Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: John Donald

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

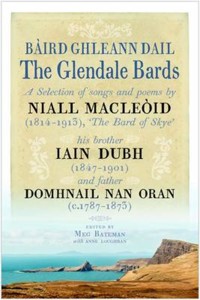

This book marks the centenary of Neil MacLeod's death in 1913 with the republication of some of his work. It also publishes for the first time all of the identifiable work of his brother, Iain Dubh (1847 - 1901), and of their father, Domhnall nan Oran (c.1787 - 1873). Their contrasting styles mark a fascinating period of transition in literary tastes between the 18th and early 20th centuries at a time of profound social upheaval. Neil Macleod left Glendale in Skye to become a tea-merchant in Edinburgh. His songs were prized by his fellow Gaels for their sweetness of sentiment and melody, which placed a balm on the recent wounds of emigration and clearance. They are still very widely known, and Neil's collection Clarsach an Doire was reprinted four times. Professor Derick Thomson rightly described him as 'the example par excellence of the popular poet in Gaelic'. However, many prefer the earthy quality of the work of his less famous brother, Iain Dubh. This book contains 58 poems in all (32 by Neil, 14 by Iain and 22 by Domhnall), with translations, background notes and the melodies where known. Biographies are given of the three poets, while the introduction reflects on the difference in style between them and places each in his literary context. An essay in Gaelic by Professor Norman MacDonald reflects on the social significance of the family in the general Gaelic diaspora.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 451

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

BÀIRD GHLEANN DAIL

THE GLENDALE BARDS

a selection of songs and poems by

Niall MacLeòid (c.1843-1913),

his brother Iain Dubh (1847-1901)

and their father Dòmhnall nan Òran (1787-1872)

edited by Meg Bateman

with Anne Loughran

ISBN: 978-1-907909-22-1

This eBook edition published in 2013 by Birlinn Limited West Newington House Newington Road Edinburgh EH9 1QSwww.birlinn.co.uk

Copyright © Meg Bateman, Anne Loughran and Norman MacDonald, 2013

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 9780859766906 eBook ISBN: 9781907909221

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

CONTENTS

Foreword

Acknowledgements

List of Illustrations

Introduction

Two Poems on Neil MacLeod’s Death

A Note on Editorial and Translation Practice

Biographical Details

Aiste le Tormod Dòmhnallach

NIALL MACLEÒID

Introductory Notes to Songs and Poems by Niall

Homeland

1.

An Gleann san Robh Mi ÒgThe Glen Where I Was Young

2.

Fàilte don Eilean SgitheanachHail to the Isle of Skye

3.

Cumha Eilean a’ CheòLament for the Isle of Skye

Love

4.

Màiri Bhaile ChròMary of Baile Chrò

5.

Duanag an t-SeòladairThe Sailor’s Song

6.

Mo Dhòmhnallan FhèinDear Donald, My Own

7.

Mo LeannanMy Sweetheart

Gaelic

8.

Am Faigh a’ Ghàidhlig Bàs?Will Gaelic Die?

9.

Brosnachadh na GàidhligAn Incitement to Gaelic

Historical Comment

10.

Còmhradh eadar Òganach agus OiseanA Conversation Between A Young Man And Ossian

11.

Sealladh air OiseanA Sight Of Ossian

12.

Mhuinntir a’ Ghlinne seoPeople Of This Glen

Protest

13.

Na Croitearan SgitheanachThe Crofters Of Skye

14.

’S e Nis an t-ÀmNow Is The Time

Religious and Didactic

15.

Taigh a’ MhisgeirThe Drunkard’s House

16.

An UaighThe Grave

Humorous

17.

Òran na Seana-MhaighdinnSong of the Old Maid

18.

Turas Dhòmhnaill do GhlaschuDonald’s Trip to Glasgow

19.

An Seann FhleasgachThe Batchelor

Emotional Set Pieces

20.

Bàs Leanaibh na BantraichThe Death of the Widow’s Child

21.

Cumha LeannainLament for a Sweetheart

22.

Mi Fhìn is AnnaMyself and Anna

Occasional

23.

Cuairt do Chuithraing

A Trip to the Quiraing

24.

Coinneamh Bhliadhnail Clann Eilean a’ CheòThe Skye Annual Gathering

25.

Fàilte don BhàrdWelcome to ‘Am Bàrd’

Village Verse

26.

Dùghall na SròineDougall of the Nose

27.

Tobar Thalamh-TollThe Well of Earth Hole

28.

Dòmhnall Cruaidh agus an CeàrdTough Donald and the Tinker

Nature

29.

Rainn do NeòineanVerses to a Daisy

30.

Ri Taobh na TràighBeside the Shore

Elegy

31.

Don Lèigh MacGilleMhoire, nach MaireannTo the Late Dr Morrison

32.

John Stuart BlackieJohn Stuart Blackie

IAIN DUBH

Introductory Notes to Songs and Poems by Iain Dubh

Sea-Faring and Homesickness

33.

Gillean Ghleann DailThe Boys of Glendale

34.

Mo Mhàthair an ÀirnicreapMy Mother in Àirnicreap

35.

’S Truagh nach Mise bha Thall an CealabostA Pity I Wasn’t Over in Colbost

Love

36.

Anna NicLeòidAnna MacLeod

37.

Ò Anna, na Bi Brònach

Oh Anna, don’t be Troubled

Satire and Social Comment

38.

Aoir Dhòmhnaill GhranndaThe Satire of Donald Grant

39.

Òran Catrìona GhranndaA Song for Catriona Grant

40.

Nuair Rinn Mi Do PhòsadhWhen I Married You

41.

A’ Bhean Agam FhìnMy Own Wife

Praise

42.

Òran an Àigich The Song of the ‘Stallion’

43.

Òran a’ CheannaicheThe Song of the ‘Merchant’

44.

Òran do dh’Fhear HùsabostA Song to the Laird of Husabost

Occasional Verse

45.

An Gamhainn a Tha aig Mo MhàthairThe Heifer My Mother Has

46.

Tost Dhòmhnaill an FhèilidhA Toast to Donald of the Kilt

47.

An Eaglais a Th’ ann an Lìt’The Church that’s in Leith

48.

Don Doctair GranntTo Dr Grant

DÒMHNALL NAN ÒRAN

Introductory Notes to Songs and Poems by Dòmhnall Nan Òran

Clan and Praise Poetry

49.

Marbhrann do Chaiptean Alastair MacLeòid ann a’ BhatainElegy for Captain MacLeod in Vatten

50.

Smeòrach nan LeòdachThe Thrush of Clan MacLeod

Love

51.

Litir Ghaoil ga FreagairtA Love Letter Answering Her

Satire and Social Comment

52.

