Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Muswell Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

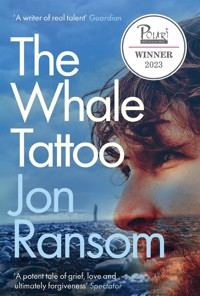

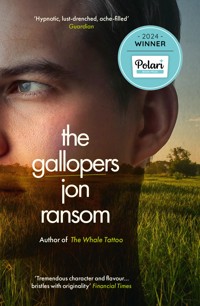

Winner of the Polari Book Award 2024 From the author of The Whale Tattoo, Winner of the Polari First Book Prize 2023 1953. Eli is nineteen years old and lives alongside a cursed field with his strange aunt Dreama. Six months before, his mother disappeared during the North Sea flood. Unsure of his place in the world and of the man he is becoming, Eli is ready to run. Shane Wright is a man with plenty to hide. Caught in a complicated relationship with Eli, Shane is desperate to maintain the double life that he has created for himself. Then Jimmy Smart appears. Jimmy Smart, the mysterious showman who turns the gallopers at the fair. Under his watchful gaze, Eli discovers a world he knows nothing about with rules he cannot understand. Three men bound together in a blistering story that spans 30 years, from 1953 into the 1980s and the AIDS epidemic, The Gallopers is a visceral and mesmerising novel of deceit, desire and unspeakable loss.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 205

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE GALLOPERS

Jon Ransom

For Mark Craig Ackroyd

Contents

1953

Just as the moon shining in a bucket full with water isn’t really the moon, I am something other than I appear to be. Something that keeps me restless. Hauled into night again and again to our field. An arrow-shaped piece of land belonging to Aunt Dreama and me. Since the flood, since that wild night when the moon was a different colour altogether, half the farmers have turned against us. The rest murmur mistruths about my mother. Who was washed away. Though I have to swallow the lies. Put my back to those who hate me. Gather the stones that boom through the windowpanes at daybreak, collected in a pile at the foot of my bed. I tell Dreama we should pack up. Move to another town. Any town. Find someplace shiny where nobody knows how cunning dirt can be. Though Dreama won’t give in to the situation, or hear of quitting the field. Not now Jimmy Smart is living out in black barn stirring everything up. Fortnight past he drove Peg over from Wolferton station. Two of them arguing like crows. Her believing he almost killed them dead, them lucky not to be at the bottom of Coalyard Creek. Jimmy Smart had shrugged like it was no big thing. The whole while I’d looked on everywhere but Jimmy Smart’s gaze. Might be my own would have given me away. When Peg had told Dreama windowpanes cost something, that she could do worse than let him live out there in black barn, Dreama sucked on her Woodbine for the longest time while a big bluebottle buzzed about her head. Inside my own head, I’d already seen it all. Knowing this stranger, who’d not long been hauling luggage at the station, would disrupt everything worse than the flood, a rush of water that swept over all the dirt around here but our own. Dreama sighed. Her paying Peg some debt these women had held close. She nodded towards black barn. Told Jimmy Smart where to find the fold-out bed. And that’s how I find myself kneeling before this open window holding my pale dick in moonlight, while watching Jimmy Smart wash himself off outside black barn. His bare skin wet with cool water from the tin bucket. Until his white underdrawers are soaked clear. Now I’m dazed. Dizzy with desire. Rushing my palm against my mouth to stifle the groan. Afterwards, when my balls are empty and black barn quiet, I go outside. The night is still, folded all around me and the wooden planks. The air heavy against my skin. Dirt warm beneath bare feet. I dip my hand into the bucket breaking the moon into different pieces. Too many to count. Scoop up a handful and drink. Even though it’s just a reflection I try to taste the moon turning around and around in my mouth. Nothing. And drift off into the field, where I put my back against the ground. Down in the coolness I tell myself I’ll stay away from the mysterious showman Jimmy Smart. Keep quiet around him. Because I know not even swallowing moonlight can wash away my sissy mouth, that has gotten me into more misfortune than not.

Don’t talk much, do you? Jimmy Smart says.

Not too much, I say.

Words don’t start where you think they do. Or come from where you imagine. Cuz you’d be wrong in believing they slide down from your head into the back of your throat. All words run upwards from the belly, hitchhiking on your breath.

That—true?

Reckon so.

But—

Go on—

How’d they turn out—sounding the way mine do?

Mystery to me.

You mean—you don’t know? I say.

