Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: NYLA

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

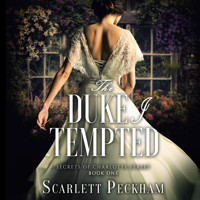

He's controlled. Meticulous. Immaculate. No one would expect the proper Duke of Westmead to be a member of London's most illicit secret club. Least of all: his future wife. Having overcome financial ruin and redeemed his family name to become the most legendary investor in London, the Duke of Westmead needs to secure his holdings by producing an heir. Which means he must find a wife who won't discover his secret craving to spend his nights on his knees – or make demands on his long scarred-over heart. Poppy Cavendish is not that type of woman. An ambitious self-taught botanist designing the garden ballroom in which Westmead plans to woo a bride, Poppy has struggled against convention all her life to secure her hard-won independence. She wants the capital to expand her exotic nursery business – not a husband. But there is something so compelling about Westmead, with his starchy bearing and impossibly kind eyes -- that when an accidental scandal makes marriage to the duke the only means to save her nursery, Poppy worries she wants more than the title he is offering. The arrangement is meant to be just business. A greenhouse for an heir. But Poppy yearns to unravel her husband's secrets – and to tempt the duke to risk his heart. "An astonishingly good debut...The whole book is a breath of fresh air, both a complex, layered story and a soaring romance with two very real people at its heart." -- The New York Times Book Review Author's Note: Dear readers, please be aware this is an angsty, twisty book written in the style of a gothic romance, and there are some dark moments along the path to a happy ending for our characters. No spoilers here, but if you are a sensitive reader please do consult the reviews before diving in. Yours, Scarlett 2018 Romance Writers of America Golden Heart ® Winner for Best Historical Romance "Desert Isle Keeper...The alliance is unexpected, fascinating and a refreshing departure from typical Regency romances, and I never wanted The Duke I Tempted to end." -- All About Romance "Peckham's meticulous character work pays off in spectacular, grandly romantic fashion and The Duke I Tempted ends with particularly cathartic and hard-won happily ever after." -- BookPage "Gothic romances are tempestuous by definition, but this one is dramatic even by those heightened standards...If you want something to speed your heart and stop your breath as you read beneath the covers, with only the meager flashlight beam warding off the enveloping night — then you have a rare treat in store." -- The Seattle Review of Books "A one-sitting, late-into-the-night read, The Duke I Tempted ran away with my heart." -- Book Ink Reviews

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 428

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

Thank you, my darling!

Want more books from Scarlett?

And lo! Now for a whole new series!

About Scarlett Peckham

Copyright

This ebook is licensed to you for your personal enjoyment only.

This ebook may not be sold, shared, or given away.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either products of the writer’s imagination or are used fictitiously and are not to be construed as real. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, organizations, or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

The Duke I Tempted

Copyright © 2018 by Scarlett Peckham

Ebook ISBN: 9781641970327

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

No part of this work may be used, reproduced, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without prior permission in writing from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews.

NYLA Publishing

121 W 27th St., Suite 1201, New York, NY 10001

http://www.nyliterary.com

Dedication

For my mom, my grandmas, and all the other ladies who left their romance novels lying around where I could steal them.

This is all your fault.

(I’m eternally grateful.)

Chapter 1

Threadneedle Street, London

May 31, 1753

“Bloody codding hell,” Archer Stonewell, the Duke of Westmead, murmured to the midnight darkness of his deserted counting-house. Beside him a lone wax candle flickered and went out, as if in sympathy. There was no one here to see him slump, a grown man unmoored by a single slip of paper from a girl no more than twenty.

Your days as a bachelor are numbered, my dear brother, Constance had scrawled in a script so curlicued it gloated. The ball is set for the end of July and it is going to be sensational. No lady who enters Westhaven will wish to leave as anything other than your duchess. Try to enjoy your final month of grim, determined solitude—for I intend to have you married off by autumn. (And do stop glaring, Archer—I can feel it through the page!)

Rain splashed across his expensive leaded windows, a fitting accompaniment to the dread pooling in his stomach. Normally he took pleasure in the empty counting-house, with its rows of ledgers chronicling the growth of his investments into empires and the maps that slashed the country into markets ripe for exploitation. The building was a temple to the gods of order and control, and there was no match for its soothing effect on his soul.

Except tonight, it wasn’t working.

Already, the old fog was descending.

He was not insensible to his absurdity. It was he, after all, who had gritted his teeth and declared the begetting of an heir a matter of urgent moral imperative. It was he who had hired architects to restore the ravaged halls of Westhaven and proclaimed it time to expunge the decaying pile of its ghosts and find a wife to install in it instead.

He’d ordered it. He’d paid for it. Never mind that he preferred his life the way it was: deserted. Pristine. Absent of all reminders of the past.

Never mind that the only thing he wanted less in this world than a wife was a child.

Enough. He picked up his quill and did what was befitting of his responsibility to his tenants, to his family, and to the Crown. He dashed a word of thanks to Constance for her efforts, scrawled his signature, melted a puddle of vermilion wax across the folded paper, and stamped it with the seal of the title that he’d not for one day wanted, and was duty-bound to protect at all costs: the Duke of Westmead.

He put on his coat, extinguished the fire, and walked down the dark staircase to Threadneedle Street, where his coachman was waiting.

“Home, Your Grace?”

He hesitated.

He had been so very, very careful for so very, very long.

