Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

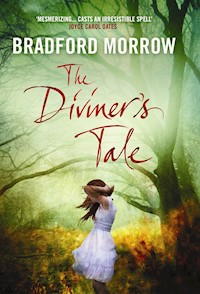

Cassandra Brooks is a single mother-of-two, schoolteacher and water diviner. Deep in the woods as she dowses the land for a property developer, she is confronted by the body of a young girl, swinging from a tree, hanged. When she returns with the authorities, the body has vanished. Already regarded as an eccentric, her story is disbelieved- until a girl turns up in the woods, alive, mute and identical to the girl in Cassandra's vision. In the days that follow, Cassandra's visions become darker and more frequent as they begin to take on a tangible form. Forced to confront a past she has tried to forget, Cassandra finds herself locked in a game of cat-and-mouse with a real life killer who has haunted her for longer than she can remember. At once an ingeniously plotted mystery and a magical love story, The Diviner's Tale will pull you helplessly down into Cassandra's luminous world.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 510

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Cassandra Brooks is a single mother-of-two, a schoolteacher and a water diviner. Deep in the woods as she dowses the land for a property developer, she is lost in her thoughts, until something catches her eye and her daydream shatters.

Swinging from a tree is the body of a young girl, hanged. But when she returns with the authorities, the body has vanished. Already regarded as the local eccentric, her story is disbelieved – until a girl turns up in the woods, alive, mute and identical to the girl in Cassandra’s vision.

In the days that follow, Cassandra’s visions become darker and more frequent as they begin to take on tangible form. Forced to confront a past she has tried to forget, Cassandra finds herself locked in a game of cat-and-mouse with a real life killer who has haunted her for longer than she can remember.

This spellbinding concoction of suspense, romance and the supernatural will pull you helplessly down into Cassandra’s luminous world.

Bradford Morrow is the author of numerous acclaimed works of fiction and poetry, including, recently, Ariel’s Crossing and Giovanni’s Gift. He is also the founder of the literary magazine Conjunctions, which he has edited since 1981. Winner of a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2007, and Professor of Literature at Bard University,

‘Bradford Morrow, like the diviner-heroine of The Diviner’s Tale, is a mesmerizing storyteller who casts an irresistible spell. He has constructed an ingeniously plotted mystery story that is at the same time a love story – luminous and magical, fraught with suspense, beautifully and subtly rendered – a feat of prose divination.’

JOYCE CAROL OATES, winner of the National Book Award

‘In his sublime new novel The Diviner’s Tale, Bradford Morrow accomplishes the deep, subtle miracle I have been waiting and waiting for someone to effect – he gives us the first novel-length work of fiction that actually does create a seamless breathing breathtaking unity of the literary and the suspense novel. This novel detonates the very notion of genre.’

PETER STRAUB, winner of the Bram Stoker Award

‘This haunting portrayal of a woman possessed by irresistible visions which draw her through mystery and terror to cataclysmic self-discovery is both chilling and impossible to put down. Morrow is at the top of his form: bold, original, and mesmerizing. Truly a stunning achievement.’

VALERIE MARTIN, winner of the Orange Prize

‘Superb. The only thing I did for two straight days was read this book — it really is that riveting... somehow alchemically able to combine suspense, wonder, and romance all in one seamless story that kept you guessing and gasping right up until the end.’

JONATHAN CARROLL, winner of the World Fantasy Award

‘Beautifully written and tautly paced... With the aptly named but thoroughly contemporary Cassandra as the book’s flawlessly rendered voice, Morrow has created a woman both heroic in what she seeks and human in what she finds. The Diviner’s Tale is about past crimes and future consequences, a tale whose subtle and mysterious confluences are as elusive as water underground.’

THOMAS H. COOK, winner of the Edgar Allan Poe Award

First published in the United States of America in 2011 by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

This edition first published in Great Britain in 2011 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Bradford Morrow 2011.

The moral right of Bradford Morrow to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This is a work of fiction. All characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-1-84887-570-8 (hardback) ISBN: 978-1-84887-571-5 (trade paperback) eBook ISBN: 978-0-85789-262-1

Printed in Great Britain.

Corvus An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd Ormond House

CONTENTS

Part I: DIVINING CASSANDRA

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 6

CHAPTER 7

Part II: IN SEARCH OF SANCTUARY

CHAPTER 8

CHAPTER 9

CHAPTER 10

CHAPTER 11

CHAPTER 12

CHAPTER 13

Part III: REVENANT IN THE LIGHT HOUSE

CHAPTER 14

CHAPTER 15

CHAPTER 16

CHAPTER 17

CHAPTER 18

CHAPTER 19

Part IV: WIDENING CIRCLE, TIGHTENING CIRCLE

CHAPTER 20

CHAPTER 21

CHAPTER 22

CHAPTER 23

CHAPTER 24

Part V: THE FIFTH TURNING

CHAPTER 25

CHAPTER 26

CHAPTER 27

CHAPTER 28

CHAPTER 29

CHAPTER 30

If a man could pass through Paradise in a Dream, &

have a Flower presented to him as a pledge that his Soul

had really been there, & found that Flower in his hand

when he awoke—Aye! And what then?

—SAMUEL TAYLOR COLERIDGE

Everyday life is only an illusion behind which lies the

reality of dreams.

—WERNER HERZOG

Part I

DIVINING CASSANDRA

1

MY FATHER, WHOM I trust as surely as yesterday happened and tomorrow might not, was the first to call me a witch. He meant it in a loving way, but he meant it. In later years, he’d sometimes say it with a defiant touch of pride. —My daughter, the witch.

I brought this on myself by warning my brother, Christopher, with all the raw certainty of a seven-year-old who believed she could see things hidden from others, not to go to the movies one August evening with his best friend, Ben. He laughed, like any older brother twice his sister’s age would, and said I could take a metaphysical flying leap. I can still picture him, lanky, loose-jointed, tall as a tree to my eyes, wearing his favorite faded baseball jersey untucked over a pair of worn jeans and scuffed brown boots. —Hey, Nutcracker, see you in the afterlife. Turning, he clomped down the porch stairs two steps at a time to the waiting car. I remember lying in long orchard grass in the field beyond our house, listening to the restless crickets scraping their bony legs together, and waiting for the meteors to tell me when the worst had come to pass.

