as a retirement gift on Boxing Day. I spent most of the drive pretending to be asleep, not because I didn’t like my dad, but because I didn’t really know how to sustain a conversation with him for three hours. We didn’t have a lot of common interests. He was seventy-one, which was older than some of my friends’ grandparents. Growing up, he never knew the names of my friends or teachers. He wouldn’t, for instance, have known the name Megan Main, even though she was my roommate. At eighteen, I was self-doubting, self-obsessed and a follower. But my dad had his own ideas about me, ideas that made me a credit to him, and it was easier to be who he thought I was, easier for both of us. On his desk at home, he kept a single photo of me; it was taken at Swiss Chalet when I was five, and it captured everything he felt he needed to know. Under the haze of a yellow-and-brown hanging lamp, I’m contemplating a structure built from creamer cups, sweetener packs and condiment bottles, my chin resting on my hand. Thoughtful, focused, independent. I was quiet around him because I wasn’t prepared to challenge that image. My dad was old, impatient with people, and had an unshakable sense of how things should be. I often worried that I’d say or do something stupid and reveal too much of myself.

I was eager to return to school that January. At that point, Regis was home. In August, my parents and I had moved back to Toronto after a five-year stint in LA, but the new condo felt to me like their space, not mine. I was a college student now, on my own, on to the next thing. I had spent most of the Christmas holidays watching TV while my mother suggested ways to brighten up my north-facing bedroom. I said, ‘Do whatever you like. I don’t really live here.’ This was also an excuse not to lift a finger.

My dad was a Regis alumnus, and he was pleased to see that I’d taken to the school. He’d whistled along to the radio for most of the ride there, but once we arrived, I didn’t want him to linger because I didn’t want anyone to see his Jag. Although family wealth was common at Regis, it was best to downplay it. When people knew you had a lot of money, you got judged more harshly. There was a girl on my floor whose highly recognizable surname linked her to a major Canadian grocery store chain. Behind her back, her presumed wealth was used to minimize her generosity (‘I’d give you a ride, too, if I had Daddy’s Saab’) and to barb any criticisms (‘You’d think she could afford to wax her moustache’). At Regis, being broke was de rigueur. It had been the opposite in LA, where everyone exaggerated their status whenever they could get away with it. At Regis, if the subject came up, which it didn’t very often, I told people my dad was an artist. It wasn’t totally untrue, he was an architect. A fairly famous one.

Before I pulled open the heavy wooden doors to Alice Cole Hall, Dad whistled at me from the sidewalk. I turned to face him, and he grinned in the same proud but embarrassing way he had when he pointed out that I was wearing mascara at eighth grade graduation. ‘Do you own this place or what?’

I forced a smile, looked around, hoped to God no one was watching us.

‘Let me get a picture,’ he said. ‘For your mom.’

Among my dad’s various false impressions was the idea that my mother and I were close. This assumption that all daughters are tightly bonded to their mothers must have come from his first marriage: my half sister, Val, was close to her mother. But my mom and I were not friends. Unlike my father, she didn’t view me with rose-coloured glasses – quite the opposite. Nothing impressed her. I suppose the upside of this was that it was also hard to disappoint her. She knew a few more of the basic bullet points of my life than my dad did – my roommate’s name, for instance – but she didn’t know anything about how we got along. She never asked.

I stood stiffly in the cold, duffle bag slung in front of me, while my dad fumbled with the camera.

This wasn’t the last time I saw my dad, but I think it’s accurate to say that this was the last time he saw me, or at least the version of me that he’d never previously had to question. The last time I was his bright, uncomplicated youngest daughter, with her best years ahead of her.

‘You probably noticed I like horses.’

This was the first thing Megan Main said to me. The first thing anyone at Regis ever said to me.

The week before I started at Regis in September, I got my dorm assignment in the mail and was devastated. Since receiving my acceptance in June, I had daydreamed about living in the Ex – James Exeter Hall, the huge coed tower I’d seen in the housing brochure – next to a long-haired, guitar-playing film major with a name like Hugo. I’d rehearsed the conversation that Hugo and I would be forced to have when, after several months of tension-filled, late-night talks about our childhoods and favourite movies, we admitted our feelings for each other and had to decide whether sex would ruin our friendship. It was very fashionable then to have guys as best friends and to worry, or fake worry, about ruining the friendship. Getting assigned to Alice Cole Hall, which was girls only and the least cool dorm at Regis, was a pretty major blow to my fantasies.

Long before I arrived, people had been shortening Alice Cole Hall to AlCo Hall, which would be an obvious joke for a normal dorm, but AlCo Hall was for girls who wore French braids for fun and volunteered at hospitals. It was the only dorm with ‘dry’ floors, which made it considerably more boring than the other two women’s dorms, all of which sat in a row on the same cul-de-sac at the edge of campus.

