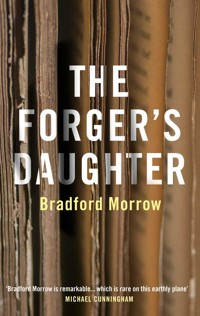

6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Grove Press UK

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

When a scream shatters the summer night outside their country house, reformed literary forger Will and his wife Meghan find their daughter Maisie shaken and bloodied, holding a parcel her attacker demanded she present to her father. Inside is a literary rarity the likes of which few have ever handled, and a letter laying out impossible demands regarding its future. After twenty years of living life on the straight and narrow, Will finds himself drawn back to forgery, ensnared in a plot to counterfeit the rarest book in American literature: Edgar Allan Poe's first publication, Tamerlane. Facing threats to his life and family, coerced by his former nemesis and fellow forger Henry Slader, Will must rely on the artistic skills of his other daughter Nicole to help create a flawless forgery of this 1827 publication regarded as the Holy Grail of American letters. Part mystery, part case study of the shadowy side of the book trade, and part homage to the writer who invented the detective tale, The Forger's Daughter portrays the world of literary forgery as diabolically clever, genuinely dangerous and inescapable, it would seem, to those who have ever embraced it.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

ALSO BY BRADFORD MORROW

The Prague Sonata

The Forgers

The Uninnocent

The Diviner’s Tale

Ariel’s Crossing

Giovanni’s Gift

Trinity Fields

The Almanac Branch

Come Sunday

First published in the United States of America in 2020by Grove Atlantic

First published in Great Britain in 2020 by Grove Press UK,an imprint of Grove Atlantic

Copyright © Bradford Morrow, 2020

The moral right of Bradford Morrow to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of the book.

The events, characters and incidents depicted in this novel are fictitious. Any similarity to actual persons, living or dead, or to actual incidents, is purely coincidental.

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN 978 1 61185 642 2

E-book ISBN 978 1 61185 896 9

Printed in Great Britain

Grove Press UK

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.groveatlantic.com

For Cara Schlesinger & Susan Jaffe Tane

I am not more certain that I breathe, than that the assurance of the wrong or error of any action is often the one unconquerable force which impels us, and alone impels us to its prosecution. Nor will this overwhelming tendency to do wrong for the wrong’s sake, admit of analysis, or resolution into ulterior elements.

—Edgar Allan Poe,“The Imp of the Perverse”

The original is unfaithful to the translation.

—Jorge Luis Borges,“On William Beckford’s Vathek”

A scream shattered the night. At first it sounded feral, inhuman, even unworldly. I leaped up from my wingback reading chair in the study, dropping my book on the wide-plank floor, and heard my husband’s studio door jolt open at the back of the house. When he found me waiting in the front hall, he was gripping his letterpress composing stick, still wearing his stained apron with its rich scent of printer’s ink. We said nothing, just waited in shaken silence. Our sash windows were raised both upstairs and down to let in the evening air, and outside noises, we both knew, often seemed closer in the dark. Still, the scream was so sharp it seemed to have emanated from nearby, maybe even from the unmowed yard out front. I wondered— hoped, really—if coyotes were about to chorus, as the local pack sometimes did upon being prodded by the single wailing cry of an alpha individual. But no other voices joined in. By the time we opened the door of the farmhouse surrounded by enveloping black maples, the world was calm again aside from moths and nameless insects thudding against the porch light, and, from indoors, the faint continuation of a piano concerto by Saint-Saëns on the radio.

“Maisie?” I shouted, peering into the near darkness past the overgrown hedge of lilacs that bordered the yard as I called our daughter’s name.

Moths and Saint-Saëns were joined by the drone of crickets from every quarter of the woods and fields around the house. Nothing else. Often, I reminded myself, the lone coyote who isn’t answered simply moves along. Or perhaps what we’d heard was the death screech of a rabbit being killed by one of those same neighborhood coyotes. In Ireland once, I heard a hare being snatched from life, probably by a hungry fox, and the bloodcurdling scream that ripped the night in half was one I’d never forgotten.

