Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Polygon

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

WINNER OF THE GUARDIAN FICTION OF THE YEAR AWARD ONE OF THE LIST'S BEST SCOTTISH BOOKS OF ALL TIME Set in nineteen-sixties Glasgow, this novel portrays the struggles and conflicts of young working-class hero and would-be novelist Mat Craig, whose desire to define himself as an artist creates social and family tensions. This classic of Scottish twentieth-century literature is renowned for its vivid descriptions of Glasgow and the fight for individual creative expression; it remains as authentic and relevant more than fifty years after its original publication. Includes an Introduction by Alasdair Gray as well as Archie Hind's unfinished novel Fur Sadie and one of his essays 'Men of the Clyde'. * 'An exciting first novel worth a dozen more seasoned efforts' - Guardian 'The best novel ever written' - Skinny 'A touching insight into human strength and frailty' - Daily Mail

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 597

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

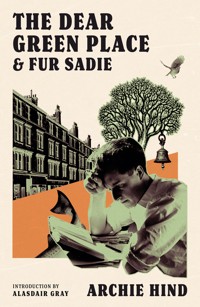

THE DEAR GREEN PLACE & FUR SADIE

THE DEAR GREEN PLACE & FUR SADIE

Archie Hind

Edited and Introduced by Alasdair Gray

This ebook edition published in 2011 by Birlinn Limited West Newington House Newington Road Edinburgh EH9 1QSwww.birlinn.co.uk

The Dear Green Place was first published in Great Britain in 1966 by New Authors Ltd This edition published in 2008 by Polygon, an imprint of Birlinn Ltd

Copyright © Archie Hind, 1966, 1973 and 2008 Introduction and Postscript copyright © Alasdair Gray, 2008

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

ebook ISBN: 978-0-85790-150-7

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

To Eleanor

CONTENTS

Introduction

The Dear Green Place

Fur Sadie

Editor’s Postscript

‘Men of the Clyde’

‘The Dear Green Place’ by Archie Hind and Peter Kelly

Introduction

In 1928 Archie Hind was born in Dalmarnock, an industrial part of east Glasgow. His father, a stoker on locomotive engines, worked for fifty-one years on the railways, with an interval as a soldier in World War One. Though liked by workmates and friends he was so bad a husband that when her son Archie was seven and older brother nine their mother left home with her two-year-old daughter. Ten years later the parents were reconciled; meanwhile the boys lived with their father and his widowed mother. The home Mrs Hind had abandoned, while decent and clean, was like most tenement homes in Glasgow between the wars, a room and kitchen with communal lavatory on an outside landing. Baths had to be taken in public bathhouses and Archie sometimes used these less than he wished, to stop people seeing bruises from his father’s beatings. These stopped when he and his brother grew strong enough to hit back.

The brutal part of his upbringing was not the most formative part and has no place in his novel The Dear Green Place, where the hero’s father is based on a more representative Glasgow dad, a tolerant, intelligent Marxist uncle. The mainstream of working-class thought and culture in Glasgow was the Socialism of the Independent Labour Party, the party George Orwell most favoured, and which returned seven Scottish MPs to Westminster before World War Two. After 1946 the best of these died or joined the Parliamentary Labour Party. Like most Socialists between the two great wars Archie’s people had been hopeful about the Russian Revolution and would have distrusted the U.S.S.R. more if the British government had not been so friendly to Fascist Italy, Germany and Spain.

Archie grew up with a love of literature and music – he and his brother both loved singing, and he learned piping in the Boys’ Brigade. Leaving school at fourteen he entered Beardmores, the largest engineering firm in Britain. It had built cars, planes, the first British airship, and still made great steam engines for ships and railway locomotives. By the late 1960s Scottish steam-powered industries were obsolete, but Archie joined the firm when World War Two was giving it a last profitable lease of life. For two years he was a messenger, reporting to Head Office on the progress of shafts and propellers shaped in the forges, turning sheds and workshops. He should have become an apprentice when sixteen, but his father wanted the higher wage Archie earned by shifting to a warehouse supplying local grocers. In 1945 or 6 he could have gone to university, since the last act of the government that brought Britain through the war had enabled any student to attend colleges of further education who passed the entrance exam. This would have been well within Archie’s power; but have meant even less money for his dad than an engineering apprenticeship. Archie only left home when eighteen and conscripted into the British Army. He served with the medical corps for two years in Singapore and Ceylon.

Which tells nothing about the birth and growth of his wide erudition and strong imagination through reading, close attention to recorded music and broadcasts, and intense discussion with those of similar interests. British professional folk often think creative imaginations unlikely outside their own social class – on first reading Ulysses Virginia Woolf thought James Joyce (despite his Jesuit and Dublin University education) had all the faults of a self-taught working man. Who in Glasgow could see the growth of an unusual mind in a twenty-year-old ex-Beardmores progress clerk, warehouseman and demobbed medical corps private? Jack Rillie could, the Glasgow University English lecturer who ran an extra-mural class in literature. Archie attended it and on Jack Rillie’s recommendation went to Newbattle Abbey, the Workers’ Further Education College in Midlothian. The Principal was the Orkney-born poet Edwin Muir who, with his wife Willa, were the foremost translators of German language novels by Broch, Musil and Kafka. Archie became a friend of both.

