Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

The Sunday Times bestseller, launching a new trilogy in the Shades of Magic universe, an enchanting and thrilling epic fantasy from the international sensation, V. E. Schwab, perfect for fans of Samantha Shannon, Kerri Maniscalco, Leigh Bardugo and R. F. Kuang. Seven years have passed since the doors between the worlds were sealed. Seven years since Kell, Lila and Holland stood against Osaron, a desperate battle that saved the worlds of Red, Grey and White London. Seven years since Kell's magic was shattered, and Holland lost his life. Now Rhy Maresh rules Red London with his new family – his queen, Nadiya, their daughter Ren, and his consort, Alucard. But his city boils with conspiracy and rebellion, fuelled by rumours he is causing magic to fade from the word. Now Kosika, a child Antari, sits on the throne of White London. The queen leads her people in new rituals of sacrifice and blood in devotion to the altar of Holland Vosijk, summoning vast power she may not be able to control. Now Lila and Kell, living free on the waves, are charged by the captain of the Floating Market to retrieve an immensely powerful artefact, stolen by secretive forces. Now Tes, a young woman with a knack for fixing broken things, is thrust into the affairs of Antari and kings, traitors and thieves. And only her unique powers can weave the threads of power together. A triumphant return to the worlds of The Shades of Magic, The Fragile Threads of Power continues the stories of fan-favourite characters Kell, Lila, Rhy and Alucard, and introduces a new generation of magic, shadows and embers in the dark.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 975

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Sammlungen

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

White London, seven years ago

I Clocks, Locks, and Clearly Stolen Things

II The Captain and The Ghost

III The King’s Heart

IV The Open Door

V The Queen, The Saint, and The Sound of Drums

VI The Strands Converge

VII The Hand That Holds The Blade

VIII The Girl, The Bird, and The Good Luck Ship

IX The Threads That Bind

X Out of The Frying Pan, into The Fire

XI In The Wrong Hands

XII Unraveling

Acknowledgments

About the Author

ALSO AVAILABLE FROM V.E. SCHWAB AND TITAN BOOKS

The Near Witch

Vicious

Vengeful

This Savage Song

Our Dark Duet

The Archived

The Unbound

A Darker Shade of Magic

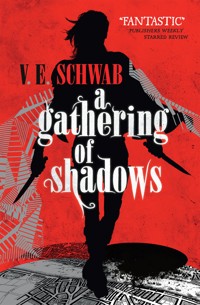

A Gathering of Shadows

A Conjuring of Light

The Invisible Life of Addie LaRue

Gallant

ALSO AVAILABLE FROM V.E. SCHWAB AND TITAN COMICS

Shades of Magic: The Steel Prince

Shades of Magic: The Steel Prince – Night of Knives

Shades of Magic: The Steel Prince – Rebel Army

ExtraOrdinary

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

THE FRAGILE THREADS OF POWER

Trade hardback edition ISBN: 9781785652462

E-book edition ISBN: 9781785652479

Signed trade hardback edition ISBN: 9781803368368

Waterstones edition ISBN: 9781803368412

Illumicrate edition ISBN: 9781803368382

Forbidden Planet edition ISBN: 9781803368399

Export paperback edition ISBN: 9781803367392

Signed export paperback edition ISBN: 9781803368375

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: September 2023

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© V. E. Schwab 2023

V. E. Schwab asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

For the ones who still believe in magic

Magic is the river that waters all things.It lends itself to life, and in death calls it back,and so the stream appears to rise and fall,when in truth, it never loses a single drop.

—TIEREN SERENSE, ninth Aven Essen of the London Sanctuary

WHITE LONDON, seven years ago

It came in handy, being small.

People talked of growing up like it was some grand accomplishment, but small bodies could slip through narrow gaps, and hide in tight corners, and get in and out of places other bodies wouldn’t fit.

Like a chimney.

Kosika shimmied down the last few feet and dropped into the hearth, sending up a plume of soot. She held her breath, half to keep from inhaling ash and half to make sure no one was home. Lark had said the place was empty, that no one had come or gone in more than a week, but Kosika figured it was better to be silent than sorry, so she stayed crouched in the fireplace a few moments, waiting, listening until she was sure she was alone.

Then she scooted onto the edge of the hearth and slipped off her boots, tying the laces and hanging them around her neck. She hopped down, bare feet kissing the wooden floor, and set off.

It was a nice house. The boards were even, and the walls were straight, and though the shutters were all latched, there were a lot of windows, and thin bits of light got in around the edges, giving her just enough to see by. She didn’t mind robbing nice houses, especially when people just up and left them unattended.

She went to the pantry first. She always did. People who lived in houses this nice didn’t think of things like jam and cheese and dried meat as precious, never got hungry enough to worry about running out.

But Kosika was always hungry.

Sadly, the pantry shelves were sparse. A sack of flour. A pouch of salt. A single jar of compote that turned out to be bitter orange (she hated bitter orange). But there, in the back, behind a tin of loose tea, she found a waxy paper bag of sugar cubes. More than a dozen of them, small and brown and shining like crystals. She’d always had a sweet tooth, and her mouth began to water even as she tucked one in her cheek. She knew she should only take one or two and leave the rest, but she broke her own rules and shoved the whole bag in her pocket, sucking on the cube as she went off in search of treasure.

The trick was not to take too much. People who had enough didn’t notice when one or two of their things went missing. They figured they’d simply misplaced them, put them down and forgotten where.

Maybe, she told herself, the person who’d lived here was dead. Or maybe they had simply gone on a trip. Maybe they were rich, rich enough to have a second home in the country, or a really big ship.

She tried to imagine what they were doing as she padded through the darkened rooms, opening cupboards and drawers, looking for the glint of coins, or metal, or magic.