My husband called her name again, louder. “Maisie!”

Our older daughter, Nicole, who still lived in our East Village apartment, wouldn’t join us upstate until the weekend, several days hence. But young Maisie was spending her August here as she had done for half a dozen years running, at the restored farmhouse in the Hudson Valley where we’d made it our annual custom to take off work the last month of summer and flee the city for greener terrain. Earlier that afternoon, she had biked, as she often did, the couple of miles to town—if a church, gas station with deli, antiques barn, and roadside bar can be so designated—to hang around with friends, play video games, stream movies, maybe cook out. Her girlfriends sometimes came here too, even though we couldn’t provide them with a decent Internet connection, and the joys of bird-watching, picking wild blueberries, and swimming in the nearby water hole only went so far. She should be heading home at any moment.

Whereas the scream unsettled us before, now it was the throbbing quiet. At half past eight this time of year there was still light, if faint and swift-fading. Without exchanging a word—Will and I had been married some two decades and often intuited each other’s thoughts— we hastened down the steps, across the uneven bluestone path, and out to the country road, where we headed in the direction of town. Whether consciously or not, he still brandished his metal composing stick, a classic tool used by centuries of letterpress printers and one, I expect, rarely if ever used to fend off a possible assailant.

We hadn’t gone fifty paces before we caught sight of her coming toward us, dully luminescent against the murky backdrop. Not racing on her bicycle, as that shriek—now I knew it had been human—might have led me to expect, she was walking it along with an oddly deliberate, slow, rigid gait, her head tilted forward. When we reached her, I saw the determination set on her tear-streaked face, ashen as pumice in the waning light. My words tumbled over Will’s as we stood together in the unpaved road, hugging the girl, stiff with fear, between us.

“Maisie, what happened? Was that you? Are you hurt?”

“Your brother,” was all she said in response, her voice reedy and breathless, gripping the handles of her old Schwinn Black Bomber, which she had spotted at a yard sale several summers before and lovingly restored with her father.

Looking over at my husband, I saw that he was as bewildered as I.

“You mean Uncle Adam?” I asked, as gently as I could, glancing around in the growing darkness, feeling at once alarmed and a little foolish.

“He was just there,” she insisted, voice tight, and pointed back down the road in the direction she had been coming from.

“But, Maisie. My brother’s been gone since before you were even born. He’s not with us anymore. You know that.”

She shook her head violently, like a much younger girl. “He was, though. I know he’s dead. But he looked just like in the photos.”

“Stay here,” Will said, and walked back into the gloaming—beyond where we could see him—less to confirm whether my dead brother was inexplicably, impossibly, lurking there than to convince Maisie that the road was deserted.

When he returned to us, striding with a bit of fatherly exaggeration, he assured her, “Nobody’s down there, honey. No ghosts, no nothing. Even the birds have gone to bed.”

“Please, I want to go inside,” was all she said in response.

Without another word, my hand on Maisie’s shoulder, I marched next to her toward the house. Will, wheeling the bicycle on her other side, kept glancing back into the dark, apparently pantomiming his concern, as if to reassure her no one was following. Ahead, the familiar windows of the house were illuminated with an amber glow that on any other evening would have filled me with a sense of peace. Tonight, the long ribbons of shadow and light they cast across the lawn had instead an intimidating noir effect.

As my husband leaned the bicycle against the porch rail, Maisie retrieved something from the basket. It wasn’t until we were up the steps and into the entrance hall, with the door closed behind us, that she spoke again, her dark eyes averted. Choking back tears, she managed, “He said to give this to you,” and held out a thin, rectangular package wrapped in butcher’s paper and tied with bakery twine.

Will scowled as he took the package from her hands. “Who said?” he asked, before slipping it into the wide front pocket of his apron.