At first the sky was calm. Just an infinity of cold stars and a few winking planets out in the void, carving their paths through the darkness. Maybe I got it wrong, I hoped. But then so many shooting stars started chasing across the night I couldn’t begin to know which of them had carried my beloved laughing brother away. The crickets stopped their chorus as the whole field sank into silence. I sat up and gasped. How I wished what I saw above me was a great black slate instead of a brilliant light show. Defeated by my vindication, I walked back to the house and sneaked in the side door.

—That you, Cass? my mother called out. My mother, who could hear a mouse yawn the next county over.

—No, I whispered, not wanting to be me anymore.

Christopher never came back. Neither did Ben or Ben’s father, Rich Gilchrist, who was the town supervisor. The funeral was attended by half a thousand people. That happens when you are a well-liked local politician and chief of the volunteer fire department. Not to mention a decorated war veteran. Many men in dress uniforms attended from all over Corinth County in rural upstate New York and across the Delaware into Pennsylvania. Phalanxes of fire trucks bright as polished mirrors lined the road beside the churchyard cemetery. People wept in the wake of all the eulogies, and afterward the bells tolled. It was the second big funeral in as many years—Emily Schaefer, Chris’s classmate, was killed the year before in what some believed was not the accidental death the authorities declared it—and our town still hadn’t recovered. Whereas before we followed one hearse to the cemetery, this year three coffins were carried out together after a joint service, one draped with an American flag and two smaller unadorned ones behind. To this day I can hear the bagpipes playing their dirge.

Family friends and Christopher’s inseparable band of buddies—Bibb, Jimmy, Lare, Charley Granger, my favorite, even the brooding Roy Skoler, who slipped out back to smoke—came over to our rambling farmhouse afterward, and everyone ate from a smorgasbord and drank mulled cider and spoke in low shocked voices. As for myself, I hid upstairs. I felt guilty, bereft. Also angry. If he hadn’t so simply ignored me, things might have turned out different. I barricaded my door that night and spent hours memorizing my brother’s narrow freckled face, his edgy voice, his gawky mannerisms, his lame jokes, the Christopherness of him, so I could hold him as long as possible in the decaying cradle of memory.

Instead of sleeping in my bed that night, I lay fitful on the floor, twisting around in my funeral clothes, hugging my doll Millicent, who was my first confidante and imaginary little sister. Why, I thought, should a grieving sibling sleep comfortably when her brother was stuck inside a dark box all alone? I felt hopeless, deeply discouraged. I didn’t want my brother to be dead. I didn’t want to be a witch. I had no interest in knowing ever again what might happen in this world before it did. My foresight was one thing. But to shift the flow of my brother’s will so it might not collide with his fate was as impossible as reaching out to grab one of those falling stars, hold it in my palm, and blow it out. Still would be beyond me, had he survived when a woman fell asleep at the wheel and crossed lanes, flying head-on into the Gilchrists’ car under a new moon. Which is to say no moon at all.

My mother, for all her Christian religion, sank into a numb depression and stayed there for a long time. When I called her Mom she only sometimes answered; more often she just looked blankly right through me. Since she paid more attention to me when I addressed her by her first name, Rosalie, it became a habit that stuck. She took a year off from her job as a science teacher and spent days doing volunteer work for the church. None of her good deeds, from serving meals at a homeless shelter to clerking in the United Methodist thrift shop, buoyed her spirits. Though I didn’t want to believe it, some days I sensed she blamed Christopher’s death on me. This she would have denied, if asked—I didn’t—but it was there in a random gesture, a quiet phrase, a clouded glance. I do know she prayed for me. She told me as much. But I’m glad she prayed in silence.

Looking back, I see that I was trying my best to breathe.

If it hadn’t been for Christopher’s death, I probably would not have been raised by my father like I was. In Rosalie’s grieving absence, my dad and I reinvented our kinship. He was far too wise to bury his own sorrow by attempting to transform me into some factitious son, tomboy though I admittedly and perhaps inevitably was. High-spirited and gregarious, a magnet to a constant stream of friends, my brother had been nothing like his introverted sister, Cassandra, who more often than not kept her own company. Nep did his level best not to Christopherize me. Nor did I feel compelled to try to make my father into an older brother figure.

Instead, we began hanging out together, a fond parent and his punk kid. He drove me to school and picked me up. Together we made three-bean chili and shepherd’s pie for dinners on the nights when Rosalie arrived home late. We listened avidly to his old jazz records, shunning the seventies pop music that filled the airwaves. Weekends I sat on a tall stool next to him in his repair shop, really just a converted barn near the house, filled with widgets, wires, gadgets and tools, boxes of tubes both glass and rubber, a thousand broken household things he, poor man’s Prospero, hoarded for spare parts and used to fix whatever people brought to him that wasn’t working. Radios, tractors, toasters, clocks, locks. He even mended a clarinet for some boy in a local marching band. Nep could, I marveled, take almost anything that had fallen into disrepair and make it new again. Young as I was, I recall thinking, He’s the last of a breed, Cass. Don’t take this for granted.

I was crushed by my brother’s predicted death, stunned by my mother’s disappearance from our lives, and inspired, warmed, and moved by my father, who, however much I’d loved him before, was a revelation to me. The man was possessed, in his quirky way, of genius. I thought so then and still do now, even in the wake of all these intervening years.

What needs to be said here is this. If I hadn’t been fathered so much by him, I might not have become, like him, a diviner. For however skilled he was at transforming the ruined into the running, and however steadfast a husband and father, Nep—shortened from the whimsical if preposterous Gabriel Neptune Brooks—was born with a gift that went far toward making those other masteries possible. There had been many diviners in the paternal branch of the family. All had been men. Over the next decade, I became the first female in a lineage that extended unbroken back to the early nineteenth century, as far as our family tree has been traced. This has been my blessing, my bane, and, aside from my own children, my legacy for better or worse.

