Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

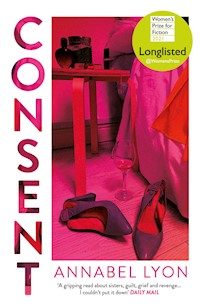

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

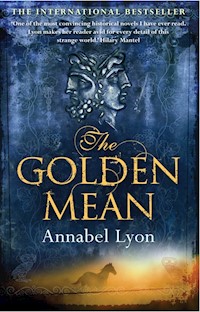

Shortlisted for the prestigious Giller Prize and the Governor General's Award Macedon. 367 BC. Philip II is bringing war to Persia. Forged in the warrior culture of Macedonia, the time has come for his young son Alexander to take up his inheritance of blood and obedience to the sword. It is a training that has made the boy sadistic; fiercely brilliant, but unstable. A dangerous trait in a king fated to rule the vastest empire of the ancient world. Compelled to teach this startling, precocious, sometimes horrifying child, Aristotle soon realises that what the boy needs most to learn - thrown before his time onto his father's battlefields - is the lesson of the golden mean, the elusive balance between extremes that Aristotle hopes will mitigate the boy's will to conquer in this age of fighting heroes...

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 406

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2010

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE GOLDEN MEAN

Annabel Lyon is the author of two short story collections, Oxygen and The Best Thing for You. The Golden Mean, her first novel, was short-listed for all the major literary prizes in Canada, winning the Rogers Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize. Annabel Lyon lives in British Columbia with her husband and two children.

ALSO BY ANNABEL LYON:

Oxygen

The Best Thing for You

Copyright

First published in Canada in 2009 by Random House Canada,a division of Random House of Canada Limited.

First published in Great Britain in hardback and airport and export tradepaperback in 2010 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd.

Copyright © Annabel Lyon, 2009

The moral right of Annabel Lyon to be identified as the author ofthis work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright,Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may bereproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form orby any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise,without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and theabove publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, charactersand incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination andnot to be construed as real. Any resemblance to actual persons, living ordead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

First eBook Edition: January 2010

ISBN: 978-0-857-89059-7

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

Contents

Cover

THE GOLDEN MEAN

ALSO BY ANNABEL LYON

Copyright

CAST (IN ORDER OF APPEARANCE)

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

AFTERWORD

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

A NOTE ABOUT THE TYPE

For my parents,

my children,

and Bryant.

CAST (IN ORDER OF APPEARANCE)

Aristotle, a philosopher

Callisthenes, Aristotle’s nephew and apprentice

Pythias, Aristotle’s wife

Hermias, satrap of Atarneus, Aristotle’s former patron

Philip, king of Macedon

Phila, Audata, Philinna, Nikesipolis, wives of Philip

Olympias, wife of Philip, queen of Macedon

Leonidas, one of Alexander’s tutors

Carolus, a theatre director

Demosthenes, an Athenian orator, enemy of Philip

Arrhidaeus, son of Philip and Philinna, elder half-brother of Alexander

Philes, Arrhidaeus’s nurse

Alexandros, king of Molossos, Olympias’s brother

Antipater, a general, regent in Philip’s absence

Alexander, son of Philip and Olympias

Arimnestus and Arimneste, twins, Aristotle’s younger brother and sister

Proxenus, husband of Arimneste, Aristotle’s guardian after his parents’ deaths

Amyntas, Philip’s father, king of Macedon

Illaeus, a student of Plato, Aristotle’s tutor

Perdicaas, Philip’s elder brother, king of Macedon after Amyntas’s death

Euphraeus, a student of Plato, Perdicaas’s tutor

Hephaestion, Alexander’s closest companion

Ptolemy, another of Alexander’s companions

Lysimachus, one of Alexander’s tutors

Pausanias, a Macedonian officer, later one of Philip’s bodyguard

Tycho, a slave of Aristotle

Artabazus, a Persian refugee in the Macedonian court

Athea, a slave of Aristotle

Meda, sixth wife of Philip

Little Pythias, Aristotle and Pythias’s daughter

Xenocrates, a philosopher, Speusippus’ successor as director of the Academy

Eudoxus, a philosopher, director of the Academy in Plato’s absence

Callippus, a philosopher, companion of Eudoxus

Nicanor, son of Arimneste and Proxenus

Plato, a philosopher, director of the Academy

Speusippus, Plato’s nephew, director of the Academy after his uncle’s death

Herpyllis, Pythias’s maid, Aristotle’s companion after Pythias’s death

Cleopatra, seventh wife of Philip

Attalus, father of Cleopatra

Eurydice, daughter of Philip and Cleopatra

Pixodarus, satrap of Caria, Arrhidaeus’s potential father-in-law

Thessalus, an actor

Nicomachus, Aristotle and Herpyllis’s son

IT MUST BE BORNE in mind that my design is not to write histories, but lives. And the most glorious exploits do not always furnish us with the clearest discoveries of virtue or vice in men; sometimes a matter of less moment, an expression or a jest, informs us better of their characters and inclinations, than the most famous sieges, the greatest armaments, or the bloodiest battles whatsoever.

Plutarch, Alexandertranslated by John Dryden

ONE

THE RAIN FALLS IN black cords, lashing my animals, my men, and my wife, Pythias, who last night lay with her legs spread while I took notes on the mouth of her sex, who weeps silent tears of exhaustion now, on this tenth day of our journey. On the ship she seemed comfortable enough, but this last overland stage is beyond all her experience and it shows. Her mare stumbles; she’s let the reins go loose again, allowing the animal to sleepwalk. She rides awkwardly, weighed down by her sodden finery. Earlier I suggested she remain on one of the carts but she resisted, such a rare occurrence that I smiled, and she, embarrassed, looked away. Callisthenes, my nephew, offered to walk the last distance, and with some difficulty we helped her onto his big bay. She clutched at the reins the first time the animal shifted beneath her.

