Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

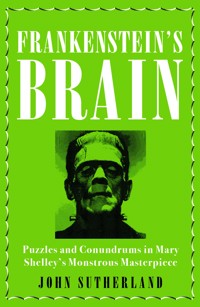

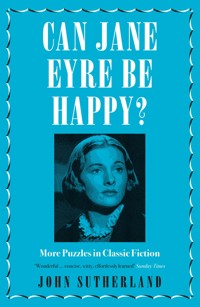

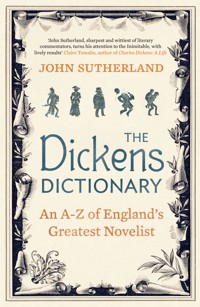

For fans new and old, an enjoyable tour through the world of Dickens in the hands of a master critic. Charles Dickens, the 'Great Inimitable', created a riotous fictional world that still lives and breathes for thousands of readers today. But how much do we really know about the dazzling imagination that brought all this into being? For the bicentenary of Dickens' birth, Victorian literature expert John Sutherland has created a gloriously wide-ranging alphabetical companion to Dickens' work, excavating the hidden links between his characters, themes, and preoccupations, and the minutiae of his endlessly inventive wordplay. Covering America, Bastards, Childhood, Christmas, Empire, Fog, Larks, London, Madness, Murder, Orphans, Pubs, Punishment, Smells, Spontaneous Combustion and Zoo to name but a few - John Sutherland gives us a uniquely personal guide to the great man's work. Excerpt: HANDS; Every Dickens novel has a master image. In Our Mutual Friend it is the river. In Bleak House it is the fog. In Little Dorrit, it is the prison. In Great Expectations it is the hand. We often know much more about the principals' hands in that novel than their faces. Who, when the name Magwitch is mentioned, does not think of those murderous 'large brown veinous hands'? Jaggers? One's nose twitches---scented soap (the lawyer, like Pontius Pilate, is forever washing his hands). Miss Havisham? Withered claws. So it goes on...

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 231

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Previously published in the UK in 2012 by

Icon Books Ltd, Omnibus Business Centre,

39–41 North Road, London N7 9DP

email: [email protected]

www.iconbooks.co.uk

This electronic edition published in the UK in 2012 by Icon Books Ltd

ISBN: 978-1-84831-392-7 (ePub format)

ISBN: 978-1-84831-393-4 (Adobe ebook format)

Printed edition (ISBN: 978-184831-391-0)

Sold in the UK, Europe, South Africa and Asia

by Faber & Faber Ltd, Bloomsbury House,

74–77 Great Russell Street,

London WC1B 3DA or their agents

Printed edition distributed in the UK, Europe, South Africa and Asia

by TBS Ltd, TBS Distribution Centre, Colchester Road,

Frating Green, Colchester CO7 7DW

Printed edition published in Australia in 2012

by Allen & Unwin Pty Ltd,

PO Box 8500, 83 Alexander Street,

Crows Nest, NSW 2065

Text copyright © 2012 Icon Books Ltd

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, or by any means, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Typeset in Minion by Marie Doherty

About the author

John Sutherland is the recently retired Lord Northcliffe Professor Emeritus at University College London: a title that one feels Dickens might have had some fun with. He has taught and published widely, particularly on Victorian fiction. His most recent relevant books are The Longman Companion to Victorian Fiction (Longman, 2009) and Lives of the Novelists: A History of Fiction in 294 Lives (Profile, 2011). He and Stephen Fender published Love, Sex, Death and Words: Surprising Tales from a Year in Literature with Icon Books in 2010.

In Memoriam

K.J. Fielding

Contents

Title page

Copyright

About the author

In Memoriam

Preface

Amuthement

Architectooralooral

Art

Baby Farming

Back-Stories

Bastards

Bedding

Blade or Rope?

Blind Spots

Bloomerism

Blue Death

Blue Plaques

Bohemians

Book Reading

Bookshop or Bookstall?