When I moved in, my dorm room had two cut-out construction paper hearts on the door with a cupid in between. One heart said Megan Main, Woodstock, NB; the other said Rosie Fisher, LA, Calif. The idea that someone on this floor thought I’d shorten my name to ‘Rosie,’ like some ’50s girl in a poodle skirt, was a good summation of the problem.

Megan was the first to move into our room. She wasn’t there when I arrived, but her bed was already made up with a dust ruffle and a horse-print duvet set. On her desk, there were two framed pictures: one of her with her parents at graduation and one of a guy in a backward ball cap posing in front of a Grand Am with his arms outstretched. Above her desk was a poster for the Penfield High School production of Anything Goes. I saw that horse decor, the cheesy boyfriend, the poster, and whatever hope I still had for my cool university life began to fade. Back then, I saw my peers in only two columns: ‘cool’ or ‘loser.’ Megan’s things confirmed that she was a loser. And I was pissed. There are confident, charismatic types who are considered cool no matter where they are or who they’re with, but I was not one of them. For average people like me, coolness is contingent. If you’re saddled with too much baggage, like a dork roommate in a dork dorm, coolness can slip completely out of reach.

Regis University was about a hundred years old, small, and elite. The campus spanned several blocks of scattered turn-of-the-century limestone structures, undifferentiated midcentury expansion buildings, and muddy playing fields. It was a hard school to get into, and the admissions team valorized the ‘well-rounded’: preppy, high-spirited, class president types. Leafing through my dad’s issues of Alumni Quarterly – chock-full of kids in fleece vests and canvas backpacks – I was heady with the idea of being a big fish in a small pond. The kids in the photos were nothing like me, but they weren’t better than me, either. There was a chance that I might impress them. At my high school in West Hollywood, where beautiful kids were literally creating youth culture on a weekly basis, it was impossible for me to impress anyone. I was background, plain rice. But at a provincial place like Regis, it seemed to me that I might convince people otherwise. Regis was a shining second chance; it was my first-choice school.

Megan and her uncool things, however, were a threat to my potential. Before even meeting her, I decided that if I didn’t want to be dragged down, the best strategy was to keep a distance from her. But a problem with my plan cropped up right away – Megan was an extremely kind person. When she eventually came back to our room that first day, carrying a stack of leaflets from the Student Activity Centre – I got double of everything! – I quickly realized I couldn’t just ignore her. In our first ten minutes together, she offered me stick-on hooks for my closet, a sachet of her mother’s homemade potpourri, and a roll of paper for ‘lining my drawers.’ When I sliced my index finger cutting the paper, she gave me a Band-Aid.

Megan was a dream roommate. She vacuumed both sides of our floor every Sunday, made us tea, and let me use her printer whenever I wanted, even though I never once paid for replacement toner. And lucky for me, Megan’s hectic schedule made her exceptionally easy to avoid outside our room. She had two jobs: regular weekday shifts in the cafeteria and a weekend gig at a stable on a professor’s farm. She was also an active member of both the equestrian and musical theatre clubs. The rest of the time, Megan was at the library, trying to get ahead. She had grown up around horses and wanted to be a large animal vet, which would eventually mean grad school. Megan was the first in her family to go to university, which is not something I could appreciate then. To me, university was not ‘the big leagues,’ it was just somewhere to spend four years because that’s what everyone did. My choices at Regis weren’t linked to any particular career ambition.

Of the two of us, I considered myself to be the sophisticated, worldwise one, but I must have seemed so lazy and immature to Megan. I didn’t have a job, I barely studied, I took no special care of my personal belongings. But at the time, it never seemed like Megan thought anything negative about me. She was just very capable and responsible while managing not to be smug about it.

So I led a double life. Behind our door, I reaped the benefits of being Megan’s roommate, and we enjoyed each other’s company. I ate the day-old desserts she brought me from the cafeteria, and I helped myself to her economy-sized bottle of Outrageous shampoo. Megan ironed my dress before the semiformal, and she helped me get puke stains out of the carpet the next morning, but it wasn’t all one-sided. I made her laugh. I liked to amuse her by drawing pictograms on her whiteboard when I took phone messages. Kyle, her boyfriend, might be represented as a tall drink of water, while the cafeteria could be a hot dog. If she guessed that the hot dog was Kyle, I’d tease her that she had a dirty mind. We were friends, more or less, but we weren’t often seen together outside of our room. Until she disappeared, I considered her a footnote to my life at Regis. That fall, if anyone asked me how I got along with my roommate, I’d say, ‘We’re not close.’

The person I wanted to be close with was Supriya Verma. Sue.

