Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Nine Arches Press

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

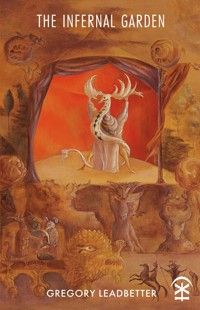

In The Infernal Garden, Gregory Leadbetter's poetry leads us into dark and verdant places of the imagination, the edge of the wild where the human meets the more-than-human in the burning green fuse of the living world. This liminal ground becomes a garden of death and rebirth, of sound and voice, in poems that combine the lyric with the mythic, precision with mystery. Responding to the intricate crisis in our relationship to our planet and the life around us, the garden here assumes a haunting, otherworldly aspect, as a space of loss, grief and trial, which nonetheless carries within it the energies of regeneration and growth. At the heart of this bewitching book is the force of language itself – at once disquieting and healing – through which we are drawn to the common roots of art, science, and magic, in exquisite poetry of incantatory power. "This is heavy-metal poetry, dark and decidedly theatrical." - Jeremy Wikeley, 'The best poetry books of 2025 so far', The Telegraph.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 62

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

The Infernal Garden

The Infernal Garden

Gregory Leadbetter

ISBN: 978-1-916760-24-0

eISBN: 978-1-916760-25-7

Copyright © Gregory Leadbetter, 2025.

Cover artwork: Leonora Carrington, ‘The Juggler’, 1954 © Estate of Leonora Carrington / ARS, NY and DACS, London 2025.

Frontispiece: detail from ‘The Expulsion of Adam and Eve’, wood engraving, Kölner-Bibel, Cologne Bible, 1478 (image: Alamy).

All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form or by any means, graphic, electronic, recorded or mechanical, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Gregory Leadbetter has asserted his right under Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this work.

First published August 2025 by:

Nine Arches Press

Studio 221, Zellig

Gibb Street, Deritend

Birmingham

B9 4AU

United Kingdom

www.ninearchespress.com

Printed in the United Kingdom on recycled paper by: Imprint Digital

Nine Arches Press is supported using public funding by Arts Council England.

Contents

Listen

Raven

Blackbird

Antennae

Long Barrow

Archaeology

Cup and Ring Petroglyph

Inside the Flint

Leap Day

The May

Speckled Blue Egg

Elsewhere

An English Summer

Garden of Lovers

Lady of the Animals

The Cave

Elm Hateth Man and Waiteth

Unenclosure

Wight

Midsummer Field

The Seal

Reading and Writing: A Myth

Syllablings

Ur-

Neume

Temenos

Alchemy

The Glass Head

Devices

Ipsissimus

*Ingwaz

The Infernal Garden

Maschera

Je Est Un Autre

Poor Tom

The Rocking Stone

Wake

Cress

Garden Chair

Riddle

Last Train

The Worst

Unrest

The Smiles

Fall

The Clocks Go Back

Gate

Chimera

Comet C/2023 A3

A Crossing

A Silence

Reedling

The Dark of the Tongue

The Sphere

Gehenna

Orison

From the Invisible

Ros Crux Rite

Fava

Sarcophagus

Dor

Vintage

The Book of Moons

The Speaking Art

Notes

Acknowledgements

About the author and this book

I’ll make a mixture of my tears

for dust that comes from fire

to find in air its fuse again,

the flower’s light its pyre.

Listen

The dead are in my ear again.

What is it they have lost and come

to find? This breath of mine, a wick

alight. I say ‘the dead’, but that

is too precise a term for what

I hear behind my voice. Who

is it in that what that listens

and is listened to, un-echo?

They do not speak as one called

by a cold name at a séance, crude

as fact, nor is their message any

such. They are not even quite

dead. They wear the breath I lit

for a body when I almost heard a hlp m

pinch the air alive. Who’s

there? Remember, there can be

no name, no face on which to fix

their truth, unless it be my own.

But even this, my absent look,

does not disclose the I am that

they make of me. Why don’t they break

the skin of silence? Instead this pressure,

close as weather. Listen is all

they’ve ever said by this, their cypher.

They crave an alphabet. That is

the meat for which they hunger. I pass

from mouth to mouth, and give them it.

Raven

The raven’s call they call a croak

sounds a distance caught in the throat.

Something almost human in voice

sends its tremor from out of sight.

There’s neither crow nor a call to the dead

in the shift of its shape abrading breath.

It is soft as it breaks as a burr in the air

and meets what it makes in the coupling ear.

The bird that is there is as near as a thought

at loose in the skies of human disquiet.

It speaks in the gap between mind and word

where a call across species summons its weird.

Blackbird

They’re common as air on this island,

like the one I hear now, fresh from hell.

The bird has come through: that voice

risen from the descant of fear,

the black yolk of the egg, with its shelter

and its cry to get out. It has come

from the fire at the pit of each feather,

soot that sucks at all light,

flame touched to its eyes, each eye

an eclipse and corona. A bird

wrung from itself, impossible

survivor, whistling from the mouth

of the underworld, returned all

in one breath. Each phrase has its note

of surprise, as if a life after death.

I hear where I too have been

without knowing: a knowledge that loosens

only when stunned. That song

in the silent half of its year

is a harrowing: this sound is the truth

it has won, rare as the dust it renews.

Antennae

I come to look for what isn’t there

and find it in the things that are.

The insect, as if invented

at my skin, that feels with its green

antennae for the auras

between my limits and the runaway sky

is the fae of the grass

at my feet, bare to the ant

and the mist-bodied spider

no bigger than a thought.

Hoverflies still with the air, without

purpose as we know it

yet winged for flight

precise as intention can hold.

Lilac catches me by the throat

and holds me in its speech by scent

that lasts deep into the death

of its bloom. A chainsaw

cuts through a limb

next door. There are trees

to fell, spirits to release by fire

tonight, in pyres that carry

from the pit through the dark

the fume of earth, the smoke

of my self, the fat on the altar

to rouse a dead god.

All this, to fold back into the now

of the sun, the salt

on my neck, a page

to which the letters come

without being human, not quite

to be written but to live

quiet as sleep, fine as the hair

that rises to meet the sense

of their presence, felt as a drawing near

from out of the hide of lawn and leaf

to speak their witness

to the seed of the tongue.

Long Barrow

I

I step from the barrow

where I hid my life

for those still moments

that I stilled the earth

with a sown breath, lit

as a match inside its mind:

listened to my bones suck

at the air that tapered

to the nothing the grave

surrounds. Why go in, except

to find and say some thing

far from myself, but made

as I am made beneath

my days? That word

that cannot be wholly said.

But why to know and speak

that word of all the words

we do not have? To live

within the cleft of thought:

the nothing alive inside

that space, the crossing

between all death. To hear

my ghost in the hollow

ground. Release a voice.

II

I step from the barrow

and let the still breath

of the tomb from my mouth.

Its life in hiding splits upon

the flint of the air, starts

the earth that wakes again

with blinking, breaking light,

cloven with beginning.

Skylarks, loose with song,

are folding time in their high

dallying. They have been

here through all dying.

The red kite rises on its eye

to tilt within the turning

wind, the blessed current

through my lungs. I live,

though nothing but a word

may enter or leave where

I have been: not even that

unless the living gives

something of itself this far

from its life for keeping.

I left a skull in the silent

barrow, to hear its singing.