6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

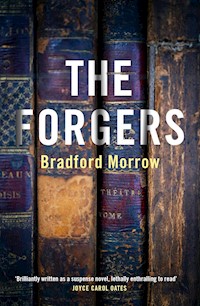

- Herausgeber: Grove Press UK

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

The rare book world is stunned when a reclusive collector, Adam Diehl, is found on the floor of his Montauk home: hands severed, surrounded by valuable inscribed books and original manuscripts that have been vandalised beyond repair. Adam's sister, Meghan, and her lover, Will - a convicted if unrepentant literary forger - struggle to come to terms with the seemingly incomprehensible murder. But when Will begins receiving threatening handwritten letters, seemingly penned by long-dead authors, but really from someone who knows secrets about Adam's death and Will's past, he understands his own life is also on the line - and attempts to forge a new beginning for himself and Meg. In The Forgers, Bradford Morrow reveals the passion that drives collectors to the razor-sharp edge of morality, brilliantly confronting the hubris and mortal danger of rewriting history with a fraudulent pen.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

Praise for The Forgers

“The Forgers is quintessential Bradford Morrow. Brilliantly written as a suspense novel, lethally enthralling to read, and filled with arcane, fascinating information—in this case, the rarefied world of high-level literary forgery.”

—Joyce Carol Oates

“Bradford Morrow is, quite skillfully, paying homage to one of Agatha Christie’s most famous whodunits. Yet even then, he offers a few twists of his own and will keep all but the most astute mystery aficionado guessing about the truth until the end.”

—Washington Post

“Bradford Morrow’s The Forgers is a bibliophile’s dream, an existential thriller set in the world of rare book collecting that is also a powerfully moving exposé of the forger’s dangerous skill: What happens when you lie so well that you lose touch with what is real? In beautifully controlled prose, Morrow traces the shaky line between paranoia and gut intuition, memory and self-delusive fiction, hollow and real love. It’s perfect all-night flashlight reading—Bradford Morrow at his lyrical, surprising, suspenseful, genre-bending best.”

—Karen Russell, author of Vampires in the Lemon Grove and Swamplandia!

“Bradford Morrow illuminates the seamy side of the rare-book trade in The Forgers.”

—Vanity Fair

“In The Forgers, Bradford Morrow hits the sweet spot at the juncture of genre crime fiction and the mainstream novel with an almost mystical perfection. Readers of either form will be gratified and impressed, and those who are readers of both will be thrilled. In its deep knowledge of books and those who trade in them, and in its thousand vivid, unexpected turns of phrase—its depth of both subject and language—The Forgers could have been written only by Morrow and at only the rare and striking level of mastery he has now achieved.”

—Peter Straub, author of A Dark Matter and Ghost Story

“With The Forgers, Bradford Morrow has masterfully combined an exquisitely thickening plot, an informed appreciation of the antiquarian book world, and a deep understanding of what makes the obsessive people who inhabit this quirky community do the sort of impassioned things they sometimes do, up to and including the commission of horrific crimes. Morrow has hit the ball out of the park—The Forgers is a grand slam, in the bottom of the ninth, to boot. This is a bibliomystery you will want to inhale in one sitting.”

—Nicholas Basbanes, author of A Gentle Madness and On Paper

“[An] artfully limned suspense novel . . . The insights Morrow offers into the lure of collecting, the rush of forgery as a potentially creative act, and underlying questions of authenticity render the whodunit one of the lesser mysteries of this sly puzzler.”

—Publishers Weekly (starred review)

“The Forgers . . . stuns from its first line . . . Morrow offers a suspenseful plot that coexists with gritty characters and ominous imagery.”

—Fine Books Magazine

“The Forgers is a reader’s dream: intelligently written, with beautiful details paid to the use of inks and stationary, pen pressures and hand flourishes. Bradford Morrow has created in Will a character rich in criminal indignation.”

—Bookreporter

“Morrow writes with a sure, clear voice, and his prose is lush and detailed . . . Recommended for readers who enjoy atmospheric literary thrillers such as Caleb Carr’s The Alienist.”

—Library Journal

“Will, the narrator of Morrow’s seventh novel, is a fine creation . . . A pleasurable study of the lives of book dealers.”

—Kirkus Reviews

“So well written, The Forgers will take some time to finish as readers might want to reread every sentence.”

—Jean-Paul Adriaansen, Water Street Books, Indie Next selection

ALSO BY BRADFORD MORROW

The Forger’s Daughter

The Prague Sonata

The Uninnocent

The Diviner’s Tale

Ariel’s Crossing

Giovanni’s Gift

Trinity Fields

The Almanac Branch

Come Sunday

First published in the United States of America in 2014 by Grove Atlantic

This paperback edition first published in Great Britain in 2020 by Grove Press UK, an imprint of Grove Atlantic

Copyright © Bradford Morrow, 2014

The moral right of Bradford Morrow to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of the book.

