4,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

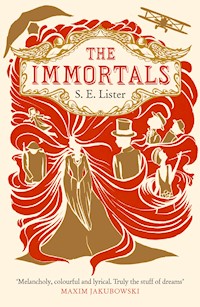

- Herausgeber: Old Street Publishing

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Rosa Hyde is the daughter of a time-traveller, stuck in the year 1945. Forced to live through it again, and again, and again. The same bulletins, the same bombs, the same raucous victory celebrations. All Rosa has ever wanted is to be free from that year - and from the family who keep her there. At last she breaks out and falls through time, slipping from one century to another, unable to choose where she goes. And she is not alone. Wandering with her is Tommy Rust, time-gypsy and daredevil, certain in the depths of his being that he will live forever. Their journeys take them from the ancient shores of forming continents to the bright lights of future cities. They find that there are others like them. They tell themselves that they need nohome; that they are anything but lost. But then comes Harding, the soldier who has fought for a thousand years, and everything changes. Could Harding hold the key to staying in one place, one time? Or will the centuries continue to slip through Rosa's fingers, as the tides take her further and further away from everything she has grown to love? The Immortals is at once a captivating adventure story and a profound, beautiful meditation on the need to belong. It is a startlingly original and satisfying work of fiction.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

THE IMMORTALS

S.E. Lister

To the Shortman son who is twin to this book with love wherever your journeys take you.

Contents

And therefore I have sailed the seas and come

To the holy city of Byzantium.

O sages standing in God’s holy fire

As in the gold mosaic of a wall,

Come from the holy fire, perne in a gyre,

And be the singing-masters of my soul.

Consume my heart away; sick with desire

And fastened to a dying animal

It knows not what it is; and gather me

Into the artifice of eternity.

Once out of nature I shall never take

My bodily form from any natural thing,

But such a form as Grecian goldsmiths make

Of hammered gold and gold enamelling

To keep a drowsy Emperor awake;

Or set upon a golden bough to sing

To lords and ladies of Byzantium

Of what is past, or passing, or to come.

W. B. Yeats, Sailing to Byzantium

Part One

1

1945

Rosa came home after seven years, in the same year she had left. It was the beginning of the wet spring she knew so well. She found their cottage on the edge of a village, the latest Hyde home in a string of many, tucked out of the way behind a disused cattle barn. There were sandbags stacked against the steps, blackout curtains in every window. Bindweed framed the doorway. Beyond the fields a church spire rose into the dusky sky, lashed by rain, its chimes silenced.

A glossy blackbird shook its wings in a tree above her head, its liquid song filling the evening air. Everything was green, fat raindrops sliding from oak leaves and splashing onto the newly sprouted daffodils on the side of the road. There was a bicycle leaning against a silver birch. The grass at her feet was thick with snails.

She knocked, and after a few moments the door clicked open. A fair-haired girl blinked up at her politely. Rosa stared at her sister, now ten years old and tall for it, and felt the whole breadth of her own absence.

Bella ducked halfway back into the hallway. She peered out from behind her hair, plainly confused as to why this ragged stranger was familiar. Rosa’s words, rehearsed across many miles and decades, caught in her throat. She had nothing to say.

“Who is it?”

Footsteps, and then Bella had been pulled aside, making way for an apron-clad woman with her hair in curlers. She had a tea-towel in one hand and a mug in the other. Her mouth grew small and tight. The mug began to shake, spilling a slick of coffee onto the floor.

“Come in. Hurry! Come in…” Her mother’s hands did not touch her, but beckoned urgently. The door was pulled closed. In the hallway Rosa looked at Harriet Hyde, who had grown thinner, her face lined and her fiery hair dulled with grey. The softness around her edges had been replaced by a strained, brittle look. She bent to dab at the stain on the floor, shooing Rosa away when she tried to help. Bella clung to her apron.

“Did you walk through the village dressed like that?” Harriet asked at last, straightening up. Rosa nodded. “Were you seen by anyone?”

“I don’t think so. It’s dark, mother.”

“Yes, yes, I know. But busybodies at their windows…” Harriet’s eyes were bulging.

“Nobody looks out of their window at this hour.” Rosa lowered the pack from her shoulders. She peeled off her raincoat, and untied the scarf from around her hair.

“You might at least have changed your clothes.”

Rosa felt her jaw clench. “That wouldn’t have been easy.”

The whitewashed hallway was lit by a single bulb, umbrellas stacked beside the door, shoes in a neat line. No pictures on the walls, no peg for visitors’ coats. She had forgotten that they always had this feel, the Hyde homes, this stale, unloved impermanence. The carpets were worn only by other peoples’ footsteps, the pencil-scratches by the door marking the heights of other peoples’ children. Occupants long-gone, each place a borrowed shell.

Harriet gestured as though it was the only movement she could remember, and Rosa tugged away her boots, wiping their muddy undersides on the mat. “You missed tea,” Harriet said, as though Rosa had merely been for an afternoon walk, lost track of the time. “We had potato dumplings. I can put together some leftovers if you’d like.”

“Thank you.”

Bella peered at Rosa from behind their mother’s apron, biting the end of her thumb. She looked pale, as though she rarely saw sunlight. When Rosa tried smiling at her, she hid herself again.