Something twitched at the edge of her sight, and Kosika jumped, dropping into a crouch before she realized it was only a mirror. A large, silvered looking glass, propped on a table. Too big to steal, but still she drifted toward it, had to stand on her toes to see her face reflected back. Kosika didn’t know how old she was. Somewhere between six and seven. Closer to seven, she guessed, because the days were just starting to get shorter, and she knew she was born right at the point where summer gave way to fall. Her mother said that was why she looked like she was caught between, neither here nor there. Her hair, which was neither blond nor brown. Her eyes, which were neither green nor grey nor blue.

(Kosika didn’t see why a person’s looks even mattered. They weren’t like coin. They didn’t spend.)

Her gaze dipped. Below the mirror, on the table, there was a drawer. It didn’t have a knob or a handle, but she could see the groove of one thing set into another, and when she pressed against the wood, it gave, a hidden clasp released. The drawer sprang out, revealing a shallow tray, and two amulets, made of glass or pale stone, one bound in leather and the other in thin strands of copper.

Amplifiers.

She couldn’t read the symbols scratched into the edges, but she knew that’s what they were. Talismans designed to capture power, and bind it to you.

Most people couldn’t afford magic-catchers—they just carved the spells straight into their skin. But marks faded, and skin sagged, and spells turned with time, like rotten fruit, while a piece of jewelry could be taken off, exchanged, refilled.

Kosika lifted one of the amulets, and wondered if the amplifiers were worth less, or even more, now that the world was waking up. That’s what people called the change. As if the magic had just been sleeping all these years, and the latest king, Holland, had somehow shaken it awake.

She hadn’t seen him yet, now with her own eyes, but she’d seen the old ones, once, the pale twins who rode through the streets, their mouths stained dark with other people’s blood. She’d felt only a pang of relief when she heard they were dead, and if she was honest, she hadn’t cared much at first about the new king, either. But it turned out Holland was different. Right after he took the throne, the river began to thaw, and the fog began to thin, and everything in the city got a little brighter, a little warmer. And all at once, the magic began to flow again. Not much of it, sure, but it was there, and people didn’t even have to bind it to their bodies using scars or spellwork.

Her best friend, Lark, woke up one morning with his palms prickling, the way skin did sometimes after it went numb, and you had to rub the feeling back. A few days later, he had a fever, sweat shining on his face, and it scared Kosika to see him so sick. She tried to swallow up the fear, but it made her stomach hurt, and all night she lay awake, convinced that he would die and she’d be even more alone. But then, the next day, there he was, looking fine. He ran toward her, pulled her into an alley, and held out his hands, cupped together like he had a secret inside. And when he opened his fingers, Kosika gasped.

There, floating in his palms, was a small blue flame.

And Lark wasn’t the only one. Over the last few months, the magic had sprouted up like weeds. Only it never really grew inside the grown-ups—at least, not in the ones who wanted it most. Maybe they’d spent too long trying to force magic to do what they wanted, and it was angry.

Kosika didn’t care if it skipped them, so long as it found her.

It hadn’t, not yet.

She told herself that was okay. It had only been a few months since the new king took the throne and brought the magic with him. But every day, she checked her body, hoping to find some hint of change, studied her hands and waited for a spark.

Now Kosika shoved the amplifiers in her pocket with the sugar cubes, and slid the secret drawer shut, and headed for the front door. Her hand was just reaching for the lock when the light caught on the wooden threshold and she jerked to a stop. It was spelled. She couldn’t read the marks, but Lark had taught her what to look for. She looked balefully back at the chimney—it was a lot harder going up than down. But that’s exactly what she did, climbing into the hearth, and shoving her boots back on, and shimmying up. By the time Kosika got back onto the roof, she was breathless, and soot-stained, and she popped another sugar cube into her mouth as a reward.

She crept to the edge of the roof and peered down, spotting Lark’s silver-blond head below, hand outstretched as he pretended to sell charms to anyone who passed, even though the charms were just stones painted with fake spells and he was really standing there to make sure no one came home while she was still inside.

Kosika whistled, and he looked up, head cocked in question. She made an X with her arms, the sign for a spell she couldn’t cross, and he jerked his head toward the corner, and she liked that they had a language that didn’t need words.

She went to the other side of the roof and lowered herself down the gutter, dropping to a crouch on the paving stones below. She straightened and looked around, but Lark wasn’t there. Kosika frowned, and started down the alley.

A pair of hands shot out and grabbed her, hauling her into the gap between houses. She thrashed, was about to bite one of the hands when it shoved her away.

“Kings, Kosika,” said Lark, shaking his fingers. “Are you a girl or a beast?”

“Whichever one I need to be,” she shot back. But he was smiling. Lark had a wonderful smile, the kind that took over his whole face and made you want to smile, too. He was eleven, gangly in that way boys got when they were growing, and even though his hair was as pale as the Sijlt before it thawed, his eyes were warm and dark, the color of wet earth.

He reached out and patted the soot off her clothes. “Find anything good?”

Kosika took out the amplifiers. He turned them over in his hands, and she knew he could read the spells, knew they were a good find by the way he studied them, nodding to himself.

She didn’t tell Lark about the sugar, and she felt a little bad about it, but she told herself he didn’t like sweet things, not as much as she did, and it was her reward for doing the hard work, the kind that got you caught. And if she’d learned anything from her mother, it was that you had to look out for yourself.

Her mother, who had always treated her like a burden, a small thief squatting in her house, eating her food and sleeping in her bed and stealing her heat. And for a long time, Kosika would have given anything to be noticed, to feel wanted, by someone else. But then children started waking up with fire in their hands, or wind beneath their feet, or water tipping toward them like they were downhill, and Kosika’s mother started noticing her, studying her, a hunger in her eyes. These days, she did her best to stay out of the way.

Lark pocketed the amulets—she knew whatever he got for them, he’d give her half, he always did. They were a team. He ruffled her in-between hair, and she pretended not to like the way it felt, the weight of his hand on her head. She didn’t have a big brother, but he made her feel like she did. And then he gave her a gentle push, and they broke apart, Lark toward wherever it was he went, and Kosika toward home.

