7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Universe

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

We may have eyes that look – but how clearly do we see? This compelling novel of art and adventure, Julia Grigg's debut, is set in the feverish creativity of mid-sixteenth century Italy. Francesco Bassano wants to find out how and why an extraordinary painting was made; the story traces his quest to discover the secrets of the portrait's past. Francesco's journey, his coming-of-age, takes him and his questions to Venice, Verona, Maser and Florence. Encountering the High Renaissance's masters Titian, Veronese and Vasari in the very act of creating and recording the era's stupendous art and architecture, he is witness to astonishing achievements. Enthralled, he learns of the determination needed for innovation and the sacrifices demanded of an artist if cherished ambition is to become reality. Little by little he unravels what lies behind the painting, gaining new understanding of love, truth and beauty, and of loyalty, devotion and the unbreakable bond between a master and his dogs. However, in delving deeper, the past's dark side reveals itself: cruelty, inhumanity and human frailty – and Francesco cannot avoid the experience of bitter betrayal. A spirited, entertaining fiction drawing on historical facts, The Eyes that Look is multi-sensual in its storytelling, inviting readers to revel in the unrivalled artistic riches of the Italian Renaissance.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

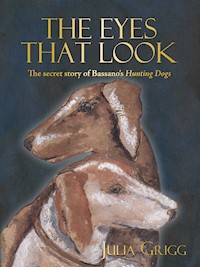

THE EYES THAT LOOK

The secret story of Bassano’s Hunting Dogs

JULIA GRIGG

For VG

The eye is more powerful than anything, more swift than anything, more worthy than anything

LEON BATTISTA ALBERTI

• • •

Dogs do speak, but only to those who know how to listen

ORHAN PAMUK

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

Francesco

25 March 1589, Casa Grande, San Canciano, Venice

The Feast of the Annunciation, blustery weather over St Mark’s basin. On a day like this, towards the end of March, the light lengthening, spring looking as though it’s decided to begin, I’m reminded of my first time in this city. 1566, I was seventeen, my first time away from home, come to get pigment for the paintings Father and I were making in the studio back up north in Bassano.

At Chioggia I marvelled at the way the land stops where the water begins, dissolves into glinting grains of sand. I’d never seen the sea before, dipped my fingers in, put them salty to my lips.

The lagoon, Venice there across it, rising right out of it. (Could it really be?) Flushed pink and gold by the setting sun’s red rays, great domes, spires pointing at the sky, almost merging with the clouds. As we neared, I stared and stared. It’s like that print of Father’s, the one by Albrecht Dürer I’ve had to copy so many times. Dürer’s city soars up, towers and turrets topped by banners streaming out in the wind, in the foreground little curly waves, a fabulous sea monster swimming away.

What I saw was like something from a fable. I’m sure I murmured my wonder out loud, asking, ‘Can this place be true?’

It’s real enough, Venice. I was soon to discover that. With hindsight, I’d caution you: the city’s surfaces may glitter but they’re rough to the touch. The Venetians, they’re real too, each of them with a story to tell. Should you be thinking of trading theirs for yours, whatever tale you’ve carried with you across the water, get yourself to the Rialto. But be ready to bargain hard.

My story began with two meetings, one expected, one not. I was to be there only ten short days – enough time though, for everything to change. Giorgio, my new friend, warned about the city too, laughing as he ruffled my hair, ‘Francesco, my lad, for an artist, nothing is ever the same once you’ve seen Venice.’ He was right.

After my first meeting, here in this mansion where so many years later I have my studio, after being ushered into the presence of Maestro Tiziano Vecellio, for me, everything did change. I was a lad from the hills, a lad who prized yellow stockings, who most likely still had sticks of straw in his hair. An audience with Venice’s acclaimed master, the master whose fame has since gone so far afield the whole world’s lauding him now as ‘Titian’ – why wouldn’t such an audience transform me?

Excruciating, it was, as it happens. Afterwards I never wanted to speak about it. How could I make anyone understand what it’s like, shedding a skin? Who shows sympathy to the grass snake struggling to slough off its old one? Who gives a care when it emerges vexed, spitting, half-blind – but newly-branded?

Then the same day, a second meeting, this one by chance. Giorgio. Signor Giorgio Vasari. If it weren’t for Giorgio would I ever have understood where inspiration comes from, about the courage innovation demands, about what has to be sacrificed if you’re to turn a vision into a reality? Would I be the person I am now?

I was green. Green. But on that day my future beckoned. I quickly learned to look at life through Giorgio’s eyes: either you’re up high on Fortune’s wheel or you’re down. In the struggle that’s our existence you’re welcome to try and force the Lady’s hand. But success? It is she who decides.