“Are you steady?” I asked, as around us the caravan began to move.

“Of course.”

Touching. Men are good with horses where I come from, where we’re returning now, and she knows it. I spent yesterday on the carts myself so I could write, though now I ride bareback, in the manner of my countrymen, a ball-busting proposition for someone who’s been sedentary as long as have. You can’t stay on a cart while a woman rides, though; and it occurs to me now that this was her intention.

I hardly noticed her at first, a pretty, vacant-eyed girl on the fringes of Hermias’s menagerie. Five years ago, now. Atarneus was a long way from Athens, across the big sea, snug to the flank of the Persian Empire. Daughter, niece, ward, concubine— the truth slipped like silk.

“You like her,” Hermias said. “I see the way you look at her.” Fat, sly, rumoured a money-changer in his youth, later a butcher and a mercenary; a eunuch, now, supposedly, and a rich man. A politician, too, holding a stubborn satrapy against the barbarians: Hermias of Atarneus. “Bring me my thinkers!” he used to shout. “Great men surround themselves with thinkers! I wish to be surrounded!” And he would laugh and slap at himself while the girl Pythias watched without seeming to blink quite often enough. She became a gift, one of many, for I was a favourite. On our wedding night she arrayed herself in veils, assumed a pose on the bed, and whisked away the sheets before I could see if she had bled. I was thirty-seven then, she fifteen, and gods forgive me but I went at her like a stag in rut. Stag, hog.

“Eh? Eh?” Hermias said the next morning, and laughed.

Night after night after night. I tried to make it up to her with kindness. I treated her with great courtliness, gave her money, addressed her softly, spoke to her of my work. She wasn’t stupid; thoughts flickered in her eyes like fish in deep pools. Three years we spent in Atarneus, until the Persians breathed too close, too hot. Two years in the pretty town of Mytilene, on the island of Lesvos, where they cobbled the floor of the port so enemy ships couldn’t anchor. Now this journey. Through it all she has an untouchable dignity, even when she lies with her knees apart while I gently probe for my work on generation. Fish, too, I’m studying, field animals, and birds when I can get them. There’s a seed like a pomegranate seed in the centre of the folds, and the hole frilled like an oyster. Sometimes moisture, sometimes dryness. I’ve noted it all.

“Uncle.”

I follow my nephew’s finger and see the city on the marshy plain below us, bigger than I remember, more sprawling. The rain is thinning, spitting and spatting now, under a suddenly lucid gold-grey sky.

“Pella,” I announce, to rouse my dripping, dead-eyed wife. “The capital of Macedon. Temple there, market there, palace. You can just make it out. Bigger than you thought?”

She says nothing.

“You’ll have to get used to the dialect. It’s fast, but not so different really. A little rougher.”

“I’ll manage,” she says, not loudly.

I sidle my horse up to hers, lean over to take her reins to keep her near me while I talk. It’s good for her to have to listen, to think. Callisthenes walks beside us.

“The first king was from Argos. A Greek, though the people aren’t. Enormous wealth here: timber, wheat, corn, horses, cattle, sheep, goats, copper, iron, silver, gold. Virtually all they have to import is olives. Too cold for olives this far north, mostly; too mountainous. And did you know that most of the Athenian navy is built from Macedonian timber?”

“Did we bring olives?” Pythias asks.

“I assume you know your wars, my love?”

She picks at the reins, plucks at them like lyre strings, but I don’t let go. “I know them,” she says finally.

Utterly ignorant, of course. If I had to weave all day, I’d at least weave myself a battle scene or two. I remind her of the Athenian conquest of Persia under the great general Pericles, Athens at her seafaring mightiest, in my great-grandfather’s time. Then the decades of conflict in the Peloponnese, Athens bled and finally brought low by Sparta, with some extra Persian muscle, in my father’s youth; and Sparta itself defeated by Thebes, by then the ascendant power, in my own childhood. “I will set you a task. You’ll embroider Thermopylae for me. We’ll hang it over the bed.”

Still not looking at me.

“Thermopylae,” I say. “Gods, woman. The pass. The pass where the Spartans held off the Persians for three days, a force ten times their own. Greatest stand in the history of warfare.”

“Lots of pink and red,” Callisthenes suggests.

She looks straight at me for a moment. I read, Don’t patronize me. And, Continue.

Now, I tell her, young Macedon is in the ascendant, under five-wived Philip. A marriage to cement every settlement and seal every victory: Phila from Elimea, in the North; Audata the Illyrian princess; Olympias of Epirus, first among wives, the only one called queen; Philinna from Thessaly; and Nikesipolis of Pherae, a beauty who died in childbirth. Philip invaded Thrace, too, after Thessaly, but hasn’t yet taken a Thracian wife. I rifle the library in my skull for an interesting factling. “They like to tattoo their women, the Thracians.”

“Mmm.” Callisthenes closes his eyes like he’s just bitten into something tasty.

We’re descending the hillside now, our horses scuffling in the rocky scree as we make our way down to the muddy plain. Pythias is shifting in the saddle, straightening her clothes, smoothing her eyebrows, touching a fingertip to each corner of her mouth, preparing for the city.