“She was only three,” Harriet said. “You can hardly expect her to remember you.” The words pierced Rosa’s numbness. Eyes filling, she turned away towards the wall, but then felt a hand against her cheek. For all her journeying, she had never seen anything so awful or so wonderful as the look her mother now wore. There was a ferocity and force in it she could not comprehend. Nothing on earth could have pulled her away from that terrifying gaze.

“Rosa,” said Harriet, with a weight of longing. Bella burrowed even deeper beneath her apron. “Rosa.”

The room splintered and blurred. A deep ache filled Rosa’s throat, and even as she tried to fight it, it broke out into a sob. Her name spoken in her mother’s voice, the rawness of that sound. Over Harriet’s shoulder, she saw somebody come to the top of the stairs. Her father towered, a faceless silhouette. Harriet pulled Bella back, and Robert Hyde came slowly, jerkily down the steps.

“I didn’t hear,” he said. “I was in the attic. With the trains.”

Fair, like Bella, Robert had aged even more noticeably than his wife. Rosa remembered him as a tall man, but his back was now bent. There were deep lines around his eyes and mouth. He looked dazed, as though he had just been shaken awake.

“Has it been…?” His hand made to cover his eyes, but Rosa quickly shook her head to reassure him.

“Seven years for me, too. You can look. I made sure of it, that I came back to the right place.”

“How old…?” he asked. His eyes, crinkled against the light of the bare bulb, darted to and fro as he attempted to work it out. He flinched when she provided the answer.

“I’m twenty-four.”

Like Harriet, he offered no embrace. In fact he did not reach out to touch her at all. He stopped several paces shy of where she stood, and simply stared. The moment stretched. After a while, he said weakly, “We didn’t expect you.”

Harriet made an odd, inhuman noise from the corner. Rosa brushed her tears away with the back of her hand. She knew that she ought to fill the silence, to attempt some kind of explanation as to where she had been, what had brought her back after so long. But it was all mired in confusion. She could barely untangle it in her own head, let alone put it into words for these barely familiar people. There was the humiliation of it, to come knocking at their door like this, after the way she had left. If she had imagined a return at all, it was the triumphant kind that would leave them chastened. Awed by all she had built without them.

“Do you have space for me?” she asked, as evenly as she could.

Robert gestured upstairs. “We’ve a spare room.”

“Daddy!” began Bella. Harriet hushed her with a stern finger.

Rosa hooked one hand around the strap of her bag. “I’ll go there now, if it’s all right. I’m terribly tired. I came a long way.”

“Daddy. Who -”

“It’s your sister, Ladybug.” Robert did not meet Rosa’s eyes. “Do you remember?”

“She doesn’t,” put in Harriet. Another sharp tug in Rosa’s throat, and Bella retreated behind the apron again.

Robert came forward. “I’ll help you with your things.”

“No need.” Rosa pulled the heavy pack back on, tucking her raincoat beneath her arm. Her parents were looking at her as though she had risen from the grave. Harriet’s hands were clasped over her reddening chest. Robert was clinging to the banister.

“Are you hungry?” asked Harriet. And then, again, “You missed tea.”

*

She found that she was trembling. Moving into the spare room, she sat down on the edge of the bed. A blackout curtain covered the window, and all was quiet. The mattress creaked beneath her, and she put her hands on her knees. The space between the walls felt suffocatingly small.

Isn’t this necessary, Rosa? Isn’t it why you found them again? To be back in a place which helps you hold your shape. Better to be pressed in on all sides, compacted and diminished. The alternative was to drift apart from herself. She had sensed it beginning to happen on the frozen beach, and the horror of it had not yet left her. The only thing worse than being back among the Hydes was to be too far from them, to have forgotten her own name altogether.

She had pictured this moment of return so many times along the journey that, now it had finally come, she had no feeling left to spare for it. Lately she could hardly bear company, and yet grew fretful when alone. To occupy her hands, she began to unpack her bag, heaping filthy clothes and worn-through shoes onto the floor. At the bottom, wrapped in newspapers from ten different decades, were her trinkets. She did not collect anywhere near as prodigiously as others she’d met, but was unable to resist the odd trophy. She lined them up on the windowsill.

A battery-operated watch with a face that had once lit up at the press of a button. A tin train painted postbox-red. From the court of a long dead lord, a small dagger in a snake-shaped sheath. And then a square gold coin and a carnival mask, from cities and years she could barely recall. A conch shell from the shore of the frozen sea. Smuggled out of the Museum’s cretaceous hall, a flat stone bearing the fossilized imprint of a feathered wing.

The door creaked, and she glimpsed a shape which ducked back into the shadow. A slippered foot slid across the carpet.

“Bella?” said Rosa softly.

Brown eyes blinked back at her. The girl moved into the doorway, wearing too-short striped pyjamas. Her hair had been plaited, and she carried a toothbrush in her hand. She squirmed shyly.

“It’s all right. You can come in.”

Bella was looking at the objects arranged on the sill. “What’s that?”

“Which one?”

Bella pointed indistinctly again, and Rosa stepped aside to give her a better view. She shuffled across the carpet and stood on tiptoe. One fingertip gingerly prodded the spiked conch, and a palm tested the weight of the stone. She didn’t know what to do with the watch until Rosa showed her, slipping it around her wrist. “It’s broken now. But that used to work the light.”