It’s a dilemma for sure, Jimmy Smart says.

Like a sparrow torn from the flock after a fierce wind, I worry Dreama has gone astray. Since the flood it’s happened more and more. Arising as the wideness of her eyes, their blue foreseeing a sudden something invisible to me. I know the broken windowpanes are disrupting the house, and I’ve yet to discover whose hands hurl the stones. But I will. And when I hear a hammering below, for a moment I believe it might be yet another. Though instead of finding pieces of glass glinting, Jimmy Smart is stood at our backdoor. Breathless. Boot laces untied and bare-chested. His mouth regretful without saying a word. And when he does speak it’s to tell me to bring a blanket and no more. I fetch Dreama’s purple knitted shawl from the back of her chair. Tug on my boots. Trail behind the showman out to the field. He moves quick. Like he’s been heading somewhere his entire life. It’s more than the pace he keeps and the way he doesn’t care to glance back over his shoulder. Along the way I wonder about the scar on his back, sickle-shaped and a palm wide. How it might feel beneath the tip of my forefinger. Before long we’re into the field. Damp grass stirring in early light. Beyond the field and further there is a stretch of indigo mountain that isn’t really there. These illusions follow Jimmy Smart around. At the centre of our field where the grass doesn’t care to grow, we find Dreama stark naked. Her turning circles. Talking to ghosts. I feel bashful all of a sudden. But Jimmy Smart doesn’t seem to mind, and I suppose that must be because he’s seen his share of bare women. He takes the shawl from my hands and holds it out like a sail, catching her in a fold of purple. Dreama surrenders. Her gaze empty, except for the colour of cornflowers. And Jimmy Smart steers her towards the house, through the backdoor, and pulls out a chair. He wants to know if I need anything more. I shake my head, not trusting my mouth. Light Dreama a Woodbine and place it in her hand. Metallic smoke whirls about her yellow hair. And when she exhales, the shawl slips down until I can see one pale breast. Dreama is something else.

I’m not a child, Dreama says.

I know that, I say.

Then don’t treat me like one.

What would you have me do?

Leave me be.

Out in the field—like that?

It’s my field.

Not any longer—

You ever wonder what’s after?

I never wonder that.

Eliza could come back yet.

No—my mother’s gone.

I can feel her. Right here. In my chest. Like a stone, Dreama says.

We don’t need any more of them, I say.

Shane Wright’s cheeks are bluish all the time. Comes from him having coal-coloured hair beneath pale skin. The light this day is bluish too, laid about on each and every surface. There is blue on the Heidelberg press, that sucks and sighs steadily. Blue steel shelves with blue tins of ink that are really black. And stacked in wooden racks piles of printed paper a surprising shade of indigo. Light is clever like that. I wipe sweat from my forehead with the sleeve of my overalls. Even with every window hung open the air inside the printshop is unlike anywhere else. Heavy with the heady scent of ink on paper, set-off powder and solvent. Beneath this sweat from the men who turn everything, disturbing my nostrils. I am hypnotised by smell. Unlike light, smell gets everywhere. Underside, inside. There’s nowhere it can’t roam. I care for the smell of clean palms, a spent match after lighting my Woodbine, and the middle of Shane Wright’s chest where his hair is thickest. Yet today I can’t stand it. And tell them I’m going outside. Where I find the yard is also bluish, and this bothers me too. Dreama would claim it means something. Something more than superstition. Might be there’s truth to it. As when I drift back towards that wild night and the hours beforehand, there was an odd yellowish tinge to the twilight. Something burning beneath. Even the townies talked of it in the days following the flood, when the water was black and calm. Dreama had sworn it was the same colour I turned as a newborn. Then Shane Wright is out in the yard alongside me, interrupting my thoughts. We smoke our Woodbines and watch the yard. There’s nothing much to look at. Narrow and six-foot walled on either side, with a privy behind a blue door at the far end I’m considering. But if you stand still long enough you’ll see pretty purple flowers spring from between red bricks. I consider bringing one home for Dreama. Though Shane Wright has other ideas. He’s licked his thumb and is rubbing ink he tells me is ruining my chin. His eyes wrinkled from squinting at the sun. Stirring the situation. I forget about my need to urinate. As I’ve no desire to piss in my own face.

Been watching you all morning, Shane Wright says.

I know— I say.

You’ll stay after then?

I can’t—not today.

How come?

I promised Dreama something.

What’s that then?