I noticed Sue in the common room at our first floor meeting in September. She was sitting with her legs up on a faded velour armchair, painting her toenails with Wite-Out. There were more chairs available, but all the other girls sat on the hardwood floor, too humble or too afraid to take up any space. Bev, our resident assistant, briefly paused her speech on the street names of various drugs – most of which, like grass, were embarrassingly outdated – to stare directly at Sue and say, ‘Those fumes can kill brain cells too, Supriya.’ Instead of apologizing, Sue looked up dispassionately and said, in her English accent, ‘Well, holy fuck. I had no idea.’ And then she got up and wandered away, still barefoot. Sue glowed with a natural-born confidence; I wanted to be close to her not just because that glow was dazzling, but because it was so abundant that others might mistake me as part of its source.

A few hours later, I had my first real encounter with Sue. I was taking my contacts out in front of the bathroom mirror when she came in wearing flip-flops and carrying a plastic bucket of toiletries. Megan, at the sink next to me, said, ‘Your eyes are all red, Ros. You OK?’ I met Sue’s glance in the mirror. ‘Yeah,’ I said, all casual. ‘I ran out of grass so I had to get high on school supplies.’

Sue snorted, and I felt a door nudge open for me. I would have traded all of Megan’s kindness for Sue’s approval.

In a normal dorm, Sue probably would have just ignored me, but in a nerd dorm, I was her best option. By mid-September, we were regularly knocking on each other’s doors. She told me she thought I was funny. One way I knew how to get her to laugh was by being a little bit mean, and the dorks in our dorm were sitting ducks. I didn’t feel like a mean person in my heart, but I was very talented at mocking people behind their backs.

Like me, Sue was somewhat of an outsider. She was born in Canada but had gone to boarding school in the UK since the age of ten. She didn’t fit with the Regis brand, but she didn’t aspire to either. She mocked the intramural sports, the theme nights at the bar, the endless loop of U2 and Counting Crows playing in the hall. The Regis leather jacket was the mainstay of this brand, and she called the girls who wore them ‘leatherettes,’ copycats. Why would anyone want to be one of the many? Another ponytailed, poli-sci major with an unironic passion for Jewel. Sue listened to Jane’s Addiction, had a lip ring, and smoked hand-rolled cigarettes. She went to classes swaddled in a moth-eaten cardigan but would later show up at the bar wearing a genuine Hermès scarf as a top. On Sue, scruffy looked stylish, and expensive looked effortless. She was all over the place, hard to figure out, and that gave her status at Regis without having to follow leatherette code. In my greatest flights of vanity, I believed that I was also different and interesting. That Sue recognized something special in me. But now I think what made me interesting was only my connection to Sue.

That January, the first thing I did when I got back to school was head for Sue’s room. Her rare single was at the end of the hall, just above the entrance to the cafeteria. From Sue’s window, we would watch other students come and go before deciding when to head down for meals. I liked to come up with nicknames for the people passing by: Skeletor for the tall, bony guy with a shaved head, Suicide Spice for the gothy girl in the dog collar, and – Sue’s personal favourite – Jesus Christ Superstar for the girl who wore long Laura Ashley–esque skirts and homely blouses.

When I opened the door to Sue’s room, she was looking at a spread of photos on her desk. She turned toward me and smiled. ‘About fucking time!’

Sue was updating her corkboard. Up to that point, the board had been a braggy collage of her cool pre-Regis life: pretty, kilted girls with coloured streaks in their hair and moody expressions; Declan, her gaunt-cheeked Irish boyfriend, with a guitar on his lap; a group of shirtless, long-haired boys on a beach somewhere in India, dancing with flaming torches. But now there were new photos going up. A shot of our friend Dutch had been added to the outskirts of her board. In the photo, he was lying on her bed with his head propped on his closed fist, staring right at the camera.

Dutch had been my friend first. We were in the same orientation group during frosh week. When our group leader got to him on roll call, he said, ‘Van Kampen? Like Van Halen?’

‘Like Van Kampen,’ Dutch said with a look of waning patience.

‘I’m going to call you Eddie,’ the guy said, baring his teeth and playing air guitar.

‘People call me Dutch,’ Dutch said.

I was in awe. You could just decide your name? I was wearing a hard hat then because the same group leader had made me put it on; he’d said my name for the week would be ‘Hard-head frosh,’ and if anyone asked why, I was supposed to shout, ‘Because I like to give head, hard!’

Over lunch on day two, Dutch told me to lose the stupid hat and then suggested we bail on parachute games to get drunk together and walk around. He said he noticed me mouthing the words to the song ‘Vienna’ earlier before ‘some asshole’ switched the track. ‘Fly’ was blaring at that moment, as it would be for much of the fall.

