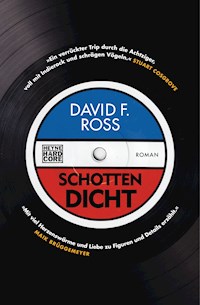

7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Serie: Disco Days

- Sprache: Englisch

Bobby and Joey's new mobile disco business seems like the answer to everything, until they lock horns with the local gangster … First in the critically acclaimed, hilarious and heartbreaking Disco Days Trilogy, by one of Scotland's finest writers. ***Longlisted for the Authors' Club First Novel Award*** 'This is a book that might just make you cry like nobody's watching' Iain MacLeod, Sunday Mail 'Ross creates beautifully rounded characters full of humanity and perhaps most of all, hope. It will make you laugh. It will make you cry. It s rude, keenly observed and candidly down to earth' Liam Rudden, Scotsman 'Warm, funny and evocative' Chris Brookmyre –––––––––––––––––––––––– Early in the decade that taste forgot, Fat Franny Duncan is on top of the world. He is the undoubted King of the Ayrshire Mobile Disco scene, controlling and ruling the competition with an iron fist. But the future is uncertain. A new partnership is coming and is threatening to destroy the big man's empire... Bobby Cassidy and Joey Miller have been best mates since primary school. Joey is an idealist; Bobby just wants to get laid and avoid following his brother Gary to the Falklands. A partnership in their new mobile disco venture seems like the answer to everything. The Last Days of Disco is about family, music, small-time gangsters … and the fear of being sent to the Falklands by the biggest gangster of them all. Witty, energetic and entirely authentic, it's also heartbreakingly honest, weaving together tragedy and comedy with an uncanny and unsettling elegance. A simply stunning debut. –––––––––––––––––––––––– 'Crucially Ross's novel succeeds in balancing light and dark, in that it can leap smoothly from brutal social realism to laugh-out-loud humour within a few sentences' Press & Journal 'More than just a nostalgic recreation of the author's youth, it's a compassionate, affecting story of a family in crisis at a time of upheaval and transformation, when disco wasn't the only thing whose days were numbered' Herald Scotland 'There's a bittersweet poignancy to David F. Ross's debut novel, The Last Days of Disco' Edinburgh Evening News 'Full of comedy, pathos and great tunes' Hardeep Singh Kohli 'Dark, hilarious and heartbreaking' Muriel Gray 'Captures the time, the spirit … I loved it' John Niven 'If I saw that in a store I would buy it without even looking at what was inside' Irvine Welsh 'Like the vinyl that crackles off every page, The Last Days of Disco is as warm and authentic as Roddy Doyle at his very best' Nick Quantrill

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 390

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

For Elaine, Nathan and Nadia

‘Sneak home and pray you’ll never know, The hell where youth and laughter go.’

from ‘Suicide in the Trenches’ by Siegfried Sassoon, 1917

CONTENTS

PART I

A TIME FOR ACTION

‘Now that the official figure for unemployment has exceeded three million, is the Prime Minister proud of the fact that she has brought so much despair to so many families in the United Kingdom? Is she proud of the fact that she and the Government have created more havoc in the British economy than the German High Command in the whole of the last war?’

Dennis Skinner, MP for Bolsover Prime Minister’s Questions, January 1982

1

A MAN ON THE EDGE

24TH JANUARY 1982: 10:23AM

‘Bobby Cassidy was a man on the edge. Monaco was his kinda town …’

As experiences go, this was a highly unusual one. He had always imagined driving at ridiculous speed through the Nouvelle Chicane with James Hunt and Gilles Villeneuve visible in either wing mirror, unable to pass. But now that it was actually happening, Sean Connery’s commentary – Where was that actually coming from? – lent the whole thing a strange and distinctly surreal air. And it was becoming much weirder. Attempting to keep his full concentration on the tight, twisting track with all of its ludicrous hairpin bends and various urban distractions – Was that really Sally McLoy from Hurlford waving at him from the balcony of the Grand Hotel, topless, with those massive tits jiggling away like jellies in an earthquake? – he was troubled by the fact that he couldn’t recall how he got here.

