Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

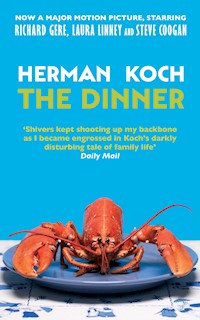

THE MILLION-COPY BESTSELLER THAT'S GOT EVERYONE TALKING... A summer's evening in Amsterdam and two couples meet at a fashionable restaurant. Between mouthfuls of food and over the delicate scraping of cutlery, the conversation remains a gentle hum of politeness - the banality of work, the triviality of holidays. But the empty words hide a terrible conflict and, with every forced smile and every new course, the knives are being sharpened... Each couple has a fifteen-year-old son. Together, the boys have committed a horrifying act, caught on camera, and their grainy images have been beamed into living rooms across the nation; despite a police manhunt, the boys remain unidentified - by everyone except their parents. As the dinner reaches its culinary climax, the conversation finally touches on their children and, as civility and friendship disintegrate, each couple shows just how far they are prepared to go to protect those they love. SHORTLISTED FOR THE NATIONAL BOOK AWARDS - INTERNATIONAL AUTHOR OF THE YEAR LONGLISTED FOR THE IMPAC DUBLIN LITERARY AWARDS 'A brilliantly addictive novel that wraps its hands around your throat on page one and doesn't let go' -- SJ Watson

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 388

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE DINNER

First published in the Netherlands in 2009 by Ambo Anthos, Amsterdam.

First published in Great Britain in 2012 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Herman Koch, 2009 Translation Copyright © Sam Garrett, 2012

The moral right of Herman Koch to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

The moral right of Sam Garrett to be identified as the translator of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

The publishers gratefully acknowledge the support of the Dutch Foundation for Literature.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination and not to be construed as real. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Trade Paperback ISBN: 978 1 84887 382 7

OME ISBN: 978 0 85789 720 6

E-Book ISBN: 978 1 84887 386 5

Atlantic Books An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd Ormond House 26–27 Boswell Street London WC1N 3JZwww.atlantic-books.co.uk

THE DINNER

CONTENTS

APERITIF

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

APPETIZER

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

MAIN COURSE

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

DESSERT

36

37

38

39

DIGESTIF

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

1

We were going out to dinner. I won’t say which restaurant, because next time it might be full of people who’ve come to see whether we’re there. Serge made the reservation. He’s always the one who arranges it, the reservation. This particular restaurant is one where you have to call three months in advance – or six, or eight, don’t ask me. Personally, I’d never want to know three months in advance where I’m going to eat on any given evening, but apparently some people don’t mind. A few centuries from now, when historians want to know what kind of crazies people were at the start of the twenty-first century, all they’ll have to do is look at the computer files of the so-called ‘top’ restaurants. That information is kept on file, I happen to know that. If Mr L was prepared to wait three months for a window seat last time, then this time he’ll wait for five months for a table beside the men’s room – that’s what restaurants call ‘customer relations management’.

Serge never reserves a table three months in advance. Serge makes the reservation on the day itself, he says he thinks of it as a sport. You have restaurants that reserve a table for people like Serge Lohman, and this restaurant happens to be one of them. One of many, I should say. It makes you wonder whether there isn’t one restaurant in the whole country where they don’t get faint right away when they hear the name Serge Lohman on the phone. He doesn’t make the call himself, of course, he lets his secretary or one of his assistants do that. ‘Don’t worry about it,’ he told me when I talked to him a few days ago. ‘They know me there, I can get us a table.’ All I’d asked was whether it wasn’t a good idea to call, in case they were full, and where we would go if they were. At the other end of the line, I thought I heard something like pity in his voice. I could almost see him shake his head. It was a sport.

There was one thing I didn’t feel like that evening. I didn’t feel like being there when the owner or on-duty manager greeted Serge Lohman as though he were an old friend; or seeing how the waitress would lead him to the nicest table on the side facing the garden, or how Serge would act as though he had it all coming to him, that deep down he was still an ordinary guy and that was why he felt entirely comfortable among other, ordinary people.

Which was precisely why I’d told him we would meet in the restaurant itself and not, as he’d suggested, at the café around the corner. It was a café where a lot of ordinary people went. How Serge Lohman would walk in there like a regular guy, with a grin that said that all those ordinary people should above all go on talking and act as though he wasn’t there – I didn’t feel like that, either.