It was as a diviner I made the discovery on the Henderson land.

Before Henderson’s, I never had a fear of being alone. Walking in the forest or crossing some unfamiliar field in the predawn morning or darkening night never bothered me. As my father’s daughter, I knew the flora and fauna here as well as I knew the names of my sons. I never worried about getting lost because I never got physically lost. Not in the field, not while divining. Besides, worrying never got anybody found.

Not that I wasn’t used to coming upon things that were unexpected. Calm quiet and then the quick stab of discovery, those are, for me, the two poles of divination. Mine is by definition a loner’s trade, a kind of work that involves spending a lot of time both in your head and on your feet, conversing with the invisible and sometimes the inexplicable. How often had I been dowsing a field in search of well water, or a mineral deposit, or something lost somebody wanted found, and thought, Nobody’s walked here for decades. Possibly centuries. So what is this half-buried clawfoot bathtub doing out here in the middle of nowhere? Where is the plow that went with this lonely wheel?

You get pretty far out into the wild sometimes when you’ve hired on with a person who wants to settle fresh terrain. After the twin towers went down, I found myself exploring bonier, harsher, uninhabited land for people from the city looking to relocate, to Thoreau for themselves a haven upstate. But even before that, with so many people building their way into the wilderness, developing the backlands, I had been asked by locals to suss out the prospects of one tract or another. Analyze what the aquifer was about, the prospects of creating more Waldens in the mountains. And so it wasn’t unusual to find myself way off the beaten track.

It was the third week of May. Rained overnight. The reeking skunk plants were well up and the delicate jack-in-the-pulpits wagged their cowled heads in the scrub shade. Overhead, mammoth clouds fringed in silver and charcoal flew hard and fast toward the Atlantic coast a hundred or so miles due east. Noisy warblers flitted in the high branches. Redstarts and yellowthroats. Thrushes conversed, invisible in the near distances. The surveyors had finished up a week before I came out. Their Day-Glo orange flags dangled brazenly from branches—property lines for projected building sites.

Here was a four-hundred-plus-acre parcel that needed consideration. Maybe a hunter had hammered two boards together on this place once, or some early settler chinked up a winter cabin that had long since fallen down. Now it was a habitat for coyote families, black bears, whitetail deer, even the occasional shy fisher cat. Heavy swaths of sugar maple and tall ash gave way to sheltered fields ringed by wild blueberry and serviceberry. A beautiful land, neither worked nor spoiled by man, going back almost forever. A deciduous Eden.

Though I had never traversed this valley before, it wasn’t entirely unknown to me. Christopher and I used to have a cave hideout in the rugged cliffs high above, along its eastern edge, and indeed my parents’ house was but a few miles’ hike beyond that rocky ridge. My developer client was looking to dig a pond large enough to call a lake, around which he planned to build an enclave of upscale homes. I almost felt—no, I did feel blameworthy doing my own survey of his lands so the tall rig could be brought in to drill. And before that Jimmy Brenner with his dozers and Earl Klat with his chainsaw singing and his skidder to make a pretty mess.

I had cut a dowsing rod and was walking, daydreaming a little. Whenever I sensed a sweet spot, even if the stick wasn’t reacting, I stopped and looked around. A dowser who knows what she’s doing can half the time anticipate where the land will give up its water beneath. A big patch of wild leeks reveals nearly as much as a witching stick does about a proximate trove of water near the surface. I drifted along through a thicket of shadblow and wood rhodies all waist- and shoulder-high. It smelled like strong spring, that sex and excrement odor of the world reawakening. There was a narrow curtain of lime-green and red buds at the end of this scrub corridor where the woods picked up and the land began to rise a touch. A redwing blackbird cried out over my left shoulder not far away. Again, a telltale sign there would be at least a shallow vein of water here, as redwings prefer to nest in cattail wetlands.

I was feeling okay. My twins were in school. They wanted to go to camp this year, where they could play baseball and swim and be free of me, and I was going to let them. For all three of us this was a big deal. Because they were going to the same place, I knew Jonah and Morgan would be fine. Would have family right there to look out for them. Meant an empty house for me, but part of Mama Cass—one of my least favorite nicknames, and I had more than a few, from Andy to Assandra, given most people avoided the mouthful Cassandra when addressing me—looked forward to the prospect.

Not that I had a single iota of a plan for what to do with my fancy free, beyond the couple of add-on summer school courses the district administration had agreed to, at my request.

I needed the extra work to pay for the boys’ summer away, which wasn’t in my budget. Remedial reading for some younger students and a continuing education course in my favorite subject, Greek myth. I could do worse than wander behind Odysseus for a few months with my aging pupils, or discuss with them the twelve tasks of Hercules, the story of Pandora’s box. I even proposed to screen that old camp classic, Jason and the Argonauts, with its stop-motion animated sword-wielding skeletons, ravenous Cyclops, and serpent-haired monster Medusa.

Then, without warning or any clear reason my mood should change, a black sensation just poured in, over, and through me. It felt as if a spontaneous, malevolent thunderhead had come flying fast over the ridge to instantly eclipse my world. I was, essentially and all of a sudden, deeply depressed. In retrospect, I wonder if I didn’t weep. Must have blinked through my tears because I did move forward out of the flat scrub and into the edge of the forest there.

A girl. Maybe in her middle teens. She wore a white sleeveless blouse, bedazzled with large dark violet flowers, fanciful orchids or gardenias, which was knotted just above her navel. A denim skirt came down not quite to her knees. Barefoot. Her feet pointed outward in a kind of loose relevé, like some ballet dancer frozen in the classic first position. Her wavy hair was brushed neatly, elegantly, over her shoulders, as if she were going to a party. She was hanged with a rope about her neck, not swaying in any breeze, but as dead still as a plumb stone. Her face bore an unaccountably serene, unforgiving half-smile. Her pale, quite colorless eyes stared straight ahead. She seemed somehow familiar, but that couldn’t be right.