Now in the warm light of the hallway, it was plain that Maisie had taken a nasty fall. Her right forearm and elbow were abraded and caked with bloodied dirt, and her thin, tanned right leg and both knees were scraped. I interrupted, “My God, what’s this? Maisie, you’re bleeding all over.”

She looked down at herself with reddened eyes, examining her knees as if they were someone else’s. “I guess I must’ve fallen off my bike harder than I thought.” At that, I saw both palms were also chafed.

“You guess? Let’s get you cleaned up,” I said, again hugging her to me, not only to comfort the girl but to steady myself as well. “That looks like it hurts.”

“A little,” was her benumbed response as we walked, Maisie limping a bit, down the foyer into the kitchen, where I washed her wounds with warm, soapy water. To my relief, her lacerations appeared to be superficial, but I fought to hide the anger welling in me, crowding out my earlier fear. I applied antiseptic ointment and bandages, crushing their wrappers in my fist.

Distracted and looking pale himself, my husband set his composing stick on the counter, removed his apron and draped it over the back of a chair, then sat down with us.

“Do you want some cold water, Maze?” I asked, noticing that Will was staring at me instead of at our daughter, his breathing a bit labored. “Or, I think we have some apple juice?”

“Water’s fine,” she said.

Tossing the crumpled bandage wrappers into the wastebasket under the sink, I poured a glass from the tap, dropped in ice cubes, and sat next to Maisie at the round oak pedestal table that centered our kitchen. “You’re safe now, all right?”

She nodded and took a drink.

“I’m confused,” I said, placing one of my hands on her uninjured arm. “It couldn’t have been my brother who gave you this. Your scream, it sounded like—can you say who did this to you?”

“He said you’ll know.”

Will and I looked at each other with even greater alarm, as part of what had happened suddenly became as clear as a shard of broken crystal. Slowly, quietly, I asked her to tell us once more what she saw, in whatever detail she could manage.

Maisie shifted in her seat, wincing, looking embarrassed. “He just, this man came out of nowhere. I was riding, saw the house lights up ahead. Then he was there, like that. I had to turn really hard to miss him, and I skidded and fell. I thought he was going to kill me.”

“Did he have a weapon?”

“No, I don’t know,” she said. “He just surprised me. Like in a nightmare. He had this weird white smiling face. I’m sorry I screamed.”

“Don’t be silly,” I consoled her, hiding my own horror as I smoothed aside a stray strand of hair that had fallen across her forehead and caught on her eyelashes. “Believe me, I would’ve screamed bloody murder too.”

Will was sitting rigid in his chair. Now he asked, “Did this man say anything to you, Maze? Was anybody with him?”

Gingerly wrapping her hands around the ice-chilled glass, Maisie answered, “Not that I could see. He warned me that if I knew what was good for me, I’d get it to you safely.”

“That was all he said?”

“He was kind of in a hurry to get away.”

I noticed the Saint-Saëns concerto had ended and a string quartet had taken its place, probably by Haydn, though many of that era’s string quartets sounded much the same to me. It had the disconcerting effect of briefly becoming a kind of soundtrack, one that made everything in our otherwise very real, very lived-in kitchen, with my collection of copper pans, vintage Amish baskets, and homegrown dried herbs hanging from the rafters, seem like a scene from a movie, a scene I didn’t want us to be actors in.

Will, clearly stricken by Maisie’s description of the man’s threat, reached behind him to remove the package from his apron pocket and place it on the table. “Can’t you tell us more what he looked like? I mean, beyond any resemblance to your uncle Adam?”

“It was too dark, happened too fast,” she explained, brushing tears from her eyes and glancing from the glass of water over at the parcel. For a moment we all studied it in silence. A thin dun mailer, the kind you would send a sheaf of photographs in, or perhaps a children’s book, with a cream-colored envelope secured beneath the knot. Will’s name was written on it with a calligraphic flourish. On either side of his name were skilled pen-and-ink drawings of what appeared to be black flowers. Black tulips. I saw a fleeting look of curiosity pass across Maisie’s face as she regarded the decorations on the envelope, rendered in an elegant art nouveau manner that belied, it seemed to me, the meanness of this act of terrifying a young girl.