“Love.” I put my hand on hers to still her grooming and claim back her attention. My nephew I ignore. A Thracian woman would eat him alive, tender morsel that he is, and spit out the little bones. “You should know a little more. They don’t keep slaves like we do, even in the palace. Everyone works. And they don’t have priests. The king performs that function for his people. He begins every day with sacrifices, and if anyone needs to speak to a god, it’s done through him.” Sacrilege: she doesn’t like this. I read her body. “Pella will not be like Hermias’s court. Women are not a part of public life here.”

“What does that mean?”

I shrug. “Men and women don’t attend entertainments together, or even eat together. Women of your rank aren’t seen. They don’t go out.”

“It’s too cold to go out,” Pythias says. “What does it matter, anyway? This time next week we’ll be in Athens.”

“That’s right.” I’ve explained to her that this detour is just a favour to Hermias. I’m needed in Pella for just a day or two, a week at most. Clean up, dry out, rest the animals, deliver Hermias’s mail, move on. “There isn’t much you’d want to do in public anyway.” The arts are imported sparingly. Pig-hunting is big; drinking is big. “You’ve never tasted beer, have you? You’ll have to try some before we leave.”

She ignores me.

“Beer!” Callisthenes says. “I’ll drink yours, Auntie.”

“Remember yourself,” I tell the young man, who has a tendency to giggle when he gets excited. “We are diplomats now.”

The caravan steps up its pace, and my wife’s back straightens. We’re on.

Despite the rain and ankle-sucking mud, we pick up a retinue as we pass through the city’s outskirts, men and women who come out of their houses to stare, and children who run after us, pulling at the skins covering the bulging carts, trying to dislodge some souvenir. They’re particularly drawn to the cart that carries the cages—a few bedraggled birds and small animals—which they dart at, only to retreat, screaming in pleasure and shaking their hands as though they’ve been nipped. They’re tall children, for the most part, and well formed. My men kick idly at a clutch of little beggars to fend them off, while my nephew genially turns out his pockets to them to prove his poverty. Pythias, veiled, draws the most stares.

At the palace, my nephew speaks to the guard and we are admitted. As the gates close behind us and we begin to dismount, I notice a boy—thirteen, maybe—wandering amongst the carts. Rain-plastered hair, ruddy skin, eyes big as a calf’s.

“Get away from there,” I call when the boy tries to help with one of the cages, a chameleon as it happens, and more gently, when the boy turns to look at me in amazement: “He’ll bite you.”

The boy smiles. “Me?”

The chameleon, on closer inspection, is shit-smelling and lethargic, and dangerously pale; I hope it will survive until I can prepare a proper dissection.

“See its ribs?” I say to the boy. “They aren’t like ours. They extend all the way down and meet at the belly, like a fish’s. The legs flex opposite to a man’s. Can you see his toes? He has five, like you, but with talons like a bird of prey. When he’s healthy he changes colours.”

“I want to see that,” the boy says.

Together we study the monster, the never-closing eye and the tail coiled like a strap.

“Sometimes he goes dark, almost like a crocodile,” I say. “Or spotted, like a leopard. You won’t see it today, I’m afraid. He’s about dead.”

The boy’s eyes rove across the carts.

“Birds,” he says.

I nod.

“Are they dying, too?”

I nod.

“And what’s in here?”

The boy points at a cart of large amphora with wood and stones wedged around them to keep them upright.

“Get me a stick.”

Again that look of amazement.

“There.” I point at the ground some feet away, then turn away deliberately to prise the lid off one of the jars. When I turn back, the boy is holding out the stick. I take it and reach into the jar with it, prodding gently once or twice.

“Smells,” the boy says, and indeed the smell of sea water, creamy and rank, is mingling with the smell of horse dung in the courtyard.

I pull out the stick. Clinging to its end is a small crab.

“That’s just a crab.”

“Can you swim?” I ask.

When the boy doesn’t reply, I describe the lagoon where I used to go diving, the flashing sunlight and then the plunge. This crab, I explain, came from there. I recall going out past the reef with the fishermen and helping with their nets so I could study the catch. There, too, I swam, where the water was deeper and colder and the currents ran like striations in rock, and more than once I had to be rescued, hauled hacking into a boat. Back on shore the fishermen would build fires, make their offerings, and cook what they couldn’t sell. Once I went out with them to hunt dolphin. In their log canoes they would encircle a pod and slap the water with their oars, making a great noise. The animals would beach themselves as they tried to flee. I leapt from the canoe as it reached shore and splashed through the shallows to claim one of them for myself. The fishermen were bemused by my fascination with the viscera, which was inedible and therefore waste to them. They marvelled at my drawings of dissections, pointing in wonder at birds and mice and snakes and beetles, cheering when they recognized a fish. But as orange dims to blue in a few sunset moments, so in most people wonder dims as quickly to horror. A pretty metaphor for a hard lesson I learned long ago. The larger drawings—cow, sheep, goat, deer, dog, cat, child—I left at home.

I can imagine the frosty incomprehension of my colleagues back in Athens. Science is the work of the mind, they will say, and here I am wasting my time swimming and grubbing.

“We cannot ascertain causes until we have facts,” I say. “That above all must be understood. We must observe the world, you see? From the facts we move to the principles, not the other way round.”

“Tell me some more facts,” the boy says.

“Octopuses lay as many eggs as poisonous spiders. There is no blood in the brain, and elsewhere in the body blood can only be contained in blood vessels. Bear cubs are born without articulation and their limbs must be licked into shape by their mothers. Some insects are generated by the dew, and some worms generate spontaneously in manure. There is a passage in your head from your ear to the roof of your mouth. Also, your windpipe enters your mouth quite close to the opening of the back of the nostrils. That’s why when you drink too fast, the drink comes out your nose.”