With three million on the dole and the numbers growing by the day, how had he actually become a racing driver in the first place? He couldn’t remember the interview, or even filling in the application form. How many races had he completed? Had he met and been interviewed by Murray Walker? Did he still live in a two-storey, terraced council house at 13 Almond Avenue, Kilmarnock, Scotland, Europe, The World, The Universe (school jotters … old habits die hard) with his mum, dad, sister Heather and prodigal elder brother, Gary? And most disconcertingly, why did he now have three arms?

‘Shurelyshome mishtake …’ 007 was beginning to really irritate Bobby now.

‘Shut the fuck up, Sean. I’m tryin’ tae fuckin’ drive here.’

As he came round the sharp corner at Portier and headed towards the famous tunnel at 180mph, Bobby caught a glimpse of his reflection in the glass barriers surrounding the circuit. The red-and-white McLaren looked like a massive fag packet on wheels. A horizontal line of piercing spotlights caused him to lift his left hand off the tiny steering wheel and up to shield his eyes. As his hand reached his head, two conflicting realisations dawned on him. First, he wasn’t wearing a fucking helmet, and second, the third arm wasn’t his. It belonged to a woman sitting in a bucket seat behind him. And not just any woman; it was the right arm of the lovely Sally James from Tiswas, and she was starting to fondle his cock.

‘Sean, big man, we’re no’ in fuckin’ Kansas anymer …’

He awoke just in time. It wasn’t Sally who was gripping his hard-on. The third arm belonged to Bobby’s elder brother, Gary. That the two were lying in a top-and-tail manner suggested either pre-arrangement or that somebody more responsible had placed them that way. To Bobby, whose recognition of environment and understanding of context was currently diminished, the latter of these two scenarios offered only slightly more comfort.

Bobby retched at this thought. He pulled back instinctively and, amazingly, Gary didn’t stir. If Bobby was careful and composed, he could still get out of the situation with his dignity intact. The World Championship dream over for another season, he swiftly but delicately eased his brother’s hand away from his dick, then Bobby slid himself out of his own single bed and onto the pile of discarded and dirty clothes that lay adjacent. Gary moaned a bit, but didn’t wake up. Bobby had to work hard to stifle an attempt by his stomach to empty its contents right there and then. He edged open the door to his room enough to squeeze through and then made his way along the ten feet of hall to the toilet – arse cheeks and sphincter working overtime.

As he reached the sanctuary of the small bathroom, a new and equally unpleasant sensation began. Motörhead had set up their gear inside his skull and were starting rehearsals for a forthcoming tour.

‘Let’s turn it up t’ a hard fuckin’ eleven, lads,’ said Lemmy. ‘Wake this stupid cunt up proper.’

This rapidly grew into a headache the like of which Bobby could scarcely remember. Worse than when he got his head wedged in old Doris Peters’ garden fence when he was eight. Having squeezed through to nick apples from her tree, his head had got stuck on the way back out. He’d only been in the garden for about twenty minutes, but either he’d grown during the robbery, or He’d tried to leave the scene via a smaller opening than the one Gary and his bastard mates had forced him through on the way in. The pain from having Gary drag him out by the legs had lasted about a week.

He sat on the toilet pan like the famous Rodin figure for around twenty minutes. What a fucking state to get into, he thought. He hadn’t moved since forethought had wisely prompted him to open the small top-hung window just before the deluge had begun. His legs were numb from lack of circulation caused by severe buttock clenching in the early stages. Thereafter, he thought fuck it. It sounded like the Brighouse & Rastrick Brass Band tuning up but it was less effort to just leave the sluice gates open.

The cistern – temperamental at the best of times – had given up the ghost around flush six. By the time Bobby felt sufficiently empty to attempt standing, Motörhead was still thrashing away. As he tightly gripped the towel rail, holding on for stability like an OAP, they’d at least decided to try out a few unplugged acoustic numbers. Bobby allowed himself a glimmer of a smile at this ridiculous analogy.