‘Billy Joel is our generation’s soundtrack. It’s practically primordial,’ Dutch said, leaning back on his chair and staring at me. ‘Think of what was playing during carpools, at the bowling alley –’

‘Orthodontist visits,’ I offered, remembering Dr Arkin’s schmaltzy radio, loud enough to be heard over drilling.

‘Never had one of those, but yes.’ He grinned; he did not need dental work. ‘Not everyone will admit to liking Billy Joel. I respect you for that. Very genuine of you. I’m not saying the guy’s cool, he’s not. But he’s part of us. Not like this Billy Ray shit.’

I never said I liked Billy Joel. I hadn’t even known ‘Vienna’ was a Billy Joel song before he said so. But I nodded in a way that attempted to convey, Yes, Billy Joel’s not cool, and yes, yes, I deserve your respect. I did not correct him that ‘Fly’ was by Sugar Ray, not Billy Ray – not knowing the name of the band you hated somehow seemed cooler.

Dutch wasn’t someone I would have bothered to have a crush on – he was too good looking for me, I could see that – but I did want his attention. I took off with Dutch after lunch, waiting nervously outside his dorm room in Herbert Hall – Regis’s boys-only residence, generally known as Pervert Hall – while he filled a water bottle with rye and ginger ale.

We walked away from campus, cutting through the student housing area to get downtown, and that was my first time on Heritage Street, Creighton’s famous main drag of dilapidated Victorians, all student rentals. Sitting proudly on their front porches, upper-year students sipped from Solo cups and beer bottles. Girls ran barefoot into the street to consume their friends in full-body hugs. Up on a roof, two dudes were hanging a banner that said: Grads ’98, Check Us Out & Masturbate!

Heritage Street had none of the overly eager smiles and jumpy, nervous energy of the dormitories; everyone seemed convinced of themselves, like they belonged exactly where they were. I was entranced.

Maybe it was the rye, but looking up at the sunlit trees, I was overcome with such a dizzying sensation of having found what I was searching for that when I looked down again, I was afraid that somehow I’d already lost it.

‘Do you play guitar?’ Dutch asked, noticing the Band-Aid on my finger as he passed me the bottle.

Without really thinking, I nodded. It wasn’t a total lie; I’d taken three lessons in tenth grade with a dick named Donald, who cringed when I asked him to teach me ‘What’s Up?’ by 4 Non Blondes, shattering my confidence in my own musical taste, perhaps permanently. But I felt like someone who could play guitar.

‘So we’ll jam sometime?’ he said.

‘For sure.’ I’d figure it out later.

Dutch didn’t ask me too much more, to my relief, but I learned a lot about him. He was from Windsor, had no siblings and had spent the last two years surfing and working in Tofino. He was older than most first years, which at least partially explained why he looked more mature, more mannish. He was tall with a stubbly face and lightly creased forehead, but there were subtler aspects to what made him seem older. That fall, most first-year guys were into trends like frosted tips, Vans, Oakleys, but Dutch’s style was more classic, in my opinion, more sophisticated. That afternoon, he wore Birkenstocks, Wayfarers, and a white button-down with the sleeves rolled up. His hair was neatly overgrown, no product.

We went as far as Eddy Street, the major retail strip in Creighton’s small downtown. Every window advertised back-to-school sales. We stopped for chips and cigarettes at the 7-Eleven, and then Dutch bought a Talking Heads CD at Radio Gaga, the used-book-and-music store. I flipped through the store’s ramshackle offerings, making sure to seem interested, but not interested enough in any one thing to have to talk about it.

Returning to campus down Heritage, we passed a group of girls sitting in a circle of lawn chairs on a driveway. One of them called out to Dutch and then came bouncing toward us. She said she knew him from Citizens of Insanity, his high school band back in Windsor. Apparently, his band was good enough to perform at actual bars. I wished, then, that I hadn’t told Dutch I played guitar. This girl had a tattoo of a daffodil on her forearm and an unopened beer bottle tucked jauntily into the pocket of her jean shorts. She had a natural, Noxzema-girl face that lit up with Dutch’s hug. Her curly, damp hair smelled like fresh cedar wood, and that fragrance seemed somehow connected to her beauty. Even if I used the same shampoo, I felt certain I could never emit that scent.

What would it be like to be her? Her best friend? How magical it would feel to simply exist in the easy company of someone like her. When Dutch introduced me, she glanced in my direction but said nothing.

Back at the dorms, as soon as I had the chance, I introduced Dutch to Sue. I knew they would like each other and that my association with each of them would raise my stock with the other. The first night we hung out, Sue spent forty-five minutes reading Dutch’s palm – fortune-telling was a skill she purported to have. I’m not sure what Dutch believed, but he liked the attention, her fingers tracing his palm.

