Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Parthian Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

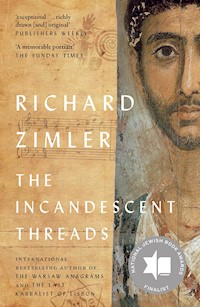

ONE OF THE SUNDAY TIMES' BEST HISTORICAL FICTION BOOKS OF 2022 'Zimler is an honest, powerful writer' – The Guardian 'A memorable portrait of the search for meaning in the shadow of the Shoah.' – The Sunday Times From the acclaimed author of The Last Kabbalist of Lisbon and The Warsaw Anagrams comes an unforgettable, deeply moving ode to solidarity, heroism and the kind of love capable of overcoming humanity's greatest horror. Maybe none of us is ever aware of our true significance. Benjamin Zarco and his cousin Shelly are the only two members of their family to survive the Holocaust. In the decades since, each man has learned, in his own unique way, to carry the burden of having outlived all the others, while ever wondering why he was spared. Saved by a kindly piano teacher who hid him as a child, Benni suppresses the past entirely and becomes obsessed with studying kabbalah in search of the 'Incandescent Threads' – nearly invisible fibres that he believes link everything in the universe across space and time. But his mystical beliefs are tested when the birth of his son brings the ghosts of the past to his doorstep. Meanwhile, Shelly – devastatingly handsome, charming and exuberantly bisexual – comes to believe that pleasures of the flesh are his only escape, and takes every opportunity to indulge his desires. That is, until he begins a relationship with a profoundly traumatised Canadian soldier and artist who helped to liberate Bergen-Belsen – and might just be connected to one of the cousins' departed kin. Across six non-linear mosaic pieces, we move from a Poland decimated by World War II to modern-day New York and Boston, hearing friends and relatives of Benni and Shelly tell of the deep influence of the beloved cousins on their lives. For within these intimate testimonies may lie the key to why they were saved and the unique bond that unites them. 'Rarely is a novel published that evidences such extraordinary literary talent… AN ABSOLUTE MASTERPIECE' – Açoriano Oriental

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 762

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

i

PRAISE FOR RICHARD ZIMLER

Hunting Midnight

‘From Midnight’s first words … the reader is charmed. Zimler’s ability to lay bare the horror of injustice, to find universal truths and poetry in everyday existence, and his faith in the human spirit, make reading Hunting Midnight an uplifting experience.’

Jerusalem Post

‘Zimler’s book is a triumph of modern fiction: an absolutely gripping narrative of love and loss set against a backdrop of fantastic historic drama. Zimler rises to the incredible quality of his bestselling The Last Kabbalist of Lisbon. The characters are rich and fully realized, and their conflicts are vital and real. They grow throughout the book, so that by the end you feel a real intimacy with them. I loved this book. Read it at once.’

Andrew Solomon, winner of the National Book Award (USA)

‘An ambitious historical epic from a superbly talented historical novelist, capable of combining fascinating broad-canvas glimpses of history with the most intimate portraits of the human heart in turmoil.’

Booklist (USA)

‘A page-turning story of cruelty, conspiracy and escape, plot-driven in a way that makes you read more greedily, eager to get to the iiend … Brave and intriguing … A delicate exploration of the ways in which repressed religion and culture shape experience, identity and loss.’

Sarah Dunant, author of The Birth of Venus

‘I defy anyone to put this book down. It’s a wonderful novel: a big, bold-hearted love story that will sweep you up and take you, uncomplaining, on a journey full of heartbreak and light.’

Nicholas Shakespeare, author of Bruce Chatwin and The Dancer Upstairs

‘Zimler is always an exhilaratingly free writer, free of ordinary taboos, and Hunting Midnight shows him at the height of his powers.’

London Magazine

‘An epic drama, spanning three continents and more than twenty-five years, building up to a genuinely moving climax.’

Literary Review

‘Reading Hunting Midnight was like discovering a rare gem. Richard Zimler is a brilliant author with a touch of genius.’

Rendevous Magazine (USA)

‘Enthralling … Hunting Midnight is a shamelessly sprawling historical novel, spanning continents, Napoleonic wars, a secret Jewish family, Kalahari magic and slavery.’

Sydney Morning Herald

‘Zimler’s tale of friendship and revenge [becomes]a search for the unexpected … Zimler is an honest, powerful writer.’

The Guardian

‘Zimler’s writing is pacey and accessible without ever patronising the reader – deeply moving’

The Observeriii

Guardian of the Dawn

‘The strength of Guardian of the Dawn lies in its rich historical setting and in Richard Zimler’s creation of an idiomatic language that reflects the religious and cultural diversity of place and period … remarkable.’

Times Literary Supplement

‘A terrific storyteller and a wizard at conveying a long since vanished way of life.’

Francis King, Literary Review

‘While this novel is a testimonial for the thousands who suffered under the Inquisition in India, it is also a riveting murder mystery [by a] master craftsman.’

India Today

‘This is the third volume in Zimler’s luminously written series about the Zarcos, Sephardic Jews from the Iberian Peninsula. While the beginning reads like a nostalgic coming-of-age story—though in an exotic locale—a more suspenseful tone steps in halfway through. Its last sections deliver a warning on the dangerous sweetness of revenge, and how it can lead to a tragedy of Shakespearean proportions. As haunting and mysterious as India itself can be, this novel delves into the darkest currents of the human mind and heart. Few readers will emerge untouched.’

Historical Novel Society

‘Crime and punishment work their usual spell in this deeply absorbing work.’

Kirkus Reviews

‘Parallels with Shakespeare’s Othello are not accidental but nothing, to the smallest detail, is accidental with a writer who has fairly been called an American Umberto Eco.’

The Advertiseriv

‘An exciting adventure story … Scrupulously researched … Fascinating.’

The Independent

The Seventh Gate

‘A gripping, heartbreaking and beautiful thriller … unforgettable, poetic and original.’

Simon Sebag Montefiore

‘The Seventh Gate is not only a superb thriller but an intelligent and moving novel about the heartbreaking human condition.’

Alberto Manguel, author of The Library at Night

‘Mixing profound reflections on Jewish mysticism with scenes of elemental yet always tender sensuality, Zimler captures the Nazi era in the most human of terms, devoid of sentimentality but throbbing with life lived passionately in the midst of horror.’

Booklist (starred review)

‘Adding a touch of Jewish mysticism to his historical thriller, Zimler … excellently captures the gamut of tumultuous emotions in his intense and detailed portrait of a city destined for war, and his exceptionally drawn characters struggling to survive in a world gone mad make for an unforgettable story.’