Nothing—important.

Heard about that showman you have living out in black barn. Don’t see why he’d want to work at the station. What about his own people?

None of my concern— Suppose everyone knows he’s beside our field?

Can see it’d be handy having him around.

I guess—

He have a name?

Jimmy Smart.

What’s he like? Shane Wright says.

Like nobody around these parts, I say.

The iron bridge is high enough to hurl ourselves off. The water deep enough. We strip beneath the moon, bright as a dinnerplate licked clean. I fold my shirt and trousers. Jimmy Smart grins, ditches his clothes beside tall grass wild with night music. He is distracting, being bare-arsed and not bashful. Though my heart’s hammering I’m glad I lied to Shane Wright about a promise I hadn’t made to Dreama. That I agreed to drive out to the river with the showman. On the ride here he’d talked about the station. Working for Peg alongside her daughter, Petal. Wanted to know how far back I’d known them. Most my entire life. Way before Peg became a war widow. I told him things were troubled between the two of us. Since the flood. That’s when he asked if I thought Petal was beautiful. There’s no denying her beauty. Yet I don’t care for it nearly so much as watching his pale backside move up the bank, all the way to the train tracks. We sidestep along the bridge and balance ourselves, toes tipping the edge. Up here the night is thick with gnats. We swipe them away. In truth I’ve been afraid of water since the flood washed my mother away. Yet being beside Jimmy Smart makes me feel untethered from before. It’s why I’m here instead of staying away like I’d planned to. Then he wants to know if I’m set. I nod. And we leap into the night. The feeling of falling rushes over my skin lasting the longest time. Before disappearing beneath the wet, ink black and everywhere. Kicking against the cold until I’m above the surface. Hearing Jimmy Smart whoop. Him shaking the river from his hair. We hang there in the water while a freight train rolls across the track, moving sand that someday will be the windowpanes people look out of. He tells me he’s cooled off now. I follow behind onto the riverbank, the grass sharp beneath my feet. No breeze at all. Using our underdrawers we wipe the wet from our skin. Pull on trousers. Shirts left unbuttoned. Lastly our boots. Jimmy Smart lights two Woodbines, passes me the spare. When he asks about the field, how exactly is it cursed, I open my mouth but no sound comes out. I wish I could tell him the truth. I know what Dreama would say—if wishes were horses. He looks at me for a time, his eyes like two pieces of shiny black flint I can see myself in.

Go ahead and ask me. Cuz I can see you’ve something on your mind, Jimmy Smart says.

How’d you know—’bout the curse? I say.

Petal told me the field’s no good.

She’s right.

Looks fine to me. Like the flood water went around it.

Some things are not—what they seem.

Those broken windowpanes have anything to do with it? Cuz if I catch the bastard hurling stones he’ll be sorry.

The stones started—after the flood.

If you’re right about the curse, I know a fortune teller who might know how to rid you and your aunt of it. Name’s Esme. She’s not blood or nothing. Closest thing I have mind. And she knows things no one else can.

Like what?

I don’t know. If it’ll rain tomorrow.

Will it?

You’d have to ask her.

She tell you—your future?

Don’t need no one to tell me that, Jimmy Smart says.

Me neither, I say.