Òran Mhurchaidh BhigMurdo Beag’s Song

53.

Rann Molaidh do Sheann BhàtaA Verse in Praise of an Old Boat

54.

Rann Fìrinn don Bhàta CheudnaA Truthful Verse to the Same Boat

55.

Rann Molaidh do Thaigh ÙrA Verse Praising a New House

56.

Òran Molaidh a’ BhuntàtaA Song in Praise of the Potato

57.

Rann do dh’Èildearan an Loin MhòirA Poem to the Elders of Lonmore

Religious and Didactic

58.

Dàn a’ BhreitheanaisA Poem on the Judgement

59.

Dàn don GhrèinA Poem to the Sun

Nature

60.

Òran do Thulaich Ghlais ris an Abrar ‘Tungag’A Song to a Green Hillock Called ‘Tungag’

Sources for the Texts and Tunes and Editorial Notes

A Word on Dòmhnall nan Òran’s Metres

A Note on the Editors

Bibliography

Abbreviations

Index of Titles

Index of First Lines

End Notes

Foreword

Ian Blackford of the Glendale Trust proposed re-editing and translating Neil MacLeod’s Clàrsach an Doire to mark the centenary of Neil’s death in 1913. Hugh Andrew of Birlinn publishers approached me to carry out the work, but I remembered a suggestion made by my fellow post-graduate student, Anne Loughran, in the 1980s. She maintained that the publication of Neil MacLeod’s poetry, alongside that of his father and brother, Dòmhnall nan Òran and Iain Dubh, would be a laboratory of changing literary tastes revealed within one family. Having researched the sources for such a publication in her MLitt thesis, ‘The Literature of the Island of Skye: A bibliography with extended annotation’ (University of Aberdeen, awarded 1986), Anne proposed the idea to the Scottish Gaelic Texts Society in the mid 1990s. The Society felt unable to take the work on at the time, and it has fallen to me, twenty years later, to bring the work out. This book is founded on Anne’s insightful proposal, bibliography and sourcing of relevant material. She and I have made our selection of texts together and she has provided part of the material for the English biographies of the poets. A longer account of the family in Gaelic has been kindly provided by Norman Macdonald, Portree, who has followed the diaspora of the family to the present day, and whose photos, given to him by Neil MacLeod’s grandson, Norman MacLeod, are also used here.

Meg Bateman Skye 2013

Acknowledgements

I am most grateful to Allan Campbell for giving me versions of Iain Dubh’s songs as noted down by his father, Archie Campbell or Eardsaidh Ruadh (1917-1997) of Colbost, from his own memory and from older people in the neighbourhood. He also identified our sixteenth poem by Iain Dubh as this book went to press. Ailean Dòmhnallach (Am Maighstir Beag) has also supplied me with transcriptions of songs by Iain Dubh, which he collected himself. Christine Primrose, Aonghas Dubh MacNeacail, Kenna Chaimbeul, Allan Campbell and Norman Macdonald have helped me with transcribing Iain Dubh’s songs from sound archives. I am grateful to Rupachitta (or Patricia Robertson) for taking me to places in Glendale connected with the MacLeod family. Mary Beaton (Newton Mearns) and Ann MacDonald (Glasgow) have been most helpful regarding the family’s genealogy. Prof. Colm Ó Baoill’s unpublished editions of some of Dòmhnall nan Òran’s work have been invaluable, as have his help and encouragement throughout the process, and his corrections to the completed text. Rody Gorman has been on hand to answer linguistic questions.

The sound archives, Tobar an Dualchais and Bliadhna nan Òran, add another dimension to the texts presented here, for they let us hear the songs sung by traditional singers. They have also been invaluable in allowing me to locate words and identify the tunes for some of the texts below. I am grateful to both bodies for permission to transcribe words and tunes for this book, and to the relatives of those quoted. I am grateful to Neil Campbell (MacBeat) for transcribing the tunes for Iain Dubh’s songs from the sound archives; to Christine and Alasdair Martin for giving permission to reproduce five of their arrangements of Niall’s songs from Òrain an Eilein; and to Eilidh Scammell and Eilidh NicPhàidein for transcribing these tunes into the computer programme, Sibelius.

I must thank Greg MacThòmais and Cairistìona Cain of the library at Sabhal Mòr for generous and inventive help. Ulrike Hogg of the National Library of Scotland found three letters for me from Neil MacLeod to Alexander MacDonald (Inverness), the latter’s poem on Neil’s death, and the MS of the 16th poem by Iain Dubh. A four month sabbatical from the University of the Highlands and Islands was a great help in completing this project.

List of Illustrations

1.Portrait of Neil MacLeod(from the 1902 edition of Clàrsach an Doire)

2.Neil’s wedding(with permission from his grandson, Norman MacLeod, San Francisco)

3.Neil’s family(with permission from his grandson, Norman MacLeod, San Francisco)

4.An t-Àigeach, see no. 42. ‘Òran an Àigich’(photo by Meg Bateman)

5.Iain Dubh’s grave in Montreal(photo by Norman Macdonald, Portree)

6.Dòmhnall nan Òran’s house in Pollosgan(photo by M. A. MacFarlane)

Cover. A tree in the cemetery at Cille Comhghain, Glendale(photo by Meg Bateman)

INTRODUCTION

Neil MacLeod was born in Glendale in Skye about 1843 and at the age of twenty-two he moved to Edinburgh where he remained till his death in 1913. A rare opportunity for examining the influence of life in the Lowlands on his work is afforded by his father and brother also being poets, who remained culturally attached to Skye. Anne Loughran first suggested making this comparison between Dòmhnall, who was born in the 18th century, and his sons, Niall, the Edinburgh tea-merchant, and Iain, the sailor, who some have rated more highly than his famous brother.i The point was reiterated recently by Màrtainn Dòmhnallach in a newspaper article discussing the erection of a headstone for Niall in the centenary of his death in Morningside Cemetery in Edinburgh.ii Changes in poetic taste are clear in the work of the three poets in the same family, spread over two generations and three centuries, with their different lifestyles, urban, rural and maritime. The requirement to produce songs for the Gaelic diaspora in Lowland cities made for a different sort of song from those produced to entertain or edify a Highland community.iii

