Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Old Street Publishing

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

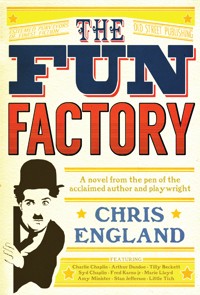

The Fun Factory is set in the golden decade before the Great War, when the music halls were the people's entertainment, before radio, television or cinema, and bigger than all of them. Arthur Dandoe is a gifted young comedian trying to make his way within the prestigious Fred Karno theatre company. Determined to thwart him at any cost is another ruthlessly ambitious performer - one Charlie Chaplin. Things turn even nastier when Arthur and Charlie both fall for the same girl, the irresistibly alluring Tilly Beckett. One of the two rivals is destined to become the most celebrated man on the planet, with more girls than he can shake his famous stick at. The other. . . well, you'll just have to read this book - his book. It could have been so different.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 625

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

EXPLANATORY NOTE

THE memoirs that make up this volume came into my hands quite unexpectedly one day. When my wife and I moved into the house in Streatham where we have now lived for nearly fifteen years we became friendly with the elderly lady who lived in the ground-floor flat of the large house next door, a Mrs Lander. One day we happened to be talking about my interest in comedy and comedians, and she said: “Of course, my grandfather knew Charlie Chaplin.”

“Really?” I said, thinking to myself: yes, and Lloyd George too, no doubt.

“Oh yes,” Mrs Lander said. “They were really quite thick, apparently.”

It seems incredible to me now, looking back, but I didn’t really pursue the subject. Eventually Mrs Lander moved to a residential care home, and then a few months later her daughter dropped round to tell us that sadly she had passed away.

“She wanted me to thank you for your kindness,” the daughter said, “and asked me to make sure you had this.”

The battered old trunk she left me – which was brown, reinforced by wooden ribs, and secured by what looked like an army belt – had been used as a repository for the memorabilia of a career treading the boards. There were wooden swords and shields, in the Roman style, and a lion skin (somewhat past its best). There was some old-fashioned football kit, a red shirt with a lace-up collar, long white pantaloons, and big boots that laced above the ankle. There was also a big black cape, of the sort you might see a magician wearing, and a top hat.

Underneath all this, lying flat at the bottom of the trunk, were papers, including posters from old music hall and vaudeville bills, mostly featuring the sketches of the great Fred Karno. Tucked in amongst these charming relics were old black-and-white photographs of groups of young men and women posing together, sometimes in theatrical costume and make-up, sometimes formally dressed, often in front of steam locomotives.

Who were they, I wondered, and what had they been doing?

I inspected the old photographs more closely. Surely that dapper young fellow with the toothy smile was Charlie Chaplin? And who was that one, standing over to one side, captured in an instant glowering at young Chaplin as though he would cheerfully throttle him till his eyes popped out?

Well, the answers were to be found in a brown leather satchel right at the bottom of the trunk, in the memoirs of the owner, one Arthur Dandoe, comedian.

I have no reason to doubt that they represent a truthful account, and where Dandoe touches upon verifiable historical fact he is invariably accurate – considerably more so than his contemporary managed in his 1964 autobiography, at any rate. Indeed, this memoir covers a period very swiftly – one might almost say, dismissively – dealt with in that other volume, and seems to have been written in response to it, in the spirit of setting the record straight.

Readers can judge whether or not Dandoe is to be believed regarding more personal matters. In editing the papers, I have confined myself, more or less, to the addition of a few historical notes.

C.W. England Streatham, May 2014

PART I

1

COLLEGE LIFE

“SO tell me – how did you get started?”

That’s what people always seem to want to know, as though finding out how mundane, how matter-of-fact, how accidental everything was at the kick-off will reassure them that it could all have happened to them, if only…

In point of fact the vast majority of theatrical performers I have met in my long and interesting life had the great advantage of being born into the game, never knowing anything else. Look no further than Chaplin’s autobiography. He paints a vivid, one might almost say melodramatic, picture of a childhood as the offspring of two music hall personalities. His father was a bona fide headliner, a baritone purveyor of faintly ribald singalong items who drank himself to death at the age of thirty-seven, and his mother was also a singer, who went by the name of Lily Harley. She lost her voice, and subsequently her marbles, and Charlie’s first exposure to the joys of being on stage came (he says) at five years of age. He had to stand in for her one night at the Canteen in Aldershot when she couldn’t face it, sang a song – “Jack Jones”, it was – scored a notable hit (of course, or it wouldn’t be in the book), and he was on his way.

I, on the other hand, unlike Charlie – and unlike Stan, whose father was a notable theatre impresario, and unlike Groucho and the boys, who were child performers with uncles and aunts in the vaudeville business – wasn’t born into it.

So how did I get started?

I take you back to Cambridge in the time of the old king, Edward VII, when the years, oddly (and evenly), began with “ought”. He was an enthusiastic visitor to the halls, by the way, old Bertie, used to come in disguise, but everyone recognised him, of course. His face was on the coins, after all.

So back in ought seven, it must have been, a glittering generation of carefree young things disported themselves about the old university town, sipping champagne in the sunshine on the banks of the Cam, flirting, carousing, occasionally dipping into a book or two, little dreaming that they were enjoying the last golden decade of the British Empire, and that the whole world order was just a few short years from changing for ever.

I was there too. Well, someone had to clean up after them, pick up their empties, make their beds, collect up their soiled laundry. And that someone was me. Arthur Dandoe, aged seventeen.

Not born into the theatre, you see. Born into servitude.

I’d lived in and around the college all my life. The school I went to until I was fourteen was just up the road. The little terraced house vouchsafed to the Dandoes by the college in its beneficence was about a hundred yards outside the main gate, up Trumpington Street.