2

The restaurant is only a few blocks from our house, so we walked. That also took us past the café where I hadn’t wanted to meet Serge. I had my arm around my wife’s waist, her hand was tucked somewhere inside my coat. The sign outside the café was lit with the warm, red and white colours of the brand of beer they had on tap.

‘We’re still too early,’ I said to my wife. ‘What I mean is: if we went to the restaurant now, we’d be right on time.’

My wife: I should stop calling her that. Her name is Claire. Her parents named her Marie Claire, but in time Claire didn’t feel like sharing her name with a magazine. Sometimes I call her Marie, just to tease her. But I rarely refer to her as my wife – on official occasions sometimes, or in sentences like ‘My wife can’t come to the phone right now,’ or ‘My wife is very sure she asked for a room with a sea view.’

On evenings like this, Claire and I make the most of the moments when it’s still just the two of us. Then it’s as though everything is still up for grabs, as though the dinner date was only a misunderstanding, as though it’s just the two of us out on the town. If I had to give a definition of happiness, it would be this: happiness needs nothing but itself, it doesn’t have to be validated. ‘All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way,’ is the opening sentence of Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina. All I could hope to add to that is that unhappy families – and within those families, in particular the unhappy husband and wife – can never get by on their own. The more validators the merrier. Unhappiness loves company. Unhappiness can’t stand silence – especially not the uneasy silence that settles in when it is all alone.

So when the bartender at the café put our beers down in front of us, Claire and I smiled at each other, in the knowledge that we would soon be spending an entire evening in the company of the Lohmans: in the knowledge that this was the finest moment of that evening, that from here on it would all be downhill.

I didn’t feel like going to the restaurant. I never do. A fixed appointment for the immediate future is the gates of hell, the actual evening is hell itself. It starts in front of the mirror in the morning: what you’re going to wear, and whether or not you’re going to shave. At times like these, after all, everything is a statement, a pair of torn and stained jeans as much as a neatly ironed shirt. If you don’t scrape off the day’s stubble, you were too lazy to shave; two days’ beard immediately makes them wonder whether this is some new look; three days or more is just a step from total dissolution. ‘Are you feeling all right? You’re not sick, are you?’ No matter what you do, you’re not free. You shave, but you’re not free. Shaving is a statement as well. Apparently you found this evening significant enough to go to the trouble of shaving, you see the others thinking – in fact, shaving already puts you behind 1–0.

And then I always have Claire to remind me that this isn’t an evening like every other. Claire is smarter than I am. I’m not saying that out of some half-baked feminist sentiment or in order to endear women to me. You’ll never hear me claim that ‘women in general’ are smarter than men. Or more sensitive, more intuitive, or that they are more ‘in touch with life’, or any of the other horseshit that, when all is said and done, so-called ‘sensitive’ men try to peddle more often than women themselves.

Claire just happens to be smarter than I am, I can honestly say that it took me a while to admit that. During our first years together I thought she was intelligent, I guess, but intelligent in the usual sense: precisely as intelligent, in fact, as you might expect my wife to be. After all, would I settle for a stupid woman for any longer than a month? In any case, Claire was intelligent enough for me to stay with her even after the first month. And now, almost twenty years later, that hasn’t changed.

So Claire is smarter than I am, but on evenings like this she still asks my opinion about what she should wear, which earrings, whether to wear her hair up or leave it down. For women, earrings are sort of what shaving is for men: the bigger the earrings, the more significant, the more festive, the evening. Claire has earrings for every occasion. Some people might say it’s not smart to be so insecure about what you wear. But that’s not how I see it. The stupid woman is the one who thinks she doesn’t need any help. What does a man know about things like that? the stupid woman thinks, and proceeds to make the wrong choice.

I’ve sometimes tried to imagine Babette asking Serge whether she’s wearing the right dress. Whether her hair isn’t too long. What Serge thinks of these shoes. The heels aren’t too flat, are they? Or maybe too high?

But whenever I do, I realize there’s something wrong with the picture, something that seems unimaginable. ‘No, it’s fine, it’s absolutely fine,’ I hear Serge say. But he’s not really paying attention, it doesn’t actually interest him, and besides: even if his wife were to wear the wrong dress, all the men would still turn their heads as she walked by. Everything looks good on her. So what’s she moaning about?

This wasn’t a hip café, the fashionable types didn’t come here – it wasn’t cool, Michel would say. Ordinary people were by far in the majority. Not the particularly young or the particularly old, in fact a little bit of everything all thrown together, but above all ordinary. The way a café should be.