By now he had decided to write a book that he knew would never sell enough to support him – a book that would leave him a failure in the eyes of all but those who liked unusually careful writing. Soon after Newbattle Archie married Eleanor, a girl he had met through the Tollcross Park tennis club. She accepted him and his strange ambition while foreseeing the consequences, perhaps because her Jewish mother and Irish father came from people who did not identify worldly success with great achievements. Her mother had been brought from the Crimea to Scotland by parents escaping from Czarist pogroms, and like many Jews in Glasgow she attended left-wing meetings. At one of these she had met John Slane, a coalminer who learned to make spectacles while studying at night classes. They married and he became an optician successful enough, and rich enough, to buy Eleanor a beautiful Steinway grand piano and give it house room. But he hated her marriage to a man who supported his growing family by working as a social security clerk, trolley-bus driver and labourer in the municipal slaughterhouse between writing a novel that would never earn a supportive income. Archie and Eleanor made friends with writers and artists met through a new Glasgow Arts Centre which met in premises leased by the painter J. D. Ferguson and his wife Margaret Morris, founder of the Celtic Dance Theatre.

I met them in 1958 when they had three sons (Calum, Gavin, Martin) and young daughter Nellimeg, whose mental age was arrested at less than two years by minor epilepsy. Their last child Sheila was born five years later. I had recently left Glasgow Art School and the Hinds had the only welcoming home I knew where literature, painting and music were subjects of extended, enjoyable conversations. It was a room and kitchen flat like that where Archie had been born, but in Greenfield Street, Govan. The room held the children’s bunks so social life was always in the warm kitchen which, despite many evening visitors, never seemed overcrowded. These were years when London critics thought Osborne’s Look Back in Anger, Amis’s Lucky Jim, Braine’s Room at the Top, were a new school of literature created through the agency of the welfare state. These three works described working-class lads acquiring middle-class women. Archie and I thought they described nothing profound when compared with the best writings of Joyce and D. H. Lawrence, Hemingway and Scott Fitzgerald. We admired The Tin Drum, Catch-22, Slaughterhouse 5, and found we were both working on a novel about the only struggle we could take seriously – the struggle to make a work of art. This has been an important theme in poetry and fiction since Wordsworth’s Prelude. It inspired Archie most in the poetry of Yeats and fiction of Thomas Mann. He liked good jazz and American Blues, the songs of Edith Piaf and The Beatles, but thought most highly celebrated contemporary work – Beckett’s dramas, John Cage’s music, abstract expressionist painting and Warhol’s Campbell’s soup icons – indicated a thinning in the rich intellectual texture of Western culture. I was not so sure, but agreed that as writers we should maintain that texture. Our novels were both about low-income Glasgow artists doomed to failure, this coincidence worried us slightly, but we had chosen that theme long before meeting each other, and had to put up with it.

In the middle 1960s the Hinds moved to Dalkeith where Archie worked with Ferranti’s Pegasus, an early computer filling nearly the whole floor of a building. He left that job to finally complete his novel, and having completed it, worked as copy-taker in the Scottish Daily Mail, Edinburgh, while awaiting publication. In Milne’s Bar he sometimes conversed amicably about sport and politics with Hugh MacDiarmid. In 1966 the novel was published in Hutchinson’s New Author series. Its title, The Dear Green Place, was Archie’s translation of glas-chu or gles-con, Gaelic words that became Glasgow. They had previously been translated green hollow, green churchyard, greyhounds ferry, dear stream, and (in imperial days when it was the second largest and smokiest city in Britain) the grey forge or smithy. Archie’s translation is now generally accepted.

All good novels are historical – describe living people in a definite place and time. The Dear Green Place shows a city that had grown between 1800 and 1960, becoming for almost a century the second biggest in Britain. The earliest paragraphs give the layout – a city completely unlike London, for in Glasgow the homes of labourers, tradesmen and professional folk were intermingled with parks, shops, thriving factories with smoking chimneys and districts of old industrial wasteland. The time is about the 1950s when unemployment hardly existed and most of the labour force, though poorly housed by later standards, had the better wages and working conditions promised to the trade unions by the wartime coalition government. This Scottish region of the newly established British Welfare State gives Mat Craig the chance to occasionally dodge the commercial forces that, before 1939, would have made him an industrial serf, or political activist, or even destitute. He has enough room to exercise, however painfully, what was once a bourgeois or aristocratic privilege – the free will needed to attempt a work of art. The only other twentieth-century novel I know that places a writer’s struggle in an equally well imagined city is Nabokov’s novel The Gift.

Published in 1966, The Dear Green Place won four prizes: The Guardian Fiction of the Year, The Yorkshire Post‘s Best First Work, the Frederick Niven and Scottish Arts Council Awards. The Hinds returned to Glasgow when, as foreseen, The Dear Green Place had not earned enough to support them. Archie wrote revues performed in the Close Theatre and a witty, precise political column for the Scottish International magazine. He worked for the Easterhouse Project, a privately funded meeting place started to reduce violent crime among the young when the Easterhouse housing scheme still had few shops, no cafés, no playing-fields or provision for games and entertainment. Soon after, he was appointed to the position of Aberdeen City’s first Writer-in-Residence, later becoming copy-taker for the Aberdeen Press and Journal.

By this time he was working on his second novel, Fur Sadie. Fur is how many Glaswegians pronounce for, and the title associates it with Beethoven’s piano piece, Für Elise, in a way that will make perfect sense when you read it. The Scottish International published a small part in 1973, but all that Archie wrote of it is published here for the first time, for I believe it an astonishing achievement, although unfinished.