Once on my quest, it didn’t take me long to realise our fates are all intertwined. I was never alone on my journey, even when to other eyes it looked as though no one was by my side. And so, in the pages that follow it is right that mine is not the only voice to tell this story, the story that’s defined me as an artist and a man: the story of the dogs and the painting.

ONE

Francesco

CHAPTER ONE

24 March 1566, Venice

What would it be like to drown in paint, to fall right in, have it close over your head, the viscous stuff flooding your lungs, stifling your cries for help? That was the fear making my mouth dry, my legs leaden in last night’s dream – well, no, call it a nightmare. Last night, my first in Venice.

I do sometimes dream about painting, or drawing, especially when something I’m working on is difficult – but this? I was standing in a chasm, a river rushing at me, furious, foam-flecked, charging between rocks. It was red, reflecting a sky the same colour louring above. This roaring torrent, dizzying me, splashing its gore up on to my shoes, somehow I knew it was paint. Fine spray was hitting my face, so I could smell it, of course. And its hue, its particular shade of redness: it was Titian’s red.

So, even before I met him, Titian and his reds conspired to wreck my sleep. As is the way with nightmares, there was horror but no resolution and this morning, jolted into wakefulness, half of me was still there on the riverbank, teetering, unable to back away, aghast I might fall.

I’m down from the north, come with my uncle to re-supply our studio back there. The highlight of my stay? Visiting Titian. Father, planning it all, said, ‘You’ll learn from Titian. Soon as you’re off the boat, get yourself to the Santa Maria Gloriosa church. Study his altarpiece. Study it well before your Uncle Gianluca takes you to the Maestro.’

Out of earshot, I’d muttered, ‘Need I bother?’ Son of a renowned painter, grandson and great grandson of one, I thought I was sitting pretty as a Bassano of Bassano. I didn’t think about it, in fact. My fate, my future, no sweat: I’ve some talent, adequate skills to tackle what’s expected of me. An apprentice for now, yes, but with excellent prospects, entitled, heir to the Jacopo Bassano studio.

Yesterday, for the sake of keeping in Father’s good books, I went, despite how distracted I was feeling. Because Venice is distracting. At first it beguiles you, dazes you with the azure of its dancing water, the rose and gold of its shadows. Then it grabs you by the arm, pulls you in and you’re lost in the mysteries of its little alleys, bewildered to find your way barred by water, confused that the little bridges all look the same.

And the noise! Hardly had I left off gawping at the Grand Canal’s great palaces before we were on the Rialto, thrust into its uproar, its shoving, sweating stink. Whistles, cackling laughter, shouted commands, words I couldn’t catch. But anyhow, words are superfluous for some things I soon found: like the woman who licked her lips, brushed her body against my hip before pressing close, whispering. Stepping back, her smile was wicked.

Steering me past, Uncle was hissing, ‘Everything’s for sale in Venice, lad. Shop wisely.’

I soon realised how right he was. We must have passed a hundred stalls loaded with goods a thousand times more curious and colourful than the wares of any pedlar who’s ever come up to Bassano. As it turned out, Father’s advice was sound. At least for a painter. I saw Titian’s altarpiece, his Assumption of the Virgin. I studied it and I was humbled – because you could lump together all the gaudy goods ever hawked on the Rialto across all time and, truly, that painting makes a much, much braver show.

Immediately I was inside the church I could see it, far away under the east window. Closer to it, my first thought was ‘How?’ How do you imagine and then how do you achieve something so stupendous? A work over twenty feet tall. Arresting. In the foreground those stalwart men with their backs turned were throwing out their arms in astonishment. And craning their heads up to heaven, just as I was doing, straining for a last glimpse of the gorgeously robed Madonna.

The painting is an exaltation: on three planes, three workings of the colour red, heightened with the rich glow of gold towards the top. So much red, it captivates your eyes. Captivated, they have no choice but to ascend too, Titian forcing you, body and soul, to yearn for that shimmering glory. I wondered whether he’d had a plan how to achieve that effect. Or is that what this thing ‘genius’ is, something you’re possessed by at the crucial moment brush begins to stroke colour?

Father doesn’t hold with genius.

‘A modicum of talent is essential for beginning, yes,’ he says, ‘after that, it’s training. Training for the hand, but equally importantly, for the eyes. Your eyes, son, it’s what they are for. For looking.’ How many, many times have I heard it? ‘Look, boy, look. And keep on looking. Only that way will you see.’