For one last moment of hope I thought, No, this was a doll. A horrific and perfectly wrought wax figurine. Lifelike to a fault. Its martyrdom here was ceremonial. Some sort of devil worship or maybe a terrible practical joke. Prankster drugged-up teens from a nearby town with nothing better to do than hold a sick ritual, a hazing in the middle of nowhere. Then I looked once more at the ashen face. This was no mannequin, no lifelike dummy. She was none other than a girl who was alive probably last week, maybe yesterday, and wasn’t alive now.

I couldn’t help myself. I wasn’t thinking. I should have left her alone. Shouldn’t have touched anything. It was a crime scene, after all. Instead, I went and embraced her. She was light as a dried cornstalk. A shed skin. Wasn’t cold or warm. I held her in my arms and told her I was sorry, that I wished with all my heart I could have helped her.

Only after a moment of standing there whispering these words did it dawn on me that I myself might be in danger. Averting my eyes from the girl, I backed away from the woods toward the clearing a little. Numb, I studied the shadows shuffling across the ground. The outcroppings of glacial schist that jutted up here and there. The thin pools of standing water left from last night’s rain.

Last night’s rain. Her clothing was neat and dry, which meant her hanging happened sometime this morning. I was seized by the sickening prospect that someone was nearby taking me in, deciding how to deal with this unexpected, unwelcome intrusion. Like him, or them, I needed to think what to do. Slowly, in a quivering whisper, I began to spell the word patience backward. One of Nep’s many quaint and sane methods for clearing the mind before beginning to dowse. But this was not a usual divining, and I didn’t make it through all the letters before realizing that the immediate world had gone quiet. It would have been comforting to hear some birdcall. No air moved through the trees to rustle their budded limbs and first leaves. Gone were the tree frogs’ peepings I had heard. The dark tide of feeling that had engulfed me before now switched into another register. I became alert and focused and oddly unfeeling.

A hasty breeze arose. The highest branches of the trees creaked like rusty harrow tines. I turned in place and looked back the way I had come. A narrow path to the south of the scrub flat, which I hadn’t noticed before, led through the thick growth toward a copse of cherries and ironwood beyond. Deer trail, I guessed, nothing to do with this girl. I turned to face her again. What unspeakable terror she must have experienced. Yet it didn’t look like she had struggled. She appeared shocked and forlorn, yet so eerily serene. Which was more or less how I felt, though not serene but rather momentarily emptied, blank. Seemed as if I should apologize to her once more, this time for having to leave her here alone. Her feet were only a stool’s height from the ground carpeted with last year’s dead leaves and long creeping lovely ribbons of staghorn clubmoss. Curious how the ground around her appeared completely undisturbed. As if she’d been put here by some creature with wings.

Without thinking, I asked aloud, “Is anyone there?” My voice sounded smaller than I had ever heard it before. Hollow, reedy, and helpless.

Faint as a half-forgotten memory, I heard a family of chickadees call to one another. Like distant silver bells chiming an hour, their song insisted it was time to leave. My feet began to carry me away from the clearing. I had the distinct sensation of being watched, if not by living eyes, then by her calm and accusing ones. Despite my desire not to, I kept turning, looking behind. I must have run part of the way. No one followed me, so far as I could see.

My truck was still parked on the grass just off the washboard country road. Crazy that the sight of an obsolete Dodge pickup that needed new brakes and rotors and had way over a hundred thousand rough miles on it and no resale value could give me such a feeling of solace. I clambered in and started the engine. Couldn’t have gotten a connection even if I owned a cell phone, which I didn’t. The original Statlmeyer farm, which ran to thousands of acres when it was first settled, was the very definition of rural. They wouldn’t be building any satellite towers around here for a country mile of years, despite how many developers rolled up their sleeves. My pickup jostled and jerked its way down the hill toward the paved road at the foot of the mountain.

I was hyperventilating, nauseated. Had to get to a land line. The old logging trail was not meant to be driven as fast as I did. A ride that had taken half an hour that morning took me no time at all to get back home. Strange how fear works. The farther from any personal danger I got, the less safe I felt.

“Could I get your name, please?” the woman on the other end asked again.

“Is there any way you can reach him wherever he is?”

“I told you Sheriff Hubert is out. Is this an emergency?”

“Yes, it’s—”

“Hold on a moment.”

Squeezing my eyes shut so tight they hurt, I began e and c and n and e and—

“Sergeant Bledsoe speaking,” a man said. “You have an emergency to report?”

“Yes, yes. I need to report a girl, there’s a dead girl, I—”

Bledsoe asked me questions one on top of the other. Did I know the girl? Could I give him the exact location? When was it that I made the discovery? Would I be willing to take them out there now? Was I all right, did I need medical attention, how soon could they send a patrol car by to pick me up, what was the name of the property owner again? I gulped out answers and he put me on hold for a long minute and came back on the phone to say they had contacted Sheriff Hubert and he’d already left where he was and would meet us at Statlmeyer’s—no, Henderson’s—within the hour. I hung up and went to the bathroom. Washed my face with cold water and looked into the mirror. The visage I saw there was so contorted and distraught it seemed like that of a sister I never had who’d led a very hard life filled with chaos, setbacks, and secrets more terrible than my own. I had never before seen myself in such a harsh light. It was as if I had done the hanging.

Bledsoe drove me back out. He grilled me with questions I answered as best I could from within my daze. At least I had the wit to call my mother and ask her if she wouldn’t mind dropping over so the boys didn’t come home from school to an empty house. I thought it better not to explain what had happened. Other than the fact of that image of the hanged girl, I barely knew what happened myself.

“You’re friends with Niles Hubert, I gather. He said to take good care of you.”

I nodded. Not that Bledsoe saw me. He was driving fast with his lights flashing, no siren.

“How did you meet Henderson?”

“He was referred to me by Karl Statlmeyer.”

“And when was that?”

“Two weeks ago, three.”

“And what did he say?”

“He called me up and told me he’d heard good things about me and wanted to hire me to walk his land, dowse it, and give him some proposals about siting a pond and some possible building lots.”

“And you do what?”