No other Gaelic poet has suffered such a dramatic change in reputation as Neil MacLeod. Nowadays many consider him facile and superficial.iv Derick Thomson and Dòmhnall Meek have compared him unfavourably with Màiri Mhòr, criticising him for a softness of focus and lack of political engagement with the Clearances and Land wars. While Màiri Mhòr shared a platform with politicians such as Sir Fraser MacIntosh, Niall spoke in generalities from a distance. While Màiri Mhòr’s poetry is passionate and gutsy, Niall is criticised for the simulation of emotion with little heightening of language.v Yet in 1892 Dr MacDiarmid wrote, ‘Niall is probably the best known and most popular poet living’,vi and John N. MacLeod, addressing the Gaelic Society of Inverness in 1917, described Niall’s collection, Clàrsach an Doire, as co-chruinneachadh cho binn blasda tomadach ’s a chaidh riamh an clò (as sweet, pungent and weighty a collection as had ever been printed).vii At the time of his death in 1913, Donald MacKinnon, professor of Celtic at Edinburgh University, referred to Niall as one of the three foremost Gaelic writers of his time:

Since Duncan McIntyre died, no Gaelic poet took such firm hold of the imagination of the Highlanders as Neil MacLeod was able to do… There is a happy selection of subject. The treatment is simple, unaffected. You have on every page evidence of the equable temper and gentle disposition of the author – gay humour or melting pathos; happy diction; pure idiom; exquisite rhyme… and the melody of versification.viii

Derick Thomson writes, ‘Niall Macleòìd would seem to be the example par excellence of the popular poet in Gaelic, and he more than any other became part of the pop culture of his time’.ix It may be easier to try to account for Niall’s popularity in his own time than to give a conclusive assessment of the worth of his poetry.

The social conditions which Niall encountered in the Lowlands were very different from those of the ceilidh house in the townships of the Highlands. For the first time Gaelic speakers from all over the Highlands were meeting socially at dances in the cities of the Lowlands. While traditional songs had alluded to specific communities and places, a new sort of song was required for the Lowland gatherings that would evoke a common background and identity through some sort of generic neighbourhood and landscape. The new urbanisation of the Gaels made new demands on their poets: pieces were required for the annual gatherings of Gaelic societies, and after 1893 for singing at the Mod, for encouraging the Gaelic language, and for historical pieces, arising from a new self-consciousness about being a Gael.x

While the characters and places of Niall’s father’s and brother’s songs were known to the people of Glendale, in Niall’s songs, characters and place become every community and every place. This accounts in large measure for the vagueness of Niall’s verse, so different from the traditional exactitude of Gaelic verse.xi His songs were required to entertain, to be easily memorable and immediately understandable, without the length, complexity of argument or of vocabulary, or the specificity of emotion seen in the work of his father and brother and other traditional poets. It has been suggested that the different subjects of his love songs – Sìne Chaluim Bhàin, Màiri Bhaile Chrò and Màiri Ailein – were one and the same girl.xii

Niall’s father, Dòmhnall nan Òran, was born in 1787, his life therefore overlapping with Uilleam Ros’s and Dùghall Bochanan’s, while Mac Mhaighstir Alasdair and Donnchadh Bàn were only a couple of generations older. He escaped the press-gang by working as a road-tax collector which took him all over Skye. Like Robert Burns and Alexander Carmichael, his work allowed him to collect poetry and stories. Some of these he published with his own poetry in Orain Nuadh Ghaelach in 1811, with the financial help of four MacLeod tacksmen.xiii He emigrated to America, perhaps as a result of the death of his sweetheart at the age of twenty-one and his boredom with fishing as a livelihood, but returned fifteen years later. In 1839 when he was fifty-two he married Anna MacSween of Glendale and they had a family of ten. He published another book at the end of his life in 1871, but we are to understand from mention of mss in the possession of his widow that a lot more of his work has been lost.

Dòmhnall is a traditional poet: he acts as a clan poet in praising the chief and in evoking a bird, in the traditional manner, to recount the past glories of the clan.xiv He uses satire as a means of social control, sometimes to mock but sometimes to marshal righteousness to correct wrong-doing (see nos. 52-57). He is highly literary and moves easily between genres, whether comic village verse, praise, satire, love, nature or religious verse. Sometimes he composes to entertain, but equally he composes to caution and exhort (see nos. 58-59). Most of his poetry is passionate and personal with a range of metre, diction and vocabulary.

Niall was the oldest surviving child of Dòmhnall’s and Anna’s children. He moved to Edinburgh in the 1860s to join the tea firm of his cousin Roderick MacLeod, for whom he worked as a travelling salesman. In 1889 he married Katie Bane Stewart, a schoolteacher and daughter of a schoolteacher of Kensaleyre, Skye,xv and they settled and raised a family at 51 Montpelier Park in Bruntsfield, Edinburgh.

MacKinnon spoke of Niall’s ‘equable temper and gentle disposition’, and it seems he was different from his father and his brother, both in outlook and personality. However, an early poem of Neil’s, no. 10 ‘Còmhradh eadar Òganach agus Oisean’, composed when he was twenty-eight and left unpublished in his lifetime, demonstrates a forcefulness and anger rarely seen in his later work:

Tha na Gàidheil air claonadh om maise

Is air aomadh gu laigse ann am mòran:

Thug iad riaghladh an dùthcha ’s am fearainn

Do shluagh do nach buineadh a’ chòir sin…

The Gaels have declined in their fineness

and have yielded to weakness in many matters:

the rule of their land and country

they have handed to a people with no right there…

Iain Dubh was Niall’s younger brother by three years, and unlike his father and brother, he never published his poems. The contradistinctions between the two brothers may have been exaggerated in local folklore. He was married twice and spent much time away from home as a seaman. In Glendale it was said that he was dubh air a h-uile dòigh (black in every way), in hair, skin colour and even in deed. This last comment probably relates to his skills as a conjuror and powers of hypnosis which would be demonised by the church, but all evidence is that he was a kindly man whose poetry John MacInnes describes as ‘strong, realistic, compassionate’.xvi We know of only fifteen poems by Iain, but it is widely held that Niall saved some for posterity by publishing them under his own name in Clàrsach an Doire. Ailean Dòmhnallach (former headmaster of Staffin primary school) can be seen making the case for ‘A’ Bhean Agam Fhìn’ being Iain’s on You-tube,xvii and certainly its irreverent humour is unlike Niall’s. The people of Glendale generally understood this poem to have been Iain’s, and were critical that Niall had published perhaps three poems of Iain’s without acknowledgement. The present editor suggests on stylistic grounds that the other two may be no. 18. ‘Turas Dhòmhnaill do Ghlaschu’ and no. 23. ‘Cuairt do Chuithraing’.xviii Both exemplify vivid idiosyncratic imagery and celebrate the world of drink so typical of Iain. Their length, though not the metre, is more like Iain, while Niall’s work tends to be shorter. The beguilement of a man by a pretty girl is a theme Iain returns to on several occasions, in ‘A’ Bhean Agam Fhìn’, ‘Nuair a Rinn mi Do Phòsadh’ and ‘Gillean Ghleanndail’ and it is also the moral of ‘Turas Dhòmhnaill do Ghlaschu’.