Soberly the little girl pressed the button, pressed it again. Rosa watched her face, but saw little curiosity there. Bella turned to her with the same passive expression, and Rosa wondered whether anything in her sister’s world made the remotest bit of sense.

“It’s an electric watch, Bella. From the twenty-first. The numbers would appear there, so you could see what the time was, in the dark.”

It was impossible to know whether she had understood. Bella put the watch down again, and fixed Rosa with her blank-eyed look. “I’m not allowed to tell you,” she said.

“Tell me what?”

“Where we’ve been. Or where we’re going next. It’s a secret. I shan’t tell you if you ask me.”

“I won’t ask,” said Rosa. She remembered Bella at three, round-cheeked, not quite yet steady on her feet. “But it’s all right. Ask Mother. It’s all right for me to know.”

Bella chewed at the head of her toothbrush. This idea seemed new to her. Rosa had a brief flash of how the last seven years might have played out for her sister: an unending succession of cautions and closed doors. Feet kicking through empty rooms, elbows on the windowsill, chin in her hands as the world went by outside. Rosa suppressed a shudder. And then there was something else, something unexpected and unwelcome; the creeping beginnings of guilt.

“Come on, now. I said bed.” Harriet had appeared in the doorway, wrapped in a dressing gown and with smudges of cold cream above her eyes. She beckoned sharply to Bella, who pattered away without protest. Rosa heard her thumping down the stairs, one at a time, to brush her teeth at the kitchen sink.

Harriet was carrying a tray which bore a steaming bowl and a slice of bread. She pushed the door closed with her foot, and Rosa’s stomach sank.

“I warmed this from the larder for you. Make sure you blow on it first, it’s very hot. And try not to spill on the bedclothes.”

Rosa balanced the tray on her knees. Harriet hovered while she ate – potato dumplings in a thick soup. More than the sight of her family’s faces, the familiar flavours told her she was back. Hungrier than she had realised, she crammed the bread into the sides of her mouth, pausing only when she saw the look on her mother’s face. She wiped her sleeve defensively across her mouth.

Harriet folded and then unfolded the nightdress she had been carrying under the tray. Her knuckles were white, and the skin of her chest still mottled pink. Either of these things could forecast tears. In the end she said, “You look thin.”

Rosa lowered her head over the plate, and almost returned the remark. Her mother’s gown hung too loosely. Harriet looked somehow as though she had lost weight from the inside out, as though something deeper than her bones had shrivelled. Yet Rosa’s impulse was contempt, not concern. Unconcealed weakness, more than anything, tried her patience.

“You’ll have to use some of my clothes, for now,” said Harriet, laying the nightdress down on the bed. “If you’re staying. Are you…?” Her voice cracked. “Are you staying?”

“Yes, Mother.” Rosa chewed resolutely.

“For long?”

“I can’t know that.”

“Because you can’t choose, you mean?” Harriet’s fingers worried at a loose thread on the bed-cover. “How bad has it been?” She sat down on the edge of the bed, as far from Rosa as was possible. The silence stretched until Rosa felt ill with dread, everything she’d just eaten rising to the back of her throat. Staring at the carpet, she searched for a reply which would close down questions instead of inviting more. Harriet pressed her again. “Did you have to travel far to come back here?”

“From further ahead than you can probably imagine.” The words were supposed to be dismissive, but they landed heavily, and Harriet seemed to grow yet greyer as she absorbed them. Rosa felt distant from herself, as though she was watching the scene from above. Two red-headed figures sat hunched upon the bed in the small, clean room, blackout curtains holding back the night.

“I might imagine it,” ventured Harriet. “If you…”

Rosa lifted the tray from her lap onto the bedside table. “Mother, it’s late. I’m tired. Three months, if you want to know, by air and train and on foot and every other which way.”

“From where?”

“I was about fifteen years ahead, the wrong side of Russia, and I had to come back through Kiev and Berne and Amiens. Where the right tides were, if that means anything to you. I haven’t slept in a bed in weeks. Let’s not talk now.”

Harriet’s eyes grew wider. She had not stopped staring at Rosa, as though she might read every answer from her daughter’s unkempt hair, patched clothes, weather-worn face. “I hope to goodness you didn’t cross those miles in nineteen and forty-five.”`

Rosa shook her head, and could not resist adding, “They don’t say nineteen and forty-five, Mother. Just nineteen forty-five, if you remember from when you were one of them. Eighteen sixty-one. Fifteen thirty-nine.”

“Oh, they do, do they?”

“Yes. It’s not difficult, and it makes you sound simple when you get it wrong.” Rosa pounded the pillow with her fist.

“Have you seen yourself?” said Harriet. “I shall have to cut your hair.”

“I’ll cut it.”

“Well, you’ve always done just as you wish. Just make sure you don’t draw any attention. You can’t leave the house again looking like that. We’re hoping to stay here until the end of the year.”

“And then where?”

