8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Grove Press UK

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

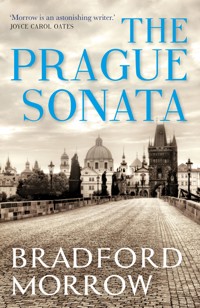

Pages of a weathered original sonata manuscript - the gift of a Czech immigrant living in Queens - come into the hands of Meta Taverner, a young musicologist whose concert piano career was cut short by an injury. The gift comes with the request that Meta find the manuscript's true owner - a Prague friend the old woman has not heard from since the Second World War forced them apart - and to make the three-part sonata whole again. Leaving New York behind for the land of Dvorák and Kafka, Meta sets out on an unforgettable search to locate the remaining movements of the sonata and uncover a story that has influenced the course of many lives, even as it becomes clear that she isn't the only one seeking the music's secrets.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

Praise for The Prague Sonata

‘Twining music history with the political tumults of the 20th century, The Prague Sonata is a sophisticated, engrossing intellectual mystery . . . [Morrow’s] captivating, hopeful book presents a vision of the broken past, restored.’

—Wall Street Journal

‘Bradford Morrow is an astonishing writer.’ —Joyce Carol Oates

‘A treasure of a novel, a deliciously enveloping musical mystery which I read with marvel and gusto.’

—Diane Ackerman

‘This rich, masterful novel brilliantly explores the complex tumble of history, the human capacity for good and for evil, the fragile but redeeming glory of art. Morrow has long been one of America’s finest novelists. And this humanely epic tale is his finest book.’

—Robert Olen Butler

‘Bradford Morrow has written his masterpiece. The Prague Sonata is a rich, joyous, complex journey into the city of Prague, the claims made upon us by music, and several dark, dark corners of human experience.’

—Peter Straub

ALSO BY BRADFORD MORROW

The Forgers

The Uninnocent

The Diviner’s Tale

Ariel’s Crossing

Giovanni’s Gift

Trinity Fields

The Almanac Branch

Come Sunday

First published in the United States of America in 2017 by Grove/Atlantic Inc.

First published in Great Britain in 2018 by Grove Press UK, an imprint of Grove/Atlantic Inc.

Copyright © Bradford Morrow, 2017

The moral right of Bradford Morrow to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of the book.

This book is a work of fiction. The names, characters, places and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, entities or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright-holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

Trade Paperback ISBN 978 1 61185 504 3

E-book ISBN 978 1 61185 937 9

Printed in Great Britain

Grove Press, UK

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.groveatlantic.com

For Cara

I

We are in the situation of travelers in a train that has met with an accident in a tunnel, and this at a place where the light at the beginning can no longer be seen, and the light at the end is so very small a glimmer that the gaze must continually search for it and is always losing it again, and furthermore, both the beginning and the end are not even certainties.

—Franz Kafka, The Blue Octavo Notebooks, 1917

♦ 1 ♦

ALL WARS BEGIN WITH MUSIC. Her father told her that when she was nine years old. The fife and drum. The marching songs, sung to the rhythm of boots tramping their way to battle. The bugle’s call for an infantry to charge. Even the wailing bassoon sirens that precede bombardment and the piccolo whistles of the falling bombs themselves. War is music and music is war, he said, breath strong from his evening stew and mulled wine.

The girl looked up from her pillow and said nothing. This soldier father of hers, in peacetime a piano teacher at the local conservatory, the man under whose strict instruction she practiced until her fingers ached, was all she had left. She had no siblings. Her mother, already suffering from tuberculosis, had just succumbed to the influenza that was beginning to cut like a scythe across Europe. She knew she needed to remember what he said even if she didn’t really understand. She did her best to focus on him, a raving blur in her candlelit bedroom, more a delirious dream than a man, his voice melodic if a little slurred.

Not just the outset but the end of war is music, he continued with a sweep of his arm as if conducting an invisible orchestra. Screams of the fallen will always play counterpoint to the crack of gunshots, just as dirges of the defeated are the closing theme in any symphony opened by the fanfare of victors. Think of it as God’s duet of tears and triumph, from the day war is declared to the day the surrenders are signed.

Why do people fight wars? the girl asked.

Because God lets them, he answered, suddenly quieter.

But why does he let them?

Her father thought for a moment, tucking the wool blanket under her chin, before saying, Because God loves music and so he must abide war.

Don’t go back, she pleaded in a voice so faint she herself hardly heard the words.

He traced his fingers over her forehead, moving her fine brown hair away from her face so he might see his daughter better. When he kissed her cheek, she could smell the vanilla and cinnamon she’d mixed in with his wine. And that was how she would always remember him, there where he stood by her bed, her papa, whispering his good nights, this wiry wisp of a man in his tattered uniform and thin boots, with coal-dark eyes and a rich tenor voice that never failed to convince the girl of whatever puddings came into his head. She fell asleep lullabied in the arms of a beautiful tune he often hummed to her.

The following day, Jaromir Láska’s furlough was up—his commanding officer had granted him a brief week to bury his wife and make arrangements for his daughter—and he was gone before she woke, leaving her in the care of a widow neighbor. Under her pillow he had tucked what she knew was his most prized possession, a music manuscript he kept protected in a hart-skin satchel. She did not take this as a good sign.

Within a month of his drunken evening rhapsody he was dead, one of the unfortunate last to fall in the war that was supposed to end all wars. Barraged, as she pictured him, in some muddy trench as the tanks rolled through and mustard gas settled over the ruined land like clouds of ghosts, leaving her another orphan of the Great War.

She was packed off to live with a Bohemian aunt in the Vyšehrad district of Prague, capital of what was now to become the independent state of Czechoslovakia. On the crowded train out of Olomouc, clutching a valise containing her few clothes, a photograph of her parents on their wedding day, and that antique manuscript her father had acquired in Vienna long before hostilities began, Otylie made a pact with herself. She would never again listen to men who talked war. And she would never sing or play music as long as she lived.

When war came raging into her life once more on a gray morning, the fifteenth of March, 1939, she thought of her doomed father’s last words. She heard no fife and drum. No bugle blared. The timpani of gunfire didn’t shatter the air. But music was there on the first day just as he had promised. Voices rose up together as masses of Czechs crowded Wenceslas Square to protest the German troops marching into Prague.