I wink, and the boy smiles faintly for the first time.

“I think you know more about some things than my tutor.” The boy pauses, as though awaiting my response to this significant remark.

“Possibly,” I say.

“My tutor, Leonidas.”

I shrug as though the name means nothing to me. I wait for him to speak again, to help or make a nuisance of himself, but he darts back into the palace, just a boy running out of the rain.

Now here comes our guide, a grand-gutted flunky who leads us to a suite of rooms in the palace. He runs with sweat, even in this rain, and smiles with satisfaction when I offer him a chair and water. I think he is moulded from pure fat. He says he knows me, remembers me from my childhood. Maybe. When he drinks, his mouth leaves little crumbs on the inner lip of the cup, though we aren’t eating.

“Oh, yes, I remember you,” he says. “The doctor’s boy. Very serious, very serious. Has he changed?” He winks at Pythias, who doesn’t react. “And that’s your son?”

He means Callisthenes. My cousin’s son, I explain, whom I call nephew for simplicity; he travels with me as my apprentice.

Pythias and her maids withdraw to an inner room; my slaves I’ve sent to the stables. We’re too many people for the rooms we’ve been allotted, and they’ll be warm there. Out of sight, too. Slavery is known here but not common, and I don’t want to appear ostentatious. We overlook a small courtyard with a blabbing fountain and some potted trees, almond and fig. My nephew has retreated there to the shelter of a colonnade, and is arguing some choice point or other with himself, his fine brows wrinkled and darkened like walnut meats by the knottiness of his thoughts. I hope he’s working on the reality of numbers, a problem I’m lately interested in.

“You’re back for the good times,” the flunky says. “War, waah!” He beats his fat fists on his chest and laughs. “Come to help us rule the world?”

“It’ll happen,” I say. “It’s our time.”

The fat man laughs again, claps his hands. “Very good, doctor’s son,” he says. “You’re a quick study. Say, ‘I spit on Athens.’”

I spit, just to make him laugh again, to set off all that wobbling.

When he’s gone, I look back to the courtyard.

“Go to him,” Pythias says, passing behind me with her maids, lighting lamps against the coming darkness.

In other windows I can see lights, little prickings, and hear the voices of men and women returning to their rooms for the evening, public duties done. Palace life is the same everywhere. I was happy enough to get away from it for a time, though I know Hermias was disappointed when we left him. Powerful men never like you to leave.

“I’m fine here,” Pythias says. “We’ll see to the unpacking. Go.”

“He hasn’t been able to get away from us for ten days. He probably wants a break.”

A soldier arrives to tell me the king will see me in the morning. Then a page comes with plates of food: fresh and dried fruit, small fish, and wine.

“Eat,” Pythias is saying. Some time has passed; I’m not sure how much. I’m in a chair, wrapped in a blanket, and she is setting a black plate and cup by my foot. “You know it helps you to eat.”

I’m weeping: something about Callisthenes, and nightfall, and the distressing disarray of our lives just now. She pats my face with the sleeve of her dress, a green one I like. She’s found time to change into something dry. Wet things are draped and swagged everywhere; I’m in the only chair that hasn’t been tented.

“He’s so young,” she says. “He wants a look at the city, that’s all. He’ll come back.”

“I know.”

“Eat, then.”

I let her put a bite of fish in my mouth. Oil, salt tang. I realize I’m hungry.

“You see?” she says.

There’s no name for this sickness, no diagnosis, no treatment mentioned in my father’s medical books. You could stand next to me and never guess my symptoms. Metaphor: I am afflicted by colours: grey, hot red, maw-black, gold. I can’t always see how to go on, how best to live with an affliction I can’t explain and can’t cure.

I let her put me to bed. I lie in the sheets she has warmed with stones from the hearth, listening to the surf-sounds of her undressing. “You took care of me today,” I say. My eyes are closed, but I can hear her shrug. “Making me ride. You didn’t want them laughing at me.”

Redness flares behind my closed eyelids; she’s brought a candle to the bedside.

“Not tonight,” I say.

Before we were married, I gave her many fine gifts: sheep, jewellery, perfume, pottery, excellent clothes. I taught her to read and write because I was besotted and wanted to give her something no lover had ever thought of before.

The next morning I see the note she’s left for me, the mouse-scratching I thought I heard as I slipped into sleep: warm, dry.

MY NEPHEW IS STILL sprawled on his couch when I pass through his room on my way to my audience. He’s drunk and has been fucked: face rosy and sweet, sleep deep, smell of flowers unpleasantly sweet. We’ll all want baths, later. Another grey day, with a bite in the air and rain pending. You wouldn’t know it was spring. My mood feels delicate but bearable; I’m walking along the cliff edge, but for the moment staying upright. I may go down to the city myself, later, to scrounge a memory, something drawn up from deep in the mind’s hole.

The palace seems to have rearranged itself during my long absence, like a snake might rearrange its coils. I recognize each door and hall but not the order of them, and looking for the throne room I walk into the indoor theatre instead. “Bitch,” someone is yelling. “Bitch!”

It takes me a moment to realize he’s yelling at me.

“Get out!”

My eyes adjust to the smoky dimness. I make out a few figures on the stage, and one very angry man climbing toward me over the rows of stone seats. A plume of white hair over a good face, a great face. Killing eyes. “Get out!”

I ask him what play they’re preparing.

“I’m working.” A vein throbs by his eye. He’s right up to me now, his breath in my face. He’s wrecked, he’s a killer.

I apologize. “I got lost. The throne room—?”

“I’ll take him.”

I look down at the boy who’s suddenly appeared at my side. The boy from the gates, the one I pretended not to recognize.

