Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

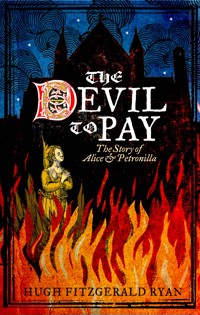

Kilkenny, 1324. Alice Kyteler, outspoken daughter of a wealthy Flemish banker, has survived four husbands and is beset by the gossip and rivalry of a medieval Anglo-Norman town. Her beautiful maid is Petronilla, child of an itinerant shoemaker, her lover Sir Arnaud le Poer is seneschal and lord of south Leinster. Her nemesis is Richard de Ledrede, English Fransciscan, scholar, poet and now bishop of Ossory, determined to reassert clerical power and restore the dilapidated cathedral. To him Alice embodies the moral laxity of the age, her irreverence and knowlege of healing feeding his anger and obsession with witchcraft. Outside the city walls the native Irish are resurgent after 150 years of dispossession. In the streets of Kilkenny, crowds gather around the stake. In The Devil to Pay, HUGH RYAN tells the true story of Alice and Petronilla – portrayed against a backdrop of the struggles between Norman and Gael – bringing to life a remarkable tapestry of this pivotal era in Irish history.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 435

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2010

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

This story is for my grandchildren (in due course), who have bewitched me in many ways: Sally Anne, who magicked me into a grandfather; Victor and Leo, cheerful companions; Josephine, brave and affectionate; Alice, ‘the girl what fell in the duck-pond’; Mike, who keeps me from getting above myself and Luke and Alex, with their own new magic.

Most of all it is for Margaret, my young wife in Kilkenny, still weaving her gentle spell.

Contents

Title PageEpigraphMapsPROLOGUEONETWOTHREEFOURFIVESIXSEVENEIGHTNINETENELEVENTWELVETHIRTEENFOURTEENFIFTEENSIXTEENSEVENTEENEIGHTEENNINETEENTWENTYTWENTY-ONEGLOSSARYCopyright

PROLOGUE

Multi reges ante fuerunt

Mundi passus qui transierunt

Ubi iam sunt?

(Where now the many kings of former times who ran this earthly course?)

—Richard de Ledrede

IN THE YEAR of Our Lord 1169, a full century after Hastings, a company of desperate Norman knights established a foothold on a rocky headland in south Wexford. They came with guarantees of reward from Dermot, the banished king of Leinster, should they succeed in restoring him to his lands. They had Dermot’s word, but as security for his promises they brought weapons, armour and horses.

They had, as further justification, the notion that the Pope had, at some time in the past, urged the king of England to bring the Irish people back to the true practice of the faith. The king, the flamboyant Henry II, had other concerns but after the feudal custom of the time, he farmed the task out to his vassal, Richard de Clare, the formidable Earl of Pembroke, known to all as Strongbow.

These first knights spent a bleak winter on that windswept promontory. They constructed a fortification. They repelled attacks by the natives. They butchered emissaries of peace, hurling them from vertiginous crags to the jagged rocks and the surging waves. They let it be known that English law, backed by Norman might, had arrived in Ireland. They waited for Strongbow and within a bare four years Strongbow was Lord of Leinster and son-in-law to the devious Dermot of the Foreigners. He could have been king but he was constrained by his word to Henry Plantagenet.

Henry came to look over his new lands. He entertained the Irish chiefs over a long Yuletide and bound them to him as sworn vassals. The chiefs enjoyed the feasting and gleemen, the jesters and the bonhomie. They drank the wines of this great king’s French dominions. They pondered how they might use him against their neighbours in their incessant tribal wars. Departing, they shrugged at the oath, but they were ensnared in a web, tripped by their own words. The web was loose and flimsy, but it was enough to start with.

The Irish called the little river Bréagach, the river of deceit. In summer it was bland and peaceful, but in winter it became a torrent, breaking its banks and bringing floods to the low ground at its junction with the mighty Nore. It separated the church of Saint Canice and its surrounding settlement, Kilkenny, from the higher ground and the Norman castle to the south. The Normans had lost no time in placing a fortress on a bluff dominating the crossing at a bend of the Nore. Stone castles became the backbone of their new colony. The Norman lighthouse at The Hook, where the Nore and its two sister rivers meet the sea, guided more and more settlers to Waterford and William the Marshal’s new port at Ross.

There was no deceit. By judicious marriage to Strongbow’s daughter, the Marshal gained sway over much of Leinster. By shrewd administration of the new laws, he nurtured the colony. He became the pre-eminent knight of his time. He might well have made himself a king, but he also was bound by his word, to the Plantagenets.

He acquired land by legal means, from the Bishop of Ossory, enabling him to lay out a town extending from the castle to the deceitful little river. He opened a quarry, providing free stone to the new settlers. He intended that they should stay. They paid him a rent of twelve pence, due at Easter and Michaelmas. He enabled the appointment of Hugh de Rous, the first Anglo-Norman Bishop of Ossory. Hugh also was a builder. He demolished the old Irish church and began to build a new cathedral. That work was to go on for over a hundred years. The old Kilkenny became Irishtown, while the new settlement appropriated the name to itself. The friars, both Grey and Black, came there to safeguard the souls of the citizens. In 1207 William the Marshal, pleased with his work, granted a charter to Kilkenny, a mere thirty-eight years after those Norman adventurers clambered to the safety of that windy headland in south Wexford.