We cannot know how many of Iain’s songs have been lost. Though Iain does not have the same range of diction in what survives as his father, he likewise composes from his own experience, describing his life at sea and on land, the landscape of Glendale and situations that arose in his neighbourhood in Duirinish and in the cities. He does not show the same moral seriousness as his father, but still praises the praiseworthy (see nos. 42-44) and teases the misguided (see nos. 38-41).

A sense of the difference in tone between the three poets can be shown in excerpts from poems each made on the subject of sea-faring: ‘Rann Fìrinn do Sheann Bhàta’ (A Verse In Praise Of An Old Boat) by Dòmhnall nan Òran, ‘Gillean Gleanndail’ (The Boys of Glendale) by Iain Dubh, and ‘Duanag an t-Seòladair’ (The Sailor’s Song) by Niall (nos. 5, 33 and 53 respectively). Dòmhnall’s poem purports to be a faithful account of a decrepit ship that he had fulsomely praised in the mock-heroic poem preceding it in his 1811 publication. The boat is compared to a beast and a carcase into which the crew venture at their peril, standing hip-deep in water however fast it is baled out. The planks are badly planed, the nails rusting; she contains nests of slaters and enough grass to feed a cow; her mast is like a piece of charcoal, her sails like wet paper and her ropes like rushes:

Bha i sgallach breac mar dhèile

Air dhroch lochdradh,

Bha sruth dearg o cheann gach tairne

Mar à Chorcar;

Mar a bha mheirg air a cnàmh,

’S a làr ga grodadh,

Bha neid na corrachan-còsag

Na bòird mhosgain.

She was bald and pitted like dealboards

planed badly,

there was a red stream from every rivet

as if from crimson dyestuff;

just as the rust had consumed her

and her floor was rotting,

there were nests of woodlice

in her musty planking.

The poem (rather than song, for we are told that Dòmhnall spoke his workxix) was composed about a real event, concerning a local man. However, a certain amount of inter-textuality is involved, not only with the preceding praise of the old boat, but also with Mac Mhaighstir Alasdair’s sea-faring poem, ‘Birlinn Chlann Raghnaill’, whose language and metrics it echoes, and also with the boat satires in the Book of the Dean of Lismore.xx All this very much declares Dòmhnall nan Òran as an 18th century poet himself, deeply conversant with the older culture.

‘The Boys of Glendale’ is probably Iain Dubh’s best known song. It is said he composed it spontaneously, sitting in Pàdraig MacFhionghain’s shop in Glendale, as a response to questions about life at sea from the local lads. He gives a realistic and frank account of his experiences, of being sworn at by other sailors, of the unpleasantness of the heat, storms, rationing, of burials at sea, and the dangers of women and drink in port. If he had a half of what he had spent on drink, he would sooner be at home in Pollosgan.

Gur iomadh rud a chì thu

Mun till thu far do chuairt,

Gun toir droch lòn do neart asad

’S a’ mhaise bha nad ghruaidh;

Chì thu daoine bàsachadh

Gun bhàigh riutha no truas,

Ach slabhraidh mun sliasaidean

’S an tiodhlacadh sa chuan.xxi

There’s many a thing you’ll witness

before you return from your trip,

bad food will take your strength from you

and the bloom from your cheeks;

you’ll see people dying

shown no tenderness or care,

only chains around their thighs

for their burial at sea.

Niall’s Sailor’s Song is in marked contrast to the other two. It is not written from personal experience, but is a sentimental set-piece on the separation of a sailor and his sweetheart as the boat sails.xxii They part with pain and tears and she gives him a lock of hair to remember her by. While she sleeps in her warm bed, he must climb the masts to rig the sails. Though life is hard at sea, the hope of winning her gives the sailor renewed strength. He asks the wind to convey a message to the girl that should she wait for him, she will gain her reward. The notion that wind can speak is new to Gaelic, coming through English songs, and perhaps ultimately through Macpherson’s Ossian.

An àm dhuinn dealachadh Dimàirt,

Gun fhios an tachair sinn gu bràth,

Gun d’ iarr mi gealladh air mo ghràdh,

’S a làmh gum biodh i fuireach rium.

.....

Ach thusa, ghaoth, tha dol gu tuath,

Thoir leat mo shoraidh seo gum luaidh,

Is innis dhi, ma bhios mi buan,

Nach caill i duais ri fuireach rium.xxiii

When on Tuesday we did part,

not knowing if we’ll meet again,

I asked my love to make a pledge

that she would keep her hand for me.

…..

But you, Oh wind, that travels north,

take my greetings to my love,

and tell her that, if I survive,

she won’t lose out if she waits for me.

Many further comparisons could be made between the poets in songs of love and nature.xxiv Again and again we see Dòmhnall and Iain composing from personal experience for a community of which they were a recognisable part, in the same way that Iain Lom, Donnchadh Bàn or Uilleam Ros are recognisable in their songs. By contrast, Niall addresses a generalised Gaelic audience with poems from which he is largely absent as himself. Rather, he is a ventriloquist, producing songs to express different sorts of people, often as part of an emotional set-piece. He speaks for an emigrant leaving Skye, for a widow burying her only child, and a man burying his sweetheart – neither of his own experience nor closely imagined.xxv Niall is the generic poet, a figure in his own fantasies. In ‘Màiri Bhaile-Chró’ for example, the speaker gets lost in the mist in the heights and meets a girl who offers him a bed for the night in her humble dwelling. He swears his undying love for her, yet there is no expectation of their meeting again. It is an idyll evoked by cows, birdsong, flowers and dew, and should perhaps be read as a fantasy of escapism – even of virginity. As the walled garden was to the European medieval love lyricist, so to the Victorian is the girl by herself in a remote sheiling, yet in reality the sheiling was a place for communal activity. The most palpable part of Niall’s different personae is his nostalgia.