I stood there, eyes wide and looking. Looking at my first Titian, convinced by it that Father is wrong, my conviction making me dare to dispute his teaching for the first time. In that moment, absolutely certain that a spark animating some does exist, I realised it’s those fortunate few who will lead the way, will achieve things never done before.

Casa Grande, San Canciano

Today, as a result, I’m all anticipation arriving with Uncle Gianluca at the Maestro’s mansion, a big place they call the ‘Casa Grande’. It lives up to its name. Lush lawns stretch away. There are fountains and, in one corner, a bird house where doves flutter. Not white, but dyed all colours: pink, blue, peach and pale green – imagine. The mansion has a big hall, a great, mirrored chimneypiece where a fire blazes. You can glimpse bronze statues on plinths, and down corridors there are heavy striped gold brocade curtains on windows of glittering glass. Breathtaking.

What a revelation: a painter living like this, with all the rich possessions of a nobleman, with so many servants. With adulation from the public too. Uncle and I are just two among a crowd of people, men but also women, some poor, but many fancily dressed, milling around the steps waiting to pay the Maestro tribute.

A flunkey’s white-gloved hand directs us to the studio. People dash back and forth here. There are many apprentices, those on the move harried-looking – I can sympathise with that. The ones crouched over their sketchbooks frown, peering up at a nude male posed on the dais above them. The place is very busy but very organised: through one doorway there’s a whole room just for preparing the pigments; through another, trestle tables where workers stretch canvases on to frames. It’s a powerhouse, humming with purpose, so totally different from our studio in Bassano.

Back there, it’s sober, earnest and so quiet. My younger brothers, supposed to be learning the basic skills, do their best to keep out of Father’s way, so nearly always it’s just me, alone with him.

And nothing pleases Father more than working in his studio, shabby though it is. He’d stay there all hours if he could. It looks terrible, it really does. He allows no one to touch anything, so it’s a mess. Lizards scuttle away at our approach, leaving their tracks in the dust coating the shelves where years’ and years’ worth of sketches and used-up materials are piled, all awry. A pigeon has made its nest behind one of the beams. Of an evening we hear it strut up and down, do our work to its cluck cluck clucks. First job for me in the morning is sweeping the benches free of droppings. No, no, there’s none of Titian’s sparkle and sheen for us in Bassano.

Here with the Maestro, a witness to all this grandeur, suddenly I see there are other ways to earn a living from paint, ways very different in style from ours, reaping rewards on an entirely different scale. Summoned to cross the studio’s shining marble floor to where the Maestro stands at his easel, the idea stirring in my mind brings a smile to my lips. I’m thinking, I’d like to be like Titian. I step forward jauntily.

The Maestro turns: a fierce face, grey, a corrugated forehead. He pushes a lock of hair from his temple with the back of one hand. A red-collared hound rises sleekly from near his feet, stretches, makes a great yawn. Uncle speaks our names. Titian doesn’t smile. He pats the dog’s head before extending his hand. At me, he barely glances. Instead, he thrusts forward his palette. Shoved right at me, what can I do but take it? For me to hold, huh, as though I’m one of his servants? He steps with Uncle over to the window, their shoulders and heads inclined.

Excluded, I turn to the Maestro’s easel. An Annunciation. He’s been working a blazing red. There are fat blobs of it on the palette, already I’ve got some of it on my hands and a streak on the sleeve of my best blue velvet jerkin. Mother will be furious.

I look again at the canvas: Titian’s been throwing gobbets of the colour on to the Virgin’s dress. They gleam there like fresh blood. It’s not the red in the composition that slaps me to attention, though. It’s the gold and the dazzling whiteness. It’s the burning light around Gabriel and the Virgin, light that billows out of a turbid sky broiling with clouds, cupids and a dove on outspread wings. Mary is startled from her prayers by the crack that’s split the heavens. Veil lifted but eyes cast demurely down, she looks from under her lids at the great shining archangel whose expression alerts us he brings news of some portent.

I can only gasp at the force of the image, recognising how astonishingly new and different Titian’s style is in this painting. Stock-still, staring, I hear his voice.

‘Gawping, is he, your nephew? Never seen a painting before?’

The Maestro has come close and is jutting his chin up at my face, eyes blazing. I feel his breath hot, and ugh, a fine spray of spittle.

‘Well, he wouldn’t have, would he?’ He grasps at Uncle’s arm as he jerks a thumb at his Annunciation and says, ‘Not one like this, anyway, huh? Not up there in that northern backwater where his father insists on hiding himself.’