“I’m a diviner.”

“And what does that mean?” His voice was low and flat, as dismissive as a slow flick of the wrist.

I was trying hard not to dislike Dennis Bledsoe with his shaved head and thick black eyebrows, one of which remained raised as if in a state of constant skepticism. Trying hard not to feel crushed by the way he seemed not to believe one word I said, and what he did believe, seemed to scoff at. He was just doing his job, I reminded myself, making necessary inquiries and all. But I had been to a few psychiatrists over the years, attempting to cope with the trauma of my brother’s accident, and more than one of them sounded like him. A little unbelieving, and not a little patronizing.

“Did you notice what time it was when you found the body?”

“I don’t wear a watch, but it must have been ten-thirty, or a little after that. I left home after my boys went to school, got there and spent a minute cutting myself a witching rod, and started walking.” I recalled the angles at which the cloud-softened sun shadowed her face. “Between ten-thirty and -forty.”

“You can tell the time that closely without a watch?”

I didn’t respond.

“So you only met Henderson that once. What’s his first name again?”

“George Henderson. We didn’t meet. He called me up out of the blue, offered me the job, and I took it. I can give you his number. I’m sure he’s not going to be happy about this.”

“No, I guess not.”

Niles was there with another man when we arrived. He opened his arms and held me close for so long that if Bledsoe suspected Niles and I had a history it was confirmed. He released me, stepped back still clasping one hand, said, “Of all people for this to happen to.”

“Nothing really happened. That is, to me.”

Niles finger-combed his hair, an old nervous tic of his. Prematurely streaked white against brown, no doubt because of his stressful work. He gave me one of his cherished frowns—the kind of frown that between friends is really a smile. It was a mute conciliatory scolding, as if to say, Something happened to you all right, who do you think you’re kidding?

This was already midafternoon. The many clouds had flown out to sea, it appeared, and the sky was a cool, pristine blue. We walked down the wet declivity, away from the road. A family of finches peeped and bounded in short acrobatic bursts through the air as we left behind the upper field and entered a fairly dense forest of second-growth maples and hemlock. We had to step over and around fallen branches strewn like uninterpretable I Ching yarrow sticks tossed at random by snowy winters.

I was trying to keep my mind smooth. Back when Bledsoe first picked me up, I had decided I couldn’t afford to see her again. I would escort them as close as possible, get them through that scrub flat to the edge of the stand of trees where she was suspended, and send them ahead by themselves. A lone veery called somewhere above us, sounding for all the world like a diminutive alien transmitting its code name back to the mother ship, eerie, eerie. Spring peepers were carrying on in a lowland off to our left. I could hear Niles breathing more heavily than a man his age ought to.

“How much farther you think it is?” he asked.

“Not much.”

We hiked down through a kind of amphitheater of bluestone boulders shaped like huge loaves, which opened up into the northern end of the long scrub plain. I told Niles we were almost there now and in his kindness he anticipated me. Said, “I’m going to leave you with Shaver once we’re close. No need for you to see this again. Sergeant Bledsoe and I can take it from here.”

As we made our way through the thicket of mountain laurel, it occurred to me that here, of course, was Henderson’s pond. A respectable lake, in fact, if he wanted to go to the trouble of paying for dozers to displace the earth beneath our feet. I glanced around. The flat was hemmed by impressive hills. Wondered if it mightn’t even have been a shallow basin long ago that silted in like many do over time. Such irony. Had I thought of this earlier, I might not have bothered to wander farther. And if I hadn’t, well, then what? I realized I had been somehow drawn away from my purpose here. This morning, without knowing it, I left off divining water and instead had begun to divine the girl.

I saw we were near and told Niles this was the place. She was just up ahead. Not even a hundred feet. Right at the curtain of woods. He told John Shaver, a thin, relaxed, kindly young man whose long white face reminded me of a pony I used to ride when I was a kid, to stay here with me. They’d be back in a little while. Shaver and I didn’t have to wait long. The two men returned in no time. By the look in their eyes I could tell something was awry.

“Nothing there, Casper,” Niles quietly said.

How jarring his pet name sounded then, no matter that it went all the way back to our childhood together.

“That can’t be right.”

“You’d better come and show us where she is. We don’t find anything.”

Hurriedly we made our way in single file through the tall foliage. I was slipping into a panic because I didn’t want to see the hanged girl again. But I knew I couldn’t leave her out here unclaimed for another minute. She needed to be taken down from her gibbet, wrapped in the rolled tarp Bledsoe had carried in for the purpose, and taken home to her mother and father and family. I was soon enough running and had left the others behind when I emerged from the undergrowth to stand breathless and gasping at the edge of the woods just where I’d stood hours earlier.

There was no barefoot girl in a floral print blouse and denim skirt hanged with a rope by the neck. Everything looked exactly as it had that morning except for her not being there staring at me with those quizzical eyes.

I wheeled around and shook my head as Niles came up behind me with a face full of questioning. I turned toward the wooded cove again. Nothing. I walked swiftly to the very spot where I had held her in my arms, light as gossamer, but nothing remained of her. This wasn’t possible. Niles was saying something about how we must not be in the right place, and I desperately wanted to agree with him and even began to say so. But when I glanced down, I saw my divining rod lying there among the leaves just where I had dropped it when I first saw her earlier, gazing ahead, so impossibly familiar.

2

ONE OF THE EARLIEST known female diviners in recorded history was something of a wild woman. Her name was Martine de Berthereau, the Baroness de Beausoleil. She was on my mind that afternoon, flickering in and out of it like the light through the budding trees as we climbed back out of the valley and I was driven home. Deep into the evening I couldn’t shake the thought of her and what it sometimes meant to be a diviner.

Headstrong and wily, Martine was as tireless as a migrating hummingbird, fluent in several languages, a gifted mineralogist, an aristocrat who had no fear of dirt under her fingernails. A formidable character, she also had a weakness for alchemy, astrology, and dramatic flair. There have been other female diviners down the years, even famous ones. Lady Judith Milbanke, the mother of Lord Byron’s wife, was well known for her gifts as a water witch. But to my mind none matched Martine de Berthereau. Her story has always fascinated and terrified me.

