2,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: neobooks

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Deutsch

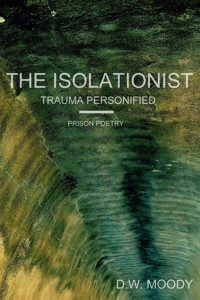

These poems are a collection of traumas and reflections from a man who spent a vast majority of his adult life in prison. This book is for those who wish to see the darkness that can consume a person whole, and the light required to free them; for those who hold onto hope in spite of despair. Trauma is inside us all, do not let it win.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 74

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

D.W. Moody

The Isolationist

Trauma Personified

Dieses ebook wurde erstellt bei

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Titel

INTRO ESSAY

PART I

Catechism of failure

this is a graveyard

beyond repair

Body Language Asylum Waltz

flickering precepts of want and need

Approvals And Denials

ephemeral, in each way

Mask Of Repentance

the price we pay

absence

a healthy dose of not me

Totem of the Chimera

Becoming: Part One – Newborn Becoming Effigist

Becoming: Part Two – Effigist Becoming Soldier

Becoming: Part Three – Soldier Becoming Pessimist

Becoming: Part Four - Pessimist Becoming Corpse

PART II

Miri

the meadow by the lake

at the edge of sleep

Five minutes with my young self

drowning

ocean of jade

lust

Providence

Perseverance

Concordance

PART III

Cathedral of Doubt

branded by distance, infected by love

the abyss

there is no return from here

We don't need our permission

beyond count

crucible of hunger

overcast optimist

drunk on misery

eventide

the Isolationist

a prophecy of virulence

CLOSING ESSAY

Impressum neobooks

INTRO ESSAY

Before dawn, on a cloudy day in the late 90s, (someone whom I had considered) a friend and I murdered two people. In the early morning hours, we took their lives. They did not deserve such a horrific fate. They deserved to live and yet, while they slept, we crept into their bedroom like cowards and killed them. I will not make excuses or offer reasons for why we ended the lives of these vibrant people. That day, I became a willing apparatus of death. In my callousness, I stole the irreplaceable; I destroyed the irreparable, still years shy of adulthood; I took light from a world I did not belong in, shine from a sky I could not see. In my fog, I inflicted trauma beyond articulation. My acts of savagery evoked a violent undulation on the liquid fabric of existence. It exploded from that moment and continues to flow onward, to the moment you read this and forevermore. I did not realize this for many years, even after my sentencing. I failed to understand the all-crushing, ever-flattening gravity of my senselessness. My life was in stasis, my mind rudderless and absent. Within my prison cell, a vile mixture of denial and desperation suffocated me, compelling me to file an appeal. I was searching for a way out from beneath the afflictive mass of guilt pressing its insistent hands upon me—a volley in the darkness I did not deserve. In the early 2000s, I won on a technicality. Hope blossomed its fragile possibilities like expectant wishful petals begging for confirmation of the sun’s touch. I returned to court, confident freedom was just over the horizon. It was not. The sun’s light was mute—the flourishing died.

Later that decade, after a second trial and conviction, I realized my life was over. I began to give up. I looked around at the depressing austere grayness of walls and buildings and fences and thought, “I will die here.” I looked at the anonymous deadness of the faces of the men around me and thought, “I am them now,” and when I saw my reflection in a mirror, I thought, “I am dead, too.” I began to unravel, to succumb to the septic spiritual abyss of complete, existential forfeiture. If I had nothing to live for, why live? Dissolving images of collapse merrily danced in the falling ruins of my disassembling mind. Color no longer came to my eyes. Life no longer felt alive. I was in need of something—anything. One evening, on the way back from the chow hall, a friend asked me how I was.

"l feel like shit,” I responded. We both stopped walking. The harsh California sun bore down its summer grudge on our foreheads, in our eyes, blinding us.

“Why?”

“Because I’m in prison for the rest of my life, dude; the fucking state took my life,” I said, scoffing—he must mad to ask such a stupid question.

He paused, unperturbed by the venom in my response, “Well, whose life did you take?”