The events, characters and incidents depicted in this novel are fictitious. Any similarity to actual persons, living or dead, or to actual incidents, is purely coincidental.

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN 978 1 61185 460 2

E-book ISBN 978 1 61185 897 6

Printed in Great Britain

Grove Press UK

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.groveatlantic.com

For Cara Schlesinger & Otto Penzler

Historical truth, for him, is not what took place; it is what we think took place.

—Jorge Luis Borges, “Pierre Menard, Author of Don Quixote”

What object is served by this circle of misery and violence and fear? It must tend to some end, or else our universe is ruled by chance, which is unthinkable. But what end? There is the great standing perennial problem to which human reason is as far from an answer as ever.

—Arthur Conan Doyle, “The Cardboard Box”

THEY NEVER FOUND his hands. For days into weeks they searched the windswept coast south of the Montauk highway, fanning out into the icy scrub that edged the dunes, combing miles of coastline looking for a possible small makeshift grave where the pair might be buried. February flurries and short daylight hours hampered their efforts, erasing any telltale disturbances in the sand and semifrozen dirt. Speculating that the severed hands might possibly wash up on shore if his attacker had thrown them out into the churning surf, they scoured the shallows during low tides. Unless salt water had scrubbed his fingernails clean, there was a chance his nails might harbor forensic evidence—especially if he had fought with his assailant, which the disarray at the crime scene suggested he had. Still, the search turned up nothing. It was as if his hands had simply joined together at the wrists, become a pair of wings, and flown away across the gray Atlantic.

The poor wretch survived ten days in the intensive care unit of a New York hospital where he had been transported at his sister’s request. In and mostly out of consciousness, he was unable to speak to either his sibling or the police because whoever dismembered his hands had first struck him with brutal precision on the back of his head—he had been working at his desk quietly, as was his solitary predawn habit—leaving him unconscious in a bath of coagulating blood on the floor of his beachfront studio.

The intruder, it seemed, had been expert at his grisly task or else lucky in the extreme. No signs of forced entry. Marble rolling pin used to crack the victim’s skull was from his own kitchen. Neither footprints nor fingerprints found. No valuables had been stolen, no money, no jewelry. A vintage Patek Philippe Calatrava, an heirloom from his father, lay unmolested, its second hand tracing serene circles, on the victim’s desk. And because the altercation had occurred sometime before sunrise, neighbors had seen nothing unusual in what dim graygreen light the early winter day afforded. After the savagery, it seemed the intruder, much like the hands, had vaporized. None among the regular ragtag of sunrise joggers, who daily ran up and down the beach no matter what the weather, and sleepy dog walkers bundled against the chill had seen anything suspicious. Nor had anyone nearby been awakened by shouts or screams, the incessant crash and hiss of the ocean’s waves having drowned out any such noise, if noise there had been. Besides, all the windows on either side of the house were closed, their curtains drawn tight.

When the postman arrived early on his route to deliver another of the many parcels that came to this address from here and there around the world, he found the front door ajar, which made no sense given how cold the weather was. Over the years, he and the victim had become if not friends then friendly acquaintances, which made it all the more unbearable that, after calling out softly then loudly, over and over, stepping unsure and trembling into the foyer—this was a day he had hoped would never happen to him or anyone else he knew—he discovered the body at the far end of the cottage. Even after an ambulance and police vehicles pulled into the narrow lane in front of the cottage, shattering the peace of this solitary neighborhood like meteors hitting a monastery, the man with no hands was still clinging, with a firm spirit if little else, to life.

The most puzzling discovery investigators made at the scene was of a number of handwritten letters and manuscripts by political and literary lights from earlier eras, all scattered in chaos around the studio. Rare books also carpeted the floor, their covers splayed like dead birds, inscription pages torn from many of the bindings. Lincoln and Twain, Churchill and Dickens, a trove of Arthur Conan Doyle documents lay together with dozens of others. Most had been vandalized, ripped to shreds or spattered with blood and ink from an array of antique ink pots once neatly arranged in a cabinet but now tossed about. Whether any manuscripts or signed books were missing was difficult to determine since there appeared to be no catalogue of the collector’s holdings, and a check later with his insurance company would reveal that they hadn’t been scheduled or insured. But because so many other valuables had not been taken, including books in cases that lined the walls of the studio, the prevailing assumption was that no literary treasures had been stolen, either. What possible logic would dictate the assailant destroy so much precious holograph material only to steal away with others? No, the felonies here appeared to be wanton destruction of valuable property and a severe assault with probable intent to kill, not mere theft.