The director turns away and stalks back down to his position. “Places,” he barks.

“They’re doing the Bacchae,” the boy says. “We all love the Bacchae.”

Back in the hall he raises a hand and a soldier appears. The boy goes back into the theatre before I can thank him. The soldier leads me across another courtyard and through an anteroom with an elaborate mosaic floor, a lion hunt rendered in subtly shaded pebbles. It’s been a long time since I was here. The lion’s red yawn is pink now; the azure of a hunter’s terrified gaze has faded to bird’s-egg blue. I wonder where all the colour went, if it brushed off on the soles of a thousand shoes and got wiped across the kingdom. A guard holds a curtain aside for me.

“You refined piece of shit,” the king says. “You’ve spent too long in the East. Look at yourself, man.”

We embrace. As boys we played together, when Philip’s father was king and my father was the king’s physician. I was taller but Philip was tougher: so it remains. I’m conscious of the fine, light clothing I’ve changed into for this meeting, of the fashionable short clip of my hair, of my fingers gently splayed with rings. Philip’s beard is rough; his fingernails are dirty; he wears homespun. He looks like what he is: a soldier, bored by this great marble throne room.

“Your eye.”

Philip barks once, a single unit of laughter, and allows me to study the pale rivulet of a scar through the left eyebrow, the permanently closed lid. We are our fathers now.

“An arrow,” Philip says. “A bee sting for my troubles.”

Around us courtiers laugh. Barbarians, supposedly, but I see only men of my own height and build. Small Philip is an anomaly. He wears a short beard now, but is as full-lipped as I remember him, broad-browed, with a drinker’s flush across the nose and cheeks. An amiable asshole, sprung straight from boyhood to middle age.

I left off my accounting to Pythias with Philip’s invasion of Thrace. From there he went on to Chalcidice, my own home-land, a three-fingered fist of land thrust into the Aegean. An early casualty was the village of my birth. Our caravan passed by that way, three days ago now; a significant detour, but I needed to see it. Little Stageira, strung across the saddle of two hills facing the sea. The western wall was rubble, the guard towers too. My father’s house, mine now, badly burned; the garden uprooted, though the trees seemed all right. The fishing boats along the shore, burned. Paving stones had been prised up from the streets, and the population, men and women I’d known since childhood, dispersed. The destruction was five years old. News of it had first reached me just before I left Athens and the Academy for Hermias’s court, but I couldn’t face it until now. Weeds crept their green lace over doorsteps, birds nested in empty rooms, and there was no corpse smell. Sounds: sea and gulls, sea and gulls.

“An easy journey?” Philip asks.

Macedonians pride themselves on speaking freely to their king. I remind myself we were children together, and take a breath. Not an easy journey, no, I tell him. Not easy to see my father’s estate raped. Not easy to imagine the cast of my childhood banished. Not easy to have my earliest childhood memories splotched with his army’s piss. “Poor policy,” I tell him. “To destroy your own land and terrorize your own people?”

He’s not smiling, but not angry either. “I had to,” he says. “The Chalcidician League had Athens behind it, or would have if I’d waited much longer. Wealthy, strong fortifications, a good jumping-off spot if you felt like attacking Pella. I had to close that door. You’re going to tell me we’re at peace with Athens now. We’re on the Amphictyonic Council together, best friends. I’d like nothing better, believe me. I’d like to think they’re not building a coalition against me as we speak. I’d like to think they could just learn their fucking place. Reasonably, one reasonable man to another, are they going to rule the world again? Did they ever, truly? Are they hiding another Pericles someplace? Could they take Persia again? Reasonably?”

Ah, one of my favourite words. “Reasonably, no.”

“Speaking of Persia, I think you have something for me.”

Hermias’s proposal. I hand it to Philip, who hands it to an aide, who puts it away.

“Persia,” Philip says. “I could take Persia, with a little peace and quiet at my back.”

This surprises me; not the ambition, but the confidence. “You’ve got a navy?” The Macedon of my childhood had twenty warships to Athens’s three hundred and fifty.

“Athens has my navy.”

“Ah.”

“You can’t be sweeter than I’ve been,” Philip says. “Sweeter or more accommodating or more understanding. I let them off easy every time, freeing prisoners, returning territory. Demosthenes should make a speech or two about that.”

Demosthenes, the Athenian orator who gives poisonous, roaring speeches against Philip in the Athenian assembly. I saw him once in the marketplace when I was a student. He was buying wine, chatting.

“What do you think of him?” Philip asks.

“Bilious, choleric,” I diagnose. “Less wine, more milk and cheese. Avoid stressful situations. Avoid hot weather. Chew each bite of food thoroughly. Retire from public life. Cool cloths to the forehead.”

Philip doesn’t laugh. He cocks his head to the side, looking at me, deciding something. It’s unnerving.

“The army’s moving?” I say. “I saw the preparations as we arrived. Thessaly again, is it?”

“Thessaly again, then Thrace again.” Abruptly: “You brought your family?”

“My wife and nephew.”

“Healthy?”

I thank him for his interest and return the question, ritually. Philip begins to speak of his sons. The one a champion, godling, genius, star. The other—

“Yes, yes,” Philip says. “You’ll have a look at the older one for me.”

I nod.

“Look at yourself,” Philip repeats, genuinely perplexed this time. “You’re dressed like a woman.”

“I’ve been away.”

“I make it twenty years.”

“Twenty-five. I left when I was seventeen.”

“Piece of shit,” he says again. “Where do you go fromhere?”

