7,00 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Garnet Publishing

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Nadia rebels against the traditional role cast for women in the Arab world and joins the Palestinian resistance movement. However, she soon becomes disillusioned by their tactics and emigrates to France. The author shows the conflict between the individual and the military establishment.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

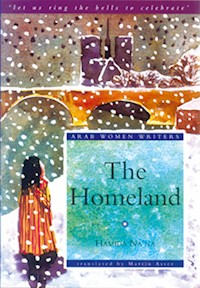

The Homeland

by Hamida Na'na

translated by Martin Asser

Published by Garnet Publishing Ltd, 8 Southern Court, South Street, Reading, RG1 4QS. UK.

www.garnetpublishing.co.uk

The right of Hamida Na’na and Martin Asser to be identified respectively as the author and translator of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

1

Introduction

1

2

3

4

Introduction

As an immigrant, you are usually confined to a specific space in that metaphoric country called exile. You walk around, a shadow in the background, your dreams of different homelands, your memories of torture, war and all the injustices you have suffered go almost completely undetected by the majority. I have chosen The Homeland for inclusion in the Arab Women Writers series, precisely because it brings the hidden history of the immigrant woman to the foreground.

Nadia, the main character in this novel, is an Arab woman living in Paris in the 1970s. She appears ordinary and nondescript yet under her Moroccan jalaba lies a complete history of the Palestinian resistance movement and the role of women in it. An ex-guerrilla fighter who was dismissed by the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), she is completely detached from her previous existence and passes unnoticed in Paris. To counter this she begins to set down her story, to write herself into existence.

Nadia’s story and her reaction to the West also shows the resentment of the immigrants who understand themselves to be more than the host society’s perception of them. “Living in Paris put the past in competition with the present … until the present and the past were locked up in a severe conflict. I refuse to take sides with either the East or the West. This continual conflict helps me discover and define myself.”1

Further tension arises because Nadia is torn between her image of herself and what the traditional, tribal and conservative society perceives her to be. Her past attempts at conformity have led to her complete alienation from her true self. In an attempt to fit with her surroundings and do what she thinks is expected, she marries a famous plastic surgeon. Nadia discovers that they have different agendas and the marriage ultimately fails. That tension between the role of women as defined by society, whether eastern or western, and the role to which Nadia aspires have a severe affect on her mental health.

During this low point in her life, she meets Frank and tries to be his ideal lover, but again discovers that he is not what she wants him to be. Consequently, Nadia loses her cultural and psychological stability: an ‘insect’ begins to gnaw at the map of her country and her inner map. In exile, she loses her identity without gaining a new sense of wholeness, so the self begins to disintegrate since it can no longer handle or control the ‘reality’ around it.

While highlighting the marginalization of Nadia within a patriarchy, a position heightened by her exile, Hamida Na’na also sets out to show the ugly misogyny prevalent in Arab societies in particular. Nadia is continually discriminated against. She realizes that she speaks a different language from her male colleagues: she is interested in theoretical discussion while her ‘comrades’ are preoccupied with their past Arab glories. Even as a revolutionary, Nadia is disappointed with her organization. She believes that action should be centred on Palestine, that hijacking planes detracts from their main aims. Manipulated into becoming a pawn of the group’s public relations vehicle, she objects and is subtly dismissed from the organization, a move which leads her to question everything she believes in.

The Homeland turns a critical face in several directions, scrutinizing the Arab world and its political organizations and the West and its repentant bourgeois revolutionaries. This latter criticism is pointed firmly at Frank. As a writer and former revolutionary, Frank has written of violent struggle in the jungles of the Congo and of armed men descending from mountains to occupy cities. Nadia is attracted to this mythical figure but Frank has changed; imprisonment in the third world has sent him running home like a prodigal son. He chooses to live in France where human rights are not violated and democracy reigns supreme. He becomes tame, joining the socialist party and starting work on a novel. Nadia realizes that the revolutionary that she had fallen in love with no longer exists and has been replaced by an establishment bourgeoisie. There is nothing to keep her in Paris and she ultimately decides to return home.