All of my family belonged to the college, and had done going back into the mists of time. My mother, bless her, worked morning, noon and night in the kitchens, turning out exemplary breakfasts, luncheons and five-course suppers day after day. I wish I could say now that I miss my mother’s cooking, but the plain fact is I hardly ever got to taste any of it, certainly not during term time. Her best work was destined for a higher class of palate than mine.

Lance, my brother, six years older than me, had returned to college dogsbody status after a stint in the army. He had served in Southern Africa during the conflict there, and despite many attempts by me and the other lads to get him to tell us tales of derring-do and glamorous hand-to-hand fighting with the filthy pig-faced Boer, I only ever heard him use three words to describe his active service. These three words were: “I shit meself.”

And there was my father. He was the head porter, which gave him a certain amount of status about the place. No one, whether he was a plummy-voiced undergraduate, a crusty old brainbox, a college servant or – it has to be said – a family member, ever addressed him as anything other than “Mr Dandoe”. Woe betide the unthinking fool who popped his head into the porter’s lodge and said something like, “I say, porter chappy…?” or, worse, “I say, Dandoe, be a good chap and hail me a cab, there’s a good fellow…”

The back would straighten, the nose would crinkle, the thumbs would work their way into the waistcoat pockets, and my father would say: “I’ve lived and worked in this college for nigh on thirty year, man and boy. I’ve risen, in that time, to the position of head porter, like my father before me, and as such I believe I have earned the right to be addressed as ‘Mister Dandoe’.”

He would lurk in his little room in the porter’s lodge, which was built into the side of the original fourteenth-century archway at the main gate, like some gigantic spider. The invisible strands of his web stretched out to the furthest extremes of the college, and he was sensitive to its minutest vibrations. Nothing got past him.

All his hopes of the Dandoe line continuing its tenure of the porter’s lodge were vested in me, and I was a sad disappointment to him on this score. He seemed to have more or less given up on Lance, partly I think because when his eldest left to join the army all those years ago he put his king and country before the college, and to my father’s way of thinking that was simply the wrong way round.

“One day, lad,” he was fond of saying to me, if possible within earshot of Lance, “all this will be yours. You’ll be master of all you survey.”

Every time he’d say this I would grind my teeth a little bit more.

My father got it into his head, as part of his grand plan for me, that I should familiarise myself with all aspects of college servitude, and in this spirit he allocated me a staircase, O staircase, to be precise, and I began a period as a probationary bedder. Now, college bedders – or bedmakers to give them their full title – were invariably women, usually matronly figures chosen precisely because of the sheer unlikeliness that they would inflame the passions of the young gentlemen of the college. As you can imagine, I was not overly thrilled to count myself amongst their number.

I got my own back by perfecting a wicked impersonation of my father with which I’d entertain the other college servants behind his back. I got his voice off so pat that I could actually put the wind up folk if I spotted them slacking. On one occasion I came across two of the bedders sitting on the stairs having a good old chinwag when they should have been working. I tiptoed up to a spot one flight below them and just out of sight, and realised, gloriously, that they were having a right old go at my father and his ways. Picking my moment – just when one of them had ill-advisedly described the old man as “a tartar of the first order” – I bellowed at the top of my (or rather, his) voice: “So! That’s what you think of me, Clarice Thompson!”

I then climbed the stairs and peeked round the corner to find that Clarice was in gibbering hysterics and her companion, most gratifyingly, had fainted clean away.

Lance claimed outright that I could never fool him, though, so imagine my joy when our father caught him one Sunday having a sly smoke in the Wren chapel.

“Lancelot Dandoe! What in the name of all that’s holy do you think you are playing at?” he cried, outraged, to which Lance, without turning round to look, retorted: “Fuck off, Arthur, you little bastard. I know it’s you.”

“Oh! I…! Oh!” my father spluttered, incoherent with anger.

“Fuck off, I said, or I’ll kick your bony arse for you, you scrawny little shite…”

Lance was twenty-three, and had been in the army, remember, but he was still carted unceremoniously out of the chapel by the lughole, looking like nothing so much as my father’s pet orangutang.

On this one particular morning, the morning of the day when it all started, I’d helped out with breakfast, I had whizzed around the rooms on O staircase with the duster, and I’d popped back to the kitchens, where Mum was able to slip me a piece of cold bacon and a couple of slices of bread. I had a bolthole near the library, behind a big ugly black-green statue of William Pitt the Younger, a celebrated college old boy, and I tucked myself away there to get outside my bacon sandwich and read a ‘penny blood’. You’ll remember these, I’m sure – little flimsy storybooks packed with lurid adventures of pirates and cowboys, kidnapping and murder. (I forget how much they used to cost, now…)

My favourite tales were the ones set in America. Partly it was the grandeur of the place, the huge snow-capped mountain ranges, the mighty plunging canyons, the vast, sweeping desert plains. If you’d been born and brought up in Cambridge then you could get a kick out of almost any geographical feature grander than a slight incline. Mostly, though, it was the freedom it seemed to represent, the freedom to go where you wanted, be what you wanted, to rustle cattle or prospect for gold, to stake your claim for a piece of the New World.

So there I was, hidden behind a likeness of one of our great Prime Ministers, when suddenly a horny hand grabbed my collar and yanked me out. I spluttered, showering crumbs and half-chewed bacon over my father’s coat.

“There you are!” he cried. “I might have known you’d be skiving off somewhere. What about your staircase? What about your beds?”

“Fimmished…” I coughed. How did the old spider know I was there?

“Well, then why aren’t you laying out the luncheon in the Great Hall?”

“I was juft…”

“How on earth do you expect to ever get the lodge with this sort of attitude? Do you think your grandfather rose to become head porter of the college by lazing about the place? Do you think I gained that position in my turn by slacking off and backsliding?”

“Don’ wamp it…” I mumbled, still struggling with a mouthful of crusty bread. I don’t know where the nerve came from to answer back on this particular day. Ordinarily I’d have let the storm blow itself out.