She made what some dowsers consider her most significant discovery the very year before Galileo claimed the Earth revolved around the sun, an idea that landed him in front of an outraged Inquisition. Theirs were heady times, the roaring twenties of the seventeenth century. Shakespeare’s generation had only recently passed, and Francis Bacon was a rising star. Fresh, untamed ideas and their creators, like exotics freed from a zoo, were suddenly running free, many of them threatening to storm the papal walls. And the Baroness de Beausoleil was seen by some as one of those very escapees. A unicorn, maybe. Or a female griffin.

She had been traveling through France when her son fell ill. While he slept off his fever behind the louvered windows of their room in the Fleur de Lys, an inn not far from the central square of Château-Thierry, she set out on foot to explore the village and surrounding landscape. Her actions would not have seemed out of the ordinary, except that rather than taking her parasol to protect herself from the sun, she carried something the locals had never seen before. Wherever she went, Martine took a trunk carefully packed with all manner of dowsing rods, known as virgulas, made of hazel and forged metals, an astrolabe, and other curious divination instruments. Followed by a few smiling children and scowling adults, she walked the narrow cobblestone lanes behind her virgula, speaking to no one. As a crowd grew, she retraced her steps and circled back to where she’d begun. There in the courtyard, as onlooking villagers murmured, the diviner announced that right beneath their feet ran an underground stream of mineral water, fortified by green vitriol and pure gold, with fantastic healing properties.

A local doctor, Claude Galien, bore witness to what happened next. Some questioned her; some denounced her. But rather than run to the relative safety of the Fleur de Lys, the baroness demanded that the villagers form a committee of their most respected elders. The mayor, the apothecary, the judge. Let them dig at just the spot she had chosen and discover for themselves whether what she claimed was false or true. The hole was dug and waters rich in minerals were found, as promised. Galien was so impressed he was moved to write a treatise about the incident, which was published in Paris, in 1630 : La découverte des eaux minérales de Château-Thierry et de leurs propriétés. Though he suspected the baroness might have noticed the green discoloration on the courtyard stones and deduced that seepage water leaching up to the surface would necessarily be high in ferrous sulfate—my mother the science teacher might say she used accurate data to reach verifiable conclusions by falsified means—he admired her strength of conviction.

For myself, I always believed Galien’s eyewitness account of this miracle should have been the first step toward Martine de Berthereau’s beatification, toward Rome’s sanctifying her as St. Martine, patron saint of dowsers. How nice it would have been for me to point to her in my defense whenever Rosalie found fault in my divining. Instead, as the baroness and her husband dowsed many more mines on behalf of the royal house, and presented their findings to the court of Louis XIII and in particular to the infamous Cardinal Richelieu, her life began to spiral downward.

She had traveled the world—Scotland to Silesia to Bolivia, not to mention every corner of France—in search of ore deposits, silver, gold, iron, and other treasures hidden inside the Earth’s bowels, and had discovered some hundred and fifty mines. More often than not her work went unpaid and discoveries unprospected. But when the good cardinal read in her reports that the deposits—many of which would later prove to be rich and viable—had been located using a forked wand, she was in for a fall. Accused by him of witchcraft, Martine de Berthereau, the baroness of “beautiful sunlight” as her name would have it, was remanded to the lightless state prison of Vincennes. There, with her daughter to whom she’d taught the art of divining, she would die in abject misery, separated from her son and husband, himself condemned to live out the rest of his days behind the iron bars of the Bastille. Not a pretty ending for what was otherwise such a strangely modern life. A woman of science. A world traveler, an adventuress. A working mom. An independent thinker willing to tread way outside the beaten path. Martine was what I always intended to name my daughter, had I ever given birth to a girl. I liked her nervy spirit, and before I knew much of anything about the dark days of the Inquisition, I hated Cardinal Richelieu for his cruel narrow-mindedness. If that was how religious men behaved, I didn’t want anything to do with them.

Divining was always a bone of contention in our household. My mother and Nep, who was ten years her senior—forty to her thirty the year I was born—agreed to disagree early on in their romance about the scientific merits, or lack thereof, of the gentle art of divining. I always found it ironic that she who espoused verifiable facts was devoutly religious, while he who inhabited a world embraced by both postmodernist spiritualists and God-fearing old-timers wouldn’t be caught dead darkening the doors of a house of worship. He could talk about the role diviners played in the Bible until he was blue in the face, but my mother would not be budged off her firm opinion that dowsing was a pagan practice at best.

—But what about Moses getting water out of a rock on Mt. Horeb? Nep might ask.

—That was a holy miracle, not dowsing, she would counter.

—How would the Israelites have lasted all those years in the desert unless Miriam was a diviner?

—Miriam’s well was a gift of Jehovah and had nothing whatsoever to do with traipsing around in the sand with a magical wand.

—What about Thy rod and thy staff shall comfort me? If that rod isn’t a diviner’s rod, what in the world is it?

—It’s a rod to smite atheists like you. Your father probably knew the old adage Spare the rod and spoil the child. More’s the pity he didn’t know one rod from another.

Naturally, they endorsed opposing ideas about what I should do when I grew up, and I failed neither of them. Few if any make a living at divining. So I followed my mother’s footsteps as a teacher, substituting in social studies and geography, though I could lead an even better class in Greek and Roman classics if needed. And, as well, I took what our friends considered the unusual step of assuming the diviner’s mantle in the grand tradition of the family patriarchs. Usually I felt fortunate to be born into a century when diviners were allowed to practice their art. You might be derided but never damned, laughed at but not locked up. But given where it had taken me today, fortunate was the last thing I felt.

Yet my father, whom I revered even more than the great Martine, had never betrayed any concerns about his own divining, or bringing his children into the guild. Divining was just part of his life and never bore with it the threat that always seemed to shadow me. The first time I tagged along with him on a dowsing job I couldn’t have been more than eight, a redheaded beanpole of a kid. A summer morning, the year after my brother was gone, Nep knocked on my bedroom door.

