3,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

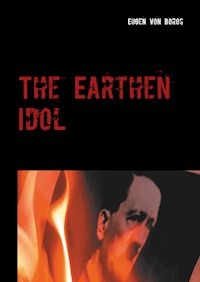

About the author: Eugen von Boros actually: Ludwig von Jeney was born on January 25, 1907 in Budapest. He studied law and economics in Munich and Hamburg and, after a short period as a writer, devoted himself to working on his Vatta estate in Hungary at the Hamburg newspaper. Since 1934 he worked on various estates, most recently in Silesia. After fleeing from Silesia in the spring, he and his family moved to Upper Bavaria for political development. The Tönerne Götze, these books, lead the reader to the time when the German Empire collapsed in the winter of 1944/45. Ludwig von Balassa and his family fled to the coming Russian armies from the east of the empire to southern Bavaria. Harrowing scenes take place on the crowded escape routes into the interior of Germany. It is only with great difficulty that Ludwig reaches the saving village on the Auerbach, in which the final tragedy of the collapse is now taking place. The general of Waffen-SS Hauser defends the place, although there is nothing left to defend. How the morale of the troop collapsed , how the SS tries to save face until the end, is masterfully described. The work was awarded a prize in 1948 by the publisher. Ludwig von Jeney died on June 28, 1948 in Pörnbach (Upper Bavaria ) from a measles disease .

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

“It was not always so miserable with us as you us on this way today

Beholding.

I am not yet used to claiming the gift from strangers.

Often reluctant to give up to the poor;

But I feel compelled to speak!"

"Goethe"

About the author: Eugen von Boros actually: Ludwig von Jeney was born on January 25, 1907 in Budapest. He studied law and economics in Munich and Hamburg and, after a short period as a writer, devoted himself to working on his Vatta estate in Hungary at the Hamburg newspaper. Since 1934 he worked on various estates, most recently in Silesia. After fleeing from Silesia in the spring, he and his family moved to Upper Bavaria for political development. The Tönerne Götze, these books, lead the reader to the time when the German Empire collapsed in the winter of 1944/45. Ludwig von Balassa and his family fled to the coming Russian armies from the east of the empire to southern Bavaria. Harrowing scenes take place on the crowded escape routes into the interior of Germany. It is only with great difficulty that Ludwig reaches the saving village on the Auerbach, in which the final tragedy of the collapse is now taking place. The general ofWaffen-SS Hauser defends the place, although there is nothing left to defend. How the morale of the troop collapsed, how the SS tries to save face until the end, is masterfully described. The work was awarded a prize in 1948 by the publisher.

Ludwig von Jeney died on June 28, 1948 in Pörnbach (Upper Bavaria) from a measles disease.

The Big Trek

The first refugee arrived in Markusdorf on a stormy January day. A small panie wagon

(Panjepferd - is a country horse with Einsat eg in agriculture and military - they were light and wiry), drawn by two shaggy horses, wrapped in the, in colorful checkered Bauer beds, sat a woman with two children. The man walked along the street in shaggy sheepskin next to the aborted animals, grumpy and silent, without looking to the side. The farmers of Markusdorf watched him move step by step along the village street. They were speechless. War? War! You knew what it was. But on that stormy January day when the first refugee reached Markusdorf, they had seen a ghost. And then there were more. No one turned to look at a trek that rolled heavily through the village and slowly, slowly disappeared into the distance. The treks became treks, entire flocks of refugees and these became a stream of people.

He clogged the country roads, rushed day and night in front of the victorious Russian army columns and rolled westward. Horses were whipped to death, fell and had to be stabbed. Infants freeze to death in the biting cold. Old people died. The food had been used up near the thoroughfares and the refugees had to make larger and larger trips in the evenings to get bread. Sometimes they slapped their ears half the night, waited for the bread in the oven and snatched it out of the baker's hand, still glowing hot. And again and again new treks came, an unmistakable stream of passenger cars, trucks, tugs, oxen and people ... people ... people.

The big trek!

Sometimes Ludwig Balassa, the lord of Markusdorf, stood in the gate and watched them go tired and taciturn; it seemed inevitable, like a natural disaster. Once the innkeeper Richter joined him, a man of honor and nodded weightily: "With man and horse and wagon ..." They stood on the street thoughtfully. They still had their home, the roof over their heads, and knew where they belonged. "How much longer?" Asked Ludwig, pointing to a pair of completely pumped-out horses that stumbled with every second step, meaning how long it would take for the poor creature, but it sounded different, more sinister: how long and the storm discharges itself through us! Richter looked gloomily at the moving columns, tired horses, tired people, above them the gray snow sky, sometimes a gust of wind that whirled up snow and everywhere restlessness, strange, unfamiliar; he hadn't heard what Ludwig had said, but made up his own mind and nodded again seriously; "That's how she hit God!"