Otylie, now thirty, saw the unfolding nightmare from behind the sheer curtains of her third-floor apartment window as a wan sun struggled to peek through the clouds. Many thousands of men and women bundled in overcoats and scarves were pushed aside by the advancing soldiers, shoved against the facades of buildings as they defiantly sang the Czech national anthem. A frigid wind blew across the cobblestones under a sky dim as an eclipse. Crisp snow fell over the spires and statuary while the crowds sang with patriotic anger at the occupiers, Kde domov můj . . . Where is my homeland? The opening line of the anthem had never before made such poignant sense, Otylie thought. A requiem for the dead had begun and, look, the first shot hadn’t even been fired.

Her immediate concern was for her husband. Jakub had gone to work early. Would he get back home before the inevitable violence broke out? So many of Prague’s narrow, serpentine streets would be dangerous to negotiate if a throng were to stampede or the troops began making arrests. His shop was near the river by the university, in Josefov. There he sold antiquarian artifacts, religious objects, some musical instruments, a miscellany of collectibles.

If he had any knowledge of what was happening, he would right now be spiriting the most precious items to his back-room safe so he could lock up the shop and return to the flat on Wenceslas Square that his family had inhabited for generations. First he would move the finger-polished ivory mezuzot, ornate menorahs, and old siddurim out of the display window. Next would come the early violins and rare wind instruments. Under an old horse blanket he would hide the harpsichord with its cracked soundboard, dating back to the year Mozart completed Don Giovanni here and conducted it over at the Estates Theater. Some first editions and manuscripts by lesser composers—Franz Christoph Neubauer, for one; or cellist Anton Kraft, who worked closely with Haydn— would be locked in the bottom drawer of his desk along with a clutch of letters from Karel Čapek, who had coined the word robot. Jakub Bartoš’s shop was a mishmash of culture, Jewish and Czech, his twin birthrights. It wouldn’t be so much a matter of salvaging inventory, Otylie knew, as protecting heritage.

Whispers and shouts echoed in the hallway of the apartment building. Someone asked what in the world was happening and another answered, Didn’t you hear the radio this morning? Our army’s under German command now.

I don’t understand.

The Führer ordered President Hácha to an emergency meeting last night, the first woman rasped as Otylie pressed her ear to the door. Dragged him up to Berlin without notice, sick as the old man is. They’re saying Hitler threatened to bomb Prague into rubble if Hácha didn’t hand us over to the Reich’s protection. So he signed in the middle of the night.

Doesn’t sound like he had much of a choice, the other voice responded.

No, and besides, the Germans had already overrun our army in Moravská Ostrava. The radio said Prague would be occupied this morning, but I didn’t believe it until I saw the troops with my own eyes. Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler they’re called.

I call them monsters. Ježíš Maria, what are we supposed to do?

Stay calm, the radio told us, and go about our business as if today were any other day of the week. Imagine!

Otylie heard more shouting. The conversation came to an abrupt halt. Hands quaking, she sat at the kitchen table and tried to gather her wits. They needed to escape. Jakub was too well known in intellectual circles here to hope the invaders would ignore him. She and her husband had read about the bloody pogroms in Austria just the year before and understood what Hitler had in mind despite his public assurances to the contrary. Maybe the train station hadn’t been secured yet. Perhaps they could get to France or England. Or even from there to America, where Czech immigrant communities, they’d heard, thrived both in its cities and out in the countryside.

Her husband would scoff at such a plan. I may not be the most courageous man, he would say, but I’m no runner.

The problem was, as she well understood, that an important difference separated her from Jakub. She had been devastated by war once, lost nearly everything. He hadn’t. Kubíčku, my Jakub, she thought, panic rising like some flaring ember caught in her chest.

Another neighbor, an émigré named Franz Bittner who had recently moved into the next flat, knocked on her door to see if she was all right. No one in Prague is all right, she managed to say. He shook his head and handed her his marmalade cat, asking if she wouldn’t mind taking care of it until he came back. He’d been outside and said the Germans were advancing in continuous columns across the Charles Bridge. Shaven, grim, disciplined boys in uniform and helmets, each with a jaw set as square as a marionette’s, they marched with rifles bayoneted, past the statues of the Madonna and John the Baptist and the rest. Not one of them glanced up at the sculpted figures mounted on the bridge pillars. All stared ahead toward the towers of the Týn Church as if they already owned the city.

Where are you going? she asked him, holding the poor squirming beast in her arms. No time to explain other than that he’d been a Social Democrat before he fled Sudetenland, was known to the Gestapo as an anti-Nazi, and was going to seek asylum at the American legation. She wished him luck and, after locking the door behind him, set out a bowl of milk for the cat, realizing that in the confusion of the moment she’d forgotten to ask its name.

Her eyes darted around the room before settling on the wedding photograph of her father and mother, posing before a Rhinelandish painted backdrop. She took the silver print down from where it hung and sat at the kitchen table, studying their steadfast if nervous faces, longing to embrace them and ask what she should do.

So many different tones of fear, she thought. Chromatic scales of terror, dissonant chords of dread. Her parents’ was simply the newlyweds fear of somehow failing to make life work out perfectly, to draw the dream toward them as if it were tethered on a golden string and all they needed to do was gently, tenderly pull. She too had felt that fear, though she and Jakub shared a golden-dream life, despite not having had any children. Love’s early anxieties now seemed so innocent. For the first time she fully comprehended her father’s panic at returning to the fields of battle; his wine-inspired lecture about music and war was a heroic, misguided attempt to meld what he most loved and hated.

Otylie rose and peered out the tall window that overlooked the square. More Germans down there now than Czechs. Some in long open-air staff cars carrying officers, flanked by heavily armed SS Guard Battalions. Others, motorcycle troops with sidecars two by two in perfect parallel. Marching men hoisted banners emblazoned with the swastika. It was a brazen show of organization and supremacy.