In 1275 the Irish chiefs offered a grant of seven thousand marks to King Edward I, asking him to extend equality under English law to all of Ireland. This was long overdue. He needed the money, but he was wary of deceit. He had inherited a deep distrust of the Irish, his reluctant subjects.

Two years later Walter le Kyteler, a prosperous banker from Flanders, moved his family and wealth to a thriving Kilkenny, in search of further profit. His wife marked the momentous occasion by presenting him with a strong and healthy daughter. They called her Alice.

As a precursor to the cruelties of that terrible century, the trial for witchcraft in 1324 of Alice le Kyteler and her maid, Petronilla de Midia, introduced a new horror to Ireland. Their story still haunts the stone-flagged streets and narrow lanes of that ancient town beside the gliding Nore.

ONE

Thure Deum altissimum

auro regem et dominum

sed mirra mortis gremium.

(Incense to God on high; gold to king and lord, but myrrh to Death’s cold embrace.)

—Richard de Ledrede

HER FATHER always walked with a staff, a long stick cut from the fork of a blackthorn. The stump of the thicker branch formed a knob, polished now by years of handling. The staff reached almost to his shoulder and when he stopped to deliver himself of some observation, he leaned his right forearm on the knob, bending slightly forward, with his left thumb hooked into his belt.

Alice was always amused by his stance. He looked like a labouring man resting a moment on his spade, drawing breath, before bowing again to the stubborn soil. But those long, blue-veined hands had never handled spade or mattock. Mottled with age, they sped over the lines of the counting-table and bundles of tally sticks. They stacked and sorted coin of every denomination, mostly the Easterling silver he loved so well. They held invisible reins on many lives in Hightown and Irishtown and far beyond the encircling walls.

He liked to walk for a time during each day, maybe as far as the Great Bridge or the castle, feeling the pulse of the town, taking the greetings of the people in the street with a gracious nod. He knew their thoughts and fears and they knew that he read them well, these people of the Middle Nation. The inhabitants of the walled town feared their lord and his laws, even though he spent years away from them in England and France. They feared the lord’s seneschal with his armed men. Also they feared the wild men outside the walls, the barbarous Irish of the hills, a people detestable to all civilized men and to God Himself. Beyond lay the great world and outer darkness, where the Enemy of Mankind prowled ceaselessly, seeking to drag them down to eternal fire and damnation. Their only hope was in God, His Son and His Holy Mother, but the way to God was steep and beset with many pitfalls. God’s servants took their dues and tithes and eked out salvation at a price, just as Walter le Kyteler lent out his silver coin and took his interest twice a year on the feasts of blessed Hilary and holy Michael.

‘Why are you not damned for usury, like the Jews?’ Alice asked.

‘Ah,’ he replied, scratching his straggling beard, ‘because I am not a usurer. Like the Temple Knights, I charge no interest. The sin is in the interest. I charge a percentage for the service. The Jews are damned anyway for many crimes, but true Christians are entitled to a wage for their services.’

‘This is sophistry and you know it,’ she retorted. ‘Are you not afraid for your soul?’

Walter cleared his throat and spat into the dust. He pointed his staff at the great bulk of the cathedral looming over Irishtown.

‘That holy place was built for the glory of God, but every mason, every artificer, the ingeniator himself, was paid a wage. Every stone was paid for by service, or by silver and a portion of that silver trickled down from the hill and through my door.’

He chuckled. ‘They need me, you see, and others like me. When the time comes I shall purchase Masses and my bones will lie safely inside those walls. I shall leave money after me to protect you and my seed forever.’

He swept the tip of his staff in the dust. ‘I sweep it towards my door, just for luck. All the wealth of Kilkenny town lies in the dust, the stone, the dung, the soil and the work of the people. I ask only for my share.’

Alice looked up at the cathedral. The clouds fled across the summer sky, making the massive building appear to move. The high east gable rose above the narrow street like the prow of a great ship. The round bell tower, left over from a former age, appeared to lean as if it might totter onto the small, half-timbered houses below. She let him talk. He could be ponderous and sententious, but she humoured him by drawing him out. In return, he indulged his strong-willed and often wilful nineteen-year-old daughter, his only child. He gave her reading and the mathematics. Especially the mathematics. She would inherit his property and his creditors. He admired her insatiable curiosity about life and the world and sometimes he feared for her. The only security for his ‘bele Aliz’ would lie in money and a firm husband. That, however, was a matter for another day. He leaned on his staff, looking up, with his head to one side.

‘Every stone,’ he mused. ‘Even the long-legged king needs his Flemings and his Jews. Without us he could not keep his throne.’ She shushed him, putting her finger to her lips.

‘Be quiet,’ she said urgently. ‘You never know who might be listening.’

He laughed again, softly.

‘Where I grew up in Flanders the merchants built a great hall. They trade their wool and their fine linen there. The bankers set up their benches there.’

He paused, remembering the smell of lanolin, the odour of fresh linen and the chink of coin. He had fallen in love with the hubbub of the commerce reverberating in the vaulted chambers of the Cloth Hall.

‘When the spire is finished it will be taller than the cathedral.’

He paused, letting the point sink in.

‘Is that not tempting the vengeance of God?’ she wondered. ‘Will He not strike down such a challenge?’

‘No, they are good neighbours. Mutual interest, you see. Anyway the cats take all the blame and the bad luck with them.’