Not only is the poet a generic, so also are the characters who appear in his songs – the old maid and old bachelor, the sailor and the sweetheart, the drunk, the widow burying her only child, the man and his wife, Anna. Of necessity, Niall’s Lowland Gaelic community is largely imagined, except for a few prominent individuals such as John Stuart Blackie, the professor of Greek who raised money for the first chair of Celtic, or Dr Morrison who had a shop in Edinburgh where Gaels were wont to meet. How interesting it would be to get more of a picture of his experiences of 19th century Gaelic communities in the Lowlands. Iain Dubh does it magnificently in no. 46 ‘Tost Dhòmhnaill an Fhèilidh’ (A Toast To Donald Of The Kilt), and less so in no. 47. It is to be found in the periodicals of Caraid nan Gàidheal, and later in the songs of Dòmhnall Ruadh Phàislig (Donald Macintyre, 1889-1964). Apart from a few poems for Highland gatherings, Niall’s main purpose was to provide songs of escapism through evocation of the homeland. He lacked Gaelic models for depicting city life and we should look for English language models for what few urban scenes he does depict, e.g. ‘Taigh a’ Mhisgeir’ (The Drunkard’s House, no. 15) and ‘Dòmhnall Cruaidh agus an Ceàrd’ (Tough Donald And The Tinker, no. 28). We see the influence of Victorian idylls and sentimental verse, the songs of Robert Burns (Niall uses the Scotch Habbie in poems 9, 16 and 28 and sets words to many tunes made popular through Burns’ songs, e.g. nos 4, 14 and 17), Chartist songs and the literature of the Temperance Movement of which Niall was himself a member.xxvi

As his brother, Iain Dubh, spoke of his own experience at sea, it is also he who suffers pangs of homesickness in ‘Mo Mhàthair an Àirnicreap’, he whose shoes are eaten by his mother’s heifer, and he who has to carry home a drunken publican.xxvii To underline his presence in his songs, seven of his fifteen surviving songs include his name to vouch for their truth.xxviii As he is a real personality, so too are the characters who appear in the songs: his wife who worries about his drinking (‘O Anna na bi brònach’); Ruairidh Chaluim Bhàin and Calum Ros who take more than their fair share of ling, crabs, and lobsters (‘Oran A’ Cheannaiche’); Dòmhnall Grannd, whom he satirises for cutting boughs from a tree in the graveyard, (‘Aoir Dhòmhnuill Ghrannda’) and whose sister Catrìona he pretends to mollify in ‘Òran Catriona Ghrannda’. Iain’s songs are quirky, closely observed and risk unusual flights of the imagination. His portrayal of the drunken publican in no. 46 ‘Tost Dhòmhnaill an Fhèilidh’ is a good example:

Ged ghabh mi fhìn air spraoi gun chiall,

Bha d’ ìomhaigh a’ cur eagal orm,

Nuair a laigh thu air a’ charpet sìos

Mar chearc ag iarraidh neadachadh;

Thuit an sgian a bha gad dhìon

Le d’ shliasaid a bhith cho leibideach,

Do dhà dhòrn bheag a-null ’s a-nall

A’ sealltainn dhomh mar bhogsaiginn.

Though I went myself on a senseless spree,

your own appearance frightened me,

when you lay down on the carpet

like a hen wanting to nest;

he knife fell that protected you

as your thighs had grown so shaky,

with your two fists going back and forth

showing me how I ought to box.

If Dòmhnall nan Òran sometimes fulfilled the role of praise poet to MacLeod (in ‘Marbhrann do Chaiptean Alastair MacLeòid, ann a’ Bhattain’ and ‘Smeòrach nan Leòdach’, nos. 49 and 50), he was also a village poet, making poetry to commemorate local events, to entertain, to commend and to chastise. Rob Donn makes an obvious comparison with Dòmhnall from the same century. Dòmhnall’s earliest extant poem, composed, it is said, when he was fifteen, ‘Rann Molaidh do Thaigh Ùr, no 54’, is a satire on an ostentatious house built by one of his father’s friends, whose splendour, the poet suggests, will have the effect of overwhelming the guests and frightening them away.xxix

Much more serious is his satire against the church elders of Lonmore (no. 57) who refused to baptise one of his children on the grounds that he was not himself converted (Chan eil thu iompaichte dhà sin). Dòmhnall vents his anger on what he sees as the pharisaic power of the elders. It was said that he knew most of the Bible by heartxxx and, in an overwhelming array of biblical citations, he gives examples of others who have withheld God’s grace, among them the foolish virgins, Balaam, and the prodigal son’s brother. The elders are named and he says they look as if they have been kissed by death. They should be careful that they do not get caught out by their own judgementalism, like Haman in the book of Esther, who was hanged on the gallows he had built to kill Mordecai. This shows Dòmhnall at the height of moral indignation, with a complexity of allusion and intellectual argument never encountered in the work of his sons.

That Niall deals in generalities while Domhnall and Iain deal in specifics is as true of their handling of people as it is of their handling of place. Niall’s famous song, ‘An Gleann san robh Mi Òg, no. 1’, is a beautiful but generalised place that could evoke the homeland of any Gael in the Highlands. Dòmhnall and Iain are more typical of the tradition in evoking a specific landscape through placenames familiar to a local audience. It is the specific sight of Àirnicreap seen at a distance from his ship that awakens Iain’s longing; and it is playing with the concepts of the strangely named headland, An t-Àigeach (the Stallion), and the stack, An Ceannaiche (the Merchant), that provides the material of a further two songs (see nos 34, 42 and 43).

The humour in Dòmhnall’s and Iain’s poems arises from the situations in which they find themselves, but Niall’s humour is that of the music-hall and its stock characters. John N. MacLeod and Professor MacKinnon, quoted at the beginning of this paper, praise Niall for his delicacy of sentiment and exquisite humour, which, they say, differentiated him from other poets.xxxi By today’s standards, this same humour can sometimes seem in poor taste. The old maid is a figure of fun, desperate for any man, poor, blind or coloured (‘Òran na Seana-Mhaighdinn’, no. 17); while a poor drunk dies from his wounds and a cold after being set upon by a demonic crew of tinkers (‘Dòmhnall Cruaidh agus an Ceàrd’, no. 28).

There are marked formal contrasts between the three poets. Niall produced a standard product – almost two thirds of his poems are between six and nine verses long.xxxii This is considerably shorter than the average length of his brother’s and father’s work, and of traditional song-poetry in general. The city ceilidh with a structured list of performers perhaps had greater time pressures than the ones in the Highlands. Niall’s regularity of rhyme and rhythm also makes for easier memorisation and execution than the more conversational rhythms of Iain’s and Dòmhnall’s poetry. Niall’s metres were praised by Sorley MacLean as being ‘exquisite in modulation and even in general technique’, but were criticised by Derick Thomson who made a connection between their rhythmic regularity and their lack of surprise, shock, and tension.xxxiii In his thinking too, Niall follows simple formulas. Very often he describes the land, then the nostalgia it awakens, and closes with a rallying call for recovery, or with a pointer to the fragility of life. All of Niall’s poems are rounded off with some clear message or conclusion, but because Iain’s songs were aimed at a known audience, they are not always self-explanatory, e.g. ‘Òran Catrìona Ghrannda’, and some end abruptly.xxxiv ‘Mo Mhàthair an Àirnicreap’ (no. 34) describes Iain’s dangerous life at sea and his longing for home, and ends with the couplet:

Nach sona dhuts’, a Fhionnlaigh,

Gun do dh’ionnsaich thu cur is buain.