She slowed as the house came into sight.

It was small and thin, like a book on a shelf, squeezed between two others on a road barely large enough for a cart, let alone a carriage. But there was a carriage parked in front, and a short man standing by the front door. The stranger wasn’t knocking, just standing there, smoking a taper, thin white smoke pluming around his head. His skin was covered in tattoos, the kind the grown-ups used to bind magic to them. He had even more than her mother. The marks ran over his hands and up his arms, disappearing under his shirt and reappearing at his throat. She wondered if that meant he was strong, or weak.

As if the man could feel her thinking, his head swiveled toward her, and Kosika darted back into the shadow of the nearest alley. She went around to the back of the house, climbed the crates beneath the window. She slid the frame up, even though it was stiff and she’d always had a fear that it would swing back down and cut her head right off as she was climbing through. But it didn’t, and she shimmied over the sill, and dropped to the floor, holding her breath.

She heard voices in the kitchen.

One was her mother’s, but she didn’t recognize the other. There was a sound, too. The clink clink clink of metal. Kosika crept down the hall, and peered around the doorway, and saw her mother and another man sitting at the table. Kosika’s mother looked like she always did—tired and thin, like a piece of dried fruit, all the softness sucked away.

But the man, she’d never seen before. He was stringy, like gristle, his hair tied back off his face. A black tattoo that looked like knots of rope traced the bones on his left hand, which hovered over a stack of coins.

He lifted a few and let them fall, one by one, back onto the stack. That was the sound she’d heard.

Clink clink clink.

Clink clink clink.

Clink clink clink.

“Kosika.”

She jumped, startled by her mother’s voice, and by the kindness in it.

“Come here,” said her mother, holding out her hand. Black brands ringed each of her fingers and circled her wrist, and Kosika resisted the urge to back away, because she didn’t want to make her mother mad. She took a cautious step forward, and her mother smiled, and Kosika should have known then, to stop out of reach, but she took another slow step toward the table.

“Don’t be rude,” snapped her mother, and there, at least, was the tone she knew. “Her magic hasn’t come in yet,” her mother added, addressing the man, “but it will. She’s a strong girl.”

Kosika smiled at that. Her mother didn’t often say nice things.

The man smiled, too. And then he jerked forward. Not with his whole body, just his tattooed hand. One second it was there on the coins and the next it was around her wrist, pulling her close. Kosika stumbled, but he didn’t let go. He twisted her palm up, exposing the underside of her forearm, and the blue veins at her wrist.

“Hmm,” he said. “Awfully pale.”

His voice was wrong, like rocks were stuck inside his throat, and his hand felt like a shackle, heavy and cold around her wrist. She tried to twist free, but his fingers only tightened.

“She does have some fight,” he said, and panic rose in Kosika, because her mother was just sitting there, watching. Only she wasn’t watching her. Her eyes were on the coins, and Kosika didn’t want to be there anymore. Because she knew who this man was.

Or at least, what he was.

Lark had warned her about men and women like him. Collectors who traded not in objects, but in people, anyone with a bit of magic in their veins.

Kosika wished she had magic, so she could light the man on fire, scare him away, make him let go. She didn’t have any power, but she did at least remember what Lark told her, about where to hit a man to make him hurt, so she wrenched backward with all her weight, forcing the stranger to his feet, and then she kicked him, hard, as hard as she could, right between his legs. The man made a sound like a bellows, all the air whooshing out, and the hand around her wrist let go as he crashed into the table, toppling the stack of coins as she shot toward the door.

Her mother tried to grab her as she passed, but her limbs were too slow, her body worn out from all those years of stealing magic, and Kosika was out the door before she remembered the other man, and the carriage. He came at her in a wreath of smoke, but she ducked beneath the circle of his arms, and took off down the narrow road.

Kosika didn’t know what they’d do if they caught her.

It didn’t matter.

She wouldn’t let them.

They were big but she was fast, and even if they knew the streets, she knew the alleys and the steps and all nine walls and the narrow gaps in the world—the ones that even Lark couldn’t fit through anymore. Her legs started to hurt and her lungs were burning, but Kosika kept running, cutting between market stalls and shops until the buildings staggered and the path climbed into steps and gave way onto the Silver Wood.

And even then, she didn’t stop.

None of the other children would go into the wood. They said it was dead, said it was haunted, said there were faces in the trees, eyes watching from the peeling grey bark. But Kosika wasn’t scared, or at least, not as scared of the dead forest as she was of those men, with their hungry eyes and shackle hands. She crossed the first line of trees, straight as bars on a cage, and kept going one row, two, three, before pressing herself back against a narrow trunk.

She closed her eyes, and held her breath, and tried to listen past the hammer of her heart. Listen for voices. Listen for footsteps. But the world was suddenly quiet, and all she heard was the murmur of wind through the mostly bare branches. The rustle of it on brittle leaves.

Slowly, she opened her eyes. A dozen wooden eyes stared back from the trees ahead. She waited for one of them to blink, but none of them did.

Kosika could have turned back then, but she didn’t. She’d crossed the edge of the woods, and it had made her bold. So she went deeper, walking until she couldn’t see the rooftops, or the streets, or the castle anymore, until it felt like she wasn’t in the city at all, but somewhere else. Somewhere calm. Somewhere quiet.

And then she saw him.

The man was sitting on the ground, his back against a tree, his legs out and his chin dropped against his chest, limp as a rag doll, but the sight of him still made her gasp, the sound loud as a snapping stick in the silent woods. She clapped a hand over her mouth and ducked behind the nearest tree, expecting the man’s head to jerk up, his hand to reach for a weapon. But he didn’t move. He must have been asleep.

Kosika chewed her lip.

She couldn’t leave—it wasn’t safe to go home, not yet—and she didn’t want to put her back to the man on the ground, in case he tried to surprise her, so she sank down against another tree, legs crossed, making sure she could see the sleeping stranger. She dug in her pockets, came up with the waxy bag of sugar.