It is sometimes said that Scottish fiction has a more masculine bias than that of other lands, and though generally untrue it is true of much writing by authors like Alexander Trocchi, William MacIlvanney, Alan Sharp, Alasdair Gray and Irvine Welsh. But The Dear Green Place makes it hard to include Archie Hind among these and Fur Sadie makes it impossible. Here he transposes (as musicians say) the theme of artistic struggle into the person of a small, ordinary-seeming, middle-aged yet very attractive working-class housewife and mother. In a few episodes her life between infancy and menopause is presented as richly detailed, generally admirable, stunted by too little money and leisure, yet capable of much more. Most British descriptions of working-class people suggest how horrid, or comic, or admirable that they live that way. The narrative voice of Fur Sadie is free of such condescension. He knows that better lives are possible, and shows Sadie working for one. Her portrait is deeply historical. Her childhood is in the pre-television age when city children still sang and played in streets where motorcars were seldom seen – even professional folk seldom owned one, while coal and milk were still brought to houses in horse-drawn carts. When a middle-aged housewife, Sadie has had an electric geyser wired above the kitchen sink and no longer needs to heat cold water in a kettle. This innovation allows her time for music. There is a television set in her front room, and she can buy a second-hand piano and pay a tuner out of her housekeeping money without the expense worrying her husband. A social revolution has happened through which we see the sexual growth of a woman and man from adolescence through early marriage to late, sad maturity. No other author I know has shown a sexual relationship over many years with such casual, unsensational delicacy and truth.

And all that is essential to the tale of how a childhood friendship, and inherent, long-buried talent, at last combine with a good music teacher to bring Beethoven (no less!) alive in the mind and fingers of an apparently ordinary woman. The curious reader will wonder why this great fragment was not completed and how it might have ended. I will give my thoughts on this matter at the end of Fur Sadie.

This book ends with an example of Archie’s journalism from 1973. I wish this book also contained a selection from his early short stories (all lost) and some playscripts from the ten commissioned and performed between 1973 and 1990. I especially remember The Sugarolly Story, a satirical view of Glasgow’s social history from the start of World War One to the creation of Easterhouse housing scheme. This was performed by the Easterhouse Players in the Easterhouse Social Centre after Glasgow City Council at last built one. There was also Shoulder to Shoulder, a dramatised documentary of John MacLean’s life. The Ragged-Trousered Philanthropist, a Scottish dramatisation of Doonan’s building-trade novel, was the biggest and most successful, being the only one acted by a large professional company (7:84) in a well known theatre (The Citizens). The scripts of these have also been lost. This book must therefore be regarded as holding The Best Available Work of Archie Hind, and will deserve the attention of future lovers of Scottish literature.

The Dear Green Place and Fur Sadie have survived into a century where Archie’s forebodings about the thinning of the Western cultural tradition (now called dumbing-down), have come true. Intellectuals calling themselves Postmodern now say that objective truths do not exist, but are opinions in disguise. They can now lecture in universities upon anything they like because they can hold everything equally valuable, and declare many once valued things negligible. In a recent history of twentieth-century art international critics and dealers celebrate the triumph of Installation Art and announce that oil painting since Picasso is patriarchal and obsolete. Before that century ended a head of visual arts in Glasgow School of Art said no artist now needed to learn drawing. Glasgow University has a department of Creative Writing where the kind of novel Archie wrote is labelled literary fiction, and labelled as a genre along with crime, horror, science fiction and love stories of the sort publishers call chick lit. But when forthcoming catastrophes have moved the survivors back to serious agreement about what is important in Scottish life and art, The Dear Green Place and Fur Sadie will have survived also.

Alasdair Gray January 2008

THE DEAR GREEN PLACE

1

IN EVERY CITY you find these neighbourhoods. They are defined by accident – by a railway yard, a factory, a main road, a park. This particular district was reached from the town by a main road. On your left as you approached it was a public park; on your right, back from the road, was a railway embankment. Beyond the railway embankment lay stretches of derelict land of the kind seen on the edges of big cities. Broken down furnaces and kilns were still crumbling around where the claypits had once been worked. This derelict area was divided in part by brick walls, in part by some bits of drystane dyke, in part by some straggly hawthorn. Further on than this slag heaps and dumps for industrial refuse – here in Glasgow they are called coups – stretched down to the Clyde. The main road curved round the south end of the park, then entered abruptly into the neighbourhood. If you left the tram here and continued along the main road you pass the brownstone tenement, the ground floor of which contains the shops, the surgery, the pub. On the corner opposite the pub there is an old two-storey tenement, a newspaper shop, a telephone booth. Turning to the left here you come into a street with rows of council houses. Further down the road is the school. The streets traversing this are built up with red sandstone, three-storeyed tenements. Good houses. Beyond this street on the other side from the town were older tenements, few of them more than two storeys in height. Beyond these a golf course, then fields. Past the neighbourhood where the road led on out of the city it was bounded on one side by rows of houses, modern bungalows with raw-looking gardens, old square stone houses with dirty windows and untidy heaps of rhododendron encroaching on the shaggy lawns. On the other side of the road are sandpits dug down hundreds of feet into the earth.

But the street with the council houses. Stand there on a Saturday morning and you’ll see women coming back from the shops with their messages, their shopping baskets heavy laden, small tidy middle-aged women who clasp their purses as if they were weapons and can still tell a joint from a joint and stewing steak from brisket and make pots of broth from flank mutton. The children playing in the street are well clothed and reasonably polite. The young girl walking up towards the tram stop carries a long canvas case with a hockey stick in it and wears a fee-paying school blazer. The young men passing are mostly apprentices, the men mostly tradesmen. At eleven o’clock the group of men standing at the corner will disappear into the pub. These are the punters, the bookie and his runners. A quiet circumspect lot. You’ll see an occasional brief-case belonging to one or two young men who go to the University on a Glasgow Corporation grant. Later in the afternoon the men will appear wearing their blue scarves on their way to see the Rangers playing at home at Ibrox. If these middle-aged women have to scrape a bit at least they don’t have to pinch, the men can afford a pint and there are Christmas trees in the windows during the festive season. A quiet street. As these streets go a prosperous one.