It was crowded. We stood close together, beside the door to the men’s room. Claire was holding her beer in one hand, and with the fingers of the other she was gently squeezing my wrist.

‘I don’t know,’ she said, ‘but I’ve had the impression recently that Michel is acting strange. Well, not really strange, but different. Distant. Haven’t you noticed?’

‘Oh yeah?’ I said. ‘I guess it’s possible.’

I had to be careful not to look at Claire, we know each other too well for that, my eyes would give me away. Instead, I behaved as though I was looking around the café, as though I were deeply interested in the spectacle of ordinary people involved in lively conversation. I was relieved that I’d stuck to my guns, that we wouldn’t be meeting the Lohmans until we reached the restaurant; in my mind’s eye I could see Serge coming through the swinging doors, his grin encouraging the café regulars above all to go on with what they were doing and pay no attention to him.

‘He hasn’t said anything to you?’ Claire asked. ‘I mean, you two talk about other things. Do you think it might have something to do with a girl? Something he’d feel easier telling you about?’

Just then the door to the men’s room opened and we had to step to one side, pressed even closer together. I felt Claire’s beer glass clink against mine.

‘Do you think it has something to do with girls?’ she asked again.

If only that were true, I couldn’t help thinking. Something to do with girls … wouldn’t that be wonderful, wonderfully normal, the normal adolescent mess.

‘Can Chantal/Merel/Rose spend the night?’

‘Do her parents know? If Chantal’s/Merel’s/Rose’s parents think it’s okay, it’s okay with us. As long as you remember … as long as you’re careful when you … ah, you know what I mean, I don’t have to tell you about that any more. Right? Michel?’

Girls came to our house often enough, each one prettier than the next, they sat on the couch or at the kitchen table and greeted me politely when I came home.

‘Hello, Mr Lohman.’

‘You don’t have to call me Mr Lohman. Just call me Paul.’

And so they would call me ‘Paul’ a few times, but a couple of days later it would be back to ‘Mr Lohman’ again.

Sometimes I would get one of them on the phone, and while I asked if I could take a message for Michel, I would shut my eyes and try to connect the girl’s voice at the other end of the line (they rarely mentioned their names, just plunged right in: ‘Is Michel there?’) with a face. ‘No, that’s okay, Mr Lohman. It’s just that his cell phone is switched off, so I thought I’d try this number.’

A couple of times, when I came in unannounced, I’d had the impression that I’d caught them at something, Michel and Chantal/Merel/Rose: that they were watching The Fabulous Life on MTV less innocently than they wanted me to think: that they’d been fiddling with each other, that they’d rushed to straighten their clothes and hair when they heard me coming. Something about the flush on Michel’s cheeks – something heated, I told myself.

To be honest, though, I had no idea. Maybe nothing was going on at all, maybe all those pretty girls just saw my son as a good friend: a nice, rather handsome boy, someone they could show up with at a party – a boy they could trust, precisely because he wasn’t the kind who wanted to fiddle with them right away.

‘No, I don’t think it’s got anything to do with a girl,’ I said, looking Claire straight in the eye now. That’s the oppressive thing about happiness, the way everything is out on the table like an open book: if I avoided looking at her any longer, she’d know for sure that something was going on – with girls, or worse.

‘I think it’s more like something with school,’ I said. ‘He’s just done those exams, I think he’s tired. I think he underestimated it a little, how tough his sophomore year would be.’

Did that sound believable? And above all: did I look believable when I said it? Claire’s gaze shifted quickly back and forth between my right and my left eye; then she raised her hand to my shirt collar, as though there were something out of place there that could be dealt with now, so I wouldn’t look like an idiot when we got to the restaurant.

She smiled and placed the flat of her hand against my chest. I could feel two fingertips against my skin, right where the top button of my shirt was unbuttoned.

‘Maybe that’s it,’ she said. ‘I just think we both have to be careful that at a certain point he doesn’t stop talking about things. That we get used to that, I mean.’

‘No, of course. But at his age he kind of has a right to his own secrets. We shouldn’t try to find out everything about him, otherwise he might clam up altogether.’

I looked Claire in the eye. My wife, I thought at that moment. Why shouldn’t I call her my wife? My wife. I put my arm around her and pulled her close. Even if only for the duration of this evening. My wife and I, I said to myself. My wife and I would like to see the wine list.