Maisie reached over to touch the tulips on the mailer, then snatched her hand back as if to avoid being bitten. Glancing at Will, she continued, “He came at me from behind a tree, or bushes along the road, I’m not sure.”

“How old do you think he was?”

“I don’t know. My headlamp wasn’t working.”

“That we’ll fix in the morning, but about this man. Was he thin? Short-cropped hair, maybe bald?” he pressed. I shot him a glance meant to suggest he needed to ease up, but, intent on Maisie, he appeared not to notice. “Could you see what he was wearing?”

She shrugged her shoulders, jutted her delicately cleft chin. “He came out so fast, and then I was on the ground and he was standing over me with his smile. Then he just shoved that package at me, told me to give it to Will—”

“Wait, so he specifically said your father?”

Maisie nodded; I felt awful for the poor girl. Her cheeks were blushing crimson with confusion and guilt at not being able to answer Will’s salvo of questions.

My husband, who was seated on her left with his arm on the back of her chair, stood up as if to go somewhere, breathed in and out, then sat down again. I waited for him to speak, but he had fallen mute, agitated, preoccupied. For a moment it seemed he wasn’t fully with us in the room, while the wall clock continued indifferently to tick, the refrigerator hummed away, and the faucet softly went on dripping into the sink, as in my haste I hadn’t completely closed the spigot.

“Do we call the police?” I asked him, gently squeezing Maisie’s slender forearm.

Abruptly alert again, he said, “And tell them what? That a man, possibly a ghost, who didn’t at any rate identify himself, gave our daughter—who has no idea what he looks like other than your dead brother—a package on her way home from her friends’ house?”

“Will,” I warned.

Hearing me, and all of a sudden self-aware, he turned to Maisie with a concerned frown, and quietly asked, “Look, I know he frightened you. But did he touch you in any way?” He leaned forward and clasped his hands tightly, prayerlike, on the table.

In that moment, I was forced to admit to myself that my husband, three years shy of sixty, seemed even more unnerved by the incident than eleven-year-old Maisie. This was not a criticism but a fathomable truth.

“No,” she said, shaking her head. “At least, I don’t think so.”

“Would it make you feel better if we reported this to the police?” briefly overcoming his stubborn reluctance— the result of a serious encounter years ago—to have anything to do with the authorities.

“No,” she repeated, surely to Will’s relief, and took another swallow of water. She rubbed her eyes with the back of her wrist and forced a smile meant to let us know that she’d answered every question as best she could. “I’ll be fine. Can I go upstairs now?”

“I’ll go with you.”

“Meg, honestly. I’m all right.”

Sometimes I still wished Maisie felt comfortable calling me Mom instead of by my name—though I wished far more that her biological mother had lived to raise the girl herself. My best friend, Mary Chandler, was the only person for whom that appellation would ever make a natural fit. Maisie wasn’t bothered when we referred to ourselves as her parents. But just as she rarely called Will Dad, I would always be Meghan, her loving, stand-in mom, even though I mothered her as naturally as I did our natural-born Nicole.

“There’s an analgesic in that ointment that should help with the pain,” I said, aware that I needed to let her retreat to her room. Unlike Nicole, Maisie, for all her friends, was a private soul, and I’d learned there were times, like now, when I could minister to her afflictions only so far.

“You’ll let us know if you need anything,” Will added, his supplicating expression revealing to me, if not to Maisie, that he was displeased with how he’d handled her disturbing experience. Her eyes still red, she gave him an oddly wise and forgiving smile—the kind only the young can offer to the old, the innocent to the informed— pushed her chair back, and rose.

