Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Allen & Unwin

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

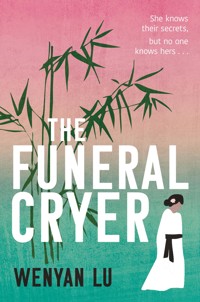

***'A refreshing perspective on mourning, as well as a moving tale of a social outcast' - i-D Magazine*** ***'Subtle and understated [...] ultimately very moving' - The Big Issue*** ***A fascinating glimpse into how [rural women's] lives are still led' - Dorset Magazine*** Is it ever too late to change your life? Elegant, wry and moving, The Funeral Cryer tells the tale of one woman's mid-life re-awakening in contemporary rural China and proves that it's never too late to alter your fate. The Funeral Cryer long ago accepted the mundane realities of her life: avoided by fellow villagers because of the stigma attached to her job as a professional mourner and under-appreciated by The Husband, whose fecklessness has pushed the couple close to the brink of break-up. But just when things couldn't be bleaker, The Funeral Cryer takes a leap of faith - and in so doing things start to take a surprising turn for the better . . . Dark, moving and wry, The Funeral Cryer is both an illuminating depiction of a 'left behind' society - and proof that it's never too late to change your life. What readers have been saying about The Funeral Cryer: 'A beautiful, thought-provoking book [...] incredibly humorous' - J. Wells, Five-star Reader Review 'A stunning debut' - Stacey, Five-star Reader Review 'A first person narrative that shows how the life of a middle-aged woman working as a funeral cryer in China is deeply linked to the people who touch her life and the way they treat her.' - Kate Poels, Five-star Reader Review 'A remarkable novel that explores themes of marriage, family relationships, elderly care, and gender equality [...] this book offers a unique reading experience and an opportunity for deep contemplation.' - Rui, Five-star Reader Review 'Excellent literary fiction. [...] Simultaneously the story speaks to the rural economic desperation, the separation of town and country, they way the young move to the cities and are often left with no other option to finance themselves than selling themselves. The huge discrepancy between the haves and have-nots is very evident.' - Cheryl M-M, Five-star Reader Review

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 432

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

‘Oscillating between tragedy and comedy, Wenyan’s novel is a refreshing perspective on mourning, as well as a moving tale of a social outcast.' i-D

'A fascinating glimpse into how [rural women’s] lives are still led.' Dorset Magazine

‘A captivating tale [...] China-born Lu adeptly weaves the ageold themes of filial piety and loyalty into the fabric of the story, highlighting the clash between tradition and modernity in her remote village setting.’Strait Times

'Full of poetry and longing.' Kirkus

‘Enlightening [...] a moving story, which sheds light on what life is like in modern rural China, the mixing of modern and traditional customs, and the bonds of love, responsibility and loyalty that underpin everyday lives.' NZ Booklovers

‘The prose is elegant and restrained, yet still manages to convey the protagonist’s anger that simmers between the pages like a dormant volcano. Highly recommend this stunning debut.’ Stacey Thomas, author of The Revels

‘Wonderful. A deft, humorous exploration of female desire and a forgotten society with a protagonist to love and root for.’ Irenosen Okojie, author of Butterfly Fish

‘This thought-provoking story will stay with me a long time [...] spectacular.’ Diane Billas, author of Does Love Always Win?

‘A fascinating insight into domestic rural life in China today. […] Her questions about her own life echo wider concerns about the persistence of traditional culture in modern China, as she negotiates being a good mother, a good daughter and a good wife in a bad marriage.’ Sarah Burton, author of The Strange Adventures of H

‘An exquisite, wholesome and insightful read about a China which many of us might never otherwise have a chance to visit.’ Chikodili Emelumadu, author of Dazzling

‘A fascinating exploration of another culture. The eponymous character shows us about life in rural China with a unique voice that can be both wry and heartbreaking. Through her interactions with the other villagers we get a glimpse of what life is like away from the big city.’ M. J. Hollows, author of The German Messenger

‘In haunting, elegiac prose, Wenyan Lu paints a world and profession that few of us are aware of in contemporary, rural China. How a professional mourner, a manipulator of emotions, wrestles with her own midlife crisis is at turns both tragic and comic, and has wide resonance beyond its rural setting.’ Yvonne Singh, Judge SI Leeds 2020

‘A wonderful story; so moving. A beautifully written, memorable novel.’ Kadija George

Originally from Shanghai, China, Wenyan Lu is the winner of the SI Leeds Literary Prize 2020. Wenyan holds a Master of Studies in Creative Writing as well as a Postgraduate Certificate in Teaching Creative Writing from the University of Cambridge. Her unpublished historical novel The Martyr's Hymn was also longlisted for SI Leeds Literary Prize 2018 and Bridport First Novel Prize 2019.

First published in hardback and trade paperback in Great Britainin 2023 by Allen & Unwin, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This paperback edition published in Great Britain in 2024 by Allen & Unwin.

Copyright © Wenyan Lu, 2023

The moral right of Wenyan Lu to be identified as the author of thiswork has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright,Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is availablefrom the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 978 1 83895 758 2

E-book ISBN: 978 1 83895 757 5

Printed in Great Britain

Allen & Unwin, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House, 26–27 Boswell Street

London WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For my mum and dad,who always think I am the best

Chapter One

Great-Great-Grandma was dead.

The whole village was touched by an eerie atmosphere, almost a strange relief. It seemed everyone had been secretly waiting for this moment to come.