“I beg your pardon!”

“Don’ wamp lodge. Don’ wamp be head porper…!”

My father had hold of the lapels of my jacket, and in his frustration he began to shake me, which didn’t help me to get rid of the mouthful of sandwich.

“Well … what do you want, then, tell me that? Tell me what glorious plan you have devised for yourself?”

I took a breath, a couple of furious chews, and swallowed. Then I looked up at my father, his exasperated face shining red.

“I … want to go to … America,” I said.

“America!” he scoffed, investing that one single word with every morsel of scorn he could muster. “I suppose we’ve got this trash to thank for that bright idea, have we?” He snatched the story from my hand and flicked through it contemptuously. “Well, young man, you can do the late rounds for me all this week. That’ll give you some time to think about the error of your ways.”

There was a curfew in operation at all the colleges and any student spotted on the streets after eleven at night by the ‘bulldogs’,1 could be fined the finicky but traditional sum of six shillings and eightpence – a third of a pound – and repeated infractions could result in a student being sent down, which meant sent home. Cambridge, you see, thought so much of itself that the only way was down once you left the place, even though geographically speaking it was so near to sea level that almost everywhere else was up.

The college, too, could levy a fine, called ‘gate pence’, to be paid to the porter, whose job it was to apprehend any bright spark trying to avoid stumping up this pittance by clambering in the back way. The well-oiled undergraduate would regard this as a kind of local sport and would think nothing of dumping you on your backside in an ornamental lily pond before shouting “Hullooo!!” and disappearing over the horizon. My father, understandably, had tired of this treatment over the years, and, as soon as I was big enough to take care of myself, doing the late rounds became his preferred punishment for me. Actually, I didn’t mind too much, as I soon realised that if I managed to catch anyone and get gate pence off them I could trouser it myself.

Later that evening, then, after the nobs had had their five-course dinners and their brandies and their ports, and everyone else had toddled off to bed, I was dawdling behind some bushes in New Court with a clear view of the single-storey bath house. I’d heard some rustling in the street outside as I passed the back gates, you see, and I suspected that someone was about to make an attempt.

Sure enough, after a moment or two I heard the telltale straining of some hero launching an assault on the north face of a lamp post, and then a leg was slung over the wall, followed by a backside, and finally a complete human form lay silhouetted against the lamplight playing on the building opposite.

To my astonishment, it was a woman. She was wearing a green frock, padded out by a number of petticoats, by the look of things, and she paused for a moment, panting in a most unladylike fashion from the exertion of the climb, before beginning to slide a shapely leg gingerly down the roof towards me.

I was delighted, because if some young rogue was trying to sneak a lady into his rooms then he was committing a serious sending-down offence and I should be able to extract a little more than just gate pence from him to keep his secret.

I watched for Romeo to make his appearance, but strangely there was no sign of him. Juliet, meanwhile, was leaning rather precariously over the guttering, and suddenly lost her grip, toppling headfirst into one of the large bins full of kitchen refuse. Well, I’m not sure what was in there that particular night, but nothing you’d want to be upside down in, that’s for sure. I broke cover and went to lend a hand. The lady had toppled the big bin over on its side by the time I reached her, and was truffling around in there looking for something. With an “Aha!” of triumph, she emerged, clutching her prize – covered in bits of potato peel and suchlike but still recognisably a rather fancy wig with lots of ringlets.

It was then that the penny dropped.

“Good evening, Mr Luscombe,” I said. Mr Luscombe was a first-year student, a friendly, cheerful chap whom I rather liked. (When I said earlier that his leg was shapely, you have to remember that it was quite dark, and the mind sees what it hopes to see, often, doesn’t it…?)

“Oh dash it all!” he moaned. “I hoped I was going to get away with this. Damnation!”

I assured him that his secret was safe with me, and he clutched my arm.

“I say, do you mean it? Stout fellow, stout fellow indeed…” He clambered to his feet and brushed kitchen rubbish from his frock, then looked around furtively.

“I’m afraid I’m going to have to trouble you for the late charge, though, Mr Luscombe, if you would be so kind.”

Luscombe’s hand went for his trouser pocket and then remembered that neither trouser nor pocket was there.

“Oh, hang it all! I say, listen, Dandoe, you’re a decent fellow, I know, and this must look dashed odd to you. How about you pop up to my rooms in a few minutes and I’ll see you right. And perhaps, what, a little bit extra, eh? What do you say?”

Well, Luscombe was all right in my book. Some of the other gentlemen of my acquaintance – including, I may say, Mr Luscombe’s humourless older brother, who had left the college to join the family business the previous summer – would lounge around pulling a face as though something had died on their top lips while I made their beds for them in the mornings. This Mr Luscombe, though, always had a smile and a cheery word or two, and so I nodded, and he darted off into the darkness like a startled rabbit.

I, meanwhile, carried on with the late rounds, ambling around the old courtyard and up to the Wren chapel, little realising that the course of my entire life had just been dramatically diverted.

2

THE SMOKING CONCERT

BY the time I got round to O staircase and tapped on his door, Luscombe had transformed himself back into the pink-faced young fellow that I knew, now wearing a mauve smoking jacket and dark trousers. A cigarette and a fire were on the go, and there was a small kettle dangling in his fireplace steaming away.

“Hallo, Dandoe, old chap,” he cried. “Come in, come in, let’s have a cup of tea, eh?”

I thought about offering to serve the tea up, but then thought, what the hell. If he wanted to play at being friends, then why not?

“You must be wondering what on earth I’ve been doing this evening?” he asked with a nervy laugh. I merely shrugged, as though I apprehended young gentlemen scrambling over the walls dressed as women every night of the week.

“Well, you’ll have heard of the Footlights Club?”

I hadn’t.

