1,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 0,99 €

Niedrigster Preis in 30 Tagen: 0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Booksell-Verlag

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

In "The History of Don Quixote de la Mancha," Miguel de Cervantes deftly weaves a rich tapestry of satire and adventure, exploring the nature of reality and illusion through the misadventures of its titular character, an aging gentleman who becomes enamored with the chivalric ideals of knighthood. Written in the early 17th century, this monumental work employs a distinctive blend of prose and dialogue, showcasing Cervantes' innovative narrative techniques, such as the use of unreliable narration and metafiction. The novel is not merely a comedy; it is a profound commentary on human ambition, delusion, and the power of imagination within a growing modern world, poised at the cusp of the Enlightenment. Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra, often heralded as the father of the modern novel, drew from his tumultuous life experiences, including military service, imprisonment, and financial hardships. These challenges imbued him with deep insights into the human condition, which resonate powerfully in "Don Quixote". Cervantes' own encounters with societal norms and his critique of contemporary literature underscored the novel's enduring relevance and inventiveness. Readers seeking a blend of humor, philosophy, and social commentary will find "The History of Don Quixote de la Mancha" an indispensable addition to their literary repertoire. This timeless work challenges our perceptions, inviting reflection on the thin line between sanity and madness, inviting us to embrace our quests for meaning in a complex world. In this enriched edition, we have carefully created added value for your reading experience: - A succinct Introduction situates the work's timeless appeal and themes. - The Synopsis outlines the central plot, highlighting key developments without spoiling critical twists. - A detailed Historical Context immerses you in the era's events and influences that shaped the writing. - An Author Biography reveals milestones in the author's life, illuminating the personal insights behind the text. - A thorough Analysis dissects symbols, motifs, and character arcs to unearth underlying meanings. - Reflection questions prompt you to engage personally with the work's messages, connecting them to modern life. - Hand‐picked Memorable Quotes shine a spotlight on moments of literary brilliance. - Interactive footnotes clarify unusual references, historical allusions, and archaic phrases for an effortless, more informed read.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

The History of Don Quixote de la Mancha

Table of Contents

Introduction

"When life itself seems lunatic, who knows where madness lies?" This hauntingly profound quote from Miguel de Cervantes's iconic Don Quixote encapsulates the essence of the novel's exploration of perception and reality. It invites readers to ponder the thin line between sanity and folly, setting the stage for a narrative that ventures deeply into the human psyche and the world around us. Presenting the heart of a man who beliefs turn him into a knight-errant, this delves into the whimsical nature of dreams in contrast with mundane existence, reflecting the complexities of the human condition that resonates throughout the ages.

Widely celebrated as a cornerstone of Western literature, Don Quixote is recognized not only for its enduring narrative but also for its transformative impact on the art of storytelling. By blending genres and defying traditional structures, Cervantes introduced innovative techniques that would later inspire countless writers, from contemporaries to modern literary giants. Its rich tapestry of themes—from idealism clashing with realism to the nuances of personal identity—has made it an indispensable text in the literary canon, revered for its profound insights into the human experience.

Written between 1605 and 1615, Don Quixote emerges from a period when literature underwent significant evolution, shifting from medieval to early modern themes. Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra, a soldier, prisoner, and creative genius, crafted this seminal work in response to the rapidly changing cultural landscape of Spain. The book unfolds through the adventures of a delusional nobleman who, convinced he is a knight destined to revive chivalry, departs on a quest for honor and glory. Cervantes's intention was not only to entertain but to create a mirror reflecting society's follies and aspirations, exploring both humor and poignancy in human motivation.

As readers delve into the pages of Don Quixote, they are introduced to a host of memorable characters, most notably Sancho Panza, who serves as both a foil and companion to the protagonist. The interactions between the idealistic Quixote and the pragmatic Panza allow Cervantes to examine the delicate balance between lofty dreams and harsh realities. Through these two, the narrative elevates the exploration of friendship and loyalty while simultaneously critiquing the values of contemporary society, providing a dual lens that invites reflection on one’s own ideals and actions.

Cervantes’s writing style is rich and layered, seamlessly weaving humor, poignancy, and biting satire throughout the chapters of Don Quixote. The author deftly employs various narrative techniques, including metafictional elements that draw attention to the act of storytelling itself. This self-referential aspect not only enriches the reading experience but also paves the way for future authors to experiment with narrative forms. Cervantes invites readers into the playful dance of fiction, blurring the boundaries between reality and imagination.

The themes of madness and sanity find particular resonance in Don Quixote, compelling readers to assess their own perceptions of reality. Quixote's grand delusions challenge the norms of his society, prompting a commentary on the fragility of sanity in a world riddled with contradictions. This exploration of mental states opens the door to discussions on the nature of belief, the quest for meaning, and the potential for self-deception. It is a reflection on how one man’s pursuit of a noble cause can be both a source of strength and a path to folly.

Central to Don Quixote is the theme of idealism clashing with realism, which resonates deeply in our modern age. This tension is exemplified through Quixote's persistent pursuit of adventures that embody the values of a bygone era, juxtaposed against the often harsh realities of the world. Here, Cervantes deftly illustrates the struggle inherent in navigating one's aspirations amidst societal indifference and practical constraints. This enduring theme speaks to the universal challenge of reconciling dreams with the starkness of everyday life, making it relevant across generations.

Furthermore, the motif of transformation culminates in Don Quixote’s deeply personal journey, where the boundary between fantasy and reality becomes increasingly blurred. As Quixote engages with various characters, he leaves an indelible mark on their lives, leading them to question their own realities. This aspect of the narrative emphasizes the power of influence and the importance of personal ties, suggesting that the ideals we pursue can shape not only our own destinies but also those of others. Cervantes presents a compelling case for the communal nature of human experience, underscoring the ripple effects of our actions.

Cervantes’s keen observations on human nature extend beyond the characters of Don Quixote; they resonate with anyone grappling with existential questions. The bittersweet humor woven through the narrative presents a compassionate view of humanity’s follies. Even as Quixote chases after his dreams with unwavering zeal, readers cannot help but reflect on their own aspirations, failures, and those small victories that color the human experience. Cervantes builds a connection with his audience, ensuring that they, too, engage with the questions that arise from Quixote's exploits.