She sucked on the cubes one at a time, eyes darting now and then to the man against the tree. She decided to save one of the sugar cubes for him, as thanks for keeping her company, but an hour passed, and the sun sank low enough to scrape the branches, and the air went from cool to cold, and the man still didn’t move.

She had a bad feeling, then.

“Os?” she called out, wincing as the sound of her voice broke the silence of the Silver Wood, the word bouncing off the hard trees.

Hello? Hello? Hello?

Kosika got to her feet and made her way toward the man. He didn’t look very old, but his hair was silver white, his clothes finely made, too nice to be sitting on the ground. He wore a silver half-cloak, and she knew, as soon as she got close enough, that he wasn’t sleeping.

He was dead.

Kosika had seen a dead body before, but it had been much different, limbs askew and insides spilled out onto the cobblestones. There was no blood on the man beneath the tree. He looked like he’d just gotten tired, and decided to sit down and rest, and never managed to get back up. One arm was draped in his lap. The other hung at his side. Kosika’s gaze followed it down to his hand where it touched the ground. There was something beneath his fingers.

She leaned closer, and saw that it was grass.

Not the hard, brittle blades that coated the rest of the Silver Wood, but soft, new shoots, small and green and spreading out beneath him like a cushion.

She ran her fingers over it, recoiling when her hand accidentally grazed his skin. The man was cold. Her eyes went to his half-cloak. It looked nice, and warm, and she thought of taking it, but she couldn’t bring herself to touch him again. And yet, she didn’t want to leave him, either. She took the last of the sugar cubes from the waxy bag and set it in his palm, just as a sound shattered the quiet.

The scrape of metal and the thud of boots.

Kosika leapt up, darting into the trees for cover. But they weren’t coming after her. She heard the steps slow, then stop, and she stopped, too, peering around a narrow trunk. From there, she couldn’t see the man on the ground, but she saw the soldiers standing over him. There were three of them, their silver armor glinting in the thin light. Royal guards.

Kosika couldn’t hear what they were saying, but she saw one kneel, heard another let out a ragged sob. A sound that splintered the woods, and made her wince, and turn her back, and run.

I

RED LONDON, now

Master Haskin had a knack for fixing broken things.

The sign on his shop door said as much.

ES HAL VIR, HIS HAL NASVIR, it declared in neat gold font.

Once broken, soon repaired.

Ostensibly, his business was devoted to the mending of clocks, locks, and household trinkets. Objects guided by simple magic, the minor cogs that turned in so many London homes. And of course, Master Haskin could fix a clock, but so could anyone with a decent ear and a basic understanding of the language of spells.

No, most of the patrons that came through the black door of Haskin’s shop brought stranger things. Items “salvaged” from ships at sea, or lifted from London streets, or claimed abroad. Objects that arrived damaged, or were broken in the course of acquisition, their spellwork having rattled loose, unraveled, or been ruined entirely.

People brought all manner of things to Haskin’s shop. And when they did, they invariably encountered his apprentice.

She was usually perched, cross-legged, on a rickety stool behind the counter, a tangle of brown curls piled like a hat on her head, the unruly mass bound up with twine, or netting, or whatever she could find in a pinch. She might have been thirteen, or twenty-three, depending on the light. She sat like a child and swore like a sailor, and dressed as if no one had ever taught her how. She had thin quick fingers that were always moving, and keen dark eyes that twitched over whatever broken thing lay gutted on the counter, and she talked as she worked, but only to the skeleton of the owl that sat nearby.

It had no feathers, no flesh, just bones held together by silver thread. She had named the bird Vares—prince—after Kell Maresh, to whom it bore little resemblance, save for its two stone eyes, one of which was blue, the other black, and the unsettling effect it had on those it met—the result of a spell that spurred it now and then to click its beak or cock its head, startling unsuspecting customers.

Sure enough, the woman currently waiting across the counter jumped.

“Oh,” she said, ruffling as if she had feathers of her own. “I didn’t know it was alive.”

“It’s not,” said the apprentice, “strictly speaking.” In truth, she often wondered where the line was. After all, the owl had only been spelled to mimic basic movements, but now and then she’d catch him picking at a wing where the feathers would be, or notice him staring out the window with those flat rock eyes, and she swore that he was thinking something of his own.

The apprentice returned her attention to the waiting woman. She fetched a glass jar from beneath the counter. It was roughly the size of her hand, and shaped like a lantern with six glass sides.

“Here you are then,” she said as she set it on the table.

The customer lifted the object carefully, brought it to her lips, and whispered something. As she did, the lantern lit, the glass sides frosting a milky white. The apprentice watched, and saw what the woman couldn’t—the filaments of light around the object rippled and smoothed, the spellwork flowing seamlessly as the woman brought it to her ear. The message whispered itself back, and the glass went clear again, the vessel empty.

The woman smiled. “Marvelous,” she said, bundling the mended secret-keeper away inside her coat. She set the coins down in a neat stack, one silver lish and four red lin.

“Give Master Haskin my thanks,” she added, already turning away.

“I will,” called the apprentice as the door swung shut.

She swept the coins from the counter, and hopped down from her stool, rolling her head on her shoulders to stretch.

There was no Master Haskin, of course.

Once or twice when the shop was new, she’d dragged an old man from the nearest tavern, paid him a lin or two to come and sit in the back with his head bent over a book, just so she could point him out to customers and say, “The master is busy working now,” since apparently a man half in his cups still inspired more faith than a sharp-eyed girl who looked even younger than her age, which was fifteen.

Then she got tired of spending the coin, so she propped a few boxes and a pillow behind a mottled glass door and pointed to that instead.

These days she didn’t bother, just flicked her fingers toward the back of the shop and said, “He’s busy.” It turned out, no one really cared, so long as the fixing got done.