Na’na succeeds in creating two narrative lines. She shows the tensions between an individual and a political organization within the Arab countries on the one hand, contrasting this with the Arab immigrant in confrontation with an old western civilization on the other.

Much of Na’na’s narrative line set in the Arab world is based on the life of Leila Khaled2, the guerrilla fighter with the PFLP who was involved in the hijacking of TWA flight 840 from Rome to Damascus in 1969 and the attempted hijacking of an El-Al flight from Amsterdam in 1970. Khaled and Nadia have parallel experiences – like Khaled and indeed Hamida Na’na herself, Nadia is among the first women to join the Palestinian revolution and take part in military operations. Like Khaled, Nadia is a hijacker and both Khaled and Nadia undergo plastic surgery to disguise their identities. Leila Khaled and Nadia share a similar voice, they both believe in the rhetoric of Marxist-Leninist ideology, so much so that their opinions can seem simplistic or over-stated and Nadia seems to be a flat and plastic character. However she is fully rounded by the time we meet her again in Paris, where as an immigrant she suffers loneliness and invisibility and from this learns to identify herself.

The wavering of the boundaries between fiction and reality can also be seen through Nadia’s influences. She has fed herself on the popular Marxist literature of Che Guevara and Fidel Castro but has been especially influenced by the writings of the French Marxist Regis Debray, a friend of the author, who was imprisoned in Bolivia from 1967–70. Debray’s book Revolution in the Revolution became a bible for young Marxist guerrilla fighters in the Arab world. The intermingling of the characters of Frank and Debray is obvious. Nadia falls in love with Frank in Paris, thus his writings and the actual relationship make the figure of Debray omnipresent in the novel.

A further tension in this epistolary novel exists because Frank is completely unaware of Nadia’s past life in the Middle East. She decides to write him a long letter telling him about the part of her life which is hidden from him, the isolation she feels because of this denial is emphasized by the separation between the present narrative line in Paris and the past narrative line of the Arab world. The parallel lines of the woman guerrilla fighter and the life of the immigrant come together at the end when Frank reads her long letter. The two lines are no longer in confrontation with each other.

The novel is written mainly in a lyrical interior monologue and in the first person. The outside reality is seen through the eyes of Nadia and the time scale is determined by her chaotic memory. The setting moves between two decades, and the cities of Paris, Aram (Damascus), Ayntab (Beirut) and Haran (Amman) to create a history absent from official accounts. The flashbacks, interior monologue, letters and dialogues seem to be disjointed, but the engagement with the question of revolution both in the Arab world and elsewhere provide the novel with structural cohesion.

Women in this series create a different language where the patriarch is lampooned and ridiculed, and where their oral and daily experiences are placed at the epicentre of the current discourse. Since the formal language excludes them, they have pushed written Arabic closer to the spoken colloquial language in order to be able to present their experiences as completely as possible. They gnaw at the foundations of the societies which marginalize them and reject traditional notions of exclusively masculine or feminine languages. From a third space within the language they represent a culture which is based on exclusion, division and misrepresentation of their religious, sexual and political experiences.

Arab women are treated as a minority in most Arab countries. They feel invisible, misrepresented and reduced. It is therefore vital that they be heard. In the absence of many good translators from Arabic to English, a problem partly responsible for the lack of Arab cultural intervention in the international arena, Martin Asser’s translation is significant.

Now I invite the reader to open the book of Arab women’s ‘metaculture’. This book is part of a secular project, challenging the foundations of a patriarchal, tribal system. If you lift this double-layered veil, you will see the variant, colourful and resilient writings of Arab women, the fresh inner garden. You will also hear the clear voices of Arab women singing their survival.

Fadia Faqir Durham, 19951 This quotation is taken from In the House of Silence: Conditions of Arab Women’s Narratives, Fadia Faqir, ed., a collection of testimonies by Arab women novelists to be published by Garnet Publishing to complement this series.