‘Thanks Lemmy, ya manky, wart-faced bastard,’ he whispered at the vaguely familiar image staring back at him from above the avocado-coloured sink.

What the fuck had occurred last night? He’d had a few mental hangovers before in his short career as a ‘drinker’, but, Jesus Christ, this was crazy. He couldn’t remember getting home. Truth was, he couldn’t even recall going out in the first place. All he knew for certain was that Gary would be central to the reasons behind his amnesia. A pain in his lower back was now also beginning to make itself known.

‘Fuckin’ hell, you. Get a shift oan, eh?’ The gruff, croaky voice jolted Bobby. It had come from the imposter who had recently been trying to ease Bobby’s penis into fifth as he accelerated towards La Rascasse.

‘Ye’ll never believe the dream ah’ve just had,’ it said.

The bathroom door was now opened to the maximum its chain-lock would allow. Harry – Bobby’s dad – had fitted it following his sister’s impassioned pleas for a bit of privacy following her first frightening steps on the road to womanhood. There hadn’t been a working lock on the bathroom door for around ten years. Rather than get the right one for the situation, Harry had rooted around in his shed and fashioned a temporary solution from an old padlock. It had now been temporarily keeping unwanted visitors at bay for nearly fourteen months.

‘Ah was in disguise,’ declared Gary, his ferret-like features pressed against the two-inch gap like Jack in The Shining.

‘Dressed up as the Phantom Flan Flinger, so ah was. Sally James comes ower, aw coy an’ that – an’ mind this is aw live on fuckin’ telly, Saturday mornin’ anaw. So she tells everybody, “It’s time the Phantom was unmasked”.’ Bobby gagged.

Gary’s face was now pushed so far into the gap that he looked distorted – like a Picasso, with both eyes on the same side of the head.

‘Whit the fucks that smell? Izzat you, Boab? Fur fucksake, yer no deid in there, are ye?’ Gary sniffed the putrid air several times before continuing.

‘So, as ah was sayin, ah’m aboot tae get unveiled on live telly. But instead of takin’ the cape off, Sally fuckin’ reaches inside it, an’ starts wankin’ me off! Fuckin’ mental, man.’ Gary paused to maximise the effect. Bobby was astonished that they had both been dreaming about the same person.

‘Wan ae thae dreams yer absolutely fuckin’ convinced is really fuckin’ happenin’.’ Gary pondered again, inhaled deeply and carried on.

‘Then, just as ah’m getting close, she fuckin’ stops … leavin’ me hingin’.’ A third pause.

‘So fuckin’ hurry up an’ get oota there, tae ah finish masel off.’ A few more sniffs.

‘Unless you want tae do it, that is …?’

‘Ah was fuckin’ kiddin’, for Chrissake. Ye didnae need tae spew aw ower the door. There’s nae way ah’d av been letting you anywhere near ma knob. Ah don’t even care that yer a fuckin’ bender … it’d still be like … incest or something.’ Gary was enjoying taunting his younger brother.

Although he could have done without it on this particular morning, Bobby was generally glad his brother was home again. He could be a total cunt at times but, on the whole, he’d always looked out for Bobby. He had often taken the full brunt of Harry’s anger for things that were actually Bobby’s fault.

Bobby lifted his head away from his hands and looked around the room. He still felt as if he was part of a slow-motion replay of incidents that had happened earlier. He watched his elder brother’s freckled and impressively muscular frame disappear into the adjacent kitchen. Outside, it was a beautifully crisp late-winter morning: blinding low-level sun and sporadic vapour trails of breath from people out walking. The view from the dining table made Bobby feel slightly better. Regardless of how bad they are, hangovers eventually pass. He looked over to take in his parents’ newly decorated living room with its smart woodchip wallpaper ‘painted in mongolia’, as his mum Ethel had demanded. (Bobby called his mum Mrs Malaprop, and while the rest of the family found this highly amusing, the joke was lost on Ethel.) As far back as Bobby could recall, his mum had always been a bit brittle. When he was little, there were regular tense arguments between his parents. Usually they involved Gary. They had become fewer in recent years but her emotional fragility was the apparent legacy.

