The Fierce Light E-Book

13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Contains a selection of prose and poetry from 38 contemporary British, Australian and New Zealand writers who fought during the Battle of the Somme. This work tells the stories of different men from different backgrounds.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2006

Ähnliche

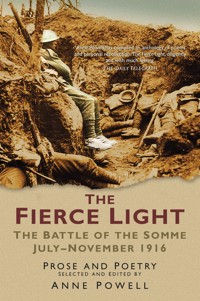

The

Fierce Light

The Battle of the Somme

July–November 1916

In Memory of my Grandfather

Major William Digby Oswald, D.S.O.

(5th Dragoon Guards)

mortally wounded at Bazentin Ridge

14th July 1916

Commanding

12th Battalion West Yorkshire Regiment.

and

for my first three Grandchildren

Edward, Amelia and Molly

with the hope that they, and their generation,

may inherit and safeguard a world of

Peace, Tolerance and Love.

The

Fierce Light

The Battle of the Somme

July–November 1916

PROSE AND POETRY

SELECTED AND EDITED BY

ANNE POWELL

First published in 1996

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

© Anne Powell, 2006, 2013

The right of Anne Powell to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 9616 0

Original typesetting by The History Press

CONTENTS

Alphabetical List of Authors

Introduction

JOHN STEWART: Major, 8th Battalion Border Regiment

Poems: On Revisiting the Somme

JULY 1916

WILLIAM NOEL HODGSON: Lt., 9th Battalion Devonshire Regiment

Poem: Before Action

CECIL LEWIS: Flt. Lt. Royal Flying Corps

From: Sagittarius Rising

EDWARD LIVEING: 2nd Lt., 1/12th Battalion London Regiment (The Rangers)

From: Attack

GEOFFREY DEARMER: Lt. 1st/2nd Battalion (Royal Fusiliers) London Regiment

Poem: Gommecourt

Poem: The Somme

GERALD BRENAN: Captain, VIIIth Corps Cyclists Battalion

From: A Life of One’s Own: Childhood and Youth

FRANK CROZIER: Lt. Colonel, 9th Battalion Royal Irish Rifles

From: A Brass Hat in No Man’s Land

ROWLAND FEILDING: Captain, 1st Battalion Coldstream Guards

From: War Letters to a Wife: France and Flanders 1915–1919

CLAUDE PENROSE: Captain, Attached 4th Field Survey Company, Royal Garrison Artillery

From: Poems and Biography

Poem: On the Somme

SIEGFRIED SASSOON: 2nd Lt., 1st Battalion Royal Welch Fusiliers

From: Diaries: 1915–1918

From: Memoirs of an Infantry Officer

Poem: At Carnoy

Poem: A Night Attack

ROWLAND FEILDING: Captain, 1st Battalion Coldstream Guards

From: War Letters to a Wife: France and Flanders, 1915–1919

DAVID JONES: Private, 15th (1st London Welsh) Battalion Royal Welch Fusiliers

From: In Parenthesis

LLEWELYN WYN GRIFFITH: Captain, 15th (1st London Welsh) Battalion Royal Welch Fusiliers

From: Up to Mametz

Poem: The Song is Theirs

CYRIL WINTERBOTHAM: Lt., 1st/5th Battalion Gloucestershire Regiment

Poem: The Cross of Wood

GILES EYRE: Rifleman, 2nd Battalion King’s Royal Rifle Corps

From: Somme Harvest: Memories of a PBI in the Summer of 1916

GRAHAM SETON HUTCHISON: Captain, 33rd Battalion Machine-Gun Corps

From: Warrior

CHARLES CARRINGTON [EDMONDS]: 2nd Lt., 1st/5th Battalion Royal Warwickshire Regiment