Reaching forward and yanking the palette from my grip, his laugh is a harsh croak. He turns again to Uncle, claws again at his sleeve. ‘Became quite proficient depicting animals, didn’t he, your brother-in-law? Yes, I got one of his little works off a dealer a while ago. Bassano wanting to vaunt his skills, obviously – he’d jumbled every sort of exotic creature on to the canvas.’ He waves an arm towards the apprentices, ‘Useful for reference, at least. For my garzoni to copy, you see, the lions, the camels, etcetera.’

I wince. That’s what he’s like is he, the Maestro: no grace, just a rude old goat, full of spite? ‘Quite proficient … little works … jumbled’ what kind of comments are these about my father and our studio? Titian can say what he likes, exactly how he likes because he’s famous and rich, can he?

I don’t know where to look but somehow, I’m aware of Uncle Gianluca’s embarrassed expression, the little pursed o his lips make as he registers Titian’s contempt for my father’s achievements.

In the next moment we are dismissed. Taken aback, my uncle avoiding my gaze, I’m still fascinated and cannot break away. Uncle doesn’t move either. Inexplicable – but what we find ourselves doing: shuffling to Titian’s side as though some kind of force is keeping us there. We watch him, stooped, shoulders hunched, as he brings that damn palette so close up to his face he’s almost rubbing his nose in the colours.

Stiffening limbs, weakening sight: you would expect that, wouldn’t you, from an old man of nearly eighty? But no: Titian, grasping his brush, is at the canvas, arms up, an all-out attack. Forget weak, this old man’s strong. Strong. The force of that jabbing brush – then the daubing, then, brush rejected, he pushes at the thick colour with his fingers and his thumb, spreading it, smearing it. Could I work paint like that? My fingers tremble, wanting to.

It is then that something happens to me, me the bystander who looks on, who seethes but who also admires. Titian, this man who’s ignored me and disparaged Father, he’s hateful – but the painting he’s making, the painting is a revelation. It’s … well, it’s gawp-worthy. I’m helpless against its powerful message, so clearly articulated despite the blurred and muddied colours the Maestro’s applying with his short, chopped brush strokes, his daubing and smearing. This interpretation of his is so strong and it’s so new.

I don’t know how to describe what’s going on in my head. It’s as though I’ve been thrust suddenly awake by a bell clanging in my ears. It’s as though something is dying in me, destroyed by this first-hand evidence of the mastery and the vigour it takes to be Titian. Yet at the same time something new has begun to grow. No, it hasn’t begun to grow, it is there, sprung fully-grown into my mind. With this new thing surging through me, I feel I’m being burst open. Ambition, that’s what it is. I’m envious and ambitious and inspired, all together all at once and for the first time.

My heart thumps. I’m unsteady and my mind swirls. Plunged into Titian’s nightmare river and helpless, it’s as though I’m being swept along in its tumultuous, raging red. Red, red, as red as the blaze of anger the Maestro has made me feel. There is a roaring in my ears as the torrent takes me down. I’m going under, under.

My mind is racing: is that how you must be if you’re to have a Pope, a King, an Emperor running after you, pleading for a portrait? And that ‘spark’ I had wondered about, that must be what Titian has. Isn’t that what I’ve just seen in action? My God, I am thinking, this is how Titian has been doing things for more than fifty years: changing style, reaching for more, for perfection.

‘Come, lad. We’re leaving.’

Uncle G nudges me but my feet feel stuck to the floor. Look at this place! My eyes are not big enough to take it in. Around me, Titian’s rewards are all too plain to see: the man made rich, so rich, fame heaped on him to excess. That thought is back in my head, it has burst in again and it’s bigger now and it’s urgent: this is the place I want to be, in this great house. And the Maestro’s career, that’s the career I want.

I can’t say anything to Uncle. What will he reply anyway, if, pathetically, I ask how Titian could mock me as though I’m a dolt, could sneer so about Father? As for the envy that gnaws at me, there’s no way I can express it, nor my sense of futility – futility which borders on self-disgust as it hits home how paltry anything I’ve achieved is, set against the artistry of the man whose working practice we’ve just witnessed.

CHAPTER TWO

Fortunately, later I find someone I can express myself to, the man I had encountered earlier while waiting with Uncle G in Titian’s lobby. Giorgio Vasari: bright-faced, smiling, introducing himself as ‘author.’ A writer, the first I’ve ever met. He had offered me his hand, pulled mine to his chest, held it there in a strong grip. His cuff was of creamy lace, starkly contrasting with his badly stained hand, the knuckles blue-ish, fingertips totally black. Ink: so ours is not the only occupation to leave its mark.

His meeting with the Maestro over, Vasari was making his way out in leisurely fashion, greeting and chatting as he went.