Now, alone in the shop, the apprentice—whose name, not that anyone knew it, was Tesali—rubbed her eyes, cheekbones bruised from the blotters she wore all day, to focus her gaze. She took a long swig of black tea, bitter and over-steeped, just the way she liked it—and still hot, thanks to the mug, one of the first things she’d ever spelled.

The day was thinning out beyond the windows, and the lanterns around the shop began to glow, warming the room with a buttery light that glanced off the shelves and cases and worktops, all of them well stocked, but not cluttered, toeing the line between a welcome fullness and a mess.

It was a balance Tes had learned from her father.

Shops like this had to be careful—too clean, and it looked like you were lacking business. Too messy, and customers would take that business elsewhere. If everything they saw was broken, they’d think you were no good at fixing. If everything they saw was fixed, they’d wonder why no one had come to claim it.

Haskin’s shop—hershop—struck the perfect balance.

There were shelves with spools of cable—copper and silver, mostly, the best conduits for magic—and jars full of cogs and pencils and tacks, and piles of scrap paper covered in the scrawls of half-worked spells. All the things she guessed a repair shop might keep on hand. In truth, the cogs, the papers, the coils, they were all for show. A bit of set dressing to put the audience at ease. A little sleight of hand, to distract them from the truth.

Tes didn’t need any of these things to fix a bit of broken magic.

All she needed were her eyes.

Her eyes, which for some reason saw the world not just in shape and color, but in threads.

Everywhere she looked, she saw them.

A glowing ribbon curled in the water of her tea. A dozen more ran through the wood of her table. A hundred delicate lines wove through the bones of her pet owl. They twisted and coiled through the air around and above everyone and everything. Some were dull, and others bright. Some were single strands and others braided filaments, some drifted, feather light, and others rushed like a current. It was a dizzying maelstrom.

But Tes couldn’t just see the threads of power. She could touch them. Pluck a string as if it were an instrument and not the fabric of the world. Find the frayed ends of a fractured spell, trace the lines of broken magic and mend them.

She didn’t speak the language of spellwork, didn’t need to. She knew the language of magic itself. Knew it was a rare gift, and knew what people did to get their hands on rare things, which was exactly why she maintained the illusion of the shop.

Vares clicked his beak, and fluttered his featherless wings. She glanced at the little owl, and he stared back, then swiveled his head to the darkening streets beyond the glass.

“Not yet,” she said, finishing her tea. Better to wait a bit and see if any more business wandered in. A shop like Haskin’s had a different kind of client, once darkness fell.

Tes reached beneath the counter and pulled out a bundle of burlap, unfolding the cloth to reveal a sword, then took up the pair of blotters. They looked like spectacles, though the gift lay not in the lens, but in the frames, heavy and black, the edges extending to either side like the blinders on a horse. Which is exactly what they were, blotting out the rest of the room, narrowing her world to just the space of the counter, and the sword atop it.

She settled them over her eyes.

“See this?” She spoke to Vares, pointing to the steel. A spell had originally been etched into the flat side, but a portion of it had scraped away in a fight, reducing the blade from an unbreakable weapon to a scrap of flimsy metal. To Tes’s eyes, the filaments of magic around the weapon were similarly frayed.

“Spells are like bodies,” she explained. “They go stiff, and break down, either from wear or neglect. Reset a bone wrong, and you might have a limp. Put a spell back in the wrong way, and the whole thing might splinter, or shatter, or worse.”

Lessons she’d learned the hard way.

Tes flexed her fingers, and ran them through the air just over the steel.

“A spell exists in two places,” she continued. “On the metal, and in the magic.”

Another fixer would simply etch the spell into the blade again. But the metal would keep getting damaged. No, better to take the spell and weave it into the magic itself. That way, no matter what happened to the sigils on the steel, the power would hold.

Carefully, she reached into the web of magic and began to mend the threads, drawing the frayed ends together, tying tiny knots that then fell away, leaving the ribbons smooth, intact. She got so lost in the work, she didn’t hear the shop door open.

Didn’t notice, not until Vares perked up, beak clicking in alarm.

Tes looked up, her hands still buried in the spell.

With the blotters on, she couldn’t see more than a hand’s width, so it took her a moment to find the customer. He was large, with a hard face, and a nose that had been broken more than once, but her attention went, as it always did, to the magic around him. Or the lack of it. It wasn’t common to see a person without any power, and the utter absence of threads made him a dark spot in the room.

“Looking for Haskin,” he grunted, scanning the shop.

Tes carefully withdrew her fingers, and tugged the goggles off, flicking the burlap back over the sword. “He’s busy,” she said, tipping her head toward the rear of the shop, as if he were back there. “But I can help.”

The man gave her a look that made her hackles rise. She only got two kinds of looks: appraising, and skeptical. Those who saw her as a woman, and those who saw her as a girl. Both looks made her feel like a sack of grain being weighed, but she hated the latter more, that way it was meant to make her feel small. The fact, sometimes, it did.

The man’s hard eyes dropped to the sword, its hilt poking out from beneath the burlap. “You even old enough to handle magic?”

Tes forced herself to smile. With teeth. “Why don’t you show me what you have?”

He grunted, and reached into his coat pocket, withdrawing a leather cuff and setting it on the table. She knew exactly what it was, or rather, what it was meant to be. Would have known, even if she hadn’t glimpsed the black brand circling his left wrist as he set it down. That explained the lack of threads, the darkness in the air around him. He wasn’t magicless by nature—he’d been marked with a limiter, which meant the crown had seen fit to strip him of his power.

Tes took up the cuff, and turned it over in her hands.

Limiters were the highest price a criminal could pay, shy of execution, and many considered it a harsher punishment, to live without access to one’s magic. It was forbidden, of course, to bypass one. To negate the limiter’s spell. But forbidden didn’t mean impossible. Only expensive. The cuff, she guessed, had been sold to him as a negater. She wondered if he knew that he’d been ripped off, that the cuff was faulty, the spellwork unfinished, a clumsy snarl in the air. It was never designed to work.

But it could.

“Well?” he asked, impatient.