‘What are you laughing about?’ Claire said. My wife said. I looked at our beer glasses. Mine was empty, hers was still three-quarters full. As usual. My wife didn’t drink as fast as I did, which was another reason why I loved her, this evening perhaps more than other evenings.

‘Nothing,’ I said. ‘I was thinking … I was thinking about us.’

It happened quickly: one moment I was looking at Claire, looking at my wife, probably with a loving gaze, or at least with a twinkle, and the next moment I felt a damp film slide down over my eyes.

Under no circumstances was she to notice anything strange about me, so I buried my face in her hair. I tightened my grip around her waist and sniffed: shampoo. Shampoo and something else, something warm – the smell of happiness, I thought.

What would this evening have been like if, no more than an hour ago, I had simply waited downstairs until it was time to go, rather than climb the stairs to Michel’s room?

What would the rest of our lives have been like?

Would the smell of happiness I inhaled from my wife’s hair still have smelled only like happiness, and not, as it did now, like some distant memory – like the smell of something you could lose just like that?

3

‘Michel?’

I was standing in the doorway to his room. He wasn’t there. But let’s not beat around the bush: I knew he wasn’t there. He was in the garden, fixing the back tyre of his bike.

I acted as though I hadn’t noticed that, I pretended I thought he was in his room.

‘Michel?’ I knocked on the door, which was half open. Claire was rummaging through the closets in our room; we would have to leave for the restaurant in less than an hour, and she was still hesitating between the black skirt with black boots or the black pants with the DKNY pumps.

‘Which earrings?’ she would ask me later. ‘These, or these?’ The little ones looked best on her, I would reply, with either the skirt or the pants.

Then I was in Michel’s room. I saw right away what I was looking for.

I want to stress the fact that I had never done anything like that before. Never. When Michel was chatting with his friends on the computer, I always stood beside him in such a way, with my back half turned towards the desk, that I couldn’t see the screen. I wanted him to be able to tell from my posture that I wasn’t spying or trying to peek over his shoulder at what he’d typed on the screen. Sometimes his cell phone made a noise like pan pipes, to announce a text message. He had a tendency to leave his cell phone lying around. I won’t deny that I was tempted to look at it sometimes, especially when he had gone out.

‘Who’s texting him? What did he/she write?’

One time I had even stood there with Michel’s cell phone in my hand, knowing that he wouldn’t be coming back from the gym for another hour, that he had simply forgotten it – that was his old phone, a Sony Ericsson without the slide: the display showed ‘1 new message’, beneath an envelope icon. ‘I don’t know what got into me; before I knew it, I had your cell phone in my hand and I was reading your message.’ Maybe no one would ever find out, but then again maybe they would. He wouldn’t say anything, but he would suspect me or his mother nonetheless; a fissure that, with the passing of time, would expand into a substantial chasm. Our life as a happy family would never be the same.

It was only a few steps to his desk in front of the window. If I leaned forward I would be able to see him in the garden, on the flagstone terrace in front of the kitchen door where he was fixing his inner tube – and if Michel looked up he would see his father standing at the window of his room.

I picked up his cell phone, a brand-new black Samsung, and slid it open. I didn’t know his pin code, if the phone was locked I wouldn’t be able to do a thing, but the screen lit up almost right away with a fuzzy photo of the Nike swoosh, probably taken from a piece of his own clothing: his shoes, or the black knitted cap he always wore, even at summertime temperatures and indoors, pulled down just above his eyes.

I scrolled down through the menu, which was roughly the same as the one on my own phone, a Samsung too, but six months old and therefore already hopelessly obsolete. I clicked on My Files and then on Videos. Sooner than expected, I found what I was looking for.

I looked and felt my head gradually grow cold. It was the sort of coldness you feel when you take too big a bite from an icecream cone or sip too greedily from an ice-cold drink.

The kind of coldness that hurt – from the inside out.

I looked again, and then I kept looking: there was more, I saw, but how much more was hard to say.

‘Dad?’

Michel’s voice came from downstairs, but then I heard him coming up the stairs. I snapped shut the slide on the phone and put it back on his desk.

‘Dad?’

It was too late to hurry into our bedroom, to take a shirt or jacket out of the closet and pose with it in front of the mirror; my only option was to come out of Michel’s own room as casually and believably as possible – as though I’d been looking for something.

As though I’d been looking for him.