“Everything’s good. Don’t worry about me.” And with that, she left us sitting at the table looking at each other.

My thoughts were addled as I tried to make sense of what was going on. Why the man had chosen Maisie to be his messenger, the blameless handmaiden of a convicted criminal, I could only imagine. But if he was who Will and I both tacitly assumed he was, I knew he’d have no qualms about terrorizing anybody associated with my husband. Given the thick woods surrounding the front and sides of our house, as well as our isolation here, it wouldn’t have been much of a challenge to spy on us for a time and mark our young daughter as his target. I got up, poured each of us a glass of Scotch, and set them on the table, thinking it was likely cowardice behind the assailant’s decision to make Maisie deliver the parcel on his behalf. Or at least a disinclination to confront Will face-to-face, unannounced, after such a long time and given the bad blood between them.

When I’d heard Maisie close her bedroom door and knew she was out of earshot, I asked Will, my voice lowered, “Henry Slader?”

“Who else could it possibly be,” he said, sipping his drink.

“Is he even out of prison?”

“So it would seem. I’ve spent as little time thinking about him as humanly possible.”

He was right. Slader’s wretched name had rarely come up since his trial and conviction for his brazen assault on my husband years ago.

“But Adam didn’t look anything like Slader,” I said.

“Who knows what he was up to. The question is why he’s doing any of this now.”

We sat at the kitchen table for a time, as the music faintly continued and the clock calmly ticked. I broke our silence.

“Aren’t you going to open the package? Or at least read what’s in the envelope?”

Will hesitated, swirled the contents of his glass, intent upon its golden hue. “You know, it’s entirely possible he’s out there in the yard looking at us.”

An owl, a great horned that nested nearby, hooted. It reminded us both that while, yes, we were sitting in the relative privacy of the house, the world just outside the windows was very much with us. In the distance, a lower-pitched female owl faintly answered our neighbor’s call.

“Maybe we should pull the shades,” I said, eyeing a kitchen window through which I could see nothing other than inky darkness.

He shook his head. “And give him the pleasure? No, I’m sure nothing he’s written or sent needs immediate attention. Damn his eyes anyway. Attacking Maisie, even if he never laid a finger on her, tells me more than I need to know at the moment. I’ll open it in my own good time, when I’m sure he won’t be able to watch.”

I felt bad for both of these people I loved, even as I was petrified about what was to come. More than anything, I hoped Maisie would not retreat back into her defensive shell as a result of this incident. In the first years after she was orphaned she’d been a bit of a loner, withdrawn and diffident, so any circumstances that helped her to blossom and reenter life were ones we encouraged. We’d all worked so hard to get her this far, to where she truly felt she was a member of our family, appellations aside. As for my husband, I worried that he too might withdraw into paranoia from days long gone, paranoia he’d struggled with considerable success to bury. I knew he would share with me what Henry Slader—if indeed it was Slader who’d accosted Maisie—had delivered in this coercive, cryptic way, once he’d had time to digest the tectonic shift that had just unsettled our placid lives. I rose, put my hand on his shoulder, told him I’d shut the first-floor windows and lock up, then left him alone as the string quartet flowed on, a whisper of empty encouragement from a distant century.

When I went to secure the screen door on the front porch, I saw someone stirring on the far side of the road, just beyond the perimeter of light. No body was visible to my eyes, just the vaguest nimbus of a face afloat out there like an illusionist’s trick in a blackened theater. I was reminded of lonely No-Face in Miyazaki’s Spirited Away, or those enigmatic flat-faced Cycladic sculptures I loved to see whenever we visited the Met. But this wasn’t some anime film figure staring at me or an ancient visage carved from limestone. It was palpably real, gradually withdrawing into the woods, never looking away.