Maybe Emil Hácha understood what was best for his country, Otylie tried to convince herself. Maybe this wasn’t an aggressors’ invasion, but instead was a way of defending Prague against the depravities of other forces. As she watched the surging masses, she couldn’t help but wonder about those young soldiers marching in tight ranks down alien streets, hearing outraged mobs sing words that were not welcoming. Were they, too, frightened behind their fresh, pink-cheeked military reserve? She saw tussling between day laborers and the German columns along the periphery, beneath the unleafed trees. Several heavy pounding sounds in the distance and a roar went up from the crowd. A drumbeat, also far away. And did she hear the strains of an ambulance or was that the cat crying?

Several hours had passed since the first troops made their appearance. Jakub would surely have left the shop in Josefov by now. The antikva was small, just a narrow cavern with high ornate ceilings, its facade a door and display window. Otylie had to believe he’d finished hiding the valuables, shut off the lights, closed, and locked up. This meant he was either delayed by the growing crowds of townspeople and Nazis flooding the squares and streets or that he had been detained.

Without further thought, she pulled out a suitcase from the back of their bedroom closet and began to pack. Some shirts of his, underclothing, a pair of flannel trousers, and a jacket. His favorite cravat, the black silk one he wore to graduation exercises at engineering school, before he left that trade for the shop inherited from his father. For herself, she folded a few dresses, a sweater, toiletries, a pair of lace gloves her mother had passed down to her. Lace gloves, she reflected, wincing, and set them aside. The silly things we cherish.

She also packed the photograph of her parents. Her chest was heaving although no tears filled her eyes. The room reeled as she tried to catch her breath. With effort, she got the overstuffed suitcase closed and buckled its leather straps in place.

Then there was the matter of the manuscript, a piano sonata in three movements, its staves scored with musical notes in sepia ink by an anonymous hand sometime in the late eighteenth or early nineteenth century. It had been her birthright and burden for these two decades since her father’s death. Birthright because it constituted her father’s most treasured bequest to his daughter. Burden because it never failed to remind Otylie of how that last war stranded her in the world, alone with a child’s memories of a man whose mad and maddening words on their last night together had turned her against the thing.

Guard it as if it were your own child, he’d told her when she was still a child herself. One day this will bring you great fortune.

I don’t want it, she had said, remembering how bitterly her parents argued over the manuscript. Even years later, her mother considered what he had done an outrage, spending three months’ wages to acquire it.

Otylie’s father, like her husband, had always been an aficionado of antique things. But whereas Jakub knew what he was doing, her father, who worked so hard as a musician and instructor and who loved his small collection of old hymnals and early printed music scores, was an easy mark for an unsavory dealer with a trunk full of fake illuminated medieval psalters and supposedly original drafts by a famous composer. When Otylie’s mother contracted tuberculosis, he sold off his precious scores, for a fraction of what he’d spent on them, to pay her medical expenses. The only jewel he kept from his hoard was this one, although he never told his dying wife that he’d hidden it in a corner of the attic reachable only by a ladder she’d become too weak to climb.

In melancholy moments over the years Otylie wondered if this manuscript with its haunted history ought to be destroyed. What reason did she have to believe it was any more authentic than the rest of her poor delusional father’s stash? But sentiment, and maybe faith, always got the better of her. Besides, her father had personally inscribed it to her at the top of the first leaf in the language of his favorite composers, Engelsmusik für mein Engelchen, Alles Liebe, Papa—Angel-music for my little angel, Love, Papa—and still it lay protected in its well-worn satchel. Though reluctantly, she too loved passages of the sonata, remembered how much her father used to adore playing it for her or singing its sweet-sad melody to her as a bedtime lullaby. Once in a while, despite her resolutions, she caught herself humming one of its themes when walking along the river or nodding off to sleep at night.

The fact was, she knew the manuscript was probably important. Jakub himself had done some research once she finally told him about its existence. He had shown it to a pianist friend named Tomáš, who expressed great excitement about the possibilities of its origins. This was several years into their marriage. One would have thought it a dirty secret, the way she had kept the sonata hidden from Jakub for so long. Puzzled but also curious about the manuscript’s history, he tried probing Otylie’s girlhood remembrances. Where and how had her father obtained it? What was its provenance? After several outbursts the likes of which he’d never seen from her, Jakub understood that the personal, emotional connection between the document and her father’s death finally wasn’t his business, so he never delved further into the matter.

The artifact itself, however, fascinated, even obsessed him a little. Its fleur-de-lis within a crowned shield and the name H BLUM in the watermark, he told Otylie, suggested that the paper might have been fabricated in Germany or Austria, but it wasn’t a watermark he recognized. The brown ink, the stitching holes down the left side of the leaves that indicated it had once been bound, even the pagination in a dark russet crayon from a later period—the more he learned, the more everything about the object only underscored its authenticity.

Questions preoccupied him. When was the sonata composed? Where? Was this a copyist’s hand or the composer’s own? Why had someone set down staves of hastily penned music in yet another hand on the unused paper at the end of the first movement, notes toward what appeared to be a completely different composition? And who had written these three enlightened movements?

What an unforgettable evening it had been when Tomáš was finally allowed to perform the piece in his atelier in Malá Strana, on an honest if aging Bösendorfer grand piano, before an audience of a dozen acquaintances, including Otylie’s best friend, Irena Svobodová, who had long urged her to make peace with the manuscript and what it represented.

Three sonatas were performed that night on Šporkova, a short elbow of a street that curves from the bottom of Jánská around to a square where the Lobkowicz Palace stands. The private concert began with the last of Joseph Haydn’s piano works, Sonata no. 52 in E-flat Major, followed by Beethoven’s F Minor, his audacious first, a work the younger composer dedicated to Haydn, who had been his teacher in Vienna. Both might well have been performed in their own time at the palace just down the way. After these came Otylie’s nameless sonata.

The mood in the room was uneasy, hopeful, doubtful. Otylie and Jakub’s friends were excited by the chance to hear the mysterious manuscript played. And yet everyone wondered what would drive Tomáš to premiere this untried work in the wake of such obvious glories. It seemed somehow unfair to the unknown composer.