Harriet met her gaze. “Some other town,” she said. “Some other house, and the same months all over again. What did you expect? Our war goes on.” Her eyes ranged over her daughter’s face, and Rosa realised that behind all her questioning, she was starving for reassurance. No rest for the mother of the runaway, not even now that she was returned alive. Harriet wanted to hear that the fears of her night hours had been groundless: that the world beyond nineteen forty-five had surprised with its kindness. Rosa let the silence limp on. Even if she had wanted to, she could have offered no such comfort.

She could perhaps have lied, but Rosa found that her anger against the Hydes had not yet burned out. Being angry with her father was useless; it simply slid over him. Harriet, less to blame, had always attracted more of Rosa’s anger because she understood it. If her mother had not chosen to resist, Rosa was sure, Harriet’s anger might have eclipsed her own.

You chose wrong, Mother, she thought. You should have cut your losses long ago, and left him. You might have been set back on a more ordinary path. Bella and I would never have been born, and no great tragedy for us.

Harriet stood and picked up the tray from the bedside table. “I’ll let you sleep.”

Rosa gave a brusque nod.

“I’ll leave the landing light on. There won’t be any raids, we checked before we chose this town. The latrine’s at the end of the garden.” She made for the door, but hesitated, turning back again. She was holding the tray too rigidly, the bowl and plate rattling as her hands shook. Her look was bare as winter ground.

“I do not know what you mean by coming back to us. But please understand – we grieved you, Rosa. We already grieved you.”

Rosa wrapped her arms around her chest. Harriet’s mouth was tight, her eyes damp.

“We had to, in the end. We have done our grieving.”

*

Without turning out the bedroom light or changing into the nightdress, she curled up on top of the covers. They were rough against her face, and smelled of washing powder. She drifted almost at once into an uneasy doze, waking several hours later with a sour taste in her mouth, woozy and disorientated. The clock on the wall told her that it was two in the morning. Her whole body was stiff and aching from her journey.

Downstairs in the kitchen, Rosa turned the groaning tap to splash cold water onto her face. She peeled back the blackout curtain and looked for a moment at her dim reflection on the window, freckled and frowning, features hard as her calloused hands. Her hair straggled to her waist, first grown that way for her time in the fifteenth, when she had coiled and fastened it with jewelled pins. The memory brought a wave of pride and sadness and longing. She found a pair of scissors in the drawer and, without much care, hacked off everything below her shoulders.

She stuffed the cuttings into the bin and then stood at the window, holding back the curtain again so that she could look out into the moonlit garden. Bella’s hula-hoop and skipping rope had both been abandoned on the lawn. Wind blew through the cornfields beyond the hedgerow, the silent church tower on the hill. Not a soul to be seen, and the rain still falling.

Instinctively Rosa scoured the shrubbery for the sight of a pale face. Branches blew to and fro, and there could be somebody hiding in that patch of darkness, beneath the weeping leaves of that tree. As a small girl, in a different home, she had once been terrified by the sight of a man who appeared from nowhere at the bottom of the garden. He had pointed a gun at her, flicked back the safety, and then vanished without trace. She had never spoken of this to her parents, or indeed anybody except Harris Black, who claimed still stranger sightings.

The thought of the stranger from the garden sometimes caught her off-guard, and set her shivering. Had she really seen him again that time in Reims, in the deep of the cathedral? She was not sure that her mind hadn’t conjured him. It was impossible to reason away the fear that his appearances, real or imagined, awakened in her.

A noise from above caught her attention, pulling her back to the present. She moved to the bottom of the stairs, and saw a ladder hanging down from the brightly illuminated attic hatchway. The sound of mechanical whirring floated down. She climbed to the upstairs landing and ducked back into the spare room to pick up the tin train from the windowsill, before ascending the ladder.

She entered through the hatch without knocking. Her father knelt in the centre of a miniature train track, which had been laid out around the room. As well as the trains, there were lines of tiny trees, matchstick houses, model sheep and cows. Everything had been painstakingly hand-painted. Robert looked up when she entered, his spectacles balanced near the end of his nose, caught in the midst of assembling another section of track.

“Does it work?” asked Rosa.

Robert pushed his glasses up the bridge of his nose. “One of the trains is just for show. The other’s got a steam engine, though. I had her going full speed yesterday.”

Rosa moved away from the ladder, and crouched at the edge of the room. A clock ticked dryly upon the wall. The space was lit by a single bare bulb, suspended from the beams overhead. Her childhood had been full of such places, of her father’s glue-smelling workshops, his perfect little towns and villages. At the end of every year, they were demolished, to be doggedly re-built somewhere new.

“Here. Watch.” Concentrating intensely now, he pulled a box of matches from his pocket and struck one. He held it inside the mechanism of the larger train, which after a few moments began to emit clicking noises and puffs of grey smoke. Robert held it steady as it began to strain forward, shaking out the match with his other hand. Then, with an eager squeal, the steam train headed off on a rapid loop of the floor, taking the curve so quickly that it almost overbalanced.

Despite herself, Rosa laughed, sitting back to admire the engine’s progress. But as it completed a circuit of the track and continued to another, looping around again and again with blind urgency, she was aware of her smile fading. As the train stuttered to a halt, she tasted the old bitterness.

“You’ll find us very much the same,” Robert said. He picked up the spent engine, and dusted it off. He was nervous as a schoolboy.