Dutch and Sue were always flirtatious with one another – massaging each other’s feet and ‘falling asleep’ in the same bed – but they weren’t a couple. Sue was still technically involved with Declan back in London, and Dutch had an on-again, off-again girlfriend who was tree planting out west. But they were – I can still hear Sue say it now – such good friends. Whenever anyone suggested there was something going on between them, Sue would bark with incredulous laughter. But I’m sure they thought about fucking each other all the time.

I liked to think of us as a trio, but Sue and Dutch were king and queen. They called themselves the ‘2PAC’ after Tupac Shakur. Even though that made me feel left out, I still felt special to have brought them together. And it was easy to maintain my spot in the triangle because I had plenty of access to both of them. Sue and I had AlCo Hall in common, and Dutch and I were both English majors, sharing three classes. When Sue and Dutch did 2PAC-only things – like watching Twin Peaks in Dutch’s room after Tuesday night econ – I don’t think they were looking to exclude me, they just didn’t think about inviting me.

As the early January dusk settled outside Sue’s window, she turned on her desk lamp and handed me another photo of Dutch for consideration. ‘Doesn’t Dutch look like such a nerd here?’ she said. Sue had taken the picture at his twentieth birthday party in December, at a karaoke bar. I had baked him a cake in the common room kitchen and decorated it like a twenty-dollar bill. We’d stuffed ourselves on the walk to the bar. ‘He just looks like Dutch,’ I said, handing Sue back the photo.

Where I considered my own looks to have significant bandwidth – washing my hair and putting on concealer was the difference between looking like a rundown teen mom or a perky girl next door – truly good-looking people like Sue and Dutch didn’t seem to vary all that much to me.

Sue considered the photo again, and I bit my tongue. I’d been surprised at how much Dutch sucked at karaoke that night. The worst part was that you could tell he thought he was good. His version of ‘Creep’ was so earnest and intense that I figured it was a joke at first. He shut his eyes, stooped over the microphone, convulsed at the beginning of the chorus. Some people in the audience laughed, but he was too into himself to notice. I tried exchanging a pained look with Sue, but she was swaying and biting her lip, taking Dutch’s spitty, interminable performance just as seriously as he was. I wanted to run out the door. About fifteen minutes later, while his roommate, Stefan, was screeching his way through ‘Zombie,’ Dutch puked – green, from the cake frosting – all over the urinals and got us kicked out.

‘He gave me the sweetest phone call on New Year’s,’ Sue said. ‘Declan was off his head on coke, and I was feeling so neglected. We just talked and talked. Then Declan was all mad. I was like, What right do you have?’ She grinned mischievously. ‘I was going to punish him with no sex, but it’s just so bad for his ego. And anyway, the makeup sex is too good.’

What Sue could possibly have known about good sex at that age is a mystery to me now, but I was a virgin then, and I was rapt. I don’t think that I’ve personally experienced any sex as titillating to me as the sex I imagined other people were having back then.

Sue reached up high to put the second photo of Dutch on the board. Her T-shirt crept up, revealing her narrow waist. To me, Sue had the best body: long limbed, slim, streamlined. Her body was efficient. Mine, in contrast, felt loose and messy. My height and weight were average enough on a doctor’s chart, but my stomach wasn’t as flat as I thought it should be, and although I didn’t feel weak, my arms and legs were anything but sculpted. My body was unremarkable: a neutral, basically unnoticed entity. Sue liked to point out that my boobs were on the bigger side, like that should be a compliment, but I knew they weren’t great boobs. I’d been failing the pencil test since ninth grade.

Sue handed me a photo of the two of us taken right before the Christmas semiformal. I was doing the smile Sue taught me: fold your tongue up behind your teeth and giggle a little bit. Sue had one knee kicked up in a mock sexy pose. Although it was sexy. We’d done a lot of takes with her tripod. ‘I hate how I look here,’ she said. ‘And you’re smiling like an asshole.’ Of course I couldn’t pull off that smile. Sue gave me the photo, and I would later put it up in my room, asshole smile and all. It was the next best thing to being on her corkboard.

‘What do you think about me bringing Queenie over next year?’ she said, heading over to the window with her bag of Drum tobacco. ‘You love cats, right? When I saw Miss Q at Christmas, I was like, Absolutely not, I can’t leave you again!’