Weren’t you lucky, Finlay,

that you learnt to sow and reap.

His audience would have understood what lay behind his envy of Finlay: Finlay was Iain’s brother who stayed at home to work the croft.

The three have a distinctly different tenor to their language. Dòmhnall’s language has an 18th density and exuberance. We saw this in his seafaring poem above. His poem to a grassy hillock in Glendale called Tungag recalls Mac Mhaighstir Alasdair’s nature poetry – and even quotes from it – while his Day of Judgement brings Dùghall Bochanan to mind. In Niall, there is a limited centralised vocabulary and a new Victorian prettiness combined with the influence of MacPherson. Love swims in the face of Màiri Bhaile-Chró (No. 4, v. 6); the sun dries a daisy’s tears (‘Rainn do Neòinean’, no. 29); the wind laments lost warriors and the departed population in ‘Fàilte don Eilean Sgitheanach’ and ‘Mhuinntir a’ Ghlinne seo’ (nos. 2 and 12). This is quite different from the rocks, An t-Aigeach and An Ceannaiche, speaking to Iain Dubh, because the wind had never spoken in Gaelic before James MacPherson’s time, while the rocks had been talking since the Lia Fáil.

Some of Niall’s poetic ideals are made explicit in his correspondence with Alexander MacDonald about the latter’s Còinneach ’us Coille (Inverness 1895). He expresses views on the divine provenance of poetry and its edifying nature:

How is your book doing? I hope it is selling well. Gaelic publications seldom or never pay, at least that is my experience in my own humble efforts. Good many Highlanders are very patriotic till you touch their pockets and then their patriotism vanishes. But my dear friend, that should not drown the poetic flame. The mavis and lark don’t sing with a view to a reward but because it is the talent that God gave them and they use it well. Poetry is a divine gift if properly directed. Although the poetic sentiment is almost sneered at in this commercial and prosaic age. Still it must be admitted that we are indebted to the bards for much of what is noble, pure and sweet in the language and literature of our country.xxxv

When pressed to give a candid view of the younger poet’s work, he praises his poems for being sweet and ‘singable’ but criticises him for contracting some words. Niall shows a preference for the literary rather than spoken forms of the language, and concomitant with that, perhaps, a taste for gracefulness:

Of course there are cases in writing poetry where one is obliged to contract and twist words for the sake of the rhyme and measure, but the less of that the better. In composing poetry we ought to endeavour to clothe our thoughts and ideas with the most graceful and fitting words at our command.xxxvi

For all his advocacy of non-violence in the Land Wars, for all his lack of understanding of Highland history, and his unwarranted hope for the restoration of the population and their language in the Highlands, Niall was more politically aware than either his brother or father who, I think, make no mention of the Clearances. Sorley MacLean has written of Neil in this regard:

Niall MacLeod …had no deficiency in intellect, and his fine sensitive nature reacted keenly to the tragedy of his people, but he was incapable of expressing a militant ardour … incapable of bitterness and incapable of the adequate expression of strong indignation, and he saw human life as sad whether the sorrow was of a particular or universal nature.xxxvii

MacLean points out that ‘Poetic sincerity is not the same thing as moral sincerity’, so although Niall wrote poetry in which he expressed indignation at the treatment of the Highlanders, Sorley felt that they were not as convincing as his poems of nostalgia.

Though Niall might be said to have created a new genre of emigré verse, it is important to recognise those places where he still worked within the Gaelic tradition which he clearly knew well. (We see him for example helping Frances Tolmie with her transcriptions of Gaelic song while both were resident in Edinburgh.xxxviii) In writing elegies for prominent city Gaels (e.g. nos. 31 and 32), Niall fulfilled the traditional role of the Gaelic poet, by commemorating the dead and holding up their virtues to others. Just as his father had used tree imagery in his Lament for Captain MacLeod, and Iain had been shocked by his neighbour’s cutting of branches from a tree in Cille Comhghain cemetery, so too does Niall use tree imagery to praise not a warrior but the academic, Professor Blackie:

Ghearradh a’ chraobh bu torach blàth,

’S a dh’àraich iomadh meanglan òg,

Bu taitneach leam a bhith fo sgàil,

’S mo chàil a’ faotainn brìgh a lòin.

The tree of fruitful blossom has been felled,

which nurtured many a young shoot,

it was my delight to be in its shade,

my appetite nourished from its fruit.

Niall seeks seclusion to enable him to experience the beauty of the Highland landscape without the evidence of the Clearances (e.g. in ‘Ri Taobh na Tràigh’, no. 30). The idyll of seclusion and of finding comfort and companionship in nature is at least as old in Gaelic as the hermetic poetry of the 6th – 9th centuries, and the traditions of Mad Sweeney of the 9th –12th centuries. However, the emptiness of the Highlands is itself a sign of Clearance, so the beauty of the landscape for Niall is always synonymous with sadness.

Judging by the number of people who knew the eighty-eight poems in Clàrsach an Doire by heart,xxxix and by the demand for his book which has run to six editions, it is clear that the Gaels have relished Niall’s songs, whatever late 20th century critics may say. Two poems from the time of his death (see below) show how intensely his death was felt by Gaels in the Lowlands and Highlands alike.

People appreciate Neil’s poems’ shortness, their simple language and rhythms, their availability in book form and their ability to stand alone without explanation. They were a mass-produced product for the Gaels working in the industries of the Lowlands when they came together socially. In such a situation they would not want the songs of protest and anguish that were part of land league rallies; rather they wanted a balm to heal the wounds of recent history, of Clearance and war.xl The social function of Niall’s poetry was to give people, who historically would have felt little commonality, a group identity, based on a shared Highland upbringing, a shared language, and a shared nostalgia and concern for their homelands. Niall’s songs expressed, and were shaped by, the closeness and affection that were the glue of such gatherings. But without their music, the words of songs live only a half-life.xli We should be careful about judging Gaelic song as poetry, nor should we forget that Niall’s work may have worked all the better for its relative simplicity. The fusion of melody with easy-flowing versification in the evocation of an idyll gave thousands a sense of pride in their past, a sense of common purpose and optimism about their new lives.

It is hoped this book will allow for a reassesment of Niall’s work in the context of his family and of the Gaelic diaspora. Though neither son displays the linguistic capacity nor dialectic power of his father, a sample of whose work is edited and translated here for the first time, it will probably be agreed that the main fault-line runs between Niall on one side and his father and younger brother on the other. But perhaps the greater revelation, at least for people outwith Duirinish, will lie in the publication of all Iain Dubh’s surviving songs and poems. We are indebted to the people in his neighbourhood like Sam Thorburn and Ùisdean MacRath a thug leotha iad, ‘who took them with them’, but with their sense of fun and of place, with their informality and intensity of feeling, it is not hard to see why they did so.