‘The cats?’ She knew the story already, but he would tell it.

‘Yes, the cats. Every year the merchants hurl cats from the four corners of the tower. The cats carry with them all the sin and any evil that lies in trade.’

Involuntarily he looked up, measuring the distance from the top of the tower to the street below. In his mind’s eye he saw cats flying through the air, twisting and flailing as they hurtled downwards to smash their nine lives in one bloody impact on the granite cobblestones. There were always one or two to be finished off by the clogs of the laughing onlookers.

Except for Lucifer. ‘Lucifer’, because he also was cast out and fell from Heaven. Walter had found him under a stall. A pang of pity prompted him to take the broken creature and carry it home, hidden under his coat. He concealed the cat in an outhouse and nursed it back to a semblance of health, although Lucifer’s nightly excursions were forever curtailed by a crippled leg. Walter said nothing to his parents, knowing that they would not permit bad luck to be brought over their threshold. As time went by, Lucifer assumed a proprietorial air in the stable yard and fathered many offspring who earned their lodging by keeping the mice in check. The name lived on in Lucifer’s son and grandson. When Walter le Kyteler secured safe conduct from the English king to bring his money to Ireland, along with his family and retainers, he had no more devoted a follower than Lucifer, the third generation to bear the name.

Walter straightened up and grasped his staff.

‘We must return to our toil, daughter,’ he declared, setting off purposefully up the sloping street towards the Watergate. Alice followed briskly, stepping fastidiously over ruts, outcropping stones and dung. The smell of the tanners’ vats gave way to the odours of the fish market and the shambles. She reflected that even if she were blindfolded, she could find her way around the town and its environs by mapping its many smells, from the sweet air of the tenter fields to the abbey mill and bakehouse or the communal privy and dunghill by the river. Every smell, in its own way, was the smell of money.

They crossed over the little bridge at the Watergate. She looked into the rushing stream, as it carried its tribute of water to the parent Nore, just below the abbey weir. The guard at the gate saluted as they passed from the Bishop’s town into that of the lord of the castle. The guard knew his betters, but all the same, he looked after Alice with a rueful glance. He liked the way her costly gown swirled as she walked. He liked how her girdle emphasized her small and graceful waist and how her dark hair peeped from beneath her hood. Not for me, he thought, rubbing the back of his forefinger over the stubble of his upper lip. Not for me, but as they say, a cat can look at a king. He sniffed. He scratched his armpit, where the leather jerkin chafed him in the summer heat. The river sang below the bridge.

Although there was an outstanding harvest that year and there was peace on the marches, the Irish found cause to fight among themselves. The feuding families of the north, south and west continued their incessant wars, but at least this left the towns of the east in peace, to consolidate their holdings and expand their trade with England. Ruling with a firm hand, the Norman lords played one petty princeling against another, assisting here, making punitive raids elsewhere, using English law when it suited and exacting fines under the Irish system, the laws of the Brehons, when it seemed more advantageous. This was not a stratagem open to the Irish. Their attempts to bribe the hard-pressed king and his justiciar in Dublin had not had the desired result. At rowdy parliaments the barons of the Middle Nation protected their exclusivity. The rot would set in if the ‘Hibernici servilis conditionis’ were ever to gain the privileges won by hard conquest and maintained by constant vigilance.

Alice had heard all the arguments many times. She turned half an ear to her uncle Guillaume’s rasping voice and her father’s persuasive tones. She enjoyed these exchanges, logic pitted against bombast, but on that day she delighted in the new flour and fresh bread in July, a rare occurrence. She rolled the dough, turning the lump in upon itself, pushing her knuckles into it, sprinkling flour to stop it sticking to the board. Her arms were white to the elbow. She set a small piece aside for the next batch, always a pinch of the ancestral yeast to carry on the line. There were those who regarded this as magic.

She wished that she could see into the seeds of every thing. There must be an explanation for it all. She had always asked ‘Why?’ Charming enough in a small child, but irritating in an adult and, at times, even dangerous.

‘Because that’s the way it is,’ her father would say. ‘There are laws binding everything. There are things we should not enquire about.’

She knew that the seasons came and went; that the dome of the sky with all its many lights revolved over the disc of the world; that the swallows that twittered all summer under the eaves, spattering the patch of paving with their droppings, would leave when the winter began to advance from the north, shortening the days and bringing cold, stinging rain and sleet. But why?

‘I’ll tell you why,’ bellowed Guillaume in the inner room. She heard his fist on the table. He was a man who would maintain standards. No longer a mere Fleming and certainly not an Englishman, he had become in his own mind one of the conquering Normans, with all their suspicion of those they had dispossessed. He mangled the French language on a daily basis, but after a few drinks, the truculent Fleming emerged again. Guillaume would have been more at home on foot in a Flemish phalanx, but he saw himself as one of the noble knights, even though they were, as often as not, unhorsed by the long and lethal halberds of the infantry.

‘Because there are too many Irish skulking inside our borders and too many of our own people willing to tolerate them.’

She knew where he was going with this argument. She knew the two corpses that hung from the gallows on Gibbetmede. She saw them frequently, scarecrows turning in the wind and blackened by time. She knew their mocking grins and eyeless sockets. Even in death, in typically Irish style, they laughed at the humour of their predicament. Their long straggling hair, hanging down over the brow, ‘a perfect haircut for a thief’, as Guillaume declared all too frequently, had been thinned out by carrion birds to thatch their high, swaying nests. The plight of the two thieves was hopeless, but still a cause for mirth.