“Athens, to teach. I know, I know. But the Academy still rules a few small worlds: ethics, metaphysics, astronomy. In my job, you have to go where the best minds are if you want to leave your mark.”

He rises, and his courtiers around him. “We’ll hunt together before I leave.”

“It would be an honour.”

“And you’ll have a look at my son,” he says again. “Let’s see if you have some art.”

A NURSE ADMITS ME to the elder son’s room. He’s tall but his affliction makes his age difficult to guess. He walks loosely, palsied like an old man, and his eyes move vaguely from object to object in the room. While the nurse and I talk, his fingers drift up to his mouth and pluck repeatedly at his lower lip. Sitting or standing, awkwardly turning this way and that as he is instructed, he seems affable enough but is clearly an idiot. His room is decorated for a child much younger, with balls and toys and carved animals strewn on the floor. The smell is thick, an animal musk.

“Arrhidaeus,” he slurs proudly, when I ask him his name. I have to ask twice, repeating myself after the nurse tells me the boy is hard of hearing.

Despite the mask of foolishness, I can see the king his father in him, in the breadth of his shoulders and the frank laughter when something pleases him, when I take deep breaths or open my mouth as wide as I can to show the boy what I want him to do. The nurse says he’s sixteen, and had been an utterly healthy child, handsome and beloved, until the age of five. He fell ill, the nurse says, and the whole house mourned, thinking he could not possibly survive the fever, the headaches, the strange stiffness in the neck, the vomiting, and finally the seizures and the ominous lethargy. But perhaps what had happened was worse.

“Not worse.” I study the boy’s nose and ears, the extension of his limbs, and test the soft muscles against my own. “Not worse.”

Though privately I thrill to the various beauty and order of the world, and this boy gives me a pang of horror.

“Take this.” I hand Arrhidaeus a wax tablet. “Can you draw me a triangle?”

But he doesn’t know how to hold the stylus. When I show him, he crows with delight and begins to scratch wavering lines. When I draw a triangle, he laughs. Inevitably I think of my own masters at school, with their modish theories about the workings of the mind. There have been always true thoughts in him … which only need to be awakened into knowledge by putting questions to him …

“He is unused,” I say. “The mind, the body. I will give you exercises. You are his companion?”

The nurse nods.

“Take him to the gymnasium with you. Teach him to run and catch a ball. Have the masseur work on his muscles, especially the legs. You read?”

The nurse nods again.

“Teach him his letters. Aloud, first, and later have him draw them with his finger in the sand. That will be easier for him than the stylus, at least to start with. Kindly, mind you.”

“Alpha, beta, gamma,” the boy says, beaming.

“Good!” I ruffle his hair. “That’s very good, Arrhidaeus.”

“For a while my father taught both children,” the nurse says. “I was their companion. The younger one is very bright. Arrhidaeus parrots him. It doesn’t mean anything.”

“Delta,” I say, ignoring the nurse.

“Delta,” Arrhidaeus says.

“I want to see him every morning until I leave. I will give you instructions as we go along.”

The nurse holds out his hand to Arrhidaeus, who takes it. They rise to leave. Suddenly Arrhidaeus’s face lights up and he begins to clap his hands, while the nurse bows. I turn. In the doorway stands a woman my own age in a simple grey dress. Her red hair is dressed elaborately in long loops and curls, hours’ worth, fixed with gems and amber. Her skin is dry and freckled. Her eyes are clear brown.

“Did he tell you?” she asks me. “Did my husband tell you how I poisoned this poor child?”

The nurse has gone stone-still. The woman and Arrhidaeus have their arms around each other’s waists, and she fondly kisses the crown of his head.

“Olympias poisoned Arrhidaeus,” she singsongs. “That’s what they all say. Jealous of her husband’s eldest son. Determined to secure the throne for her own child. Isn’t that what they say?” Arrhidaeus laughs, clearly understanding nothing. “Isn’t it?” she asks the nurse.

The young man’s mouth opens and closes, like a fish’s.

“You may leave us,” she says. “Yes, puppet,” she adds, when Arrhidaeus insists on giving her a hug. He runs after his nurse.

“Forgive me,”I say when they’re gone. “I didn’t recognizeyou.”

“But I knew you. Philip told me all about you. Can you help the child?”

I repeat what I told the nurse, about developing the boy’s existing faculties as opposed to seeking a cure.

“Your father was a doctor, yes? But you, I think, are not.”

“I have many interests,” I say. “Too many, I’m told. My knowledge is not as deep as his was, but I have a knack for seeing things whole. That child could be more than he is.”

“That child belongs to Dionysus.” She touches her heart. “There is more to him than reason. I have a fierce affection for him, despite what you may hear. Anything you do for him, I will take as a personal favour.”

Her voice rings false, the low vibrancy of it, the formality of her sentences, the practised whiff of sex. More than reason? She sets off a simmer of irritation in me, hot and dark and not entirely unpleasant.

“Anything I can do for you, I will,” I hear myself say.

After she leaves, I return to my rooms. Pythias is instructing her maids in the laundry.

“Only gently, this time,” she’s saying. Her voice is weak and tight and high; petulant. They bow and go out with the baskets between them. “Callisthenes found a servant to show them down to the river. They’ll beat my linens with rocks again, wait and see, and say they mistook them for the bedding. They’d never have dared back home.”

“You’ll have new linens once we’re settled. Just another day or two here. Look at you, trying not to smile. You can’t wait.”

“I can wait a little longer,” she says, trying to bat my hands away.