“I got you a present.” She leaned over the track and held out the tin train, which he took carefully. “It runs by clockwork. You wind the lever, here –”

He wore a small smile, now, as he prised the back of the train apart to admire the interlocking cogs and gears. “This isn’t quite like any other I have. A little more primitive. Beautifully crafted, though.” Rosa waited for him to ask where she had got it, but the question did not seem to have occurred to him. It had never been so plain to her that he could not think himself outside the year, outside the familiar sphere of the world he had made.

She had wanted to slap Harriet to silence her interrogation, but now she felt the urge to shake Robert until he came awake. Until he could see her. The frustration of it was so overwhelming that it made her numb rather than furious. She wanted to say, can’t you try? Can’t you reach a little for just the nearest, the most mundane of the places I have been?

Her tongue felt thick. “Don’t you want to know how I found you?” she asked.

Her father didn’t look at her. Unsteadily, he adjusted his glasses on his nose.

“I had help,” said Rosa. “There’s a place where they know all about us. People like us. You’re in their records.”

“I see, I see.” Robert was blinking very rapidly, and looking at him, she was surprised by a pang of something resembling pity. If he could not react even to that, perhaps nothing should be expected of him. It was merely that he seemed so old to her, his fair hair thinning, his shoulders hunched. He looked shrunken and small. Somewhere in her hardened heart, she lost another scrap of certainty.

“When are we at, Daddy?” she said softly.

“Let me see… March eighteenth. The Yanks almost have it at Iwo Jima. Heavy bombing on Japan, poor devils, though they’ve seen nothing yet. They’ve not had it so bad here, far enough out of London.” He rubbed his hands together vaguely, and a small smile drifted across his face again. “Still a month and a half until my red-letter day.”

“Yes, I suppose it must be.” Her dinner now sat heavy in her stomach. Nausea came over her, and she no longer wanted to be even under the same roof as her father. The tenderness which had almost blossomed in her moments before withered and died.

Preoccupied once more with the mechanism of the tin train, Robert began to hum tunelessly. Rosa watched him, and resignation folded in upon her. You’ll find us very much the same. She hugged her legs to herself, resting her chin on her knees, as the clock on the wall parcelled out the seconds. She left him, before long, for her bed.

*

She slept at last to the distant, uneasy sound of planes droning overhead. Her newly cut hair scratching at her neck, she tossed and turned, waking frequently in the unfamiliar room. Her dreams were filled with skaters who whirled and danced among snow-heaped pines, with the squeals of speared hogs, with city streets which dissolved like sand. With the great fish that had swum in the deepest waters, before the world was old.

2

Arline

Nineteen forty-five had first fallen away from her like an unbuttoned dress. She had discarded that year at her feet, stepped out of it and felt fresh air upon her skin. It had happened when she was seventeen, on the night of the awful row, when she had done what she’d so long threatened to do and gone running from her parents’ house into the night.

Harriet’s voice still screaming downstairs, Robert’s lower, helpless tones. Still sobbing, Rosa had taken little time to pack. A satchel stuffed with a few necessaries, underclothes and skirts and blouses all haphazard and inside-out. A toothbrush and a bar of soap. Her father’s precious fob-watch in her pocket, because it felt good to take it. She slammed the front door as hard as she could, and then her footsteps were clattering along the Shoreditch lanes where they had lived, that time around.

The night was thick with chimney-smoke. The streets in that place were still cratered and scarred; washing was strung between the windows; boys on bicycles teetered past her. Outside the Mission, an old woman hunched on the steps, drinking from a brown paper bag. People heading into the pictures for Blithe Spirit. Rosa wiped her eyes on the backs of her hands, but her tears would not stop.

She could barely see where she was going. Past a huddle of wardens and across the path of a swerving motor-car, past a row of allotments and within sight of St. Paul’s. A stitch forced her to slow, gasping. Along the river, Big Ben was visible through the falling darkness, its face illuminated. It was past the end of April, and the blackout was ended.

Rosa kept running, and as she ran it seemed to her that the air had changed, or that her body had become painfully sensitive to the hardness of the ground and the beat of her own heart. She tried to stop, grabbing hold of a street-lamp, but dizziness carried her to her knees.

Her whole baffling lifetime rose up in her. Her throat burned, still, with the hot words she had flung at her mother and father. I won’t forgive you. I hope that you die here. There on the pavement, with the city spread out on every side, she came loose from all that she had ever known. A wave swept her forward, stomach dropping into free-fall and limbs flying, the buildings on the darkened street dissolving like so much sand.

*

And re-forming again. She had journeyed before, of course, but never like this. It was daylight. She tasted the new century before her other senses had caught up, rolling it to the back of her tongue. Everywhere the noise of engines, car horns, musical tones, a ceaseless hum and roar which seemed to be carried on the air. She understood at once what had happened, but the shock of it kept her pinned to the ground.

She was still on the pavement, still on a street near the bank of the river beside a grassy verge. She fought the shaking in her knees to stand up, hugging the overflowing satchel tightly to herself. The place was the same, and it was all altered. It was like hearing a familiar song played on a broken record, verses skipped, the melody distorted. As to how far she had come, she could not begin to guess. Bruised, every part of her body trembling from the fall, Rosa cast about for some clue. Pulling a newspaper from a bin to glance at the date, she was overcome by dizziness again, and sank down again by the side of the road. She let out a hoarse laugh.