Guillaume and his servants had caught them in the act of taking stock from Outer Farm. It was the most natural thing to them. In a few hours they would have been in the hills, lost in the straggling woods and mountain bogs. They laughed at Guillaume and put up their hands in surrender. They gibbered at him in the Irish tongue, but he would have none of that nonsense.

In the castle court they explained, through a clerk learned in their barbarous speech, that they were merely carrying on the trade of their ancestors. They offered to pay a fine. They smiled innocently at the seneschal, but now they would smile into eternity.

Guillaume was proud of his achievement. If only other people did their duty, the king’s people would be safe in their houses. He called for more ale. Alice wished that he would go. She knew that her father found his brother exhausting.

He referred to his brother as a corner boy. Guillaume de Ypres was a natural brawler. Ypres stood on a crossroads of trading routes. Guillaume had fought with French, Burgundians, English and the followers of the Count of Flanders. He had seen the ebb and flow of war, but eventually he had come with Walter to Ireland to make his fortune. Everything would be well as soon as the Irish were extirpated from English lands and left to exterminate one other. The sooner the better.

She sighed and wiped her floury hands. She brought the pitcher of ale into the inner room. She refilled the tankards. Her father caught her eye and smiled. He raised one conspiratorial eyebrow. Guillaume held out his tankard for her to pour. He perspired and breathed heavily, adjusting his weight to a more comfortable position, settling in for the evening. The third man, William Outlawe, regarded her closely. She filled his tankard. He thanked her graciously, watching her face as she poured.

William Outlawe, despite his name, was a quiet-spoken man in his middle years. Like Walter, he was a banker of considerable wealth, a good friend and frequent fellow investor. He owned a fine stone house not far from the Coal Market, with a long burgage plot stretching down to the river.

Alice knew his orchard and garden well. She had loved to go there as a child and look over the low wall at the dark waters of the Nore. She watched the frogs coupling, almost inert, in the green slimy waters of the New Quay, a narrow slot of slack water, cut between two gardens. She fished their spawn into a pail and waited for weeks to see the tiny black spots sprouting tails and then, wonder of wonders, arms and legs, even toes and fingers. But why?

Once, on a golden autumn day when she was very small, she had stepped out onto the level surface, a pavement of tiny weeds. She remembered the terror of the green pavement yielding beneath her feet and the rank smell of stagnant water. Her fingers clutched the soft mud of the bottom. Even in the depths of the green darkness she heard a shout. She could still feel William Outlawe’s strong hand on her collar, pulling her up into the air. She bawled with the shock. Her summer gown was smeared with black mud. Swags of weed hung from her hair and shoulders. She spluttered the vile-smelling water from her lips and bawled again. Her father was speechless, trying to hide his laughter, but William comforted her, wiping the mud and tears from her face. He gave her to his young wife to be cleaned up and wrapped in warm towels. He plucked a peach and gave it to her to take the taste away. She blinked away her tears and looked at the sun, at the blue sky and the high, white clouds. It was good to be alive and not lying with the frogs in the cold and fetid darkness.

Her father carried her home, holding her safe and warm in a heavy woollen shawl. He felt guilty for laughing and anxious to make light of the incident.

‘At least, my love, we know that you are no witch,’ he said, patting her gently.

‘Why?’ she asked, inevitably.

‘Because if you were a witch, you would not have gone under.’

She pondered this for a while.

‘Why?’

‘It’s all silly nonsense. There are no witches in the real world. Only in tales to frighten children.’

Despite her experience, she still loved the house of William Outlawe. She went there to see the cot men bringing fish into the narrow dock. They paddled small, crude boats dug from a single log. The boats were laden with nets and fish. They brought salmon and trout, char and eels, lampreys, whatever the river condescended to give up in each season. They grumbled about the castle weir and its fish traps and those of the monasteries downriver. Throughout the winter and into Lent they brought casks of salted herring from Ross, balanced precariously in their little bobbing cots. The tide carried them to Innistioge, but after that came the cursed portages around the weirs and mill races.

‘Allecia for la bele Aliz,’ said a fisherman, lifting a cask of herring onto the dock. His companions sniggered. She wondered about that, figuring that they shared some coarse joke at her expense. She resolved to find out and punish them.

If I were a real witch, she thought, I could bring storms and floods and sweep them all out to sea. I could destroy their nets and starve their families. But these things are not possible. Better to give these Irish churls a wider berth, avoid their smirks and false gallantry. Better in fact, to do as her father wished, to marry the wealthy and recently widowed William and then charge those fishermen through the nose to unload at her dock.

She looked at the three men seated by the window. Guillaume had lapsed into a contemplative silence. He held his tankard in his enormous paw. Occasionally he grumbled or belched. ‘Yes, indeed,’ he said several times, to nobody in particular.

William sat quietly, drawing wet circles with his tankard, on a small side table. She noted his elegant, yet restrained garb, a short coat trimmed with vair, and wide fashionable sleeves. His shoes were soft and pointed, of the best cordovan leather. His greying temples were lit by a shaft of sunlight through the leaded glass. His neck was somewhat slack and wrinkled. He was getting old, but his elegance compensated. He seemed absorbed in his thoughts.