I didn’t love cats, didn’t even like them, but this request was the best thing that had ever happened to me. In December, people had started making plans for where they would live next year. Everyone was trying to reserve a house on or around Heritage Street. Even Megan had gone to see a place with some girls from our floor. I wanted to live with Sue, but I hadn’t wanted to be the first to bring it up in case Sue wasn’t into it. Some days, I couldn’t think of any reason why Sue would say no to me – we hung out all the time. But on other days, when I saw Sue from a distance around campus talking with other people, I imagined her getting many offers, and I’d think, If she wants to live with me, won’t she just ask? Then, right before the holidays, Sue told a story about a friend at some college in England whose housemate regularly sterilized her dildo in the kitchen. At the end of the story, Sue turned to me and said, ‘Please tell me I’m not going to find out you’re a nympho next year?’ It wasn’t exactly an invitation to live together, but I took it that way. Buoyed, I sent Sue an email over the holidays about a family friend who would be vacating a two-bedroom apartment in September that I described as ‘not right on Heritage (sorry!), but practically touching.’ Did she want me to inquire? When Sue didn’t write back, I couldn’t focus on anything else and fretted to the point of immovable irritability. I spent most of Christmas day rereading the email I sent, wondering how I could pass it off as a joke.

‘I’m down with cats,’ I said. I had to keep cool, try not to show her how elated I really felt. This was the hardest thing about being friends with Sue and Dutch. I was constantly watchful, continually looking for approval and trying to anticipate and adjust my tone and facial expressions to match theirs.

‘And yeah, I like the sound of being off Heritage,’ she said. ‘No one wants to be right on it.’

‘Totally.’

Sue handed me a cigarette and rolled another for herself. I opened the window and leaned out into the moist winter evening, watching a crowd of leatherettes make their way to the cafeteria. I wanted them to look up at me, framed in the buttery glow of Sue’s window. I felt like taking a bow. Supriya Verma would be my roommate.

The ice was coming, just hours away, but you couldn’t feel it yet.

2

It was that first Sunday dinner in January when I learned that Megan might be considered cute. It wasn’t something I was open to noticing on my own, mainly because Megan’s fashion sense was so oblivious. Regis was no LA, but people still paid basic attention to styles and brands. It was one thing to eschew trends, which was its own kind of cool – something Dutch could pull off – but Megan wore things that you could tell she thought were nice and that just made you feel bad for her, like pleated jeans that puffed out at the hips. She curled her bangs right up to the day she went missing.

Normally, Megan worked the dinner shift, but that night she had a tray like any regular student and came up to where I was sitting with Sue, Dutch, and Stefan. Megan’s presence in social situations made me self-conscious in two ways. I worried about the optics of being connected to a loser. But I also cared how I came across to her. On the one hand, I wanted her to know that I had status within an intimidating, good-looking crowd, but I didn’t like her to see me acting too exclusive or unkind. Even though people said otherwise later, I did care about Megan’s feelings. I cared what she thought of me. It was just that the opinions of Sue and Dutch mattered to me more.

‘Who’s this chick?’ Stefan asked, lifting his chin to indicate Megan. Dutch knew Megan because he was on our floor so often, but Stefan didn’t.

‘Christ, Stef. Chick? Evolve, why don’t you?’ Sue said. She made a gesture for Megan to sit. ‘Stefan, Megan.’ I was relieved that Sue took care of the introduction. Having a connection to a loser wasn’t a threat to Sue because she was never at risk of being mistaken for one.

Megan sat down. She had a steaming plate of shepherd’s pie, which made me a little embarrassed for her. Beef-based entrees were not something girls ate in the cafeteria. We chose things that were odourless, clean and spare – it came down to a lot of green salads, turkey slices and bagels with a bit of cream cheese.

Before Megan came along, the four of us were discussing a guy who’d been kicked out of Pervert Hall for using another student’s credit card to download internet porn. Dutch and Stefan knew the thief and were sympathetic to his situation.

‘Thing is,’ Dutch said, looking at Megan to bring her into the conversation, ‘it’s an easy mistake to make. He didn’t think there’d be any charges.’

‘Why would there not be charges?’ Sue asked.

‘Because you need a credit card to even get the free stuff, just to prove you’re eighteen or over,’ Stefan said. ‘And they make it very easy to click on the wrong shit.’

I nodded along, but I didn’t really understand. I had never seen porn online before, had no idea how it worked. Back in September, Chris, a guy I dated for three weeks over the summer, sent me a black-and-white video to download of a woman giving a horse a blow job, but I didn’t think that counted. I deleted it instantly. It made no sense to me why anyone would want to see that, or show it to someone, especially someone who had once tried to give him a blow job and gagged. Hard-head frosh, I really was not.

‘Whatever. I don’t feel sorry for him,’ Sue said. ‘Watching porn isn’t, like, a basic human right.’

‘It should be,’ Stefan said.

‘OK, so what I’m hearing is that you guys download a lot of porn?’ Sue said.