“A stop first. Twenty-three Charlotte Street.”

He closed his eyes and sank back into the rhythm of the carriage as it wound its way west toward Mary-le-Bone. It had been weeks since he’d visited the address. Weeks during which rumors of the establishment’s existence had made sneering speculation about the acts that were administered there—and the kinds of men who craved them—a sport in gentlemen’s clubs and coffeehouses.

His interests were precarious. Now was not an ideal time to be branded deviant, or worse.

But some nights, there was a limit to one’s capacity for caution. Some nights, a man needed to be wicked.

And he’d be damned if he wasn’t going to enjoy it.

The town house looked the same. Pale bricks, an unobtrusive terrace. The old black door unmarked, discreet as always. The street blessedly deserted.

At his knock, the maid, a sober girl, took his iron key from the cord he kept around his neck and led him without comment to the proprietress’s parlor. Elena sat by the fire in her customary black weeds. Unlike most women of her profession, her attire was chaste and severe—more like the robes of a papist nun than a courtesan’s plunging silks. Which was appropriate, given that her métier was closer to punishment than pleasure.

“Mistress Brearley,” the maid announced, “a caller.”

He said nothing. Elena knew him well enough to surmise that if he was here, he would not be in the mood to exchange pleasantries.

“Choose your instruments, undress, and wait,” Elena said.

The maid led him to the spare, windowless room. It was lit by candles and held little beyond a hassock and a rack. The girl left him, and he went through the ritual he had perfected over a decade’s attendance in these chambers. From the shelves along the wall, he scanned Elena’s wares. Leather straps, cat-o’-nine-tails, all manner of restraints. As always, he gathered the crisp rods of birch, kept pliant and green in a shallow tub of water, and an elegant braided whip with golden tails. He laid them neatly on a velvet cloth left for that purpose on a sideboard, and folded his clothes beside them. Nude but for his linen shirt, he knelt, facing the wall, to wait for her.

She would keep him waiting. Testing one’s endurance for suffering was, after all, her gift.

He heard her footsteps down the hall before she entered. “Be silent,” she said as she came into the room. “Or I shall gag you.”

She placed a rough black cloth over his eyes and tied it tightly, so it bit into his hair. The fabric smelled of lye.

“Did I not instruct you to undress?”

She had. But defiance made the proceedings far more interesting.

She jerked his shirt back by the collar and he felt a prick of metal at his nape—the cold blade of a pair of sewing shears. He heard a snip, and then the ripping of fine fabric. His shirt fell from his shoulders to pool around his thighs. And with it went the rod of tension that he carried in his neck.

He could feel her skirts brush against his skin as she tied a fist of birches into a sturdy switch. He braced, listening for the high-pitched whir as she tested it against the air.

The first stroke shocked him, though he had expected it, invited its bite. He sank his palms into the floor and arched back against the next lacerating hit.

His mind emptied.

For the first time in days, he smiled.

He closed his eyes at the relief and felt himself, at last, begin to stir.

Chapter 2

Grove Vale, Wiltshire

July 14, 1753

Opening shipping crates was not a ladylike activity. But Poppy Cavendish had precious little faith in the advantages of being mistaken for a lady.

She thrust her hammer claw around the final nail and bore down with all the considerable force her wiry body could muster. She had waited months for this particular box, stamped with its labels from Mr. Alva Carpenter across the Atlantic. She had no intention of waiting any longer.

The nail gave way with a satisfying pop. The smell of dried leaves and sphagnum moss wafted out around her. She closed her eyes and breathed it in—it smelled like musk, and earth, and opportunity.

Inside the box the trays of roots and bulbs had been packed gingerly, each item tagged with numbers corresponding to a sheet of sketches of the mature plants they would become. She willed her hands to unwrap them steadily, careful not to damage the dry, fragile cuttings that had traveled so long and so far. She held her breath as she reached the bottom of the crate.

Her hands found what they were seeking. Magnolia virginiana. At last.

The cuttings had survived the moisture and jostling of the journey across the sea and up the Thames and down the bumped and winding country roads to Wiltshire. There were eight of them here, thick, sturdy branches, their waxen leaves gone dry and dull but still intact.

She only hoped they hadn’t arrived too late.

A month ago she would have wasted no time removing the lower leaves from the branches and transplanting them to pots in the greenhouse to take root. Now that work would have to wait. She wrapped the cuttings in damp cloth and placed them in a shaft of sunlight for safekeeping. She had more pressing matters to attend to.

A life needed saving. Her own.

She returned her attention to her desk, where her fat, soil-stained ledger noted in row after odious row the impossible sums she needed to save her nursery and the improbable amount of time she had to find them.

Two weeks: the span of time her fate had been reduced to. All her dreams shrunk down into what she could cart three miles down a country road between now and the first of August.

She rubbed her eyes. No matter how she rearranged the numbers, they didn’t add up. The task before her required at least one of two things: labor or capital. But even if she somehow found the latter, the inquiries she’d made to hire temporary laborers had all come back with the same maddening answer: unavailable, due to the renovations at Westhaven. Every able-bodied soul in Grove Vale, if not the entirety of Wiltshire, had been hired away by the Duke of Westmead.

If extra men could not be hired, the nursery could not be moved, and her entire future would be at the mercy of—Stop, she commanded herself. If she let her thoughts wander in that direction, her mind would crater down a whirlpool of increasingly disastrous scenarios. She needed to focus on the tasks at hand. Her only possible salvation was in working quickly.