She was Great-Great-Grandma to everyone in the village. I didn’t know how old she was at the time; we just knew she was alive. I felt a moment of surreptitious excitement and a shameful buzz in my chest since I would earn some money from her epic death.

A young woman in a white linen gown and a matching cloth hood approached me in the cramped kitchen. Walking on the street like this would be enough to reduce little children to tears.

She read Great-Great-Grandma’s obituary to me while I dabbed powder on my cheeks. Several village chefs and their helpers were preparing food amid much shouting and chopping. I could hardly move. I was surrounded by stacks of large cardboard boxes with ‘FRAGILE: PORCELAIN’ printed on them in thick black letters.

The young woman didn’t look happy, but she didn’t seem too sad either. Then again, I could be wrong. What you saw was not always what was there.

‘Will you really be able to remember her obituary?’ she asked me.

‘Yes.’

‘I’m just worried. If you make any mistakes, my uncle will be mad at me.’

‘You don’t need to worry. I promise everyone will cry. Trust me.’

‘Let me read it once again. Just to make sure,’ she said. I nodded and she began.

‘Dear Great-Great-Grandma lived an extraordinary life of 106 years. She selflessly devoted herself to the continuity and prosperity of her family. She suffered various hardships during her exceptionally long and enduring life and she did many remarkable things. She had twenty-five grandchildren, sixty-two great-grandchildren and sixteen great-great-grandchildren. More than thirty of her descendants live abroad. She will be remembered dearly by her family and her village. She lived the longest on record in our county, so we all feel tremendously proud of her. Her heartbreak was that seven of her grandchildren predeceased her. Let us cry for her and keep hope in our hearts for ourselves.’

I took a brief look at myself in the mirror. My face was pale, my eyebrows were painted long and my lips bright red: the perfect image for a traditional funeral cryer. There were several black and red make-up stains on my white gown, but nobody would notice them in their distress. The young woman had helped me to tie the big black cotton bow on the side of my gown. My bun was neat. I tugged some strands of loose hair along my temples and ears to cover my wrinkles. Finally, I pinned a white fabric flower carefully onto my hair.

The young woman handed me a small tea cup. ‘Your hair looks nice,’ she commented.

‘We’ve got a good barber in the village.’ I felt my bun.

‘Your belt is nice. Look at mine.’ Hers was a linen rope, a symbol of bereavement.

‘It doesn’t matter what it looks like. You have to wear it.’

‘You’re right. By the way, you need to eat something. Some rice biscuits?’

‘Thank you. I’ll keep some for the husband. He likes them.’

‘I’ll ask them to pack a box for you. Now, shall we rehearse a bit more? It’s not easy to get all those numbers right.’

‘Twenty-five grandchildren, but seven dead, sixty-two great-grandchildren and sixteen great-great-grandchildren.’

‘And don’t forget: she lived for 106 years.’

The courtyard was spacious but neglected, with weeds growing in the gaps between the chipped stone slabs. The guests were mostly sitting on small stools and benches. Some people were chatting, some were staring at their phones, and some were cracking sunflower seeds between their teeth. There was no sorrow or grief in the air just yet. Most people’s expressions were indifferent. When a relative or friend has lived so long, after their death there is often a sense of detachment amongst the funeral goers.

A suona sounded: the musical instrument of choice for countryside funerals in Northeast China, similar to a trumpet. High-pitched, squeaky and very noisy, like a wolf howling in a gale. It stopped after a minute or so. A tape of slow, heavy music began to play. The crowd fell silent as the coffin was carried into the courtyard from the back gate. It was a redwood coffin with patterns carved onto the lid, wrapped in white silk ribbons.

I watched as the pallbearers slowly lowered the coffin onto a makeshift stage, in the middle of a display of wreaths and baskets of flowers. The stage was a sea of colour.

As soon as the music faded and the pallbearers had retreated, I skipped up onto the stage waving my wide, flared sleeves high in the air. I knelt down in front of the coffin. This was my favourite part of the funeral crying. I felt like a beautiful actress on the stage.

All was silent.

I threw myself onto the ground and began to wail.

‘Oh, Great-Great-Grandma, have you really left us? Have you? The sky is murky and the earth is dark because of your absence. How can you bear to leave us behind? You had a turbulent life in the old society when you were young, but you never complained. In our new socialist society, you recovered from adversity thanks to the party, and you followed Chairman Mao’s appeal to produce as many children as possible for our motherland, seven altogether. Although you were not granted the official title of Heroic Mother by Chairman Mao, what you achieved in increasing the population of New China was glorious. You are survived by two daughters, eighteen grandchildren, sixty-two great-grandchildren and sixteen great-great-grandchildren. Such a feat. Who could ever wish for more in this life?’

I paused. No one was crying.

I took a deep breath, leaned forward and slapped the floor with both palms.

I repeated, ‘Oh, Great-Great-Grandma, have you really left us? Have you? The sky is murky and the earth is dark because of your absence. How can you bear to leave us behind? How?’

I rubbed my eyes. ‘Great-Great-Grandma, are you looking down at us from Heaven? Do you know how much we miss you? How bereft we are? We will remember you dearly. We will remember everything you did for your family and for your country. We are glad you are reunited with Great-Great-Grandpa in Heaven now. We couldn’t bear to think of you being alone.’

Some of the mourners started to rub their eyes. I slowed down.