From: A Subaltern’s War

ROBERT GRAVES: Captain, 2nd Battalion Royal Welch Fusiliers

From: Good-bye To All That

Poem: A Dead Boche

GERALD BRENAN: Captain, VIII Corps Cyclists Battalion

From: A Life of One’s Own: Childhood and Youth

ROBERT GRAVES: Captain, 2nd Battalion Royal Welch Fusiliers

From: Good-bye To All That

Poem: Bazentin, 1916

FRANK RICHARDS: Private, 2nd Battalion Royal Welch Fusiliers

From: Old Soldiers Never Die

SIEGFRIED SASSOON: 2nd Lt., 1st Battalion Royal Welch Fusiliers

From: Diaries: 1915–1918

Poem: To His Dead Body

FORD MADOX HUEFFER: 2nd Lt., 9th Battalion Welch Regiment

Poem: The Iron Music

EWART ALAN MACKINTOSH: Lt., 5th Battalion Seaforth Highlanders

Poem: Peace Upon Earth

Poem: Before the Summer

ADRIAN CONSETT STEPHEN: Lt., Trench Mortar Battery, Royal Field Artillery

From: An Australian in the R.F.A.: Letters and Diary

AUGUST 1916

EWART ALAN MACKINTOSH: Lt., 5th Battalion Seaforth highlanders

Poem: To the 51st Highland Division: High Wood July–August 1916

Poem: High Wood To Waterlot Farm

RAYMOND ASQUITH: Lt., 3rd Battalion Grenadier Guards

From: Raymond Asquith: Life and Letters by John Jolliffe

MAX PLOWMAN: [MARK VII] 2nd Lt., 10th Battalion West Yorkshire Regiment

From: A Subaltern on the Somme in 1916

Poem: Going into the Line

LESLIE COULSON: Sergeant, 1st/12th Battalion London Regiment (The Rangers)

Poem: The Rainbow

ALAN ALEXANDER MILNE: Lt., 11th Battalion Royal Warwickshire Regiment

From: It’s Too Late Now: the Autobiography of a Writer

GRAHAM GREENWELL: Lt., 4th Battalion Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry

From: An Infant in Arms: War Letters of a Company Officer 1914–1918

ADRIAN CONSETT STEPHEN: Lt., Trench Mortar Battery, Royal Field Artillery

From: An Australian in the R.F.A.: Letters and Diary

FRANK RICHARDS: Private, 2nd Battalion Royal Welch Fusiliers

From: Old Soldiers Never Die

FRANCIS HITCHCOCK: Captain, 2nd Battalion Leinster Regiment

From: “Stand To”: A Diary of the Trenches 1915–1918

ROBERT VERNEDE: 2nd Lt., 3rd Battalion The Rifle Brigade

From: Letters to His Wife

FREDERIC MANNING: Private, 7th Battalion, King’s Shropshire Light Infantry

Poem: The Face

GRAHAM GREENWELL: Lt., 4th Battalion Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry

From: An Infant in Arms: War Letters of a Company Officer 1914–1918

FRANCIS HITCHCOCK: Captain, 2nd Battalion Leinster Regiment

From: “Stand To”: A Diary of the Trenches 1915–1918

SEPTEMBER 1916

FRANCIS HITCHCOCK: Captain, 2nd Battalion Leinster Regiment

From: “Stand To”: A Diary of the Trenches 1915–1918

ROBERT VERNEDE: 2nd Lt., 3rd Battalion The Rifle Brigade

From: Letters to His Wife

Poem: At Delville

EDMUND BLUNDEN: Lt., 11th Battalion Royal Sussex Regiment

From: Undertones of War

Poem: Preparations for Victory

Poem: Escape

Poem: The Ancre at Hamel: Afterwards

Poem: Premature Rejoicing

Poem: Thiepval Wood

THOMAS MICHAEL KETTLE: Lt., 9th Battalion Royal Dublin Fusiliers

From: The Ways of War: With a Memoir by His Wife

Poem: To my Daughter Betty, The Gift of God

FATHER WILLIAM DOYLE, SJ: Attached 8th Battalion Royal Irish Fusiliers

From: Father William Doyle, SJ: A Biography by Alfred O’Rahilly

RAYMOND ASQUITH: Lt., 3rd Battalion Grenadier Guards

From: Raymond Asquith: Life and Letters by John Jolliffe

ROWLAND FEILDING: Major, 6th Battalion Connaught Rangers

From: War Letters to a Wife: France and Flanders, 1915–1919

EDWARD WYNDHAM TENNANT: Lt., 4th Battalion Grenadier Guards

From: A Memoir by Pamela Glenconner

FATHER WILLIAM DOYLE, SJ: Attached 8th Battalion Royal Irish Fusiliers

From: Father William Doyle, SJ: A Biography by Alfred O’Rahilly

ARTHUR CONWAY YOUNG: 2nd Lt., 7th Battalion Royal Irish Fusiliers

From: War Letters of Fallen Englishmen

EDWARD WYNDHAM TENNANT: Lt., 4th Battalion Grenadier Guards

From: A Memoir by Pamela Glenconner

ARTHUR GRAEME WEST: Captain, 6th Battalion Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry

From: The Diary of a Dead Officer

ALEXANDER AITKEN: 2nd Lt., 1st Otago Battalion (New Zealand Expeditionary Force)

From: Gallipoli to the Somme: Recollections of a New Zealand Infantryman

ADRIAN CONSETT STEPHEN: Lt., Trench Mortar Battery, Royal Field Artillery

From: An Australian in the R.F.A.

OCTOBER 1916

LESLIE COULSON: Sergeant, Attached 1st/12th Battalion London Regiment (The Rangers)

Poem: But a Short Time to Live

Poem: From the Somme

Poem: Who Made the Law?

EDMUND BLUNDEN: Lt., 11th Battalion Royal Sussex Regiment

From: Undertones of War

FRANK RICHARDS: Private, 2nd Battalion Royal Welch Fusiliers

From: Old Soldiers Never Die

FREDERIC MANNING: Private, 7th Battalion King’s Shropshire Light Infantry

Poem: Transport

Poem: Grotesque

Poem: The Trenches

Poem: A Shell

Poem: Relieved

MAX PLOWMAN: 2nd Lt., 10 Battalion West Yorkshire Regiment

From: A Subaltern on the Somme in 1916

Poem: The Dead Soldiers

NOVEMBER 1916

EDMUND BLUNDEN: Lt., 11th Battalion Royal Sussex Regiment

From: Undertones of War

Poem: At Senlis Once

FRANK RICHARDS: Private, 2nd Battalion Royal Welch Fusiliers

From: Old Soldiers Never Die

GRAHAM GREENWELL: Captain, 4th Battalion Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry

From: An Infant in Arms: War Letters of a Company Officer 1914–1918

SIDNEY ROGERSON: Lt., 2nd Battalion West Yorkshire Regiment

From: Twelve Days: The Somme November 1916

EDMUND BLUNDEN: Lt., 11th Battalion Royal Sussex Regiment

From: Undertones of War

EWART ALAN MACKINTOSH: Lt., 5th Battalion Seaforth highlanders

Poem: From Home

Poem: Beaumont-Hamel

Poem: Beamont-Hamel: November 13th, 1916

DAVID RORIE: Captain R.A.M.C. (Attached 51st highland Division)

From: A Medico’s Luck in the War

ALAN PATRICK HERBERT: Lt., Hawke Battalion, Royal Naval Division

From: The Secret Battle

Poem: Beaucort Revisited

SIEGFRIED SASSOON:

Poem: Aftermath

APPENDICES:

A. David Jones – In Parenthesis – Explanatory notes

B. The Somme – List of main Battles

Maps

Bibliography

Biographical notes

Acknowledgements

ALPHABETICAL LIST OF AUTHORS

Aitken, Alexander

Asquith, Raymond

Blunden, Edmund

Brenan, Gerald

Carrington (Edmonds), Charles,

Coulson, Leslie

Crozier, Frank

Deamer, Geoffrey

Doyle, Father William, S.J.

Eyre, Giles

Feilding, Rowland

Graves, Robert

Greenwell, Graham

Griffith, Llewelyn Wyn

Herbert, A.P.

Hitchcock, F.C.

Hodgson, William Noel

Hueffer (Ford), Ford Madox

Hutchinson, Graham Seton

Jones, David

Kettle, Thomas

Lewis, Cecil

Liveing, Edward

Mackintosh, Ewart Alan

Manning, Frederic

Milne, A.A.