“Poppy.”

She whirled around. A broad-shouldered man was leaning against her workshop door, lounging against the frame with such a sense of ownership you’d have thought he had built the place himself.

“Tom!” she yelped, clutching her heart like the old crone she was no doubt fated to become. Tom Raridan’s ability to come and go undetected was his greatest talent. That he had been pulling this trick since they were children did little to lessen its ability to startle her.

“Poppy,” he said, running his eyes over her in that way that made her feel too visible for comfort. Never a diminutive man, he had grown broader in the two years he’d spent in town. Away from the summer sun of Wiltshire, his hair was darker—less the flaming shade of carrot from his boyhood, tending now toward auburn. But his smile was the same as it had been when she’d last seen him. A touch too familiar.

“I came as soon as I heard about your uncle,” he said. “You should have written to me. To think I had to hear it in the post from Mother.”

Damnation. He was right. She’d been so plunged into panic by her uncle’s sudden passing, and the chaos it had made of her life, that she’d given inadequate due to the niceties of mourning. Letters had not been sent. Customs had not been properly observed. Her uncle had been fond of Tom, and the kindly old man deserved better.

“I’m sorry, Tom. I’m afraid I’ve been preoccupied. Uncle Charles’s heir is arriving in a fortnight to take possession of Bantham Park. I’ve been in a rush to … arrange my effects.”

“A fortnight?” He whistled at the shelves of plants and cuttings all around them, the walls lined from floor to ceiling with tools and pots and sacks of seed and moss. “What are you going to do with all this?”

“My uncle left me the cottage at Greenwoods—the only part of his holdings that wasn’t entailed. I intend to move the nursery there.”

“Move an entire nursery? How do you expect to do that?”

She sighed. “With a great deal of effort.”

Tom shook his head. “You always did love an impossible task. Never the easy way for our Poppy.”

She sighed again. He was not wrong, but she had grown weary of his proclivity for commenting on matters that were none of his affair.

Not that it was only Tom who commented. She had made quite a reputation out of being impossible, though not because she enjoyed it. It was only that the so-called easy way rarely coincided with her getting what she wanted. The world was not built to suit ambitious spinsters. One had to be a rather demanding and unpopular character if one wanted a chance of success.

But even she would not have taken on such a degree of madness by choice. For years, her uncle had made it clear that he would leave her his private fortune. Only at the reading of the will had it been revealed that for over a decade Bantham Park had been unproductive.

There was no private fortune. The fate of her dreams and her livelihood would fall upon the whims of a distant cousin she’d never met. And her uncle, the dear old man she had loved and trusted beyond anyone, had somehow not found within himself the will to tell her.

“It’s too lovely a day to be in this musty old shed fretting over plants,” Tom declared, flicking her ledger distastefully. “Take a turn in the garden with me.”

She looked down at her ledger and hesitated. She had no time for leisurely strolls. But Tom could be difficult. It was easier to accede to his will and wait for him to grow bored and leave than to provoke his temper with a fuss.

“Very well. But just to the greenhouse. I must finish pruning while there’s still light.”

The path from the workshop traversed her small empire, dazzling in the summer sun. The nursery and walled gardens were bright with the blooming vegetation of July. In the field beyond, groves of fruit trees and her prized exotic saplings grew, along with row after row of English trees. Sunbeams danced from the roof of the small greenhouse, where her forced flowers basked in the afternoon light. She could scarcely believe that in two weeks’ time all this would be lost to her.

“What have I missed in Grove Vale these past months?” Tom asked, moving closer so that his arm brushed hers.

She edged away. “The renovations at Westhaven are nearly done. You should ride out to see the house. They’ve made a palace out of it. I’ve even sold them a few trees.”

He looked at her with interest. “I don’t suppose you’ve had any dealings with the duke? I have a venture that might be of interest to his investment concern. I’d give my right hand for an introduction.” He winked.

“I’m afraid my dealings were with no one loftier than the head gardener. He is quite an imperious fellow in his own right. I shudder to think what the duke must be like if his gardener has such airs.”

She glanced up at the sky. It was growing late. She needed to return to her work. “It was kind of you to come, Tom,” she said, hoping he would take the hint. “Unnecessary, but kind.”

“Poppy. For you, nothing is unnecessary.”

She chose to ignore the catch in his voice and walked more briskly toward the greenhouse, but he stopped her beneath a mature apple tree. Boldly, he took her hand and clapped it in his own.

“Allow me this liberty,” he whispered. He placed a kiss at her wrist.

Horror curdled in her gut. Of course. This was why he had taken the time to come all the way from London when a letter of condolence would have suited.

Now that she was alone, he thought he had his chance.

“Tom, please,” she objected, twisting her hand away. He moved closer anyway.

“You know why I’ve come here, don’t you? I’ve made no secret of my fondness for you. My position in London is secure—I have enough to make a life for us in town.”

He sank to his knees on the grass, a gentle, knowing smile in his eye. “Poppy. Do me the honor of being my wife.”

She keenly wished he would get up.

“You flatter me. But you, above anyone, know that I have no wish to marry.”

He grinned up at her, expectant. “You feign that you don’t wish to marry to save people thinking no one will have you. You don’t have to do that anymore. Don’t you see? You aren’t what most men want, but you are what I want. All that rig about you being a mad old spinster—I’ll turn it on its head.”