Pretty, I called her; once, maybe. Now her hair hangs thin and lank, and her brows, ten days without tweezing, have begun to sprout rogue hairs like insect legs. The lips—thinner on top, fuller beneath, with two bites of chap from the cold and damp—I want to kiss, but that’s for pity. I pull her to me to feel the green hardness of her, the bony hips and breasts like small apples. I ask her if she’d like a bath, and her eyes close for a long moment. I am both a gross idiot and the answer to her most fervent prayer.

When we come back from the baths (which, to my deep satis faction, made her gasp: the pipes for hot and cold, hot hung with warming towels; the spout in the shape of a lion’s mouth; the marble tub; the stones and sponges; the combs and oils and files and mirrors and scents; I will bring her here every day we remain), Callisthenes is up and eating the remains of last night’s meal. Pythias withdraws to the innermost room, to her maids and her sewing. The boy looks abashed but pleased with himself also. Laughing Callisthenes, with his curls and freckles. He has a sweet nature and a nimble mind and makes connections others can’t, darting from ethics to metaphysics to geometry to politics to poetics like a bee darts from flower to flower, spreading pollen. I taught him that. He can be lazy, too, though, like a sun-struck bee. I worry about him from both sides of the pendulum: that he’ll leave me, that he’ll never leave me.

“Had a good time?” I say. “Out again tonight?” Jealousy pinches my sentences, but I can’t stop myself. The pendulum swings hard left today.

“Come with me,” he says. I tell him I have to work, and he groans. “Come with me,” he says. “You can be my guide.”

“I can be your guide here,” I say.

“I thought I caught a glimpse of the number three last night, by the flower stall in the market,” he says. “It was hiding behind a sprig of orange blossom.”

“Known for shyness, the number three,” I say.

“Is Pella much bigger than you remember?”

“I wouldn’t remember a thing,” I say truthfully. “The city has probably tripled in size. I got lost this morning trying to find the baths just here in the palace.”

“Wouldn’t you like to find your father’s old house?”

“I think it’s part of the garrison now. Shall I show you the baths now that I know the way? We can work after that. You still have a headache, anyway.”

“Headache,” Callisthenes confirms. “Bad wine. Bad everything, really. Or not bad, but—vulgar. Have you seen the houses? They’re huge. And gaudy. Like these mosaics everywhere. The way they talk, the way they eat, the music, the dancing, the women. It’s like there’s all this money everywhere and they don’t know what to do with it.”

“I don’t remember it that way,” I say. “I remember the cold, and the snow. I’ll bet you’ve never seen snow. I remember the toughness of the people. The best lamb, mountain lamb.”

“I saw something last night,” Callisthenes says. “I saw a man kill another man over a drink. He held him by the shoulder and punched him in the gut over and over until the man bled out of his ears and his mouth and his eyes, weeping blood, and then he died. Everyone laughed. They just laughed and laughed. Men, boys. What kind of a people is that?”

“You tell me,” I say.

“Animals,” Callisthenes says. He’s looking me in the eye, not smiling. A rare passion from such a mild creature.

“And what separates man from the animals?”

“Reason. Work. The life of the mind.”

“Out again tonight?” I ask.

THE NEXT MORNING I return to Arrhidaeus in his room. His face is tear-stained and snot-crusted; his nurse gazes out a window and pretends not to hear me enter. The boy himself smiles, sweet and frail, when he sees me. I wish him good morning and he says, “Uh.”

“Any progress?” I ask the nurse.

“In one day?”

I help myself to a cloak hanging on the back of a chair, which I drape over the boy’s shoulders. “Where are your shoes?”

The nurse is watching now. He’s a prissy little shit, and sees his moment.

“He can’t walk far,” he says. “He doesn’t have winter shoes, just sandals. He never goes outdoors, really.”

“Then we’ll have to borrow yours,” I tell him.

Eyebrows up, “And what will I wear?”

“You can wear Arrhidaeus’s sandals since you won’t be coming.”

“I’m obliged to accompany him everywhere.”

I can’t tell if he’s angry with me or frightened of being caught away from his charge. He glances at Arrhidaeus and reaches automatically to wipe the hair from the boy’s face. Arrhidaeus flinches from his touch. So, they’ve had that kind of morning.

“Give me your fucking shoes,” I say.

Arrhidaeus wants to take my hand as we walk. “No, Arrhidaeus,” I tell him. “Children hold hands. Men walk by themselves, you see?”

He cries a little, but stops when he sees where I’m leading him. He gibbers something I can’t make out.

“That’s right,” I say. “We’ll take a walk into town, shall we?”

He laughs and points at everything: the soldiers, the gate, the grey swirl of the sky. The soldiers look interested, but no one stops us. I wonder how often he leaves his room, and if they even know who he is.

“Where is your favourite place to go?”

He doesn’t understand. But when he sees a horse, a big stallion led through the gate, he claps his hands and gibbers some more.

“Horses? You like horses?”

Through the gate I’ve caught a glimpse of the town—people, horses, the monstrous houses that so offended my nephew—and I realize my heart’s not ready for it, so I’m happy enough to lead him back to the stables. In the middle of a long row of stalls I find our animals, Tweak and Tar and Lady and Gem and the others. Arrhidaeus is painfully excited and when he stumbles into me I wonder from the smell if he’s pissed himself. The other horses look sidelong, and only big black Tar takes much of an interest in us, lifting his head when he recognizes me and ambling over for some affection. I show Arrhidaeus how to offer him a carrot from his open hand, but when the horse touches him, he shrieks and flinches away. I take his hand and guide it back, getting him to stroke the blaze on Tar’s forehead. He wants to use his knuckles, and when I look closely I see his palm is scored with open sores, some kind of rash. I’ll have to find him an ointment.

“Do you ride?” I ask him.