Not one passer-by spared her a glance. She drank the sight of them in greedily. The brightness of their clothes, the women with their exposed legs, so purposeful and swift, their faces made up so radiantly. Some of the men had long hair, too, or loose shirt collars, and none wore hats. They spoke not to one another but to devices held in the palms of their hands.

The road was so full of motorcars that they were barely moving. Signal-lights flashed, and people on bicycles wove their way between the traffic. Some of the buses were plastered with posters showing beautiful faces or exotic scenes. Television screens half as tall as buildings flashed moving advertisements for perfume and beer and who could tell what else. On the opposite bank of the river, a slowly turning white wheel dominated the skyline. After the drabness of nineteen forty-five, it was too much to take in.

Rosa waited until the century had solidified beneath her before standing up again, clinging to a rail for support. It was then that she noticed the dome of St. Paul’s, serene and unchanged amongst all the towering, gleaming new structures. She laughed aloud again. Her father kept a cut-out newspaper picture of that dome surrounded by clouds of black smoke, lit in a glorious white blaze as though heaven itself had preserved it from the bombs. During the Shoreditch year, and in the Camberwell year when she was twelve, she had crept inside several times. Played hopscotch on the chessboard floor. Lingered among stone statues of saints in the fusty quiet.

She looked down at herself, brushing off her clothes with new self-consciousness. She was wearing a brown coat over her dress, stockings and patent leather shoes, all plain enough to draw no glances. If she was sharp enough, bold enough, nobody need know where she had come from. She needed only to stay safe, to watch until she was ready to become one of them.

*

She had no clear plan. It had never been possible to make one, with no clear idea of what lay beyond nineteen forty-five. Now, caught up in the bustle of this miraculous new London, she knew that she wanted to go wherever these people were going: to wear what they were wearing, to be swept along in the flow of the age.

But first she must pursue more immediate needs. She found a pawn shop, and without looking to the left or right approached the counter and took the fob watch from her pocket. It was examined by a slow-moving man who grunted and shuffled across to the till. Rosa stood on tip-toe to look at the display in the cabinet - diamond earrings, a rack of gold rings, an array of items which were completely mysterious to her. Were those cameras? They were small enough to be slipped into a pocket. She misted the glass with trying to stare more closely. When paper was handed over and clutched in her clammy hand, she exited quickly. She paused on the threshold to look over her spoils. Two red notes, printed with the head of a curly-haired queen.

Making a quick list in her mind, she squeezed in and out of shops until she had bought sturdy waterproof shoes, a thick coat and small supply of food. When darkness fell, she found a doorway. She stayed awake, chewing hungrily at a chocolate bar, the hood of her new coat pulled up. Turning her head to follow the progress of every passer-by, her eyelids began to droop. It was not until the pavements had emptied that it occurred to her to be afraid.

Rosa had lived in many places, but she had never slept a night anywhere that was not a Hyde home. She huddled as far back into the shadows as she could, turning her head at every sign of movement beneath the street-lamps. Don’t be a baby, she told herself. A trio of drunken figures lurched too near after a distant clock had struck three, leering, too loud. One of them urinated in the corner of her doorway.

The next morning, stiff with cold and tiredness, she bought a small knife and kept it tucked into her belt.

She used it, in the nights which followed, to threaten a man who trailed her in her search for a sleeping place, a too-curious dog, and a stringy woman who approached her with an aggressive tirade she couldn’t understand. She witnessed many thefts – some furtive, purses snatched from handbags, others ending with fists raised and blood on the pavement – and held her precious satchel all the closer. Not much longer, she promised herself, and when her money ran out, put out a cardboard carton to collect coins. She washed in public bathrooms and drank from the fountain in the park. Soon, I will find my feet.

Sitting in the corner of a cafe, she listened, rapt, to the conversations on every side. A group of girls talked about their boyfriends, whispers punctuated by gales of laughter. Two businessmen blew on cups of black coffee; a young boy bent his head over a flickering screen. A lone woman in green sat wholly absorbed in her book, marking pages with the pen in her hand. Rosa did not have a very clear idea how such people occupied themselves, and as she watched them, she attempted to imagine how their days might be arranged. They must have houses which they left in the morning and returned to at night, homes which remained theirs, year after year. They might have families who were waiting for them there. They might have studies or work or pastimes which filled their hours and their minds.

She settled arbitrarily on the thought of her mother’s profession. Harriet had been a teacher before her fateful encounter with Robert, dress tucked between her knees as she bicycled to school along the lanes, arriving in the classroom to put frogs in jars and scratch Latin grammar onto the blackboard. I could do that, thought Rosa, once I’m accustomed to this place. Her heart lightened.

She balanced along the narrow safety of this idea as though walking a tightrope. There will be more, things will be better. It was autumn, and as she strode through the streets to St Paul’s, brown leaves whirled about her feet. Head down, shoulders hunched, hands tucked in the coat’s deep pockets. Approaching the pillars around the cathedral door, she saw a crowd of people with cameras and leaflets. They formed an orderly queue inside the entrance hall, and Rosa saw them handing over money to a man in a booth.