Penrose, Claude

Plowman, Max

Richards, Frank

Rogerson, Sidney

Rorie, David

Sassoon, Siegfried

Stephen, Adrian Consett

Stewart, John, xxiv

Tennant, Edward Wyndham

Vernede, Robert

West, Arthur Graeme

Winterbotham, Cyril

Young, Arthur Conway

INTRODUCTION

The Fierce Light is dedicated to the memory of my Grandfather, William Digby Oswald. He was born on 20 January 1880 in Hampshire and his family moved soon afterwards to Castle Hall, Milford Haven, in Pembrokeshire. He was educated at Lancing and at Rugby, where he was a distinguished athlete. He was commissioned in the 2nd Battalion Leicestershire Regiment in November 1899 and served for a few months in Egypt. During the Boer War he became Adjutant of the 3rd Battalion the Railway Pioneer Regiment, mounted infantry, stationed in outposts on the Rand. He was mentioned in despatches in 1902 ‘for rescue of a native scout on 31 January, enemy being close to him and pursued for some miles’.

On 20 February 1902 my Grandfather wrote to his parents from Reitfontein describing how his patrol had been ambushed by a party of Boers. In the ensuing skirmish the men repelled the Boers but a fellow officer was killed. My Grandfather tried to recover the body but was surrounded and captured by the Boers who after a few hours released him unscathed ‘as he was an officer and by this time unarmed’. For his part in the daylong action he was awarded the D.S.O. After the Boer War he remained in South Africa prospecting for gold. At the beginning of the Zulu Rebellion in April 1906, he joined Royston’s Horse, an elite cavalry unit, raised by the colourful Colonel John Royston. The unit consisted of just over five hundred men, ‘mostly old campaigners with faces toughened by the South African sun’. In June 1906 he was wounded in fierce bush fighting at Manzipambana after which he was mentioned in despatches, promoted to Captain and became Adjutant of the unit until it was disbanded in September 1906.

My Grandfather returned to England and in 1907 married Catherine Mary Yardley, whose home was outside Weymouth in Dorset. Two years later they went to Southern Rhodesia and lived in Bulawayo where he continued mining and where one of their three daughters was born. He returned home in May 1914 and joined the 5th Dragoon Guards as a Lieutenant on 7th August 1914; a week later he was in France as part of the First Cavalry Brigade. On 29th August, during the retreat from Mons, the Regimental Diary recorded;

‘During the morning Captain William Digby Oswald, who with a small patrol had been sent to reconnoitre north of Voyennes, came in contact with the enemy who was occupying the place and had his horse shot under him.’

During September the Regiment took part in the Battle of the Marne and the Battle of the Aisne, driving the Uhlans, the German cavalry, out of villages as they advanced. After a bridge over the Aisne was blown up on 13 September my Grandfather was sent with his troop across the river to locate the enemy guns. He got through one village and skirted another which was held by the Germans. He then hid his troop and went on with five volunteers for a short distance. He left these men behind some haystacks and crawled about a mile further on until he came near enough to note the position of several German batteries on his map. He was seen by a German patrol who opened fire on him as he ran back to the five men and his horse. They were chased until they rejoined the remainder of the troop, and although heavily shelled they eventually beat the Germans off.

By mid October the 1st Cavalry Brigade was at Ploegsteert and ‘wherever hell was hottest’ they dismounted and went into the trenches. On 31 October my Grandfather was wounded twice in the same arm during the bitter fighting at Messines and sent home to recover. He returned to France in May 1915 and formed the first Salvage Company to deal with the waste on the battlefields. Then for some months he was A.D.C. to General Haldane, commanding the 3rd Division, and fought near Ypres; he was then appointed Assistant Provost Marshal to the 3rd Division.

On 30 December 1915 my Grandfather was sent as second-in-command of the 12th Battalion West Yorkshire Regiment, camped in a ‘sea of mud’ at Reninghelst behind the Ypres salient. During January 1916 the Battalion was in and out of front line trenches and then in billets at Recques.