Library Journal (starred review)

‘Zimler, a seasoned American writer living in Portugal, combines sexy coming-of-age adventures with coming-of-Hitler terrors in this powerfully understated saga.’

Kirkus Reviews

‘The Seventh Gate is unforgettable … The reader will be haunted by these brave characters and the stirring murder mystery … ThevSeventh Gate builds frustration and anxiety into a devastating and haunting conclusion … gripping, consuming, and shocking … unforgettable.’

New York Journal of Books

‘Zimler … surpasses himself with this coming-of-age epic set in Berlin at the start of the Nazi era … the whodunit is captivating enough, but the book’s power lies in its stark and unflinching portrayal of the impact of Hitler’s eugenic policies on the infirm and disabled.’

Publishers Weekly

‘Zimler [is] a present-day scholar and writer of remarkable erudition and compelling imagination, an American Umberto Eco.’

Francis King, The Spectator

‘Zimler has this spark of genius, which critics can’t explain but readers recognise, and which every novelist desires but few achieve.’

Michael Eaude, The Independent

The Search for Sana

‘The Search for Sana: a bold investigation of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict … By obliging readers to see the past, [Zimler] illuminates the sources of injustice today … He writes in calm, clear prose adorned by the occasional glistening image like a jewel in a fast-flowing stream.’

Michael Eaude, Tikkunvi

ix

THE INCANDESCENT THREADS

A Novel in the Form of a Mosaic

RICHARD ZIMLER

xi

For the men, women and children forced to spend months and even years in hiding during the Nazi occupation of Poland and other European countries. And for the courageous souls who hid them.

xii

THE MOSAIC PIECES

xv

Maybe none of us is ever aware of our true significance.

—EWA ARMBRUSTERxvi

SHE HAD ONLY ONE CHANCE (2007)

2

3

The Smile

After my mother died, my father would sometimes stop in the middle of the street, tuck his head into his shoulders and swivel around in a slow, suspicious circle, his eyes in search of imminent peril. Dad was seventy-six years old then – tiny, slender and fragile. My wife claimed she still spotted an optimistic bounce in his walk, and my nine-year-old son, George, trying equally hard to cheer me up, said that Grandpa looked like one of those amazing old guys who competed every year in the Boston Marathon.

As for me, every one of my strained and hesitant breaths seemed like a pledge to never accept the injustice of Mom leaving us when she was only sixty-four years old.

The morning after she passed away, Dad brought his clunky cassette player into the kitchen before making his coffee and started listening to an interview she’d done with a Sephardic singer from Istanbul whom she’d befriended. A few minutes later, he found me standing by the back fence of our garden. He’d brought me the bowl of oatmeal I’d left behind in my desperation to get away from my mother’s cheerful voice. As he handed it to me, he said, ‘I’m sorry, Eti, but I won’t be able to go on without hearing your mother every morning. So just be patient with me.’

Three days after Mom’s funeral, while my father and I were walking through the parking lot of his Chase branch, he stopped and peered around, his hands balled into fists.

‘Is it a ghost you’re looking for, or an old enemy?’ I asked.4

‘What do you mean?’ he shot back. His eyebrows furrowed into a V, implying that he found my question nonsensical.

My father has eyebrows like hairy caterpillars. When I was a kid, they sometimes seemed ruthlessly critical of me – especially when I dared to ask him about his childhood in Poland.

‘You seem convinced that somebody dangerous is going to show up around here,’ I told him, trying to sound casual.

‘Around here where?’ he asked.

Rather than say I have no idea, I swirled my hand around to indicate the shopping centre, the bank parking lot, Willis Avenue and the rest of what we normally consider reality.

‘Bah!’ he said, flapping his hand at me as if my version of reality didn’t count for much from where he was standing, but he also shivered, which was when a familiar latch opened inside me and I felt time slowing down, and I made the old mistake of gazing into his big, black, watery eyes for far too long, and when he started gulping for air, tears leaked out through my lashes, and that’s when I started thinking that he really was a marathon runner, and not just him but me, too. I’ve been running behind you, you wayward lunatic, since I was maybe eight years old, I thought, trying to catch up while you look around frantically for a secure hiding place.

In answer to his worried glance, I told him it was the frigid wind that had made my eyes tear. I also tied his woollen scarf around his neck and kissed him on the forehead.

Children of Holocaust survivors learn to hide their irritation early on, of course.

All the time we were in the bank – while he was writing out his withdrawal slip and bantering with our favourite teller, Lakshmi, and drinking a cup of coffee with the bank manager, and making a quick pit stop in the employee bathroom – I kept imagining my father as a panicked eleven-year-old boy standing at the window 5of the tailor shop where he spent his afternoons inside the Warsaw ghetto, waiting for his parents to return home.

As a kid, I used to try to imagine what my father’s parents looked like. From clues he dropped, I ended up picturing them as rumpled, ravenously hungry versions of Edward G. Robinson and – if you can believe it – Barbra Streisand.

Why Barbra Streisand? Dad said his mom used to sing to herself while she cleaned their apartment. He once hummed a bar of her favourite tune to me. Mom later told me its title: ‘Chryzantemy złociste’ – Golden Chrysanthemums.

My father had a sweet baritone, but he only sang when he got a little tipsy or when a synagogue service called for us to join in on a hymn or psalm. It always seemed to me as if Dad believed that showing too much happiness or love in public might get him selected for the ovens – though that speculation of mine turned out to be slightly off target.

The lyrics of ‘Chryzantemy złociste’ begin like this: Golden chrysanthemums in a crystal vase are standing on my piano, soothing sorrow and regret. Occasionally, I find myself singing that verse to myself. My own voice has come to sound to me like a form of defiance – of the way the world has tried to keep my father and me apart.

Dad always grades the public bathrooms he uses for cleanliness, but this time he had no comment. ‘I didn’t notice a thing,’ he said when I asked for his report.

Though he looked a bit weary on shuffling back to me, he regained his energy the moment Lakshmi fetched him a second cup of coffee. He appreciates coffee more than anyone I’ve ever met – even the bank’s stale brew. He licked his lips after every sip as if it were honey – and to make Lakshmi grin at him.

I admired how he charmed everyone, even now, after Mom’s 6death, and also how he jabbered away so knowledgeably with the bank manager, Ed, about the upcoming baseball season, his coat open to reveal his University of Utah T-shirt – a gift from an old friend – unconcerned about its fraying collar and holes.