‘Dad.’ He had stopped at the top of the stairs and was looking past me, into his room. Then he looked at me. He was wearing his Nike cap, his black iPod nano dangled from a cord at his chest and a set of headphones was slung around his neck; you had to give him credit, fashion and status didn’t interest him; after only a few weeks he had replaced the white earbuds with a standard set of headphones, because the sound was better.

Happy families are all alike: that popped into my mind for the first time that evening.

‘I was looking for …’ I began. ‘I was wondering where you were.’

Michel had almost died at birth. Even these days I often thought back on that blue, crumpled little body lying in the incubator just after the Caesarean: that he was here was nothing less than a gift, that was happiness too.

‘I was patching my tyre,’ he said. ‘That’s what I wanted to ask you. Do you know if we’ve got valves somewhere?’

‘Valves,’ I repeated. I’m not the kind of person who ever fixes a flat tyre, who would even consider it. But my son – in the face of all evidence – still believed in a different version of his father, a version who knew where the valves were.

‘What were you doing up here?’ he asked suddenly. ‘You said you were looking for me. Why were you looking for me?’

I looked at him, I looked into the clear eyes beneath the black cap, the honest eyes, which, I’d always told myself, formed a not-insignificant part of our happiness.

‘Oh, nothing,’ I said. ‘I was just looking for you.’

4

Of course they weren’t there yet.

Without revealing too much about the location, I can say that the restaurant was hidden from the street by a row of trees. We were half an hour late already, and as we crossed the gravel path to the entrance, lit on both sides by electric torches, my wife and I discussed the possibility that, for once, just this once, it might be us and not the Lohmans who arrived last.

‘Want to bet?’ I said.

‘Why should I?’ Claire said. ‘I’m telling you: they’re not there.’

A girl in a black T-shirt and black floor-length pinafore took our coats. Another girl, in the same black outfit, was flipping through the reservations book lying open on a lectern.

She was only pretending not to recognize the name Lohman, I saw, and pretending badly at that.

‘Lohman, was it?’ She raised an eyebrow and made no effort to hide her disappointment at the fact that it wasn’t Serge Lohman standing there in real life, but two people whose faces meant nothing to her.

I could have helped out by saying that Serge Lohman was on his way, but I didn’t.

The lectern-with-book was lit from above by a thin, copper-coloured reading lamp: Art Deco, or some other style that happened to be just in or just out of fashion at the moment. The girl’s hair, black as the T-shirt and pinafore, was tightly tied up at the back in a wispy ponytail, as though it too had been designed to fit in with the restaurant’s house style. The girl who had taken our coats wore her hair in the same tight ponytail. Perhaps it had something to do with regulations, I thought to myself, hygiene regulations, like surgical masks in an operating room: after all, this restaurant prided itself on serving ‘all-organic’ products – the meat came from actual animals, but only animals that had led ‘a good life’.

Across the top of the tight black hairdos, I glanced at the dining room – or at least at the first two or three visible tables. To the left of the entrance was the ‘open kitchen’. Something was being flambéed at that very moment, from the looks of it, accompanied by the obligatory clouds of blue smoke and dancing flames.

I didn’t feel like doing this at all, I realized again. My aversion to the evening that lay ahead had become almost physical – a slight feeling of nausea, clammy hands and the start of a headache somewhere behind my left eye – not quite enough, though, for me to actually become unwell or fall unconscious right there on the spot.

How would the black-pinafore girls react to a guest who collapsed before even getting past the lectern, I wondered. Would they try to haul me out of the way, drag me into the cloakroom – in any case, somewhere where the other guests couldn’t see me? They would probably prop me up on a stool behind the coat racks. Politely but firmly, they would ask whether they could call me a taxi. Off! Off with this man! – how wonderful it would be to let Serge stew, what a relief to be able to put a whole new twist on this evening.

I thought about what that would mean. We could go back to the café and order a plate of regular-person food, the daily special was ribs with fries, I’d seen on the blackboard above the bar. ‘Spare-ribs with fries €11.50’ – probably less than a tenth of what we’d have to cough up here, each.

Another alternative would be to head straight for home, with at the very most a little detour past the video shop for a DVD, which we could then watch on the TV in the bedroom, lying on our roomy double bed: a glass of wine, some crackers, a few types of cheese to go with (one more little detour past the all-night shop), and a perfect evening would be complete.

I would be entirely self-effacing, I promised myself, I would let Claire choose the film: even though that meant it was bound to be some costume drama. Pride and Prejudice, A Room with a View or something Murder on the Orient Express-ish. Yes, that was a possibility, I thought, I could pass out and we could go home. But instead I said: ‘Serge Lohman, the table close to the garden.’