The Battalion was in support of the 1st Northumberland Fusiliers in the attack on St. Eloi on 27, 28 and 29 March. The German shell-fire was very heavy and the Battalion suffered many casualties; my Grandfather was buried and rescued five times. The Reverend Noel Mellish, who won his V.C. for bravery during those three days, later wrote of their friendship:

‘I admired him and loved him from the first time I met him. The first meeting was in a tiny dug-out at St. Eloi. I arrived one night looking for some men, reached his dug-out just as a heavy bombardment started, and I think in the next two hours we got to know each other. From that time I saw a great deal of him, though his regiment did not come under my charge.’

In April 1916 my Grandfather was mentioned in despatches and on 21 April he took over command of the Battalion at Meteren and for the next month was frequently in the front line trenches near Messines. At the end of May he went home on leave; on 4 June, while sailing in Weymouth Bay, he was recalled to join his men at Reninghelst as they had been ordered to the trenches again.

By the 6 July the 12th Battalion West Yorkshire Regiment had arrived on the Somme Front as part of the 3rd Division. The new front line ran from the Montauban-Longueval Road, along Montauban Alley, and then west to include most of Caterpillar Wood. On the nights of 10 and 11, when the Battalion was in the front line at Montauban Alley, my Grandfather, commanding officers of the other Battalions involved, and staff from Brigade Headquarters, reconnoitred the ground over which a surprise attack was to be made on Bazentin Ridge. During the night of the 13/14 July the troops, guided by white tapes, moved silently into position close to the enemy trenches.

At 3.20 a.m. on the 14 July, after a short, intense supporting bombardment, the attacking troops rushed the enemy trenches. The 12th Battalion West Yorkshires made good progress and found the enemy first line practically demolished. By 4.30 a.m. my Grandfather sent back a report to Brigade Headquarters that his Battalion had not only gained the enemy first line but had also reached part of the German second line. By then they had reorganised and the Battalion came under heavy fire and suffered many casualties. My Grandfather asked for reinforcements and three companies of the 1st Northumberland Fusiliers were sent forward to strengthen the attack. By 5 a.m. the West Yorkshiremen had taken the enemy second line; less than half-an-hour later another report reached Brigade Headquarters saying that the Battalion had gained all its objectives. Three hours after the attack started the village of Bazentin-le-Grand was captured, the north-west corner of the village held by the 12th Battalion. The men spent the rest of the day consolidating the positions they had gained with the loss of two hundred and fifty of their comrades. Six officers had been killed and seven wounded; forty six other ranks were killed, one hundred and seventy wounded, and twenty four were still missing.

The Battalion Medical Officer, Captain H.S. Sugars, R.A.M.C., later wrote that at about 7 p.m. my Grandfather went to the Aid Post to see as many of the wounded as possible.

‘. . . He was just going up to relieve Major Matthews who was in the new front line with the men when we heard that the Cavalry were going through. He went up to a bit of high ground just near Battalion Headquarters to see them when one of our guns – just then starting to fire from new positions – had a premature burst and he was hit by a piece of the shell driving band. The piece went right through his left lung. He did not lose consciousness but from the first he thought his wound was fatal or, as he said, ‘I am outed this time.’ The shock was of course very considerable but apparently there was not a great deal of bleeding. I had him carried all the way to the Advanced Dressing Station at Carnoy & he stood the journey very well. Just as we got there he coughed up a little blood stained sputum. He took it just as we would have expected him to. Just before I left him at Carnoy, he asked me was there any chance. I told him exactly what I thought – that if he would stay very quiet and not talk & do exactly what the Doctors wanted him to do I thought he would have a chance of pulling through. He promised me that he would do so. I had to leave him at Carnoy from where he went by motor to the main Dressing Station at Dive Copse (near Bray). On the evening of the 15th I heard he was going on very well & apparently he continued to do so till about 6 a.m. on the 16th when he became much worse. He died 2 hours later at 8 a.m. on that morning. His servant T. Pudney, who like everybody else, was very attached to him, was with him all the time. . . .’

My Grandfather was buried that evening in the Cemetery next to the Dressing Station and later Padré Mellish conducted another short service at his graveside.