The legacy of Don Quixote reaches far beyond the confines of its pages; it has left an indelible mark on literature and popular culture alike. Adaptations in various art forms—from theatrical productions to film adaptations—demonstrate the timeless nature of its core themes and characters. Each reinterpretation offers fresh perspectives on Quixote’s journey, affirming the novel's adaptability and relevance in diverse contexts. Such ongoing engagement with the text ensures that new generations continue to explore its rich tapestry, perpetuating the cycle of reflection and appreciation that Cervantes envisioned.

Moreover, the exploration of identity within Don Quixote raises compelling questions regarding self-perception and societal roles. As Quixote plays the role of the knight-errant, he forces those around him to grapple with their own identities, challenging conventions and prompting reexamination of societal norms. Cervantes deftly navigates the fluidity of identity, illustrating how individuals can embody various roles throughout their lives. This complexity renders the narrative accessible and relatable, transcending its historical setting to speak to a contemporary audience.

As decades and centuries have passed since Don Quixote first appeared, its themes of resilience and the invincible spirit continue to shine through. The character of Quixote serves as an archetype for the dreamers and visionaries who populate our world—those who dare to pursue their dreams despite formidable odds and societal skepticism. This enduring capacity for hope resonates universally and encourages readers to contemplate the passions that drive them, igniting discussions on ambition, valor, and the human spirit’s indomitable nature.

In addition to resonating with themes of madness and idealism, Don Quixote invites conversations around the nature of truth and deception. Cervantes grapples with the multifaceted nature of truth, particularly in a world filled with competing narratives and subjective experiences. Quixote’s journey raises fundamental questions about the reliability of perception and the subjective lenses through which we view life. In both humorous and poignant terms, the narrative invites readers to consider what constitutes truth in a world rife with illusions.

An exploration of friendship emerges as another key theme within Don Quixote, encapsulated in the dynamic between Quixote and Sancho Panza. Their relationship exemplifies loyalty, camaraderie, and the complexities inherent in companionship. Together, they embark on a journey that reflects both their differences and shared aspirations, forging a bond that serves as a source of strength and understanding. Cervantes underscores the importance of these connections, shedding light on how profound relationships can enrich our lives and narratives while navigating the trials of existence.

Conclusively, Don Quixote de la Mancha remains a timeless examination of human aspirations, clarity, folly, and loyalty grounded in the mundane intricacies of life. Cervantes’s artful storytelling embodies universal questions that transcend historical and cultural contexts, allowing readers to connect with their innermost reflections on existence. Its richly layered themes challenge individuals to confront their beliefs while inspiring them to pursue their ideals amidst the chaos of reality. This resonance makes the work not merely a narrative but a multifaceted exploration of humanity that appeals to both our hearts and our minds.

As readers embark on this journey through Don Quixote, they are invited to engage in reflection and self-discovery. The text encourages contemplation of aspirations, identity, and the nature of dreams, allowing individuals to find their own interpretations, revelations, and connections to its myriad themes. This active engagement fosters a dialogue between the text and the reader, strengthening the book’s relevance and ensuring a shared understanding of the human experience, illuminating how dreams and reality, humor and tragedy coexist in our lives.

In a world often defined by disillusionment and complexity, the exploration of idealism within Don Quixote serves as a balm for the modern spirit. It reaffirms the endurance of dreams and the nobility of heartfelt pursuits, urging readers to cherish their aspirations while navigating life’s uncertainties. Ultimately, Cervantes’s timeless masterpiece transcends its historical context, continuing to inspire and challenge readers of all ages. Its lasting appeal is a testament to the power of storytelling and the profound exploration of humanity’s endless quest for meaning.

Synopsis

The History of Don Quixote de la Mancha, authored by Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra, narrates the adventures of an aging nobleman, Alonso Quixano, who becomes enamored with chivalric romances. This obsession leads him to adopt the persona of 'Don Quixote' and embark on a quest to revive chivalry, seeking to become a knight-errant. His heroic aspirations are accompanied by a profound disconnect from reality, leading him to see ordinary objects and people as larger-than-life figures, consequently setting the foundation for a rich exploration of themes such as illusion versus reality and the nature of heroism.

The novel unfolds as Don Quixote dons an old suit of armor and sets off on his trusty steed, Rocinante, determined to right wrongs and defend the helpless. Accompanying him on his journeys is Sancho Panza, a simple farmer who becomes his loyal squire. Sancho offers a counterbalance to Don Quixote’s lofty ideals with his practical wisdom and earthy humor. Their disparate personalities and worldviews result in humorous and poignant interactions, showcasing the complexities of human nature and friendship. Together, they face a series of misadventures that challenge their perceptions and aspirations.

As Don Quixote travels through the Spanish countryside, he encounters various characters who challenge his intentions and beliefs. From windmills that he perceives as fearsome giants to a group of actors whom he mistakes for real knights, each episode reflects the tension between his grandiose dreams and the often mundane realities of life. These encounters serve to highlight the pervasive theme of illusion versus reality, as Don Quixote's idealism frequently clashes with the practical mindset of those around him, particularly Sancho Panza.

Throughout the narrative, Cervantes delves into the psychological motivations of his characters, especially focusing on Don Quixote’s fervent desire to live within the chivalric ideals he admires. Sancho, who often expresses skepticism, represents a grounded perspective that contrasts with Quixote's romantic notions. Their interactions illustrate the philosophical debates on reality, perception, and the meaning of heroism. Cervantes uses humor and satire to critique societal norms, revealing the absurdities of a world that values superficial appearances over genuine virtue.

Key events in the novel include Don Quixote’s ill-fated battles, such as his famous confrontation with the windmills, which symbolize the futility of fighting against the inexorable forces of reality. Additionally, his misinterpretation of various social situations, like the barber’s basin he believes to be a legendary helmet, further accentuates his delusions. These moments contribute to the overarching narrative while illustrating the larger questions regarding the nature of sanity, valor, and the individual’s place in society, ultimately underscoring the absurdity of his quest.