Boz

Busted Boiler

Candles

Cane

Cannibalism

Carlylism

Catholicism

Cats

Cauls

Charity

Cheap Dickens

Cheek

Child Abuse

Children

Christmas

Circumlocution

Compeyson’s Hat

Courvoisier (1.)

Courvoisier (2.)

Darwin

Dead Babies

Dogs

Dust

Dwarfs

Elastic Time

Englishman’s Castle

Fagins

Farewells

Fat Boy

Fishers of Men

Fog

Fragments

Gamp

Gruel

Hands

Hanged Man

Hanged Turkey

Hearts

Home for the Homeless

Horseman

Hue and Cry

Incest

Inimitable

Insomnia

Irishlessness

Itch Ward

Keynotes

Killer

King Charles’s Head

Madame Guillotine

Marshalsea

Megalosaurus

Merrikins

Micawberomics

Mist

Murder

Nomenclature

Ohm’s Law

Onions

Peckham Conjectures

Perambulation

Pies

Piplick

Poetryless

Pubs

Punishment

Rats

Ravens

Resurrection

Sausages

Secrets

Serialisation

Smells

Spontaneous Combustion

Streaky Bacon

Street-Sweepings

Svengali

Teeth

Thames (1. Death and Rebirth)

Thames (2. Pauper’s Graveyard)

Thames (3. Corruption)

Tics

Trains

Warmint

Zoo Horrors

Preface

2012 will be a year memorable for a British diamond jubilee, a British Olympic Games, and the commemoration of the country’s greatest novelist. How best to approach Charles Dickens? There may be readers who, like the boa-constrictor and the goat, can swallow Dickens whole. I personally have known only three: Philip Collins (who taught me as an undergraduate), K.J. Fielding (who supervised my PhD) and Michael Slater (a colleague at the University of London).

I admire the work of these scholars and I have used it (gratefully). But it seems to me that there is another approach, and one that is more appropriate to that peculiarity of the Dickensian genius: its infinite variety and downright oddness. When I think of Dickens I do not see a literary monument, but an Old Curiosity Shop, stuffed with surprising things: what the Germans call a Wunderkammer – a chamber of wonders.

This book, taking as its starting point 100 words with a particular Dickensian flavour and relevance, is a tour round the curiosities, from the persistent smudged fingerprint picked up in the blacking factory in which Dickens suffered as a little boy to the nightmares he suffered from his unwise visit at feeding time to the snake-room of London Zoo.

One of the wonderful things about this wonderful author is that, like Shakespeare, there can never be any final ‘explanations’, or ‘readings’. Merely an inexhaustible fund of entertainment or, as Sleary the circus master (see the first entry) would call it, ‘amuthement’. The ‘Great Entertainer’ one Gradgrindian critic (F.R. Leavis) called him, intending belittlement. I see it as a term of the highest literary praise.

Dickens will sell more copies of his fiction in 2012 than he did in any year of his life and – I would bet – any year since his death. To pick up any of his novels, and turn any of the pages, is to understand why. He entertains. So, I hope, will what follows.

John Sutherland

January 2012

Amuthement

In Hard Times the lisping circus-owner Sleary repeats, like a parrot with Tourette’s syndrome (an epidemic condition in Dickens’s fiction), his rule of life: ‘People mutht be amuthed.’ Sleary, in terms of his narrative presence, is very much a peripheral figure, but on the subject of the human need for something other than pedagogic instruction he has full Dickensian authority.

Hard Times is what the Victorians called a ‘Social Problem Novel’, centred on the wholly unamusing Preston mill-workers’ strike of 1854. Dickens locates Preston’s social problem as originating in what Carlyle called ‘cash nexus’: the belief that the only bond between mill-owner and mill-hand was the money that passed between them. This hard-nosed hard-headedness (hard-heartedness?) Dickens associated with the Manchester school of economics – Utilitarianism.

Economists scorn Dickens’s amateurish grasp of their dismal science. But where ‘amuthement’ was concerned he was expert. Utilitarianism, he felt, was anti-life. It did to human existence what maps do to landscape. It’s exemplified in Bitzer’s disintegrated definition of a horse (he’s the prize-pupil in Thomas Gradgrind’s school).