When Ed gave me the familiar signal with his eyes, I told Dad it was time we let our friends at Chase go back to earning profits.

Just before he and I walked back through the Chase parking lot to my car, I did up the top button of his overcoat, and he smiled at me – a tight, boyish one meant to look sweet-natured and to cover what he was really thinking.

The smile, my mother and I called it.

Did Dad learn how to shield himself with that smile when he first entered the ghetto in November of 1940, or only after his parents were loaded on a transport to Treblinka a year and nine months later? I never asked; I learned to avoid leading him back to the cramped, nearly lightless ground-floor apartment where he lived in the ghetto with his parents.

Dad told me only the vaguest outlines of this story; it was my mother who filled in the details.

After his parents disappeared and until his escape on April 7th, 1943 – for eight straight months – Dad stood every afternoon at the window of Willi’s Tailoring Workshop on the third floor of his apartment house on Koszykowa Street. It afforded him a wide-ranging view over the entire block, and my father figured he’d spot his parents from up there the instant they appeared on the sidewalk.

Throughout the many months he waited, he guarded in the inner pocket of his coat a topaz ring and some other jewellery that his grandmother Luna had given to him; she’d told him to use them as bribes if he ever found himself arrested or threatened by Nazis.

During the first two months his cousin Abe would join him 7in Willi’s workshop, and they’d sometimes play chess. Abe was a wizard at the game. When he was thirteen, he’d played the great Paulin Frydman to a draw. ‘He’d have become a grandmaster, for sure,’ Dad would assure me every time the subject came up.

Then Abe was arrested by the Nazis and taken away.

My father was lucky to escape when he did – the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising started twelve days after he was smuggled out, and his chances of surviving the bloody battles the Jews fought against the Nazis would have been close to zero.

Willi the tailor had already vanished by the time Abe was captured. Once an apprentice on Savile Row in London, he’d insisted on speaking English with my father, claiming that Jews had no future in Poland and that Dad had to learn to speak like a British gentleman if he was going to survive in this world. He’d gone out to buy bread and cigarettes on August 6th, 1942, however, and never returned. Dad was pretty sure that he was one of the fifteen thousand Jews who lined up for a fake bread giveaway organised by the Nazis and forced onto a freight car to Treblinka.

Two weeks earlier, the slender, long-haired, dandyish tailor had handed Dad his scissors and shown him how to cut woollen fabric. Each fabric had its own personality, Willi had told my dad: wool was stubborn but generous, cotton straightforward and honest, linen deceptively complicated but often comic. Then, while Dad watched his neighbour sewing the collar on a shimmering-blue waistcoat that he was making for a friend, my father realised that great skill and beauty resided in his hands, though Dad couldn’t have expressed it that way at his age. When the tailor winked at my father and called him over for a hug, Dad discovered that he wanted to study with him – and follow the same path in life.

If Willi had survived, would he have learned to shield off his 8friends and family with a smile like my father’s? I suppose I could have found out how common such a strategy was by spending time with the handful of leaky-eyed, joke-telling veterans of Auschwitz and Treblinka at our synagogue, but I avoided them; one old Jew stifling my questions about his childhood with his eyebrows and showing me the smile was more than enough.

A Plan Inside the Pain

My father’s great-grandmother, Rosa Kalish, was a famous matchmaker from the Polish city of Garwolin. That was also where Dad was born, but his parents moved to Warsaw when he was just two years old. Rosa’s family name was Zarco. Her ancestors on her father’s side had come from Portugal, she said, which was why she could speak Ladino. And why she had been named Rosa and not Róża. She had a fox-like face and short silver hair. Her hands were affectionate and slender.

Rosa was murdered at Treblinka in May of 1943, at the age of ninety-three. Before her death, her family and neighbours believed her to be the oldest woman in the Warsaw ghetto. And probably one of the smallest, too. Forty-two kilos – that’s what Rosa weighed just before she was picked up by the Nazis. ‘Boy, was she skinny!’ Dad once told me, bursting out with a short, dry laugh that seemed uncharacteristically mean-spirited to me. ‘Her ribs stood out like … like the beams of one of those Roman ships. What’s the English word for them?’

‘Galleons.’

‘Galleons – right!’

When I was at college, a friend whose mother had survived Bergen-Belsen told me that the laugh of my father’s that I described to her wasn’t really a laugh. ‘How could you not know that?’ she shrieked at me, and I had nothing to say to her except what seemed 9like the truth – ‘I guess I was afraid to know more about what had happened to him and his great-grandmother.’

Dad knew her weight because his paediatrician father insisted on giving Rosa a check-up every week to see if he was succeeding in fattening her up with the cheese and schmaltz he requested as payment from his patients.

Putting weight on Rosa didn’t work, my father told me. Although he never told me why, I picked up clues from the sprinkling of stories that he told me about her that she must have offered most of her grandson’s high-calorie treats to the kids in the family – to Dad and his cousins, Abe, Esther and Shelly. Shelly was the only other person in the family to survive the war.

Four months ago, after Dad’s Valium overdose, Shelly told me in a conspiratorial whisper that their favourite meal in the ghetto had been pumpernickel bread smeared with schmaltz. Though Shelly didn’t say that these treats came from Rosa, he implied it when he held his finger to his lips and warned me not to tell my father what he’d said. ‘He’ll scream bloody murder at me if you let on that you know!’ he whispered.

Dad’s father used to summon him up onto the scale just after Rosa, but my father always claimed not to remember his own weight. Still, I know that his ribs must have stuck out like a Roman galleon as well, because I overheard him telling my mother once that when he ate a boiled potato covered in sour cream just after finding refuge in the home of Christian friends on the other side of the ghetto wall, he threw up because his stomach wasn’t used to so many calories.

Though Dad was named Benjamin, after Rosa’s long-dead husband, everyone in the family called him either Benni or – because he was small and slight – Katchkele, which was Yiddish for ‘little duck’.10

Rosa didn’t want to go for a medical check-up every week but she agreed in the end because she realised it helped keep her grandson – Dad’s father – hopeful.

As to why her grandson, whose name was Adam, insisted on weighing her, Rosa told Dad, ‘He’s found a plan inside his pain.’

‘What do you mean?’ my father had asked the old woman.

‘A strategy.’

‘And what’s his strategy?’

‘To keep his grandmother and his Katchkele alive long enough to make it out of here. And it wouldn’t be very nice for us to spoil his efforts, would it?’

Do You Really Think So?