He performed the first two compositions with real panache. Then, after the clapping ceased, he nodded to Jakub, who brought the manuscript to the piano. Tomáš began to play, his friend carefully turning the pages for him. What unfolded in the first movement was energetic and pleasing, if standard and rather Mozartian. The small audience nodded approval when this classic sonata-form movement reached its satisfying final chord. What transpired in the second movement, however, was unexpected. Melodious descending scales concluded in lyrical eddies, pools of euphony, that defied all laws of spiritual gravity when the waterfall of notes cascaded upward again. The music conveyed joyous esprit that mesmerized its unwary listeners. Then, abrupt as water hitting stone, its rich, poignant tapestries of sound ceased. What followed, without foreshadowing, without warning, was a passage of unspeakable darkness. While Tomáš edged forward through this unsettling soundscape of purest dejection, Otylie found herself hearing the differences between his execution and the way her father used to play these very notes. As dark as Tomáš painted these musical phrases, her father’s interpretation, which she related to her mother’s death, was more tragic yet. Fighting back tears, she shifted in her seat through the third movement, a lovely traditional rondo that brought the sonata to its graceful conclusion.

Silence hung in the parlor after the last note resounded and died away, but then the reaction was spontaneous and overwhelming. A collective gasp and a sudden burst of applause filled the room. Hobbled as the sonata had been by the fact that its performer was playing the work without benefit of much rehearsal, not to mention the unsympathetic acoustics, it was clear even to the most unmusical ear in attendance that here was something significant.

You absolutely must allow this to be studied and published, Tomáš exclaimed.

But Otylie would have none of it. She refused to say why. Even Irena, who knew that the middle movement was deeply painful for her friend to hear, was unable to persuade her to listen to reason. As trays of wine and beer were brought around, Otylie Bartošová thanked Tomáš for his memorable performance. Then, unnoticed, she carefully slid the manuscript back into its satchel, and there it had remained ever since.

Now she could do nothing but wait. Though the sky hadn’t grown brighter, she left the lights turned off and the curtains mostly drawn. The passageway outside her door had fallen quiet. Others had taken to the streets to watch the spectacle or else were cowering at home just as she was. She would never leave without Jakub. At this moment she oddly remembered a joke of her father’s about two barristers who walk into a pub eating baguettes. When they order their beers, the waiter warns them they’re not permitted to eat their own food here. The barristers shrug, trade baguettes, and calmly continue to eat. The thing was, Hitler had pulled a sleight of hand on Hácha. He now held both baguettes and had usurped the pub too. Otylie frowned, wondering if she wasn’t losing her sanity.

Not until sometime past noon did her husband manage to send word to her through an emissary. A rail-thin young man named Marek appeared at her door, a first-year university student who swept the floor at the shop, made deliveries, did odd jobs in his spare time. She let him in, stood with her fists clenched together against her mouth, unable to speak, believing she was about to learn that her husband had been arrested or killed.

But he wasn’t dead. He had vanished into the fledgling underground resistance that had begun organizing as the first rumors of a possible invasion circulated, and was making arrangements for Otylie to leave Prague. Shaken, Otylie was at the same time unsurprised by Jakub’s sudden conversion from shopkeeper to partisan. She knew that though her husband was Jewish, he was driven by a love not just of religion or culture or antiquities, but of country. For Jakub to have so quickly coordinated with like-minded Praguers meant, of course, that he must already have been in contact with them about the growing threat and had kept it from her in deference to her loathing of talk about war. So many people passed through his shop. It had been a meeting place, a microcosm of Prague’s intellectual society. Yet just because she was not caught off guard by his decision didn’t mean she had to agree with it. She glared at this kid with his curly dark blond hair and large soft eyes, exhibiting such rage that he took a couple of awkward steps back toward the door.

You tell my husband, she said, her voice hushed but firm, that I’ll do nothing of the kind and that he must come home. Hned, hned ted’! she suddenly shouted, startling both of them. Immediately, now!

I can tell him, Marek said. But I’m not sure he’ll listen.

Do your mother and father live in Prague?

Marek nodded, a bit sheepish for one his age.

Once you’ve told my husband what I said, go to them, make sure they’re all right. Leave the underground to gravediggers.

Somebody’s got to fight these jackals.

Only fools fight the inevitable, she said, but even as these words came out of her mouth she felt the stinging shame of them, the embarrassment of defeat without a struggle.

After Marek left, she passed an excruciating hour stealing back and forth from chair to window like some hapless spy before finally putting on her coat and scarf and going outside into the mayhem to search for her husband. Things were more desperate in the streets than they had appeared to be from her aerie. Men and women freely wept, many of them shouting obscenities at the Germans, who either couldn’t understand them or were indifferent to what they were saying. Dejected Czech soldiers in drab khaki uniforms looked on in disbelief. Some people threw themselves from windows. A couple of boys from the farmers’ market lobbed square cobbles at an armored truck and then ducked away into the swarm of protesters; otherwise the occupation proceeded almost entirely without overt resistance.

Yet the people continued to sing. Singing was their sole salvo against this tyranny. They sang as if music were a kind of fusillade, as if their voices rising together could meet in battle against the clatter of tank treads and jackboots.

She threaded her way across the city toward Josefov, shoving forward while herself being shoved from every side. On reaching Staroměstské náměstí, Otylie paused, looked at the Old Town Hall clock and the cathedral spires, the pastel facades of the buildings lining the square, and, farther along, glimpsed the fairy-tale castle atop the hill in Hradčany that had towered above Prague for many centuries. What washed over her despair like baptismal water was the belief, the certainty, that all this would survive every soldier in the streets. The politics and plunderers of any given day eventually fade into a dust of unreality, she thought, but the best of what people forge with their imagination persists. More than persists, thrives. Otylie clung to this idea, found in it the strength to continue pressing ahead. It was a simple enough epiphany, perhaps overly hopeful, but the extremity of the moment made the idea seem immense.

When she reached the shop and saw that the lights were off, the curtain on the door was drawn, the door locked, she stood staring for a moment at the handwritten sign Jakub had affixed to the display window.

Odmítám, it read. I refuse.

At that moment Otylie understood that Jakub’s impulses were right. And she realized she might never see her husband again.