‘Not, like, habitually,’ Dutch said.

‘I just don’t get the appeal,’ Sue said, moving into a cross-legged position on her chair. ‘What’s sexy about static chicks on a computer screen?’ She looked at me, and part of me wanted to back her up, but I also wanted to seem like the type of girl who was relaxed about porn, who maybe even liked it. I didn’t say anything.

Stefan made a clucking noise. ‘You should be glad guys jerk off. Otherwise, we’d be like dogs on the dance floor.’ He stuck out his tongue and panted in Sue’s face. Sue shoved his shoulder. She had a habit of touching men in easy, teasing ways. It was not something I would have attempted; I didn’t know what sort of pressure to use or where exactly to touch.

‘I’ll lend you my Mastercard anytime if it means I never have to see that face again,’ I said to Stefan.

‘Master-bate card?’ Dutch said, grinning at me across the table. ‘What do you think, Rosie? Can I work with that? Make that funny somehow?’ Dutch was the only one who ended up calling me Rosie, and I didn’t mind when he said it.

‘You can do better,’ I said.

Dutch wrote for the Ragged Regis, a weekly humour paper. He was one of two first-years on the writing staff, in charge of dorm gossip and other ‘frosh topics of interest,’ and he liked to bounce ideas off me. He did a popular series of imagined dates between profs:

‘I like a good cocktail,’ said Professor Winifred Christie, Women’s Studies.

Professor Lou McNeely gestured down at his lap. ‘Lucky for you, Winnie,

I’ve recently been named the very – ahem – endowed chair of Public Affairs.’

Stefan started panting again, now in my face. The stereotype that guys were all horn dogs was a bit of a sore spot for me. Girls were supposed to act irritated and exhausted by all the men who couldn’t keep their hands off them, but no guy ever acted like he couldn’t keep his hands off me. It’s not that I wanted to be groped, but I felt I was missing out on something, some part of the whole experience. Maybe I wasn’t attractive enough for male attention.

‘Stefanimal’s just saying that guys have needs,’ Dutch said.

Then Megan spoke up. ‘Everyone does, right?’

I don’t want to overstate, but this might have been the comment that changed everything.

Stefan turned to Megan with a greedy smirk. ‘Go on.’

But Megan didn’t go on, or not in the direction he wanted. ‘The problem isn’t the pornography,’ she said. ‘It’s the theft. The violation.’

‘Allegedly, he found the guy’s card number in the computer room trash,’ Dutch said. ‘It’s not like he went into his wallet.’

‘Whose card was it?’ I asked.

Stefan shrugged. ‘The details are all hush-fucking-hush. No one’s allowed to tell us who the “victim” was. Some dink, probably.’

‘Really, Stef? Not wanting to cohabitate with a pervert who steals makes you a dick?’ Sue said.

‘I said dink.’

Sue held up her hands in a well-excuse-me gesture.

‘No, it’s totally different. A dick is a diiick…’ Stefan drew out the word. ‘Dicks have, like, leadership skills. They take control of a situation. A dink is just a little bitch who only wishes he could be a dick.’ Stefan sat back with the look of someone who would be totally fine, happy even, being called a dick.

Stefan was the kind of guy who prided himself on being shocking, particularly with girls. Earlier in the year, Sue had encouraged me to have a crush on him, but I said he was too immature. More to the point, I knew I was definitely not his type. He was a ‘skater’ with shaggy hair and baggy pants, and he thought his aesthetic made him counterculture and edgy. I pictured him being into a beanie-wearing girl with heavy eyeliner, multiple piercings, and tattoos. He regularly rated the girls who passed us in the cafeteria with either a one or a zero. A one was fuckable, a zero wasn’t. ‘It’s binary, so you can’t think too hard about it,’ he explained. ‘If you catch yourself needing to think, she’s a zero.’ If a ‘one’ went by, he held up one finger. I was afraid to ask what number I was. Once, he’d referred to me as ‘a poor man’s Jennifer Grey,’ which was more confusing than insulting because my hair’s not even curly, but I didn’t probe further. Over the summer, I’d made the mistake of asking Chris if he thought I was pretty, and his response had been, ‘You can look good.’

Sue had grown bored of all the dick talk and dismissed it by turning away from the guys and asking me, ‘Are we going to Phantoms tonight?’