“Oh surely? The Footlights Club, no? The Honorary Degree? It was an absolute smash last summer, everyone was talking about it? Rottenburg wrote it. You must have heard of Rottenburg? Harry Rottenburg? The Rotter?”

I assured him that I knew of no Rottenburg. His face fell.

“Oh. Well, look here then. The Footlights Club is absolutely the premier dramatic society in Cambridge. Their shows are all comedy and music, none of this dreary highbrow stuff, The Taming of the Thing or The Merry Wives of Wherever, no, no, just the most tremendous fun. I’ve been simply desperate to join, and tonight after supper they were having auditions in a room in Magdalene. The Rotter’s speciality, as it happens, is female impersonation, and I’ve been getting together a little item for a smoker in college next week…”

I must have been looking blank, for he paused to fill me in.

“A smoker? A smoking concert. We have one every term in the Old Reader. Very informal, really. Chaps do a turn, or a song they’ve written, or a poem, or a dance. There’s a fellow called Hulbert2 in the first year at Caius, apparently he’s the most terrific clog dancer.”

Luscombe handed me a cup of tea.

“My turn, do you see, is going to be an address in the character of the Master’s Wife, Lady Marjorie. So I took the old costume along with me to the audition this evening, and do you know what those rotters at the Footlights did? They kept me waiting until the very last, and then finally while I was onstage, in character, doing the little monologue that I’ve worked out, they pinched all my own clothes and disappeared into the night.”

He wore such an expression of pop-eyed outrage that I had to laugh, and after a moment he began to giggle as well.

“I didn’t even notice they’d all gone right away. I thought I wasn’t getting many laughs. Really, those rotters! They’ve got my wallet and everything…”

Mention of his lost wallet reminded me that I was there to collect gate pence from him, and also the “little bit extra” that he had mentioned.

“It’s past midnight, Mr Luscombe,” I began. “I should be on my way, really…”

“Oh yes, yes, my dear fellow, I’ll see you right, of course…”

He pottered about looking for coppers on the dresser, but I could see that his mind was on something else, and suddenly he turned to me with a thoughtful expression on his face.

“I say, listen here, Dandoe. I wonder if you would like to help me out.”

“If I can, sir, of course,” I said, a little wary.

“Well, look, it’s about my turn, my monologue. You see, I want it to be a big surprise at the smoker when I come on as Lady Marjorie, and if word gets out it’ll ruin the moment. You see that?”

I supposed that made sense.

“So I was thinking, since you’ve already seen, I mean, the cat’s out of your particular bag, as it were, perhaps you wouldn’t mind having a quick look and letting me know what you think…?”

“I … er…”

“Stout fellow! It’ll only take a moment to pop the kit back on and I’ll be right with you!”

I tried to say there was no need to make this a dress rehearsal, but he’d already shot into his bedroom like a rabbit down a hole, and I could hear petticoats a-rustling. After a minute or two the bedroom door opened a few inches and Luscombe’s voice declaimed from within: “Gentlemen, would you give your best attention please to the Master’s wife, Lady Marjorie.”

Then the door was flung open and in he strode in the green dress and the wig once again.

“Good evening, my boys, and my what big boys you all are…!”

I knew pretty well what Lady Marjorie herself was like in real life, having served afternoon tea at the Master’s lodge. Mr Luscombe had the lady’s querulous tone off pretty well, and he certainly looked the part, and as I watched him recite his monologue a curious thing began to happen.

It was the first time I’d ever seen anyone trying to perform comedy. I’d never been to a pantomime or a circus, never even set foot inside a theatre, and yet as I was sitting there I felt my mind begin to whirr and click, little hammers hammered and tiny cogs ground their teeth together. It was an extraordinary sensation. I found myself assessing each line, each movement, each little aspect of the impersonation as it went by, mentally ticking off the bits that I thought would work and crossing out the bits that wouldn’t. Yes, that’s not bad, I was saying to myself, exaggerate that a little more, repeat that, lose that. I was really starting to enjoy myself, actually, and before I knew it he’d finished and was looking at me.

“You didn’t laugh,” he said, crestfallen.

“I’m sorry, sir,” I said.

“I thought ‘good for your blood’ would get you going, I really did.” He slumped forlornly into the easy chair opposite.

“Yes, now that’s a good line, but you should bring it in a lot more often.”

“More often, you say?” he frowned.

“I think so, yes.” I could see, suddenly, that he was feeling a little bit sensitive, and so I hesitated to say anything further, but he pressed me.

“And have you any more bright ideas, Mr Dandoe?”

I took a deep breath to get my thoughts in order. “Well, I think you would find it much easier if you were to sit down rather than standing. Most of your audience will know Lady Marjorie from having tea at the lodge – in fact why don’t we pretend that the whole performance is an afternoon tea at the lodge…”

A spark of interest ignited in my companion, and he leaned forward in his chair.

“Now you’re sitting like a man in a dress,” I said, emboldened. “Knees together, and perhaps to one side. Yes, that’s better, and back absolutely straight. That’s good. Now suppose we put a little table here with a cup and saucer on it, then … then, you can use Lady Marjorie’s little trick.”

“Whatever do you mean?”

I couldn’t believe I was the only one who’d noticed this. Lady Marjorie was a fearsome woman with a voice like a foghorn and a physique that made you believe she could knock down a horse with a single punch, but she liked to affect a feminine weakness, making out that lifting a cup and saucer full of tea was the most tremendous burden.

“Would you be so very kind?” she would simper, obliging some young chap to leap to his feet and hand her a cup which she could very easily have reached herself from a table only a couple of feet away. I was always sure that she did this with the sole intention of having young male consorts bending in front of her so that she could ogle their firm athletic backsides.

“Yes! Yes!” Luscombe shrieked, delighted. “The very thing! I’ve seen her do it a dozen times! Let me try…”

We quickly devised a little bit of business whereby his Lady Marjorie would require someone from the audience to lift the heavy cup and saucer for her, and then leer lewdly at his rear end for a moment, seen by the audience but not the unwitting stooge.