Not that she didn’t spend the rest of that freezing, frenetic day looking for him. She knocked on the door of every friend they had, forced her way through the surging multitudes past ranks of soldiers and more soldiers, questioning whether the Reich really needed to send so many to secure the peace among an already defeated people. After spending an hour with Irena, who rued the fact that she was alone with her ten-year-old daughter in the midst of all this chaos while her own husband was off in Brno on business, Otylie arrived home just as the first curfews were announced, in both Czech and German, on wall posters and traffic boxes. Loudspeakers blared in the dusk, ordering people to clear the squares and curbs. That night, alone in bed for the first time since she had been married, she cried until her eyes ran dry. It gave her no solace to know that thousands of others were doing the same.

THIRTY FLICKERING CANDLES lit Meta Taverner’s narrow brownstone apartment in the East Village. Its walls trembled with the light of tiny flames. Candles crowded her bookshelves and windowsills. They adorned her baby grand piano. She held one aloft, a bristling little flag of fire at its crown, between her fingertips. It was well past midnight on a Sunday in late July, the first July of the new millennium, and Meta’s birthday. What better way to celebrate than by turning her whole home into a birthday cake?

All the party guests having finally left, her boyfriend now followed her with their two glasses of champagne as she walked from candle to candle—living room, kitchen, corridor—blowing them out, making a wish at every stop. Soon, her railroad flat was scented with sweet smoke and bathed in urban darkness, glowing with the pale amber of ambient street light.

The last candle sputtered in her cupped hands in the bedroom at the end of the hallway. She sat on the bed, still wide awake despite having partied since late afternoon with a dozen or so friends— fellow former Columbia and Juilliard students, a couple of professors, a few of Jonathan’s colleagues—who had brought presents, food, bottles of wine, beer, vodka. Her final wish, like the others, was difficult, maybe even impossible. But what good were wishes if not to stretch beyond the possible? She blew out the remaining candle and set it on the lip of her bedside table before reaching into the spinning darkness to wrap her strong, lean arms around Jonathan’s hips and pull him down, as if in slow motion, on top of her. They lay in a warm, dampening mesh of limbs, mouths locked in a kiss, writhing out of their clothes. When he finally entered her, she couldn’t tell whether she was giggling or sobbing or both.

When she woke midmorning, Jonathan had left. For the past month, he’d been working seven-day weeks along with others at his firm, fighting the biggest judicial case he had yet been involved in. Antitrust suit; marquee business names. A positive outcome meant a probable turning point in his life, a promotion at the least, but he still found time to make her a pot of fresh-ground coffee. There it sat on the counter next to her favorite cup, with its portrait of Erik Satie wearing John Lennon sunglasses.

Jonathan was a thoughtful guy, always patient with her and her cloistered, quirky crew of friends and colleagues who, she knew, tolerated more than embraced him. They were monomaniacs every last one—tunnel visionaries who breathed, ate, and drank nothing but music, music, music. How did he manage to stay sane when talking with her musical pals, to whom the Iberian Peninsula was less a spot to take a pleasant vacation than the hallowed ground where Domenico Scarlatti composed? How did he tolerate, bored though hiding it well, listening to them argue at the top of their lungs about Hermann Keller’s claim that Scarlatti was, finally, behind his times because he failed to return in his later movements to primary themes as Bach had done, yet didn’t rate as a Preclassic innovator because he introduced nothing to pave the way for Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven? Lunatics all of them, her friends, she knew. Lovable, but nuts.

And those were just the musicologists. The pianists were in another league altogether. One of her pianist friends just last night, tipsy on martinis, had explained to Jonathan, “You need to understand that all great pianists are heliocentric. They’re both the sun and what the sun shines on. The world is divided right down their center. Their left hand is one hemisphere, and their right is the other. Nothing exists outside this sunlit world when they are playing, moving the notes of the universe back and forth, through and through them, keeping the supreme center intact while the sperm flies.”

“Sperm?” Jonathan asked with a laugh.

“Of course, sperm! And lots of it, oceans. Bach had twenty children, if you count the ones who didn’t survive birth. He’s not a composer who wrote the B Minor Mass sitting at the keyboard and staring out the window for inspiration. Bach was nothing but a human musical orgasm. The music came and came out of the man. You know the one about why he had so many children?”

“No. Why?”

“Because he didn’t have any stops on his organ.”

While all this was bandied about, a favorite CD spun in the stereo. The speakers strained with each word of one of Frank Zappa’s anti-establishment anthems. When a neighbor came to the door and asked Jonathan, who answered, if they could turn it down, he went over to the stereo to comply.

“Don’t touch that dial,” warned a lanky man standing at his shoulder.

“Why not?” Jonathan asked, ignoring him as he lowered the volume.

“Because the only way to listen to an insurrectionist like Zappa is cranked up all the way. Anything less is a sacrilege.”

Jonathan was a sweetheart, Meta thought, to put up with all this. She’d met him the summer before when he’d moved back from Boston, where he had gone to college and law school, to take a job at a New York firm. He had stayed for a few weeks with his younger sister, Meta’s best friend Gillian, who was more surprised than anyone to see Jonathan and Meta falling for each other. “You know he doesn’t have a musical bone in his body,” Jonathan’s sister warned Meta, “but that might not be a bad thing. Get you out of your head.”

“I’m already out of my head.”

“Very funny,” Gillian said. “My sole proviso is that you keep me away from the flames if everything goes up in smoke.”

Their first time alone together was when they met for lunch in Washington Square Park. Jonathan brought homemade sandwiches. Meta showed up with pastries from her favorite Italian bakery on LaGuardia Place. Late spring, the blue sky daubed with shape-shifting clouds headed out toward the harbor and ocean beyond. The day was as perfect as an opera set staged by Zeffirelli. They sat on a bench under a plane tree and traded notes about his sister, since what else did they have to talk about, until Meta commented on the distant song playing on a kid’s boom box, saying how much she liked “Crosstown Traffic.”

“You’ve got to be the only person in New York who does.”

“No,” she laughed. “Listen, hear that? Hendrix.”

Jonathan, a little embarrassed, laughed at himself.