She bristled. “You will do nothing of the sort. Please—”

“Poppy, don’t be foolish. You can’t stay here alone. You can leave all these shrubs behind,” he said, gesturing at the plants she had so carefully nurtured since girlhood. “I’ll buy you new gowns. We’ll take private rooms, bring in a cook and a maid. In a few years I’ll have enough for a horse. Sooner if I can find a better place. Come to London with me. As my wife.”

“No,” she said firmly, her sympathy for the disappointment she was causing him having eroded with every sentence of his speech. “And do please get up.”

His face fell. The light behind his eyes went dull, then dark. She looked away.

“I’m sorry, Tom. Truly. And I am grateful for your friendship. But my life is here.”

He went bright at the cheeks. “Friendship. That’s what you’d call it? Because I might call it something else. Or do you spread your favors around to all your friends?”

She closed her eyes. It had been a single moment in the woods. One very brief moment, nearly five years before, when he had come to help her gather moss and she had laughed at something he had said, and he had pushed her against a tree and kissed her. And for about one half second, she had permitted it—if to permit was to freeze—before she pulled away in shock.

They had never spoken of it. But ever since that day, he had looked at her like he knew something about her that she did not.

Like he had some claim on her.

And because he was a favorite of her uncle, because he helped her in the nursery, because he sent her plants from London, she’d gone on smiling and pretending not to see it, pretending it did not seep inside her skin and rankle her from within her very bones.

She was deathly, deathly tired of it.

She inhaled, and met his aggrieved look calmly. “Tom, you have always been a friend. I hope you will remain one. But I have no wish to marry you, or anyone else. If that is why you came here, I must ask you to take your leave.”

His mouth fell open. His face clouded over with some mix of bemusement and hurt.

Her anger melted as the man took on the old, pained expression of the boy he’d once been. Poor Tom. He was full of bluster, but he was no worse than other men, and he’d been kind to her, for all his unbearable presumption.

“I know you’ll find a lovely wife. No doubt someone far more suitable than me.”

His eyes went dark and flat as glass, like those of a dog that might attack. “But you’ll not do better, Miss Cavendish. That’s a promise.” He turned and quickly walked away, his thick neck and arms huddled over his ribs as though to protect a smarting heart. She watched him go until she couldn’t bear the sight of it.

How could he so mistake her intentions? He, who had listened to all her grand plans for years? To think she would give up her life’s work—the passion into which she had poured all her efforts and every last shilling—for a flat in London and a maid? She’d more likely sail to India, or cut off her own arm and present it to Tom Raridan’s London cook to serve for supper.

What she wanted in this life was not a husband. It was freedom, finally, from dependence on men. Her entire life had been dictated by their fortunes: their deaths, plunging her from crisis to crisis; their charity, allowing her to survive, to scrape by, to make her tenuous foothold in business; their half-truths, sabotaging her ambitions. She was tired of needing permission, dispensation, kindness. She intended to be the mistress of her own fate. And there was one thing she knew with absolute certainty from observing the ways of the world: one did not get that kind of power by marrying it.

She sank back against the warm glass wall of the greenhouse and stood there for a moment, letting its heat soothe the goose bumps that had risen on her forearms despite the glare of the sun. Tom was correct about one thing. She was utterly alone now. Breathing in the loamy, balmy hothouse air, she felt it keenly. If she was to have any chance of securing her independence, she would need to find in herself the ferocious iron will that so many had accused her, not fondly, of possessing.

She waited until her hands stopped trembling and set about pruning her rows of potted plumeria—a repetitive, physical task that always helped clear her mind. The perfume of the flowers drifted around her as she worked, and she welcomed it into her lungs. She strained on her tiptoes to reach the branches of the plants on the highest shelf, humming to herself.

“Miss Cavendish, I presume?” a man’s voice said, startling her.

She lost her grip, and a plant came careening down toward her head.

The man leapt in its way, just barely blocking the pot’s impact with her nose by diverting it to land with a thump against his own shoulder. In so saving her face from the blow, he pinned her body between his larger person and the shelves in front of her. Bits of fragrant foliage stabbed at her cheek and throat. Something brushed across the back of her neck—the starched linen of the man’s cravat.

Oh, this blasted day. Had she not enough to face without uninvited gentlemen showing themselves into every last room of her nursery? Unsettling her with unwelcome suits of marriage? Assaulting her with plants?

She craned her neck to get a better look at this latest intruder, who had steadied the pot back on the shelf and was now attempting to unravel the buttons of his waistcoat from the lacings of her sturdy leather work stays.

And then she blushed, overtaken by a sudden rush of mad desire to be wearing anything—anything—other than a straw hat and a faded old gardening dress.

He was not precisely a pretty fellow, whoever he was. His nose was crooked, as though once broken, and his eyes were dark and heavy browed. But his hawkish profile, taken with his immaculate clothing, great height, and slim build, nearly stole her breath away. Had he not barged in on her and wreaked havoc on her last shred of peace on the most upsetting day of her life, she might have even been inclined to like him.

Instead, she narrowed her eyes. “Who are you, sir?”

“Archer!” a woman’s throaty, cultivated voice trilled from the doorway. “Please tell me that woman you are accosting is not our Miss Cavendish.”

The man freed his final button and stepped away, turning to the young woman with a mordant smile. “I couldn’t say. I’m afraid we haven’t had a chance for introductions.”