Bobby looked intently at the picture of a small boy that was hanging above the three-bar electric fire to the front of the room. It was a painting but not an especially good one and most certainly not an original. At least ten other people Bobby knew had the same painting positioned in a virtually identical location in their houses. Despite this, there was an undeniably hypnotic quality to the image. Years ago, when she first got it, Ethel had told her daughter that it was a painting of Gary when he was little. The track of a tear that wound its way down the chubby little cheeks came from large, blue, turned-down eyes, just like Gary’s. It wasn’t ever explained why someone had painted a picture of Gary while he was in such a state of distress. Nor why his parents had then framed it and hung it in a position of such prominence. Familiarity had rendered her mystification obsolete over the years, but neither Bobby nor his sister had ever been able to look at the picture without thinking about Gary. Especially in the months after he had suddenly left home and headed for London.

The ‘crying boy’ bore no resemblance to other members of the Cassidy family. Neither did Gary. Numerous family photographs were arranged around the principal room of the Cassidy home. On the sideboard; on top of the bloody piano that Harry had ‘rescued’ from the school where he now worked as a janitor; on the sills of the two windows that looked out onto the front and rear gardens; on the massive wooden cabinet that housed the television – for so long, the dominant voice of the household. (When it ‘spoke’, everybody listened.) Gary appeared in none of these photographs. Bobby hadn’t really thought about this before. Gary had always just seemed to be generally absent; a bona fide black sheep. Now, though, with him back home and a real air of détente finally existing between his brother and his father, Bobby found this absence from family events quite strange.

The door of the kitchen opened and the tinny sound of Soft Cell drifted through it, followed by Gary. He was carrying a tray by its large wicker handles. Arranged carefully on the tray was, by Cassidy standards, an extraordinarily decent breakfast. A plate full of toast – carefully buttered and sliced diagonally, continental style; two boiled eggs – one already decapitated – sitting snugly in comedy egg-cups; a pot of tea encased in one of Ethel’s knitted and badly fitting woollen cosies; and two cups – one plain white and the other welcoming the drinker to Blackpool – made up the ensemble. Gary wasn’t finished though. The giveaway smells of bacon and sliced sausage made this whole exercise even more impressive, considering Gary’s former Olympian levels of laziness. Maybe the Army had done him good after all. Bobby shuffled about uncomfortably in his seat. He had picked the one that faced the rest of the room only because the base of his back was still sore and its solid canvas back was more appealing than the four hard-panelled chairs that sat around the circular table.

‘Some night, eh boy?’ said Gary, the lean, bare-chested Scots Guardsman.

‘Ah don’t ken. Canny fuckin’ remember anythin’ … an’ ah really mean anything,’ said Bobby, still contemplating which parts of this greasy feast set before him might stay the course following consumption.

‘It’s yer eighteenth! Fuck’s sake, Boab, yer no supposed tae remember anything. It’s a well-known fact. Like yer stag do … or the ’60s.’

‘Is it fuck! Ah don’t remember the ’60s cos’ ah was a wean, no because ah was pished. When did we go out?’ Bobby tried to turn the focus to questions that would hopefully prompt small fragments of recollection to return.

‘About nine in the morning,’ Gary said proudly, before adding, ‘on Friday.’ Bobby’s face first recorded emotions of surprise, then shock, then shame and finally – as Steve Wright wished everyone a pleasant Sunday from the kitchen – resignation. A whole day (and night) of Bobby’s life had gone AWOL. He asked if they had gone to the Kilmarnock v Hearts game on Saturday. Gary nodded, his soldier’s mouth full of toasted equivalents. Bobby enquired if they had gone to Casper’s Nightclub at the Cross.

‘Friday … and Saturday tae,’ Gary replied.

‘Where the fuck did we stay on Friday night?’ Bobby tentatively asked, not entirely sure if he was prepared for the answer. His head was now firmly back in his hands.

‘Picked up three wee lassies fae Galston … went back tae theirs for a party, ken whit ah mean?’ said Gary with a salacious wink.

‘What, just the two of us?’