When Adam Diehl finally died, anything he might have been able to say about the assault—who was behind it, what motivated such barbarity—perished with him. To this day, it grieves me to acknowledge that his death under the circumstances was a tragic if godsent blessing given what an appalling life, mute and prosthetic, he surely would have faced had he survived. Sign language and even speech, given the brain damage that resulted from his head trauma, would have been forever beyond his grasp. He had been, according to his sister, Meghan, ever a recluse, but his injuries would decidedly have isolated him far beyond whatever pleasures he took from living the phantom life. No, surely it was better to lie peacefully in a pretty, manicured cemetery than suffer through the daily grind of such disablement. Isn’t the butterfly whose wings have been plucked by a heedless child better off crushed beneath his heel than left in the grass gazing up at the sky, flightless?

Meghan, whom I’d been seeing for a few years before this incident took place, called me with the horrid news. She was sobbing so hysterically that her breath came in jerky bursts and her words cascaded in raw fragments over the sketchy cell phone connection. Hearing the cries of children at play in the background—why weren’t they in school?—I realized she had left work for the comparatively more private precincts of Tompkins Square to reach out to me. Not knowing what to say, I said nothing, but just listened to her, my beloved Meg, as she told me everything she knew about what had happened. I remember feeling numb and dislocated, alone at my kitchen table, wishing for all the world I was right there with her, kissing away her tears, holding her tight against me.

Divorced, sweet-spirited, an unpretentious, even earthy woman with flame-red hair who in her late thirties could easily pass for someone ten years younger, Meghan ran a used-book shop in the East Village that specialized in her twin fields of interest, art and cooking. She had learned early on to be independent when she and Adam were orphaned in their preteens—boating accident off Montauk, where the family owned the small beachfront house that Adam later appropriated for his studio hermitage—and were raised in Manhattan by a bookish aunt. In those childhood years they had grown unusually close, relied on each other for support and companionship, behaved themselves in front of their bibulous guardian but created a childhood world of their own, one that for a number of years was only really populated by two. Though Adam was the elder sibling, Meghan had always been more outgoing, so she sheltered him in a way, even mothered him at times. Generous to a fault, she let him have the Montauk residence and, as I began to notice, had often paid his bills when he fell behind. As she filled me in on what last details she knew about his injuries, I pictured her in the square, walking alone beneath the barren trees in the drizzle under heavy purple clouds, and my heart went out to her.

“Where is he now?” I asked, trying to be calm enough for both of us.

“They’ve taken him to an emergency room in Southampton.”

“So he’s alive,” I said. “That’s promising, right?”

“Just barely, he’s critical, they told me he lost a lot of blood—” and she broke down crying again.

I waited a little before asking, “Meg, when did all this happen? Do they know who did it?”

“This, this morning,” she answered. I assumed that her ignoring my second question meant she knew they didn’t, or maybe it wasn’t a priority for her just then.

Since I owned a car—a true city girl, Meghan didn’t know how to drive—I offered to take her out to the hospital right away. We would have to rent one, as mine was in the repair shop, but that presented no problem, I assured her.

“God, I don’t know if I can face seeing him. Is that bad?”

“Of course not. He probably wouldn’t even know if you were there with all the drugs they must have him on,” I reassured her. Then, “You want me to come meet you?”

“Later, yes,” she said, abruptly having stopped weeping. “It’s nice of you to offer, especially since you never really liked my brother.”

“I never said that,” was all I could manage, and though she wasn’t entirely wrong about my feelings, I admit I was dumbstruck it would occur to her to say such a thing under the circumstances. But Meghan was devastated, I reminded myself, overwhelmed by such unexpected, staggering news. It was imperative I say nothing to risk our spiraling into some needless, counterproductive quarrel. My job wasn’t to contradict but to let her know she wasn’t alone, that she could count on me. She had, after all, been a rock for me at a time when I needed support not long after I first began dating her. Now it was my turn.

“Look,” I ventured. “I’m sure he’ll be okay. He’s a healthy guy, so that’s in his favor. People survive worse.”

News of Adam Diehl’s assault stirred a lot of interest in the rare book world, at least for a time, even though he was not a major player or even a figure who was all that well known in the trade. Everyone was deeply disturbed by the events, horrified that one of their own, a fellow book lover, would suffer such a macabre attack. At the same time, the usual questions everyone outside this rarefied literary community asked—who did this? wasn’t Montauk always such a safe place?—were supplemented by a profound interest in the books themselves. Who would wantonly destroy books of such quality? Who knew that this Diehl fellow had amassed such an extensive collection? And what was going to happen to the books that weren’t destroyed? No one asked me anything outright, about either the collector or his library, but my relationship with his sister was generally known, and I could sense the unasked questions behind expressions of condolence and concern from fellow bookmen.