We fell into conversation, prompted by his question, ‘And you, young man are…?’

‘Francesco, Signore. Jacopo Bassano’s son.’

‘Bassano, Bassano? Do I know that name? Let me recall what I know of it. Ah yes, something’s coming back: did I not hear that da Ponte, as he was once was, is now Bassano?’

I’d nodded. Our name change is known in Venice, then, Signor Vasari remarking how our town has followed fashion and linked Father’s artistic output to itself, ensuring it gains stature by being associated with his acclaim. ‘Yes, Jacopo. I met him here in Venice, oh, twenty-five or more years ago, I suppose it must be,’ he said. ‘He’s busy?’

Very soon I was to understand the importance for an artist of an interrogation by Signor Giorgio Vasari, the writer. The name, well, I recognised it as he said it. As, of course, would anyone who’d claim the slightest knowledge of painting or sculpture. The two Vasari volumes, we have them in Bassano. I could picture them, ancient and very yellowed on Father’s shelf: The Lives Of The Most Excellent Painters, Sculptorsand Architects. Once or twice I’d browsed the pages. Noticing he mentioned many artists of Florence but no Venetians, I had wondered why that was.

1550, Signor Vasari told me the work came out. Just a year after I was born. He quickly explained what he’s done since his first success – beginning straightaway, in fact, on a second edition to be published as a third volume, revising and expanding the first two but also including living artists. For years and years he’s been travelling all over and meeting with the artists of today to get their life stories, write them up – and rank them.

‘Thousands of miles I’ve covered and taken the details of more than two hundred artists’ biographies,’ he said. Then, a little pompously to my mind, he added, ‘I need to push on now to finish, busy though I am with endeavours of more importance to me, my painting, my architectural plans. I shall just have to dash the work off and get it on to the presses in double quick time. Can’t delay longer because people are mad keen to get my views.’

Never mind his pomposity, what he said got me thinking. ‘No one before has ever ranked artists in regard to their historical importance, have they?’ I asked. He shook his head. I was realising, yes, he had been the first to contrast and compare artists’ different ways of working. I was thinking, this is interesting; Vasari learned about them, judged them, then found the language to describe their achievements and justify his decisions.

‘But this time it’s different because now you’re compiling living artists? And because this time you’ve come to Venice?’

Looking at me levelly, he nodded. It was dawning on me how crucial it was for Father to have his biography in this second edition of Vasari’s, to ensure his rightful place is acknowledged – and, an added bonus, to stifle Titian’s mean criticism.

And crucial for me as well. I must also be there in the book if I’m to have any chance of success in the future. Why not me too?

So, when I come away angry yet also agog from meeting the Maestro, I’m pleased to find Signor Vasari still there, gratified he invites me to go with him.

‘You want to talk? Well, come then, I’m in need of a break after quizzing the Maestro most of the morning.’

Yes! I want to hear more from this writer, what he means exactly when he says he wants to help ‘advance’ artists through his new book. So I leave Uncle G to his business at Casa Grande and follow where Giorgio leads. A gondola taking us along the Grand Canal, then we cross Dorsoduro to the Zattere on foot, where we walk head-on into chill spray blown on a bitter wind. Then Giorgio pulls me out of the grey weather to sit in the warm half-dark of a tavern by the bridge across to Campo San Barnaba. Right away he tells me, yes, I’m to address him by his first name.

Giorgio seems to like my company and with him, saying what I want to say flows easily. Perhaps I open up to him more than I should. I have to admit that all the time we’re talking it is in the back of my mind that maybe he can also help me live the way I want to live.

Giorgio goes on, all generosity about the Maestro and what he will be writing about him.

‘Ah, Titian, yes,’ he says. ‘Love him, that’s what we must do. Study him, imitate him and above all, praise him.’

Love him, that ogre? Show him, more likely.

Perhaps my expression says something or perhaps Giorgio can read my thoughts because next thing he’s jerking his face close to mine and instructing, ‘Francesco, never forget that envy’s a driving force, one you should welcome.’

Among the many things Giorgio speaks of that afternoon, uplifting things such as ‘grace’ and ‘unity’ and ‘harmony’, he declares, more than once, that his goal is the ‘betterment of the noble arts’.

I grasp on to that. Am I wrong or is he hinting there’s a way that, through his writing, he’ll better me, help me get to be where I’ve just decided I want to go? If he is, he’s cryptic. Standing up, he makes an elaborate mime of someone holding a book in his hand. Eyes rolling, languidly he flips invisible pages over. The serving girl laughs at his oddity as she passes by, laden with her clinking tray.