In one of these council houses late on a September night there was a light still burning. It shone faintly on the windows, a dim amber light which had taken its colour from the room and from the old parchment coloured lampshade. Within the circle of light which the lamp cast on the surface of a table a man sat in the room, trying to write.

He was a short, dark, stocky man, with coarse black hair, a shadow on his unshaven cheeks. His rolled up shirt sleeves showed muscular forearms covered in dark hair which stopped sharply at the wrists. His small hands looked pale against the darkness of his arms. He was crouched over the paper on the table holding the pen in his hand tightly; his left arm was circled around the paper giving him the cramped appearance of a dull and unwilling schoolboy at his desk. For a couple of hours – ever since the other people in the house had gone to bed – he had been sitting writing.

Mat Craig looked up from his work towards the mantelpiece. The clock showed the time as ten past one. As it was usually about quarter of an hour fast then the right time would be five to one. He yawned and bowed his head over the papers again. All over the table within the circle of light shed by the lamp there were papers spread. He was sitting at the dining-table on one of the old mahogany chairs, its back shaped like a horse-collar. On the wall the miniature grandfather clock ticked slowly. The fire had stopped flickering and was now a dull glow, but he could still make out the individual books which were stuffed in the bookcases on either side of the mantelpiece – volumes of Marx, Lenin, Jack London, Daniel De Leon, translations of Anatole France, Eugene Sue, Zola. The books belonged to Mat’s father but he had read them himself with enthusiasm as a young man and in some way, although his interests had undergone a considerable shift – his own collection of books represented a different milieu – he still felt a loyalty to the ideas in these books and to the ardent idealism which had made him plough his way through their dusty leaves.

On one wall of the room was a sepia-coloured photograph of a locomotive, taken about the time of the First World War, with his paternal grandfather standing in front of it, leaning on a shunting pole, with a big black moustache like a raven’s wings stuck across his face. He had been a good Labour man in his day. At the side of the mantelpiece above one of the bookcases was a framed reproduction of one of Millet’s toilers.

Mat was ‘burning the midnight oil’. Perhaps there was a time when this act had for him the traditional connection with ideas of self-education and improvement which accompanies working-class political aspirations. But his sitting up writing now had nothing very much to do with these former hopes. Now his interests were nearer to the kind of thing represented by those names which spring to mind when we think of modern writing. But these interests, too, were apart from his need to write.

He was sitting crouched over the table and under the circle of light because he remembered something which had happened to him as a boy. He was sitting trying to recapture an experience which had happened to him a long time ago. This event, which he often recalled and which drove him to cover sheets of paper with his small cramped handwriting, was nothing more than his having once been overcome by a mood. He had been about ten at the time. The thing had happened after he had been playing football all afternoon and he had been walking home across a patch of waste ground. The late afternoon sun had burned through the dust and smoke which hung in the upper air and slanted down its inflamed pink light on to the hard packed ground round about him. His diffuse elongated shadow went before him as he walked. For no reason at all he had felt happy. A calm unaccountable feeling of pleasure.

Now, years later, he thought that he had gone through a type of mystic experience, although his happiness had in no way been ecstatic. it had been more of a commonplace satisfactory happiness unheightened by euphoria or anything in the nature of the occult. He often thought, too, that before this time, in his very early childhood, he must have gone through days of feeling like that. But by the time he was ten years old the experience must have been unusual to have retained itself on his memory. Since then he had almost repeated the experience but these repetitions were mere glimmerings, tenuous and fleeting, mere shades . . .

Now as he sat writing he was remembering how he had recently felt again one of those vague repetitions. Early in the evening he had come home from work just as dusk was falling over the city. A calm September evening with the dust and grime high in the air, the street lamps just lit, and women’s voices calling their children. As he walked up the road from the tram stop he could see the sky far away to the west, bright pink and blue like the illustrations in a child’s book, while towards him the light changed to a light sepia. Round the street lamps there hung a soft amber fuzz of light. Away far down the road into the grey east everything was black and smudged like a graphite drawing. There was a general hum of traffic and the sound of voices. Every now and then a window in one of the tenements would light up. Mat had felt moved and happy. He walked under some trees overhanging the pavement and a cobweb touched his face which had made him remember walking through a wood as a child. The familiar sensation of warmth and excitement came over him. The feeling he always had before he would start to write.

Although he felt tired he was quite peaceful. His fatigue helped him to write. Normally when he sat down under the lamplight he felt that his body was irksome to him, with its crude physical need for movement, its continual demands. He would want to scratch, or jump, or to fidget; his senses too would always be paying attention to other things; even his intellect, curious and avid, would be pulling him outwards, away from the paper. Not to mention worry, anxiety, duty. But now in the quietness, so that he could hear the coals crackling in the low fire, in the stillness of the room, with the enclosing lamplight shining just on the page, the things which he wrote about, and the words, took on a kind of reality.

After Mat had interrupted himself by looking towards the clock on the mantelpiece he couldn’t get started again. He felt sometimes that one of the disadvantages of writing out of his mood was that though he could pay attention to detail, to the sensuous surface of the writing, choosing the words carefully and, as it were, placing them on the page; although he could dream, feeling the words and the physical presences to which they referred, seeing every event, sensing their time and their rhythm, so that each sentence, each paragraph, had almost tactile existence for him, he found structure and invention impossible. Under the fatigue his mind simply refused to work so that he found his writing becoming a mere receptacle for memory and sense impressions. He had to go back reading over his work, reading through what he had written and then, following on the impetus, write another few sentences. He had to keep on doing this because of his inability to hold any general structure in his mind. As for invention, that was always done in the clear light of dawn when the mind was at its sharpest.