He was a godly man. The Markusdorf manor housed over a thousand souls every night. The barns were overcrowded with returned prisoners of war, soldiers, volunteers from the East, Romanian, Hungarian, Nordic, Dutch and what kind of volunteers I know, with horses and wagons. The once so clean courtyard looked like a rubble deposit. Something lay there every night. Wooden shoes, clothing, vehicles, dishes, machine parts, straw, hay and all kinds of waste piled up. Corpses too. One day a column of political prisoners moved into Markusdorf. They had large sledges with them, each of which had twenty convicts. An SS man walked next to each sledge. It was the first transport of political prisoners that Ludwig saw and it was very different from the prisoners of war. The march of those was a leisurely stroll compared to that of political prisoners. No sooner had they arrived than the guards connected strong headlights to the light pipe and bathed the barn assigned to them in bright light. The left wing stood at the entrance to the servant's house and the prisoners pointed behind their guards' backs at their mouths and made chewing movements. The people who had come in curiously soon handed them bread and potatoes. But one of the guards had already seen it. He ran over and hit the prisoners' blue-frozen hands with a club, so that they dropped everything. Then they stood crouched in line and could not take their eyes off the bread that was within reach of the snow in front of them, and the guard stole a peek at them to see if there was anyone else to bend over. Nobody dared anymore. But at night, in the dark, they tried to get the bread in. The guard shot blind. The morning after they left, six bodies remained. The rest of them, without complaining, pulled the heavy sledges out of the courtyard, which was strewn with gravel. The sled crunched and rumbled heavily. The convicts writhed on the ropes. And the guards' whip slapped their stooped backs. Then they won the slick road. And as they left at dawn, while the bodies of the shot lay still and rigid in the snow, the cracking and clapping of the whips could be heard fading. The prisoners of war were better off when they were under the strain of the mighty

March and suffered from the poor food. Every evening they cooked for them in the large kettles of the laundry room. The English slaughtered a beef and prepared it cleanly, the French cooked a stew made of sheep meat. The Russians cut off the head of a dead horse, laughingly tossed it into hot water, and ate it with great comfort. The behavior of the guards was amusing. They had more or less made friends with the prisoners when they had endured the common inconvenience of their march through ice and snow. The strict regulations of the fixed camp could no longer be observed on the march. The Russians' guard scolded the conceited English; the accompanying team of the English considered themselves to be more noble than that of the Russians and said that the others were just a pack; and the French guard said that their prisoners had a sense of humor and a good heart, and they were happy to be able to guard the French. The prisoners of war were treated well, as far as possible, because the German soldiers who accompanied them knew only too well that they would switch roles in the foreseeable future! However, the political prisoners were escorted by the SS and the SS had nothing to lose. Her path was marked by blood and tears. Traffic flowed on the streets day and night. The old sailing instruction for circumnavigating the Cape of Good Hope: “Stop west! Always westward! “Experienced her resurrection and bloodiest repetition in those days. The inhabitants of the flat country visited each other from time to time. Everyone felt the need in the eerie silence of their rural seclusion, into which terrible news penetrated only from afar, from the major thoroughfares and the booming fronts. Hear new things, see people, speak people. One day director Hauer, Gideon Vesque and old Ranft visited Ludwig in Markusdorf. Hauser and Ranft were men who had done their lifework and are now dreaming of a quiet retirement. They wanted to sit in the sun in front of their home and watch the play of the grandchildren, they thought to smoke their Upman and to drink their Burgundy and to give young people wise anecdotes, the quintessence of their life experience. But now the wild, lively life came and swept away the idyll like the hurricane of dry leaves.

"What do you do when the Russians come?

Should I leave everything behind?

And will you be allowed to stay here at all?

I'm afraid the SS will force us to evacuate! ”Said Ranft, the owner of the beech forest. He had only recently shown Ludwig his dark-paneled dining room, the imitation rococo salon from American walnut of which he was so proud, the old porcelain plates from Napoleon's time, the oil painting of a Spanish infanta from Titian's school, the stuffed giant fox and his grandfather's pipe.