“I am indeed Miss Cavendish. And this is my nursery. May I be of some assistance, or have you merely come to overturn my plants?”

The petite woman sailed inside with a gracious chuckle, her hooped skirts flouncing perilously close to the fragile tendrils of Poppy’s passiflora as she walked.

“Forgive us, Miss Cavendish. My brother has such a curious approach to making introductions. I am Lady Constance Stonewell and this poorly mannered fellow is the Duke of Westmead.”

Poppy bit back a bitter laugh. Westmead. Of course. When the universe took it in mind to test what you were made of, the trials came raining down at once.

Westmead inclined his head, causing a white petal to flutter from his fine head of glossy hair. “My profuse apologies for startling you, Miss Cavendish. There was no one outside.”

“It’s a pleasure to meet you, my lady, Your Grace,” she said, making little effort to infuse sincerity into her tone. “To what do I owe the privilege?”

“You won’t like it when I tell you,” Lady Constance said, leaning in with a sparkle in her eye, as though she and Poppy shared a long history of private jokes. “You see, I understand you have had dealings with my gardener, Mr. Maxwell.”

Maxwell. Poppy nearly groaned aloud at the man’s name. He’d been after her for weeks to take on a floral design commission for a ball at Westhaven—repeatedly failing to understand that she was not a decorator, and most definitely not available. The confusion had begun when she’d made gifts of floral arrangements to a number of the larger estates in the shire, hoping the striking designs would attract more customers to her exotic cultivated plants. Along with new clients, the scheme had won her an accidental reputation as an artisan of ballroom fancies. One that was flattering, but did little to further her ambition to sell trees.

“A most persistent fellow, your Mr. Maxwell,” she said. “I’m afraid, however—”

“Evidently not persistent enough,” Lady Constance interrupted. “I’ve been quite despondent to learn his pursuit of your talents has been fruitless, for much depends on the success of this ball, and I’m told you are a genius. So I’ve come to beg. Or, failing that, to bribe you with my brother’s worldly goods.”

Westmead, she noticed, had turned his back on the conversation in order to survey the contents of her greenhouse. She took a small flicker of pride that it was not yet torn apart. Her exotics were radiant, fragrant, a riot of color and green. Nothing like the staid rows of carnations and orange trees he’d find in the middling force houses at Westhaven.

“You are kind,” Poppy said, reabsorbing herself in snipping leaves to signal that she did not have time for a long interview, “and I hate to be repetitive. But I already made clear to your Mr. Maxwell my inability to take on the commission. I am otherwise engaged, and as I have tried to explain, this is a nursery, not a floral society.”

Westmead glanced at her over his shoulder and caught her eye. “But it is a business, is it not, Miss Cavendish?”

She rewarded him with a tight smile. She disliked being condescended to. Especially by a duke.

“That is correct, Your Grace,” she said pleasantly, locking her jaw around her words like he did. Her grandfather had been a viscount, and her mother a lady; she could speak like one if she wanted to. “But I find I am unable to fulfill new commissions owing to the fact that every man in the whole of Wiltshire seems to be under your household’s employ.”

Lady Constance clapped her hands, as though this was delightful news. “But, Miss Cavendish, if labor is the issue, I would be pleased to put my brother’s resources at your disposal. I’m sure His Grace can be of assistance in whatever you require.”

Poppy gave them both her sweetest smile. “How kind. His Grace might begin by moving these to that higher shelf,” she said, indicating a row of succulents in heavy pots.

She waited, expecting her temerity to earn her a prompt rebuke, followed by the departure of her unwanted guests.

Westmead returned her smile just as agreeably. Then, he removed his gloves one by one, took hold of a tub of houseleek by his bare hands, and placed it where she asked.

His sister looked on blandly as though the sight of a duke doing the bidding of a nurserywoman were wholly unremarkable. “Miss Cavendish, do you read the London papers?” she asked.

“Not frequently,” Poppy said, enjoying the sight of the duke brushing soil from his immaculately cut waistcoat.

“Then perhaps you are unaware of my reputation for planning unholy spectacles at ungodly costs,” she said brightly, as though this description was a point of great personal pride. “Tell her, Westmead.”

“I can attest, at the very least, to the ungodly costs,” he said, picking up another plant with a wink.

“No one save for family has set foot at Westhaven for ages, and so it is very important that my guests are dazzled. I wish to transform the entire ballroom into an enchanting indoor garden,” Lady Constance continued. “Something so singular, beautiful, and lavish that every fashionable hostess on two continents will be in a frenzy to replicate it—particularly after I have it written about in every paper in town.”

She paused, and the sparkle in her eyes had hardened into a rather determined glint. “I am no expert in trade, of course, but I should think a clever woman of business might weigh whether the opportunity to exhibit her talents before the country’s wealthiest clients offers adequate incentive to rearrange her previous commitments.”

Poppy tried to refrain from glaring at the implication she was dull-witted. “My previous commitment, as you call it, is of greater value to me than the opportunity you describe. In fact, to me, it is priceless.”

At this, Westmead turned to her with a delighted grin. “But, Miss Cavendish. Nothing is without a price.”

“Your gardener already offered me triple my customary fee.”

He smiled. “I wasn’t talking about money.”

Lady Constance rolled her eyes. “Now you are in for one of his tedious lectures on business.”