She sat on the steps and watched the bustling streets below, chin resting on her hand. The noises and the smells of the city crowded her senses, this place that had changed almost beyond all knowing. She welcomed every alteration as a bracing gasp of air.

Sixty years, she thought, barely more than sixty years forward. I would have lived this long, in a lifetime like one of theirs. I might have still been here, a silver-haired old woman shuffling down the street with my shopping. Mumbling memories of our last year at war, of our red-letter day.

*

She discovered that she was merely one of many in London without possessions to her name or papers to prove her existence. There were rooms behind boarded-up windows where they slept packed in like tinned sardines. At first she looked hopefully into each face, wondering which years and decades they might have come here from. But it did not take long to realise that they had made journeys of a different sort.

The city’s secret citizens spoke in foreign tongues, or not at all. They were grey-faced men who had crossed borders clinging beneath trucks, women whose hands were red and thickened from hard labour. Girls Rosa’s age hid their hair beneath scarves and slept with one eye open, and she began to do likewise. Sometimes one or a pair would vanish overnight, and it was not long before Rosa found herself in a state of constant watchfulness. When approached, even with the friendliest gestures, she shook her head violently and brandished the knife. She stopped sleeping outside, and in whatever shelter she took, she kept her back to the wall. You’d never have credited me with this, Mother, Father – with such a keen instinct for survival. Her pride in this newfound freedom burned more fiercely than her fear.

She took a job where no papers were signed and no questions were asked, vacuuming carpets along the long corridors of an apartment block. She did not ask how to work the device, but discovered for herself how to plug it in and flip the switch. The noise made her teeth rattle. When she was let into the flats to scrub ovens and spray bathroom tiles, she drank in every detail. Coloured televisions with screens a yard long, lamps which dimmed and brightened at the lightest touch, showers which jetted powerful streams of hot water. Her heart turned enviously in her chest and she began to store up thoughts of having such a home herself. She stood in the corners of their rooms, dustpan in her hand, and trembled with hope and desire.

The inhabitants of these places came and went – women in smart suits, men with leather briefcases. If any of them addressed her she pressed her lips together and shook her head. Better to pretend she had no English than to use the wrong words, not to know words which were commonplace here. Alone, she opened cupboards and desk drawers, furtively shook food out of packets. Once she fell asleep curled on a mattress so soft that it moulded to fit her body’s shape.

Her favourite was on the fifth floor. Its rooms were large and its walls hung with photographs. These showed a man and a woman, both fair-haired and smiling, holding a young girl and a baby. The curtains were patterned with red and cream flowers, and light poured in all through the shortening hours of the day. Rosa would complete her work as quickly as she could, then sit at the kitchen table in a shifting patch of sun, eyes closed.

She made sure to leave before they came home, but several times she passed them in the corridors on her way out. The baby was now a pudgy toddler in a woollen hat, the girl – clinging to her mother’s hand – about Bella’s age. Rosa turned to look over her shoulder as the family vanished into the lift, and felt an unexpected tug in her stomach. She had not thought to wake her sister, the night she fled the Shoreditch house. Perhaps Bella had come to her room later in the night, when the planes were droning overhead, and found the bed empty when she crept under the covers in the darkness.

The children here shared a bedroom with a shelf of picture books and a cupboard full of toys. Once she had vacuumed, Rosa sat on the edge of the girl’s bed, twisting the electric cord around her finger. She leaned into the little one’s cot and pulled the tab which brought the musical mobile to life. It played a tinkling lullaby while rotating gently in circles.

She stripped the parents’ bed to launder their sheets, which she sometimes smelled furtively, inhaling sweat and perfume combined in a musk which seemed mysterious, and deeply private. Like the home itself, the scent unlocked a longing in her which she had never known existed. Her heart pounded faster with it. Before the bathroom mirror, she smeared scarlet lipstick on her mouth, smoky powder on her eyelids. Throwing open the curtains in the darkening afternoon, she saw London laid out before her, lights glinting in the window of each office-block and all along the winding river.

In a moment of sudden joy, she tugged the scarf from her hair and flicked the switch on the radio. Eyes closed, heedless of any outside gaze or the chance that a key might click in the lock, she jumped and wriggled to the unfamiliar music. She stretched her arms and held up her palms as though to embrace this strange age; as though to bask in the wide-open space of a year which would flow outward and onward.

*

Winter sank down over the city, muting everything. Rosa slept behind the machines in the laundry room at the tower block, where heat from the boiler next door kept the frost from her eyelashes. The machines rattled and juddered until long past midnight. To prevent doubt from blowing in under the door along with the chill wind, she replayed the scene of the row over and over in her head, and kept her anger alight. Anywhere but there, anywhere but nineteen forty-five. Here, at least, she could breathe.

There will be more, things will be better. Details of this bright future eluded her, but it didn’t matter. When her rummaging through bins yielded only scraped-out tins or overripe fruit, she took food instead from the shelves and cupboards of the rooms she cleaned. A little here, a little there. With Christmas around the corner, she licked her fingers and dipped them into jars of mincemeat, pocketed fresh-baked biscuits cooling on wire racks. She cleared away the crumbs carefully afterwards.