TWO POEMS ON NEIL MACLEOD’S DEATH

1. Rannan Cuimhneachain air Niall MacLeod, am Bàrd

le ‘Domhnullach’ (1860-1928)

1. Is ann an uair a bha ’m Foghar òirdhearc

Na làn mhaisealachd is bhòidhchead,

’S na chulaidh sgiamhach bhallach òrbhuidh,

Fo shràchd ga bhuain,

A chuala sinn an sgeula brònach

Bu deòin leinn bhuainn.

2. Gun tàinig spealadair nan aoisean

A-nall bho dhìomhaireachd nan saoghal,

’S gun tug e leis bho thìr chlann-daoine,

Gu dùthaich fhèin,

Am Bàrd MacLeòid, ’s tha sinne faoin deth,

Is Niall gun fheum.

3. Am Bàrd bu bhinne ceòl is clàrsachd,

Am bàrd bu mhìlse guth is gàire;

Bàrd nan doire dlùth is nam blàth-dhail,

Bàrd nan gleanntan;

Bàrd nan cnoc, nan loch, ’s nan làn-choill,

’S bàrd nam beanntan.

4. Am bàrd bu chuthag is bu smeòrach,

Bu lòn-dubh is bu bhrù-dhearg còmhla;

’S mar an uiseig air chùl òrain,

Bu bhòidhche gleusadh;

Bàrd nam braon, nan gaoth ’s nan neòlaibh,

’S bàrd na grèine.

5. Bha do chridhe mar theudan clàrsaich,

’S dhannsadh ceòl is cainnt bho d’ fhàilte;

’S cha b’ urra’ dhuit a chleith air càcha

Do mhòr-èibhneis,

Ri na bha nad shealladh àillidh

Fo chuairt nan speuran.

6. ’S bha do bhlàth-shùil donn mar sgàthan

A’ sìor dheàlradh oibribh Nàdair,

Mar bu bhrèagha is mar a b’ àlainn

A’ tighinn fod chomhair;

’S fhuair thu lorg air breab neo-bhàsmhor

Cridhe ’n domhain.

7. ’S chan ann gun adhbhar tha na Gàidheil

Uileadh pròiseil à do bhàrdachd;

’S thug thu togail dan a’ Ghàidhlig

Fad an t-saoghail;

’S chuir thu ’m broilleach Alba bràiste,

’S cha bu shaor e.

8. Ach rug an uair ort – uair ar dunaich,

Uair nam buadh is na buana guinich;

Thriall i leat is cha till thu tuilleadh,

Gu tìr nam beò;

An talla nam bàrd gu là na cruinne

Bithidh Niall MacLeòid.

Memorial Verses on Neil MacLeod, the Poet by Alexander MacDonald

1. It was when the glorious harvest

was at its height of grace and beauty,

in its fair, dappled, golden garments,

harvested in swathes,

that we heard the sorry tidings

we’d sooner not have.

2. That the reaper of generations

crossed over from mysterious ages

and took him, away from the land of the living

to his own land,

the poet MacLeod, and we are made feeble

by Neil being dead.

3. The bard of the sweetest song and harping,

the bard of most melodious voice and laughter;

bard of dense groves and flower-strewn meadows,

bard of the valleys;

bard of the hills, the lochs and woodlands,

bard of the mountains.

4. The bard who was both cuckoo and mavis,

the blackbird and the robin together;

who behind a song was like the skylark

of finest tuning;

bard of the dews, the winds and clouds,

bard of the sun.

5. Your heart was like the strings of the clàrsach,

music and chatter would dance at your welcome;

and you could not hide from others

your ecstasy

at what appeared lovely to your gaze

under turning skies.

6. Your warm brown eye was like a mirror

always illuminating the works of Nature,

everything beautiful and comely

coming into your view,

and you detected the eternal beat

of the heart of the world.

7. It isn’t without reason that the Gaels

were all proud of your poetry;

you raised up the Gaelic language

throughout the world,

and pinned a brooch on Scotland’s bosom

that was not tawdry.

8. But time caught up with you – the hour of our undoing,

the hour of virtues and the wounding harvest;

time took you away and you’ll return no more

to the land of the living;

in the hall of the poets till the day of judgement

Neil MacLeod will be.

2.Cumha Nèill MhicLeòidgun urra1. Chaidh sgeula tron tìr so dh’fhàg mìltean fo phràmh

Mo lèireadh bhith ’g innseadh an nì sin ro-chràit’,

An treun-fhear ro-phrìseil de chinneadh nan sàr

Don eug rinn e strìochdadh, ’s e sìnte fon làr.

2. Air fraoch-bheannaibh stùcach, cluinn giucal a’ bhròin

Sa ghaoith mhòir a’ diùltainn a ghiùlan le deòin,

Ghuil caointeach gu tùrsach; sguir buileach na h-eòin,

Thaom Cuiltheann na sruthain fo churrachd den cheò.

3. Chrom bileagan cùbhraidh san uair sin an cinn

Cò nis a bheir cliù dhaibh on dh’fhalbh ’s nach till

Bard fileanta speileanta ealanta grinn,

Fear macanta bàidheil, balbh anns a’ chill?

4. Chan fhaicear e tuilleadh aig Faidhir no aig Mòd,

Mo gheur-lot, an curaidh bhith laighe fon fhòid,

Mac-Alla ag aithris le fann-ghuth gun treòir

‘Cha mhaireann, cha mhaireann, cha mhaireann MacLeòid!’

5. Cha mhaireann an gaisgeach a sheasadh sa chàs,

Chaill Ghàidhlig cul-taice nach faigh i gu bràth,

Thuirt e rithe ’s i meata, ‘Na gabh geilte no sgàth,

Chan aontaich mi ’m feasta gum faigh thu am bàs’.

6. Dh’fhàg e dìleab na dhèidh nach tuigear a luach,

Feadh bhios filleadh na gaoith mu mhullach nan cruach,

Dh’fhàg e mìltean ga chaoidh mu Dheas is mu Thuath,

Mo mì-ghean ’s mo lèireadh gum feumar a luaidh!

7. Cò ghleusas a’ chlàrsach, cò thogas am fonn?

Cò dhùisgeas a’ cheòlraidh à suain-chadal trom?

Cò sheinneas le caithream air euchdan nan sonn?

Mo sgaradh, mo sgaradh, geur acaid nam chom!

8. Mhic Leòid, a Mhic Leòid, fhir gun ghò is gun bheud,

Fhir mhodhail, chiùin, chòir, fhir fhòghlaimte ghleust’,

Fhir mhòir am measg shlòigh, theich m’ aighear ’s mo ghleus

Cha d’ fhàg thu do choimeas san àl seo ad dhèidh.