2 For more information on Leila Khaled please read My People Shall Live: The Autobiography of a Revolutionary, ed., George Hajjar, Hodder and Stoughton, London, 1973.

1

Death-time. Time for conflagrations and far off lands. Time for vagrancy on the streets of exile. Time to be spent in strange cities, their faces clothed in the mist. All links to your distant homeland are broken. Only alienation remains. You gaze in the mirror and watch the woman in front of you dying slowly day by day, and the child within her blood being awakened.

You know it is wartime.War and time. The night always brings you back to that bitter reality. You try to obliterate yourself, hurling yourself against the pavements of loneliness. You hear the sound of your voice issuing from your throat and echoing to you emptily from the thin air. The ink has ceased to attract you. The blank sheets of paper have lost that bewitching lustre. The keen urge to confess your secret is dulled.

Where will you go?The town which you normally pass through, carrying the grand dream of return in your head, has become a prison. The wild jujube trees stick into the heart of your misfortune before vanishing under the pressure of the wind.

Night, why can’t you stop your chatter?

Why can’t you smother yourself in the gloom, and let me rest?

Since when have I felt anything for the pavement cafés, or for the faces of strangers? Or for these pavements which are soaked in the blood of my comrades? Or for the sense of failure which plunges me back into the depths of myself, vanquished? The time has come to be a woman again.

I know it is wartime.I know that it is also the time for rebirth. The time for trees seen in that hot Mediterranean country, each one clasping her daughter branches to her body, so that loneliness dies within her. But the branches must also die, since to soothe herself she crushes the life out of them.

I come from a land where everything dies at the moment of its birth, and where everything lives in its own death. I come from a land where the heavens pour water into the earth for a hundred days, and where the sun draws the waters back up into the heavens for many hundreds more.

That is where I come from, a place where war still teems at the source of every river.And I know that it is also the time of failure, and defeat, and surrender. And a time for questions which burn in my throat and echo from the abyss without being answered.

The time for nameless fears and endless waiting.

2

Paris, 1977 – I run towards you feeling the rain beating against my face and my body. I see the snow dancing in front of the bridges linking the Ile de la Cité to the old town.

Pulling my Moroccan cloak around me, I push forward into the darkness. You are standing under a riverside shelter by a street lamp. The mist eddies around you, like the music of gypsies coming up from valleys of joy. I approach:

“Sorry I’m late. My boss kept on giving me more work to do. I am always telling him that he has to let me go on time. Six o’clock means freedom as far as I’m concerned.” I laugh, then carry on: “But he’s Arab of course, so he has a bit of trouble knowing what ‘on time’ means!”

“I shouldn’t worry about it,” you reply with a smile. “Look what we did with time over here. Three world wars, God knows how many other local conflicts.”

Stretching your hand out towards me, you start stroking my rainsoaked hair. Then you shelter me under your leather jacket and we set off towards the Place Dauphine. I stop on the Quai des Orfèvres opposite the Palais de Justice and look up at you. I cannot see you properly through the storm but, amidst the wind and rain, you look like a ship’s captain, undertaking an endless voyage without so much as a single stop at port. I say to you:

“Two world wars. And we’re fighting a cause against hopeless odds … Sometimes I wish another war would start; at least we would know where we stood then.”

I see a cloud of anger pass across your face. You have many different expressions and I can never quite tell what each one of them signifies. I feel you leaning on me a little more, trying to hug me.

“Don’t be so stupid. You know it’s crazy to think like that.”Talking about war means delving into your past; talking about the Arab world means going into mine … my present too, I suppose. Whenever I look at maps of the region everything has changed. Towns getting bigger or smaller, territories being called by other names, even the passports have changed colours.

At the entrance to your building, we both look at the face of the Algerian cook in the restaurant next door. He is singing that song which makes me think back to the past and all its wounds. How I long to forget! I try to get close to you and to say to myself that we are here to erase the past.