Lady Marjorie was utterly fanatical about rowing. “A boy should row,” she’d pontificate at the drop of a hat. “It’s good for the blood!” Luscombe had already used this line once in his routine, but I reckoned – I don’t know how, it was instinctive – that he needed to repeat it over and over again and its impact would build. Before long the script had developed to a point where tea was good for the blood, walking was good for the blood, parsnips were good for the blood, and looking at saucy French lithographs in the privacy of your own home was good for the blood.

Hours slipped by unmarked, consumed in gleeful invention, and as the dawn began to light the chimneys on the far side of the New Building our conversation had turned to other amusing college characters. I found myself demonstrating my own party piece: my impersonation of my father.

“That’s priceless, you know?” Luscombe gurgled between laughs. Both of us had become pretty hysterical by this time, and were laughing at almost anything.

“I’m serious,” he insisted. “You could do that at the smoker. You should do that at the smoker. It would be an absolute smash hit. I’ll speak to Browes, he’s organising the whole thing. Do it, say you’ll do it. It will be a sensation!”

Which is how I found myself a week later, still not quite believing it, in the Old Reader, about to make my theatrical debut. There was a little raised stage, with a pianist improvising some agreeable plinky-plonk while a noisy audience of a hundred and twenty souls paid no attention to him whatsoever.

I peered out through a gap in the hastily strung black curtain that formed the impromptu wing. The room was packed. A fug of smog hung down from the low ceiling, being fuelled by dozens of cigars like the chimneys of some great industrial metropolis. Champagne corks popped and young male voices brayed and hee-hawed boozily.

Standing there out of sight in my father’s clothes, a cushion padding out my tummy, my left leg trembling apprehensively of its own accord, the week just past seemed like a bizarre dream.

I remembered Mr Luscombe’s excitement as he told me that he had fixed it with Mr Browes, who was organising the smoker, for me to perform, and the churning of my guts as I realised there was no way to back out of it.

I remembered lying awake at night in the tiny room I shared with Lance, gripped with terror, and nudging my brother into the land of the living.

“Lance? You awake? I want to ask you something.”

He sighed, rolling over to face me, one eye open. “What?”

“When you were in Africa…?”

He groaned. “When I was in Africa? Lea’ me ’lone…”

“You were scared, weren’t you?”

“I told you, didn’t I?”

“Yes, but how did you …? How did you … manage, when you were really scared? How did you manage to carry on?”

“I tried to stay downwind of as many people as I could so that they didn’t know how scared I was.”

“Seriously, Lance.”

“Well, I’ll tell you this. It was always worse before than it was during.”

“Really?”

“Unless you were one of the blokes who got shot in the head or had an arm blown off. Then it was worse during. Now go sleep…”

“Lance, listen…”

I told him about the smoker, about what I’d somehow agreed to do, and he rolled over and looked at me, before saying: “There’s nothing to be scared of. How many of ’em are going to have repeating rifles? How many of ’em are going to try and chop you to bits with machetes?”

“Not too many, probably…”

“Exactly. Now go to sleep…”

There was a rustling, as of a big and complicated frock, and Mr Luscombe was beside me, also peering out.

“Decent crowd!” he hissed. On the other side of the curtain another cork popped, and half a dozen boisterous voices whaheyed as their owners thrust their glasses forward for a refill. Luscombe suddenly hiked up his skirt and retrieved a hip flask from his trouser pocket. “Here,” he winked, “bit of Dutch courage. Why not?”

I took a sip and felt the spirit trace the shape of my insides in fire.

“Why Dutch courage, I wonder, when it’s Scotch whisky?” Luscombe was musing to himself. “Do the Dutch even make whisky? And what do they have to be so damn timid about? Living next door to all those Germans, I suppose. Ha!”

Mr Browes, the tall, athletic young fellow who was in charge of the evening’s proceedings, pushed past us and pinned a sheet of paper to the wooden panelling, out of sight of the audience. Luscombe nudged me in the ribs.

“Running order,” he whispered, shouldering his way forward to get a view of it past about eight chaps in boaters and stripy blazers. “These fellows are first,” he said, “then me. Crikey, I was hoping not to be so early. You’re midway through, after the clog dancing.”

The fear gripped me once again. The fear of failure, of making a fool of myself, and in front of these people, who already held me in such low regard (if indeed they gave me a second thought).

Mr Browes completed a hurried headcount of the boaters-and-blazers, and then, satisfied, bounded past us and up onto the stage. The piano player tinkled to a little flourish of an ending and shut up, which is more than you could say for the packed and sozzled crowd.

“Gentlemen! Gentlemen, if you please!” Browes bellowed, and gradually heads began to turn in the direction of the little dais and the hubbub slowly subsided.

“Gentlemen,” Browes began, in a more conversational tone now he had their attention. “Thank you for patronising our little entertainment this evening. It is still not too late to participate if you feel so inclined. See me during the interval and if you have your sheet music, or if Edward knows the ditty you have in mind, then I’ll happily squeeze you into the second half.” There were one or two lewd haw-haws at this, though quite where the double-entendre they thought they had spotted was lurking was beyond me. “And now,” Browes went on, “let the revels commence!”

The first part of the evening went past in a blur. I think the opening item was a song by the chaps in boaters, accompanied by the pianist, a jolly little ditty about why you should always have champers in your hampers. There was a verse in it about all the different ways of popping your cork which they were inordinately proud of.

Then it was Mr Luscombe’s turn.

“Wish me luck!” he grinned, and then stepped out into the light. His Lady Marjorie started a touch uncertainly, it seemed to me, but once he got his first big laugh under his belt – actually, for the bit of business that we’d devised together in his rooms – his confidence grew. By the end he was getting uproarious laughter every time Lady Marjorie opined that something was “Good for the blood!”, and he left the stage to a thunder of applause.