“I would merely advise Miss Cavendish that a shrewd investor knows that coin is but one of many forms of currency, and often the least valuable.”

“Maybe to a duke,” Poppy could not resist saying.

Westmead chuckled. “Let’s test the theory. You mentioned you are in need of able-bodied men. How many do you require?”

Poppy put down her trowel and crossed her arms. For the sake of argument, she doubled the minimum number. “Twelve.”

“Done!” Lady Constance cried.

“Well, it really makes no difference how many men you could provide, because if I were away planting drawing room shrubberies, there would be no one here to oversee their work.”

“Unless, of course, you had a steward,” Lady Constance said. “Westmead has a frightful number of stewards wandering around. I will see you are assigned one.”

Poppy sighed. “I don’t think you quite understand. The work I am already engaged in must be completed in a fortnight, and it involves moving several acres of plants and goods three miles up an unfinished road.”

Westmead raised a brow. “Now you are making excuses, Miss Cavendish, when you should be extracting promises. A skilled negotiator must have an instinct for when to turn the screw.”

The cur was grinning at her.

She wiped her hands on her apron. She had told herself she must live up to the iron in her character. If the duke wanted to see a fierce negotiation, she would show him one.

“Very well. Here are my demands. Fifteen men, a skilled steward, and as great a sum in expenses as is required to transport my goods by the thirtieth of July. In addition, for my time and services I will require a fee of six hundred pounds to be paid in advance.”

The figure was outlandish. It could save her. No sensible person would agree to half so much.

“Very well,” Lady Constance said.

Westmead arched a brow. “Well done, Miss Cavendish. I daresay you’re learning.”

She schooled her face into the expression of a woman who did not need any lessons.

“There is one more thing I will require. A friend of mine is interested in making a proposal to His Grace’s investment concern. You’ll allow me to make an introduction.”

“A friend?” Westmead asked.

“My brother would be delighted to entertain an audience,” Lady Constance said quickly, shooting him a pointed look. “Is that not so, Your Grace?”

“Delighted,” he drawled.

“Perfect.” His sister beamed, once again the picture of sunshine and light now that she had gotten what she wanted. “Miss Cavendish, I will send a carriage to collect you in the morning.”

She extended her gloved hand.

Poppy took the only option she had left herself: she shook it.

Chapter 3

“What an intriguing woman,” Constance said as Archer helped her up onto the seat of his curricle. “Maxwell said to expect a ‘mad spinster harridan,’ but Miss Cavendish can’t be more than five and twenty. And she did not seem even slightly insane.”

He nodded, and did not add that Maxwell had also failed to mention that the nurserywoman was rather winsome. And immensely pleased with herself, judging by the smile that had toyed about her lips after he had, for reasons he could not entirely explain, goaded her into extracting a preposterous sum for a few days of work.

“I’m so glad I was able to prevail on her,” Constance continued as he climbed beside her. “I told you my arguments would persuade her.”

He smiled. “Yes. That and your six hundred pounds.”

“Well, what would be the pleasure of having the richest man in England for a brother if one can’t spend all his money on a ball he won’t enjoy at a house he never visits?”

“Anything to please my ward,” he said, urging the horses forward.

She shot him that same wry look she had been leveling at him since he first sent her to live with their aunt in Paris at the age of eight. As if to say, Yes, let’s pretend that’s how it goes. Let’s indulge in that more pleasant fiction.

He felt a pang. He had done his best as her guardian, but she was effusive and affectionate by nature, and he was ill-suited to respond in kind. Spending a fortune was a meager penance if it helped her believe he was sorry he could not be better. So was accompanying her on foolish errands, as he had agreed to do today.

He reached out and put an awkward hand to her shoulder. “I’m here, aren’t I? Doubters be damned?”

“Oh, indeed. Perfectly against your will, and utterly morose in spirit. But present? You are that.”

He shook his head. “You know, small Constance, I believe I have missed you.”

“Oh?” she said, in that bone-dry style she had learned at French court. “In spite of my provoking nature?”

“Because of it.”

She grinned at him. The air around her gave off the silvery smell of French perfume. It was the scent their mother had worn. He leaned away before she could notice that he shuddered.

They were quiet as he drove over the leafy roads that led back from Bantham Park to his family seat at Westhaven. The estate’s vast, rolling parkland was the same luminous green that he remembered from his boyhood, dotted with bales of hay and roaming sheep. As a younger man, he’d felt it unfair that his native southern England did not receive due appreciation for its bucolic glory—a landscape that rivaled the hills of Italy with its cresting downs and golden light.

He had loved this place.

Until, of course, he hadn’t.

He gazed out at the horizon, taking satisfaction at the cozy cottages and neatly tended grazing land. It was still a shock how the mud-thatched, squalid dwellings that had once blighted the landscape, and the reputation of the house of Westmead had been replaced by this scene of agrarian well-being. Equally striking was the elegant manor that now rose up from the hilltop where his crumbling family seat had moldered. The sloping eaves gave no trace of the fire that had once buckled and pockmarked the upper stories.

He handed the reins to a groom and helped his sister onto the steps, then ceded his hat and gloves to the small militia of footmen whose presence at the door never failed to startle him. In London, he lived simply, without ceremony. Here, one could not so much as scratch one’s chin without six livery-clad servants coming forth to offer up their eager fingers.

Constance perched on a settee in the center of the grand salon, perfectly backlit by sunshine streaming through a wall of windows.