We climb the steps leading to the wooden staircase up to your flat. I rest against you, trying to forget that face. We listen to our footsteps on the ancient wooden boards. Both of us look at the nameplate on the door of the first-floor flat. The name belongs to one of France’s leading actresses. I smile and repeat the first part of it. Then I stop and turn towards you:

“Frank, isn’t she … ”

You do not let me finish the question.

“That’s enough! She’s French, and that’s that.”

Awave of anger hits me and I become determined to finish what I was going to say. You look at me beseechingly, as though I have touched a wound which is festering in your body.

I get very stubborn in moments of resolve, however. It is as though the whole world is welling up inside me, ready to burst out whenever I want it to. This has afforded me a certain self-possession in my life, verging on narcissism, even at the moments of great danger which my life has seen. I wait until we have passed the door on which we read the name and have turned to go to the second floor. Then I lean against the wall and say:

“She’s Jewish, isn’t she?”You have a lot of trouble with the way I measure the world. A frown comes across your face and you put your hand on my shoulder, saying:

“That’s all there is as far as you’re concerned, isn’t it: Arabs and Jews. Can’t you put all that behind you?”

I remain silent, but a voice inside me says, No … Not if you are nursing a wound like mine. No.

We listen to the River Seine outside. Through the window on the stairway it mixes with the sound of the rain. There are no explosions… no blood … no screams. What a dump Paris is!

When we get to your flat, I take off my cloak by the front door and reach for the towel hanging on the wall. I wrap up my long hair and squeeze out the drops of rainwater.

“Why do you start laughing every time I ask why you came here? I know about your studies, your job, your husband, and all of that; but what exactly made you choose Paris?”

You put this question to me as you are sitting down on the sofa overlooking the river.

“I’ve told you everything. I came here with my husband, and started studying after that. When we split up I decided to stay on a bit … before going back home.”

“Do you want to go back?”

“Very much.”

“What have you got back there?”

“What did you have back in France? I’ve read your memoirs. While you were in prison you became a perfect Frenchman.”

You wince and I feel you did not want to be reminded of that time. You always try to avoid conversations about your past, as though those far-off days were no longer anything to do with you.

“In prison I used to dream of the Ile de la Cité and remember the trees in the parks of Paris. It seemed to me that I knew them all, each and every one… . ”

Two years have passed since your return to France. You came back wishing to atone and to forget. Four years you spent in prison, under the scorching sun in that far-off land … One of those ‘Third World’ countries, as they say in your language.

“Why did you go there in the first place, then?”

“What is this? A newspaper interview?”

“Frank, if only you knew how curious I am about your past. I’d read all your books by the age of eighteen. It was your books which kindled my enthusiasm and turned me into a defender of your theories of revolution.”

“You still don’t understand, do you?”

“What do you mean?”

“I mean that what I wrote back then was an adventure. And I have paid for it dearly. Please, let’s talk about something else. I don’t like talking about myself. Can’t we talk about you?”

“You know about me already.”

And I say no more. In fact you know almost nothing about me. You only know about Nadia the student, who showed up one day at the École Normale Supérieure to attend a lecture you gave about the revolutionary movement, whose black hair and gypsy features caught your eye, who had an affair with you. It was your notoriety which drew me to you, and I began an adventure the outcome of which I could never have foreseen.

Paris. January, 1976. Six o’clock in the evening.

I entered the lecture hall accompanied by a journalist friend of mine who came from one of the countries which were the scenes of your exploits. We were driven there by a desperate curiosity to see the last throes of this professional revolutionary.

“Have you heard? He’s going to be speaking at the École Normale tonight. I wonder what he’s got to say for himself?”

That is what my companion had said to me while he was talking about you. I had followed the wave of vituperation which you were subjected to in the media and among the political parties here and in the country that you had left. Like all decent people, my friend still believed in proletarian revolution in Europe and the rest of the world – well, we can always dream can’t we? All kinds of things had been said about you:

“A spoiled brat who, when he found he could not keep up the struggle, leapt back into the arms of the bourgeoisie.”

“Europe has taken back what it spat out onto the stage of World Revolution.”

“The deaths of many of our comrades can be attributed to his confessions.”