The girl raised her eyes from the page.

‘But you’re not Mr Lohman,’ she said.

I cursed it all, right there: the restaurant, the girls in their black pinafores, this evening that was ruined even before it began – but most of all I cursed Serge, for this dinner he’d been so keen to arrange, a dinner for which he couldn’t summon up the common courtesy to arrive on time. The way he never arrived on time anywhere; people in union halls across the country had to wait for him to show up too, the oh-so-busy Serge Lohman was probably just running late; the meeting in the last union hall had run over and now he was caught in traffic somewhere; he didn’t drive himself, no, driving would be a waste of time for someone of Serge’s status, he had a chauffeur to do that for him, so he could spend his precious time judiciously, reading important documents.

‘Oh yes I am.’ I said. ‘Lohman is the name.’

I kept my eyes fixed on the girl, who actually blinked this time, and I opened my mouth for the next sentence. The moment had come to clinch the victory: but it was a victory that smacked of defeat.

‘I’m his brother,’ I said.

5

‘The aperitif of the house, which we’d like to offer you today, is pink champagne.’

The floor manager – or maître d’, or supervisor, the host, the head waiter, or whatever you call someone like that in restaurants like this – wasn’t wearing a black pinafore. He had a three-piece suit on. The suit was pale green with blue pinstripes, and sticking out of the breast pocket was a blue hanky. What they call a pocket square.

His voice was subdued – almost too subdued to be heard above the hubbub in the dining room; there was something weird about the acoustics in this place, we’d noticed that as soon as we sat down at our table (on the garden side! How did I guess!). If you didn’t speak up, your words drifted away, up to the glass ceiling, which was also much higher than normal for a restaurant. Ridiculously high, you might say, if you didn’t know that the height of the ceiling had everything to do with the building’s former use: a dairy, I thought I’d read somewhere, or a sewage disposal plant.

The floor manager stuck out his little finger and pointed at something on our table. At the tea-warmer, I thought at first – instead of a candle or two, all the tables here had a tea-warmer – but, no, the little finger was pointing out the plate of olives he had apparently just put there. In any case, I didn’t remember it having been there before, not when he’d pulled back our chairs. When had he put the olives on the table? I was struck by a brief but intense wave of panic. This was happening to me more often lately: suddenly pieces of the puzzle were gone – bites out of time, empty moments during which my thoughts must have been elsewhere.

‘These are Greek olives from the Peloponnese, lightly doused in first-pressing, extra-virgin olive oil from Sardinia, and polished off with rosemary from …’

The floor manager leaned over our table slightly as he spoke, but we could still barely hear him: in fact, the last part of the sentence became completely lost, leaving us in the dark as to the origin of the rosemary. Normally I don’t give a damn about that kind of information – as far as I cared the rosemary could have come from the Ruhr or the Ardennes, but it seemed like far too much fuss over one little plate of olives, and I had no intention of letting him off the hook that easily.

And then that pinkie. Why would anyone point with their pinkie? Was that supposed to be chic? Did it go with the suit with blue pinstripes, like the light-blue hanky? Or did he simply have something to hide? His other fingers, after all, were hidden the whole time; he kept them folded against the palm of his hand, out of sight – perhaps they were covered with flaky eczema or symptoms of some untreatable disease.

‘Polished off?’ I said.

‘Yes, polished off with rosemary. Polished off means that they—’

‘I know what it means,’ I said cuttingly – and perhaps a bit too loudly as well. A man and a woman at the next table stopped talking for a moment and looked over at us: a man with a beard that was much too big, covering his face almost entirely, and a woman a little too young for him, in her late twenties, I figured; his second wife, I thought, or maybe some piece of fluff he was trying to impress by taking her to a restaurant like this. ‘Polished off,’ I repeated a little more quietly. ‘I know that doesn’t mean that someone “polished off” the olives. As in “getting rid of them” or “blowing them away”.’

From the corner of my eye I saw that Claire had turned her head and was gazing out the window. Things were not off to a good start; the evening was already ruined, and there was no need for me to ruin it any further, especially not for my wife.

But then the manager did something I hadn’t expected: I had more or less counted on seeing his mouth fall open, his lower lip start to tremble and perhaps even the start of a blush, after which he would stammer some vague apology – something he’d been taught to rattle off, a protocol for dealing with rude and difficult guests – but instead he burst out laughing. What’s more, it was a real laugh, not a fake or polite laugh.