‘Great-Great-Grandma, we hope you can see our tears.’

Nearly everyone was crying by now, and I felt pleased and relieved. I deserved the money I was going to be paid.

‘But life must go on. Great-Great-Grandma would now like to see us smile. We can’t be happy for a long, long time, and she knows that. It is true we are mourning her farewell, but we are also celebrating her rare longevity. She brought prosperity and pride to her relatives and to our village. Her family has arranged a banquet to show her the highest respect. We can share stories of our beloved Great-Great-Grandma. By the way, don’t forget to collect your longevity china bowl before you begin eating.’

While everyone was still sniffing, I announced that I would sing some joyful songs to lighten the atmosphere. I didn’t feel comfortable singing joyful songs at funerals, but it was the custom. The farewell belonged to the past. Life had to go on with joy and hope.

After a loud round of applause, I moved swiftly but quietly to the back of the courtyard, from where I could see attendants placing food on large trestle tables.

The aroma of the hot food filled the air. There were no signs of sadness on people’s faces any more. They started staring at the dishes and picking at food with their chopsticks. My stomach rumbled.

I looked around for any familiar faces. The village barber caught my eye. I would tell him people thought my hair was nice when I visited him next time.

The feast after the funeral was called a tofu banquet. The funeral dinner used to be a vegetarian meal with tofu as the main ingredient. Hard or soft, fried, boiled or steamed tofu, made from nutritious soya beans, showed respect for both the dead and the living. In recent years, more and more meat and fish has been added to the funeral meal, but the banquet wouldn’t be complete without tofu. After all, it’s white, the colour of death.

I wouldn’t stay for the tofu banquet, but I would be given some food to take away. Nobody would mind if I stayed, and I would stay if I had known the dead person well. Great-Great-Grandma was much older than me, so I had never had a chance to get to know her properly. I had been fond of her, but she had probably never noticed me.

The young woman handed me a white envelope while people were queuing up for their china bowls. I could feel the stack of cash inside the envelope was thick. Thick enough.

The husband would be pleased.

Chapter Two

Although I lived only a stone’s throw from the reception, I was driven home by a car arranged by the uncle of the young woman. The respect they showed me reflected the filial piety they had for Great-Great-Grandma.

As the car was about to move, the young woman rushed up and knocked on the window. ‘You forgot your food.’ She waved a paper bag at me.

Once I was inside my house, I went straight to the bedroom to get changed. The husband was sitting in the middle of the bed wearing his outdoor clothes, fiddling on his phone.

‘I’ve told you enough times. You shouldn’t come home in your horrible white funeral gown. You’re cutting years off my life. Stupid woman.’ He was angry.

I should have expected him to be home at this time. I removed my gown and made for the bathroom.

While I was in the shower, I lathered my body again and again, to wash off all the bad luck from the funeral. But I couldn’t stay here too long, as the husband would insist I was wasting water.

I was upset when the husband first called me a ‘stupid woman’. I knew I wasn’t stupid, but it had become his catchphrase. It washed over me now.

I unwrapped the longevity china bowl I had been given and placed it in the cupboard. Now there were twelve of them, all similar, with the Chinese character for ‘longevity’ printed on the side.

The longevity bowls were only given away by the bereaved if the deceased was elderly, a blessing for others to live such long lives.

I never use the bowls, as I worry I might break them, which is considered bad luck. But sometimes I would open the cupboard and admire all my precious longevity bowls.

I heated up the food I’d brought home from the tofu banquet and dished out two plates.

I called out to the husband, ‘Dinner.’

He came out and sat down. ‘Dinner? I haven’t had lunch. It’s 4:30 now.’

I explained, ‘The funeral ran on for much longer than I expected. Shall we call it an early dinner?’

‘Are you trying to starve me?’

‘You should have gone to the funeral. Nearly the whole village was there.’

‘I didn’t want to hear you crying and singing. You bring food home anyway.’

‘We can have some snacks later. I’ve got some rice biscuits for you.’

‘White rice biscuits? Funeral nibbles. I don’t want any.’

‘They’re not cheap in the shop.’ I knew he would eat anything if it was free.

The husband stirred the five-spice beef cubes with his chopsticks, ‘How much did they pay you?’

‘I didn’t count, but … they said they would pay me 1,399 yuan.’

‘Have you thrown away the white envelope?’ He frowned.

‘I’ll throw it away after dinner.’

‘Will you give me the money now?’

‘I will.’ I started eating. ‘But after dinner.’

He was hungry. I was hungry too.

We finished our food in silence.

When I took his dirty bowl to stack on top of mine, I noticed a couple of grains of rice on the lapel of his jacket. In the past, I would pick the rice off for him, but not now.

While I was washing the dishes, the husband had already counted the money.

‘1,699 yuan,’ he said.

I felt contented and proud. I was paid extra when my clients were satisfied with the job I’d done, and I often got paid extra. My ability to cry and sing well had earned me a good reputation. People thought it was a genuine, heartfelt performance. I didn’t care how much I was tipped; the extra money showed how much trust people placed in me.

This had been a short-notice crying job. One day Great-Great-Grandma felt tired, so she lay down in her bed. Her card-playing friends went to see her because she hadn’t turned up for the game. When they found her, she refused to go to hospital. She wouldn’t eat. A few days later, she died.