“Well?” she said, gesturing at the massive gilt-spangled room that rose up around them. Light danced in air that smelled like roses. “The footmen finished placing the last of the paintings while we were out. Admit it. It’s stunning.”

He allowed her a forbearing smile. “It is, at the very least, unrecognizable.”

“That, my dear brother, was the point. Don’t you like it?”

He took in filigreed gilt work, gray-veined marble, Savonnerie carpets she’d gotten from God knew where, for God knew how many guineas. He did not like it. In point of fact, he found it rather suffocating.

“You certainly spared no expense,” he said mildly.

“Indeed I did not. If one must find a wife for a man of your disposition, one needs better tools than homespun and tallow at one’s disposal. You certainly will not be winning any woman’s hand on charm alone.”

“Your renovations are impressive. Now I must return to my study to invent ways of paying for them.”

She held up a hand to stop him. “One more thing. I’ve taken the liberty of having reports compiled on the ladies attending the ball. I think you will find them an accomplished lot.”

He sighed. “Accomplished? Constance—we discussed the kind of women you were to invite, did we not? Eager? Mercenary? Easily had?”

She wrinkled her nose in distaste. His desire to find a suitable spouse with the utmost efficiency stood in conflict with her view that matrimony should be the stuff of sentiment and poetry. On this he could not be conciliatory; it was his personal edict to avoid sentiment and poetry with the same care one avoided broken bones and plague.

“Actually,” she mused, rifling through papers on a delicate Sèvres-plaqued bonheur du jour writing desk that would not have been out of place at Versailles, “I wonder if you could look through the candidates now. If any of them are of special interest, I will assign them the best rooms.”

He sighed. “Fine.” He reached for the tea pot.

Constance immediately confiscated it from his hands and replaced it with a stack of papers. “First we have the obligatory crop of gently bred ladies. Many with titles, considerable fortune, and faultless manners. I have also included a few more spirited candidates of my own acquaintance. Beauties all, and a few are rather witty.”

He made a mental note to avoid the women on both these lists. The last thing he wanted was a wife with a fortune. She would need his own too little. Nor was intelligence an attraction. If his bride was clever, he might be tempted to like her. That would merely complicate his purpose.

What he wanted was a woman who saw him as a title and a bank vault. The kind of wife who would, when afforded certain enviable comforts, bear him an heir and not expect him to take more than a strictly legal interest in the proceedings. The kind of woman who would not require an investment of emotion he was not equipped to give.

Toward the bottom of the stack, an entry caught his eye. Miss Gillian Bastian, of Philadelphia.

“From the colonies?”

“Oh, Miss Bastian? She’s gorgeous but has the conversation of a parakeet. Her parents are so mad for her to find herself a title that I asked her out of charity. I was thinking of her for Lord Apthorp.”

A man did not come to rule the City of London without knowing an opportunity when he saw one. He closed the book. “There we are. Give Miss Bastian a nice room.”

Constance snorted. “Miss Bastian? Did you hear a word I said? I doubt you could stand her for an hour.”

“They all sound qualified. Put them in whatever rooms you like.”

Constance snatched back the reports. “Qualified. How unromantic, Archer—even for you.”

“I’m not looking for romance. I’m looking for a wife.”

She curled her lip. “You are never more His Grace,” she said, referring to their late father, “than when you profess such horrifying statements.”

Given she had hardly known their father, Archer knew she said this because she had deduced comparisons to the man were the surest way to rile his temper.

“I am marrying precisely to ensure that our tenants are spared a recurrence of the conditions that plagued them under His Grace’s stewardship,” he said, in his flattest, most arctic tone. “Never mind what should become of you if, God forbid, Wetherby gets his hands on the title.”

“Please. You are scarcely four and thirty and he must be at least sixty.”

“Smallpox does not discriminate by age.” It had taken the life of his previous presumptive heir, a distant cousin whose death at the tender age of twenty had put Wetherby in line for the title and necessitated the farce of this quest for a wife in the first place.

“It’s been a year since Paul died and you’re still with us. Surely, you can afford yourself another month or two to find a wife who actually suits you.”

“Having no wife suits me, so I’d bid you to content yourself that I’m marrying at all and find me a proper candidate for duchess. The duller and more willing, the better.”

“I’m sure you’ll get exactly the duchess you deserve with an attitude such as that. And what an awful waste.”

She left the room with a toss of her blond head.

He leaned back in his chair, grateful to be left in peace.

His sister was right. With any luck, he would get the duchess he deserved.

One who understood that marriage was a cynical pursuit. That he would invest no more in the arrangement than name, coin, and seed. Attachment—love—would not factor.

He had tried that condition once. The consequences had been such that he’d go to great lengths to never suffer them again.

He reached beneath his neckcloth and ran his fingers along the leather cord he wore around his neck. The jagged iron key it held was cool against the surface of his skin, a reminder of what hung in the balance. His salvation. His sanity. His secret, private self.

His wife would be granted more than most women could hope for: her freedom, his title, and his wealth. In return he asked only for a womb and a lack of curiosity.

For however much he was prepared to sacrifice for duty, this key would not be among his losses. He had responsibilities, after all. He required the strength to meet them.

No one need know the depths from which he drew it.

Least of all, his future wife.

Chapter 4

Her hem was frayed.

She’d only noticed now, stepping down from the ducal carriage.