This time, instead of going on writing, he became caught up with some of his sentences. He usually reconstructed his sentences by an ingenious and wholly personal system of numbers, capital letters and various types of brackets, using this system to shift whole sentences back or forward in the paragraph or to adjust the position of a clause in the sentence. This created the difficulty that no one other than himself could have made a fair copy from the page, even if they could read the small cramped and practically illegible handwriting. Sometime, he thought, I’ll get some pens with different coloured inks.

He had stopped writing now and with his chin cupped in his hand he sat looking at the paper. He thought that perhaps the story he was working on was quite good, and not badly written. The trouble was that good writing was ten a penny and that the story was also a little diffuse – slight. It needed some plain numb words to make it active, to get the feeling of narrative into it. And when he thought of the slightness of the thing he felt himself give an internal blush. It was slight and had a little touch of Romantic Irony in it because he didn’t want to say too much, be too serious. He became so involved with everything he wrote that he was afraid of too much emotion. Rightly. On the other hand, the writers whom he admired, any real writer, knocked and slapped their material about in quite a cavalier fashion. I could do it in the morning, he thought, if only . . . Sometimes he saw himself quite clearly as an object and could feel a certain amount of pity for the poor character in a cleft stick. The writer who couldn’t really write.

‘Damn it.’ He almost spoke out loud and as he pushed the papers away from him, finishing with them, he felt suddenly a dry and brittle mood come over him. ‘When I get to bed I’ll do some grand writing in my head.’ He lifted his feet on to the table and started to smoke a cigarette. Immediately he felt a twinge of conscience. All the writers who ever got anything done insisted on discipline. All right – discipline, work. He put his cigarette into his left hand, swung his feet down and picked up his pen. As he started to coax himself back into the mood he was tempted by the thought that the difficulty was in his point of view, or that he needed to wait a bit until he had grown more. A complete change of style and attitude would make it all so much easier. It was true – but it would be better to think of that later – one couldn’t think and work at the same time. And work came first.

He gathered up the papers on which he had been working and clipped them together with a paper clip. Then as he put them aside he looked round the table at the bundles of manuscript. Jotters full of notes, dossiers full of bits of dog-eared paper and typescript, single scraps of paper with notes on them which he thought too valuable to throw away. He had a habit of keeping every single thing that he had written, all in a big cardboard box, and every time he sat down to write he’d spread them around him on the table for comfort. Faced with a single scrap of paper he found himself unable to write a word, but with his ‘bits and pieces’ about him he was able to write away quite happily. He took a bulky folder, the biggest of all his ‘bits and pieces’ and laid it in front of him on the table with a sigh of satisfaction. On the front of the folder, typed on a piece of white paper and stuck on, was the motto ‘Rutherglen’s wee roon red lums reek briskly’. Beneath that was a reproduction of the City of Glasgow’s coat-of-arms with its tree, its bird, its fish and its bell. Beneath that again was typed a little piece of doggerel verse which is known to all Glasgow school children.

This is the tree that never grew,

This is the bird that never flew,

This is the fish that never swam,

This is the bell that never rang.

On the coat-of-arms there were printed the words Let Glasgow Flourish. Mat sat and looked at it for a while, then he printed the word Lord in front of it and the words by the preaching of the Word after it, and restored the modern truncated motto to its old length and meaning.

Lord, Let Glasgow Flourish by the Preaching of the Word.

As he made the addition he smiled wryly to himself as if at some private joke. Then he muttered to himself in supplication, with ironic fervency, ‘Lord, let Glasgow flourish by the preaching of the Word,’ and opened the folder, exposing the first neatly typed page.

The manuscript began with the words ‘The Clyde made Glasgow and Glasgow made the Clyde’. It had been some time since he had opened the folder, though he had thought of it often with a warm feeling. As he read what he had written he was rather surprised that he only remembered it slightly. The words came to him now as almost new and he read on, curious to know what he had written these years ago. The typescript continued: ‘For many centuries there were fishermen’s huts around the spot where the old Molendinar burn flowed into the Clyde, where the shallows of the Clyde occurred, where the travellers crossed who made their way from the North-west parts of Scotland down to the South. Some authorities have it that this place where St Mungo, or to give him his proper Celtic name St Kentigern, built his little church was given the Gaelic name Gles Chu, meaning “the dear green place”, and that the present name of Glasgow is a corruption of those two Gaelic words. The deargreen place – as it must have been. Even late into the Eighteenth Century when the modern city that is Glasgow had begun to grow it was talked about as “the most beautiful little town in all Britain”. In the Sixth Century St Mungo had built a mission there, building it like any inn or hostelry at the most likely place to catch the customers, or converts, at the spot where the drovers or travellers would pause before crossing the ford. Being on the West coast of Scotland its connections were with the Celtic Christian culture in Ireland and so it became an ecclesiastical town. In the Fifteenth Century a University was built and Glasgow remained a religious centre until the European Reformation when it acquired with vengeance the Protestant ethic and its natives turned their hands with much zeal to worldly things. These same natives had always been pugnacious; the Romans in an earlier day had found them an intolerable nuisance; and in the Tenth Century they maintained their reputation for pugnacity by knocking spots off the Danes down on the Ayrshire coast. Thereafter they mixed almost solely with people of their own racial type. During The Industrial Revolution when Glasgow suffered a great influx of people it was from Ireland and the West Highlands of Scotland that the people came so that even today the characteristic Glasgow type is short, stocky and dark like his very remote Celtic-Iberian forebears.