—You got anything going on today, Cassiopeia? he asked.

—Nothing much.

—Now you do. Get dressed, and put on your shoes for once. Wear clothes for a walk through brambles. We’re going to look for water that’s clever at hiding.

As we drove in the orange sunrise, I knew I was entering a world I’d figured would never be mine even to visit, let alone explore with my father. Not a little terrified, I was given a forked stick fresh-cut by Nep, who took some pains telling me just why he picked the tree he hewed it from—in this instance, a single-seed fruit tree—and precisely how to whittle the Y-shaped rod. He also showed me other tools of the trade.

—This is an L-rod, he said, reaching into a worn leather duffel and handing me a pair of television antennas bent at ninety-degree angles. — Some people call them elbow rods. You hold them out in front of you like so, having me grip them chest-high in my fists, their glinting tips pointed forward parallel to the ground.

—What do they do? I asked, trying to keep them from wobbling in my unsure hands.

—I let them show me which way the water runs when I’m bird-dogging a stream. You can make them out of whatever’s lying around. Coat hangers, any kind of metal. My dad had a set forged out of solid brass, real nice.

—Why don’t we use those, then? I asked, only to be told that wouldn’t be such a good idea since my grandfather had been buried with them.

Next, Nep showed me what was called a bobber, a flexible wand weighted on the end that responded by living up to its name, bobbing up and down, or wagging side to side. —It’s best for asking the stream yes or no questions like, You drinkable? Ready to be tapped? Water is smart, Cass. Doesn’t like the words maybe or why. Why is a word for philosophers and water is wiser than philosophers. Got that?

—Yes, I said, trying my best to stay with him.

—Never insult water or anything else you’re dowsing for by questioning it, Are you sure? Once you get good at it, the right answer’s the first answer every time.

He told me that diviner’s tools are all extensions of yourself and nothing less. He finished by saying everything you divine is a reflection of yourself, and this, the only lecture he ever gave me, came to an end as he put all the paraphernalia except for the fresh rod back in the truck.

Then he set out with me, marching across some pale hay fields and through a thicket, listening for vapors’ voices that rose from the earth to be heard and interpreted by us only. Whenever I saw his dowsing rod quiver, jerk harshly downward, drawn by subterranean forces, I did my best to mimic his every gesture. I watched his unmoving hands. Studied his face as it pulled into pucker-lipped focus. I heard him moan a bit, give what later I came to think of as an almost erotic sigh. I walked in his wake while he circled the site he’d figured was most promising. After handing me his rod, he pulled a pendulum out of his back pocket, a heavy hex nut soldered neatly to a length of jewelry chain. I noted his head move left and right as he gathered confidence that this was it, the mother lode.

—Dig here, he told the neighbor who had hired him to dowse, after several deep percussion drillings by the professionals had turned up nothing but pulverized crusher run and sulfuric air. —Hundred and forty-two foot, he said, emphatic as natural law.

I waited, quiet and full of admiration, not quite knowing what I was witness to here.

—That’s all the deeper we got to dig? the man asked.

—Strong vein, too.

—But we drilled the better part of a thousand foot in other spots.

—Makes you feel short, don’t it.

This was the dairy farmer down the road, from whom we would get free fresh milk and guano-dappled eggs and home-cranked lamb sausage in perpetuity, thanks to Nep the local water witch—I’d later wonder why they weren’t called water warlocks—having discovered the plentiful underground stream in his otherwise dry upper pasture. He’s dead and buried now, is good Mr. Russell. He was the one who gave me that little white pony who was a hobbler but as smart as a quirt.

3

STARRY NIGHT, THE DIPPERS high above. And the moon rising, bleaching the evening air so the grass looked like it had been dusted with bone meal. Moon reminded me of a peach pit. It was chilly out. Cold enough for me to see my breath, like a bit of March in May.

Rosalie had already given the children supper when Niles dropped me off. After a couple of hours of a gentle if numbingly repetitive deposition, he concluded by assuring me he would personally go back to the scene, or site rather, since it did not appear to be the scene of anything, in a legal sense. Said he would drive up after dawn, on his own time, before work. Look around again. My conjecture that the hanged girl had been there when I saw her—held her in my arms, in fact—and was removed during the time I left to return with others, might have carried weight but for the very real and problematic detail that the woods appeared untouched.

Not one overturned leaf was to be seen. Not a disturbed twig. The bark this time of year was tender, as pliant as kindergartner’s clay, after all the wet spring weather. But we couldn’t pick out a single branch that showed the least sign of damage from a rope supporting the weight of a girl’s body. The sharpest-eyed forensic expert would, it seemed, have come away with nothing, not that they had the least intention of sending one out. My work in the archaic, quixotic field of divination—a realm populated, in the eyes of many, by dreamers and schemers, hoaxers and head jobs—didn’t help my credibility in the first place. I sensed, too, that had Niles not been my friend, the matter would have been categorically dismissed.

We’d sat together in a conference room at a long table. Its mahogany lamination was curling at the edges, and I found myself nervously picking at the corner of the table while I answered questions. In my life I had never been in such a stuffy, closed room. The overhead fluorescents buzzed like hovering wasps. The two men went over the events of the morning must have been half a dozen times, and half a dozen times I told them the same story. Then Niles, not Bledsoe, surprised me with an unexpected query.

“Can I ask you something of a delicate question?”

Startled by the shift in the rhythm and timbre of his speech, which was much more tardy and lower than his usual voice, I glanced up and nodded.

“Are you on any medications? Taking drugs for anything?”

“No.”

“Nothing at all?” Bledsoe pressed, that dark eyebrow of his raised. “We’re not talking illegal drugs, just for instance an antidepressant or maybe a sedative at night to sleep?”

“I sleep fine without. The answer is no. I’m not on any kind of drugs, prescribed or otherwise.”

“You have been in the past, though, isn’t that correct?” the sergeant continued.

I repeated, “I’m not on any medications now.”

“Nothing to drink?”

“You can’t drink while you’re divining.”

“Has anything like this ever happened to you before?”