After he retired, my father started studying kabbalah every day with help from a professor of Jewish mysticism at the University of California. Whenever I was over his house, I would sneak into the bedroom and look at the esoteric texts he stacked in rickety towers on his desk and wonder what the hell he was looking for.

The book he always kept on his night table was Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism, by his hero, Gershom Scholem, who had single-handedly revived interest in kabbalah among both scholars and practising Jews in the 1940s and 50s. The text had dozens of dog-eared pages, and so many of Dad’s notes in pencil – and even his tiny illustrations of the mythological beasts that Scholem describes – that I once told my father that he ought to try to publish an annotated version, but he scoffed and said that he had never gone to university and nobody would be interested in his opinions, and in any case his notes were really just for himself.

Dad always lacked confidence in his own intellectual abilities, though Mom always said that he had trained himself to evaluate all her articles on Sephardic music with such uncommon depth 11and insight that she would never have considered publishing one without getting the go-ahead from him.

Once, when Mom and Dad were on vacation in the Bahamas, I slept at their house while on a trip to New York, and I read all his hundreds of notes in the margins of Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism. One particular comment he’d written in blue pencil caught my attention: Do you really think so, Mr Scholem?

The sentence next to that comment read: ‘The long history of Jewish mysticism shows no trace of feminine influence.’

Another of the books I found on Dad’s night table on that visit was Greek Religion by Walter Burkert. My father was always reading about the ancient Greeks. When I was maybe just five or six, he told me that in a previous life he’d worked at the Library of Alexandria.

‘What did you do there?’ I’d asked him. He was walking me to school and we were holding hands.

‘Nothing important – I just kept things neat and tidy,’ he replied, as if it were completely reasonable to think so.

‘Did you like working there?’

He showed me a delighted face. ‘Boy, did I! I could read all the scrolls I wanted, and I was fluent in Greek and Egyptian, and at lunchtime I’d go swimming in the Mediterranean. Warm seawater, pretty women, sun, beer, good books … Eti, I had it all!’

From that brief list of delights, I discovered what Dad’s vision of paradise was. And it sounded pretty good to me, too, but a few days later I realised that the list didn’t include me, and I was upset about that for years, though it embarrasses me now to admit it.

While Dad was in the hospital recovering from the Valium overdose, I’d go to his room and sit on his bed and wonder when he’d be able to come home. One time, I found a second book under his copy of Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism. It was They Came12Like Swallows, a novel I’d recently given him. On the first page, he’d written in Yiddish: Present from Eti. Excellent writing – too good, in fact. After that, in parenthesis, he’d written to my mom: Tessa, I think the author would understand how much I miss you.

They Came Like Swallows was written by William Maxwell. It’s about a young boy whose beloved mother dies in the flu epidemic of 1919. Maybe I ought to have given my father a more cheerful novel to read, but he had told me many times that he preferred tragedies.

‘When I start to sniff a happy ending, I always look for the doorway out,’ was his exact quote.

All I’d Failed to Understand

My mother’s father, Maurice, had come to America from Greece in 1937, when he was twenty-four years old. He was the only grandparent I got to know, since Dad’s parents were long dead and Mom prevented me from seeing her mother, whom she described as toxic.

Imagine leaving home just after completing your master’s degree in music history and never seeing your parents again. All the time I was with Grandpa Morrie – every time he took me to a jazz club or classical concert – I never thought once about the hardships that must have still been throbbing inside his old man’s heart. Or about his terror at having to raise two little daughters alone. These days, there are times when my youthful obliviousness seems unforgivable, but maybe it’s a blessing that kids don’t ever feel the need to gaze out over the length and breadth of their grandparents’ lives.

Once, when I was drawing with my father, he told me that we never saw Mom’s mother because she was a mean person and didn’t want what was best for me.

‘Why not?’ I’d asked him.

He put down his crayon and looked at me, and I could see him 13trying – and failing – to find the right words in English. He lifted me up and sat me on his lap. I must have been about four or five years old. We were in the kitchen at our dinner table.

‘Listen, Eti, your grandmother … I think she got lost and never found her way back home,’ he said, but he spoke in an unsure voice.

Confusion made me study my father’s eyes, because I’d learned I could sometimes find emotions there that he tried to hide from me. This time, I wasn’t sure what I saw, but it might have been distress or fear, because it made me want to stay on his lap for a long time.

‘How did she get lost?’ I asked.

He took a deep breath, which made me think – in the itchy way that insights come to kids – that he wasn’t going to tell me the truth. ‘If I said she was jealous of your mother and Grandpa Morrie, would that make any sense to you?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘She’s angry, baby,’ he tried next. ‘Though that’s not exactly what I mean. It’s more like …’ Dad looked past me, and I didn’t understand that he was looking for a more perfect term, so I turned around to see if Mom was there, but she wasn’t. Neither of us found the right words at the time, or maybe Dad really didn’t want to tell me the truth, though an odd and angry letter I would receive from my grandmother fifteen years later would make it clear what he ought to have said: Your grandmother holds a deadly grudge against your mother.

Grandma’s letter was handwritten on four sheets of light-blue paper, front and back, with her name engraved at the top in gold: Dorothy Spinelli. I received it two weeks after I’d spoken to her on the phone. She said she would be overjoyed to make me lunch at her apartment in Great Neck, on Long Island, but also said that she thought it only fair for me to know her feelings about my mother first.14

At the time, I was studying painting at the City University of New York, and I’d found my grandmother in the Nassau County phone book. The letter she sent me two weeks after our phone call listed a series of injustices my mother had inflicted on her. The first one was, When she was five years old, your ‘oh-so-sweet’ mother refused to eat the moussaka I’d made for your grandfather’s birthday, and she ran out of the room shrieking when I took some on my fork and held it up to her mouth.

‘Oh-so-sweet’ was written inside quote marks, as though I wouldn’t otherwise understand she wasn’t really praising my mother.

Grandma Dorothy had pressed so hard with her pen while writing that sentence – and again while warning me to beware of my mother’s ‘vicious temper and horrid betrayals’ – that she had torn both times through the paper.

To hold a grudge against a five-year-old girl who refused to eat moussaka seemed insane, of course. And vicious temper? My mom had raised her voice at me on a number of occasions when I was little, but she’d never spanked me or humiliated me in any way. Though I thought of calling my grandmother to give her another chance, it seemed a lot safer for me to reply with silence. And she never wrote me again.