After Adam was transported to New York City, I did accompany Meghan to the hospital once before he passed away. Her anguish at seeing him, wrists and head bandaged, leashed to an impressive array of machinery, ignited in me a mosaic of conflicting responses. As anyone would be, I was agonized by Meghan’s grief and fear and appalled to see him lying there in such a state, helpless in the carnival-bright, less-than-antiseptic ICU. Despite the detail in which she had already described his injuries, I had not expected his condition would be quite this bad—I pictured him gravely maimed, not in mortal danger. Yet at the same time, I was still smarting from her comment about my uneasy relationship with her brother, which left me in the unenviable position of having to pretend I was more upset by his state than, in shameful reality, I was. I don’t care to admit it, but a kind of melancholy emotional paralysis veiled itself behind my expressions of loving concern. No civilized person likes to see a fellow human suffering, and I do believe myself to be, despite any faults I might have, civilized. In short, it was a sorry vigil and I did my level best to measure up.

“Adam,” Meghan whispered, breaking the unhappy silence of the room as she leaned close to his gauze-obscured face. Bruises beneath his eyes made him look as if he hadn’t slept for a year, while his aquiline nose gave him a kind of dignity amid the ruin. I had never before noticed that his was almost identical to his sister’s nose. “Adam, honey. I’m right here pulling for you. Everybody is.”

He did not—could not?—respond.

When Meghan side-glanced me, nodding toward her brother, inviting me to add a few words of encouragement, my numbness morphed into a further deepening sadness for her. It seemed inevitable that she was going to be left without any family in this world, the aunt who raised her having died around the time Meghan and I first started dating, and I would soon enough constitute whatever “family” she had.

Taking my cue, I whispered, “Adam, I want to echo what Meghan said, if you can hear us. You’ve got great care here, the best. You just hang in—”

His eyes, which had been closed, came half-open as his head turned a painful inch toward me on his pillow.

“Adam?” blurted Meghan, hope rising in her voice.

“I’ll go get somebody,” I told her, and hurriedly left the room.

By the time I returned a minute later, following his day nurse into the room, he had slipped back into a semicoma while Meghan stroked his once-again unresponsive face. As we were leaving the hospital, she did register surprise at his reaction to my presence, saying, a little plaintively, “He seemed to recognize your voice more than mine.”

“Like I said before, I don’t think he’s really capable of recognizing anybody what with all the drugs they have him on. He just seemed to be in a lot of pain suddenly.”

“You’re probably right.”

“Look, main thing is I’m glad we were there to help as best we could.”

“Me too,” she said, slipping her arm around my waist. “I’m glad you came with me.”

“No more of this business about me not liking your brother, okay?”

“I’m sorry I said that. Promise I won’t do it again,” and drew me closer.

Relieved, even feeling a little vindicated, I leaned over and kissed her before hailing a cab back downtown.

Adam died a few days later. Although Meghan went to visit her brother every morning and evening, I’m embarrassed to admit I came up with legitimate excuses that kept me away from the hospital after that first visit. I made up for my pitiful absence at his bedside by throwing all of my best energies into helping her arrange for cremation and burial. Close as we had long been, we were never closer than during that time. She spent every night over at my floor-through just off Irving Place, near Gramercy Park. We quietly cooked dinner together, me acting the role of sous-chef as she grilled scallops one evening and roasted duck another. Sleepless, we shared wine and screened old science fiction flicks like Metropolis and The Island of Lost Souls. We made love with a fervor only a close encounter with death can inspire in the living. In the simplest of ways, we embraced life by embracing each other. To be sure, Adam was never too far from our minds throughout this period of survivalist mourning, with Meghan remembering happy moments from their past and me listening to each one, knowing that these memories were her best legacy and, as such, were to be respected.

Each of us had already been separately interviewed by the investigators and, after exhausting and even demeaning hours of interrogation, deemed not to be, in that wretched phrase, “persons of interest.” That they had shown particular interest in me was unnerving, to say the least, but after discovering I was home asleep and had neither motive nor means they let me go and pursued whatever meager leads they had. They brought in others for questioning, as well, a few from the rare book field, all of whom appeared to have passable alibis. Asked if I knew this dealer or that collector, I answered honestly that I did and considered them all to be above reproach, for whatever my opinion was worth.