“You know,” she continued, head tilted to the side, “I don’t think I ever understood the war in Vietnam until I really paid attention to Jimi Hendrix. It was all words in textbooks and horrible images on the movie screen, but when I heard the Woodstock recording of him playing ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’ it just clicked. Know what I mean?”

He did, he said, although he only kind of did. Still, it wasn’t hard to imagine electric guitar feedback replicating jets. The drums and cymbals, bombs. The throbbing bass, maybe copters spiraling down into an orange inferno.

“Even that song over there?” Meta nodded across the fountain toward where the distorted music was coming from. “There’s machine-gun fire in that syncopated riff right before the chorus. Hear it? Duh-dah. Duh-dah, duh-dah, dud-dah-dahdah.”

“Now I do,” he said, hearing it in fact.

The two sat for a moment, listening. Children screeched as they ran beneath the fountain geyser. Somewhere a dog barked without letup while skateboarders clattered on. Pigeons cooed, pecking at bread crumbs thrown by an old, bent woman wrapped in shawls.

“You still have room for dessert, I hope.” Meta pulled out the goodies she had brought with her. “They had cannoli, profiteroles, and napoleons. I wasn’t sure which you’d like, so I got all three.”

He watched her with a sudden giddy desire, as the daylight caught in her long brown eyelashes and paved smooth panels across the translucent skin of her cheeks and chin. Her wide, porcelain brow had a two-inch-long crescent scar on it, which in his eyes only made her more desirable. Her silk-straight brown hair that fell to her shoulders was parted in an unkempt zigzag down the middle. She repeatedly hooked stray strands of it behind her ear with a flick of the skittish fingers of her right hand. When she did this, her hand took on a curious clawlike shape, somewhat deformed and yet at the same time loose and elegant. At first he thought it might be a tic, but as he began to pay closer attention, he noticed there was something decidedly, physiologically wrong with her hand. Muscle spasm from playing too much? Injury, maybe? He wanted to ask but figured that the story, if there was one, would come out of its own accord. Pointing at an imperfection was hardly the best move to make during what amounted to a first date. Besides, her hair tucking was a mannerism Jonathan found endearing, maybe because it relieved him to think that she too was nervous.

Meta wasn’t classically beautiful, but she was striking, someone who often drew a second glance from strangers. She looked, it occurred to Jonathan, like a person one had known for a lifetime. The simplicity of what she wore—a black-and-white-striped tank top, faded blue jeans just starting to go at the knees, a pair of pumpkin canvas espadrilles—only added to his feeling of warm familiarity. Later that night, he confessed to Gillian that the alfresco lunch had shaken him to the quick. He was convinced he had, that afternoon in the park, fallen in love with his little sister’s friend Meta Taverner.

By Christmas they were inseparable. They traded books, recordings, photographs from when they were younger. They went out dancing. They hit as many heavy-metal rock concerts as classical, from Slayer to Stravinsky, Testament to Telemann—Jonathan gamely teased her, “Meta the Metalhead”—not to mention jazz in sacred cellars on Seventh Avenue. Now and then they discussed moving in together, but for one reason or another this hadn’t come to pass. What was the rush anyway, Meta pointed out, reasoning that the studio Jonathan had found on Tompkins Square was right nearby. They were comfortable enough with things as they were.

The one barrier to absolute openness between them, at least by Jonathan’s lights, was Meta’s reticence about her hand. Seeing that she was never going to broach the subject, he finally gathered up the courage to ask her what was wrong.

“Long story,” she said, her words all of a sudden staccato.

“I have plenty of time.”

Despite herself, unconscious of putting the hand on display, she whisked a bundle of hair behind her reddening ear and said, “Car accident. My father driving too fast. I was in the passenger seat. That’s all, that’s it.”

“Sounds like there’s a lot more.”

“Much as I adore you, Jonathan, it’s baggage I’d rather not unpack,” her voice unwontedly pinched.

“If you ever want to talk—”

“One day maybe. Just not today,” she said with a tight-lipped smile. “I hope you understand.”

He didn’t, but told her he did.

*

The day after Meta’s party, Gillian called to wish her a happy birthday, apologizing again for missing the bash. “I always feel guilty when I get sick,” she said, coughing. “A hospice nurse really can’t afford to be felled by mere bronchitis.”

“We’re all allowed to get colds once in a while, nurses included,” said Meta.

“Maybe so, but that’s not why I’m calling. I still want to give you your birthday present.”

“It can wait. Let me bring over some matzo ball soup.”

“Thanks, but actually, no, it can’t wait. You have a pen and paper?”

Struck by the sharp, serious tone of her friend’s words, Meta reached for a pad. “All right, shoot.”

“You remember that elderly Eastern European woman, the cancer patient at your recital at the outpatient facility?”

“Hard to forget her. She was a real ball of light, despite her illness. I hope she’s still hanging in there.”

“She is, tells me she can’t believe she’s lived to see the year 2000. I’m not supposed to get involved in these people’s personal lives, but it’s not always possible to avoid. So I went last weekend to visit her in Queens. She’s all alone, refuses to consider inpatient care. I took her a goodie basket, some halvah, nectarines, fresh sesame bagels.”

“You went uninvited?”

“I got her address off the insurance records in the database, did everything contrary to hospital regulations. Something told me I needed to go see her and so I did.”

“You’re too much,” Meta said admiringly, her pencil still hovering over the scratch pad, ready to write down whatever would make it clear how any of this constituted a birthday present.

“Here’s the deal. She’s been asking after you, so I want you to take down her address.”

As Meta wrote, she asked, “You want me to go keep her company?”

“No, listen. She showed me something I think you’d better have a look at. After your recital, she mentioned it every time I saw her, but I didn’t really take it seriously until I was there at her home. She pulled it out of a hiding place under the base of this old trunk, what do you call those—”

“False bottom?”

“Right, and showed me one of the most beautiful things I’ve ever laid eyes on. Like something you’d only see in a museum. A music manuscript. She claims it’s from the eighteenth century. Unknown, unpublished, has a whole saga behind it. When she asked about what you did, I told her how, since the accident, you’ve spent your life studying this kind of stuff.”