Walter looked at her again and raised his eyebrow. She smiled a little smile. ‘Yes, indeed,’ she said. He raised his tankard to her in a silent toast.

TWO

Dies ista gaudij.

Dies leticie.

(This day of joy and happiness.)

—Richard de Ledrede

A STAKE WAS set up in the market-place, a great beam set into a pit of stone and mortar. Nothing would shift it, not even a bear. William spared no cost in making his wedding a memorable event. Butts of ale were hoisted on trestles. His servants poured for all who wanted it. Even the seneschal, Sir Arnaud le Poer, and his lady Agnes, graced the assembly, seated on a high tapestry-covered wagon. The tapestry depicted a hunting scene, a tribute to Sir Arnaud, renowned for his hunting of both men and the beasts of the forest.

Arnaud le Poer, seneschal of the palatine counties of Kilkenny and Carlow, lord of Gras Castle, Croghan, Moytober, Kenles and others too numerous to mention, was a figure to be reckoned with. In English they punned on his name. He was the personification of Power. He epitomized the men who kept the peace and guarded the marches against enemy incursions. He smiled upon William and his new bride.

The bear’s cage was manhandled into the circle. The crowd cheered and surged forward to gaze at the monster. The bear roared. The people fell back in fear. Small boys with dirty faces tripped over the feet of those behind them. The chain linking the gyves on the animal’s hind paws rattled against the bars. The keeper drew the loose end of the chain out under the door. Henry the Smith, proud of his skill, picked a glowing rivet from his brazier and strode into the circle, holding it aloft in his tongs. The crowd cheered his dexterity. With a few blows of his hammer he shackled the chain to an iron ring at the base of the stake. He stood back and bowed with a flourish. The people admired his muscular arms and his panache. The keeper unbarred the door. The bear lumbered forth.

The crowd fell silent, masters and apprentices, friars and good-wives, urchins and nobles, cripples and men at arms, all waiting in fear and glee to see some sport. The bear lunged to the length of the chain. The people flinched again, cringing from the enraged creature. Nothing like it had ever been seen before. The shackle held. Their courage returned.

The bear stood upright. He looked around at the faces. He raised his forepaws, as if in benediction. The people laughed. Then the dogs were loosed, mastiffs and baying hounds, bulldogs and yapping terriers. There arose a crescendo of barking and snarling, to the cheers of the crowd, when the bear eviscerated a hound or sent a yelping terrier flying through the air with a swipe of his bloody claw. Blood, foam and snot spattered the dusty street. Sometimes a dog fastened mighty jaws around the bear’s leg, flailing and snarling as the monster shook him off or tore him to pieces. Sometimes the bear fell on all fours, surging this way and that, wreaking havoc among his assailants, blood pumping from the many gashes in his limbs and face. It was the most magnificent spectacle of courage and strength that anyone had ever witnessed, a fitting accompaniment to the union of two of the most important families in the town.

The circle was strewn with broken and dying dogs. The survivors were called or beaten off and dragged away, to the mockery of the onlookers. Money changed hands and arguments flared. The keeper and some helpers used poles and lances to urge the bear back into the safety of his cage. Henry struck off the shackle and the door was barred again. The crowd cheered.

Sir Arnaud stood and shook hands with William. Walter looked around in satisfaction. Guillaume, red-faced from the heat and too much wine, applauded a fellow brawler. In high good humour, he slapped William’s son, Ivo, on the back. The boy scowled and hung his head. Alice, in her lustrous wedding clothes, looked at the stake with its iron ring. She saw the blood and the viscera of the broken dogs. She saw the crowd scattering to the ale butts and other diversions. She felt the hairs rising on the back of her neck. A cold shiver of dread prickled all over her body. The houses swayed before her eyes. She hesitated. Sir Arnaud offered his arm and conducted her to her wedding feast.

The harvests were good. Parliament underscored the peace. Attacks on the Irish at peace with the king were expressly forbidden, but still, no true subjects of the king might style their hair in the notorious culan, that drooping frond of hair that concealed a man’s eyes and thereby his intentions. Highways were cleared and bridges repaired. A curb was put on the keeping of idle men, kerns and hobbelars surplus to requirements.

Moreover, it was a good year for money. The king forbade the introduction of bad monies, pollards and crockards into Ireland. He threatened a revival of the custom of castration and amputation of the right hand, for those uttering debased coinage. Only sterlings of the king’s coinage might circulate throughout his realm. He forbade increases in wages. He brought stability at last.

Alain Cordouanier was glad of the peace. Although careful to stick to the main roads and to travel in company, it enabled him to wander in search of a better life. As a free man and a master craftsman he could follow any impulse and rise in the world, if God willed it. He could yoke his little horse to his cart and go.

The splendour of the scene brought him to a halt. He turned to his wife, Helene, and to his daughter, where they sat together on their little cart.

‘Look,’ he said. ‘Is it not magnificent? Are you not glad that I brought you here?’

The town glowed in an autumn sunset. The river mirrored the sky, broken only by the curving line of the castle weir and a straggle of willow and osier along its banks. The dark reflection of the mighty castle stood in the glassy water above the weir. All below was a tumble of white. The houses sent up a haze of blue smoke, out of which rose the spires of churches, James and John, Mary and the Magdalene. From the height they could just make out, above the trees, the bulk of the cathedral, a blur of violet against the sunset.