Then those eyes harden and flash as he darts me another question. ‘Ambitious, are you, Francesco? Best think ahead, then, think how to promote yourself.’ He taps a finger on his imaginary page. ‘Thought about what will get you noticed? You’ll need more than that winsome smile you wear so nicely, the one you beam at me so often.’ Now that finger of his is tapping my elbow, ‘Ever considered what this is for? You need to use it. Don’t ever think you can rely on someone else to push you to the front of the queue to get what you want.’

What I want? I want him to be clear. Does he mean he’ll include something favourable about Father and me in the new edition of his Lives?

Before I can ask my question, he gets his own in, ‘What’s impressed you most about Venice?’ That’s Giorgio’s thing: questions, so many of them. Often he’ll go off completely at a tangent. And laugh. Several times I suspect he’s teasing me. Or taunting.

How to reply? If I’m honest, my most lasting memory will most likely be the willowy Venetian women, their pale faces, silver-gold hair, their disturbing, swaying walk on their high, high heels. But I don’t want Giorgio to think me vulgar, so I decide to say, ‘One sight I’ll never, ever forget is those coloured stars they call “fireworks”.’

I ask if he knows who invented them. He shrugs, mutters something about ‘the Orient’.

One night out walking, I tell him, I was startled by a screeching sound and a loud whistle. Then there were streaks of light against the sky, as they went shooting, these fireworks. Then bang bang bang, the streaks burst out into red, green, blue, white. Flap flap flap, all the pigeons flew up, squawking their distress. Above, the coloured shapes, stars, spangles, snowflakes drifted silently down. The beauty of it. I opened my palms to catch one but somehow they’d vanished. There was a heavy harsh smell in the air. People threw up their arms and their caps, cheered.

Giorgio laughs his ready laugh when I tell him, ‘I was stopped dead in my tracks. My jaw must have sagged open like a true bumpkin’s.’

CHAPTER THREE

4 April, on board on the Brenta canal

All bumpkins one day have to return to the soil in which they were rooted. For me, today is that day. The wrench I felt leaving Venice was awful. In such a short a time I’ve come to care about that place so much.

Early this morning Uncle and I left from the Rialto to cross to Chioggia. I made sure to sit where I could look back all the time we were on the open water. Serene on her lagoon, half-swathed in a veil of grey-green mist, as though too shy to salute her admirers, that was how the lovely city appeared for my last view.

La Serenissima. Not serene for me, my visit. After meeting Maestro Titian and Signor Vasari, I woke every morning my head boiling with ideas. I ran everywhere in the city, trying to take it in, quickly sketching scenes I didn’t want to forget. Any spare moment I got from helping Uncle G, I hung around the places where the painters congregate. I passed over a coin for un ombra di vino and sat in a corner listening, wanting to learn as much as I could about the work such fellows do. There’s lots of it, it seems.

‘Enough for me too,’ I ask, ‘when I manage to get back here?’

‘Never fear, young sprout, we’ll find something to occupy those idle hands of yours,’ one of them told me. They discuss quite openly who has been commissioned to paint what, as well as the contract details, the price a patron’s paying. They josh and sometimes cuff each other in a jokey way when they part – but I bet that’s masking jealousy. Giorgio refers to it as ‘competition’, the contest between them to close the most prestigious deals. Clearly, it’s hot and keen.

The sun’s beginning to dip, by now Venice way back behind us. Our barge has travelled north all day on the new canal cut through the marshes. Wanting not to be here, not to be heading this way, it’s like having a bad belly ache. Ugh, going back, back to Bassano. Back to my hometown, back to the studio, back to being at Father’s beck and call.

It’ll take us a week to get there. Seven achingly slow days: the canal, the long drag through the plain, then the many winding turns of the river until finally we begin to climb into the line of dumpy little hills marking the start of the Dolomites. Edging forward, we go only as fast as the team of oxen can haul us. Their every thudding tread on the towpath dins into my head how much I’m regretting I have to go. And my anguish is added to every time I hear the crack of the bargee’s whip lashing at the poor beasts’ backs.

My uncle glances my way, concerned I’m moping, I suppose.

‘Where’s your smile today, lad?’

How can I explain? I try for a grin. ‘Uncle, if I must go home, I wish it would go faster.’

He shrugs at that, leaves me to my thoughts.

Anyway, it’s not as though I have a choice. Only at home can I get started on what I want to happen. Bassano is a backwater. The old goat Titian was absolutely right about that. No offence Father, but my future has to be in Venice. How though, am I to get that over to you?