“You told her about my hand?”

“It only seemed right since she hardly talked about anything besides you. She liked the way you played, liked that you volunteer to perform for people who are too sick to go to any Carnegie Hall. The upshot is, she seems almost frantic for you to see this thing. Can you go?”

“Of course I will. Just so you know, though, the chances are good her manuscript’s a little more recent than all that. But I’m happy to have a look. When are you free?”

“Meta, you need to see her now. Don’t wait for me. I can’t risk infecting her, and she could well be in her last weeks.”

“I’ll go right away. Do I call first?”

“She’s expecting you. Just when you ring her bell, you have to be patient. It takes her a while to get to the door. Happy birthday.”

“Well, Gillie, as birthday gifts go, this has got to be one of the weirdest.”

“You know me.”

“I’m lucky to. Thanks for this. Feel better,” and they hung up.

One of the partygoers had given Meta a large box of Polish chocolate in a bright red-and-gold wrapper—Maestria, it was called, with a card saying Maestria for la maestra. She packed it into her shoulder bag, threw on her jacket, and headed out.

Seated on the subway, she realized her thoughts were as scattered as the newspaper pages on the seat and floor beside her. She was at once tired from having stayed up so late and unnerved by this foray into a neighborhood she didn’t know to see a dying woman she had met only once in passing. As the lights in the tunnel shot by, a small radiant burst caught the corner of her eye and she glanced down at her lap. There on her finger was the ring Jonathan had given her after they made love. He had left the bed and retrieved a small leather box from the pocket of his sport coat.

“I almost forgot,” he said, handing it to her where she lay propped on an elbow, naked in the tangle of sheets and disarray of pillows, then laughed uneasily. “Don’t worry. Not an engagement band.”

She opened it to find an antique silver ring set with an oval of dark green malachite. “It’s beautiful,” she said, and thanked him with another kiss after slipping it onto her index finger since it didn’t fit any of her others.

“Next week we can get it resized,” he said, before turning off the bedside lamp and falling asleep.

The ring kept her awake for a while before she too drifted off. Despite Jonathan’s disclaimer, she knew—they both knew—that he cherished the idea of marriage and family. He and Gillian had grown up in a big, fairly happy clan, and that was, to him, an ideal as steady and present as the rule of law itself.

She had never worn jewelry on her fingers or hands, not even a wristwatch, since she got serious about playing piano as a child. The chafing, the constriction, the slight weight bothered her just enough that it never seemed worth the fuss. But now that she was officially out of contention for the concert circuit, reduced to playing for the love of it at hospitals or for public school children or at institutes for the blind, what good was an old habit that prevented her from wearing a ring?

It had taken her some long, grueling years to come back as far as she had from near paralysis. She’d urged herself through thousands of hours of grinding, arthritic, torturous scales. Several surgeries and intense physical therapy got her to a place where she could perform with quite wonderful competence. But for one whose sole desire from an early age had been to achieve not competence but incandescence, even transcendence, each of Meta’s triumphs during her long recovery was tempered by the inevitable unspoken question, What would this have sounded like if the accident hadn’t happened? Thanks to one of her mentors, she did experience a single, glorious night performing Maurice Ravel’s Piano Concerto for the Left Hand at a gala benefit concert for the Juilliard School at Lincoln Center’s Alice Tully Hall. The reviews lauding her pianistic dynamism and artistry spent more space on the personal tragedy that had interrupted a potentially major career. As much as being back onstage with an orchestra exhilarated her, she hated the idea of being a curiosity. It was best, she believed, that she limit herself to charitable recitals and teaching young prodigies such as she’d once been. Beyond that she would put all of her knowledge and energy into musicological work.

No, she thought as the subway jostled around a bend, strange as the ring felt on her finger, there wasn’t any rational reason to beg Jonathan’s forgiveness and take it off. She firmly folded her hands in her lap, closed her eyes, returned to the present. Was she really about to find an important unpublished score in Queens, of all places? The prospects were slim to nil, she knew. Still, it couldn’t hurt her karma to comfort a dying stranger. Gillie’s birthday gift was a chance to give, she thought as the train pulled into her station.

Yet there was an infinitesimal chance something might come of it. Hadn’t those chorale works of Bach, the Neumeister Collection, only surfaced in the pop-rock eighties? And in the disco seventies wasn’t Bach’s masterpiece, his personal revised copy of the Goldberg Variations, discovered in Strasbourg like some living, breathing unicorn that had stepped out of a mythical forest? Just the decade before, when the British Invasion was at its peak, weren’t two lost Chopin waltzes, tied together with blue ribbon, unearthed in the composer’s great-grandmother’s trunk in a château outside Paris?

Sure, life was brief, art long. But the life of art on paper was notoriously vulnerable, unless it happened to be a drawing by Rembrandt or Renoir. Even the manuscripts of writers and statesmen had a better survival rate than music scores, it seemed. Meta wondered, as she walked down the tree-lined streets of Queens toward Kalmia Avenue, if it wasn’t because people could understand and therefore treasure pictures and words. To many, the notes and staves of a music manuscript might as well be an army of ants carrying sticks and flags down a four-lane highway. Either way, she could have been spending the first day of her new decade on lesser pursuits than chasing a unicorn.

MORE QUICKLY THAN OTYLIE or anyone else imagined it possible, the Nazis reinvented Prague. They reassigned each street and square a German name. The river Vltava, which flowed through the center of the city, became the Moldau for the first time since the Hapsburg rule in the prior century. Czechs, accustomed to driving on the left-hand side of the road, were forced to drive on the right in accordance with German custom. In Prag wird Rechts gefahren! Political parties were abolished, radio and newspapers censored. A torture chamber was established by the Gestapo at Petschek Palace. Jewish businesses were Aryanized even before the deportations began.

Other things changed too, as the new order crystallized. Concealing weapons was strictly unlawful. Possessing a broadcasting set ensured an appearance before a firing squad. Whenever SS troops paraded down streets, passersby were expected to halt, remove their hats, and stand at attention as a sign of respect for the swastika banners or marching band playing “Deutschland über alles” or the “Horst Wessel Song,” anthem of the Nazi Party. The world Otylie had known since she was nine years old was being annihilated.