As the story progresses, Don Quixote's adventures lead him to various towns and villages, where his reputation grows—both as a madman and a hero. His eccentric behavior elicits a mix of admiration and ridicule from those he encounters. Alongside this grow themes of transformation as characters influenced by Quixote’s noble aspiration begin to reflect on their own lives and values. This ripple effect extends beyond the principal characters, prompting readers to reflect on the nature of heroism and the quest for meaning in a seemingly indifferent world.

In the latter part of the novel, Don Quixote faces increasing opposition and the consequences of his misguided quests. The villagers, frustrated with his antics, seek to bring him back to reality. Sancho Panza begins to realize the limits of Quixote’s vision, yet struggles with steadfast loyalty to his master. This tension serves as a turning point, exploring deeper themes of loyalty and the bonds between dreamers and pragmatists. Cervantes utilizes these developments to underscore the vulnerabilities inherent in human aspirations and the resulting themes of sacrifice and devotion.

Ultimately, Don Quixote’s trajectory leads him back to his home, where he confronts the realities of his actions. In a moment of clarity, he begins to understand the consequences of his delusions and the fleeting nature of his chivalric dreams. Cervantes crafts a poignant conclusion where Quixote renounces his delusions and acknowledges the importance of reconnecting with reality. This shift invites readers to ponder the balance between imagination and practicality and the importance of self-awareness amid life’s struggles.

The History of Don Quixote de la Mancha stands as a profound exploration of the human condition, emphasizing the complexities of ambition, idealism, and the nature of true heroism. Cervantes invites readers to reflect on the interplay of dreams and reality, conveying that the pursuit of noble ideals, while often misguided, can reveal deeper truths about human existence. Through the lens of comedy and tragedy, the narrative encourages an appreciation for both the aspirations that drive us and the harsh realities we must ultimately confront.

Historical Context

Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra's novel "Don Quixote de la Mancha" is set in the early 17th century, mainly in the regions of La Mancha and Aragon in central and eastern Spain. During this period, Spain was a dominant empire under the Habsburg dynasty with extensive territories across Europe, the Americas, Asia, and Africa. However, despite this vast empire, Spain was facing internal challenges such as financial difficulties and a decline in political influence. The era was marked by a transition from the Renaissance to the Baroque, distinguished by social stratification and a rigid class system, coupled with economic disparities between the aristocracy and the peasantry. Cervantes situates his narrative in this time of socio-political upheaval, capturing the tensions between the fading ideals of chivalry and the onset of modernity.

Although the Reconquista concluded in 1492 with the Catholic Monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella capturing Granada from Muslim rule, it provided a backdrop of religious and cultural identity rooted in Christian values that influenced Spanish national consciousness. Cervantes’ exploration of chivalric ideals through the character of Don Quixote can be viewed as reflecting the tension between outdated knightly valor and the more secular society emerging in his time.

The Spanish Inquisition, established in 1478 to enforce Catholic orthodoxy, formed part of the backdrop of Cervantes’ life, creating an atmosphere of censorship and conformity. While "Don Quixote" does not directly mention the Inquisition, Cervantes’ satirical treatment of religious and social norms may suggest a critique of the era's rigidity and intolerance, hinting at the perils of expressing dissenting views.

Another significant historical context is the Eighty Years' War (1568-1648) between Spain and the Dutch Republic. This prolonged conflict drained Spain’s resources and challenged the Habsburg monarchy, reflected in the economic hardships portrayed in the novel. Cervantes subtly explores these tensions through the struggles faced by his characters, contrasting the grandiose ideas of empire with the realities confronting common people.

Cervantes' participation in the Battle of Lepanto in 1571, a crucial naval engagement against the Ottoman Empire, where he was injured, underscores his personal experiences with war. His subsequent capture by Barbary pirates further informed his depictions of heroism and suffering, blending romanticized chivalry with war's brutal reality.

Spain's decline during the early 17th century, after its Golden Age in the arts and warfare, mirrors the themes in Cervantes' work. Political instability and economic difficulties, exacerbated by expensive wars and empire maintenance, echo in Don Quixote’s quixotic adventures, symbolizing the impracticality of clinging to outdated ideals in a changing world.

The annexation of Portugal in 1580, which lasted until 1640 under the Iberian Union, expanded Spain's influence but strained its resources. This tension is mirrored in the novel's depiction of Don Quixote's unrealistic quests, highlighting the impracticality of ambition when confronting practical limitations.

The Counter-Reformation, a Catholic movement to counter the Protestant Reformation, strengthened orthodoxy and reinforced papal authority, leading to increased censorship in Spain. This backdrop resonates with themes in the novel, as Cervantes critiques unexamined adherence to outdated ideals through the misadventures of his protagonist.

The reform efforts by Philip II and Philip III to centralize power and normalize religious uniformity shaped the setting and themes explored by Cervantes. He critiques these rigid bureaucratic and religious controls through his depiction of various institutions and characters, paralleling Don Quixote’s adherence to chivalric codes with society's outdated systems.

The failed Spanish Armada in 1588, an attempted invasion of England, symbolized the decline of Spain’s naval power. "Don Quixote" parallels this with the protagonist’s misguided quests, reflecting on the decline of national pride and power, using satire to critique unrealistic ambitions.

Spain's social stratification and economic divide exacerbated class struggles despite the empire's grandeur. Cervantes highlights these disparities through the contrasting lives of Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, offering a satirical examination of class divides and critiquing the romanticized notion of social nobility amid growing inequality.

The rural depopulation and poverty in regions like Castile, affected by noble absenteeism and the Moriscos' expulsion in 1609, weighed down Spain's economy. These themes are illustrated in Don Quixote’s landscape, where the protagonist’s ideals clash with an economically and morally depleted society.

The satirical elements in Don Quixote connect with broader European intellectual transitions during the Renaissance. Cervantes’ critique of chivalric traditions exemplifies the shift toward valuing rationality, realism, and empirical analysis over dogma, reflecting the era’s cultural reimagination and the burgeoning modern novel.

Cervantes captures the challenges of urban growth, associated with early modern city migration, within the episodic structure of "Don Quixote," portraying rural and urban dynamics. This reflects the tensions between traditional practices and modern urban realities.

Spain’s Golden Age was a time of cultural renaissance, influencing Cervantes along with contemporaries like Lope de Vega and El Greco. His novel critiques and expands literary traditions, blending humor with complex narratives that question perception and reality, heralding the development of modern literary forms.