On 13 February 1916 General Sir Douglas Haig, Commander-in-Chief of the British Expeditionary Forces in France, visited the 12th Battalion West Yorkshire Regiment in billets at Recques. The following day, at Chantilly, he met Marshal Joffre, the French Army Commander-in-Chief, to discuss plans for a joint French and British offensive to be launched in mid summer. The Allied aim was the decisive defeat of the German Army. The battleground chosen was the region of Northern France known as Picardy, where the River Somme flowed through a broad and winding valley northwards to the English Channel. On either side of the river banks the countryside, before 1914, was peaceful and beautiful; a patchwork of water-meadows, pastureland, orchards, woods and chalk downland, scattered with hamlets, villages, small towns, and the Cathedral city of Amiens.

The original plans were frustrated within a week when the German Army attacked the French fortress at Verdun and both sides suffered enormous losses. The resolute but hard-pressed French Army continued to hold Verdun against relentless German attacks. They looked to the British to relieve the pressure. General Haig agreed to take over part of the front line from the French 10th Army, and brought forward the date for the start of the mid summer offensive.

All through the spring the British were training in preparation for the forthcoming battle on the Somme front. The Royal Flying Corps maintained air superiority over the British lines; new trench systems were dug; roads and railways were constructed; engineers excavated long tunnels for mines to be exploded under important German strong-points; the evacuation of the wounded was planned; men and supplies were assembled behind the lines. However, the New Armies were under-strength and training was incomplete. Urgent requests to the War Cabinet for extra labour battalions had been ignored. As a consequence, men out of the trenches for a ‘rest’, were overworked on fatigue duties. General Haig was conscious of the limitations of his all volunteer army, and as the date for the launch of the offensive approached he realised that a decisive victory over the German Army on the Western Front was becoming more and more unlikely that year.

Nine fortified villages, Gommecourt, Serre, Beaumont-Hamel, Thiepval, Ovillers, La Boisselle, Fricourt, Mametz and Montauban, lay north to south on the eighteen mile front the British were to attack. Between the villages there were redoubts, dominant defensive positions, containing deep dug-outs linked by underground passages. The German front line was just forward of these strong-points with machine-gun posts cleverly positioned, many contained in the cellars of ruined houses, covering the ground over which the British would advance. Second and third defence lines had also been constructed with a series of strongly wired trench systems which had to be crossed by the British soldiers before they could reach high ground and the open country beyond. The infantry attack was planned for 29 June. The Allied bombardment opened on 24 June and, as German positions came under continuous British fire, eleven British and five French Divisions prepared for the forthcoming advance. On 28 June, because of heavy rainstorms over the previous two days, and concern that the bombardment had not achieved the success hoped for in cutting the wire in front of the German trenches, the attack was postponed for 48 hours.

By 30 June the front line and assembly trenches were packed with men confident that the artillery barrage on the German positions was sweeping a clear passage ahead. They waited huddled together in crowded conditions. Fear and apprehension strained all nerves as men prayed, looked at family photographs, joked, talked quietly or remained silent.

An early morning haze on 1 July 1916 later lifted, and the day became fine and warm. Shortly before ‘zero’ ten mines were exploded under the German trenches. At 7.30 a.m. the British and French troops rose from their trenches and ‘went over the top’. The British soldiers, led up the ladders by their Platoon Commanders, here heavily loaded. Most of them carried a weight of 66lbs of equipment which consisted of a rifle, grenades, ammunition, rations, a water-proof cape, a steel helmet, two gas helmets, a pair of goggles, four empty sandbags, a field dressing, a pick or shovel, a water bottle and a mess tin; all their movements were hampered by this great burden. As the first assaulting soldiers struggled out of the trenches, and pushed forward through the gaps in their own barbed wire, they were closely followed by further waves of men. In spite of the preliminary barrage, and the mine explosions, the Germans were ready, and their machine-guns opened fire on the British infantrymen who were mown down in their thousands. The wounded lay where they had fallen and those who survived the maelstrom of bullets moved forward across No Man’s Land towards the German front line trenches, their initial confidence in the success of the battle replaced by shock and disbelief. Throughout the morning succeeding battalions of men scrambled over the parapets in support and met the same fate.