"If I had to let it all down, I'd rather shoot myself," he had assured Ludwig at the time, but at that time the Russian armies were still a few hundred miles away in Russia. In the meantime, their tops have just reached Wroclaw. Now everything looked less theoretical, the considerations became a threatening reality. The black shadows of events were already falling on them. Ranft looked at the others with his bright watery eyes, his face expressed helplessness and concern, but who should advise him?

"You have to be able to separate from earthly goods," Vesque murmured.

"What is going to happen to all of this?" Asked Director Hauer, who had worked, saved and planned all his life and completely forgot that there were other pleasures than wine, cigars and women, to see how the war was now to reap the fruits of his labor in a horrible harvest. His sly eyes, which had otherwise exuded joie de vivre and complacency, wandered restlessly from one to the other, but he did not see them, he saw the walls of his home sink in ruins. Earthly goods ... it was easy to say, but he was an old man.

"This is no longer a question of whether the front stops or not, but the only question is whether it will be possible to stay when the front approaches," Ludwig replied. Hauer, who soberly reckoned with the facts in business life, set different standards in politics, like so many Germans. He thought politics was an activity in which one worked with feelings and "sentiments".

"But we still have to have something in ambush!" He cried, chewing his cigarette excitedly and looking at Ludwig angrily and doubtfully.

"You can't lie so shamelessly!"

"Whether they're lying or still believing in their promises doesn't change the fact that the war is lost," said Vesque firmly.

The tanks will roll through Markusdorf one day, whether Hitler believes it or not, ”added Ludwig, but it doesn't take much wisdom to see that anymore.

"Anyway, I'm ready," Ranft said, drinking his schnapps and grimacing. "What use was it if you were determined not to let the events of the war drive you away and the SS would throw you out of the blue at the last minute completely unprepared!"

"Yes, do you really want to leave?" Asked Hauer in astonishment.

Want?

I'm afraid we will have to."

"I have no intention," replied Hauer firmly. "But that's just suicide!" Ranft cried urgently. "Imagine only when the artillery ruins the village, when air raids come, riots break out, the houses are looted and finally the front, rolling everything down, rolls over them! Awful! "And he grabbed his head. "You argue about things that are beyond your control," said Vesque with a calm smile, "the SS will decide this question." Hauer looked at him dejectedly.

"What am I supposed to do, old man abroad?"

Almost imperceptibly, the village was caught up in an expectant tension. A number of days had passed since the first refugee reached Markusdorf in his little car; and everyone brought something new that dwarfed the previous one . One day the last men were called up in the Volkssturm, whose leader was Ludwig's neighbor Hobrecht. Ludwig called Frau Hobrecht to find out something new.

Her husband was on the Oder and was said to be connected to some news outlets. He had left the church as an SS man, played a certain role in the district peasantry and believed more in Hitler than in God.

Incidentally - because his political obligations almost exclusively claimed him - besides, he was also a competent farmer and hunter suitable for hunting, who had raised the inheritance he had taken over from his father. He and his friend Regenau were the only large landowners in the district who had committed themselves to National Socialism with their skin and hair.

"My husband, whom I spoke to yesterday, is very confident," said Ms. Hobrecht.

"The mood of his Volkssturm is excellent." By coincidence, Ludwig had learned the day before that the Volkssturm wanted to throw away its weapons and flee as soon as the first Russian tank appeared, but he did not tell Ms. Hobrecht that. "So do you think we can stay here?"

"Well, you hope so, Mr. Balassa.

"I hope nothing more."

"But my husband said the Oder would hold until we took the appropriate countermeasures." The appropriate countermeasures! Oh, these suitable countermeasures, how often had Ludwig heard of small and big donkeys! "So?"

"However, I have already sent the children to the West."

Why?

Do you like the English?”

"The English?" Asked Ms. Hobrecht in amazement. "Do you think that the West will not be occupied, madam?" "No, why?" Asked Mrs. Hobrecht stretched. "Because it will also start soon in the West." "But we have only recently launched a counteroffensive and this is progressing well!"

"You say."

"Don't you believe it?

Do you think we won't win the war?"

"Don't win ... what a lovely description for the defeat!"

No, Ludwig really didn't think the war could still be won. There was a short, meaningful break. "I will call you in any case if I should hear something new," Mrs. Hobrecht concluded the conversation briefly. She despised Ludwig a little because of his small faith.

"Thank you very much, madam, that" all cases "are coming!" But Ms. Hobrecht could no longer call Ludwig, the private telephone service was stopped shortly thereafter. So that everyone in his village, like an island, was cut off from the world and its events. Only radio broadcasted the connection with the enormous events of the time. And he brought little good; it was also a somewhat questionable news source. The refugees told all the more . The news of Job increased. City after city fell into the hands of the advancing Russians.