Many deaths happen at short notice, and some at no notice at all. The family of those deceased were usually in shock as well as being grief-stricken, so they needed a great deal of care and consideration. I was ready for all scenarios; the longer-notice relatives of the deceased deserved just as much care and consideration.

There were stories and secrets that I would never have heard if I weren’t a funeral cryer. A lot of the time, mourners needed to share their stories, and they wanted to do it with someone who didn’t know them too well and who wouldn’t share the stories with anyone else. Someone like me. To these people, I was usually a stranger. Most of these stories were tragic or unpleasant – I was always receptive to them, but I hardly made any comments. I was a pair of ears, that was all.

Miserable stories made me feel as if my life wasn’t all that terrible; all the stories added a little excitement and life to my boring existence. My head was full of these tales, but I kept them all to myself.

The husband threw me five 100 yuan notes for housekeeping after he put most of the rest of the money away.

Over thirty years ago, when we were studying in the same classroom, he was nice and quiet. I hardly knew him then, and I never thought that one day we would eat and sleep together. I couldn’t believe he was the same person I knew when I was young.

The husband always moaned that I was bringing home bad luck, but he never said the cash I made would breed misfortune. When we argued, he would casually say I smelt of the dead. However, when he removed my knickers, it was a different matter.

When he was inside me, my body was rigid. Luckily, it was only a matter of a couple of minutes, so if I kept my eyes shut and stayed still, it would be over soon enough. He never knew whether I felt pain or not, because he never asked and I never said anything.

For him, it was like … I actually didn’t know how he felt.

I didn’t care.

Chapter Three

I had been crying at funerals for a living for about ten years. It wasn’t my choice, but there were no better jobs available. I had to find a job, as the husband and I were both out of work.

In the village, most people around my age had no jobs. They spent a lot of time in the fields allocated by the village committee, growing rice, onions, sweetcorn, potatoes and sweet potatoes. We used to have some fields, but they were confiscated by the committee on grounds of neglect. We were now amongst the very few people in the village who had to buy rice and flour. I wish I could turn back time. I would have done all the hard labour needed to keep the fields.

There were hardly any young people left in the village, as there was no future for them here. Who wanted to live in a smelly place? They had all gone to cities for education or work, including my own daughter. Some of the more ambitious young people had gone abroad.

Once young people had families, they would send their children back to live with their parents to save on childcare costs. If they earned good money, they would ask their parents to move to the cities to take care of their households. But that rarely happened. It was hard to survive in cities, unless they happened to make a fortune, which was very unlikely for the majority. Over the years, two or three grandmas in the village had been abroad to look after their grandchildren, which caused much envy at the time.

I was born in this village. It’s called xī ní hé cūn, West Mud River Village. There was enough mud in the village, but there was no river. I had asked Mum and Dad whether there was ever a river before. The answer was no. I then asked why river was in the name of the village. They said nobody knew why, or cared what the village was called. But I cared. Whenever people asked me where I was from, I felt embarrassed. I hated the thought of people laughing at such an ill-fitting name.

There were two mountains that formed the backdrop of the village – one was called South Mountain and the other North Mountain. They were useless mountains. People used to bury their ancestors on South Mountain, but it wasn’t in use any more. In theory, Mum and Dad were allocated grave plots on the mountain by the village committee, but these days people would buy a plot in the graveyard instead. Then there was North Mountain. There was nothing there, apart from some rocks and maybe a handful of trees and plenty of weeds. I had never been to the mountains, and most people in the village had never been there either.

The husband wasn’t home. He had snuck out when I was in the backyard.

Mum and Dad used to keep two pigs in a pigsty in the backyard. The filthy pigsty was still there, in the corner of the backyard. There was a chicken run too. We used to have our own eggs and chicken meat. We stopped raising pigs when the husband and I got married. He said it was too dirty and smelly, and it was hard work. Mum insisted on keeping the chicken run. Three years ago, after she moved to the brother’s, we ate some chickens and sold the rest.

There was plenty of room to grow vegetables in the backyard. I mainly grew what Mum used to grow, like onions, beans, snow peas, mooli, potatoes and sweet potatoes, together with some green vegetables, since they were easy to look after. Stir-fried sweet potato leaves were the most delicious.

We had always been tight for money when I was little, so being thrifty was second nature. I used to think money wouldn’t be tight one day, but sadly it still often was. I would sit on the bench in the backyard admiring my vegetables. I couldn’t help trying to work out how much money I had saved. I wouldn’t make a fortune through growing my own vegetables, but it was a little help.

The husband never told me when he went out. He must have taken some cash and gone to play mah-jong. He always boasted he was better than most of his friends. Some would play mah-jong overnight – sleeping and eating were the only other things they did, but he would at least come home for dinner. I thought perhaps he could come home after dinner, which meant I wouldn’t have to cook for him, but of course I never suggested that.

*

People used to come to our house to play mah-jong until I started working as a funeral cryer. They used to enjoy coming. I would prepare snacks and occasionally watch them play. They would donate a fraction of their winnings as ‘rent’. To be honest, I didn’t like to have people around playing mahjong, but it seemed they liked the husband and me. It was important to be popular in a village where everyone knew everyone.

I’ll never forget the moment when people stopped coming to our house – in fact, when they left. I had just been offered my first funeral-crying job, so I was excited. There were people playing mah-jong in our house, and I told them about it. As soon as they heard the news, they put the mah-jong tiles back in the box, got up and walked out.