‘Oh, it is beautiful,’ she replied, slipping down and tucking her hand into his elbow. ‘Petra, what do you think?’ Petra jumped eagerly down from her perch. She leaned on the low stone wall. She looked down into the river. She smiled.

‘It is like the city of God that I have heard of in church. A city of gold.’

They loved the innocent joy of her twelve years. They loved her vivacity and gentleness, her beauty and instinctive delight in God’s creation. She was the treasure that they laid up against old age, the reason why Alain toiled and Helene cared for them so well.

They had not cared for Dublin. It was, said Alain, a city of footpads and filth, of nightwalkers and guerriers who would cut your throat for a penny. Even the watchmen refused to stir abroad at night, for fear of dogs and men of evil intent. Better than Dublin and better than the low, grovelling towns and villages of Meath, where he had begun his life, was this glowing town on the great river Nore.

‘I can see from your poor beast, that you have travelled a long way,’ said a voice behind them. They turned from their contemplation of the sunset, to see a young man, a Greyfriar, regarding them with interest. He spoke the heavily accented English of south Leinster. He patted Adam’s little horse, a superannuated hobby, not much more than a pony. The horse tore at the lush grass by the roadside, with a soft, rending sound. It shook its ears at the swirling midges. Alain noticed the friar’s worn and dusty sandals.

‘We have indeed, reverend sir,’ he replied ‘but now I think our journey has come to an end.’

‘Very good,’ said the friar, ‘but have you made provision for lodgings for the night?’ Alain shrugged. ‘Surely we will find somewhere in the town.’

‘But of course, and it will be my pleasure to conduct you to our abbey, where all Christian people may find a welcome.’

Alain looked at Helene. She seemed relieved. This was a good start.

‘We are grateful, reverend sir,’ he said, bowing his head. ‘In truth the journey has fatigued us greatly.’

‘I am Friar John,’ replied the friar, pushing back his cowl. ‘I have finished my pastoral work for the day and would be happy to walk along with you and hear the news of the country. I like to record everything that I hear, so that the race of Adam will remember.’

‘I go by the name of Alain Cordouanier.’

‘Well now,’ smiled the friar. ‘A useful man to have around. There will be plenty of work for you in Kilkenny, I have no doubt. Let us walk down by the Great Bridge and you will see our abbey across the river.’

Friar John liked to talk. It was a reaction, he said, to the long hours of silence enjoined upon his community. He liked to write also. He showed them his ink-stained fingers. ‘Rian ár gcoda, as the Irish say. The mark of our kind. Impossible to remove.’ He was nonetheless proud of the stain. ‘I am not permitted to write my own opinions.’ He spread his hands in a Gallic gesture of helplessness. ‘Of which I confess, I have many. Facts, Father Prior insists. Only facts. Too many opinions can stray into error and heresy. And you know where that can lead to.’ He assumed a serious mien.

Alain twisted the reins securely in his right hand. The horse clopped gently along. The harness creaked.

‘We have few opinions, Friar John. We have our work and our prayers. We are content to listen to those who know better.’

‘Very wise, very wise,’ nodded the friar, with a gravity that sat uneasily on his young and cheerful features. ‘Our great teacher, Roger, the doctor mirabilis, has shown us the dangers of error. Error is an instrument of the Evil One.’ He crossed himself at the name.

‘I know nothing of that,’ said Alain lightly, lifting the mood. ‘We are not lettered people. We will accept what you tell us. You are obviously a learned man.’

The friar shrugged. ‘It is my task in life. I teach the truth and I record the facts as faithfully as I can, but the funny thing …’ He frowned. ‘The funny thing is, Roger himself spent much of his life in prison for heresy and error.’

‘Perhaps,’ suggested Alain, ‘he knew too much. Where I come from we learn enough words and enough skill to put bread on the table. Perhaps your great teacher went astray in himself with too much knowledge.’

The friar put his head to one side, turning the idea over in his mind.

‘I never thought of it like that. Maybe he did. He was lucky to avoid the stake.’ He shrugged again and pointed across the river to the abbey. It stretched like a village along the western bank, a spired church and arched cloisters, a tower, low sunlight glinting on fish ponds and orchards, a white weir and the abbey mills. Alain, Helene and Petra gazed in admiration. The friar smiled proudly.

‘We own nothing and yet we are rich. Rich enough to serve God and his people in the right way. Roger disputed this wealth in poverty, but little good it did him. However, we must hurry now or the gate will be closed.’

They crossed the Great Bridge and entered into Irishtown.

‘Welcome to Dublin,’ said the guard genially. Alain looked at him in surprise.

‘Take no notice of him,’ said the friar. ‘Herebert likes his foolish joke.’

The guard laughed. ‘You will be late for vespers, my brother, and then there will be penance.’ He waved them on.

‘There is no harm in him,’ confided the friar. ‘He is the Bishop’s man, but he likes to remind people that the Bishop holds his power from Dublin. All Church lands are under Dublin law.’

‘Strange,’ said Alain. ‘I will never understand these matters.’

‘Sooth pley, quaad pley, as my friend Walter says,’ murmured the friar.

‘What is that?’ Alain frowned.

‘A true joke is a bad joke. Walter is a Fleming. Some day there will be strife between the Bishop and Dublin. Maybe not this bishop, but some day.’

Petra watched birds swooping about the cathedral tower. Their evening squawking filled the air.

They lodged that night in the guest house, warm and well fed. It was their first night under a roof for many weeks. They were inclined to whisper, in awe of the silence all about.