Meanwhile, the press, initially drawn to the maiming and murder of Adam Diehl, began to lose interest. One hometown tabloid had dubbed the slaying “The Manuscript Murder.” Despite the mildly clever alliterative, the phrase didn’t gain much traction—who in the tabloid public gives a good goddamn about literary manuscripts, not to mention rare books?—and the story itself faded from the near-front pages toward the middle and then out of rotation sooner than I or anyone else in the book trade, peripheral or otherwise, might have expected.

During this time, Meghan and I cocooned ourselves away from others, which allowed her, whose resilience profoundly impressed me, a chance to begin her process of healing. We did find ourselves inevitably returning to the subject of who might possibly have wanted to hurt Adam, slay him in such a way, with Meghan concluding there was a strong chance it was someone we didn’t even know.

“He had his own life out in Montauk,” she said, with frustrated resignation. “Close as we were, there’s all kinds of things I’m sure he kept from his little sister.”

I nodded, thinking, Truer words were never uttered.

DYING IS A DANGEROUS BUSINESS. A liberation from suffering, a release from life’s problems, death is also an indictment. Once we’re dead, secrets that we so carefully nurtured, like so many black flowers in a veiled garden, are often brought out into the light where they can flourish. Cultivated by truth, fertilized by rumor, they blossom into florets and sprays that are toxic to those who would sniff their poisonous perfumes. While I did my best to shelter Meghan from certain unsavory discoveries that were made about her brother’s life—like many a sibling, she understandably didn’t want to believe he was anything other than an innocent victim—some damning details would soon enough vine their strangling way into the light. Details that, as fate would have it, I had already surmised about Adam but could not before his death practically or honorably reveal to her. Details that I myself was duty bound to help transit from that darkness of secrecy into truth’s awkward glare. Salt on the wound, I know, and yet it would prove to be an unavoidable seasoning.

Now that I am on the subject of truth, it is important that I offer a confession. Or, rather, an illumination in order to bring into better focus Adam Diehl’s unfortunate death and by way of explaining how I knew what I knew, or believed I knew, about his hidden life.

You see, like Adam, I myself was once a forger. Undeniably, and even unashamedly, triumphantly a forger. There was a time in my life when nothing gave me more joy than forging letters and manuscripts by my favorite writers. Nor was I some naif off the boat who was taken in and, if you will, pimped out by dealers who used my unique handiwork to make millions for themselves while I was left the breadcrumbs. No, I knew who I was and what I was doing. I learned the ropes and forged, ha, my path. And I adored my job. It is no exaggeration to state that the tremulous thrill that surged through me when I lowered my nib to virgin paper was the most erotic feeling I could possibly imagine, the most intoxicating, the most resplendent. The satisfaction of virtuosity put to the test was like none other, was what I lived for and what Diehl possibly strived for, too, though I suspect the gentle art of forgery never gave him the visceral stab of pleasure that it invariably gave me. When I conceived and penned the inscription of an esteemed master in a copy of his or her rarest book—sometimes to a family member, other times to a fellow novelist or poet—an edgy sublimity settled over the moment. It was like electric stardust, say, or a kind of aurora borealis of the mind. Truly, happiness beyond words.

Part of what lay behind this unique feeling was the high-wire nature of the act itself. As a skilled craftsman, the forger has but one chance to get it just right, or else instead of making a book more desirable, more valuable, he has wrecked the thing. But when it is done expertly—and in my heyday I was nothing if not an expert, I think perhaps the finest expert at work during my transient time in the trade—heaven shone down and a choir of rebel angels sang. The rest was about the tense, satisfying pleasure of knowing something others might only try and fail to guess at. Whenever I sold my handiwork to an experienced bookseller for a considerable sum, I knew I had once again hoodwinked the world even as I had ironically made it a richer, more luminous place. I thought—rightly in the beginning, wrongly later—I could rest assured that my spurious inscribed books, my fake letters and manuscripts could travel the precincts of bibliographic connoisseurship with the perfect invisibility of the authentic, above reproach, for all intents and purposes real. Such refined beguilement was the alpha and omega of my art.

For most of my adult life I was a man who was all about ink and paper and first editions. Vintage papers for early correspondence and holograph manuscripts, hand-mixed inks, irreproachable, for lavish inscriptions. Not words so much as letters, their connectors and flow, were what mattered most to me, at least in the beginning, back when I was starting out. Each letter required the right presence and pressure, the tender weight of ink, old sepia, faded black, on my small canvas. The ascenders, the descenders, the choreographic shape and spirit of a comma, these were what kept me up at night. The precision of a period. Single quotes like black crescent moons in a parchment sky. The adage has it, Do what you love. This was what I loved.