Now that I brought bad luck and I smelt of the dead, nobody would step into our house to play mah-jong or chat. I didn’t like mah-jong, but I liked to have some female friends over, eating snacks and gossiping. As for the bad luck and smell, I couldn’t disagree too much. You could say it was superstition, but when someone was associated with death constantly, it was understandable that people wanted to keep away from them. I wouldn’t go to a funeral cryer’s house myself.

As I was home alone, I was able to practise my singing. The husband complained that my singing sounded like a ghost howling, so I wouldn’t sing when he was around. I guessed he’d forgotten that he used to tell me I was a good singer.

I didn’t need to practise, since nobody at funerals would care about the quality of my singing. The clients would prefer to have a cryer who could sing well, though. The funeral goers paid money to go to ‘eat tofu’, so it made sense that they would like to return home satisfied, as if the whole experience had turned into an occasion for entertainment.

I hated singing at funerals, even though I was paid to do it. After everyone queued up and bowed to the body in the coffin, the calm and solemn funeral turned into chaos. No one needed to show their grief any more. Some funeral cryers would bring a random band to play loudly, and often out of tune, but I would never do that. Having to sing joyful songs was bad enough.

There was always some pressure for funeral goers, as it was hard to show the right level of sorrow. You didn’t have to be as sad as the surviving family. In fact, you didn’t even need to be sad, but it’s kind to show that you care. As the last part of the funeral, joyful songs would perhaps bring some relief, if not joy, into the air. After being engaged in the crying, I found them awkward.

Being a funeral cryer wasn’t easy, as my income relied on dead people. These days, people were living much longer than in the past. It wasn’t that I was hoping for people to die younger, but whenever someone died, it was my chance to earn some money. More deaths meant more money for me. I heard I was the best funeral cryer within twenty kilometres. There were not many cryers around anyway.

I took a nap in the afternoon. I hadn’t slept well. I never slept well after a funeral. The waxed face in the coffin would appear before me for several days after the event. I always tried not to invest any emotion into funerals. I shed tears, but I didn’t cry. Nevertheless, the energy required left me feeling exhausted. When I sat down at home after a funeral, sometimes I couldn’t tell whether I was feeling down or simply drained.

I checked the vegetables in the backyard. There were no more garlic leaves left in the pot. I would have to wait for three or four days until they were long enough to cut again. Maybe I could go about the village to find some wild garlic. Wild garlic leaves are slightly wider and they taste more delicate. They weren’t difficult to find along village paths.

I grabbed a small plastic bag and left home.

We still have mud paths in the village. They look okay on dry days, but of course they’re grubby and dirty and slippery when it is wet. Towards the entrance to the village, a couple of paths have been concreted and lead to the tarmacked main road outside the village.

‘Is that you?’ I heard someone’s voice and turned around.

‘Auntie Fattie.’ I greeted her and stopped.

Auntie Fattie was a thin woman, a friend of Mum’s. She must have been fat before, but I didn’t remember.

‘What are you doing? I hardly see you.’

‘I’m going to look for some wild garlic.’

‘Wild garlic? Are you so tight for money? Nobody eats wild garlic any more.’

‘I don’t use it that often.’

‘Are you still crying for funerals for a living?’ Her tone was stern.

‘Yes.’

‘A woman from a decent family shouldn’t do anything like that.’

‘I need to earn money.’

‘Yes, you do. Your husband is useless.’

‘He’s a clever man.’

‘Cleverness can’t feed you. Money can.’

‘We’re fine for money, Auntie Fattie.’

‘I hope so. By the way, do you always wear clothes like these?’ She looked at me from head to toe.

‘They’re my daughter’s old clothes.’

‘They’re too tight for you. Look at the blue trousers you’re wearing. People can see the shape of your bottom and your legs.’

I didn’t say anything. There was nothing I could say.

‘Don’t be upset. I saw you grow up. I’m your elder.’

‘I know, Auntie Fattie.’

‘They say you’ll bring us bad luck, but I don’t care. People say I’m a cursed woman. I caused two husbands to die.’

‘You didn’t do anything, Auntie Fattie.’

‘Don’t wear those trousers,’ she said, ignoring what I had said.

‘They’re comfortable.’

‘Do men like them? People say you go to the barber shop too often.’

‘I don’t. I only go when I have to.’

‘Nobody has to go to a barber shop.’

While I was cooking dinner, I was humming some songs. Even if I wasn’t a brilliant singer, I loved singing. It was like communicating with myself. I preferred to sing slow, gloomy songs. They usually made me feel less sad.

I had picked a handful of dwarf beans and thawed out some minced pork. The dish never failed when I cooked them together with some soya sauce, garlic and chilli. The husband liked the dish too. When I could, I would cook something he fancied.

‘The dishes smell nice.’ The husband picked up his bowl of rice and dug into the bean and pork dish with his chopsticks.

‘Try the hot and sour potato strips.’ I moved another dish nearer to him.

‘I made some money at mah-jong today. I don’t always lose.’

‘No, you don’t.’ I was tempted to say, If you don’t play, you’ll never lose, but I didn’t.

‘By the way, have you replied to the daughter?’ He changed the subject.

‘No. I haven’t decided what to say yet.’

‘Are you not going?’ He stared at me.

‘I’d like to, but what about my job?’

‘Your job? You don’t have a proper job.’

‘I cry and I get paid, so it is a proper job.’

‘You sometimes do some work. You take advantage of dead people.’