She held the cuff between them. “Tell me,” she said, “is this a clock, a lock, or a household trinket?”

The man frowned. “Kers? No, it’s a—”

“This shop,” she explained, “is licensed to repair clocks, locks, and household trinkets.”

He looked pointedly down at the sword sticking out of the burlap. “I was told—”

“It looks like a clock to me,” she cut in.

He stared at her. “But it’s not a clock . . . ?” His voice went up at the end, as if no longer certain. Tes sighed, and gave him a weighted look. It took far too long for him to catch it.

“Oh. Yes.” His eyes flicked down to the leather cuff, and then to the dead owl, which he’d just realized was watching him, before returning to the strange girl across the counter. “Well then, it’s a clock.”

“Excellent,” she said, pulling a box from beneath the counter and dropping the forbidden object inside.

“So he can fix it?”

“Of course,” Tes said with a cheerful grin. “Master Haskin can fix anything.” She tore off a small black ticket with the shop’s sigil and a number printed in gold. “It’ll be ready in a week.”

She watched the man go, muttering about clocks as the door swung shut behind him. She started to wonder what he’d done to earn that limiter, but caught herself. Curiosity was more danger than a curse. She didn’t survive by asking questions.

It was late enough now, the tide of foot traffic beyond the shop retreating as the residents of the shal turned their attention toward darker pursuits. It got a bad reputation, the shal, and sure, it could be a rough place. The taverns catered to those who’d rather not cross paths with the crown, half the coin used in the shops had come from someone else’s pocket, and residents turned their backs at the sound of a cry or a fight instead of running in to stop it. But people relied on Haskin’s shop to fix and fence and not ask questions, and everyone knew that she was his apprentice, so Tes felt safe—as safe as she could ever be.

She put away the unfinished sword, downed the last of her tea, and went about the business of locking up.

Halfway to the door, the headache started.

Tes knew it was only a matter of time before it made itself at home inside her skull, made it hard to see, to think, to do anything but sleep. The pain no longer took her by surprise, but that didn’t make it any less a thief. Stealing in behind her eyes. Ransacking everything.

“Avenoche, Haskin,” she murmured to the empty shop, fishing the day’s coin from the drawer with one hand and sweeping up Vares with the other, heading past the shelves and through the heavy curtain into the back. She’d made a nest there, a corner for a kitchen, a loft with a bed.

She kicked off her shoes, and put the money in a metal tin behind the stove before heating up a bowl of soup. As it warmed, she freed her hair from the pile on her head, but it didn’t come down so much as rise around her in a cloud of nut-brown curls. She shook her head and a pencil tumbled out onto the table. She didn’t remember sticking it there. Vares bent his skull to peck at the stick as she ate, soaking up broth with hunks of bread.

If anyone had seen her then, it would have been easy to guess that the apprentice was young. Her bony elbows and sharp knees folded up on the chair, the roundness of her face, the way she shoveled soup into her mouth and kept up a one-sided conversation with the dead owl, talking out how she’d finish the negater, until the headache sharpened and she sighed, and pressed her palms against her eyes, light ghosting on the inside of the lids. It was the only time Tes longed for home. For her mother’s cool hands on her brow, and the white noise of the tide, the salt air like a salve.

She pushed the want away with the empty bowl, and climbed the ladder up into the little loft, setting Vares on a makeshift shelf. She pulled the curtain, plunging the cubby into darkness—as close to dark as she could get, considering the glow of threads that hovered over her skin, and ran through the little owl, and the music box beside him. It was shaped like a cliff, small metal waves crashing up against shining rocks. She plucked a blue thread, setting the little box in motion. A soft whoosh filled the loft, the breathlike rhythm of the sea.

“Vas ir, Vares,” Tes whispered as she tied a thick cloth over her eyes, erasing the last of the light, and then curled up in the little bed at the back of Haskin’s shop, letting the sound of waves draw her down to sleep.

II

The merchant’s son sat in the Gilded Fish, pretending to read about pirates.

Pretending to read, because the light was too low, and even if it weren’t, he could hardly be expected to focus on the book in front of him—which he knew by heart—or the half-drunk pint of ale—which was too bitter and too thick—or anything but the waiting.

The truth was, the young man wasn’t sure who—orwhat—he was waiting for, only that he was supposed to sit and wait, and it would find him. It was an act of faith—not the first, and certainly not the last, that would be asked of him.

But the merchant’s son was ready.

A small satchel rested on the ground between his feet, hidden in the shadow of the table, and a black cap was pulled low on his brow. He’d chosen a table against the wall, and put his back to it. Every time the tavern door swung open, he looked up, careful not to be too obvious, to lift only his eyes and not his whole head, which he’d learned from a book.

The merchant’s son was short on experience, but he had been raised on a steady diet of books. Not histories, or spell guides, though his tutors made him read those, too. No, his true education had come from novels. Epic tales of rakes and rogues, nobles and thieves, but most of all, of heroes.

His favorite was The Legends of Olik, a saga about a penniless orphan who grows up to be the world’s greatest magician/sailor/spy. In the third book, he discovers he’s actually of ostra blood, and is welcomed into court, only to learn that the nobles are all rotten, worse than the scoundrels he faces at sea.

In the fourth book—which was the best one, in his opinion—the hero Olik meets Vera, a beautiful woman being held hostage on a pirate ship—or so he thinks, but then discovers she’s actually the captain, and the whole thing was a ruse to capture him and sell him to the highest bidder. He escapes, and after that, Vera becomes his greatest foe, but never quite his equal, because Olik is the hero.

The merchant’s son feasted on those stories, supped on the details, gorged himself on the mystery, the magic, and the danger. He read them until the ink had faded and the spines cracked, and the paper was foxed at the edges from being thumbed, or from being shoved into pockets hastily when his father came around to the docks to check his work.

His father, who didn’t—couldn’t—understand.

His father, who thought he was making a terrible mistake.

