Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

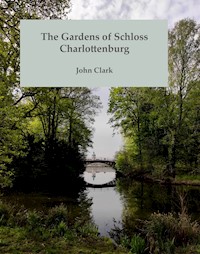

With a 'place by place' description of the gardens of Schloss Charlottenburg in Berlin and an introduction to their history, this profusely illustrated e-book in english is intended to enhance visitors understanding of the place they've visited and is for anyone with an interest in gardening and garden history. From their beginnings as the gardens of a country house at the end of the seventeenth century, they are now a compact, yet very diverse haven in the heart of the modern city.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 121

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE GARDENS OF SCHLOSS CHARLOTTENBURG

An Illustrated Introduction

by

John Clark

INTRODUCTION

A stroll through the gardens of Schloss Charlottenburg leads the visitor through the formal baroque parterre, past the single jet of its fountain, with a rainbow if you‘re lucky, towards a cast iron balustrade flanked by peculiar putti, where a few steps lead down to the waters-edge of a large pond surrounded by paths and trees with a distinctively arched red bridge at the far end and beyond that, an obelisk set among grassy meadow and woodland with the elegant pale blue Belvedere near the river.

With the left bank of the River Spree to one side and woodland on the other where an avenue of sombre conifers leads to a Mausoleum, the park is surprisingly compact, about half a square kilometer in area (53hectares), or a fifth of a square mile (circa 130acres), about double that of the Jardin de Luxembourg in Paris, but less than Regent‘s Park in London, which is itself much smaller than New York‘s Central Park.

Each area embodies a different approach to landscape and gardening, in a pattern established over three hundred years since the Schloss was originally built in the final decade of the seventeenth century as the private residence of Duchess Sophie Charlotte, wife to Friedrich, Elector of Brandenburg, who were soon after crowned King and Queen in Prussia at a ceremony in Königsberg.

The gardens were developed in two long phases, firstly between 1695 and 1780 as a formal Baroque garden with parterre, carp pond, sports pitches and bosketts, then after 1780 the gardens were comprehensively remodelled after the English style of landscape gardening with several new buildings to create a layout that prevailed for over a century after the Mausoleum was built.

However, these impressions are deceptive. The Schloss was severely damaged during World War 2 and might have been demolished to make way for a municipal park, but for the determination of art historian Margarete Kühn and her colleagues who lobbied successfully for its reconstruction and for restoring the grounds as a Historic Garden, an ambitious project, which has become a continuing process of remodelling and restoration.

The 18th century Formal Baroque Gardens 1695-1780 - A view of proposals by architect Johann Friedrich Eosander in 1710, published in the Theatrum Europaeum.

The Landscaped Gardens 1780-1950 - a view from 1856.

The contemporary recreation as a ‘Historic Garden’ - 1950’s onward.

In the second half of the twentieth century, the gardens underwent many changes. The High Bridge (Hohe Brücke) was painted red for the first time in 1962 and ‘Red Bridge’ became the name the locals use. The impressive Parterre is a recreation with similarities to plans from 1740. Almost three hundred years after first being proposed, a powerful fountain has finally been installed.

The obelisk is a piece of contemporary conceptual art from 1979 and the fanciful group of grotesque putti by the Carp Pond were designed and fashioned in the early 1980’s. There are probably fewer statues in the Schlossgarten now, than at any time in its history.

The contemporary Schlossgarten is a highly successful modern pastiche, an unusual achievement of ‘might have been authenticity’ and a ‘potpourri’ of layouts and garden furniture that brings its own challenges for the gardeners to handle, facing the problems of climate change and the crisis of biodiversity epitomised by the collapse of insect popula-tions, all within the remit of sustaining a historic garden in a modern setting.

With over a million visitors a year, the gardens are used by more people than ever before, while following, at least to some degree, plans proposed by gardeners in the seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. A major change in the autumn of 2022 has been the reopening of the old theatre building as a Museum dedicated to the remarkable Berlin artist Käthe Kollwitz, a welcome shift of cultural emphasis, as the influence of the Prussian monarchy recedes into the murky shadows of European history. A more fundamental change is the improvement in air quality since the closure of the nearby airport at Tegel.

This book is intended to give visitors, in particular those with an interest in gardens and gardening, an aide memoire to the place they have seen and as a set of notes to myself providing some kind of perspective into the Schlossgarten as a place that has changed and continues to change with unexpected rapidity, hopefully providing a key to understanding the significance of each of the three major phases of development, baroque, landscaping and ‘historic garden’, and their contribution to the condition of the gardens as they are now.