According to Giorgio, if you’re after fame, you’ll have to wrestle it out of your fate. In that Dorsoduro tavern he said, ‘Lady Fortune’s got you, Francesco Bassano, on her wheel and is turning you no differently than the rest of us. You want special favour? You’ll need to be strong because that, she grants only to the brave.’

Well, since being in Venice, special favour, and fame to match Titian’s, those are the things I do most definitely want. And Father must be made to see that since I’m almost eighteen, I should be the one making decisions about my future. I’ll have to steel myself to ask him, ‘When am I to have a life I can call my own?’ It’s possible he has never even considered the question, just assumes I’ll follow family tradition, be under him until he dies, working on his backgrounds and staying in the background.

Before leaving for Venice I’d taken Cennino Cennini’s handbook off the studio shelf to check what he says about an apprentice’s training. Cennini writes that thirteen years are required to perfect every skill, to develop ‘real ability’. Don’t ever leave off getting practice, he says too, ‘neither on holidays nor workdays’. Ouch, so I’m to be grateful for the odd day off Father does allow.

It’s not yet thirteen years, my training. I was seven when I started in the workshop, the small jobs: fetching, carrying, bottle-washing, boiling up sizes. Now I’m seventeen. I should at least have journeyman status. I’d produce my best painting and present it to the officers at the Guild as my masterpiece. While waiting on their verdict I would pluck a sprig of white heather for luck and pray to St Luke, patron saint of artists, to take me under his protection and advance my cause.

Once my accomplishments had been recognised then I could do it: go to Venice, join the artists’ crowd, advance myself, eventually become a ‘Master’, take commissions in a studio of my own. But there’s fat chance any such plan will get Father’s agreement. I can just hear him, see that wagging finger, ‘Francesco, you’re too young for such ideas.’ But Father has to realise I must get going. If not, these ambitions of mine will come to nothing. No Father, no more time-wasting for me in backwater Bassano, no more dogsbody slaving in your shadow.

So I’ll do this, I’ll challenge him: ‘Father, let’s take Titian as a measure of whether I’m too young. How old was the Maestro when he painted his great Assumption, the one you sent me to see? Twenty.’ Yes, Father, I’m telling you, Titian was just twenty.

‘Oy – o, oi, oi,’ the bargee shouts from the stern. From either end of our craft a polesman leaps on to the towpath. The oxen halt, the men heave the ropes to moor the barge. Each night we stop like this and make a fire to cook our meal. My job is to forage for kindling.

Uncle calls, ‘Bring some green branches. Let’s get up a bit of smoke and rid ourselves us of these annoying insects.’

Coming back laden with a couple of logs and a load of sticks, I find the polesmen with a good catch in their nets. While one of them scrapes clean a battered frying pan, the other spills a mess of pinky-grey guts back into the canal. Fried fish, my mouth waters. We’ll be filling our bellies well tonight.

Turning in now, lad?’

It’s getting late but will I sleep if I go to my bunk?

‘No, Uncle G, I’ll stay on out here awhile.’ I bid him goodnight and move closer to the fire, wrap my cloak round me, lie back. We shared a flagon of ale with our supper but with all these thoughts my head is swirling as though I’ve taken grappa, gulped it down too fast.

All the thinking has come to something, at least. I’ve decided from now on I’ll be calling myself ‘artist’. Giorgio was right when he told me I should realise it’s not my grandfather’s day anymore, when someone with my skills would have been just a ‘painter’.

I’ll use the term ‘artist’, anyway, although Giorgio doesn’t. His word is ‘artificer’, which he claims combines something of the artist, something of the artisan. Complicated, to my mind. But however you phrase it, Giorgio’s opinion is that to succeed today you have to insist your work is recognised as refined, as achieving a higher level than craft, different from being a goldsmith or a carpenter.

He’s right. Take Grandfather, my namesake, old Francesco, he was always busy with something – but for most of what he did, I’m sure he received little acclaim. He could be called to work on just about anything involving putting paint on to a surface, and had no choice but to do it. Father says he remembers as a boy watching him busy as often with a signboard for a hostelry or an embroidery design for the Castle’s ladies as with an altarpiece or a fresco. That’s not the career I want.

Another of Giorgio’s questions was about patronage, ‘Francesco, tell me, how d’you define yourself – in relation to the patron, that is?’

I floundered: define myself? Giorgio, knowing exactly what he was driving at, had his thoughts off pat. He said the relationship is no longer like it used to be. Back then, before, the artist was tame, just a paid performer, because the patron’s ideas about the composition were all that counted. ‘Now it’s different. The patron comes to the artist and the artist agrees to lend his style.’