Flushed and triumphant, he bustled into the wings and grasped me by the hand.

“My dear chap!” he whispered, “what tremendous fun! And I have you to thank, you know! Yes indeed!”

I was happy for him, and naturally pleased that my contribution had made a difference. Mostly, though, I was envious. He had finished.

The jovial mood that Luscombe’s performance had generated in the room gradually dissipated during the next few acts, which were not, it has to be said, the absolute apex. One, I remember, was a rather mournful poet delivering sorry odes on the theme of lost love. Fellows were not just yawning as he droned on, they were actually shouting the word “Yawn!”, but the drip didn’t take the hint.

Then there was the clog dancer. Everywhere you looked people were holding their ears and uttering oaths with absolute impunity. One or two were caught out by the suddenness of the cloggist’s finale and so he was greeted with a bellow of: “…ost confounded bloody racket I ever … oh, he’s stopped.”

Beside me in the wings Browes was frowning at his running order. The evening was spiralling helplessly down the drain, and we both knew it.

“Right-o,” he hissed as clog boy traipsed off with derision ringing in his ears (ours were just ringing). “You’re next…”

Browes hopped up onto the stage and held his hands up for quiet (ever the optimist).

“I am sorry to have to tell you, gentlemen, that the college authorities have informed me that your behaviour so far this evening has left something to be desired…”

A choral “Oooooh!” rose from the audience, half-pleased with themselves for the raucous good time they were having, half-outraged that anyone might dare to criticise them for having it.

“And … and … they have instructed me to make way for our esteemed head porter, Dandoe here, to speak to you for a few moments. Gentlemen, please…!”

There was a murmur, now, of sullen displeasure. I began to doubt the wisdom of the conceit I had devised, but it was too late now. Concentrating hard on holding back the trembling in my limbs, I walked out to the middle of the stage in a fair imitation of my father’s arthritically shuffling gait. The combined effect of that, the padding round my waist, the borrowed bowler hat and striped (second-best) waistcoat, and the cigar smoke blurring people’s vision meant, I’m sure, that most, if not all, of the assembled company, took me for the genuine article.

There was silence. Utter, horrible, silence. A second, two, three…

My brain suddenly emptied of all thought.

“Well, come on then!” came a voice from the back, cutting through the silence. “Get on with it, for goodness’ sake!”

The casual rudeness of it, the lack of respect that they felt towards me, or rather towards my father, snapped me back to myself. I wasn’t going to fail, not in front of these people.

“First of all,” I barked, “I’ve lived and worked in this college for nigh on thirty year, man and boy. I’ve risen, in that time, to the position of head porter, like my father before me, and as such I believe I have earned the right to be addressed as ‘Mister Dandoe’.”

Emboldened by anonymity, several of the audience ventured another “Woooh!” at this, which they’d never have done to the old man’s face, I’ll tell you that. I fixed them with a stern eye.

“Second, gentlemen. I have been sitting over in the porter’s lodge this past … half hour…” (taking out much-prized pocket watch and checking) “…and I’m exceeding sorry to have to report that the racket you are making in here this evening … well, I can hardly hear it. I’m very disappointed in you all.”

Bemusement mostly, as I looked around, but one or two titters beginning to ripple across the room.

“Ordinarily I look forward to your college smoking concerts, because the amount of disturbance you cause will usually bring the head porters of other colleges round to my lodge to complain, and otherwise I don’t get to see them much socially…”

By now they were starting to get it, and were beginning to laugh.

“Poor Dr Leather has a very important lecture to deliver tomorrow morning at the history faculty, and he was relying on you to keep him awake this evening long enough to finish copying what he was going to say out of Dr Simpson’s latest book. Well, I’m sorry to have to report that because of your half-heartedness a very distinguished academic career lies in ruins.”

Confidence building, I stuck my thumbs into my waistcoat pockets and strummed a little tum-tum-tiddle on my padded belly, as was my father’s wont when about to reminisce about previous generations.

“The smoker of Michaelmas term 1782, which I remember well, because it featured a young Arthur Wellesley doing the Wellington boot dance with which he later made his name, got such applause that plaster fell willy-nilly from ceilings as far away as Trumpington.”

Huge belly laughs, now, from everyone in the place. I could see gents turning to one another, asking who the devil I was, and some shrugs in response.

“If you gentlemen are unable to organise a smoking concert that draws complaints from at least as far away as St Catherine’s, I’m afraid we are going to have to forbid the use of the Old Reader until such time as you learn how to do one properly.”

The gauntlet thrown down, the ancient room reverberated to cheering, whistling, stamping, howling, a row like you’ve never heard before. I stood up there in front of the bedlam and had the curious sensation all of a sudden that something was missing. You know what it was? It was the fear.

In its place was something I have always since thought of as the power. Or rather: The Power.

Time seemed to slow down for me. I knew, I was absolutely certain, that everyone in the Old Reader at that moment was in my thrall. I held them in my hand. I didn’t know what I was going to say or do when they stopped cheering, but I did know that I would know, exactly. It was the finest feeling I’d ever had in my entire life.

As the laughter rolled around the room, I watched it, detached, serene, like a scientist watching an experiment going exactly according to plan. Through the haze of smoke I could make out individual faces, eyes fastened on me, mouths open in laughter or anticipation of laughter. And there, amongst the blazer-clad goons who had drifted round there after finishing their drippy song, I caught sight of a familiar face. Watching. Not laughing. Just watching.

My father.

3

OH! MR PORTER!

HE was looking directly at me. I was wearing his clothes, and his hat, and a parody of his paunch, and the better part of the population of the college, which was his whole world, was laughing at me. At him.