Every Friday night, Mom and Dad and I would have Sabbath dinner with Grandpa Morrie at his apartment in the East Village. He lived inside three small rooms that he painted in bright colours to highlight the black-and-white photographs of Mom and Aunt Evie that he hung all over the place, even in the bathrooms. The picture he kept above his bed was of himself and his daughters with his hero, Louis Armstrong, and he’d had it blown up to twice the size of a record cover. In it, Morrie, Mom, Aunt Evie and Mr Armstrong are standing in front of Saul’s Bagels & Bialys, 15where my grandfather used to pick up breakfast every Saturday morning. It is October 24th, 1953. Mom is ten years old and Evie is eight. Mr Armstrong is laughing sweetly while gazing down at Evie, whose lips are pursed and cheeks sucked in. She is making her famous tropical fish face, and, as anyone in my family can tell you, her elbows jutting out are her fins.

Morrie is gripping Evie’s shoulder to keep her from moving, since her tropical fish imitation usually involved swimming around in circles. Louis is holding my mother’s hand.

Mom’s eyes are wary. Her painfully slender shoulders are hunched. ‘I was on the FBI’s Most Wanted list at the time,’ she tells people whenever they first see the photo and ask her why she looked so terrified.

‘Your mother was just crazy shy,’ Morrie explained to me when I asked if Mom had been upset that day. Then amusement widened his eyes. ‘But that changed when she got interested in boys. Thank god for oestrogen!’

Morrie used to play bootleg albums of all the great jazz musicians for me and Dad when we’d visit, though sometimes we’d also watch Mets games on Channel 9. When Mom would join us, the three of them would talk about Richard Nixon, Henry Kissinger and all the other warmongers, as they called them. Their voices were contemptuous. Mom and Dad despised Nixon more than anyone else, it seemed to me. As for Morrie, he never referred to the president by name but nearly always as that Jew-hating fíjo de puta – ‘son of a bitch’ in Ladino. He kept a newspaper on his upright piano of two New York City cops arresting him and Dad during a protest against the Vietnam War. ‘One of my proudest moments,’ he used to tell me.

Grandpa Morrie died of a heart attack when I was twenty-one years old. He was seventy-four. After the funeral, I played in a 16baseball game organised by old friends at a local park, and the first time I came up to bat, I knew I was right where my grandfather wanted me to be.

During high-school baseball season, Morrie used to come see me play as often as possible. Once, when I’d hit a triple down the line in right, I looked up from third base to see him weeping. He told me later that while I was running the bases, he’d realised with growing excitement that our family genes had skipped two generations. ‘Papa was a really fast runner, just like you, Eti. He almost made it to the Olympics in Stockholm in 1912 – in the 400 metres.’

I overheard him once saying to my mom, ‘Me, a near-sighted Greek Jew with bad knees, and I’ve got two gorgeous daughters and Willie Mays for a grandson. Who’d have figured it?’

That remark seems so typical of him – and so generous – that I often think of it when I study the picture of him and me that I keep on my night table. It’s a photograph that my father snapped of us just after a baseball game. All these years later, I can still feel the soft perfection of my blue-and-grey uniform and how it made me want to show off for my family. I’ve put my baseball cap on Grandpa Morrie, and my arm is over his shoulder because it makes him feel proud that I’m taller than him and nearing manhood. His eyes are a bit tentative and embarrassed, since he suspects that a little old Greek Jew might look ridiculous in a baseball cap, though everyone who sees the picture invariably says something like Your grandfather looks so cute. My wife Angie never knew Morrie but came closer to the truth when she said, ‘He looks like he never stopped being a kid!’

I once asked Morrie what it felt like to know he’d never again see the family of his childhood – his parents or his little brother and sister.17

He replied, ‘Every morning I light four candles inside my mind, and I’m aware that it’ll never be enough, but it’s all I know how to do. And I’ve been doing it since 1947, when I began to accept that no one survived.’ He also added in a conspiratorial whisper, ‘The secret I’ll only tell you, Eti, is that sometimes I’d like to blow out the flames, just for a day or two, and forget what happened.’

I questioned how he could talk about missing his parents so easily with me but my dad could never talk about them. ‘Benni lost them too early. He was only eleven years old. Me, I was twenty-four and already a man. I understood what had happened. He didn’t.’

On weekends during the summer, Morrie would take me to the pond in Central Park that’s near Fifth Avenue so that we could sail the little wooden boat we’d made in his apartment. He would puff gleefully on his pipe as we watched the boat make its way across the water.

The pond seemed a world unto itself back then – a sea of possibilities shimmering in the summer sun.

Morrie warned me never to tell my mother he still smoked when he and I were alone. He’d draw a finger across his throat and say, ‘If she finds out, she’ll cut off my head!’

How adult and important it made me feel to have my grandfather confide in me!

Morrie sometimes asked me to draw his portrait when we were alone, and when I was finished he’d sketch me. He’d lean forward and study me with his small, experienced eyes – eyes that suggested contemplation and refinement – and after a while I’d become aware that there was a great deal between us that I couldn’t explain but that made us seem like the only two people in the world.

A couple of years ago, just after Mom was diagnosed with breast cancer, she and I walked all the way up to Central Park and went to the pond where Grandpa Morrie used to take me. I 18almost blurted something out about the sweet smell of his pipe tobacco, and how it used to make me feel protected, but I heard him shout inside my head, Dear God, Eti, don’t you dare tell her! Which made me laugh to myself, of course.

When we finally reached the pond, I discovered – to my astonishment – that it was tiny.

While Mom and I watched two slender little Chinese kids fixing the sail on their tall-masted toy boat, I wondered what else I had failed to comprehend when I was young. And would never now understand.

First Signs

Twelve days after Mom’s funeral and seven days after my return home to Boston, I got a call from Dad’s mailman, Peter, saying that he hadn’t seen my father for a while and that the mail was piling up in the metal box on his stoop. He said he’d knocked on the door that afternoon, but that my dad didn’t answer.

When I called my father, he said, ‘Oy, zat Peter is such a nudnik!’ thickening his Yiddish accent for comic effect – and to conceal his true feelings.

I laughed so he wouldn’t realise how worried I was. ‘So, is everything okay?’ I asked.

‘Hunky dory.’

Dad always loved to use corny American slang like that because it made him feel like he was no longer a youthful immigrant lost in a gigantic, foreign city.

‘Peter knocked on your door today,’ I told him. ‘Didn’t you hear him?’

‘No, I must have been taking a dump or something.’

‘So why aren’t you picking up the mail?’

‘It’s mostly just bills. Who needs that tsuris right now?’19

Dad’s reply seemed genuine, so I said, ‘You don’t have to pay anything – I’ll visit you in a couple of weeks and write out all the cheques – but please just take the mail in so Peter can stop worrying.’