One problem in our friendship was that Sue loved dancing and I didn’t. I didn’t think I was good at it; I never knew what to do with my arms. But I also didn’t like the ritual of it – the dressing up, the display. Sue said that if I wanted to find a guy to make out with, I needed to ‘green light’ more, smile, make eye contact. ‘Guys are stupid,’ she would say. ‘There’s no room for subtlety.’ Still, the idea of putting out signals felt desperate to me. At 2 am, when I saw so-so girls all tarted up in tube tops and mini skirts shivering in the line outside Burger King with everyone else, to me, they looked like a pack of ugly stepsisters, and I felt embarrassed for their efforts and failures. I thought the best thing to do in my position, the position of an average-looking person, was to play it low-key, to act like I had no skin in the game. Turning up at the bar in hiking boots, a pocket tee with a sweatshirt around my waist, and not dancing – or only joke-dancing – made me the kind of girl who didn’t need boys’ attention. The twisted part is that I hoped this persona would make me more attractive to boys. I wanted to make out as much as anyone, I wanted to lose my virginity, and weirdly, I tried to accomplish this by acting like I didn’t give a fuck. So I stood at the bar with the guys, drank, trashed the competition: She looks desperate, bad hair, maybe she should try not moving her arms. The media taught me that some guys went in for this sort of chill, disaffected Winona Ryder–type. But maybe they only liked Winona Ryder because she was hot?

‘I’m too tired,’ I told Sue. ‘Let’s just hang out here.’

Sue let out an exasperated sigh. I knew this side of me disappointed her. ‘You’ve just had two weeks holiday. You literally can’t be tired.’ She looked around the table. ‘Anyone else?’

‘What’s it like? I’ve never been there,’ Megan said, too polite not to respond to a question, or too oblivious to know it wasn’t directed at her.

Stefan looked at Megan in bewilderment. ‘Why not?’ Stefan said. ‘Don’t you have ID?’

‘Actually, I turned nineteen on New Year’s Day,’ Megan said.

I’d forgotten about Megan’s birthday. Other than Dutch, she was now the only one at the table who was legal drinking age. Not that being underage mattered much for the rest of us. Sue and I both had fake IDs – our foreign licences, unfamiliar and inscrutable to your average Creighton bouncer, had been easy to alter.

Stefan was the first to clue in and say happy birthday. Megan blushed as she thanked him. When she cleared her tray and left the cafeteria, Stefan looked at her, then the rest of us, and held up a finger. ‘One.’

3

The storm began a few hours after dinner that Sunday. I Googled weather records to confirm the accuracy of my memory. We were drinking Jack and Coke in Dutch and Stefan’s room, listening to Dutch play Radiohead on guitar at Sue’s request.

Stefan was grilling me about Megan. ‘What the fuck, Ros? How have I never met your roommate?’

‘We’re not close.’

‘Why don’t you ever bring her out?’

Stefan’s curiosity about Megan ran counter to all my beliefs about him and about how attraction should work. Megan was a dork; she shouldn’t – couldn’t – be desirable to him.

‘She’s not your type. Megan’s idea of a wild time is watching Party of Five in the common room with a bottle of Fruitopia,’ I said.

‘She is my type. She has needs,’ Stefan said.

No girls I knew discussed sex in terms of biological drive. That was the wrong way to talk about sex in the 90s, at least at Regis. It’s not that we were prudes – sex was a mark of desirability, and we wanted to be having it. But in front of guys, most girls at Regis, including Sue, acted like sex was something mainly men wanted, something we gave to them because we were generous and chill, not actually horny ourselves. We didn’t talk frankly about sexuality – not with guys, not with other girls – because the only people who did that were Dr Ruth and a handful of embarrassing hippie moms. I had a vision of Megan forty years down the road, the kind of woman who said, ‘Don’t be shy, we’re all girls here!’ before rolling off her one-piece bathing suit at the Y.

‘Back off, Stef. She’s so innocent,’ Sue said.

‘Not so innocent,’ I said. ‘She actually masturbates all the time.’

Stefan was wide eyed. ‘Really?’

I had heard her. Once. It was late after a theatre rehearsal, and she must have thought I was asleep. I recognized the catches in her breathing, the rustling of sheets, a barely suppressed moan. But I hadn’t intended for the story to turn Stefan on. It never occurred to me that guys would want to imagine this. Maybe it was naive of me, but I thought masturbation was in the same league as taking a shit: something guys could joke about, but not girls. Changing direction to something that might intimidate Stefan and keep him away from Megan, I said, ‘She has a boyfriend back home. He’s training to be a cop, so.’

Kyle and Megan had been together since tenth grade, and he went to community college somewhere in New Brunswick, but Megan said he was thinking of transferring to a police academy. Most girls I knew in high school with long-term boyfriends had broken up with them before university so that they wouldn’t be tied down. Staying with your high school sweetheart was something I associated with uncultured people from small towns. Well, except for Sue.

‘Do they have phone sex?’ Stefan asked.

‘They fuck like rabbits,’ I said.

‘That’s how I like to fuck,’ Stefan said, undeterred, jutting out his top teeth.