"Don Quixote" critiques its historical period by illustrating societal contradictions at the brink of modernity, challenging outdated institutions and social structures. Through satire, Cervantes exposes the absurdity of rigid class divides and societal inertia, encouraging readers to reflect on the necessity of adapting to change. The tragicomic misadventures of Don Quixote symbolize the human condition, as noble intentions are often thwarted by systemic failings and resistance to reform.

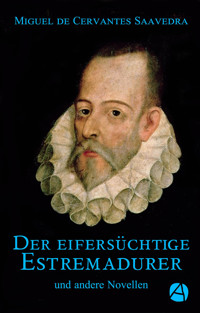

Author Biography

Introduction

Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra (1547–1616) is widely regarded as the preeminent figure of Spanish letters and a foundational voice in world literature. Born in Alcalá de Henares and active through the tumultuous late Renaissance, he combined the experiences of soldier, captive, bureaucrat, and writer into a body of work marked by irony, empathy, and formal daring. His Don Quixote—published in two parts in the early 1600s—reshaped narrative art and is often hailed as the first modern novel. Alongside that masterpiece, he authored La Galatea, the Novelas ejemplares, innovative plays and interludes, and the posthumous romance Persiles, securing a lasting, global legacy.

Education and Literary Influences

Miguel de Cervantes was baptized in 1547; details of his early schooling are sparse. As a young man he lived in Madrid, where he studied under the humanist Juan López de Hoyos in the 1560s. López de Hoyos printed several of Cervantes’s early poems in memorial volumes, praising him as a dear pupil, evidence of an education grounded in rhetoric, Latin authors, and civic eloquence. Before turning fully to literature, Cervantes spent time in Italy, absorbing the artistic and intellectual ferment of Rome and other centers. This mixture of humanist schooling and cosmopolitan exposure shaped the language, humor, and ethical concerns of his later prose.

His influences reflected the breadth of reading available in late Renaissance Spain. He engaged critically with the chivalric romances that had enthralled generations, transforming their conventions into instruments of satire and compassion. His pastoral debut, La Galatea, drew on Iberian and Italian models of Arcadian fiction, while the Novelas ejemplares dialogued with the picaresque tradition then flourishing. Time in Italy broadened his horizons: poets such as Ariosto and Tasso, and the vernacular refinements of the Italian Renaissance, informed his style and narrative architecture. Classical satire and the dialogic techniques of humanist prose also contributed to his distinctive blend of realism and metafiction.

Literary Career

La Galatea appeared in the mid-1580s, announcing Cervantes’s arrival as a novelist with a pastoral romance that interlaced lyric digressions and tales of unrequited love. Around the same period, he sought success in the theater, composing comedias and short interludes. The rapid ascent of Lope de Vega’s “new art” of drama, however, limited Cervantes’s stage fortunes, and many early plays are lost. He supported himself through administrative posts, experiences that furnished acute observations of social types and institutions. Despite intermittent recognition, he remained, for decades, a writer of promise more than fame, continuing to experiment across genres while refining the voice that would define him.

In the early 1600s, Cervantes published the first part of Don Quixote, a work conceived as a response to—and meditation on—the culture of chivalric romance. The novel’s aging hidalgo, self-fashioned as a knight-errant, and his practical squire, Sancho Panza, travel through a vividly rendered Spain, confronting illusions and realities in tandem. Cervantes deployed multiple narrators, a mock-scholarly frame, and self-aware commentary to question authority, textuality, and truth. The book met immediate popular success, was quickly reprinted, and soon translated, making its author internationally known. Readers praised its humor and novelty, while discerning critics noted its philosophical depth and narrative ingenuity.

Success enabled Cervantes to publish the Novelas ejemplares, a collection of short prose fictions that display striking variety in tone and form. From the comic underworld of Rinconete y Cortadillo to the unsettling irony of El celoso extremeño and the talking-dogs colloquy of El coloquio de los perros, he explored moral choice, social mobility, and the fallibility of perception. The “exemplary” promise of edification coexists with ambiguity, inviting readers to weigh competing interpretations. The collection consolidated his reputation as an experimenter who could compress life into concentrated narrative scenes, sustaining ethical reflection without relinquishing entertainment, wit, or stylistic elegance.

Turning again to poetry and theater, Cervantes issued Viaje del Parnaso, a satirical poem on poets and poetics, and Ocho comedias y ocho entremeses nuevos, never before performed, which preserved his dramatic art in print. The interludes, in particular—such as El juez de los divorcios and El retablo de las maravillas—balance farce with social critique, offering compact stages where language and deception collide. While he did not displace contemporary theatrical fashions, these works showed his resilient versatility. He used the prologues to articulate views on literary craft, originality, and audience, situating himself within, and sometimes against, the dominant trends of his day.

The unauthorized continuation of Don Quixote under the name of “Avellaneda,” printed in the mid-1610s, prompted Cervantes to accelerate and sharpen his own second part. Published soon after, Part II deepens the psychological interplay between knight and squire, amplifies the book’s reflection on fame and impersonation, and renders its characters aware of their earlier adventures’ publication. The result is a more bittersweet, formally reflexive narrative that tests ideals against social performance. Together, the two parts form a singular investigation of imagination, friendship, and identity, sealing Cervantes’s standing among his contemporaries and preparing the ground for his final long fiction.

Beliefs and Advocacy

Although not a polemicist, Cervantes conveyed recognizable convictions throughout his works. He distrusted dogmatism and extremes, favoring prudence, charity, and the examined life. His satire targets vanity, credulity, and institutional abuses without lapsing into nihilism; the dignity of individuals, however humble, remains central. Don Quixote probes the responsibilities of readers and writers, insisting on discernment and ethical imagination. The Novelas ejemplares examine justice and mercy in everyday contexts, exposing the costs of rigid honor codes. Across genres, he defends conversation, reason, and compassion as means to navigate error, aligning literary pleasure with moral inquiry in a distinctly humanist key.