My natural impulse was to call out, demand an explanation. But I didn’t dare. For one, my family had been through enough tonight. What was more, I wasn’t sure I wanted to know the answer. As the gaze that was fixed between me and the mystifying face continued for a troubling minute, maybe longer, I realized Maisie was right. The face’s features, however ambiguous and shadowy in what postdusk light remained, resembled those of my brother, Adam, dead these twenty-two years. Murdered and laid to rest without his killer’s ever having been brought to justice.

Impossible. Ghosts were for children and dime novelists. But this apparition was real, and my mind was not playing ghoulish tricks on me. Was the face, so rigid, slightly smiling as Maisie had said? Did I hear soft laughter, or was it the whispering breeze that ruffled the maple leaves and pine needles? I glanced behind me to see if the sound might have come from the hallway. No one was there. And when I turned back again to look across the yard, the face had vanished. Ignoring any fears I felt, I ventured outside and down the steps, where I hesitated by Maisie’s bicycle, clutching the newel post at the foot of the railing. Blinking hard, hoping to see something further, I realized the visitation, or whatever had just happened, was over. I looked up toward the stars, but none were visible. The overcast sky promised rain by dawn.

After lingering another moment, I returned inside, locked the doors, extinguished the porch light, and went upstairs to bed. It wasn’t until the following afternoon, when curiosity drove me out across the front yard in my slicker and into the wooded thicket on the far side of the lane, that I discovered evidence I’d not been hallucinating. An oversize black-and-white headshot of Adam lay propped against the trunk of an ash tree, its eyes neatly and nightmarishly cut out and an elastic string fixed on either side so it could be worn as a mask. Unthinking, I wrapped my arms around myself as if taken by a sudden, fierce chill. This image was one I’d never seen before. My brother looked relaxed, carefree, happier than in most photos of him as an adult. It seemed to have been taken in the last year of his life, given the pronounced crow’s-feet at the corners of his eyes and the deep wrinkles on his forehead. I was afraid to touch the photo mask—it looked like a freakish religious talisman out here among the tiny wildflowers, club moss, and orchard grasses beneath the shimmering canopy of damp leaves.

Strange, I thought. The glossy photograph hadn’t been damaged by the rain that had fallen off and on, a fitful deluge, most of the day. The way the mask had been placed, protected from the elements against the fissured bole of the old tree, seemed, however morbid, almost like a shrine. Not wanting to handle it, distressed that anybody would have been cruel enough to use it to torment us, I left it where I’d found it. As I hurried back through the woodland toward the house, the world before me began rivering, wavering, growing more and more indistinct. No sooner had I brushed away my tears than they welled up again. I hoped against hope that neither Maisie nor Will, nor anybody else, was watching as I made my hasty, unsteady way home.

Once a forger, always a forger. For twenty long years I had been an exception to that truism, never practicing the dark art I had once loved so well, the mystical crafting of a new reality with ink and a steel-nibbed wand. Until I was arrested for injecting countless beautiful faked literary manuscripts and inscriptions into the bloodstream of the rare book trade, I had quietly earned my living as a master mimic, an impersonator on paper of some of the most revered writers in the canon. So fully had I escaped my past, I’d almost forgotten that I myself was my own best forgery. But now my nemesis had returned, angrier, it seemed, crazier than before. If my wife and daughters were the foundation of my life, and the leafy lushness of our upstate house was meant to be free of strife, free of cares, then his message to me tonight was that I was living in a fool’s fortress. One in which barely perceptible fissures could easily open, zigzag from the roof of the building to its base, causing everything to collapse and swallow me whole. We all have demons. Some imaginary, others flesh and blood. Mine had resided for years as an ugly memory, one so suppressed it seemed unreal. Would that it had stayed in the realm of nightmares.

I lowered the wooden blinds, despite my reluctance to convey fear to the man I imagined might be lingering outside in the pitch-dark field, and slowly opened the envelope string-tied to the package Maisie had delivered. Though my wife and daughter were surprised I hadn’t opened it immediately, I couldn’t possibly have risked revealing its contents in front of them, given that I had no idea what Slader had secreted inside. Alone in the letterpress printing studio I shared with Nicole, set up in an extension at the rear of our house, I unfolded the letter.