Dreama has gone to church. I won’t believe there’s anything inside those walls that’ll ease her. Not the Reverend, who is a liar. Not Jesus, hanging nearly naked tormenting me. All church brings is more trouble. Her returning home with an armload of remnants the flood left behind. Strewn beside fields where crops can’t grow now the dirt’s ruined. Mismatched shoes. A child’s doll. Half a plate, crescent-shaped and more blue than white. And cabinet photographs of stiff people who appear conjured from another time. Yet it’s more. I’m mad at Dreama and God and Jimmy Smart for stirring something inside I haven’t any name for. Mostly I’m mad at myself. Desire is cunning like that. While I patch our windowpane with greaseproof paper I can see him through the hole. Standing idle. He’s handsome in the same way Petal and Dreama are beautiful. My mother too. These women who make men ache after them. I press my left eye against the glass and squint through the hole. Like being fourteen years old at the seashore when I held on to the coin-operated telescope. Inside the circle a gang of five men were fooling around. Their skin tan. Hair glinting in bright sunlight. But blackness came as my money ran out, and I’d been left with nothing but big white gulls overhead swooping and calling huoh-huoh-huoh. Ladybirds that crawled up and down my arms no matter how hard I brushed them away. A red-faced man on the platform told us they blew in the day before. Thousands of them. Until the sand was plagued with their black and red backs. Dreama told me it meant trouble’s coming. I nodded because it was too sweltering to be disagreeable. And the picnic bag heavy to haul across the shoreline, until we found a stretch of sand near the swell with hardly any stones. The waves roared, their tips like torn paper, before they rushed up and soaked away. Unbuttoning my shirt, I told Dreama and my mother I was going in. The water, more green than blue, grew colder the further I waded. Until I was alongside the herd of men from the telescope. Only they were older up close. Skin pock-marked out from behind sand-worn glass. Still they stirred me. I ducked beneath the wet and when I surfaced they’d moved further away. Turned back and laughed at me. I wished a whale would swallow them. And swam back to shore. There I’d ate warm sandwiches with my mother and Dreama. Until restlessness pulled me down the beach, towards the cliffs, coloured red as rust. Beside a rockpool where sticklebacks darted about, I reached in my hand and disturbed them. Unaware I’d been followed. Until his shadow turned the water stormy. He was one of the men from before. A gap between his front teeth. His swimming trunks bright blue, except for the ladybirds. Though he didn’t utter a word, I knew he wanted me to go with him. I trailed behind. Watched muscles move beneath summer skin. At the foot of the cliff he disappeared. Behind a fallen rock, high as our heads, I found him with his swimming trunks heaped at his ankles. While he’d tugged his dick, straightening the kink. My own dick had been rigid since the rockpool. He put his palms either side my head and lowered me down. Then my nose was busy with the smell of him. And the taste. Green water, piss and semen. Afterwards, he tied the cord of his swimming trunks, double knotted. Walked away. I leant back against the rock, cool where the sun couldn’t reach, and cried. Never caught his name. Because he didn’t throw it. Though I called him Cliff.

How long you gonna stare out that window? Jimmy Smart says.

You—startled me, I say.

Didn’t mean to. Door was open. Here, you left your wet underdrawers behind.

Sorry—

What you thinking about?

Ladybirds—

All right. Now I’m here, you mind if I have a glass of water?

Glasses are—up on the shelf.

Sweltering out there.

Here too.

I’ve not seen your Aunt Dreama. She all right?

She’s gone to church.

Was wondering if you wanna come with me later.

Where to?

The station. Cuz I’m having a big burn up. Been hauling wood these past two days.

Might be—too warm for it, I say.

Guess it is. But it needs doing anyway, Jimmy Smart says.

Train tracks stretch into the distance, the same rusted colour as the stone station, stitching together the line between ground and sky until it’s beyond blurred. The air is thick with the scent of cut wood, stirring me. Trailing behind Jimmy Smart, I have my hands pushed deep in my trouser pockets. We move past the station towards the treeline, where the indigo woodland watches us. I dislike these trees. Their branches shifting with the weight of murk and shadow. Relief comes halfway between here and there, where Jimmy Smart has hauled a big pile of wood, higher than our heads, and as wide. He’s ripped down the entire fence that one time ran along the platform. The wood, once whitewashed and proud, is more grey than not after the flood. Over to the side there’s three rusty oil drums in a crescent. And I feel the sting of disappointment as Petal drifts our way, wrapped in a dark lace shawl that could be a scatter of blackbirds. She is beautiful in half-light. Jimmy Smart is all big-grinned introductions. Petal reminds him she has known me most her entire life. Since we played beneath the iron bridge. Swam naked in green water. I dip my head. As though suddenly the dirt itself has said something interesting. Because me and Petal are not playmates anymore. We’ve hardly had two words to utter to one another since the flood. Since that night at Lynn Boxing Gym with Shane Wright and Bill Bredlau, when the storm threatened the four of us. Watching her now, curious eyes travelling the showman from dusty boots to unkempt hair, I don’t hate her as I did before. Though that night swims around my head like a goldfish in a bowl, until Jimmy Smart banishes the gloom with the first flicker of fire. Rubs his palms against the backside of his trousers to clean away the muck. Petal complains about the gnats, worried they’ll eat her alive. Yet the smoke from the bonfire will drive them far. For a time we sit on our drums watching the light. Every once in a while my knee knocks Jimmy Smart’s. Who drinks from a bottle he passes around, made with wild things. Herbs gathered by a woman called Esme. I’m unable to fathom these plants, where they sprang from. My face feels flushed from the heat. When Petal starts humming, Jimmy Smart gets up off his drum. His eyes are full. Bright as his shirt. He shivers like something unseen has taken hold. Begins at his boots and travels upwards to his crown where his hair glows amber. The fire snaps and chucks sparks all over the place, as if he’s conjured the brightness himself. He sways and hops and whirls. Petal is keeping time, the palm of her hand a steady beat against her thigh. Jimmy Smart’s feet stir dust clouds, while his arms make pleasing shapes across the night, arches from here to there. Though I can’t be certain where there is. Or why he’d want to cross this distance. Then Petal is on her feet moving around the fire after him. Her pretty voice haunting the night. But it’s Jimmy Smart that has me mesmerised. When he dances it’s like watching fire burn beneath his skin, bones for kindling. Doesn’t matter that I can’t see the bright blaze blistering. I just know it burns. Might be Jimmy Smart talks to the fire. Or the drink turning his head. Alcohol is clever like that. He pulls me to my feet, where we go around and around trailing Petal. Jimmy Smart holding loosely onto my hand.