‘I don’t take advantage of anyone.’

‘You’re useless when no one dies.’ He raised his voice.

‘At least I’m useful when someone dies.’ I also raised my voice.

‘You’re talking back, stupid woman.’ He stood up and hurled his bowl to the floor.

The china bowl shattered on the ceramic tiles. There was rice everywhere.

I looked at the mess, but didn’t move.

‘You wasted a bowl.’ He pointed at me. ‘I wouldn’t have smashed it if you hadn’t talked back.’

‘I didn’t talk back.’

‘Give me another bowl of rice.’ He sat back down.

So, he was still hungry.

When I was clearing up the mess in the kitchen, my throat felt blocked. I wanted to shout. What would the husband do if I had smashed a bowl? I wanted to talk to someone. I wanted to shout. Would the daughter listen?

I couldn’t help thinking about the daughter. I hadn’t seen her for over six months. She lived in Shanghai with her boyfriend. He was a taxi driver and she was a masseuse. However, the husband thought she now worked in a supermarket. He wasn’t pleased when the daughter moved to Shanghai to work in a massage parlour, since some masseuses had a reputation for selling sex. He nagged me to tell the daughter to quit her job, so the daughter and I decided to lie to him and told him she’d got a new job as a shelf stacker. I didn’t think the masseuse job was a problem as I trusted the daughter. On the other hand, it was important to have a good salary if you lived in Shanghai. Masseuses made plenty of money, although the hours were long. She was pregnant now, so she wasn’t really fit for her job, either as a masseuse or a shelf stacker.

The daughter had asked us to discuss her plan: l would go to Shanghai to look after her until she gave birth and bring her and the baby to our village afterwards. She would stay with us for about two months, then leave the baby here when she returned to work.

I wasn’t looking forward to that. I was happy to help her out, but I didn’t want to keep the baby in my home. When I had to look after the baby, I wouldn’t be able to work as a funeral cryer, since the daughter wouldn’t let me. She never liked my job. She might think I would bring bad luck to her baby if I had contact with dead people.

When the daughter was still at school, she had been bullied because of my job. Some children told her I would shorten people’s life span, so they didn’t want to play with her. Her stationery would sometimes disappear, but would reappear later. Several times, she couldn’t find her packed lunch. She begged me many times to stop being a funeral cryer. I wished I could, but we needed money. I wanted to speak to the teachers, but she said it would only make matters worse. It seemed the only solution was to give up my job.

It was easy for anyone to say that they didn’t want me to be a funeral cryer, but who would make money for the family? The husband didn’t have a job. I could help people in the fields or work in a shop in town, but the wages were meagre. Funeral crying didn’t sound like a good job, but the money wasn’t bad. I had skills for crying and singing not many people had. Even now, the daughter couldn’t afford to give me what I could earn. I didn’t know how much she earned, but she spent more than me and also wasted a lot. She might be willing to give us some money for the extra expenses when the baby was here, but even that wasn’t guaranteed.

Most importantly, the daughter needed to apply for a marriage certificate. There would be no maternity leave for her or birth certificate issued to the baby without the marriage certificate. She had said she would ‘do it soon’ several times, and I didn’t know what she meant by ‘soon’. I had heard that word many times from her mouth in my life, but it had a different meaning from my ‘soon’.

Sometimes, I thought maybe she didn’t want to get married. When she was little, whenever the husband and I argued, I could see her nervous expressions.

‘When’s your next crying job?’ The husband lit a cigarette after he poured some sunflower seeds from a paper bag, his feet on the coffee table in front of the sofa.

‘I don’t know.’ I shook my head.

‘I hate this singing programme. Their singing is as bad as yours.’

‘I know I don’t sing as well as you, but people pay me to sing.’

‘They’re as stupid as you. Where’s the remote control? I can’t stand their singing.’

I said nothing, but handed the remote control to him.

‘These days people are living too long. Look at those old people in our village. I don’t think any of them will die soon.’ He lay on the sofa, frowning.

‘No. Most of them are healthy.’

‘You should expand your business to cover a bigger area. There aren’t enough people to die around here.’

‘Maybe I could sing at weddings.’

‘Nobody would want you at weddings. You’re too old and too ugly. You also give people bad luck and you smell of the dead.’ He wiggled his legs.

The husband walked out of the living room, leaving cigarette ends and sunflower-seed shells everywhere. I didn’t want to tidy up after him, but I knew I had to.

All right. I am too old and too ugly. I give people bad luck and I smell of the dead.

Did he know what he looked like and smelt of?

What did he give people?

Chapter Four

There was a crying job in a relatively distant town, hú táng zhèn, Lake Pond Town. One of the guests at a funeral had found me through word of mouth. If I agreed to do the job, she would send a car to collect me to discuss the funeral arrangements. It would take about forty minutes to get there by car and I would be paid from the moment I left my doorstep, so I said I would go.

I was curious about the name hú táng zhèn, Lake Pond Town.

‘Is there a lake or a pond in this town?’ I asked the driver, a tall, dark young man.

‘I’ve no idea. Why do you want to know?’ he replied.

‘Well, there’s no river in my village, but its name has “river” in it.’

‘My hometown’s called mă shān’ – Horse Mountain – ‘but we don’t have any horses or mountains in our village.’

The client welcomed me at the door of a large house in a western-style villa development. It was called tài wŭ shì xiăo zhèn, Thames Little Town. It wasn’t far from sài nà xiăo zhèn, Seine Little Town. There were two traditional stone lions guarding the entrance to the house.