Quadruped. Graminivorous. Forty teeth, namely twenty-four grinders, four eye-teeth, and twelve incisive. Sheds coat in the spring; in marshy countries, sheds hoofs, too. Hoofs hard, but requiring to be shod with iron. Age known by marks in mouth.

The 1850s, when Dickens serialised Hard Times in his weekly paper, Household Words, saw an explosion in the travelling circus. They specialised in clever canines and trick equestrianism – the original horse and pony show. The big ones might even have elephants. Dickens alludes to the wondrous jumbo in his description of the great factory in Preston (‘Coketown’) ‘where the piston of the steam-engine worked monotonously up and down, like the head of an elephant in a state of melancholy madness’. How, one shudderingly wonders, would Bitzer describe that quadruped?

Hard Times opens in a schoolroom with Gradgrind laying down his educational theory: ‘Now, what I want is, Facts. Teach these boys and girls nothing but Facts. Facts alone are wanted in life.’ To which Dickens responds: ‘What about Fiction?’

Mr Gradgrind objects sternly to the circus.

A few months before the great strike, Manchester opened the country’s first free public library. But what to put in it? The utilitarian authorities decreed Gradgrindish ‘factuality’. No, insisted Dickens. Fiction should also feature prominently on those library shelves (he, too, was a trade-unionist of kinds: just like those mill-workers). His plea was borne out by the first statistics (Manchester loved what Cissy Jupe calls ‘stutterings’). The most popular book borrowed from the library was The Arabian Nights. Dickens refers to it frequently in his novel.

Point proved by Sinbad the Sailor and Jumbo the Pachyderm. People mutht be amuthed. But it would, alas, be some years before the Manchester Public Library stocked the work of that most amusing of writers, Boz.

Architectooralooral

Every reader of Great Expectations laughs at the above malapropism. Joe Gargery, the blacksmith with muscles of iron and a heart of gold, has come up to London – his first visit, we apprehend. He calls on Pip, now well on the way to becoming an arrant snob. ‘Have you seen anything of London, yet?’ asks Pip’s housemate, Herbert. ‘Why, yes, Sir’, replies Joe,

‘me and Wopsle went off straight to look at the Blacking Ware’us. But we didn’t find that it come up to its likeness in the red bills at the shop doors; which I meantersay,’ added Joe, in an explanatory manner, ‘as it is there drawd too architectooralooral.’

This is not Warren’s boot-blacking factory by Hungerford Stairs where the twelve-year-old Charles was put to work while his father was in debtors’ prison, but the imposing Day and Martin establishment at 97 High Holborn. It was not the first sight a tourist on his first trip to London – even one as ingenuous as Joe Gargery – would seek out. The coded reference is clear enough. Great Expectations is an autobiographical novel and this is a sliver of raw autobiography.

Hungerford Stairs, where the young Dickens suffered.

During his lifetime Dickens told only his designated biographer, John Forster, about his blacking factory ordeal as a child. But it pleased him to slip in sly references in his fiction. In Nicholas Nickleby there is a passing reference to a ‘sickly bedridden hump-backed boy’, whose only pleasure is ‘some hyacinths blossoming in old blacking bottles’. The ‘Warren’ figures centrally in Barnaby Rudge. Most direct is the description of the Grinby and Quinion factory in his other autobiographical novel, David Copperfield:

It was a crazy old house with a wharf of its own, abutting on the water when the tide was in, and on the mud when the tide was out, and literally overrun with rats. Its panelled rooms, discoloured with the dirt and smoke of a hundred years, I dare say; its decaying floors and staircase; the squeaking and scuffling of the old grey rats down in the cellars; and the dirt and rottenness of the place; are things, not of many years ago, in my mind, but of the present instant. They are all before me, just as they were in the evil hour when I went among them for the first time, with my trembling hand in Mr Quinion’s.

Dickens also never forgot. Warren’s blacking is no longer available in the shops, but for those who look carefully there is a trembling black fingerprint smudging every page he wrote.