But where was the German army?

Where were the countermeasures promised in big words?

Many wondered. There was no sign of a deployment, no tanks, no guns, no infantry, only smaller units fleeing westward. On the morning of a windy January day, the old Ranft sent a messenger to Ludwig with a letter in which he wrote that his son had sent him a message that the Panzer Corps Greater Germany had just passed through Liegnitz and everything was about to change. On the same day Ludwig told another acquaintance that his nephew had been able to reach him by phone (he had simply registered for a Wehrmacht call because most of the telephones had already been turned off) to calm him down. He should neither pack his suitcases nor prepare for departure; new weapons would be used and the situation would change fundamentally. And the day after, when he came into the cowshed, Ludwig's people beamed with joy, now that the evil spook was over, they didn't have to come from the house and the yard, because the Fiihrer had sent a message to the German people that the long-awaited and so often predicted turn for the next forty-eight hours promised.

"God forgive me the last twenty-four hours of this war!" He should have said. "The last twenty-four hours, they will be terrible for the enemy!" So fear and hope drove strange flowers. Ludwig looked at the sky, stunned by so much trust and stupidity. The Russian advance continued. Cities near the front were bombed. The sky was full of "Christmas trees". The muffled rolling of the bombs was heard, for most of them a strange, ominous sound, since Silesia had until then been almost spared from air strikes.

The people stood in the street, opened their eyes in fear and stared at the suddenly illuminating, sparkling, flashing sky, the sublime calm of which had now come to an abrupt end. "We will experience more, people," said Ludwig calmly.

"My God, my God!" They muttered as if the world was going under and standing still and looking and staring as a trek creaked and clanked past them. Because the flow of refugees did not stop, it became even more powerful. Russian low-flying aircraft chased out of the snow clouds, firing at pulling colonies from the Wehrmacht or what they believed to be, and trains at train stations.

When the wind was favorable, you could already hear the thunder of cannons, which increased hour by hour in the coming days until it got so strong in the last two nights that the windows trembled and you woke from your sleep.

The front of Markusdorf was approaching more and more, but nothing was known. The villagers eagerly awaited the daily Wehrmacht report. Man does not like to hear what he does not want to hear; but better bad news than no news at all. There was a lot of talk on the radio about heroism, endurance, countermeasures and final victory. The turning point, the big turning point, was supposedly imminent! Ludwig wondered, while he was aware of the task of newer cities and the loss of further lines of defense, whether there were really people in Germany who believed in this turn. There really were still such! You spoke of the new, upcoming Tannenberg as a fixed fact with a confidence that already bordered on narrow-mindedness. Ludwig also followed the reports of the High Command of the Wehrmacht, but not in the hope of a fundamental change in the situation, but only to know what they were up to.

Although he was completely convinced that everything that the leadership allowed the comrades to know, at least as far as the military events were concerned, was largely true, he was also aware that some things were delayed and many things was completely suppressed. As always and everywhere in the Third Reich, you had to be able to read between the lines. The situation was threatening enough after the advance of the red army in Markusdorf in the north. All they had to do was advance from the south and they were trapped like a cat in a sack, in a sack from which there was no escape. Ludwig had always listened to foreign channels. It was on the prison and the death penalty in severe cases, but in the unrest and uncertainty of the past few days people with a more delicate conscience than Ludwig had no longer bothered with the orders of the party. The water was up to your neck. Everyone wanted to know only one thing: what you were at; and you could only do that if you watched the reports from foreign channels carefully. Everyone was already doing it openly.

Where did the Russians stand?

That was the only question that still interested. When the first refugees arrived from Wroclaw, Ludwig called his people together, divided wagons and teams, and determined the coachmen who had to take care of their wagons. The wagons were covered with tarpaulins, the horses were freshly shod, the axles were lubricated and everything was made available for a trek. However, since nothing was moving in the village and Ludwig was afraid that at the last moment a big mess could arise and the cars would be stormed . Ordered he mayor and local peasant leader to be to no man cared with them to discuss how everything should take place, because official from this appointed positions around the organization of the evacuation.

"The party is of the opinion that the front will soon come to a standstill, at the latest on the Oder. But not only that, we will start a counterattack again, ”Consul General Sünting said to Ludwig. It was one of the few coolthinking people who had soberly and clearly judged the prospects of war, except perhaps at the moment when the campaign in France had ended victoriously; but at that time everyone in Germany was an optimist and saw the situation through rosy glasses.