Inevitably, visitors gain completely different impressions depending on the time of year and the passage of the seasons, so the photographs have been selected to reflect those contrasts.

Trees grow, storms blow, dogs and people come and go.

SCHLOSSGARTEN CHARLOTTENBURG

PLAN - 2023

KEY

BUILDINGS

1. Schloss 2. Orangery (Old) 3. Small Orangery (New)

4. New Pavilion 5. Mausoleum 6. Belvedere

GARDEN FEATURES

Luisenplatz- A

Courtyard - B

Orangery - C

Terrace - D

Parterre - E

East and West Bosketts - F

Carp Pond - G

Luiseninsel- H

White Mound aka Elswald - K

Trümmerberg- M

Pheasant Garden- N

Fürstenbrunner Graben - FG

Red Bridge(Hohe brücke) - RB

Fieldway Bridge(Feldwegbrücke)- FB

Schloßstraße- STR

A view of the Carp Pond and Schloss from the Red Bridge.

Rime frost on trees and the Red Bridge in 2013.

Parterre and Schloss from the garden side.

PART 1

IN THE BEGINNING 1695-1705

In July 1699, thirty-one year old Duchess Sophie Charlotte, held a birthday party for her husband, Friedrich, Elector of Brandenburg to inaugurate the recently completed Schloss and Gardens that would eventually bear her name as Schloss Charlottenburg. Friedrich had acquired the land for her to build her own summer residence on the banks of the River Spree almost exactly midway between Berlin and Spandau, set in open countryside among fields and woodland near the village of Lietze, later Lützow, where the Berlin-Spandau road came close to the river, so the Schloss could be reached either by boat or by carriage within an hour, a symbolic distance - 1 Prussian Mile - some 5 English miles. Her previous residence, the Schloss Caputh, south of Potsdam, had been much further away and far more difficult to reach from Berlin.

He was fonder of her than she of him and they agreed a pragmatic arrangement that he would only visit her by written invitation, hence the birthday party was a courtesy of a sort and a statement underlining her independence and status as daughter of the influential Elector of Hanover. The new Schloss, known originally as Schloss Lietzenburg, bore a marked similarity to her parents’ plans for their own summer residence at Schloss Herrenhausen in Hanover, which was being built at the same time, but with much larger formal gardens. There were precedents in France at chateaux like Sceaux for the parterre, Marly-le-Roi for lakes and above all Versailles for grandeur.

In the beginning, the Schloss was as much a fine country house, as a grandiose Palace.

Sophie Charlotte was well acquainted with the French court and fashions for architecture, having been to Paris as part of her upbringing and the influence of André le Nôtre who designed the gardens in Versailles had become ubiquitous, so it was no surprise that another French gardener, Simon Godeau should be appointed to create the Schlossgarten, when the landscaping and planting began in 1696, taking over from the Dutch engineers who had worked for decades on land improvement and canals in Berlin.

The building Sophie Charlotte would have known would probably have been no wider than the span of the tiled roofs, four sets of windows either side of the central oval salon and without the tower, which would be completed several years later.

She enjoyed a small private garden close to the building and at her instigation, as at Marly-le-Roi, the windows of the main rooms of the Schloss were constructed to be opened at ground level so it was easy to step directly into the gardens, whose original layout followed a series of sight lines defined by the views from the large Oval salon towards Spandau, Tegel and other regal residences in the region. Her decision to live on the ground floor was unusual, giving the gardens a personal ambience. At first there weren’t even stairs to the upper floor. From the outset, the Schloss and Schlossgarten made an intimate ensemble.

By the spring of 1698, Sophie Charlotte wrote that she could begin to enjoy the gardens and that most of the trees had been planted. These were mainly limes for avenues flanking the parterre and carp pond, with chestnuts, oaks and planes, especially in the bosketts. A year later, in 1699, the parterre, east and west bosketts and paths around the Carp Pond were well on their way to completion.

While the gardens were less extensive than the most ambitious proposals and the house soon revealed itself as too small for retinue and servants, the creation of a Baroque garden with water features was a novel development in Germany. In 1702, Johann Friedrich Eosander, a young court architect was appointed to take over as ‘Baudirektor’ - Director of Works. That year, the opera ‘I Trionfi di Parnasso’ was performed in one of the two berceaux. But this first flourish of life at the Schloss flowered only briefly, with music performed in the gardens as Sophie Charlotte enjoyed a variety of guests and regular visitors including the polymath Leibniz, John Toland an Irish freethinker and resident composers Attilio Ariosti and Giovanni Bononcini. She is remembered as a cultivated woman and for having promoted the establishment of the Prussian Academy of Science with Leibniz as its first President.