Cervantes’s life informed this outlook. A veteran of Lepanto who endured years of captivity in Algiers and later bureaucratic hardships, he wrote with unusual sympathy for captives, migrants, and the poor. The Captive’s Tale in Don Quixote and the figure of Ricote, a Morisco, acknowledge the era’s conflicts while registering complex loyalties and losses. His depictions of legal officials, soldiers, and clergy vary from satirical to respectful, resisting caricature and insisting on individual motives. In public prefaces and authorial asides, he argued for creative integrity and resisted misattribution, shaping an ethic of authorship that valued honesty of representation over facile applause.

Final Years & Legacy

In his final years, Cervantes lived mainly in Madrid and enjoyed the encouragement of patrons interested in his late projects. He completed Los trabajos de Persiles y Sigismunda, a Byzantine-style romance that reimagines pilgrimage and identity through adventurous plotting and moral testing; it appeared shortly after his death. Aware of his stature and of his mortality, he worked with urgency, composing dedications that reflect gratitude and resolve. He died in 1616 in Madrid and was buried in the city. Contemporary readers recognized his achievement, even as the theater dominated public taste, and his name remained closely tied to Don Quixote.

Over the centuries, Cervantes’s reputation has grown steadily, his novel read as a pioneering exploration of modern subjectivity, narrative self-consciousness, and social reality. Don Quixote and Sancho Panza became cultural archetypes, emblematic of idealism and pragmatism in dialogue. Writers from Fielding and Sterne to Flaubert, Dostoevsky, Kafka, and Borges acknowledged debts to his art, and his influence persists across languages and media. Academic study continues to illuminate his craft and context, while major institutions—such as the Instituto Cervantes and the Spanish-language Cervantes Prize—commemorate his legacy. Today he stands as a touchstone of literary imagination, humor, and ethical complexity.

The History of Don Quixote de la Mancha

Preface.

When we reflect upon the great celebrity of the "Life, Exploits, and Adventures of that ingenious Gentleman, Don Quixote de la Mancha," and how his name has become quite proverbial amongst us, it seems strange that so little should be known concerning the great man to whose imagination we are indebted for so amusing and instructive a tale. We cannot better introduce our present edition than by a short sketch of his life, adding a few remarks on the work itself and the present adapted reprint of it.

The obscurity we have alluded to is one which Cervantes shares with many others, some of them the most illustrious authors which the world ever produced. Homer, Hesiod,—names with which the mouths of men have been familiar for centuries,—how little is now known of them! And not only so, but how little was known of them even by those who lived comparatively close upon their own time! How scattered and unsatisfactory are the few particulars which we have of the life of our own poet William Shakspere!

Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra was born at Alcala de Henares, a town of New Castile, famous for its University, founded by Cardinal Ximenes. He was of gentle birth, both on his father's and mother's side. Rodrigo de Cervantes, his father, was descended from an ancient family of Galicia, of which several branches were settled in some of the principal cities of Spain. His mother's name was Leonora de Cortēnas. We find by the parish register of Santa Maria la Mayor, at Alcala de Henares, that Miguel was baptised in that church on Sunday, the 9th of October, 1547; in which year we may conclude, therefore, that he was born. The discovery of this baptismal register set at rest a dispute which had for some time been going on between seven different cities, each of which claimed the honour of being the native place of our author: these were, besides the one already mentioned, Seville, Madrid, Esquivias, Toledo, Lucena, and Alcazar de San Juan. In this respect we cannot avoid drawing a comparison between the fame of Cervantes and the prince of poets, Homer.

From a child he discovered a great liking for books, which no doubt determined his parents, whose fortune, notwithstanding their good family, was any thing but affluent, to educate him for one of the learned professions, by which alone at that time there was any chance of getting wealth. Miguel, however, did not take to the strict studies proposed to him: not that he was idle; his days were spent in reading books of amusement, such as novels, romances, and poems. It was of the materials afforded by such a pursuit that his fame was afterwards built.

Cervantes continued at Madrid till he was in his twenty-first year, during which time he remained with his learned tutor Juan Lopez de Hoyos. He seems to have been a great favourite with him; for, in a collection of "Luctus," published by Juan on the death of the Queen, we find an elegy and a ballad contributed by the editor's "dear and beloved disciple Miguel de Cervantes." Under the same editorial care Cervantes himself tells us, in his Viage de Parnasso, that he published a pastoral poem of some length, called 'Filena,' besides several ballads, sonnets, canzonets, and other small poems.

Notwithstanding the comparative insignificance of these productions, they probably excited some little attention; for it appears not unlikely that it was to them that Cervantes owed his appointment to an office, which we find him holding, in 1569, at Rome,—that of chamberlain to his eminence the Cardinal Julio Aquaviva, an ecclesiastic of considerable learning. Such an appointment, however, did not suit the active disposition and romantic turn of one so deeply read in the adventures of the old knights, the glory of which he longed to share; from which hope, however, the inactivity and monotony of a court-life could not but exclude him.

In 1571 there was concluded a famous league between Pope Pius V., Philip II. of Spain, and the Venetian Republic, against Selim, the Grand Turk, who was attacking Cyprus, then belonging to Venice. John of Austria, natural son of the celebrated Emperor Charles V., and brother of the king of Spain, was made commander-in-chief of the allied forces, both naval and military; and under him, as general of the Papal forces, was appointed Mario Antonio Colonna, Duke of Paliano. It became fashionable for the young men of the time to enlist in this expedition; and Cervantes, then about twenty-four years of age, soon enrolled himself under the standard of the Roman general. After various success on both sides, in which the operations of the Christians were not a little hindered by the dissensions of their commanders, to which the taking of Nicosia by the Turks may be imputed, the first year's cruise ended with the famous battle of Lepanto[1]; after which the allied forces retired, and wintered at Messina.

Cervantes was present at this famous victory, where he was wounded in the left hand by a blow from a scymitar, or, as some assert, by a gunshot, so severely, that he was obliged to have it amputated at the wrist whilst in the hospital at Messina; but the operation was so unskilfully performed, that he lost the use of the entire arm ever afterwards. He was not discouraged by this wound, nor induced to give up his profession as a soldier. Indeed, he seems, from his own words, to be very proud of the honour which his loss conferred upon him. "My wound," he says, "was received on the most glorious occasion that any age, past or present, ever saw, or that the future can ever hope to see. To those who barely behold them, indeed, my wounds may not seem honourable; it is by those who know how I came by them that they will be rightly esteemed. Better is it for a soldier to die in battle than to save his life by running away.[1q] For my part I had rather be again present, were it possible, in that famous battle, than whole and sound without sharing ill the glory of it. The scars which a soldier exhibits in his breast and face are stars to guide others to the haven of honour and the love of just praise."