Such were the latest insults directed at you in the press. At the time I was a bit lost and depressed, trying to patch up my life again after the split with my husband. The man I married had chosen his own well-being and had left me with my inner homeland in flames. He had grown sick of my eternal see-saw from oblivion to memory and back again.

I come from the East …

I come from a land which was ablaze the last time I saw it. My comrades were facing the moment of death with no thought of ease or comfort in their heads. But I chose to flee to Europe. I gave in to the over-stuffed bellies, the sense of well-being, the inner woman. That’s what my comrades thought and that’s what I believed myself.

Why am I doing this to myself? I didn’t choose to come here at all. Iwas forced to come because I needed to get away from them for a while. I needed a rest. But there is an open wound in my side. There are jet fighters overhead in a deep blue sky. There are men’s bodies lying on the ground. I am a prisoner of the past. It takes me back to those towns which have been thrown into the fire to burn.

“Has it ever occurred to you that our relationship is not on an even footing?”

“What do you mean?”

“Well, you know everything about me and I know nothing about you. You can read all my books and you can understand everything I say, but you could be writing about anything for all I know. Do you still write poetry?”

I laugh:

“You’d better learn Arabic then, hadn’t you!”

You stretch out on the sofa and stare up at the ceiling:

“Do you think I could?”

“Have a go.”

“But I’m forty now, and I’m looking for an easy life.”

It was on cold evenings like this that we used to meet one another. Cold evenings are the best times for the coming together of a man and a woman. Their bodies feel the need for warmth and their souls have had enough of the rain.

And now?

September sun has dried up all the rain. I am alone and you are far away. But my soul is awake once more.

We spent a year of our lives together. It was a year ago that you left your house, your wife, your daughter, and moved in with me in your new lodgings over the road from the Palais de Justice. The experiment of our living together was begun.

“Frank, I can’t stand it when I think of your wife and what she might be going through.”

“What makes you think she is going through anything. We were together for fourteen years, you know. We’re just good friends now.”

I leave you in the gloom of the view of the river and move through to the sitting-room. I glance around at the piles of newspapers and magazines from various parts of the world: Nouvelle Critique, Cars of America, Afrique-Asie. Languages without dates. On the wall are maps of the world, distant continents surrounded by oceans of silence. The painting of an old Spanish sailor sitting on a God-forsaken coastline looks to me like Hemingway’s old man of the sea. I once remarked to you that it reminded me of something done by our painter friend Césire.

“Don’t be ridiculous! The only things Césire can paint are Chilean sunsets and Mexican girls with big brown eyes!”

My insistence on it being a Césire made you so irritated that you took the picture down from the wall one day, and gave me a long lecture about the Belgian artist, Delfoe, who had painted it. That day I said to you, quite simply:

“I don’t care who painted it. That face looks like one of Césire’s, especially with that strange look in his eyes. And the sun, like a brown disc in the sky without any light or warmth.”

It was the first time I had seen a sun which did not actually shine, not that it matters, I suppose.

You told me about a country where the sun rises for a long time and goes on shining as it dies. You told me:

“I used to pray for rain there. In the dungeons of torture, with my body soaked in my own blood, I prayed for my return to France. I prayed for my body to cleave to one of the columns of Paris and for it to stay there for ever. I built the dome of the Panthéon in my mind and I mapped out the streets of Paris around it. My fondest dream was that one day I would once again be able to drink a cup of coffee on the Boulevard Saint Germain.”

“It seems as though you don’t want to have anything to do with your past. I am surprised by that. If you haven’t already forgotten it, then you are trying hard to forget that once you were the very embodiment of the dreams and hopes of a whole generation.”

“They made me into a legend! I couldn’t stand that.”

I turn my head away so you can’t see the tears coming to my eyes. It is hard not to cry at moments like these, when I have to ask myself what I am doing with you.