The tavern door swung open, and the merchant’s son tensed as a pair of men ambled in. But they didn’t look around, didn’t notice him, or the black cap he was told to wear. Still, he watched them cross the room to a table on the other side, watched them flag the barkeep, watched them settle in. He’d only been in London a few weeks, and everything still felt new, from the accents—which were sharper than he’d grown up with—to the gestures, to the clothes and the current fashion of wearing them in layers, so that each outfit could be peeled apart to reveal another, depending on the weather, or the company.

The merchant’s son searched their faces. He was a wind magician by birth but those were common. He had a second, more valuable skill: a keen eye for details, and with it, a knack for spotting lies. His father appreciated the talent because it came in handy when asking sailors about their inventory, how a crate was lost, why a purchase had fallen through, or vanished en route.

He didn’t know why or how he could so quickly parse a person’s features. The flickering tension between the eyes, the quick clench of teeth, the dozen tiny tugs and twitches that made up their expression. It was its own language. One that the merchant’s son had always been able to read.

He turned his attention back to the book on the table, tried to focus on the words he’d consumed a hundred times, but his mind slipped uselessly across the page.

His knee bounced beneath the table.

He shifted in his chair, and flinched, the skin at the base of his spine still raw from the brand that bound him to his chosen path. If he focused, he could feel the lines of it, the splayed fingers like spokes running out from the palm. That hand was a symbol of progress, of change, of—

Treason.

That was the word the merchant had shouted as he’d followed his son through the house.

“You only call it that,” the younger man countered, “because you do not understand.”

“Oh, I understand,” snapped the merchant, face flushing red. “I understand that my son is a child. I understand that Rhy Maresh was a brave prince, and now he is a valiant king. Seven years he’s ruled, and in that time, he has avoided a war with Vesk, opened new trade channels, channels that help us, and—”

“—and none of that changes the fact that the empire’s magic is failing.”

The merchant threw up his hands. “That is nothing but a rumor.”

“It’s not,” said the son, adjusting the satchel on his shoulder. He had already packed, because a ship to London was leaving that day, and he would be on it. “A new Antari hasn’t emerged since Kell Maresh, a quarter century ago. Fewer magicians are showing an affinity for multiple elements, and more are being born with none at all. My friend’s niece—”

“Oh, your friend’s niece—” sniped the merchant, but his son persisted.

“She’s seven now, born a month after your king was crowned. She has no power. Another friend has a cousin, born within the year. Another, a son.”

The merchant only shook his head. “There have always been those without—”

“Not this many, or this close together. It is a warning. A reckoning. Something is broken in the world. And it’s been broken for a while. There is a sickness spreading through Arnes. A rot at the heart of the empire. If we do not cut it out, we cannot heal. It is a small sacrifice to make for the greater good.”

“A small sacrifice? You want to kill the king!”

The merchant’s son flinched. “No, we’ll motivate the people, and build their voices loud enough, and if the king is so noble as he claims, then he will understand that if he truly wants what is best for his kingdom, he will step aside and—”

“If you believe this will end without blood, then you are a traitor and a fool.”

The merchant’s son turned to go, and for the first time, his father reached out and caught his arm. Held him there. “I should turn you in.”

Anger burned in his father’s eyes, and for a moment, the merchant’s son thought that he would resort to violence. Panic bloomed behind his ribs, but he held the older man’s gaze. “You must follow your heart,” he said. “Just as I follow mine.”

The father looked at his son as if he were a stranger. “Who put this idea into your head?”

“No one.”

But of course that wasn’t true.

After all, most ideas came from somewhere. Or someone.

This one had come from her.

She had hair so dark, it ate the light. That was the first thing the merchant’s son had noticed. Black as midnight, and skin the warm brown that came with life at sea. Eyes the same shade, and shot through with flecks of gold, though he wouldn’t be close enough to see them until later. He’d been on the docks counting inventory when she arrived, cut like a blade through the boredom of his day.

One moment he was holding a bolt of silver lace up to the sun, and the next, there she was, peering at him through the pattern, and soon they were turning through the bolts together, and then the cloth was forgotten and she was leading him up the ramp of her ship, and laughing, not a delicate wind-chime laugh like the girls his age put on, but something raw, and wild, and they climbed down into the warm, dark hold, and he was undoing the buttons of her shirt, and he must have seen it then, the brand, like a shadow on her ribs, as if a lover had grabbed her there, burned their hand into her skin, but it wasn’t until after, when they lay flushed and happy, that he brought his own palm and fingers to the mark and asked her what it was.

And in the darkened hold, she’d told him. About the movement that had started, how fast and strong it had grown. The Hand, she’d said, would take the weakness in the world and make it right.

“The Hand holds the weight that balances the scale,” she said, stroking his bare skin. “The Hand holds the blade that carves the path of change.”

He devoured her words, as if they belonged to a novel, but they didn’t. This was better. This was real. An adventure he could be a part of, a chance to be a hero.

He would have sailed away with her that night, but by the time he returned to the docks, the ship was gone. Not that it mattered, in the end. She hadn’t been Vera to his Olik but she was a catalyst, something to turn the hero toward his purpose.

“I know you do not understand,” he’d said to his father. “But the scales have fallen out of balance, and someone must set them right.”

The merchant was still gripping his son’s arm, searching his face for answers, even though he wasn’t ready to hear them.

“But why must it be you?”

Because, thought the merchant’s son.

Because he had lived twenty-two years, and had yet to do anything of consequence. Because he lay awake at night and longed for an adventure. Because he wanted a chance to matter, to make a difference in the world—and this was it.

But he knew he couldn’t say any of that, not to his father, so he simply met the merchant’s eye and said, “Because I can.”

The merchant pulled him closer, cupped his son’s face in shaking hands. This close, he could see that his father’s eyes were glassy with tears. Something in him slipped and faltered, then. Doubt began creeping in.

But then his father spoke.

“Then you are a fool, and you will die.”