The year following the victory of Lepanto, Cervantes still continued with the same fleet, and took part in several attacks on the coast of the Morea. At the end of 1572, when the allied forces were disbanded, Colonna returned to Rome, whither our author probably accompanied him, since he tells us that he followed his "conquering banners." He afterwards enlisted in the Neapolitan army of the king of Spain, in which he remained for three years, though without rising above the rank of a private soldier; but it must be remembered that, at the time of which we are now speaking, such was the condition of some of the noblest men of their country; it was accounted no disgrace for even a scion of the nobility to fight as a simple halberdier, or musqueteer, in the service of his prince.

On the 26th of September, 1575, Cervantes embarked on board a galley, called the 'Sun,' and was sailing from Naples to Spain, when his ship was attacked by some Moorish corsairs[2], and both he and all the rest of the crew were taken prisoners, and carried off to Algiers. When the Christians were divided amongst their captors, he fell to the lot of the captain, the famous Arnauté Mami, an Albanian renegade, whose atrocious cruelties are too disgusting to be mentioned. He seems to have treated his captive with peculiar harshness, perhaps hoping that by so doing he might render him the more impatient of his servitude, and so induce him to pay a higher ransom, which the rank and condition of his friends in Europe appeared to promise. In this state Cervantes continued five years. Some have thought that in "the captive's" tale, related in Don Quixote, we may collect the particulars of his own fortunes whilst in Africa; but even granting that some of the incidents may be the same, it is now generally supposed that we shall be deceived if we regard them as any detailed account of his captivity. A man of Cervantes' enterprise and abilities was not likely to endure tamely the hardships of slavery; and we accordingly find that he was constantly forming schemes for escape. The last of these, which was the most bold and best contrived of all, failed, because he had admitted a traitor to a share in his project.

There was at Algiers a Venetian renegade, named Hassan Aga, a friend of Arnauté Mami; he had risen high in the king's favour, and occupied an important post in the government of Algiers. We have a description of this man's ferocious character in Don Quixote, given us by the Captain de Viedma. Cervantes was often sent by his master as messenger to this man's house, situated on the sea-shore, at a short distance from Algiers. One of Hassan's slaves, a native of Navarre, and a Christian, had the management of the gardens of the villa; and with him Cervantes soon formed an acquaintance, and succeeded in persuading him to allow the making of a secret cave under the garden, which would form a place of concealment for himself and fifteen of his fellow captives, on whom he could rely. When the cavern was finished, the adventurers made their escape by night from Algiers, and took up their quarters in it. Of course an alarm was raised when they were missing; but, although a most strict search after the fugitives was made, both by their masters and by Ochali, then despot of Algiers, here they lay hid for several months, being supplied with food by the gardener and another Christian slave, named El Dorador.

One of their companions, named Viana, a gentleman of Minorca, had been left behind them, so that he might bear a more active part in the escape of the whole party. A sum of money was to be raised for his ransom, and then he was to go to Europe and return with a ship in which Cervantes and his friends, including the gardener and El Dorador, were to embark on an appointed night, and so get back to their country. Viana obtained his liberty in September 1577, and having reached Minorca in safety, he easily procured a ship and came off the coast of Barbary, according to the pre-concerted plan; but before he could land, he was seen by the Moorish sentry, who raised an alarm and obliged him to put out to sea again, lest he should by coming too close attract attention to the cavern. This was a sore disappointment to Cervantes and his companions, who witnessed it all from their retreat. Still knowing Viana's courage and constancy, they had yet hopes of his returning and again endeavouring to get them off. And this he most probably would have done had it not been for the treachery at which we hinted above. El Dorador just at this time thought fit to turn renegade; and of course he could not begin his infidel career better than by infamously betraying his former friends. In consequence of his information Hassan Aga surrounded the entrance to the cave with a sufficient force to make any attempt at resistance utterly unavailing, and the sixteen poor prisoners were dragged out and conveyed in chains to Algiers. The former attempts which he made to escape caused Cervantes to be instantly fixed on as the contriver and ringleader of this plot; and therefore, whilst the other fifteen were sent back to their masters to be punished as they thought fit, he was detained by the king himself, who hoped through him to obtain further information, and so implicate the other Christians, and perhaps also some of the renegades. Even had he possessed any such information, which most likely he did not, Cervantes was certainly the very last man to give it: notwithstanding various examinations and threats, he still persisted in asserting that he was the sole contriver of the plot, till at length, by his firmness, he fairly exhausted the patience of Ochali. Had Hassan had his way, Cervantes would have been strangled as an example to all Christians who should hereafter try to run away from their captivity, and the king himself was not unwilling to please him in this matter; but then he was not their property, and Mami, to whom he belonged, would not consent to lose a slave whom he considered to be worth at least two hundred crowns. Thus did the avarice of a renegade save the future author of Don Quixote from being strangled with the bowstring. Some of the particulars of this affair are given us by Cervantes himself; but others are collected from Father Haedo, the contemporary author of a history of Barbary. "Most wonderful thing," says the worthy priest, "that some of these gentlemen remained shut up in the cavern for five, six, even for seven months, without even so much as seeing the light of day; and all the time they were sustained only by Miguel de Cervantes, and that too at the great and continual risk of his own life; no less than four times did he incur the nearest danger of being burnt alive, impaled, or strangled, on account of the bold things which he dared in hopes of bestowing liberty upon many. Had his fortune corresponded to his spirit, skill, and industry, Algiers might at this day have been in the possession of the Christians, for his designs aspired to no less lofty a consummation. In the end, the whole affair was treacherously discovered; and the gardener, after being tortured and picketed, perished miserably. But, in truth, of the things which happened in that cave during the seven months that it was inhabited by these Christians, and altogether of the captivity and various enterprises of Miguel de Cervantes, a particular history might easily be formed. Hassan Aga was wont to say that, 'could he but be sure of that handless Spaniard, he should consider captives, barks, and the whole city of Algiers in perfect safety.'"