All this I spotted in the blink of an eye. I was able to register the sudden sight of him, digest it, consider its implications, set it aside for later, even as the laughter rolled on. The Power did this for me. I seemed to be operating at a different speed to the rest of the world, like the man in the H.G. Wells story whose trousers catch fire.3

And then it was over.

Browes was bounding out onto the stage again, leading applause for me, and I walked off slowly, carefully remaining in character, already wanting to do it again, and wondering how I was going to explain myself.

“Well done!” Mr Luscombe was saying. “Didn’t I tell you? You were a sensation…!”

Others clapped me on the back, wanting to share in my triumph. That clog-dancing fellow trod on my foot with his big wooden boot, but I hardly noticed. What was I going to say to my father? I should have known – nothing got past the old spider.

I slipped out through the library and out of the side door into the cool night air, leaving another group of bright young things to warble on about punting to Grantchester, or some such, and I stood with my back against the ancient stonework for a moment to gather my thoughts. Lance lurched around the corner and immediately spotted me.

“Now then, Arthur, before you say anything. I never let on,” he said, as he trotted over, his hands raised defensively in front of himself.

“Of course not,” I sighed.

“I never, I swear!” he protested, detecting the sarcasm in my voice. “He heard the rumpus and came over to see for himself what was going on!”

It had the ghastly ring of truth about it, I had to admit. That I should be onstage pretending to be my father berating the audience for not making enough noise, thus inspiring them to make more noise, and that that noise should then have been what brought him over to see what was happening, well, it was one of those naturally occurring moments of perfect comic irony that you can’t make up. I grunted, letting the lump off the hook.

“He wants to see you,” Lance said, grimacing in an unusual moment of fraternal sympathy. I shrugged and set off over to the lodge, the condemned man, to take my punishment (without hearty breakfast).

I shoved open the heavy old door slowly, setting the ancient hinges squealing. For once, though, my father wasn’t standing at the ready behind the counter, alerted by his early warning system.

“Hello…?”

His voice came from the back. “Come through.”

I nipped behind the counter and into his little back room, which was as snug and warm as a toasted muffin. There was a fire going in the grate and my father was sitting in his old comfy chair (his father’s before him). He waved me over to a stool opposite and I sat there with my hands on my knees for long agonising moments, waiting for the thunderstorm to strike.

“I was wondering where my second-best waistcoat had got to.”

“Sorry,” I said.

He looked me up and down as though seeing me for the first time. I didn’t know what to do to break the tension, so I took his bowler hat from my head and handed it over to him. He nodded, took it from me and set it on the small table at his side.

“Would you like me to do the late rounds tonight?” I said finally, unable to stand it any longer.

“I would appreciate that, Arthur, thank you.”

More oddly appraising silence followed, and then I ventured: “I’m sorry, if seeing what I did this evening was … embarrassing for you. I didn’t mean…” My sentence tailed off and he completed it for me: “…for me to see you at it, I know, I know. Well, I’ve got two things to say to you, Arthur Dandoe, and I sincerely hope you’ll pay attention to them.”

Here it comes, I thought, bracing myself.

“When I saw you up on the stage there tonight, well, I don’t mind telling you I got the shock of my life, I did. I saw you up there, dressed like me, speaking my words in my voice and heard all the gentlemen in there laughing and cheering, and do you know what I thought to myself? Do you?”

He wasn’t raising his voice. In fact he was frighteningly calm, and I’ll tell you what I was thinking to myself. I was thinking, this is the angriest I’ve ever, ever seen him. Even more angry than when Lance left and joined the army without telling anyone.

“Um … no…?”

“I thought to myself, well, Dandoe. Here’s a nice thing. Look at them all, laughing at you, laughing at your funny little ways. What does this all mean, I wonder…?”

He looked me right in the eye.

“I’ll tell you what it means, my lad. It means they like me. They really like me.”

Eh?

“Oh yes. It means I, George Dandoe, am more than just a college employee, the senior college employee. I’m beyond that now, oh yes, way beyond. I’m a college institution.”

He beamed.

“And do you know what else I thought?” he went on. “I thought to myself: look there, Dandoe, there’s your son. He’s had none of what all these other men have had, none of the privileges, none of the advantages, and look at him. He’s as good as every last one of them. Better even. They’re hanging on every word he says.”

I was stunned. Staggered.

“Good luck to you, son. You showed ’em, eh? Oh yes! You showed ’em all! Well done! I’m proud of you. I mean it.”

He leaned over, took my hand and pumped it enthusiastically, a warm smile spreading across his face.

“Now come on, look lively. Off with that waistcoat, and whatever else you’ve stuffed under there, you cheeky beggar…” – here he patted his tummy, more jovial than I’d ever seen him – “and then round to the Old Reader. Some of those gentlemen will need sending on their way if they’re not to be locked out of their own colleges…”

A couple of minutes later I was outside in the night air once again, shaking my head at my father’s reaction. I’d lampooned him in front of everyone, and he’d loved it! Well, you could have taken the proverbial feather and rendered me more or less horizontal with it.

The smoking concert was over by the time I reached the Old Reader, and it had dissolved into a loud and raucous drinking party. If anything, there was even more smoke than before, and you could see it swirling and drifting by the gas jets on the wall.

“Excuse me? Gentlemen? Could I have your attention?” I bellowed at the top of my voice. “The front gate will be closing in ten minutes. Those of you from other colleges should be on your way now.”

It was as if I was invisible. The Power clearly did not extend to the delivery of mere factual information. I gave up on them – after all, if they wanted to risk the wrath of the proctors’ bulldogs it was no business of mine. I stepped off the chair and took down one of the long poles to open the top windows, thinking to let out some of the smoke. I was reaching up to the first window, when Mr Luscombe rushed over and grabbed my arm.

“For goodness’ sake, put that down!” he hissed.

“I was just letting in some air,” I protested, but he was already hustling me briskly through the crowd.