By the end of the tragic day, the aim of a major break-through had not been achieved. Only Mametz, Montauban, and the Leipzig Redoubt had been captured by the British. Although the right-wing of the main attack, together with the French, met with moderate success, the German second-line remained unbroken. The British had suffered 60,000 casualties, almost 20,000 of whom lay dead. This number included a Newfoundland battalion at Beaumont-Hamel and the 10th Battalion West Yorkshire Regiment at Fricourt both of which were virtually annihilated.

The disaster of 1 July was caused by a number of tactical failures. The sheer strength of the German positions, and the tenacity of the defenders, had not been fully appreciated; the British ammunition in the preliminary bombardment was both faulty, and in many places ineffective, against the defensive wire and deep dug-outs; communications were greatly hampered during the intense counter shell-fire.

Cecil Lewis, serving in the Royal Flying Corps, was in the air over the front line just before the battle started. He looked down on La Boisselle as the mines exploded and the earth ‘heaved and flashed and rose up into the sky’, which he later called ‘the magnificent overture to failure’.

The Battle of the Somme continued with daily fighting and heavy casualties over the next one hundred and forty days; villages, woods and strong-points were won, lost, and won again. The fields of battle, littered with the dead, hastily constructed graves, abandoned equipment and ammunition, are immortalised in their place-names: the torn and tragic Mametz, Delville and High Woods; the shattered villages of Bazentin, Pozières, Fricourt, Ginchy, Guillemont, Flers, Courcelette, Lesboeufs, Thiepval and Beaumont Hamel; the list goes on. As the autumn replaced the summer months the relentless Allied attacks slowly dislodged the Germans from their positions and drove them back yard by yard; but the introduction by the British in mid-September of a new battlefield weapon, the tank, failed to have a marked effect on the outcome. As the weeks wore on it was evident that this had become a war of attrition. By mid November the deadlock between the two sides settled into the mud and with the onset of winter the Battle of the Somme was officially over. The exhausted British and French Armies had advanced six miles. The combined Allied and German losses were over a million men; 420,000 of these were British.

Throughout the four months men wrote of their experiences in letters, diaries and poems. Later, numerous accounts were published; some written as fiction, others as personal memoirs. The Fierce Light contains first-hand narratives and poetry by thirty-nine writers; there are no extracts from the many fine novels except for a paragraph from A.P. Herbert’s The Secret Battle at the end of the book.

The powerful and vivid testimonies are placed in chronological order of the battle and almost all describe the fatigue and danger of life in and out of the trenches; there are only a few references to rest periods behind the lines. A range of emotions and attitudes evoke not only the horror, fear and despair, but also the unique sense of humour, determination and camaraderie generated by these grim conditions. Edward Liveing and Alexander Aitken recount how they spent the hours after they were wounded; Giles Eyre and Charles Carrington describe hand-to-hand fighting in their trenches; A.A. Milne recalls Jane Austen; Edmund Blunden modestly relates the ordeal for which he won the M.C; Rowland Feilding progresses from battlefield on-looker to battalion commander at Ginchy; Father William Doyle discovered ‘two children of the same God’ lying dead side by side; Llewelyn Wyn Griffith, struggling through the tangled undergrowth in Mametz Wood, found mutilated corpses and ‘the crucifixion of youth’ everywhere; Graham Seton Hutchison, a ‘disciplined warrior’ could not explain the brilliant Cross suspended in the sky over Martinpuich and High Wood; Arthur Young and Arthur Graeme West made no secret of their fear; David Rorie remembered amusing anecdotes from his Field Ambulance Post; Graham Greenwell wrote his letters with a youthful exuberance and even after weeks of fighting still thought it was ‘a wonderful war’.

Men grieved for their comrades; felt pity for the dejected and tired prisoners; and compassion for unknown British or German fellow-soldiers whose bodies often lay unburied for days. ‘Looking on them now’, wrote Max Plowman, ‘I reflect how each one had his own life, his individual hopes and fears.’ In November Sidney Rogerson and his company struggling in trenches near the ruined village of Lesboeufs found that ‘distances were measured not in yards but in mud’; mud, by then, was ‘the supreme enemy’.