Despite his pessimistic view of the possibilities, the general consul was struck by lightning when the catastrophe occurred.

"They pretend that everything is in perfect order and then tell us a few hours before the front arrives that we have to leave our houses," replied Ludwig bitterly, "but then there will be no district leader nearby that people could kill out of gratitude. ”For the evening of the same day, Ludwig had the whole community called to Richter's inn to arrange for the evacuation. He was just about to determine the cars and tension in the village when the door was opened and a woman rushed in: "The Russians came across the Oder at Auras!" The people jumped up, they wanted to be on the street, they already thought to hear the roar of the tanks. Ludwig had trouble calming her down.

The woman who had brought this news was standing in the corner at the counter. Her hair was tangled in her face and she, waving her hands wildly, told details about Wroclaw's evacuation.

“Thousands are still standing at the train stations while the enemy armored pens are already fighting in the suburbs . The streets are littered with brown uniforms, Hitler flags and party books, but the party's men have disappeared. The Gauleiter, who has executions every hour in front of the town hall, cannot change that. But no one cares about women and children! You would have to kill every party boss like a great dog!”

And a shudder of horror ran down those people who hadn't even dared to have such blasphemous plans.

"Just wait until you have to get out too!

Out into the cold, into the snow, without a home, without food!

And everything stays put!

Then you will think differently. O this cursed gang!

God punish them for it!"

Ludwig still managed to announce how the evacuation of Markusdorf should proceed, so that he could face this difficult day with a certain reassurance.

The next day, the local group leader Ludwig made a serious reprimand. He should please refrain from worrying the population. It was not to be thought of that their area had to be cleared, because the Oder hold, they hold like steel. The Russians were thrown back again. When Ludwig was informed of this by Poleschner, who was also mayor, Ludwig said: “The Oder will hold as the Dnieper and the Vistula held. Have everything prepared for an emergency!"

"The local group leader is a donkey to say with respect," replied Poleschner from the bottom of his soul, "he can't even write properly." He had to pluck some secret little chicken with the local group leader. He was block leader of the party and mayor of Markusdorf, but not a hero. People occasionally enjoyed telling an episode from the so-called fighting period when the hall battles in Germany were still raging. Poleschner was always eager to ride, but when the fierce fighters took off their skirts to storm a gathering, he was always invisible.

"But, people, people ... somebody has to stay with the things!" If every party member was asked with the worsening of the situation, he should be a burning torch of resistance, (big words were very popular), thank you most for it. S he wanted to be no heroes who perished with Waving flag, not martyrs Hitler; they were simply people who wanted to save their precious lives in this collapse of gigantic proportions and a lot more.

The prediction of the local group leader Thon did not seem to be true, because the refugee misery worsened by the hour. There was no longer any bread to be found in Kostenblut, the next market town. Dead children, dead horses, broken vehicles lay around in the market square.

At times the crowds on the west-facing road were so strong that hardly any pedestrians could get through.

The coachman Teuber, who had continued to drive refugees from Markusdorf at six o'clock in the morning, was women with infants who had come from Wroclaw on foot and who were passed on from place to place by horse and cart; Ludwig told on his return that he fas s t all the way in the field next to the road down was what was possible only with the light sledge. On the outward journey, he found the vehicles of a trek from the blood of costs; they had only covered about two kilometers during the day. The situation now gradually seemed to the settler Thon, local group leader of the party, and he convened a meeting in Kostblut.

The meeting room, the old brewery, was overcrowded. The peasants stood together in small, heated groups, smoking terrible penetrating, homemade tobacco, clearing their throats and blinking.

The Catholic and conservative bloodstream has always been a reactionary. When a party speaker mocked the church at a meeting a long time ago and contemptuously ignored the calcified old people of the terrible system era and the stupid heads without character and energy that led the neighboring states, he faced a wall of icy silence. Now that the party and the world it had created was falling apart, they no longer intended to remain silent, but to express their opinions rather forcefully. The local group leader came and walked through the ranks of the self-confident peasants of the blood, who were watching him, mumbling under his breath; but no hand rose to the hated Hitler salute. Then, in accordance with the instructions he had received from the Neumarkt district leader, an insignificant, pale young man, he tried to explain the situation in order to deal with emergencies - how often did you hear this expression in those days! - take all safety measures.

"Party members!

And comrades!

The hour ... the hour is serious!"

B egann Thon somewhat choppy, because he was not a great orator and he was sitting across the silent crowd - skeptical, dismissive, mocking.