Art

Dickens lived through a revolutionary period of art in Britain and Europe. Across the Channel, Impressionism re-imagined the visible world. The American artist, Whistler, threw his paint pot in the face of the British public – and went to court against art critic John Ruskin to justify the act. Ruskin himself fathered the most revolutionary home-grown movement, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.

Dickens was – viewed from one angle – an artistic impresario. Ever since ousting the luckless Robert Seymour from the Pickwick Papers (and turning down a hopeful young W.M. Thackeray as not a good enough draughtsman) he instructed a series of leading artists exactly how they should illustrate the Dickens texts. All his monthly series had two full-page etchings on steel and an illustrated wrapper. His later serials featured woodcuts and new lithographic technologies.

The roll call of artists who worked for (not with) Dickens is impressive: George Cruikshank, Hablot Knight Browne, Luke Fildes, George Cattermole, Daniel Maclise, Clarkson Stanfield, Richard Doyle, Samuel Williams, Samuel Palmer.

Dickens’s initial preference was for the light-fingered cartoon/sketch, as practised by Cruikshank. In his later career he favoured ‘dark plates’ – static and realistic. Luke Fildes’s ‘veritable photographs’ (as Dickens called them) for Edwin Drood represent the endpoint of the journey from the Cruikshankery of Oliver Twist.

Luke Fildes, from The Mystery of Edwin Drood, 1870.

Dickens, scholars have argued, actually and literally saw the world differently at the end of his life. Photography had made a new reality.

Dickens’s dictates to his artists (none of whom were munificently paid) were underpinned by conventional taste verging on prejudice. He wrote nothing more alarmingly prejudiced, critically, than his hysterical assault on John Millais’ early Pre-Raphaelite masterpiece, ‘Christ in the House of his Parents’, as it was exhibited in the Royal Academy in summer 1850:

You behold the interior of a carpenter’s shop. In the foreground of that carpenter’s shop is a hideous, wry-necked, blubbering, red-headed boy, in a bed-gown, who appears to have received a poke in the hand, from the stick of another boy with whom he has been playing in an adjacent gutter, and to be holding it up for the contemplation of a kneeling woman, so horrible in her ugliness, that (supposing it were possible for any human creature to exist for a moment with that dislocated throat) she would stand out from the rest of the company as a Monster, in the vilest cabaret in France, or the lowest ginshop in England.

It’s a grotesque outbreak of Podsnappery in a man whose judgement, in virtually everything of any importance, was normally so sound. When it came to art, Dickens was that awful English thing – ‘the man who knew what he liked’.

Baby Farming

Few great writers have been less interested in tilling the soil than Dickens. There was, however, one kind of farming that excited his interest – baby farming. It seems on the face of it a Swiftian fantasy of the Modest Proposal kind. But baby-farming was big business in the early 1840s.

During the cholera epidemic of 1849 (see ‘Blue Death’) there was death everywhere in London, but on total extinction level at the Drouet Establishment for Pauper Children in Tooting. The institution had been set up in 1825, as a dump for the metropolis’ unowned offspring.

By law they had to be looked after by the London authorities until they were fourteen – when the workhouse opened its uncharitable doors to them unless, like Oliver Twist, they could be farmed out again as pseudo-apprentices (many of the girls went straight into prostitution). Education, or any preparation for life, in the farm was virtually non-existent.

There were some 1,400 inmates at Drouet’s establishment in 1849 yielding four shillings and sixpence per head, per week, from public funds. They were crammed into accommodation worse than the black hole of Calcutta. Almost 200 died of cholera, over the half the children were infected.

A first inspection whitewashed Peter Drouet, the owner. It was bad air (‘atmospheric poison’) from London that was at fault. A second inspection, as the death rate soared, was highly critical. If there was indeed ‘atmospheric poison’ it was from the luckless children’s excrement, which made the inspectors retch. There was not a single case of cholera in Tooting (then green-field countryside), outside Drouet’s pest hole.

Dickens fired off four articles in his paper, Household Words. They burned with sarcastic indignation against ‘the Paradise in Tooting’. Following a series of damning inquests, Peter Drouet was brought to trial. A skilful defence team got him acquitted. The cholera was an act of God, the court determined.