After his death on 16 July 1916, my Grandfather was mentioned in despatches and posthumously gazetted a Lieutenant-Colonel. After the War the 5th Dragoon Guards and 12th Battalion West Yorkshire Regiment erected a Portland stone seat in his memory, close to Hardy’s monument, on the Black Down hills behind Weymouth. My Grandmother chose this particular spot, which stands some 800 feet above sea level and commands a magnificent view over the rolling Dorset countryside, because they had spent many care-free days there when home on leave from Africa. The Memorial Seat is cared for and visited frequently by family and friends.

Six weeks after my Grandfather was killed his brother-in-law, a doctor in the R.A.M.C., went to his grave:

‘. . . Just before we reached the high commanding ridge where the cemetery lies – the evening sun came out & the weather cleared turning everything to gold. When we reached this crest, passing thro’ high standing grass clover – stubble & sanfoil – & turning up a covey of partridge on the way, we got into a pretty winding cart track which ran past the cemetery. Only a tiny Cemetery enclosed by a wire fence – some 50 graves – and in the midst of the 2nd row nearest the road, was dear Billy’s grave – marked by a pure white Cross of wood. I am so grateful to find him in this peaceful spot – for no more beautiful resting place could be found. Nothing but the distant roar of the guns to mar the eternal peace of it all. Surrounded by golden cornfields on the summit of this crest overlooking woods – valleys in all directions. His grave faces the setting sun. . .’

Relying on this pencilled letter, we found Dive Copse Cemetery for the first time on Armistice Day, 11 November 1975. More than twenty years after we stood at my Grandfather’s grave, the Two Minutes Silence will be observed nationally once again – as it is in France – on the appropriate day: the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month every year. This annual act of Remembrance evokes sorrow and homage to all those slaughtered, maimed and bereaved in war.

Over the years we have tramped the battlefields in all weathers and made many pilgrimages to the cemeteries and memorials on the Somme front which are lovingly cared for by the gardeners of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Built on the site of the shattered village, the great Thiepval Memorial to the Missing commemorates over 72,000 British and Commonwealth soldiers who died during the Somme battles between July 1915 and March 1918, and who have no known grave. A complete trench system has been preserved at Newfoundland Memorial Park over which much bitter fighting took place. At the entrance John Oxenham’s words exhort the visitor:

Tread softly here! Go reverently and slow!

Yea, let your soul go down upon its knees.

The suffering inflicted on both sides during the terrible months between July and November 1916 has cast a shadow ever since. Countless families still mourn. Many of the men who survived were left with physical disabilities and psychological scars. The sights, sounds and smells of the carnage and destruction haunted them for the rest of their lives. They deserve our gratitude, reverence and individual expressions of atonement; and our assurance that future generations will continue to honour them and those who lie beneath the bloodsoaked fields of Picardy.

Anne PowellAberporth1996

On Revisiting the Somme

SILENCE BEFITS ME HERE

Silence befits me here. I am proudly dumb,

Here where my friends are laid in their true rest,

Some in the pride of their full stature, some

In the first days of conscious manhood’s zest:

My foot falls tenderly on this rare soil,

That is their dust. O France, were England’s gage

The fruitful squiredoms of her patient toil,

Her noble and unparalleled heritage

Of the great globe, or all her sceptres sway

Wherever the eternal ocean runs

All, all were less than this great gift to-day,

She gives you in the dust of her dear sons.

Here I was with them. Silence fits me here,

I am too proud in them to praise or grieve;

Though they to me were friends and very dear,

I must to other battles turn, and leave

These now for ever in a sacred trust –

To God their spirits and to France their dust.

THE FIERCE LIGHT

If I were but a Journalist,

And had a heading every day

In double-column caps, I wist

I, too, could make it pay;

But still for me the shadow lies

Of tragedy. I cannot write

Of these so many Calvaries

As of a pageant fight;

For dead men look me through and through

With their blind eyes, and mutely cry

My name, as I were one they knew

In that red-rimmed July;

Others on new sensation bent

Will wander here, with some glib guide

Insufferably eloquent

Of secrets we would hide –

Hide in this battered crumbling line

Hide in these rude promiscuous graves,

Till one shall make our story shine

In the fierce light it craves.

Major John Ebenezer Stewart, M.C.8th Battalion, Border Regiment

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!