‘When St Mungo fished in the Clyde from his leaky coracle the source of the river was a different one from that of today. The old rhyme goes,

“The Tweed, the Annan, and the Clyde,

A’ rin oot o’ ae hillside,”

and this is not now the case. It is probable that, as some people claim, a farmer led the original Clyde burn, which rose away back in the hills, along a ditch and into the Elvan and thus on South into the Solway. This to prevent the burn from flooding his fields.’

Beside this sentence Mat marked the word ‘avulsion’. As he printed the word in the margin he felt a strange kind of satisfaction. Then he went on reading his manuscript.

‘It happened that about the same time the Glasgow merchants were howking at the river bed further downstream in order to make the deep channel which allowed Glasgow to become the great sea port which nature intended it to be.’

Again in the margin beside this sentence Mat printed another word, in alternative forms ‘alluvion’ and ‘alluvium’. Then he added the sentence: ‘And thus the wiseacres are confirmed in their saying that Glasgow and the Clyde were mutually responsible for one another’s being.’ He found the idea that the river had been tamed, or ‘domesticated’, for the sake of all this husbandry, that the big river had become something of a human artifact, he found this idea exciting and satisfying. The rest of the manuscript went on to describe the river itself.

‘A parochial historian refers to the “dim prophetic instinct in the country” which anticipates the wealth which was one day to come and speaks of one of the oldest traditions connected with the river, which tells of the three hundred Strathclyde chiefs who each wore a torque of pure gold “washed from the sands of Glengonar, or found in the mud of the Elvan”. They say that German and English prospectors came to look for gold in the Leadhills. Mines are mentioned in the very oldest records connected with the Clyde district. Gold, however, was never found in abundance and the country had to await the coming of the modern alchemists who could transmute the grey ores and black minerals which were found in abundance into a precious form. Certainly as we move among the soft greenery of that lovely strath, from its source past the grey mossy slopes and thymy banks, through the quiet hills, still, with no other sound but the cry of the curlew, the bleat of the lamb, the hum of the wandering bee, and the splash of water on stone, down to the broad valley of its middle waters with its rolling bare countryside, then the picturesque falls and rippling affluents, the pastoral delights and musing solitudes of its great Ducal estates with their fine old trees, broad pleached alleys, and far stretching vistas; down from the idyllic and uncertain past into the reaches ofthe Clyde where the air begins to darken, the horizon is smudged, and intermingled with grazing fields, trees, farms, and gardens are coal heaps, pit heads, corrugated iron sheds, foundries, machine shops, bings and mills; certainly we begin to see what the centuries had waited for with bated breath, what had been anticipated by that “dim prophetic instinct”. For here are the alembics, the retorts, and crucibles, funnels and furnaces, the apparatus and paraphernalia of the modern alchemists who transmute the grey ores and base metals of the district into glittering wealth.’

Mat smiled at this section. He remembered copying from a parochial historian the plummy bits of prose. He had enjoyed the plushy sounds of the words ‘rippling affluents’ and ‘pleached alleys’ – whatever ‘pleached’ meant. Looking up the dictionary which was lying on the floor beside his chair he read the words: ‘to intertwine the branches of; as a hedge’. Then he read on.

‘We move further along the loops which the river now takes round the towns of Hamilton, Bothwell, Blantyre, through Carmyle and into Glasgow. The mossy slopes harden into packed banks of black hardened mud, the soft greenery is a virid colour from the stretches of soda waste, the rippling affluents gush from cast iron pipes, an oily chemical sediment; we hear now the din of machinery, the thumping of hammers and the hiss and blast of steam and gas. Then the din dies down to a rattle and we come to the idyllic spot where the gentle oxen crossed and the little Molendinar burn flowed into the broad shallows of the river; the spot which the Gaels named Gles Chu, the spot where as legend had it St Mungo recovered his lost ring from the belly of a salmon. The little valley of the Molendinar is now stopped with two centuries of refuse – soap, tallow, cotton waste, slag, soda, bits of leather, broken pottery, tar and caoutchouc – the waste products of a dozen industries and a million lives, and it is built over with slums, yards, streets, and factories. A few hundred yards downstream from the broad shallows of the river there is now a deep artificial channel which will take ships of the deepest draught, great ocean-going liners. It is now spanned bybridges of steel and grey granite. We are now in the heart of the industrial world; not just the mercantile, commercial, industrial metropolis which is Glasgow, but at the heart of Industry itself, for in this spot was cradled the great movement, the Industrial Revolution, which transformed the face of the World. Take a map and a pair of compasses and insert the point of the compasses into the spot – tenderly! Gles Chu! – now transcribe a circle and you encompass the stamping grounds of many of the great men who made the Industrial Revolution possible. Adam Smith, the economist of Laisser-faire, who held the Chair of Logic and Moral Philosophy at Glasgow University. Watt, to whom we owe the steam engine; Murdoch – gas illumination; Neilson – the blast furnace; Symington and Bell – the steam ship; Rigby – the steam hammer; MacIntosh – the use of rubber; Tennent – industrial chemistry; Napier and Elder – the marine engine and screw propulsion; Paterson – the Bank of England. Here for the first time the Monteiths wove the muslin which clothed the Asiatic in his flowing robes and turbans; here were woven the zephyrs, inkles, and muslins which were to clothe the Americas: Dave Dale, before he married his daughter to Robert Owen, was carrying out experiments in industrial welfare; from here came MacAdam of the roadway and Telford of the bridges.’