The client was much younger than me.

‘My husband was extremely rich, so you’ll be paid well,’ she said, without looking at me.

‘Thank you.’ Nobody needed to be extremely rich to pay me well.

‘I’m not that sad.’ She fiddled with one of her rings.

‘I’m sorry.’

‘I haven’t cried since he died.’ She met my eyes for the first time.

‘It happens sometimes. Don’t worry.’

‘I don’t know how to fake grief.’

‘You don’t have to fake it. It’s inside you.’

She shook her head. ‘No, it’s not there.’

‘It’s not hard to cry.’

‘But I have to cry genuinely. People will be watching me. They’ll criticise me.’

‘I’m sure you’ll cry genuinely.’

‘If they don’t think I’m devastated, or devastated enough, they’ll gossip about me.’

‘Show them you’re devastated, then.’

‘That’s why I hired you. If they think I’m not sad enough, they’ll make up stories about me. They’ll take the money away from me.’

‘I’ll show you how to cry.’ I reassured her.

*

Her driver brought us some tea and nuts. She smiled at him.

‘My driver’s a good man. He helps with our household chores too, as there’s not much driving for him to do.’

‘He’s nice.’

‘Yes. More useful than my husband.’

‘But your husband made the money.’

‘Yes,’ she said. ‘We were married for nearly twenty years.’

‘You married young.’

‘Yes. We grew up in the same village. We went to Dalian to look for work when we were both nineteen.’

‘What did you do?’

‘He learnt to be a tiler and painter, and I did the cleaning.’

‘I used to do cleaning in Nanjing,’ I told her.

She nodded. ‘Hard work, but we saved a lot of money.’

‘You must have been happy.’

‘We loved each other. At least I always loved him.’

‘He must have loved you too.’

‘Maybe. He died in a car accident in Beijing, with a young woman in the car.’

‘Weren’t you in Beijing at the same time?’

‘No. He said he was going to a construction materials exhibition.’

‘Maybe she was a client.’

‘They were checked into a hotel as husband and wife.’

‘I’m so sorry.’

‘I felt my heart was broken, but I didn’t cry.’

‘Did you tell anyone in your family the truth?’

‘No. Not even a ghost.’

‘Did the woman die?’

‘No.’

‘Was she injured?’

‘Yes, badly. She’s probably still in hospital.’

‘Do you think she’ll recover?’

‘I don’t want her to die.’

‘You’re a kind woman. I’ll make sure the funeral goes well.’

‘Make sure the funeral-goers think my dead husband and I were a loving couple.’

‘I will.’ I nodded.

‘Maybe we were a loving couple.’

I knew it wouldn’t be an easy job, but I would earn around 1,500 yuan. That would cover two months’ housekeeping expenses for us.

I would never tell anyone the guilty pleasure I felt from time to time between funerals.

As a funeral cryer, I had met all kinds of people, including rich people. Sometimes I was a little jealous of the rich men’s wives, since they didn’t have to work and they had all the money they needed. I thought I would look beautiful too if I wore expensive clothes and jewellery. Although the husband said I was an old and ugly woman, I grew up hearing people say I was pretty.

However, most rich women I had met were widows. My own husband wasn’t close to being rich, but at least he was alive.

I didn’t have money to buy any expensive jewellery, but I could buy some new clothes for myself. I’d been wearing the daughter’s old clothes for the last few years. She had too many clothes and she would throw the old ones away if I didn’t take them. At the moment, I was wearing her grey jumper with the tight jeans.

When the driver brought me back after the meeting, the husband wasn’t home, which was a bit unusual since it was dusk and he hardly ever returned after dark. I felt relieved, though. If he were at home, he would complain I was late and he was hungry.

I had no idea when the husband had arrived home, because I was half-asleep when I heard the bedroom door open.

He smelt of alcohol, sweat and cigarettes. He doesn’t drink a lot, but I buy beer for him regularly – there are always several bottles in the kitchen cupboard. He must have been drinking with his mah-jong friends. He drinks when he is happy or unhappy. I wouldn’t ask him as I was worried he might shout at me if he was unhappy. I didn’t know how to make him happy these days. Maybe I had never known.

When the husband shouted at me or threw things around, I was scared. He said there was nothing for me to be frightened of as he wouldn’t hit me. He said I was lucky – in the countryside, it was common for men to slap their wives, often for no reason, all the time. They just could. Did I have to be grateful that he didn’t hit me?

‘You woke me up.’ I sat up.

‘I don’t care.’ The husband threw himself on the bed.

‘You’re drunk.’

‘I’m not, you stupid woman.’ He raised his voice.

I turned on my side.

He pulled the duvet. ‘Why didn’t you open the front door for me?’

‘I didn’t hear it. I was almost asleep.’

‘It was cold outside. Luckily I found my keys in my pocket.’

He took his clothes off and climbed under the duvet. Within minutes, he started snoring.

I didn’t want to sleep next to the husband when he stank of alcohol, but I had no choice.

To him, I didn’t seem to exist in bed unless he wanted sex, and it sometimes happened after I came home with money from a funeral. Did he think he was doing me a favour? Or was it a deal? I gave him money and he provided sex? Perhaps his mood was raised by the money.

In the last ten years or so, I’d been the breadwinner in the household. When we both had to look for jobs because we couldn’t make ends meet by doing our comedy duo, he didn’t try very hard.