My father agreed to my request without any fuss, but Peter called again three days later and said the mail was still piling up. Worse, Mrs Narayan, Dad’s across-the-street neighbour, phoned that afternoon to say that a young man driving a van had brought two big brown bags into my father’s house that morning. ‘That driver looked frightfully suspicious,’ she told me.

Mrs Narayan uses adverbs like frightfully because she went to a British school in Mumbai and got her degree in political science at King’s College in London.

‘Suspicious in what way?’ I asked.

‘Well, his trousers were too large. And he looked Mexican.’

‘Was he wearing a sombrero and eating a taco?’ I joked.

‘Ethan, my darling, you may laugh if you want,’ she said with regal reserve, ‘but I’m telling you, it all looked very odd.’

I had a drawing class to give in ten minutes, so I thanked Mrs Narayan and waited until I was done with my teaching to call Dad.

‘Did you get a delivery today?’ I asked.

‘A delivery?’

‘Two bags of something brought by a young man who looks Mexican.’

‘Eti, what in God’s name are you talking about?’

‘Mrs Narayan called and she said the delivery boy looked Mexican.’

‘Why is Mrs Narayan calling you? And how the hell does she have your number?’

‘I gave it to her after Mom fell down at home – near the end of her radiation treatments. Mrs Narayan is worried about you.’20

‘I wish everybody would stop worrying so much about me!’ he snapped.

‘Okay, but who brought you a delivery?’

‘He’s a kid from Waldbaum’s. And he’s from Iran. His name is Farid. He’s a senior at Hofstra majoring in psychology. And he’s about as suspicious as matza ball soup.’

‘You’re getting deliveries now?’

‘Why go out in this cold? I could fall on the ice and wake up dead.’

‘But you always liked going to Waldbaum’s.’

‘I liked going with your mother.’

I made no reply; I felt as if Dad had clobbered me over the head. ‘Are you there?’ he asked.

‘I’m here. So, is Farid reliable? We could hire someone to bring you groceries on a regular basis, you know.’

‘Nah, it’s not worth it. I just buy scraps. Who can bother cooking for just one person?’

Would you please stop making this more difficult than it needs to be! I screamed at him in my head. ‘Listen, I’m coming to visit this weekend,’ I said instead. The words just popped out of me. The regret I felt for speaking them was like a corrosive, rusty weight in my chest.

‘I told you, I don’t need anyone checking on me!’ he snarled. But his voice wavered and he seemed close to tears.

‘Yeah, well maybe I need to visit you!’ I shot back.

‘What’s that supposed to mean?’

I almost shouted, My mother just died, or have you forgotten that? Instead, I told him I needed to come down to New York to meet with the owner of the gallery in Queens where I had an exhibition coming up.21

Shelly

Dad’s cousin Shelly was eleven years older than him. He’d been forced into the ghetto when he was twenty years old. After escaping through a tunnel, he fled through the forests of Poland to the Soviet Ukraine and ended up in Odessa, where he boarded a freighter to Marseille, and from there he’d taken another boat to Algiers. ‘I lived out the war offloading cargo ships, drinking cheap wine and fucking,’ he told me while staying with us on the weekend of my bar mitzvah.

Shelly was the first adult who ever spoke to me about sex, and about three years later, when I was a skinny, pimply and unhappy sixteen-year-old, he told me – sitting with me on my bed – that he’d had relationships with both men and women in Warsaw, Algiers and Montreal – ‘And everywhere in between!’ he said with his infectious, big-hearted laugh. He also assured me that anything I wanted to do in bed was just fine, and that I shouldn’t allow anyone – even my parents – to tell me what to do with my cock or ass. He probably thought I was gay, and I wasn’t sure myself, but in the end it turned out I was just hopelessly awkward.

A year later, while Dad and I were visiting him in Montreal, Shelly stayed up late with me one night and got drunk on rum and told me about Claude, a French stevedore he’d fallen in love in Algiers. ‘But the man who really takes my heart,’ he said, thrusting up his hand as if to stop an onrushing bus, ‘is George Bizaadii.’

When he was drunk, Shelly would forget how to form the past tense in English, so he tended to talk mostly in the present.

‘Uncle George?’ I asked.

‘Yeah, boy is he handsome when he is young!’

George was the half-Navajo, half-Jewish artist whose paintings were all over our house. He’d helped Shelly locate Dad after the war. Me and my cousins called him Uncle George. His long-time partner 22was an architect named Martin. We celebrated Passover with them every year at their adobe home on the outskirts of Moab, Utah.

‘You and Uncle George were in love?’ I asked.

‘Absolutely!’

‘For how long?’

‘A few years. That is when we take a boat to Poland and find your dad.’

‘So why’d you split up?’

Shelly fluttered his lips as if he were a balloon losing air. ‘George once said that I speak French, English and Yiddish but not Monogamy. He kicks me out. Lucky for me, I spot your Aunt Julie a few months later, and that is that.’

‘Love at first sight?’ I asked.

‘Absolutely! Julie’s face, it radiates a kind of light. And it still does. What a knockout! And when I sleep with her, it’s as if … well, how can I explain …?’ He lit a cigarette while trying to come up with the right words. In a no-nonsense voice, he added, ‘It’s like this, kiddo, we all know that Julie is smart as a whip, and she has a great sense of humour, and she is the most good-natured person I have ever met. But I’m going to be honest with you. After all, you’re not a little kid anymore. I was young, and I was always ready to fuck, and what I like most – at least at first – is that she has a pussy made in heaven.’

Shelly used the word minette for ‘pussy’ and paradis for ‘heaven’.

‘And just like that, pow!’ he said, snapping his fingers, ‘I have two hungry little girls and a mortgage on a three-bedroom house in the suburbs.’

Shelly offered to take me that night to what he called a swanky cathouse near Mount Royal where I could get anything I wanted, but I was too scared to go with him and he was way too drunk to drive, in any case.23

Throughout my childhood, Shelly would stay with us for two weeks every Christmas, and we would drive up to visit him and Julie and their kids every summer. He seemed like a movie star from the 1940s to me back then, with his slicked-back hair and stunning green eyes.

Shelly would always bring me fancy sneakers as a present, since he owned a sporting goods shop in downtown Montreal.