At this point Mat must have ceased to type for the manuscript continued in his small cramped hand. Instead of going on reading he took up his pen and started to make more notes. The last passage had moved him, it had evoked the memory of so many things; for where the river had taken these last loops into Glasgow had been his own stamping ground in his first years as a child, and the banks of the river with all its old factories and mills; from away out in Carmyle right into the heart of the city, right to the spot where St. Mungo had fished, all was as familiar to him, more familiar to him than the room in which he sat. He knew every waste pipe that gushed its mucky sediment into the river, every path along its bank, every forsaken spot and lonely stretch where no one but children ever went, where between long factory walls and the river there were narrow paths that led merely from one open stretch of dumping ground to the next. Here he had played as a child in the oldest industrial landscape in the world, amongst the oldest factories in the world, and it had been through this landscape that he had walked when he had once felt so unaccountably happy.

Inside one of these loops in the river he had been born, in a tenement building surrounded by factories. Nearby, in a house overlooking the yard of an electric power station, where coal trucks were shunted into a machine and tilted over to empty the coal into the furnaces, underneath the massive chimneys, here his mother had been born. And here, in the midst of the alchemist’s paraphernalia, his grandfather had worked and raised his family, weaving in a nearby factory the muslins that clothed the far away Asiatic. One of his earliest memories was of getting a licking from his father when he had come home all soaked and muddy from falling into the water. On some parts of the river where the banks were very steep the children used to climb down them, then on to one of the iron pipes which projected over the water, lie down with their legs straddling the pipe and hold their hands in the mucky torrent which gushed out of its mouth. The fascination of the game was in creating a variety of effects, as for instance if the hands were pressed round the lip of the pipe the increased pressure scooted the water far out into the river in a delightful curve; another way of holding the hands over the pipe would cause the water to spread out in a smooth fan with a ragged tassel of drips at its base where it fell into the water; and there was the additional fascination of feeling the force of the water as it gushed from the pipe.

For a long time Mat sat without writing any more. He was thinking of these days long ago which his passage about the Clyde had evoked. He was trying now to remember whether his grandfather had been standing or sitting in front of the loom on the day long ago when Mat had carried his pieces of bread and cheese and the can of hot soup down to the mill where he had worked. But all he could remember were his grandfather’s deft hands and the taut lines of cotton which jerked up and down at the back of the machine, and of course his grandfather’s mop of white hair on top of his magnificently shaped long head. He had a fierce curve to his nose, a pair of arrogant hooded blue eyes and was as deaf as a door-post; his temper belied his appearance as he was the mildest of men and Mat remembered especially the way he would say ‘Eh!’ and curve his hand over the back of his ear. All his family, his children and his grandchildren called him ‘Faither’ and a great many myths were current in the Devlin family about him, all indicating that he was a poor man mainly because of his wilful stubborn integrity. However, he had spawned in the tenement where he lived an extravagant family of red-haired children, all talented in a completely useless way, the same as he had been. This background which that family had created, against which Mat grew up, was one which he loved to remember and which was always mingled, somehow, with his thoughts of the mucky old river about which he so often tried to write.

Mat looked up towards the clock in the room again. Its hands pointed to two-thirty which would make the real time two-fifteen. All this time he hadn’t been writing at all, just sitting dreaming. Anyway he was too tired to go on. He got up and went into the scullery to drink a glass of water, then came back into the room to smoke another cigarette. He tried to count how long he had been up without sleep. He had risen that morning at seven-thirty, which was now nineteen hours away, and he had had hardly any sleep the night before. However, the next day was Sunday. He would get a long lie, a read at the papers, then perhaps it would be back to writing again.

The last thing Mat did before going through to his bedroom was to brush up the ashes that had fallen into the hearth.

2

THE OFFICE WHERE Mat worked was outside the city. Instead of the usual thing for office workers who more often travelled into the city, Mat travelled outwards. The tram took the main road out of Glasgow in the direction of Hamilton and Mat had to get off and walk down southwards towards the banks of the river. Again he was in the midst of that strange mixed landscape which occurs on the skirts of big industrial cities. There were old farmhouses, grass fields, ploughed fields, scraggy hawthorn hedges, then open spaces full of rank grass growing over the debris from the heavy engineering industry – rusty boilers, lumps of concrete with the rusty dowelling still sticking out of them – and all over this, in the early morning sun, a natural freshness with the green grass growing hard up against the frozen slag.

The factory itself was old, just a collection of brick buildings which had gradually assumed their present functions as the various different types of plant were installed in them. It was an old family business at one time, and though the family were still connected with it in a vague way it had been a couple of generations since they had anything to do with the management. The type of work done in the factory was traditional in the district. Cotton finishing – the bleaching, shrinking, singeing, and mercerising of the cottons which had been woven in the local mills. Nowadays there was as much work came from Lancashire as did locally. The mills had gone but the business had grown, become modern and fairly prosperous.

The approach to the factory was down a long hedged lane, past a farmhouse, and a small water reservoir. On the other side of the factory, facing the river, was a row of small cottages, built of stone and very old. The part of the factory next to the cottages had been built over and around them, so that now only the stone fronts showed. They looked like little pieces of semi-precious stone set into the rough crumbling brick of the factory. Some of the factory workers lived in these little houses along with their families.