“A serious hour requires serious action. That is why all men are captured in the context of the Volkssturm ... they are set up and placed in the fighting front. Every step of our beloved homeland is defended to the last drop of blood, yes ... Every house is a fortress! Every courtyard is a castle, a castle of faith and loyalty to our beloved guide. Yes ... and each of us grab our rifle!"

The unusual effort of talking drove the local group leader to sweat. He pondered for a while where he left off and how his memorized text continued at home.

The farmers looked at each other and grinned. Ludwig was sitting in the front row, his eyes fixed on the speaker, on the swastika flag on the wall and the cheap print that represented Hitler.

His lips curled mockingly.

"The storm surge of the a ... a ... Asian hordes that are flooding old Europe and threatening to destroy our timehonored culture will find a breakwater in us!" The local group leader fell silent to take a breath.

"Ironically in cost blood!" Someone called loudly.

The farmers clinked glasses and laughed. The settler Thon continued threateningly and emphatically: "Every farmer, every farm worker and every comrade in general ... take a rifle!!

Nobody is too good to defend the fatherland!

Whoever pushes himself will be shot!

Whoever flees will be shot!

Those who leave our ranks exclude themselves from the national community ... "... and will also be shot!" The voice called again and the farmers laughed out loud.

"I'm not kidding, comrades!

Comrades!

Rest there in the corner!

The last is now valid!"

"Party comrades in front!" Cried one farmer, applauding the others. The local group leader looked helpless and angry at the same time. He considered for a moment whether he should have the caller arrested; half a year ago he would have done it safely. Yes, half a year ago! Then he continued undeterred. “We have to give up our last, yes! Everyone is now assigned his place, which he has to defend with a rifle and bazooka!”

The peasants liked this less and they scowled.

"We stand here, a rock in the surf. And where the German soldier is, there is no room for the enemy. ”The large farmer Nonnaster believed that Thon had chatted enough and asked him when all of this was supposed to happen. Well, if the Russians were combing, of course, Thon enlightened him and beckoned him to sit down; it was far from over. But Nonnaster stopped and persistently asked him if they would do anything after the withdrawal of the Wehrmacht, because that was how he understood it, but maybe he was wrong.

"Wehrmacht! Wehrmacht!

What does the Wehrmacht concern us!

We report directly to the party, ”Thon cried proudly. "And do you think that we - a disorderly sow heap - will stop the Russian tanks from which the Wehrmacht pulled away?"

"You have strange questions, Mr. Nonnaster!" Thon stated with a dangerous threatening undertone. But the head of the local section had to regret that such threats, before which a whole congregation had recently started, did not move anymore, they had lost their effect entirely or even.

"That's not an answer!" Called Nonnaster.

"But I know you don't believe that yourself, but you think we're such idiots that we stand up to let the Russians kill us like rabbits.

But I will tell you something; we are not such idiots… no more!”

"We have nothing to talk about ... we have to act and carry out the orders which ..." "Local branch leader interrupted him angrily," if you think that we are going through this nonsense, that we stand up and play soldiers after the Wehrmacht has towered is that we fire our old shotguns so that the Russians destroy our houses, then you are extremely wrong!

There will be no more shooting here when the front goes back, ”he suddenly shouted with wild outrage and shook his fist.

"We don't let our village be put to rubble in vain!

And I tell them one thing, if someone picks up a rifle in our hands, we'll kill ourselves, understand?!"

The farmers nodded.

"The leader, our colonel ...

"The leader, our top idiot ... I tell them!

Cried No nnaster except that now was still called the man to whom they owed all their misery.

"We do what we want and you ... you make yourself out of the dust!"

The peasants murmured.

Thon turned angry and walked to the door, was e "Well then, so Heil Hitler!": Are mused, as if to say something, shook his head, raised his hand and called

The peasants burst out laughing. The gathering was a letdown. As the days that followed the assembly progressed, the pace of development increased. The next morning Ludwig sent a messenger to the bank in Neumarkt to get money. He came back and said there was no money. Neumarkt will be cleared. The last people are already leaving the city. The next day we heard that the smaller towns around Markusdorf were abandoned everywhere.

Ludwig then had food distributed to his people. His student Fräulein Neumann managed to get three hundred loaves of bread from an outlying baker in return for the flour. So at least everyone had some bread. They lived on these breads for the first few days of their trek.

The unrest in the village increased. Suddenly there was tobacco and schnapps.

What should you keep your supplies?

You had to leave them!