Shelly’s grandmother – his mom’s mother – had been from Rouen and had taught at an international school in Kraków for nearly twenty years. After moving to Warsaw just before the Second World War, she became good friends with the French cultural attaché and his wife, and that was how Shelly ended up with the papers he needed to make it to Algiers and later Montreal. It was Shelly who also managed to bring Dad to Canada two years after the end of the war, and from there my father made it down to New York, where he began working as an assistant to a fashionable Midtown tailor in the autumn of 1949.

‘I won’t ever apologise to anyone about who I fuck or anything else,’ I once overheard Shelly telling Rabbi Simon, who had performed my parents’ wedding ceremony, in an angry whisper. They’d been conversing in my parents’ kitchen. ‘Not you, not anyone! All my apologies ended in the ghetto!’

We Missed Every Chance

I insisted on visiting my father over the coming weekend because I suspected that his refusal to shop at Waldbaum’s meant that he was hiding some illness that kept him housebound. I drove down from Boston early Saturday and arrived around eleven in the morning. Upstairs, I found a shard of blue porcelain in the hallway. Had a robber broken in? My heart dove toward panic, but Dad was comfortably asleep on his bed. A smashed blue cup was on the floor by Mom’s dressing table.24

The bedroom smelled like a pet shop and books were scattered across the blankets.

It looked as if he hadn’t shaved in a week and his thick silver hair was scattered in wild tufts. The whiskers on his cheeks were white, but they were grey on his upper lip. His head leaned back against two pillows and his mouth was wide open, and he was taking wheezing breaths. Now and again, he’d lick his lips. It seemed as if he might be talking with someone in his dreams.

A book was open on his chest: On the Mystical Shape of the Godhead, by Gershom Scholem. I started thinking that maybe what he had been studying in kabbalah had upset him and made him scared to leave the house. I sat on the end of the bed and started rubbing his feet through the blanket.

Isn’t it strange how we do things before deciding to do them? One minute I was wondering what the hell was going on with my father, and the next I was sitting beside him and caressing his feet and wishing that my mother was around so she could order him into the bathroom for a shower and a shave.

While I tried to nudge Dad awake, I imagined what I’d want to say to him after he was gone, and I decided it would be this: You and I missed every chance to talk to each other about what life was like when you were a little boy in Poland and how you suffered. I wish we hadn’t.

I made him a strong cup of tea, brought it up to him and kissed him on his forehead. ‘Eti?’ he asked once his eyes were opened.

‘Yeah, it’s me. I made you tea. With lemon and honey, just like you like it. I’ll help you sit up.’

‘I was dreaming,’ he told me, gripping my arm.

‘Were you in trouble in the dream?’

‘Yeah, I was in the ghetto, and Rosa was there – your great-great-grandmother.’ Tears welled in his eyes. ‘There was a gigantic wolf 25or dog in the room with us, and he looked like he was starving, and he was going to eat us.’ Dad looked past me and said something in Yiddish in a panicked voice.

‘I don’t understand,’ I said.

‘I think there was a dead wolf on the ground with us, too,’ he continued. ‘Grandma Rosa, she shot arrows at the one that was alive, and the arrows formed this kind of mesh in front of him, so he couldn’t get at us. He picked up his dead friend in his jaws and dragged him up the stairs. He wanted to lock us in the house – to trap us. He had a key hanging around his neck, on a chain. And then … then I woke up.’

He looked at me questioningly, blinking his eyes as if startled by too much sunlight. ‘I’m glad Grandma Rosa was there to protect you,’ I said.

He stared at me in shock, as if I’d understood too much. Then he showed me his smile that wasn’t a smile and apologised for bothering me with what he called my silly memories.

‘I like hearing your memories,’ I said, but I was thinking, How could two giant wolves or dogs be part of a memory? Did they represent the Nazis who’d nearly discovered him in his hiding place on the Christian side of Warsaw?

After I brought Dad a second cup of tea and some toast, I asked him to tell me more about Rosa. I think I may have already sensed – without knowing it – that she held the key to his troubling behaviour.

He furrowed his eyebrows at me. ‘There’s nothing to say,’ he replied.

‘You just don’t want to tell me,’ I told him in a hard tone.

After I reached his doorway, I looked back to see if he would at least show me a little regret, but he had already opened On the Mystical Shape of the Godhead and put on his glasses.26

When I Find It

Dad came downstairs in his blue flannel pyjamas. Around his neck was a bolo tie of the sun god that Uncle George had given him as a Hanukkah present before I was born. The solar disc was made of shimmering mother-of-pearl rimmed with turquoise and made me think of how he’d lived in near total darkness while hiding in Christian Warsaw, much of the time reading by candlelight in a small alcove at the back of a storage room belonging to old friends of his mother, Piotr and Martyna. This was after he’d escaped from the Jewish ghetto in the early spring of 1943. In December of that year, after eight months in hiding, his Polish saviours rolled him inside a rug and took him to a more secure hideout in the countryside, where he lived with an elderly and childless piano teacher named Ewa. She knitted Dad a gorgeous blue pullover that he still hid in his underwear drawer, though I was pretty sure I wasn’t supposed to know that.

‘Hey, how about some banana pancakes?’ my father asked with a big smile.

Whenever Dad was rude or thoughtless to me or Mom, he would make it up to us by cooking us pancakes or French toast, or by buying us little presents, or by being particularly affectionate to us over the next few days. Simply saying I’m sorry was never enough for him.

My heart leapt out toward him, but I wasn’t ready to let go of my anger and didn’t answer. Undeterred, he grabbed a banana from the wooden bowl on the counter and handed it to me. ‘Your job, Katchkele, is to mash it.’

Dad nearly always turned making pancakes into a comedy routine. Sometimes he’d flip one up to the ceiling and miss catching it with the pan on purpose and it would splat on his foot. Mom would always laugh – even if it meant having to clean the kitchen 27floor – because with Dad, clowning around was an important part of his love for her and me. It sometimes also seemed as if she understood things about him that no one else did, and because of that, she could forgive him anything.

I stood next to Dad while he made our pancakes and he gave me pointers about how to cook them evenly. After he breathed in their aroma and faked a swoon, he held the pan up to my nose. ‘Heaven on earth, no?’

There was only a little maple syrup in the jar in the refrigerator and Dad poured it all on mine. He ate his with brown sugar instead.

Such easy and spontaneous generosity made me feel selfish for wishing he would reveal the secrets of his past to me. Isn’t it enough for him to have always tried so hard to make me feel secure and cherished? I’d ask myself, though I knew it wasn’t.

After we’d eaten too many pancakes and while we were drinking the decaf coffee I’d made, he asked me for a cigarette.

‘I haven’t smoked for fifteen years,’ I said.