When Mat passed the old time clock he noticed that it was still early but he went upstairs to the empty office. First thing in the morning the office had a shining pristine look. Everything was either locked away in the safe or tucked away in the files and nowhere was there a single scrap of paper in sight to indicate that work was ever done in the place. The typewriters and the big electric calculating machine lay hooded on the desks, the mahogany woodwork had an opulent shine, the metal topped desks and paper racks were free of dust, the brown linoleum was waxed so that Mat’s shoes skited on its surface. It was the most perfectly run office that Mat had ever had anything to do with. It had a written constitution, a system of checks and balances, a Code Napoleon, in which every possible contingency was provided for. There was a set of wooden boards with typed instructions pasted to them laying down the exact procedure for every situation which arose in the office. If a bag of nails was purchased for the use of the factory, its purchase and reception in the factory was carefully noted down and checked, the advice note was signed and filed away for collation against the account, a record of the cost was kept so that the price of any past or future purchases could be checked against the current one, then the cost was marked against a particular operation, the amounts of the bill duly noted in the various ledgers and day books in the proper double entry manner. All these tasks, with the order in which they were to be carried out, were written down on the wooden boards so that no mistake could possibly be made. Provision was made for everything except deliberate human malice. Human error was certainly not discounted and every task which involved calculation was checked twice.

The author of this system, the secretary of the firm, was a Mr McDaid, an elderly inhibited businessman of the old type, very Scottish, a kirk elder and teetotaller. He was a complete mystery to Mat. Not that Mat didn’t understand and sympathise with the man’s fear of risk. It was not the neurotic ulcer-creating fear of impending doom of the modern businessman that moved Mr McDaid, but an active and intelligent estimation of the kind of events to expect and the right thing to do about them. What was a mystery to Mat was how Mr McDaid got on outside the office when he was not able to put his system of checks and balances into operation. All that Mat knew about him was that he was a nervous, almost incompetent car driver and that his wife pulled down the blinds during the day to prevent the sunshine from ruining the furniture. He was quite a kindly man in many ways but fussy and rather ruthless towards the things he didn’t understand. The man’s perfectionism was personally irksome to Mat and depressed him in the same way that army routine had done.

Mat went through to one of the front rooms of the office and looked out over the grey muddy river. There was a fairly heavy spate on and where the river narrowed there was a rough striata running up and down the surface of the water. On the other side of the river, about three hundred yards from the office window, there was a great square brick power station completely blocking the view. A little way down to Mat’s right a weir curved into the stream and the water poured over it in a smooth liquid curve. On either side of the weir masses of foliage, small tree trunks and mud had heaped up in a squalid untidy pile.

For some reason the view fascinated Mat. It was a particular kind of landscape, a mixture of human and natural industry which intrigued him. Each aspect seemed to take on and mingle with some of the characteristics of the other. The grass and willows growing along the banks of the river were grey and sooty looking; the weeds, dockens, dandelions and dog’s flourish were tattered and defiantly stunted; the mud selvedge of the river showed rainbow tints from an oily sediment. But the brick buildings were heavily marked from the weather, the power station had great damp streaks running down it, the pointing on the factory was all crumbled and the bricks eaten with damp and covered with a thin green mossy slime.

There was a vague hum of machinery coming from somewhere inside the building and the faint clank of trucks from somewhere on the other bank of the river. Above it all, the roar and splash of the water.

Something could be done with this atmosphere, just simply out of the landscape. Mat remembered a description of Rome which he had read somewhere. It had been described as a kind of half buried history where everything, the houses, streets, monuments, churches were a huge physical agglomeration of the debris of history. Yet all of Rome could not have fascinated Mat half so much as the acts of the solid Scottish burghers which were embodied in this crumbling industrial landscape. There was something of their tradition even in this modern office in the bound ledgers, the carefully kept files, the records, catalogues and inventories, the meticulousness, the physical prosperity. Away on the other side of the river, hidden from Mat beneath a haze of smoke, was the old Royal Burgh of Rutherglen. That haze, that smoke, was for him a presence which caused in him the thrill of the imaginative excitement and brought out in him the lust for creation. He thought of the peculiar boast which the people of Rutherglen had and which he had written on the cover of his magnum opus – ‘Rutherglen’s wee roon red lums reek briskly’. This mixture of modesty, complacency, and sheer canniness thrilled Mat. He imagined these old burghers of the eighteenth century with their great heavy walking sticks, their breeches and embroidered coats, their horn snuff boxes, their freemasonry, their mixture of canniness and daring, their overwhelmingly male pursuits; and their women forming a solid domestic background with their crimping irons, warming pans, samplers, linen, and heavy cutlery and their utterly dull and regular lives. Mat felt a tremendous nostalgia for these people and their way of life. He loved the heavy solidity of the old burghers; their substantial broad fronts spread with waistcoat and fob, their great mansions, their big leather boots, their conservative art, their good plain substantial mundane safety.

Mat’s thoughts were interrupted by the sound of feet on the wooden stairs. He heard the cheerful early morning sound of voices shouting to one another. He went out to the top of the stairs and shouted down.

‘Hurry up you lazy bugger.’

Bill, the head clerk, was coming up the stairs making a deliberate cheerful clatter. He interrupted Mat. ‘That wife of yours fairly kicks you out of bed these mornings.’

‘I’m just dying to get to work.’

‘Don’t worry, we’ll make you work all right.’ Bill was opening the door into the office which he and Mat shared. Although it was a bright warm morning he wore a coat and hat. He took them off, hung them up, fumbled for his keys, fiddled about with his pens, and put on his specs all at the same time. Next door the typists were removing their coats, changing their shoes, opening cupboards and desks, taking the covers from machines.

Mat and Bill were very fond of one another but their relationship was strange. Bill felt sorry for Mat because of his gentle ways and his apparent naïveté. Mat in some strange way sensed Bill’s feeling and because of this acted out the part which Bill had given him. He found himself doing this often with people. Not deliberately or dishonestly or with any intention to deceive but because he became as they saw him. Bill’s attitude towards Mat was one of affectionate, slightly condescending, teasing.

Occasionally Mat went to visit Bill at his home. Before Mat’s marriage he had gone regularly on a Friday night. Bill lived