One good thing came out of the trial. As Dickens concluded in his fourth article:

He [Drouet] was ‘affected to tears’ as he left the dock. It might be gratitude for his escape, or it might be grief that his occupation was put an end to. For no one doubts that the child-farming system is effectually broken up by this trial. And every one must rejoice that a trade which derived its profits from the deliberate torture and neglect of a class the most innocent on earth, as well as the most wretched and defenceless, can never on any pretence be resumed.

Dickens, baby-saver, can take some credit for that.

Back-Stories

With some principal characters in Dickens’s fiction we know the back-stories. With others, tantalisingly, we don’t. It’s not a small thing. In some novels – Bleak House notably – back-stories (those of Esther, Rouncewell, Lady Dedlock, Nemo) rise gradually to the surface and are the novel. What lies untold in the lives of other characters will baffle even readers of the most speculative cast of mind.

Great Expectations opens with Pip contemplating a family hecatomb. The gravestones of his mother, father, and five siblings record nothing but the fact of death. What wiped out the Pirrips? What did Pip’s father do for a living? Was his mother a gentle lady – or a shrew who lives on, shrewishly, in her daughter Mrs Joe?

There are further mysteries in the marriage of Mr and Mrs Joe. Why are she and Joe Gargery childless? It is not, as later events prove, sterility on his part: he and Biddy procreate soon enough. We can guess (without the slightest supporting evidence other than her extraordinary bitterness and those frightening pins in her apron) that she allows no conjugal liberties with her body. Why is she so angry at the world and her husband? It’s the more curious since she’s married to one of the nicest men ever to draw breath in Dickens’s fiction. Was she, like Miss Havisham (no mystery about that back-story) jilted at the altar?

Joe’s back-story we do know. He recounts it to Pip in some detail in Chapter 7. His brutal, drunken father ‘hammered’ him and his mother, ‘most onmerciful’. Nonetheless, Joe (blindly) insists that his father ‘was good in his hart’. Why did Joe – with this background – not grow up a drunken thug like his father? As the twig is bent, so the tree is bent. That, usually, is the law of Dickens’s universe. Joe, mysteriously, grows straight.

Magwitch recounts a very similar back-story to Joe’s, in Chapter 42, explaining to Pip how he was ‘hardened’ by childhood abuse into a criminal and a murderer. Doubtless Bill Sikes, the unspeakable brute in Oliver Twist, could have told the same tale. How has Joe contrived to preserve his softness?

There’s no clear answer. Dickens, we deduce, loved contraries as much as William Blake. He could adhere – in the case of Magwitch – to the view that, as William Godwin put it, ‘circumstances create crime’. He could simultaneously adhere to the quite opposite view that ‘good harts’ can rise above any circumstance. But not, alas, very often. There are more Sikeses than Joe Gargerys in Dickens’s world.

Bastards

Children born out of wedlock are as common as fleas in Dickens’s dramatis personae (16,000 characters make up the population of the Dickens world, it’s reckoned). Fagin’s little pickers and stealers are almost certainly illegitimate. At least half the sad enrolment of Dotheboys Hall in Nicholas Nickleby, one can plausibly assume, are legally unowned by any parent.

Three of Dickens’s novels, Oliver Twist, Barnaby Rudge and Bleak House, hinge on bastardy. In the hierarchy of unlucky children the illegitimate rank lower than orphans (like Pip) but higher than street urchins (like Jo in Bleak House). Bastards, in Dickens’s fictional universe, invariably discover their mysterious parentage – as, in melodramatic circumstances, do Oliver, Esther Summerson, Estella, and Hugh the Ostler.

Until the 1960s British law and society were cruelly prejudiced towards children born out of wedlock. They had no inheritance rights – not even to their father’s name (if known). The bastard carried an indelible stigma through life. What had they done to deserve it? They were born.

Dickens uses his bastardy McGuffin in different ways. Hugh in Barnaby Rudge is more brutal even than the horses whose droppings he shovels. He places himself at the head of the Gordon riots – wielding murderous axe and torch – only to discover, late in the day, that he is the offspring of Sir John Chester. As the rope goes round his own neck, Hugh curses ‘that man who in his conscience owns me for his son’.