Bollocks. Poppy rarely went anywhere in her good gowns, but she had considered them rather lovely. In the shadow cast by the imposing house, she suddenly saw her gray muslin for what it was: a tattered imitation of gentility.

She squared her shoulders and took a deep breath, her neck held high. After holding her own with the duke and Lady Constance, she would rather expire than seem intimidated by the immensity of their house, but it was rather difficult to remain impassive when the doors alone were three times the height of a well-built man. They swung open, revealing a phalanx of footmen and an inner atrium that would rival the royal palace for the sheer expense of its finery. It made the modest comforts of Bantham Park look like a workhouse.

“Lady Constance, Miss Cavendish has arrived,” the footman informed her hostess, who was seated at an ornate writing desk, scribbling with an intense degree of focus. Lady Constance turned, revealing that today her blue eyes were framed by a pair of spectacles. She wore a diaphanous summer gown made of a fabric so fine that it floated around her like a corona when she rose to greet Poppy. The delicate fabric was faintly smudged with the same dark ink that covered her fingertips and, here and there, her cheekbones.

“Miss Cavendish,” she said, filling the room with a smile of genuine warmth, “welcome to Westhaven. I hope you can forgive me for imposing on your time, for I wish for us to be great friends.”

Poppy curtsied, somewhat taken aback by this speech. “A pleasure, my lady.”

“Oh, do please call me Constance! We’re really quite informal here.”

“So it seems,” Poppy said, allowing her gaze to fall from the friezes along the ceiling, to the floor-length gilt-inlaid windows, to the India carpet on the floor, as soft and thick as a mattress.

“Join me for a cup of tea before we begin.” Constance gestured to a sofa upholstered in silk finer than any dress Poppy had ever owned.

“I had envisioned the garden beginning here, at the reception, such that the guests must follow the trail of greenery to the ballroom,” she said as she proffered a bowl of delicate porcelain.

Poppy looked up and felt her stomach drop. The room was the size of a modest cathedral. It would take the contents of six greenhouses to fill it.

“What an inspired idea,” she said lightly, hoping she might change the young lady’s mind once she had a better understanding of her thinking.

Constance smiled, and the expression in her eyes was not one that suggested a habit of yielding to compromise. “My ambition, Miss Cavendish, is to leave every guest agog with wonder. I hope you will let your imagination run absolutely rampant. No idea is too grand or too whimsical.”

Poppy hoped her face did not betray her mounting horror as Lady Constance led her through a colonnaded corridor to a ballroom that could easily accommodate the entire population of Grove Vale. “I do love carnations and tulips, but I hate to be ordinary. Maxwell says you are known for exotics, so I will leave it to you to dazzle us with your most unusual plants from abroad.”

Maxwell was clearly out to get her. Poppy’s nursery was known for exotics. Namely, trees. She could not very well fill a ballroom with two-year-old saplings.

“The motif will indeed need to be unusual to match the … singularity of the space,” she said, racing through her modest inventory of flowers. Her hydrangeas and roses were blooming, which was fortunate as they were elegant and durable. With more warning, she could have ordered plants from nurseries elsewhere. But with less than a fortnight, there simply wasn’t time.

She looked at Constance’s expectant face and envisioned six hundred pounds slipping through her fingers. Her throat began to itch.

“And what latitude have we to make use of the parklands?” She gestured out the window at the rolling downs and thick forest that made up the better part of Westhaven’s grounds beyond the manicured pleasure gardens.

Lady Constance laughed. “The parklands, Miss Cavendish? Do you mean to dress my ballroom in gorse and meadowsweet?”

Poppy tapped her chin, an idea flickering into focus in her mind.

“I’ve always thought there is nothing more evocative of the countryside than our beautiful native flora. The wildflowers are at their most gorgeous and romantic this time of year, and they would look remarkable in contrast with the grandeur of the ballroom. After all, without a touch of the wild, all we will have are rooms overfull with dull … ordinary flowers. Don’t you agree?”

She held her breath, hoping she had read the girl correctly.

Constance clapped her hands. “Why, it’s brilliant, Miss Cavendish! Why stop at a ballroom garden if we can have a ballroom forest?”

Poppy let out a sigh of relief. There would be plants enough to fill the rooms of Westhaven if she had to forage every last bluebell from the forest floor herself.

That left her only the next miracle to perform: finishing such a task in the unthinkable span of a fortnight.

Archer once again checked his watch, unable to concentrate on the pile of letters from London. He had spent the day riding with his land steward, an activity that reminded him why he had not returned here in thirteen years. He’d thought the estate had been stripped of the worst remnants of his father’s madness, but the obscene nymphs his forebear had erected in the grotto beneath the trout pond turned his stomach. If accidents of birth and death meant he must oversee a land he wished only to forget, he preferred to do it by correspondence.

Unfit to be alone with the kind of thoughts that kept overtaking his reports on coal prices, he went in search of Constance. The sound of laughter drew him to the library, where his sister and Miss Cavendish sat side by side in a shaft of late afternoon sunshine, their heads hunched over a sketchbook.

It struck him once again how lovely the gardener was. Like a willow tree, with her slender neck and her tumbling mass of plaited hair escaping from its pins.

“I think a bower of ivy draped over the windows in the colonnade,” she was saying. “Arranged so the leaves trail down over the glass and cast shadows in the candlelight.”

“I love it,” Constance breathed.

He leaned over them. “May I see?”