It felt as though he slapped me. “What?” I sputtered, taken off-guard.

“Stop lying to yourself.” His face was adamant stone.

“I…I don’t know what you mean,” I was ashamed.

He sighed, seeing my distress, “If you keep believing you did nothing wrong, nothing will change. These walls will continue to draw in closer and the suffocation of your suffering will continue to grow until it bends you in half and breaks you. My advice? Just be honest with yourself. Accept who you are. Accept what you did, and go from there.”

He gave me a small, reassuring smile, and patted my shoulder as he moved on. I stood there for some time considering his words, until the tower guard interrupted my reverie with a firm suggestion I “keep walking.”

My friend will always remain in my heart. His simple wisdom and guidance changed my life in countless ways. It did not happen immediately, though. I did not wake up the next morning a new man, willing to bear the burden I owed, but I started on a different path, a route of self-discovery and responsibility. Once I defeated my built-in obstacles of denial and pride, I started to create connections, linking causalities and realizing the effects my violent acts had on all those involved. I found by imagining trauma as a thing—a creature—I could more distinctly comprehend what it and its consequences mean. I sought to give trauma a from, a shape, a body—a way to show its pervasive ugliness and abiding cruelty and as a way to identify it, perhaps one day even destroy it.

The title, “The Isolationist: Trauma Personified,” builds on two fundamental concepts: 1) isolation created and perpetuated by traumatic experiences, and 2) trauma itself as a deteriorative mechanism of psychological dysfunction. While the focus is on trauma’s effects, isolation is an environment where trauma thrives. Isolation, both voluntary and imposed, creates an atmosphere of helplessness, and a sense of emotional claustrophobia. An isolated person may feel free, unrestricted by obligation, societal norms, or moral expectations, but that freedom exists within a delicate bubble. Surrendered or stripped, the loss of control in a person’s life has the power to eat away at their wellbeing. I do not mean isolation as a form of personal time or respite from the daily grind. Isolation, in this context, represents the willful or forced separation from the healthy forms of communication we humans crave. I realize the quietude of seclusion allows people to process things—I acknowledge the beneficial aspects of privacy. This is not that. The Isolationist is the incarcerated perpetrator, lost in the twisted, one-dimensional, mindfuck maze of physical imprisonment and mental servitude. The Isolationist is the fear-violated, terror-stricken sufferer, cautiously peering out at the monstrous realm lurking beyond locked curtains, fettered doors, and indentured eyes. Trauma creates isolation. Isolation is trauma.

Trauma Personified not only deals with seeing trauma as a physical entity, something that one can describe or define, pictures in a roll of film detailing its face, its form. It also represents the infinite range of consequential effects trauma inflicts on people and how people change—how they distort and mutate—in response to it. By separating trauma, showing it as a weaponized product of the act of hurting oneself and/or others, the lasting impact and deformations in both the victimized and victimizers, seems to make more sense (to me, anyway). Consider images of survivors destroying what they love when their heartache becomes unbearable—thrashing about paralyzed, confusion tolling in their bludgeoned ears, viper fingers puncturing their chest, wresting a pulse from an emptiness in the abandoned torso their minds assume still exists. Thinking about how my actions caused such agony, forever damaging and perverting people’s lives, is the impetus for my determined desire to seek understanding. The personification of trauma helps me to witness and comprehend the reality of my actions—their effect on those I hurt, myself included.

I can’t tell you what these poems really mean beyond what they tell you themselves. The meanings are surely endless, and rightly so. Poetry is intense, and lovely, and requires commitment from both sides—the author undresses for them, revealing vulnerabilities and insecurities and the reader places themselves next to them (if they choose), in similar shoes, moments. That connection, when empathy binds them together, is one of the many achingly beautiful powers of writing—across space, across time, two people can connect and share something meaningful (or one would hope). I am well aware of how convoluted my imagery and language can be, and I made the choice long ago to permit it to flourish without restraint. I only hope my words inspire the reader to feel something. Pain, joy, sorrow, anger, hope; whatever they feel, I want it to be genuine.