A bell rang for Compline. Petra lay in the darkness, listening to the distant voices chanting in unison. They sang in Latin, ‘nunc dimittis’, the Canticle of Simeon, an old man who had lived to see salvation. She knew no Latin. The voices rose and fell as the wind gusted. She found it comforting, the sound of safety and security, of voices echoing in darkness, entrusting themselves to God.

In the stillness before dawn Alice heard the chink, chink of the bell calling friars to prayer. She knew that they prayed, ‘Let us then cast off the work of darkness and put on the armour of light.’ What was that work of darkness? For the friars it was merely sleep. There was an old song, ‘Hey how the chevaldoures woke all night’, like the hum of flying beetles in the soft autumn darkness. Little golden horses with iridescent wings, flying wherever they wished, swooping over the moonlit river, making love under the over-hanging willows. Perhaps that was the work of darkness.

She listened. She heard a soft ‘thud’ on the roof, Lucifer returning from some night-time expedition. He seemed to levitate from rooftop to rooftop. There was silence and then another ‘thud’ and a scramble of claws on slate. She wondered what he would bring for her, a field mouse, a vole, a tattered bird lying cold on the doorstep.

It amused her that Lucifer had decamped from her father’s house and followed her to her new home. William’s dogs gave him a wide berth, fearing his needle-sharp teeth and flashing claws, but his devotion to Alice was total. Sometimes he came in by her bedroom window, a dark shape flowing through a half-opened casement, to curl up at her feet with a deep, vibrating purr.

William hated the cat. He would rise from the bed in his long night shirt and take Lucifer by the scruff of the neck.

‘Get out, get out,’ he would say, swearing under his breath as he opened the door. Sometimes he stubbed a toe against a chair in the darkness or stopped to relieve himself with a groan into a jordan. He was not quite the figure of fashion in his long shirt. His arms were thin and white, protruding from the sleeves like peeled elder sticks. In the half-light of dawn there was a white stubble on his usually clean-shaven chin.

‘Infernal beast,’ he grumbled, pulling back the drapery around the bed. He climbed in and, wrapping the blankets around himself, he turned his back. Soon he was asleep again and snoring, while Alice, feeling the early morning chill, attempted to retrieve some blanket for herself. She looked up at the rafters and drifted into a dream.

She rode with Sir Arnaud and his retinue over the hills of Muckalee. They galloped through forests and over high moorland. The horns sounded, echoing in the frosty wind. The stag led them on, until darkness enfolded them and they came to a lonely castle. The gate was open. They entered the bawn, the horses milling about in the darkness. A feast was prepared in the hall. Braziers glowed with warm, red coals. They drank wine. They spoke only in French, a glittering assembly of noble knights. Sir Arnaud laid her down on a bear-skin robe before a fire. He leaned over her, his dark eyes glinting like rain-washed coal.

She awoke, thwarted by the sound of birds and the tickle of what might have been a flea or even a spider. She had heard once that spiders drink from the eyes of sleepers.

She blinked and scratched the spot. She could not retrieve her dream. She was awake. Thoughts of the day intruded, Sir Arnaud, his voice, his touch, his smile, far away in one of his many manors, perhaps even in England with his liege lord and the king. Her skin crawled at the thought of lice. She would gather some wild larkspur and make a tincture. Lark’s heel, lark’s toe. It went by many names; lark’s claw, royal knight’s spur. Her mother had known all these names and had taught her something of the lore of herbs and flowers. Royal knight’s spur. She heard the clinking of his armour and the jingle of harness.

William turned and farted, an old man’s fart, careless of any who might hear it. He mumbled in his sleep. She sat up and looked at him in the dawn light. He was a mild and generous man, making few demands on her and granting whatever she asked for. At her request he had sent his son, Ivo, to the household of Guillaume, to learn about hard work and something of the profession of arms. ‘To put some backbone into him,’ she had suggested, but mainly to remove his surly presence from her household. In the house of Guillaume le Kyteler he would learn to drink and bellow and with a little luck, might fall and break his neck in some clumsy country tournament.

She knew that she had new life stirring inside her. It was something of a wonder, given that William was not greatly interested in the pleasures of the bed. She had imagined that a man twice her age, with a young and lusty wife, noticed by all the men of Hightown and beyond, might have luxuriated in his good fortune, storing up carnal delight before old age shrivelled him up like an empty husk. But no. William was measured and courteous when he came to her, brief in his lovemaking and she knew that all was done when he groaned, ‘O Jhesu! Jhesu!’ and fell back exhausted. Where was the soaring ecstasy, the blazing union of …?

There was that flea again. She lifted the sheet carefully. There he was, humping his way across the broad, white expanse of her nightdress. He stopped as if deep in thought. She moved to capture him, to feel the satisfying click of an enemy extinguished between fingernail and thumbnail, but he knew her mind. He toyed with her for a moment, feigning ignorance of the approaching finger and then he sprang. He vanished. She wondered how. It was a kind of magic. How might he come to earth again without dashing himself to pieces?