Blue blood, Dickens argues, does not – as English society fools itself – make for ‘good breeding’. Oliver Twist makes a quite opposite point. ‘The old story’, sighs the workhouse attendant looking down at the ringless hand of the hero’s mother. But, bastard that he may be, Oliver has a gentility gene. Surely a parish boy brought up among the Mudfog riff-raff would say ‘Gissamore!’ not ‘Please, sir, I want some more’. By their accent may ye know them.

Esther in Bleak House makes a third point. Her ‘godmother’ (i.e. aunt – disinclined to own the relationship) tells her, by way of birthday present: ‘Your mother, Esther, is your disgrace, and you were hers.’ Nonetheless, as the novel progresses, no heroine in Dickens’s fiction reveals herself to be morally less disgraceful than Esther, Mr Jarndyce’s ‘Dame Durden’. Goodness is goodness – whatever is missing in the register of births, marriages, and deaths.

Two things are odd. Only once does the b-word itself intrude onto Dickens’s printed page, when the obnoxious Monks hurls the imprecation at his hated half-brother, Oliver Twist. The other oddity is that bastardy, as a Dickensian plot device, disappears from his pages around 1860.

Two explanations are offered. Most likely is that Dickens himself had a ‘love child’ (as he would not have called it) by Ellen Ternan, his mistress. The wilder speculation is that having separated from Mrs Dickens, mother of his ten legitimate children, he had an incestuously engendered child by his sister-in-law Georgina (in the imbroglio of the separation there were some ugly medical investigations to certify her virginity). A ring once belonging to a claimant of the ‘Dickens – bar sinister’ title was sold at auction in January 2009 for £9,000.

Ellen Ternan, ‘the invisible woman’.

Bedding

The bed is an important article in the Dickens world. The greater part of A Christmas Carol, for example, happens while Scrooge is lying in bed. No deathbeds are more famous than those of Little Nell and Paul Dombey.

Oliver Twist’s re-ascent to the station in life to which he belongs is marked by the beds he lies in. He is born on a ‘workus’ bed – a crude pallet, we assume, as his little body is wrenched, heartlessly, from the body of his dying mother. At Sowerberry’s, the undertaker, his bed is a straw mattress under the counter, alongside the coffins. In Fagin’s den he occupies one of the hessian sacks (sleeping bags of a kind) alongside his fellow thieves.

Finally, he rests on respectable linen after he is taken in by Brownlow. This, we apprehend, is where he should end up. So too should Fagin end up as in the Cruikshank illustration, sitting on his prison bunk: no sleep for the wicked on that punitive palliasse.

No rest for Fagin.

Dickens himself had idiosyncratic bed-rituals, designed to produce serene slumber. When travelling, he carried a pocket compass with him. This was for night-time use. He would insist that his bed for the night be placed so that the headboard faced due north. When he composed himself for sleep, Dickens would situate himself centrally within the bed by extending his arms full out, in a kind of crucifixion pose, so as to establish absolute equidistance from the two edges.

He was as particular about his final resting place as he was in life. He instructed in his will: ‘that my name be inscribed in plain English letters on my tomb. I rest my claims to the remembrance of my country upon my published works.’

Initially he was to be entombed at Rochester Cathedral (emblematised in the frontispiece to Edwin Drood). Public opinion, mobilised by The Times, insisted instead that Poets’ Corner in Westminster Abbey should be his final resting place. On 14 June he was interred in an empty cathedral (only an apostolic dozen mourners were admitted) under the plainest of headstones, which he had decreed.

In 1935 an attempt to have his body exhumed and returned to Rochester, where the town felt it belonged, was rejected. I have recently been to examine the Westminster memorial. His head, I am sad to say, does not, by my compass, point north. RIP, nonetheless, and sucks to Rochester.

Blade or Rope?