‘I’m sorry,’ he said, raising his hand to his mouth; the fingers were still curled up as they’d been when he pointed at the olives a minute ago, only the pinkie was sticking out. ‘I never thought about it like that.’

6

‘What’s with the suit?’ I asked Claire, after we had both said that we’d like the aperitif of the house and the floor manager had walked away from our table.

Claire raised her hand and brushed my cheek. ‘Sweetheart …’

‘No, listen, it’s weird, he’s wearing it for a reason, right? You’re not going to tell me that it’s not on purpose?’

My wife gave me a lovely smile, the smile she always bestowed on me when she thought I was getting worked up about nothing – a smile that so much as said that she found all the fuss entertaining at best, but that I mustn’t think for one second that she was going to take it seriously.

‘And then the tea-warmer,’ I said. ‘Why not a teddy bear? Why not hold a silent vigil?’

Claire took a Peloponnesian olive from the plate and put it in her mouth. ‘Mmm,’ she said. ‘Lovely. Too bad, though, you really can taste that the rosemary has had too little sunlight.’

Now it was my turn to smile; the rosemary, the manager had told us finally, was ‘home-grown’, from a glassed-in herbarium behind the restaurant. ‘Did you notice how he points with his pinkie all the time?’ I said, opening the menu.

What I was in fact planning to do was look at the prices of the entrées: the prices in restaurants like this always fascinate me. Let me make it clear right away that I’m not stingy by nature, that has nothing to do with it; I’m also not going to claim that money is no object, but I’m light years removed from people who say it’s a ‘waste of money’ to eat in a restaurant while ‘at home you can make things that are so much nicer’. No, people like that don’t understand anything, not about food and not about restaurants.

My fascination isn’t that kind of fascination; it has to do with what, for the sake of convenience, I’d call the yawning chasm between the dish itself and the price you have to pay for it: as though the two variables – money on one side, food on the other – have nothing to do with each other, as though they inhabit two separate worlds and have no business being side by side on the same menu.

That was what I was planning to do: I was going to read the names of the dishes, and then the prices that were printed next to them, but my eye was caught by something on the left-hand page.

I looked, looked again, then peered around the restaurant to see if I could spot the manager’s suit.

‘What is it?’ Claire asked.

‘Did you see what it says here?’

My wife looked at me questioningly.

‘It says: “Aperitif of the house, ten euros”.’

‘Oh?’

‘But that’s insane, isn’t it?’ I said. ‘The man said: “We’d like to offer you the aperitif of the house,” right? “The aperitif of the house is pink champagne.” So what are you supposed to think? You think they’re offering you the pink champagne, or am I nuts? If they offer you something, you get it, right? “Can we offer you the this-or-that of the house?” Then it doesn’t cost ten euros, it’s free!’

‘No, wait a minute, not always. If the menu says “steak à la maison”, steak of the house in other words, all it means is that it was prepared according to the recipe of the house. No, that’s not a good example … House wine! Wine of the house: that doesn’t mean you get the wine for free, does it?’

‘All right, okay, that’s obvious. But this is different. I hadn’t even looked at a menu yet. Someone in a three-piece suit pulls back your chair for you, puts down a lousy little plate of olives and then says something about offering you the aperitif of the house. That’s at least a little confusing, isn’t it? Then it sounds as though you’re getting it, not that you have to pay ten euros for it, right? Ten euros! Ten! Look at it this way: would we have ordered a small glass of bland pink champagne if we’d known that it cost ten euros?’

‘No.’

‘That’s what I’m saying. They trick you into it with that horseshit about the “aperitif of the house”.’

‘You’re right.’

I looked at my wife, but she looked back earnestly. ‘No, I’m not pulling your leg,’ she said. ‘You’re right. It really is different from steak à la maison or a house wine. It is weird. It’s almost like they do it on purpose, to see if you’ll fall for it.’

‘It is, isn’t it?’

In the distance I saw the three-piece suit flash by, into the open kitchen; I raised my hand and waved, but the only one who noticed was one of the black-pinafore girls. She hurried over to our table.

‘Listen here,’ I said, and as I held up the menu for the girl to see, I glanced over at Claire – for support, for affection, perhaps only for an understanding look; a look that said you couldn’t mess with the two of us, not when it came to so-called aperitifs of the house – but Claire’s eyes were fixed on something a long way behind me: at the entrance to the restaurant.

‘Here they come,’ she said.