I tell myself that the struggle has failed. Even Frank has lost faith. I go to the shower in the hope that the hot water will wash away the memories of my comrades. But within me, behind the layers of deceit, there is a secret which cannot be erased, which never ceases to torture me, which never lets me go. A retired guerrilla fighter, looking to forget in the company of another who has already forgotten.

I was on the way to being an ordinary woman again before I met you. I would eat, sleep and make love by night, and then I would go off to work in the morning. That way I thought I could live and forget …

My husband used to say:

“I don’t think you’ll ever forget. The picture of Huda al-Shafi’i follows you wherever you go. Why can’t you just live an ordinary life?”

When my husband said that, I would stare down at the ground. I can still see their faces when they left me to go to their deaths.

Frank! You mustn’t forget!

The evening hangs over the Place Dauphine. You are standing on the corner waiting for me. Darkness creeps out of the night, plunging me into the pits of alienation and oblivion. I go towards you. I put my head on your chest and smell your skin. You stroke my hair then put your arm around me. We walk together under the glow of the streetlights which are scattered about the heart of Paris. We pass along Boulevard Saint Honoré. We stand and look into the shop windows. Then we move on, as though the life of this dyspeptic city does not really concern us.

“I am leaving for Africa tomorrow. I have been asked to take part in a Revolution Day celebration there.”

I had forgotten that you were a piece of their history. I had forgotten that it was you who, once upon a time, had set light to their cities. Weren’t you just like any other man, not the great revolutionary. I gave myself up to you because you were trying to forget them, just as Iwas.

“Will you be away for a long time?”

“A month at least. Why don’t you come with me?”

“You must be joking. You know perfectly well that I can’t just leave my job here in Paris. I’ll wait for you.”

“Yes, do wait for me. Even if you are not faithful, please wait.”

I look at you with surprise:

“Frank, I shall be myself.”

At that moment we were crossing the Place du Châtelet on the way to your flat. At the point where the Boulevard des Orfèvres meets Saint Michel bridge, I saw an Arab friend of mine in the crowd. I ran after him without really seeing where he was going. You followed me with a mixture of surprise and curiosity. You didn’t think that Europe had turned me into a block of ice too, did you?

The following day saw us standing outside the departure gate at Charles de Gaulle Airport. We were looking at each other and trying to seem closer than we really felt. I heard them call your flight. I don’t know why but I had this strange feeling that this would be the last time we would see each other. I stared at the faces of the other pass-engers bustling along the walk-ways. We remembered that the time for us to part had arrived. I tried to think of something to say to you, before your departure, but the words failed me. First I muttered something incomprehensible and then I managed to say: “I’ll be waiting for you.”

Frank!

That was a month ago now Frank, and you have not called me. You have not sent me a card with a picture of the local fighters, with you in the middle.

At this moment, I feel myself drawn towards the lights of PontNeuf and the Ile de la Cité. I see a ghost in one of the shelters by the Place Dauphine where we used to meet. For a moment I think it is your ghost. The wind blows against my heart and the papers which I have clutched to my breast.

“Why haven’t you come back?”

My tormented cry is heard by a night-watchman, who turns round and looks at me with desire mingled with suspicion. I quicken my pace across the paving stones of the bridge. I hear your voice calling from far away and whispering within me. It says: “Be yourself, and nothing but yourself.” In moments of weakness, the alienation of people like me, people who are away from home, makes it impossible for them to dream.

I’ve had enough!

Do I love you?

I am not sure. All I can think about now is my wound. I think bitterly that I am living in a time of war, and that peace (your favourite subject) is nothing more than a lie which man has to believe in so that he can go on living. I suddenly remember that I cannot go home – that I have buried my past in the fabric of those old walls. It is a past which torments me and which will not leave me alone whatever I am doing.

Who am I? “You can join us if you like.” Midnight. Fifth of September 1977. Today is the Fifth of September and where is the struggle now? Has it been stifled? The commander of the military camp was not able hide his surprise when he first saw me: Frank! Snow covers the face of Geneva. Through the window of the plane it looks totally white, featureless. The plane approaches the runway. “What is it? You haven’t gone back to being a poet have you?”