Dickens was always curious about the best way to kill people. People, that is, who deserved to be killed. He gave the question considerable thought in the 1840s. The central issue, as he put it in a newspaper article of 1845, was that

Society [has] arrived at that state, in which it spares bodily torture to the worst criminals: and [has] agreed, if criminals be put to Death at all, to kill them in the speediest way.

But what was the ‘speediest way’? He pondered the question during his family trip to Italy in the mid-1840s when, in Rome, he witnessed a beheading. The victim richly deserved the axe. He had waylaid a countess on pilgrimage, robbed her, before beating her to death with her own pilgrim’s staff.

Dickens observed the execution with a novelist’s eye, a tourist’s curiosity, an Englishman abroad’s prejudices, and a penal reformer’s interest. The condemned man was brought to the platform

bare-footed; his hands bound; and with the collar and neck of his shirt cut away, almost to the shoulder. A young man – six-and-twenty – vigorously made, and well-shaped. Face pale; small dark moustache; and dark brown hair … He immediately kneeled down, below the knife. His neck fitting into a hole, made for the purpose, in a cross plank, was shut down, by another plank above; exactly like the pillory. Immediately below him was a leathern bag. And into it his head rolled instantly.

The executioner was holding it by the hair, and walking with it round the scaffold, showing it to the people, before one quite knew that the knife had fallen heavily, and with a rattling sound.

Whatever else, those Italians did their bloody work with enviable ‘speed’. But importing their efficient blade into England was tricky. It was not English. And beheading was, traditionally, a privilege of aristocracy. It went against the populist grain to honour every criminal Tom, Dick and Harry with it. Whatever next? Silken hang ropes?

But how to get that necessary ‘speed’? Fagin, for example, would have dangled and strangled, dancing on the end of the rope for up to twenty minutes while the spectators laughed uproariously at his hilarious death-jig. No wonder Oliver faints.

British penology was as worried as Dickens and experimented with a variety of ‘drops’ and ‘knots’ to introduce the necessary ‘humanity’ (i.e. speed) with the traditional rope and gallows. By the time John Jasper (as we assume Dickens planned) meets his end in the unfinished Edwin Drood, there were no more public hangings. He would have had a ‘short drop’ of some seven feet, calculated by his body weight, and the side knot would have ‘speedily’ snapped his neck. Problems solved.

Italy solved it a different way by abolishing capital punishment in the 1860s. Mussolini brought it back.

Blind Spots

There are black holes in Dickens’s fiction that suck in speculation and emit no light. They are just there. He is, for example, the pre-eminent Victorian novelist who came to fame at almost the same moment that the young queen came to her throne. But can one find a single reference to Victoria in his Victorian fiction? Or to her 25th jubilee in Bleak House (compare, for example, with In the Year of Jubilee by Dickens’s disciple, George Gissing, commemorating the golden anniversary in 1887)? Kings and queens – even French kings and queens, in A Tale of Two Cities – are notable by their absence. Is the vacant space republicanism? Or a blind spot?

Dombey and Son came out at precisely the same period that the Irish potato famine was ravaging and depopulating that country. Dickens was immensely popular in Ireland. He had a distinguished disciple (some would say rival) in Charles Lever, the ‘Hibernian Boz’. But, for all the tears drawn for the destitute Jo the Sweeper in Bleak House, there is no glance across the Irish Sea at a calamity so horrific that it has been laid at England’s door as colonial genocide. Indifference? Or a blind spot?

It’s not a consistent blinkering. Dickens was very open-eyed about the Preston mill-workers’ strike in Hard Times. He even made a trip to Coketown (as he calls it) to get eye-witness evidence. No blind spot in that novel. Similarly in Little Dorrit (specifically Chapter 10, on the Circumlocution Office) Dickens is wholly in tune with current anger at the bungling incompetence with which Whitehall had managed the Crimean War. No blind spot on that burning issue.

Opium figures frequently in Dickens’s fiction and forms the magnificent opening, in a drug den, of Edwin Drood. But Dickens, who was in full fictional flow in the late 1840s, makes no reference to the iniquitous Opium Wars, which enforced collective drug addiction on the whole Chinese people – in the interest of boosting the East India Company’s export revenues.

John Jasper wakes in the opium den.