“No, sir,” someone calls. It’s a groom who’s been mucking out the straw. “That other one brings him here sometimes and lets him sit in a corner. He’ll sit quiet for hours that way. He hasn’t got the balance for riding, though. Doesn’t need another fall on the head, does he?”

I lead Tar out into the yard and saddle him. It’s raining again. I get Arrhidaeus’s foot in my cupped hands and then he’s stuck. He’s stopped laughing, at least, and looks at me for help. I try to give him a boost up, but he’s too weak to heft himself over the horse’s back. He hops a little on one foot with the other cocked up in the air, giving me a view of his wet crotch.

“Here,” the groom says, and rolls over a barrel for the boy to stand on.

Between the two of us we get him up alongside the horse and persuade him to throw a leg over the animal’s back.

“Now you hug him,” the groom says, and leans forward with his arms curved around an imaginary mount. Arrhidaeus collapses eagerly onto Tar’s back and hugs him hard. I try to get him to sit back up, but the groom says, “No, no. Let the animal walk a bit and get him used to the movement.”

I lead Tar slowly around the yard while Arrhidaeus clings to him full-body, his face buried in the mane. The groom watches.

“Is he a good horse?” he calls to Arrhidaeus.

The boy smiles, eyes closed. He’s in bliss.

“Look at that, now,” the groom says. “Poor brained bastard. Did he piss himself?”

I nod.

“There, now.” He leads Tar back to the barrel and helps Arrhidaeus back down. I had expected the boy to resist but he seems too stunned to do anything but what he’s told.

“Would you like to come back here?” I ask him. “Learn to ride properly, like a man?” He claps his hands. “When are we least in the way?” I ask the groom.

He waves the question away. His black eyes are bright and curious, assessing, now Tar, now Arrhidaeus. “I don’t know you,” he says, without looking at me properly. He slaps Tar fondly on the neck.

“I’m the prince’s physician.” I rest a hand on Arrhidaeus’s shoulder. “And his tutor. Just for a few days.”

The groom laughs, but not so that I dislike him for it.

EURIPIDES WROTE THEBacchae at the end of his life. He left Athens disgusted by his plays’ losses at the competitions, so the story goes, and accepted an invitation from King Archelaus to come to Pella and work for a more appreciative (less discriminating) audience. He died that winter from the cold.

Plot: Angry that his godhead is denied by the Theban royal house, Dionysus decides to take his revenge on the priggish young King Pentheus. Pentheus has Dionysus imprisoned. The god, in turn, offers to help him spy on the revels of his female followers, the Bacchantes. Pentheus, both fascinated and repulsed by the wild behaviour of these women, agrees to allow himself to be disguised as one of them to infiltrate their revels on Mount Kithairon. The disguise fails, and Pentheus is ripped to pieces by the Bacchantes, including his own mother, Agave. She returns to Thebes with his head, believing she has killed a mountain lion, and only slowly recovers from her possessed state to realize what she’s done. The royal family is destroyed, killed or exiled by the god. The play took first prize at the competition in Athens the following year, after Euripides’ death.

We all love the Bacchae.

The actors huddle together downstage, except for the man playing the god, who stands on an apple crate so he can look down on the mortals. He’s not very tall. For the performance they could dress him in a robe long enough to hide the crate. That’s a good idea.

“Pentheus, my son … my baby … ” the actor playing Agave says. “You lay in my arms so often, so helpless, and now again you need my loving care. My dear, sweet child … I killed you—No! I will not say that, I was not there!” an actor says. “I was … in some other place. It was Dionysus. Dionysus took me, Dionysus used me, and Dionysus murdered you.”

“No,” the actor playing the god replies. “Accept the guilt, accuse yourselves.”

“Dionysus, listen to us,” the actor playing Agave’s father, Kadmos, says. “We have been wrong.”

After a moment’s hesitation, the director calls, “Now you understand.”

“Now you understand, but now is too late. When you should have seen, you were blind,” the actor playing the god says.

“We know that. But you are like a tide that turns and drowns us.”

“Because I was born with dominion over you and you dispossessed me. And I don’t—”

The director interrupts, calling, “Kadmos!”

“Then you should not be like us, your subjects. You should have no passions,” the old man upstage says reprovingly.

“And I don’t,” the actor repeats, and when no one interrupts him continues. “But these are the laws, the—the laws of life. I cannot change them.”

“The laws of life,” the director calls.

“The laws of life,” the actor repeats.

“It is decided, Father,” the actor playing the woman, Agave, says. “We must go, and take our grief with us.”

There’s some business with a sheet of cloth, allowing the actor playing Dionysus to slip offstage, unseen by the audience, leaving the crate behind. I amend my idea to stilts.

When the actor playing Agave takes a deep breath and says nothing, the director calls, “Help me. Take me to my sisters. They will share my exile and the years of sorrow. Take me where I cannot see Mount Kithairon, where branches wound with ivy cannot remind me of what has happened. Let someone else be possessed. I have withered. Fuck me, but I have withered.”

Afterwards, over wine backstage, the director shakes his head and says, “Amateurs.”

“You won’t get professionals here,” I say.

He’s an Athenian, this Carolus, with a drinker’s genial blob of a nose and a husky, hectoring way of running the world. The actor playing the woman, Agave, at a livelier table across the room, makes a leggy chestnut mare.

“That one looks the part, at least,” I say.

“He does indeed,” Carolus says. “That may have been my mistake.”

At the actors’ table there’s much merry jostling of chairs to make room for me, though I refuse to sit down. They’re still in their costumes and are enjoying themselves voraciously.

“Better every time,” I say.