It was a foolish speculation. She knew that she would get him some time. She slipped from the bed and sat pondering the day. She thought that she might go to the abbey to be shriven of the lustful thoughts brought on by her dream. She would ask for Friar John, newly ordained and innocent of the world. She would tell him of her sinful lust and how her body reacted every time Sir Arnaud came into her thoughts. She would ask for his advice and watch him squirm in an agony of embarrassment. She would kneel before him and implore his blessing. She would look up at him with wide, tearful eyes. He would make the Sign of the Cross over her and flee from the room. She could crush him between finger and thumb if she wished. She smiled at her power, but still she liked Friar John. She liked his cheerful kindness and his love of knowledge. She had seen the manuscripts he copied and had heard him discuss his annals with her father. She would not destroy Friar John for sport. Not yet anyway.

‘I see,’ said Walter, drumming his fingertips on the table. ‘You require a loan to secure a place to set up in trade.’

‘My friend is a master cordwainer,’ interjected Friar John.

‘A cobbler,’ said Walter.

‘No, good sir,’ Alain put in. ‘A master cordwainer, not a cobbler.’

‘I see.’ Walter conceded the difference. ‘Why therefore are you wandering the country? Should you not have a workshop and apprentices?’

‘He has come to our town to find a peaceful place for his family,’ said the friar.

‘Hmm, and how do I know that you will not wander off again and leave me at the loss of my money? Have you anything that you might place with me as an earnest of good faith?’ Walter looked from Alain to the friar and back again.

Alain held out his hands, palms upwards.

‘Do you see these callouses? I have my skill and my good name. I have the safety of my wife and child in these hands. I have the bones of Saint Hugh. Your money will be safe with me.’

Walter looked to Alice where she stood by the window. She could see Alain’s pony and cart with a woman and a child standing by it. It was a pretty child with long fair hair.

‘What do you think, Alice?’ asked Walter with the ghost of a smile. ‘Should we risk our silver on this cordwainer? Does he strike you as a steady man?’

Alice turned from the window. She dropped a demure curtsey to Friar John. The friar blushed. He felt the heat rising even to his ears.

‘I think you should, Father. Our soles are always in need of protection in this rough world. Is that not so, Friar John?’

The friar mumbled in some confusion.

‘Well it is done, then,’ said Walter expansively. ‘I have a premises, albeit outside the walls, which should suit your purposes. It lies just beyond the Great Bridge, but convenient to the town and the tanners. Your family should be comfortable there.’ He extended his hand. ‘The good friar will direct you and if it proves satisfactory, come to me in the morning and we can draw up the indenture.’

He liked Alain’s firm handshake. He brought them to the door. He spoke to Helene and patted the child on the head. He returned to the room, pleased with the transaction.

‘What did he mean about the bones?’ Alice had been puzzling about it as she watched the family departing.

‘Saint Hugh. He was a shoemaker and a Christian martyr. The Emperor had him crucified like our Blessed Saviour. He forbade his companions to take the body from the cross and over time, his bones fell to the ground.’

‘So our friend carries relics of the saint. Very strange.’ Alice frowned.

‘No, not quite. Hugh’s companions gathered up the bones and made them into shoemaker’s tools. Every shoemaker carries the bones of Saint Hugh.’

‘I see,’ said Alice thoughtfully. ‘The power of the saint lies in the tools.’

‘More so in the hands that wield them,’ replied her father absently. He picked up a tally stick of soft poplar wood and began to write on it with a quill. The ink blurred in the soft grain. He wrote on one half and then repeated everything on the other half. He drew a jagged line across the centre and looked at his work with an air of satisfaction.

THREE

Cruore nam rubente – in carne fulgida

Tolluntur nostra mente – patrata scelera.

(By crimson blood our consciences are cleansed of sin.)

—Richard de Ledrede

BROTHER FERGAL LOVED his work. For almost seventy years he had lived in the abbey, the last of the Irish friars to survive the great changes. He was no threat to the English king in his possession of his Irish lands. Neither was he a threat to the great men of the order in their wisdom and piety. He just loved to tend the gardens and the orchards, to sing in his cracked voice of the glory of God and to mix the inks for the clever calligraphers of the scriptorium. His understanding of the written word was not great, but he knew that books contained power to triumph over time, to preserve the truth against all vicissitudes.

But the clever men could not work without ink. That was his particular skill. He made sturdy workaday black, by grinding charcoal so small that he could not feel the grains between finger and thumb. He bound it with rainwater and Arabian gum. It served well enough, but it tended to flow down the sloping parchment and form little feet at the base of each letter. He always smiled at the idea of the words dancing in little black shoes, tapping out their hidden meanings to a piper’s tune. For grander work he gathered oak galls in the woods outside the walls. Oak apples, people called them, but they contained no nourishment. Each gall was pierced by a pin hole, where a tiny wasp had escaped from his dark cradle. Did the creature know, wondered Fergal, what a contribution it had unwittingly made to learning? In the great days of Outremer, before the Holy Land was taken back by the heathens, the best oak apples came from Aleppo. All very fine, but in those days he had no excuse to wander in the autumn woods, kicking through leaf mould, listening to the wild creatures and the rushing of the wind. He had known those woods as a boy. He had poached the lord’s rabbits, in fear of his life. He recalled the sweet smell of a blown thrush’s egg and the early morning thrill of new mushrooms.

He ground the galls as fine as the charcoal. He infused them in wine and let them sit for a few days. Then he added the sal mortis, brought all the way from Moorish Spain. Finally, drop by drop, he added the obedient Arabian gum. He stirred the mixture carefully with a fig stick, always a fig stick, from the orchard of the lady Alice, and strained it into the ink-horns of the learned men.