When she had finished work for the day she wandered the lamplit streets, breath misting the dark air, moon on the rise. Bright bulbs and plastic snowflakes hung in strings between the shops. Behind the curtains of every home, glowing yellow light. Rosa watched the shadow shapes behind these windows as they moved and merged. She saw a sign, Room for Rent, and counted the money in the brown envelope she kept in her coat.

Everything seemed so simple for the strangers who resided warmly behind those walls. There was nothing they could possibly want. Late one afternoon she sat back, suddenly dizzy, from scrubbing bathroom tiles in her favourite apartment. As she wiped her sleeve across her forehead, she thought that she smelled pine needles. A waft of something smoky. Standing and pulling off her gloves, she moved into the kitchen, then the darkened bedroom to search out the source of the smell. It was gone, but her head was still spinning.

Rosa sat down slowly on the bed. Her fingers smoothed the covers on each side, lingering on the soft cloth. She picked up a watch left on the father’s bedside table and gave it a careless shake, wondering whether the light inside would be extinguished. It wasn’t, and she busied herself for a few minutes fiddling with the dials. No doubt Robert would have understood the mechanism. She pocketed the watch without any intrusion of conscience and proceeded to rummage in the mother’s drawer, which contained an engraved bracelet in a wooden box. It was silver, and supposing it might be worth something, she pulled it out of its case.

Rosa placed her cleaning things on the kitchen table, and stood still for a moment in the empty room. Faces looked down at her from the photographs on the wall. Then she let out a laugh and left without bothering to lock the door, descending the steps two at a time. Out in the blustery afternoon her feet carried her with new, buoyant purpose. Where would you like to live, Rosa? Somewhere small at first, of course, but perhaps later… perhaps in days to come…

She had barely made it three streets away, towards the twilit Thames, before the city began to crumble at the corners of her vision. With a lonely, echoing rumble, towers receded to nothing and roads retreated like measuring tape.

Her body bent backwards. The smell of pine-needles, of fish-flesh and woodsmoke. It was still dark. She had journeyed again.

*

How far, this time? Forward again, or back? Thin though her schooling had been, she could hazard a fair guess. There were wrought lamps with gas flames, cobbled streets that teemed with carriages, passers-by in long coats and caps. Like a book illustration, like a postcard. She gasped for breath on a pavement that was thick with straw and stinking dirt, and pulled herself quickly upright.

Greyish fog swirled and thickened on every side, and the people of this age swam through it like fish through the element they had been born into. London lay deep in flickering shadow, dark almost as a blackout night, while white ash floated up from the firepits in side-alleys and a man turned a marble-eyed pig on a glowing spit. Blinkered horses flared their lips about the bit, and snatches of music drifted from tavern windows. This city, with the towers of glass and steel felled from its skyline, seemed more familiar.

She bent to tie her bootlaces. Feeling the brown envelope in her pocket, she was furious with herself. What use were those silvery slips of paper with their curly-haired queen, here where the woman on the throne was straight-locked, po-faced? All her work, the scrubbing and the vacuuming, had been useless. Now she would have to begin again. She felt tired and disorientated, and could not bring herself to remove the anachronistic coat, or the scarf from her hair.

Bags of hot chestnuts hung from carts, and holly wreaths were nailed to each door. With a feeling of brittle unreality, she followed the drill which had served her last time. “Might you point me to a pawn shop?” she asked one of the chestnut-vendors. “Or a jeweller’s?”

He looked her up and down. “In carnival costume, miss?”

“I’m a performer in a festive play.”

“Stores near here’ll be closing now, save on Straight Street, where some keep later hours. You might try there. What is it you’re dressed as, may I ask?” When she fumbled for an answer, he pressed her. “What manner of play is it?”

She raised her chin as she looked back at him. “A comical one.”

The silver bracelet fetched enough for a long dress, which she purchased from the first open store she passed, and pulled on hastily in an alleyway. It fit badly, trailing on the ground. Together with the coat and the satchel, she knew it only made her look more peculiar. There seemed more cause to be frightened here than in the London of the twenty-first. The night was thicker, its sounds more chaotic.

And there was something else, too, inside her. A deeper sense of panic and bewilderment. Did I plan for this? Did I know that this would happen? That I would journey again? She could not remember. In her head she tried to re-assemble the life that had started to take shape in the twenty-first, to imagine how it might look here. The substance of the imagined thing seemed frighteningly thin.

The night was bitter. Desperate for warmth Rosa peered into the windows of several nearby taverns, and stood for a while warming her hands by a baked potato vendor’s fire, until the proprietor shooed her away. Eventually she ducked inside a theatre, slipping easily past the ticket-men and into the uppermost circle, where she slept curled on a seat in the back row. She woke in confusion during the second act of an opera whose name she’d paid no heed to. The hairs on the back of her neck were standing on end. A shiver worked its way down her back, and she sat up as a high and otherworldly melody rose to the theatre’s rafters.

I dreamt I dwelt in marble halls

With vassals and serfs at my side.

And of all who assembled within those walls

That I was the hope and the pride.

I had riches too great to count, could boast

Of a high ancestral name.

But I also dreamt, which pleased me most

That you lov’d me still the same,

That you lov’d me, You lov’d me still the same,

That you lov’d me, You lov’d me still the same.