7

Usually, Claire always sits facing the wall, but tonight we’d done it the other way around. ‘No, no, now it’s your turn for a change,’ I said when the manager pulled back our chairs and she moved automatically towards the seat that looked out only on the garden.

Usually, I’m the one who sits with my back to the garden (or the wall, or the open kitchen), for the simple reason that I want to be able to see everything. Claire lets me have my way. She knows I don’t like staring at walls or gardens, that I’d rather look at the people.

‘Come now,’ she said as the floor manager stood waiting politely, his hands on the back of the chair, the chair with a restaurant view that he had pulled back for my wife, as a matter of principle, ‘this is where you want to sit, isn’t it?’

It’s not that Claire goes out of her way to appease me. It’s just something she has inside her, a sort of inner calm or depth that makes her content with blank walls and open kitchens. Or, like here, with a few patches of grass between gravel paths, with a rectangular pond and a few low hedges outside a window that stretches from the glass ceiling all the way to the floor. There must have been trees out there too, somewhere, but the combination of falling darkness and reflecting glass made it impossible to tell.

That’s all she seems to need: that, and a view of my face.

‘Not tonight,’ I said. Tonight all I want to see is you, that’s what I was planning to add, but I couldn’t bring myself to say that out loud with the manager standing there in his pinstripes.

That evening all I wanted was to cling to my wife’s familiar face, but there was another, not unimportant reason for me to sit facing the garden: it meant I could allow my brother’s entrance to go unseen: the bustle at the door, the predictable grovelling of the manager and the pinafore girls, the other guests’ reactions – but when the moment finally came, I turned in my chair and looked anyway.

Everyone, of course, had noticed the Lohmans’ arrival. There was even what you might describe as a stifled tumult around the lectern: no less than three girls in black pinafores were fussing over Serge and Babette, the manager was hovering around the lectern too – and there was someone else there as well: a little man with bristly grey hair, dressed not in black from head to toe, but simply in jeans and a white turtleneck. The restaurant owner, I suspected.

Yes, it had to be the owner, for now he stepped forward to extend a personal welcome to Serge and Babette.

‘They know me there,’ Serge had told me a few days ago. He knew the man in the white turtleneck, a man who didn’t emerge from the open kitchen to shake hands with just anyone.

The guests, however, pretended not to notice; in a restaurant where you had to pay ten euros for the aperitif of the house, the rules of etiquette probably didn’t allow for an open display of recognition. They all seemed to lean a few fractions of an inch closer to their plates, all apparently doing their best at the same time to forge ahead with their conversations, to avoid falling silent, because the volume of the general hubbub increased audibly as well.

And while the manager (the white turtleneck had disappeared back into the kitchen) was escorting Serge and Babette past the tables, no more than a barely perceptible ripple ran across the restaurant: a breeze falling across the still-smooth surface of a pond, a breath of wind through a field of grain, no more than that.

Serge smiled broadly and rubbed his hands together, while Babette remained a few paces behind. Judging by the little steps she took, her heels were probably too high for her to keep up with him.

‘Claire!’ He spread his arms, my wife was already out of her chair and they were pecking each other three times on the cheek. There was nothing I could do but stand up: remaining seated would require too many explanations.

‘Babette …’ I said, taking my brother’s wife by the elbow.

In fact, I had counted on her turning her cheek towards me for the obligatory three kisses and then kissing the air beside my own cheek, but instead I felt the soft pressure of her mouth, first on my one cheek, then the other; the third and final time she pressed her lips, no, not exactly to my mouth, but right beside it. Dangerously close to my mouth, one might say. We looked at each other; she was wearing glasses, as usual, but they seemed different from the ones she’d been wearing last time. I, at least, couldn’t remember her glasses having such dark lenses.

Babette, as I mentioned earlier, is one of those women who look good in anything, including glasses. Yet there was something else, something different about her this time, like a room where someone has thrown out all the flowers while you were gone: a change in the interior you don’t even notice at first, not until you see the stems sticking out of the garbage.

To call my brother’s wife a ‘presence’ would be putting it mildly. There were men, I knew, who felt intimidated or even threatened by her figure. She wasn’t fat, no; fatness or thinness had very little to do with it, the proportions of her body were in perfect harmony. Everything about her, though, was big and broad: her hands, her feet, her head – too big and too broad, those men thought, and they went on to make insinuations about the size and breadth of other parts of her body, as if somehow to reduce the threat to human proportions.