I had bought some newspapers with job adverts.

‘We can move to Dalian,’ I suggested.

‘Dalian is too expensive.’

‘But we can make more money. We wouldn’t spend much ourselves.’

‘People will look down upon us.’

‘Which people?’ I didn’t mind.

‘People. They have money.’

‘We’ll have money if we work hard.’

‘We’ve worked hard, but we’re still not rich.’

‘We’re not poor. We make more money than most people in our village.’

‘It’s not my village. It’s your village.’

‘We’ll be poor soon if we don’t find any work.’

‘It’s embarrassing to look for a job now, I’m too old.’

‘It’ll be embarrassing when you’re properly jobless.’ I handed the newspapers to him.

‘You can go to Dalian on your own.’ He scrunched the papers up and threw them on the floor.

Then the brother offered to let him use one of his mopeds for free to transport people, but he turned it down.

‘Does he think he’s my boss?’ He was annoyed.

‘He’s not your boss. You don’t have to let him share your profits,’ I explained.

‘So he pities me.’

‘He’s trying to help you.’

‘I don’t need his help. I’m not a beggar.’

I was lucky enough to find a job soon, a bad one, as the husband put it. I wasn’t excited about being associated with death, but I liked the financial security it provided. Although the husband didn’t work, he demanded I give the money to him. He said he was looking after the money for both of us, as he was the man and he was in charge of the household. Back in the days when we were a comedy duo, he was the one who dealt with money matters as well.

Whenever I gave the husband money, he noted it down in an exercise book from the daughter’s school years then put it in the shoebox in the drawer of his bedside table. He would go to the bank in gū shān zhèn, Solitude Mountain Town, to deposit it when the shoebox was full. He added a lock to his drawer a couple of years ago. He explained the lock was to prevent thieves, not me, but he didn’t give me a key. I had thought about asking for a key, but I was worried he might accuse me of not trusting him.

He told me the money I made didn’t belong to me; instead, it belonged to the family. I didn’t mind who earned money or whose money it was, since I agreed that the money belonged to the family. However, I might feel a little better if I wasn’t the only person who was making money. I’d be happy if he showed some responsibility. If not, he could at least show some gratitude.

He liked to criticise me and made sarcastic comments about me and my work. Why didn’t he look for another job himself? We lost our last jobs together, and I found a job soon after that. If he couldn’t make money like a man who was in charge, he’d better shut up and stop blaming the woman.

The daughter had texted again, asking when I would make the trip to Shanghai. Did she assume I would go? I knew it would seem wrong if I didn’t. I wouldn’t say I loved crying at funerals for a living, but the money was important for the family. There wouldn’t be any crying work in a modern city like Shanghai.

I couldn’t really say ‘no’ to the daughter, as I could still feel my pain from when she was bullied by her schoolmates. I was still trying to compensate for the tears she had when she was at school. Would I ever stop feeling guilty over it?

Since I started my crying job, I hadn’t been to anyone’s house except for my elder brother’s. He lived in dà lóng zhèn, Big Dragon Town, a town about ten kilometres away. I went there several times a year to visit Mum. She used to live with us, but she moved to the brother’s after Dad was sent to the care home.

The brother didn’t mind my visiting, but the sister-in-law didn’t like it. They had a son, and she thought he shouldn’t be exposed to my deadly aura. To make her happy, I gave her vegetables from my backyard, homemade pickles and sausages. I had also given them one longevity bowl each to bless everybody and to make up for the bad luck I brought.

Apart from funerals, the place I visited most frequently was the grocery shop in the village. The husband used to do the shopping when I first started my crying job, but he soon complained that grocery shopping was too menial for him. I was happy to take over, because it gave me a chance to get out of the house.

I liked the fruit and vegetable section in the shop best. Everything was so colourful and I could smell the freshness of the soil and leaves. Whenever I picked up several items and put them into my basket, I could imagine their tastes on my tongue.

There were no restaurants or cafés in the village, as there was no need for them. Most of the villagers could cook well enough, and they weren’t fussy about food. When there was a wedding or a funeral, some amateur chefs would be hired to cook banquets.

The only other amenity was a small barber shop on the path leading to the tarmac road. I went there regularly to have my hair done, as it was never busy. I always felt welcome, and the barber never said that I brought him bad luck or that I stank of the dead.

The barber, who was also the owner of the barber shop, was a good-looking man in his, perhaps, late forties. The shop was the front room of his house, with a wonky dining table in the far corner for his hairdressing tools.

The barber moved here several years ago when he married a widow from our village. I believed she was about my age. She’d married a man in our village when I was in Nanjing, so I’d only known her briefly. Then she and her previous husband moved away from the village for many years. When she moved back with the barber, I still barely knew her. The barber limped a little, although you wouldn’t notice anything when he wasn’t walking.

Sometimes when I passed the barber shop but didn’t need a hairdo, I almost wanted to stop to say hello and chat to the barber, but I never did.

I remembered the conversation the barber and I had when I visited last time.

‘Your hair’s nice,’ he said. His voice was deep and gentle.

‘No. It’s thin and dull.’

‘It’s fine, not too thin. Everyone’s hair is different.’

‘I used to have much more hair.’

‘We all lose some hair as we get older.’

‘And the hair goes grey.’

‘That’s why you have to come to my shop.’ He smiled.

‘I hope you have more customers.’