“I know, I know, but there’s someone I want you to meet, and it would be better if he didn’t know you really were a porter. You see the fellow in the striped blazer?”

I did.

“Well, that’s the Rotter!”

“The rotter?”

“From the Footlights Club.”

“You mean the one who stole your trousers?”

“Exactly so.”

I drew myself up to my full height. “I see, sir. What do you want me to do? Do you want me to sling him out of the gates on his backside…?”

“No, no, no, no, no-o-o-o!” Luscombe urgently grabbed my arm again to hold me back. “He was in tonight, he saw the smoker and wants to talk to you, to me, to us! Come on!”

Harry Rottenburg – ‘The Rotter’ – was the president of the Footlights Club and – although I didn’t know it at that moment – he was the university’s leading theatrical celebrity. He was holding court at the far side of the room, surrounded by a dozen or more acolytes gazing at him worshipfully over the rims of their champagne glasses. The Rotter was somewhat older than his courtiers, having been a student himself some ten years earlier, and he now was a senior member of the university’s engineering department. His nickname was rather misleading, as “rotting”, or being a “rotter”, was undergraduate slang at that time for joking or sending someone up. Luscombe dragged me over and we hovered at his elbow, waiting for him to draw breath, which he did presently.

“Mr Luscombe, there you are. I congratulate you, sir. An excellent turn.”

Luscombe beamed. Praise from the Rotter was praise indeed. The Rotter was a burly figure, with broad shoulders and a square face that looked like it had been knocked about a bit. If his speciality, onstage that is, was playing female roles, then they must have been exclusively female characters who had played rugby union for Scotland (as he himself had).

“And I apologise for the high jinks with your clothing last time we met. I sent a man round to your rooms with the items. I trust they arrived safely?”

“Oh yes, thank you,” gushed Luscombe. “And there’s no need for apologies, really. Excellent rotting!”

“Well, there we are. And this is your man, is it?”

“Dandoe,” Luscombe put in, before I could speak for myself. “This is Dandoe, yes. Excellent chap.”

“I congratulate you too, Mr Dandoe, most entertaining.” The Rotter offered his hand and I took it. A huge, meaty fist it was too. “Here’s the gist,” he went on. “I’m putting together a show at the New Theatre. It’s practically written, and I dare say we’ll be able to find something for the two of you. What do you say?”

I was dumbstruck. Luscombe looked as though he had died and gone to heaven.

“I’d be deligh … that is to say, we’d be delighted, wouldn’t we, Dandoe? Yes indeed we would,” Luscombe jabbered, and before I could say a word on my own account it was all arranged, and the Rotter swept grandly out of the Old Reader with his retinue in his wake. Luscombe was quite beside himself with glee.

“Did you hear? We are to be in a Footlights show! How absolutely bally splendid!”

I was sorry to bring him down to earth, because surely it was impossible for me, a mere college servant, to take part.

“Ah, no, because I told Browes to tell the Rotter you were my manservant, my gentleman’s gentleman, do you see, and they would have no problem with that, it would be perfectly fine. It was all I could think of at the time, it was all rather sprung on me, and I wasn’t sure whether he liked you or me. But if you’re my man, do you see, he can’t have one of us without the other, so it fits the bill rather splendidly, doesn’t it?”

Well, whether it did or it didn’t, I’d felt the intoxicating thrill of the Power. I wanted more, and whatever it took I was going to make it happen.

4

THE VARSITY B.C.

IN the event, rather than try to pull the wool over my father’s eyes, I decided to come clean right away – well, the next day – and tell him about the conversation with the Rotter. Remarkably, it turned out that he was quite happy to accommodate my absence in the evenings, as long as I was prepared to make up the hours late at night – more late rounds – and early in the mornings. The crucial factor, I think, was that Mr Luscombe had decided to describe me as his gentleman’s gentleman. There were few ways in which a college servant could hope to improve himself, other than graduating to head porter, but being taken into private service by a wealthy gentleman when he left the college was certainly one of them.

And so, shortly thereafter, Mr Luscombe and I found ourselves taking part in Mister Harry Rottenburg’s newest venture, a production called The Varsity B.C.

There was a busy hum about the university at that time. You couldn’t miss it, even if you were only serving the port at High Table. The chatter was all about dinosaurs, and fossil bones which somehow proved that giant lizards had once ruled the earth. Back then, in ought seven, these bones were being discovered all the time.

Some of the finest minds in Cambridge were absorbed in the business of connecting these prehistoric monsters with animals that still lived on the planet, hoping to shed light on some of the murkier corners of the theory of evolution. Others, like the Rotter, were thinking along different lines, such as: “I say, wouldn’t it be an absolutely spiffing lark to make a model of a brontosaurus and have it eat a chap?”

So while on one side of town the archaeologists and anthropologists pored over ancient ribs and bits of spine, on the other the engineering department were devising a complicated system of wires and pulleys, weights and counterweights that would allow the Rotter to climax his new show with a full-size moving brontosaurus – its head and neck, at any rate – with room in its mouth for a human snack.

And who do you think was in line to be lizard lunch? That’s right, yours truly.

The conceit of the show, as you can probably guess from the title, was to depict Cambridge in prehistoric times. Rival groups of cavemen from rival caves would compete in a variety of activities which aped – rotted, I should say – college life, with the whole scheme enlivened by the appearance of the mechanical dinosaur.

Mr Luscombe and I had relatively small parts to play, as cavemen from ‘St Botolph’s cave’. I was Caveman 4, and I’m pretty sure that Luscombe was Caveman 3. There was a deal of standing around in animal skins, and numerous scenes in which twenty or more of us were running around trying to bop one another on the head with papier-mâché clubs. Caveman 4’s moment in the sun came near the end. It turned out, wouldn’t you know it, that I had been secretly working to further the interests of the Trinity cave, and I got my comeuppance when I was devoured by the brontosaurus.