The son staggered, as if struck. He read the lines of the merchant’s face, and knew the man believed the words were true. Knew, then, too, that he’d never be able to convince his father otherwise.

The woman’s voice drifted back to him, then, up from the darkened hold.

Some people cannot see the need for change until it’s done.

His nerves hardened, and so did his resolve.

“You’re wrong,” he said quietly. “And I will show you.”

With that, the merchant’s son pulled free of his father’s hands, and walked out. This time, no one stopped him.

That had been a month ago.

A month, so little time, and yet, so much had changed. He had the brand, and now, he had the mission.

The door to the Gilded Fish swung open, and a man strolled in. His gaze swept over the tables before landing on the merchant’s son.

He broke into a smile, as if they were old friends, and even if the look had been leveled at someone else, the merchant’s son would have known it was a lie.

“There you are,” called the stranger as he strolled over to the table. He had the gait of a sailor, the bearing of a guard. “Sorry I’m late.”

“That’s all right,” said the merchant’s son, even as a nervous energy rolled through him, half excitement and half fear. The other man carried no satchel, and weren’t there supposed to be two of them? But before he could say more, the stranger cut in.

“Come on, then,” he said cheerfully. “Boat’s already at the dock.”

He tucked the book in his back pocket and rose, dropped a coin on the table, and threw back the last of his ale, forgetting that the reason he’d left it to warm was because it was too bitter and too thick. It stuck now to the sides of his throat instead of going down. He tried not to cough. Failed. Forced a smile, one that the other man didn’t catch because he’d already turned toward the door.

As soon as they were outside, the other man’s good humor fell away. The smile bled from his face, leaving something stern and hollow in its wake.

It occurred to the merchant’s son, then, that he didn’t actually know the nature of their mission. He asked, assuming the other man would ignore him, or go out of his way to speak in code. He didn’t. “We’re going to liberate something from a ship.”

Liberate, he knew, was just another word for steal.

The merchant’s son had never stolen anything before, and the other man’s answer only bred more questions. What thing? Which ship? He opened his mouth to ask, but the words stuck like the ale in his throat as they passed a pair of royal guards. The merchant’s son tensed at the sight of them, even though he’d committed no crime, not yet, unless you counted the mark smuggled under his clothes.

Which they would.

Treason, echoed his father’s voice, in time with his own heart.

But then the other man raised a hand to the soldiers, as if he knew them, and they nodded back, and the merchant’s son wondered if they knew the truth, or if the rebellion was simply that good at hiding in plain sight.

The Gilded Fish sat less than a ship’s length from the start of the London docks, so it was a short trip, one that ended at a narrow, nameless boat. Light enough to be sailed by a single wind magician, like himself, a fleet-bottomed skiff, the kind used for brief, fast trips, where speed was of more worth than comfort.

He followed the man up onto a short ramp onto the deck. As their boots sounded on the wood, his heart pounded just as loud. The moment felt vital, charged with power and portent.

The merchant’s son smiled, and put his hands on his hips.

If he were a character in a book, this was how his story would start. Perhaps, one day, he’d even write it.

Behind them, someone cleared their throat, and he turned to find a second man, a wiry figure who didn’t even bother to feign recognition.

“Well,” said the newest man, gaze scraping over the merchant’s son. The latter waited for him to go on, and when he didn’t, he held out a hand, was about to introduce himself, but the word was still on his tongue when the first man shook his head. The second stepped forward, poked him in the chest, and said, “No names.”

The merchant’s son frowned. Olik always introduced himself. “What will we call each other?”

The other men shrugged, as if this weren’t a crucial detail.

“There are three of us,” said the one who’d collected him from the Gilded Fish.

“You can count that high, can’t you?” said the other dryly. “He’s the first. I’m the second. Guess that makes you the third.”

The merchant’s son frowned. But then, he reminded himself, numbers were often symbolic. In the stories he had read, things often came in threes, and when they did, the third was always the one that mattered. The same must be true of people.

And so, as the lines were soon thrown off, and the boat drifted in the crimson current, and turned, the royal palace looming in their wake, the merchant’s son—now the third man—smiled, because he knew, from the crown of his head to the bottoms of his boots, that he was about to be the hero of this story.

And he couldn’t wait.

III

Alucard Emery was used to turning heads.

He liked to think it was his dashing looks—the sun-kissed hair, the storm-blue eyes, the warm brown skin—or perhaps his impeccable taste—he’d always had a flair for well-trimmed clothes and the occasional gem, though the sapphire no longer winked above his brow. Then, of course, it might be his reputation. A noble by birth, a privateer by trade, once captain of the infamous Night Spire, reigning victor of the final Essen Tasch (they hadn’t held another tournament since Vesk used the last to assassinate the queen), survivor of the Tide, and consort to the king.

Each on its own would have made him interesting.

Together, they made him infamous.

And yet, that night, as he ambled through the Silken Thread, no heads turned, no gazes lingered. The pleasure garden smelled of burnt sugar and fresh lilies, a perfume that wafted through the halls and drifted up the stairs, curling like smoke around the guests. It was a stately establishment, close enough to the Isle that the river’s red light tinted the windows on the southern side, and named for the white ribbons the hosts wore around their wrists to mark them from the patrons. And like all upscale brothels, its tenants were skilled in the art of unnoticing. The hosts could be counted on for their discretion, and if any patrons knew him, as they surely did, they had the good taste not to stare, or worse, to make a sce—

“Alucard Emery!”

He flinched at the volume of the voice, the brazenness of being called by name, turned to find a young man ambling toward him, already well into his cups. A single blue thread curled through the air around the youth, though only Alucard could see it. He was dressed in fine silk, the collar open to reveal a trail of smooth, tan skin. His golden hair was rumpled, and his eyes were black. Not edge to edge, like Kell’s, but perfect drops of ink that pooled in the center of the white, and swallowed up the pupils, so he couldn’t tell if they were shrunk to pinpricks, or blown wide with pleasure.

Alucard searched his memory until it produced a name.