How about that fire. Was something else all right? Jimmy Smart says.

It was— I say.

Petal’s something else too. Peg’s worried I’ll corrupt her. Like I can’t stand to be around a girl without—

What?

It doesn’t matter.

Does to me—

People are smallminded. I reckon it’s why I’m out in black barn. Forget about it.

If you want.

I do—

Where’d you learn to—dance?

Esme taught me. Her keen on such foolish things.

I—liked it.

About before. I didn’t mean anything by it, Jimmy Smart says.

Good night— I say.

I am restless. Desire is cunning like that. Can feel it in the cotton sheet beneath my back, damp from the sweltering night. My feet swing back and forth. Heels grazing floorboards sound like a rasp smoothing uneven wood. If I stretch a little further I’ll be able to unsettle the pile of stones at the foot of my bed. Scatter them across the floor, where the clatter can rouse the night outside. Tell the field I’m coming. Though the noise might wake Dreama. Before, she had come home from church carrying a teacup shaped like a seashell. For near an hour she’d sat at the kitchen table, smoking her Woodbines, mesmerised by the china, so fine light from the window passed right through. Held it to her ear. Until I told her of the bonfire with Jimmy Smart. Where she wondered what sort of lunatic would light a fire in this damn heat. I’d shrugged. Reminded her he’d been hauling rotten wood for days. Dreama didn’t speak another word. Least not with her mouth. Yet her face, even the way her lean fingers brushed against that pretty teacup, told me she’d seen one of her signs. Clear as anything. Same way in the black windowpane lit by lamplight, I can see myself right now. Curious how my middle is missing where the window is wedged open. How my hair, parted too neatly, is shiny as boot polish. I can still feel Jimmy Smart’s warm hand on the nape of my neck, where he’d placed it after we’d quit whirling around the fire. Dizzy from spinning around and around. Him communing with the flames and all. Breathless, he’d tugged me towards him. His gaze more mysterious beneath moonlight. As though he might tip his head and howl. Instead, with a wink he glanced back at Petal, who’d stood still as the iron bridge out at the river. Then Jimmy Smart kissed me hard. I tasted cigarettes and drink and something else I don’t know the name of. A puzzle. Making me hungry for more in this heat. More of him. I get up and grip the wooden window frame. The paint peeling in a pattern that reminds me of a grass snake that’s shed its skin. But the window won’t budge another inch. That’s when I see him standing there. Jimmy Smart. Leaning against black barn in such a way as to invite me out into the hot night. He’s shirtless. I’m in two minds if I should go to him, even though the field is calling. But the part of me that is neither mind has already pulled on trousers. Slipped a vest over my head. Like my skin, the cotton has held on to woodsmoke. I let my tongue travel across my dry lips. Though he’s left no trace of himself there. And head outside.

Can’t sleep either? Jimmy Smart says.

Not so much, I say.

Where you going?

To lie down—in the field.

You and Dreama sure are an odd pair. Coming here to this field the way you do. All times of day and night.

Might say—the same about you.

How’d you mean?

Was odd of you to—kiss me.

Told you already, it didn’t mean anything. I did it to make Petal mad. She’s so full of herself is all.

She’ll be trouble now.

Who cares.

You not worried—she’ll tell Peg?

Tell her what?

That you’re—like me, I say.

I ain’t, so it doesn’t matter, Jimmy Smart says.