9. Tha lionn-dubh is iargain a’ lìonadh nan gleann,

Cumhadh dubhach is tuireadh air filidh nam beann,

Mo dhùil anns a’ Chruithear chaidh gu bàs air a’ chrann

E thoirt sìth is furtachd don bhantraich ’s don chlann.

10. Geug àlainn an fhìonain rinn cinntinn cho àrd,

Lùb measan a-sìos i ’s bu rìomhach a blàth,

Rinn aois mhòr tro lìnntean a crìonadh on bhàrr,

’S rinn fuar-ghaoth nan siantan a bristeadh gu làr.

11. Mo shòlas bhi ’g aithris, thu bhith marbh san fheòil,

Mo shòlas, a charaid, tha d’ anam glè bheò,

Gun còmhlaich sinn fhathast, tha mo dhòchas ro-mhòr

An Còisir nam Flaitheas tha seinn ann an Glòir.

A Lament for Neil MacLeod anonymous

1. News swept through this land that left thousands depressed,

it’s my misfortune to tell of this terrible thing,

that this beloved man of the warrior race

has yielded to death and is laid in the earth.

2. On heather-covered peaks hear sorrow moan

in the great wind resenting carrying it free;

a mourner wept sadly, the birds have fallen quiet,

the Cuillin poured forth torrents below its cap of mist.

3. Fragrant flowers at that time bent their heads

for who will spread their fame now he’s gone and won’t return,

a poet who was melodious, eloquent, elegant, fine,

a modest, kind man now dumb in the grave?

4. He’ll be seen no more at fair or at Mod,

my agony, the hero to be lying below the sod,

with Echo repeating in a weak voice without strength,

‘No more, no more, no more is MacLeod.’

5. No more is the warrior who stood in the breach –

Gaelic has lost a support she’ll never find again,

he told her, when she grew faint, ‘Neither fear nor yield,

I’ll never allow that you will die’.

6. He left a legacy whose worth can’t be gauged,

as long as the plaiting of the wind is round the peaks,

he has left thousands lamenting him South and North,

alas and alack that it has to be told.

7. Who will tune the harp, who will sing the song,

who will waken the muses from heavy sleep,

who will declaim about heroic feats,

my undoing is the sharp pain in my breast.

8. MacLeod, MacLeod, man without guile or deceit,

courteous, kind, gentle, learned, cultured man,

Oh great man amongst peoples, all joy has fled,

in this generation after you, none can compare.

9. Melancholy and dejection are filling the glens,

dark lament and mourning for the poet of the hills,

my hope in the Creator who died on the Cross

that He will give comfort to the widow and the young.

10. A branch of the vine that grew so high,

that was bent with fruit and lovely in bloom,

great age through the centuries caused its decline

and cold stormy winds smashed it to the ground.

11. My comfort in relating you’ve died in the flesh,

my comfort, dear friend, is that your soul lives on,

that we will meet yet is my great hope,

singing in Glory in the heavenly choir.

A Note on Editorial and Translation Practice

The translations that follow are intended to provide help to the Gaelic learner, particularly with the more obscure language of Dòmhnall nan Òran, while giving the reader with no Gaelic a sense of the song-like qualities of the originals. The translations therefore are literal, following the originals line by line, and scanning similarly. No attempt has been made to follow the rhyme schemes of the Gaelic.

Niall’s language is very simple and seldom causes difficulties in translation or interpretation. Eleven translations by Niall and others were published in the 1902 edition of Clàrsach an Doire and fifteen in the 1909 edition. Because of the license taken to make them rhyme and to give the mood of the Gaelic, they are not as useful a crib as the translations in this volume. However, the names of the translators are interesting in indicating the members of Niall’s circle: ‘Fionn’, D. Mackay (Ledaig), Duncan Livingstone (Ohio), P. Macnaughton, Mrs Mary Mackellar, Neil Ross and Malcolm Macfarlane.

Of the sixteen songs and poems by Iain Dubh in this volume, four have been taken from unpublished sources and two from sound recordings. Only two of Iain Dubh’s songs have been previously translated, no. 33. ‘Gillean Ghleann Dail’ and no. 34. ‘Mo Mhàthair an Àirnicreap’.

None of Dòmhnall nan Òran’s texts have been previously translated but they all have a written source. The texts are much easier to follow in his Dàin agus Orain of 1871 than in his Orain Nuadh Ghaelach of 1811. Reconstructions, where there is considerable doubt, have been marked in the notes. Dòmhnall clearly delighted in old and unusual words, and goes to great lengths to choose and spell words according to metrical requirements. In one case (no. 49 v. 3), he chooses the wrong word for wine glasses, spiaclan (spectacles), in order to make internal rhyme with fhìona (wine).

The metrics are always a help in divining what words might be, whether spelled irregularly for metrical purposes or out of spelling conventions. MacDiarmid rightly considered that his texts were not exceptional for the times:

No doubt such errors are somewhat conspicuous in his old book; but it is only fair to state that that book was edited by a gentleman in whose Gaelic scholarship MacLeod had great confidence. He is not, therefore, altogether responsible for the many errors in grammar, spelling, accentuation, and punctuation, which are so glaring in this old collection. With careful editing, these faults would not have been more obtrusive than similar ones in some of our best Gaelic books (MacDiarmid 1888: 23-24).

An attempt has been made to apply current Gaelic orthographic conventions to all the texts, while not obscuring rhyme, dialectal or idiolectal variation. Where there is a choice between spelling to reflect the rhyme scheme or to reflect dictionary citations, precedence is given to the rhyme. Dòmhnall has a tendency to use datives, both singular an plural, for the nominative/accusative (e.g. no. 56: 7 Ged a shàraich thu an drannaig; and no. 58:12 Càit a-nis am bheil na h-eachaibh). He also uses dative plurals as genitive plurals (e.g. no. 56:11 beanachd leanaibh is mhàthraibh). Plurals are often formed by slenderisation rather than by suffix (e.g. no. 59: No ’m bheil do bhuaidh agad uait fhèin?)

A double letter indicates vowel length, e.g. loinneagach for lòineagach; roinneagach for ròineagach.

Where there are several versions of a song, the oldest or most complete version has been selected, but certain lines have been supplied by other versions where they give a preferable reading. Variations are marked in the notes.

The question arises whether to write a verse as four long lines or eight shorter lines. The second option has generally been chosen as this has become conventional, though it is clear from the way such songs are sung that the basic unit is the long line. It is hoped that this deficiency will be reduced by the electronic links to the sound archives, Tobar an Dualchais or the BBC’s Bliadhna nan Òran.

No musical notation is given in