“If it had, you’d have been the first to know,” answering Bledsoe’s question while only addressing Niles.

“Casper, just another couple things I need to ask. Bear with me.”

With these words, Niles offered me a smile of sympathetic complicity. Under any other circumstances that smile, which deepened the crow’s-feet at the edges of his beryl-green eyes, would have been gratifying and made me believe the world was spinning properly on its axis rather than out of control. But at that moment, for that instant, I feared his smile. If it were a chalk drawing on a blackboard I’d wipe it away.

“Ask whatever you like, but the girl was there. I touched her with my own hands.”

My defensiveness couldn’t have been more crystal clear. I was feeling attacked, and now all of us knew it. Bledsoe started to say something more, but Niles raised a hand, palm down, in the sergeant’s direction, and the room remained still.

“When you’re divining—” Niles continued, in a mild but serious voice.

“Yes,” staring at the wafer of artificial hardwood in my hand.

“—do you get into some kind of state of mind, say, that’s not what you would think of as being your normal state of mind?”

“It’d be hard to differentiate. I don’t really think about it since I’m too busy doing it.”

“Is it like a euphoria, or dysphoria I think the word is?”

“I suppose it’s safe to say I’m more sensitive to things around me.”

“You’re in a kind of heightened state of sensitivity?”

“I try to be. Extra-sensitive, extra-perceptive.”

“You feel like you’re communing with some alternate world, something like that?”

“I don’t think of it in those terms. You know I’m not into mystical hocus-pocus.”

“Is it like sleepwalking?”

“My father put it like this once. Dowsing is like drowsing, except you’re asleep and intensely awake at the same time.”

“What’s the process?”

I sighed, placed my hands on my knees. “There is no process, if I understand you right. It’s a science that can only be explained in metaphors. You remember when I visited Greece that time?”

Niles nodded.

“Watching the fishermen repair their nets was one of my favorite pastimes there. I loved the idea that you could take something straight and limp, twine and twist it on itself, and turn it into a completely different object. A big loose basket strong enough to hold whole schools of slippery wild fish. Pure wizardry. That’s what I try to do. Just, my thread is so fine you can’t see it. I’m weaving a net to angle for whatever I’m looking to find. It’s my job.”

Bledsoe allowed himself a quiet laugh. I refused to offer him a frustrated glance.

“Don’t be offended,” said Niles. “I’m trying to do my job, too.”

“I’m not offended by you. But it’s obvious your associate doesn’t believe a word of what I’ve said.”

“You’re getting tired.”

“I am, but that doesn’t change what I saw.”

Bledsoe stood, stating in a tone that showed he felt more sorry for me than perturbed, “All right, I got to get back to work.”

That was half an hour before we finished at the station. Well, I thought, nodding as respectfully as I could manage at Bledsoe when he left, who could blame the man? He hadn’t overly troubled himself with masking his disdain for the whole misadventure, but why should he? Anyone who heard what I was attempting to explain would think I was mad, no doubt. I felt way out of my element, both frightened and foolish.

“Cass, do you remember that time you called me in the middle of the night and said you’d had a dream that I was in a house fire? You were very shaken up. You seemed almost, what, shocked that I was even able to answer the phone, that I wasn’t covered in burns.”

“I was glad I was wrong,” looking down at my lap and back up.

“Now don’t misunderstand me, I’m not impugning you. What I’m trying to say here is you’re a person of deep-felt intuitions who doesn’t always get it right. I think you already know I don’t doubt your prowess as a diviner. Some doubt, others don’t. I’m one who doesn’t.”

“Thanks, Niles.”

“No need to thank me because I choose to believe in proven instincts. I remember all too well about your brother. I remember another time when you told me not to go camping in the Adirondacks and I wound up getting shot, nearly killed, by some idiot hunting deer out of season. There are plenty of instances when you seemed able to see better than anybody what was waiting around the corner in people’s lives. I can’t explain it, but I don’t need to. You know me. I’m a boringly practical, down-to-earth man—”

I started to disagree, but he waved me off.

“—who tries to be as objective as humanly possible. Your mother was the teacher who told us about Occam’s razor, remember? Simplest solution’s usually the right one? A lot of people out here try to bullshit me. Hell, almost everybody I deal with does. You’re not one of them.”

“What are you getting at, Niles?”

“What I’m wondering is this. Do you think it’s impossible you sometimes suffer from hallucinations? Don’t answer yet. Let me finish. Let’s say sometimes you hallucinate things that are there. Underground streams, for one. That quartz deposit at Mossin’s. The time little Jamie Schultz ran away and you helped find him. Doesn’t seem inconceivable to me that you might see things that aren’t there sometimes. Things that should be, even could be, but aren’t in any provable way.”

“Are you saying is and isn’t are the same thing?” I tried to smile.

As a way of protecting me from having to explain to my mother why I arrived home in a police cruiser, he drove his civilian car. Niles was like that, a gracious man. He asked after Morgan and Jonah on our way back to Mendes Road, where I lived. I told him the twins were fine but weren’t happy they hadn’t seen their godfather in a while.

“I’ve been remiss.”

Jonah continued to excel in his studies at school, I told him, especially math. His was the kind of mind that noticed, when we were talking one day about Noah and the ark, that the name Noah was hidden inside the name Jonah, just as Jonah was once hidden inside the belly of the whale.

“Bible stories? Isn’t that a little out of character for you?”

“I’m not some rabid atheist, just we don’t go to church, is all.”

“Well, Jonah’s always been ahead of the curve when it comes to smarts.”

“Just the other morning he heard me use the phrase born and bred, and he asked me, ‘Aren’t you bred before you’re born?’”

Morgan, it looked more and more, would turn out to be the family athlete. “Coach Mosley thinks he has state-champion-level play in him. With just a little more discipline.”

“Has he outgrown that glove I gave him last year?”

“You can almost see through the leather on the palm part of it.”

“I’ll look into getting him another one when I get a chance.”

The tedious subject of James Boyd—had the boys asked about him again as I feared they soon surely would?—he bypassed altogether.