And Ochali seems to have been of the same opinion; for he did not consider it safe to leave so dangerous a character as Cervantes in private hands, and so we accordingly find that he himself bought him of Mami, and then kept him closely confined in a dungeon in his own palace, with the utmost cruelty. It is probable, however, that the extreme hardship of Cervantes' case did really contribute to his liberation. He found means of applying to Spain for his redemption; and in consequence his mother and sister (the former of whom had now become a widow, and the latter, Donna Andrea de Cervantes, was married to a Florentine gentleman named Ambrosio) raised the sum of two hundred and fifty crowns, to which a friend of the family, one Francisco Caramambel, contributed fifty more. This sum was paid into the hands of Father Juan Gil and Father Antonio de la Vella Trinitarios, brethren of the 'Society for the Redemption of Slaves,'[1] who immediately set to work to ransom Cervantes. His case was, however, a hard one; for the king asked a thousand crowns for his freedom; and the negotiation on this head caused a long delay, but was at last brought to an issue by the abatement of the ransom to the sum of five hundred crowns; the two hundred still wanting were made up by the good fathers, the king threatening that if the bargain were not concluded, Cervantes should be carried off to Constantinople; and he was actually on board the galley for that purpose. So by borrowing some part of the required amount, and by taking the remainder from what was originally intrusted for the ransoming of other slaves, these worthy men procured our author his liberty, and restored him to Spain in the spring of 1581.

[1] Societies of this description, though not so common as in Spain, existed also in other countries. In England, since the Reformation, money bequeathed for this purpose was placed in the hands of some of the large London companies or guilds. Since the destruction of Algiers, by Lord Exmouth[3], and still later since the abolition of that piratical kingdom by the French, such charitable bequests, having become useless for their original purpose, have in some instances been devoted to the promotion of education by a decree of Chancery. This is the case with a large sum, usually known as 'Betton's gift[4],' in the trusteeship of the Ironmongers' Company.

On his return to his native land the prospects of Cervantes were not very flattering. He was now thirty-four years of age, and had spent the best portion of his life without making any approach towards eminence or even towards acquiring the means of subsistence; his adventures, enterprises, and sufferings had, indeed, furnished him with a stock from which in after years his powerful mind drew largely in his writings; but since he did not at first devote himself to literary pursuits, at least not to those of an author, they could not afford him much consolation; and as to a military career, his wound and long captivity seemed to exclude him from all hope in that quarter. His family was poor, their scanty means having suffered from the sum raised for his ransom; and his connexions and friends were powerless to procure him any appointment at the court. He went to live at Madrid, where his mother and sister then resided, and there once more betook himself to the pursuit of his younger days. He shut himself up, and eagerly employed his time in reading every kind of books; Latin, Spanish, and Italian authors—all served to contribute to his various erudition.

Three whole years were thus spent; till at length he turned his reading to some account, by publishing, in 1584, a pastoral novel entitled Galatæa. Some authors, amongst whom is Pellicer, are inclined to think that dramatic composition was the first in which he appeared before the public; but such an opinion has, by competent judges, been now abandoned. Galatæa, which is interspersed with songs and verses, is a work of considerable merit, quite sufficient, indeed, though of course inferior to Don Quixote, to have gained for its author a high standing amongst Spanish writers; though in it we discern nothing of that peculiar style which has made Cervantes one of the most remarkable writers that ever lived,—that insight into human character, and that vein of humour with which he exposes and satirises its failings. It being so full of short metrical effusions would almost incline us to believe that it was written for the purpose of embodying the varied contents of a sort of poetical commonplace-book; some of which had, perhaps, been written when he was a youth under the tuition of his learned preceptor Juan Lopez de Hoyos; others may have been the pencillings of the weary hours of his long captivity in Africa. As a specimen of his power in the Spanish language it is quite worthy of him who in after years immortalised that tongue by the romance of Don Quixote. It had been better for Cervantes had he gone on in this sort of fictitious composition, instead of betaking himself to the drama, in which he had very formidable rivals, and for which, as was afterwards proved, his talents were less adapted.

On the 12th of December in the same year that his Galatæa was published, Cervantes married, at Esquivias, a young lady who was of one of the first families of that place, and whose charms had furnished the chief subject of his amatory poems; she was named Donna Catalina de Salazar y Palacios y Vozmediano. Her fortune was but small, and only served to keep Cervantes for some few months in idleness; when his difficulties began to harass him again, and found him as a married man less able to meet them. He then betook himself to the drama, at which he laboured for several years, though with very indifferent success. He wrote, in all, it is said thirty comedies; but of these only eight remain, judging from the merits of which, we do not seem to have sustained any great loss in the others not having reached us.

It may appear strange at first that one who possessed such a wonderful power of description and delineation of character as did Cervantes, should not have been more successful in dramatic writing; but, whatever may be the cause, certain it is that his case does not stand alone. Men who have manifested the very highest abilities as romance-writers, have, if not entirely failed, at least not been remarkably successful, as composers of the drama; and of our own time, who so great a delineator of character, or so happy in his incidents, or so stirring in his plots, as the immortal Author of Waverley? Yet the few specimens of dramatic composition which he has left us, only serve to shew that, when Waverley, Guy Mannering, Ivanhoe, and the rest of his romances are the delight of succeeding generations, Halidon Hill and the House of Aspen will, with the Numancia Vengada of the author of Don Quixote, be buried in comparative oblivion.

In 1588 Cervantes left Madrid, and settled at Seville, where, as he himself tells us, "he found something better to do than writing comedies." This "something better" was probably an appointment in some mercantile business; for we know that one of the principal branches of his family were very opulent merchants at Seville at that time, and through them he might obtain some means of subsistence less precarious than that which depended upon selling his comedies for a few "reals." Besides, two of the Cervantes-Saavedra of Seville were themselves amateur poets, and likely therefore to regard the more favourably their poor relation, Miguel of Alcala de Henares, to whom they would gladly intrust the management of some part of their mercantile affairs. The change, however, of life did not prevent Cervantes from still cultivating his old passion for literature; and we accordingly find his name as one of the prize-bearers for a series of poems which the Dominicans of Saragoza, in 1595, proposed to be written in praise of St. Hyacinthus; one of the prizes was adjudged to "Miguel Cervantes Saavedra of Seville."