That all came to an end with her untimely death in 1705 at the age of 37.

Trellaced pyramid at one corner of the Parterre.

Schloss Charlottenburg from the garden side as envisaged by Eosander - engraved by Martin Engelbrechtand published in the Theatrum Europaeum in 1717 by the Merian Verlag, Frankfurt.

(c) Deutsches Historisches Museum.

THE BAROQUE GARDEN 1705-1780

Sophie Charlotte‘s widowed husband, by now Friedrich I, King in Prussia, renamed the Schloss and surrounding district in her memory as Charlottenburg and Eosander undertook a wave of new work on both buildings and gardens taking the gardens some way towards his proposals illustrated in the Theatrum Europeaum in 1717 most notably the Orangery. Godeau had to amend his painstakingly defined sightlines to accomodate the Orangery and several pagoda style fishing huts were built as focal points.

The general notion of the Baroque garden was to create an imposing impression from the main building and terrace looking over the highly decorative parterre framed by avenues of trees and woodland with bosketts for all kinds of purposes.

An innovative novelty in the seventeenth century, indeed an expensive luxury as they cost a great deal to create, such gardens needed a huge amount of labour to maintain, as they still do. Conceived as a pleasure garden, rather than following the expectations that a garden is there to provide fruit and vegetables, or a supply of flowers, herbs and medicinal plants, which were more familiar notions to northern Europeans, this was a profound change, civilising the agrarian landscape. Nevertheless, grand country houses did still need produce of all kinds and the kitchen gardens in the Schloßstraße became a serious commitment as exotic delicacies like figs, bananas, melons and pineapples were raised alongside more mundane fruit like apples and pears being grown ‘out of season’, while freshly cut flowers were required for the house.

Detailed descriptions of the Baroque style were to be found in the Treatese on Gardening by Jacques Boyceau de la Barauderie published in 1638 and regularly reprinted until 1707, or the Theory and Practice of Gardening by Désallier d‘Argenville published in 1709, then reprinted and translated over the next half century. These recommendations imply a subtle stylistic etiquette that informed visitors could recognise and appreciate as an act of connoisseurship.

Parterre de broderie in summer.

Parterre de broderie in winter.

Such gardens are not for everyman, but conceived, as Boyceau proposed, ‘for Princes, Aristocrats and Wealthy Gentlemen of Means’. Successive generations of gardeners and landowners alike had access to handbooks on good horticulture and garden design in the formal French style.

In 1713, Désallier d‘Argenville was to write that gardening should pursue 4 main goals, firstly to promote Nature‘s artistry; then to avoid excessive gloom and shadow, thirdly neither to obscure, or reveal too much at first sight, and fourthly to create the impression that the garden is more substantial than it is - priorities that seem as credible today as they were when he wrote them.

The terminology for different areas of Baroque gardens, such as parterre and boskett, or bosquet, were well understood among gardeners, architects and landowners and these terms are still used for parts of the Schlossgarten.

Among the earliest to provide a clear stylistic definition was the architect Augustin Charles d‘Aviler (1653-1701) whose resumé was distinguished by his having designed a Mosque in Tunis after being enslaved by pirates before taking up his studies in Rome. He eventually worked in Montpelier and published a Cours d‘Architecture.

The Parterre was regarded as the jewel of the garden, according to d‘Aviler, who wrote that the large area of levelled ground should be as broad as the main building itself. The carefully prepared area is divided into plots by paths.

Lines of low box hedges, about a foot high, neatly trimmed and squared off, create an embroidered patterned, a parterre de broderie, embellished by contrasting coloured sands or chippings, surrounded by colourful beds of flowers and shrubs, so floral swirls and lacy figures, or coats of arms and symbols, mirrored symmetrically and broad perspective give the parterre a graphic character of ‘french curves’ when seen from a distance. Other variations might include simple lawns, or patterns created between grass, hedge and flowers. These various plots can be fringed with bedding plants and framed by decorative ornaments, urns and vases, or shrubs in tubs, hence the notion of a border. Topiary adds another set of shapes, with formal geometric figures devised from heavily pruned and regularly clipped and tended shrubs and trees.

The geometries of the parterre bring the added benefit of being able to be enjoyed by someone looking down from windows in the Schloss without having to venture outside, a distinct advantage during the winter.