Every day, as the eerie, seething quiet of vanquishment settled over Prague, Otylie walked to Josefov to see what, if anything, was happening at the shop. Not that she expected to find Jakub there sitting on the stool behind his counter reading, as had been his habit before this nightmare began. She had no idea what to expect. More than once she’d taken the key to the antikva with her, intending at least to remove the provocative sign in the window. But sentries were posted on every corner of the Jewish quarter, and she dared not expose herself as being in any way affiliated with the place. Intuition told her not to pause in front of the store lest her interest be noticed and she be taken in for questioning.

On the fifth day of the Protectorate’s occupation, she side-glanced at the shop facade and saw that the door window had been smashed and boarded up. Jakub’s brave Odmítám sign had been removed and replaced with a poster printed in red and black stating that this establishment was closed until further notice. Otylie knew that it wouldn’t be long before they came knocking on her apartment door.

She hastily returned home, bracing herself for ransacked rooms. After unlocking the door to find everything undisturbed, she grabbed her suitcase and satchel. Tucking the nameless cat inside her coat—his owner, she’d learned, had committed suicide after being turned away by the Americans—she left the building hoping to make it to Irena’s without being accosted. Doing her best not to appear nervous, she gave a submissive nod to a group of German soldiers who stood on a corner, smoking and chatting. One of them beckoned her over, but only wanted to pet the cat before waving her on. After that, she nimbly kept to deserted alleys and back streets when she could, then made a daring dash across a bridge upriver from the Charles, which was blocked by troops. Otylie was welcomed by Irena inside her courtyard flat, where Jánský vršek terminated at Vlašská.

Jakub’s wife left no note for him that might lead the Gestapo to her. She knew he would find her hiding place without her laying down crumbs for the rats to follow.

Within a week of sleepless nights and interminable days her guess was proved correct. But it wasn’t Jakub who knocked tentatively on Irena’s door. Instead it was Marek who turned up again, bearing fresh news, bringing her letters and money. He became their go-between and the one left to plead with her on Jakub’s behalf to emigrate immediately, before the noose was entirely closed, and take Irena with her. No longer in Prague himself but hiding on its outskirts with a small, growing group of resisters preparing ways to mount an armed insurrection, Jakub had a plan in place for her, for them both. He had even made arrangements for her to work with the Czech resistance once she was safely resettled abroad. Her sedate, educated, humble Jakub, who loved nothing better than to hike with her to the top of Petřín Hill to picnic on Sundays or go to the Municipal House in the evening to hear a string quartet, was now a conspirator against the Reich.

Bitterness and uneasy pride were what she felt. The confounding part was that her pride made her unhappy with herself and bitterness left her feeling hollow. The anger she’d always felt toward her father for not having stayed with her now began to form like a wicked storm cloud against Jakub.

What was he thinking? Not of her. Not of them. She sensed her heart was turning on itself, growing black and ugly. Irena reminded her that Jakub had exiled himself from Prague, his birthplace, sending an emissary rather than coming to her himself, because he was trying to protect her from guilt by association. She knew her friend was right.

Irena’s husband returned from Brno, and although he was a generous man, Otylie could see that harboring the wife of a fugitive—for by then the Gestapo were openly looking for Jakub— made him sick with worry. Marek brought her rumors that summer of England’s and France’s impending clash with Germany. The news was sent by Jakub, whose colleagues monitored the situation on their contraband radios in secret safe houses dotting the forests and farmlands surrounding Prague.

Jakub says it is now or never, Marek told her. He says you must listen to him if you love him.

If I love him? she exclaimed. He knows I love him.

Then you must do as he insists. This is what he says.

Otylie Bartošová fled occupied Prague in mid-August that year, not two weeks before Hitler invaded Poland, and Britain and France finally declared war on Germany. Marek was to escort her to a safe house in the woods east of the city, where, if things worked out, her hosts would bring her to say goodbye to Jakub. Travel light, bring little or nothing with you, her husband instructed her. And be prepared to abandon the plan to see each other if the situation becomes too risky. More lives than just theirs were now at stake.

She was giddy with excitement at the chance to see him again. Her own life was largely spent indoors, off the streets, out of sight. She traded her valise for a small traveling bag of Irena’s that was just large enough to carry a spare dress, some clean clothes for Jakub, her parents’ wedding photograph, which she’d removed from its frame, and her winter coat.

What to do with the manuscript had preoccupied her for months. The Germans had already decreed in June that Jews were forbidden to participate in the economic life of the Protectorate. All assets were to be registered and valuables confiscated. She could only imagine how empty the antikva must now be. Though she herself was a lapsed Catholic married to a secular Jew, the Nazis would not see their way clear to such nice distinctions were they to find her. Her heirloom, her troubling sonata, if recognized for what it might be, could be a great prize for the Treuhänder, the Reich’s ministry of exemplary thieves. Her father, Jaromir, had boasted that it was the lost manuscript of a great master. Tomáš and Jakub believed her father’s theory might not be so far-fetched. But Otylie doubted all of it, as a nonbeliever might doubt the existence of angels. Either way, to her it was of little consequence who wrote the sonata. What did matter was that the SS not confiscate her father’s dream, or if they did, that they not have the work in its entirety.

No, she would save it by ruining it. She would split it up into three parts, giving Jakub the final movement, on which she wrote a brief, loving inscription, either directly if she managed to reach him or through Marek if not. The second movement, which made her so sad she preferred never to hear it again, she would entrust to Irena with instructions that if Eichmann’s SS larcenists got anywhere near the pages she should burn them. All the better, she thought, that this second movement ended several staves above the bottom of the page’s verso, where the opening of Jakub’s movement began. More frustrating for the warmongers should it fall into their hands. The first movement with its paternal inscription she would take abroad with her, if she was able to get that far.

If and if and if, she thought. Still, she believed the heirloom would have no more value broken into pieces than some shattered Grecian urn whose mythic narrative could only be rightly read by turning it all the way around in one’s hands. If war destroyed her or her husband or her dearest friend, it would also destroy the music the manuscript mapped.