In 1596 we find two short poetical pieces of Cervantes written upon the occasion of the gentlemen of Seville having taken arms, and prepared to deliver themselves and the city of Cadiz from the power of the English, who, under the famous Earl of Essex, had made a descent upon the Spanish coast, and destroyed the shipping intended for a second armada for the invasion of England. In 1598 Philip II. died; and Cervantes wrote a sonnet, which he then considered the best of his literary productions, upon a majestic tomb, of enormous height, to celebrate the funeral of that monarch. On the day that Philip was buried, a serious quarrel happened between the civil and ecclesiastical authorities of Seville; and Cervantes was mixed up in it, and was in some trouble for having dared to manifest his disapprobation by hissing at some part of their proceedings, but we are not told what.

In 1599 Cervantes went to Toledo, which is remarkable as being the place where he pretended to discover the original manuscript of Don Quixote, by the Arabian Cid Hamet Benengeli. It was about this time, too, that he resided in La Mancha, where he projected and executed part, at least, of his immortal romance of Don Quixote, and where he also laid the scene of that "ingenious gentleman's" adventures. It seems likely that, whatever may have been Cervantes' employment at Seville, it involved frequent travelling; and this may account for the very accurate knowledge which he displays of the different districts which he describes in his tale; for it is certain that the earlier part of his life could have afforded him no means of acquiring such information. Some have thought also that he was occasionally employed on government business, and that it was whilst on some commission of this sort that he was ill-treated by the people of La Mancha, and thrown into prison by them at Argasamilla. Whatever may have been the cause of his imprisonment, he himself tells us in the prologue to Don Quixote, that the first part of that work was composed in a jail.

But for fifteen years of Cervantes' life, from 1588 to 1603, we know but very little of his pursuits; the notices we have of him during that time are very few and unsatisfactory; and this is the more to be regretted because it certainly was then that his great work was conceived, and in part executed. Soon after the accession of Philip the Third, he removed from Seville to Valladolid, probably for the sake of being near the court of that monarch, who, though remarkable for his indolence, yet professed himself the patron of letters. It was whilst living here that the first part of Don Quixote was published, but not at Valladolid; it appeared at Madrid, either at the end of 1604, or, at the latest, in 1605.

The records of the magistracy of Valladolid afford us some curious particulars of our author's mode of life about the time of the publication of Don Quixote. He was brought before the court of justice, on suspicion of having been concerned in a nightly brawl and murder, though he really had no share in it. A Spanish gentleman, named Don Gaspar Garibay, was stabbed about midnight near the house of Cervantes. When the alarm was raised, he was amongst the first to run out and proffer every assistance in his power to the wounded man. The neighbourhood was not very respectable, and this gave rise to our author's subsequent trouble in the matter; for it was suspected that the ladies of his household were, from the place where they lived, persons of bad reputation, and that he himself had, in some shameful affray, dealt the murderous blow with his own hand. He and all his family were, in consequence, directly arrested, and only got at liberty after undergoing a very minute and rigid examination. The records of the court tell us that Cervantes asserted that he was residing at Valladolid for purposes of business; that, by reason of his literary pursuits and reputation, he was frequently honoured by visits from gentlemen of the royal household and learned men of the university; and, moreover, that he was living in great poverty; for we are told that he, his wife, and his two sisters, one of whom was a nun, and his niece, were living in a scanty and mean lodging on the fourth floor of a poor-looking house, and amongst them all had only one maid-servant. He stated his age to be upwards of fifty, though we know that, if born in 1547, he must in fact have nearly, or quite completed his fifty-seventh year at this time. In such obscurity, then, was the immortal author of Don Quixote living at the time of its publication.

The First Part of this famous romance was dedicated to Don Alonzo Lopez de Zuniga, Duke of Bexar or Bejar, who at this time affected the character of a Mecænas[9]; whose conduct, however, towards Cervantes was not marked by a generosity suited to his rank, nor according to his profession, nor at all corresponding to the merits and wants of the author. But the book needed no patron; it must make its own way, and it did so. It was read immediately in court and city, by old and young, learned and unlearned, and by all with equal delight; "it went forth with the universal applause of all nations." Four editions (and in the seventeenth century, when so few persons comparatively could read, that was equivalent to more than double the number at the present time)—four editions were published and sold in one year.

The profits from the sale of Don Quixote must have been very considerable; and they, together with the remains of his paternal estates, and the pensions from the count and the cardinal, enabled Cervantes to live in ease and comfort. Ten years elapsed before he sent any new work to the press; which time was passed in study, and in attending to his pecuniary affairs. Though Madrid was now his fixed abode, we often find him at Esquivias, where he probably went to enjoy the quiet and repose of the village, and to look after the property which he there possessed as his wife's dowry.

In 1613 he published his twelve Novelas Exemplares, or 'Exemplary Novels,' with a dedication to his patron the Count de Lemos. He called them "exemplary," because, as he tells us, his other novels had been censured as more satirical than exemplary; which fault he determined to amend in these; and therefore each of them contains interwoven in it some error to be avoided, or some virtue to be practised. He asserts that they were entirely his own invention, not borrowed or copied from any other works of the same sort, nor translated from any other language, as was the case with most of the novels which his countrymen had published hitherto. But, notwithstanding this, we cannot fail to remark a strong resemblance in them to the tales of Boccaccio; still they are most excellent in their way, and have always been favourites with the Spanish youth for their interest and pure morality, and their ease and manliness of style. The titles of these novels are, The Little Gipsey, The Generous Lover, Rinconete and Cortadillo, The Spanish-English Lady, The Glass Doctor, The Force of Blood, The Jealous Estremaduran, The Illustrious Servant-Maid, The Two Damsels, The Lady Cornelia Bentivoglio, The Deceitful Marriage, and The Dialogue of the Dogs. They have all been translated into English, and are probably not unknown to some of our readers.

The next year Cervantes published another small work, entitled the Viage de Parnasso