‘Nobody smokes anymore,’ he said with an ugly frown.

‘I think Shelly still smokes on the sly.’

‘So where the hell is Shelly when I need him?’

‘In Montreal.’ I looked at my watch. ‘It’s a safe bet that at this very moment he’s trying to convince Aunt Julie to hop under the bedsheets with him.’

Dad laughed merrily – kidding Shelly about his sexual appetite was part of our family comedy routine.

I might have tried to throw my arms around my dad and kiss him while he was giggling, but he got up to fetch one of the beanies he wears on his head when it gets cold.

Had he sensed I was about to embrace him?

Dad had often held my hand when I was a kid, and he’d cuddled with me all the time at home, but I remember him kissing me only 28once in public. I’d fallen while ice skating at a pond in Queens and opened a gash on my forehead. I started crying, and he picked me up and ran me to our car. Just before we got in, he kneeled down to my height and dried my eyes, and he held my head in both his hands and told me everything would be all right. ‘Don’t be scared,’ he said, ‘I won’t ever let anything bad happen to you.’ He whispered my name and pressed his lips to mine, and he told me that he loved me beyond the edge of the world. And then he kissed my gash as if his love could heal it. His lips and cheek ended up bloody but he didn’t care.

Neither of us ever mentioned that amazing moment, but I often polished the memory as if it were made of gold.

Now, while Dad was fetching his beanie, I looked in the fridge and found four cartons of Tropicana orange juice, a half-gallon of skim milk, two eggs and some mouldy strawberries. I threw out the strawberries. The only other food I spotted was a can of tuna, two bananas and a limp-looking tomato that was sitting on the microwave.

‘What are you eating these days for dinner?’ I asked as soon as he returned to the kitchen.

‘Try looking in the freezer, Inspector Poirot,’ he replied.

I found nine bags of Libby’s Steam and Go frozen peas. ‘All you eat for dinner are peas?’

He was licking the brown sugar off his plate but paused long enough to say, ‘Don’t knock it if you haven’t tried it.’

‘You need to eat something else.’

‘Says who?’ he said with a scandalised expression.

‘Says me. I’m taking you out for dinner. We’ll go to the Sea Cove.’

‘Eti, the Sea Cove hasn’t been any good since you were peeing in your diapers.’29

‘We lived in Manhattan when I was peeing in my diapers. We never knew the Sea Cove even existed.’

He looked up to heaven. ‘What did I do to deserve a kid who can always argue better than me?’

‘We’ll go to Cactus Taqueria,’ I said. ‘You love their burritos.’

He thought about that. ‘Call them up for takeout. Get me a vegetarian burrito with no cheese and extra hot sauce. I’ll give you money.’

‘You need to get some air. We’ll pick them up together. And you can save your money.’

‘So, did your medical degree from Harvard finally come in the mail?’ he asked with his eyebrows making a stern V.

‘And you need a shower,’ I told him. I held my nose for comic effect.

‘Bah!’

‘And take off those pyjamas. I need to put them in the laundry.’

‘Are you finished with the lectures?’ he asked, showing me a nasty frown.

‘I’ll finish them when you tell me what’s going on.’

‘Nothing’s going on.’

‘Well, what’s with the bolo tie?’ I asked.

‘I felt like dressing up,’ he said defiantly. ‘Can’t I dress up in my own house?’ He looked past me as though enchanted by a memory. ‘When you were small, I used to always wear a suit and tie whenever I’d go out. Those were the days!’

‘You know what, you should put on a really nice shirt – one of the linen ones you made for yourself – and show everyone at the taqueria how handsome you look in your bolo tie.’

‘Nah, I’m tired of being in the world. I’ve been out there,’ he said, flapping his hand in the general direction of the street, ‘for seventy years. When do I get to stay home?’30

It seemed a reasonable query for a recently widowed man to ask, so I backed off. And I picked up vegetarian burritos for the two of us. But after I’d fluffed up his pillows and neatened his sheets that night, I questioned him if he was looking for anything special of late in all his kabbalah books. He was seated on the armchair in his living room, watching a black-and-white movie on TV.

‘No, nothing,’ he answered.

‘I’m not sure I like you reading all the time about angels and demons and spirits, and all that other weird stuff.’

‘Why not?’

‘You’re exhausted. We both are. You need a break.’

‘I don’t see what one thing has to do with the other,’ he said.

‘Look, Dad, if you tell me what you’re looking for, I won’t tell anyone, not even Angie.’

He turned down the volume on the TV and said, ‘There’s this piano player, and he plays only one note, and everybody in his family thinks he’s crazy. And then one day …’

‘No jokes,’ I said, rolling my eyes.

‘Ssshhh! And one day the piano player’s son asks him why he only plays one note, and the piano player, he says, “Everybody else is looking for it, but I found it!”’

Dad looked at me defiantly.

‘What exactly are you trying to say?’ I asked.

‘Isn’t it obvious?’

‘In the Yiddish original, maybe. In your English translation, no.’

‘I’ll know what I’m looking for in my books when I find it.’

Standing High Up on a Cliff

My father refused to leave the house with me even once that weekend, and I don’t think he ever ventured further than his own 31front yard over the ensuing weeks. I insisted that he tell me why on my next visit, which was about a month after my first one, but he just kept repeating to me that he was too tired to participate in the world any longer.

Had he developed agoraphobia? My sister-in-law Mariana was a clinical psychologist in Denver, and she raised that possibility with me when I called her, but she also said that Dad’s grief might simply have sapped all his energy. ‘If that’s the case,’ she added, ‘he ought to recover his vitality bit by bit. But either way, you ought to get him into therapy.’

He isn’t ever going to sit in a room and tell a stranger or anyone else about his life, is what I didn’t tell her. Instead, I thanked her for her help and told her I’d do my best.

In late May, three months and a week after Mom’s death, I had trouble reaching my father on the Friday before I was supposed to come for another visit, this time with my wife, Angie, and our son, George. He didn’t answer the phone all morning, so at about eleven-thirty I called Mrs Narayan and told her where I’d hidden a spare key to his front door.

‘There’s a problem,’ she told me when she phoned about ten minutes later. She was crying.

I felt as if I were standing high up on a cliff and that I’d fall a thousand feet straight down if I made a false move. ‘He’s dead, isn’t he?’ I whispered.

‘No, I thought he was, but he’s not.’ She took a deep breath. ‘I’ve called an ambulance. They’re on their way.’

I sat down because the world had started revolving slowly around me. ‘What happened?’