‘You mean the artist doesn’t have to do everything he’s asked to? But if he refuses, how’s he to live?’

‘Yes, right, he listens and has to accommodate as best he can the patron’s wishes, of course, because that’s his livelihood. But individuals are beginning to understand they’re entitled to act in a new way, to demand a part in deciding what the work’s to be.’ Giorgio was smiling again as he said this and then he asked me, ‘So Francesco, do you see how much better this is, better, I mean, than being just a mechanical medium through which a painting or sculpture’s achieved?’

Yes, I did see, I got it. It’s only ‘some few’ individuals though, Giorgio said, who realise they must be in charge of how their ideas are interpreted. Now I understand, that like Titian, these are the innovators, unafraid. The ones that rise way above the rest.

‘Some few’ only. Am I to be among them, surging ahead of stick-in-the-mud imitators, celebrated for a style I constantly adapt and improve?

Titian, Titian, oh no, not that name in my mind again. I can’t think of the Maestro, our encounter, without remembering my fear as that red river raged in my dream, without feeling that anger rise like bile at the back of my throat again. I can never let my father know how obnoxious Titian was to me, how insulting about him.

Despite that, I got something out of that audience. Got angry enough to want to get even with him, that’s what. I’ll make Titian realise I’m not a talentless nobody. And if that anger works like a shot of courage in my veins for when I confront Father about my independence, that’s all to the good.

I’ve stayed out here longer than I meant to. The sky’s drained of daylight and all I can see is stars studding a sheet of deep grey-blue from horizon to horizon. Clear, cloudless and no moon, just those million brilliant stars. I kick the last shards of log into the fire’s embers before launching off the bank and on to the deck. Stumbling down into the hold’s darkness, I feel around for a quilt to wrap myself in. Yes, it’s cold enough for frost, I’d say, if the temperature drops any further.

11 April, on the Brenta

Today, awake early, bedroll folded, I’m positioned for the best view as the barge rounds that bend ahead. Once beyond Cartigliano, we’ll soon at last reach Bassano. All through yesterday the tip of Monte Grappa was visible on the horizon. Almost May and yet the summit is still white. The sky glowers purple-brown in the east but a shaft of sunshine breaks through and briefly tinges the peak a delicious pink, as though the snow cap glows from inside.

My father is forever painting our mountain. Whenever he talks about his apprentice years in Venice he says it didn’t suit him there. It was too painful for him to be away from home. He missed our high country’s pure air and having sight of Monte Grappa, the grandeur of its profile, silver-gleaming in the mornings, rose-red at sunset.

From back down there in the stern Uncle waves, ‘Almost home, Francesco, only a few hours more now.’

The pastures have come on fast in the time we’ve been away. The spring wheat is rising and flattening green-gold, gold-green, rippling in the gusts sweeping over it, moving the way the muscles do under the coat of a spaniel when it’s hunting down a hare.

Ah yes, there it is, just coming into view a way upriver, Bassano, my hometown: the old wooden bridge spanning the Brenta, the tall yellow and brown houses stacked down the slope, the castle jutting up proudly to the east. And looming over it all, barricading us in from the ice-capped ranges to the north, the dark bulk of our great mountain.

All very handsome but all very dull. Nothing will have changed there, that I can guarantee. I suppose there’s no reason it should have, just because for the first time in my life I’ve been away for three weeks. Anyway, I won’t be staying long. Yes, I’m going to move on, I have to. My plans, Father, somehow you’ve to be persuaded to hear them. What is the trick that will get you to let me go my own way?

CHAPTER FOUR

11 April, at the house by the bridge, Bassano

‘Only the best reds and blues, remember,’ Father had said before we left. ‘Vermilion red especially, and the purest lapis lazuli. And this time I’m after a lot.’ As always, he was concerned about getting value for money. His fist clenched over the coins he’d just counted out in his palm, he shook it by my ear so I heard their jingling while he warned me against Venice’s cutthroat merchants. ‘Hard, those men, hard, Francesco. Their arms will need a proper twisting before you’ll squeeze a reasonable price out of them.’

I have to grin, remembering my tall father, who almost never jokes, contorting himself to mimic a merchant bent double and squirming, his elbow yanked behind him, mouth opening and closing silently as though screaming.

Only thanks to Mother secreting me a small purse did I have anything at all to spend in Venice. And as for the blue scarab ring on my middle finger, that I’d better swivel round into my palm. If Father spots it, it’ll surely qualify as an extravagance. Were I to tell him the truth, that no money changed hands – no, I tossed a lucky dice, won it playing cards – well, that would not excuse me in his eyes.