Dear Will-o’-the-Wisp, it began, We both knew this day or, better yet, night, would eventually come, did we not? Before reading another word I folded it back up and returned it to its envelope. The handwriting, I immediately recognized, was impeccably that of Edgar Allan Poe. My gut went hollow.

I hadn’t bothered to track this man, the true author of the letter, after he had been arrested, tried, and imprisoned back in the late 1990s for his attack on me while I slept with Meghan in our cottage outside the fairy-tale Irish village of Kenmare, near the Ring of Kerry in the southwestern elbow of the country. After I’d made my barest minimum of statements to the authorities, I did my best to cut—sever, slash, cleave—the assailant Henry Slader from mind and memory. Meg and I had moved to Ireland in order to live quietly, simply, above reproach and outside the turbulent, churning stream of life, of which he was a small if virulent part. Pipe dream, I suppose. But then, most dreams are. Still, I never imagined my past would catch up with me in the hinterlands of Eire in the form of a man attempting to butcher me in bed, hacking at me with my own kitchen cleaver, any more than I imagined it would find me again here, a hundred miles north of New York City on a narrow road in the upstate sticks.

Meghan was seven months along in her pregnancy then, so I had more than my share of reasons to get well, or at least functional, as soon as possible. Our idyllic haven having turned out to be anything but, we were set on returning to New York to have the baby. Before our ship sailed back across the pond, I plodded through weeks of recovery and long hours of rehab each day to learn how to work with a partially severed, if nondominant, right hand. My physical therapist, an amiable young woman named Fiona, who filled our time together with tales of a Galway childhood and her passion for bodhrán and fiddle playing in pubs, was more than skillful at her day job. And I, her patient and pupil, strove to make my work with her proceed apace. A southpaw since youth, I hadn’t realized how much I had relied on my right hand to do simple quotidian tasks. Buttoning my shirt, tying my shoes, buttering my bread—these were paltry acts I did unthinkingly before my injury. Now they all became bedeviling problems that needed to be solved. Motor skills had to be learned anew as I healed, methods of compensation practiced and mastered. Many were the frustrating hours when I had to remind myself that going through life with a fleshy crab’s claw at the end of my right arm was better than having no hand at all.

Thanks to Fiona’s expertise, and that of my doctors both in Ireland and stateside, as well as the support of my devoted wife, I succeeded bit by bit. No doubt, my own vinegary stubbornness played its role as well. And on a wet February morning, as freezing rain blistered the windows of the sublet Meg’s friend and former store manager, Mary, had found for us, Meghan, with the help of a midwife, gave birth to a healthy, bouncing, elfin baby girl. At Meg’s insistence we named the child Nicole, in honor of my mother, who I knew would have been thrilled by her granddaughter, though not by the events that had led up to the baby’s father having to flee a would-be assassin. An amateur assassin, quite literally a hatchet man, whose motivations, I had to admit to myself though not to those who held him behind bars, were not entirely without reason.

After Nicole’s birth, I continued my work with a physical therapist on Union Square through the rest of that winter and deep into spring. Meghan and I were bewitched, if run a bit ragged, by the presence of little Nicole in our lives. Insofar as things could settle back to normal after such upheaval, they did, and the fear of Henry Slader that had haunted me slowly began to dissipate, like thinning mist under a strong morning sun. Stretches of time passed now and then without his coming into my waking mind or even visiting me in dreams. His name had surfaced in the local County Kerry papers for a brief period after his crime was made public, but he and his victim soon enough slipped from view. Which was fine by me. Memory is gossamer. Most of us have, I always believed, the attention span of a kitten rushing from one toy to another. Once the food is set down, the string and the tinfoil ball are swiftly forgotten. Whether my theory is true or not, I hold it as close to my heart as a mackintosh in mizzle.