‘Naw,’ said Gary. ‘Thommo was wi’ us. How can ye no remember any o’ this?’

Gary was suddenly aware that Bobby was staring transfixed at his left arm. He was particularly focused on the tattoo on its upper part, running from shoulder blade to just above the elbow. The dark-blue ink on its pale canvas looked a bit like a police badge, but with the words ‘2nd Battalion’ above the crest and ‘Scots Guards’ below it. The crest lay over a bayonet that had a serpent coiled loosely around it. Sensing the question forming slowly in his brother’s head, Gary stood up to break the spell. Bobby looked down at his bare feet, through the absurd glass dining table his mum had recently badgered Harry into buying. All the Cassidy males had simultaneously thought the same thing the first time they saw it: A glass table! How can you rearrange your balls and give yourself the occasional secret wee fiddle when you’re sitting at a fucking glass table?

Ethel’s justification was that it would make the room appear much bigger than it was. Harry considered this to be a typically female attitude: looks over function.

At this precise moment, though, the table’s permeability wasperforming a valuable function. It permitted sight of a series of numbers written on Bobby’s right foot. While not opening an immediate portal into his Lost Weekend, it was nevertheless a clue, since, on closer inspection, it was obviously a phone number. With Gary playing the cunt, it was apparent that he was going to have to piece this mystery together himself.

The front door opened and, a full thirty seconds later, closed again. Gary and Bobby stared at the closed door separating the entrance hall from the room they were in. It opened slowly and before either could see him, Harry announced, ‘It’s bloody freezin’ out there.’

Harry had returned from a walk to pick up the Sunday papers – a journey he took and enjoyed every Sunday morning, although this particular morning’s jaunt had taken longer than normal. Harry had bumped into Stanley May, who had felt the need to impart his own second-hand knowledge of Harry’s sons’ activities over the last forty-eight hours.

‘So you two clowns seem tae have made a right arse o’ yersels then.’

With these words from his father, Gary silently took his leave, pulling a Kilmarnock FC jersey from the radiator as he went. Harry watched him from the other end of the long, narrow room. Harry was of average height and the stereotypical outline for a working-class male in his late forties from the west of Scotland. But, silhouetted against the bright sunlight from the window behind him, Bobby thought he looked like the Michelin Man.

Harry nodded towards the other window behind Bobby, where wisps of smoke betrayed Gary’s current location. ‘Ah suppose he was responsible?’ It was more statement than question.

‘Ach, ah dunno. Ah can’t really remember much. Ah don’t think ah can really blame Gary though. No this time at least …’

‘That’ll make a change then,’ mumbled Harry as he unfolded the Sunday Mail in the comfort of his armchair.

‘Gie him a break, Dad. He’s been like a different guy since he came back fae England.’

Harry did have to concede that the Army seemed to have made a decent person out of Gary, and while he didn’t quite extend to pride, Harry did now have a modest foundation of respect for Gary.

‘So anyway, Dad. He’s away back tae Wellington soon. Ah think you should maybe go out for a pint wi’ him. Whit dae ye think?’ It was unnerving Bobby to be talking to the back of his dad’s balding head, but he continued nonetheless. ‘Why don’t ye take him tae the Masonic next time yer goin’ doon?’

No response.

‘He kens Stan and he kens Desi O’Neill tae. It’s no like he’d be sittin’ there like a spare pri … part in the corner.’ Bobby still found it awkward to use foul or coarse language in front of his parents, unlike his best mate, Joey Millar, who positively relished the opportunity.

‘Is there no somethin’ on the night?’

Still no response. The younger man sighed.

‘Look Bobby, jist leave it eh, will ye? Things are better wi’ him an’ me. That’s enough for just now.’ Harry was in no mood to expand. He put down his paper, got up and went over to the television. Having flicked quickly through the three channels he settled on Farming Outlook.

‘Did ye get me the Sunday Post, Harry?’ Ethel’s wavering, high-pitched voice floated through the same door her husband’s had twenty minutes earlier.

‘Aye.’ There weren’t going to be any long conversations involving the main man of the house this morning.

Ethel strode towards the kitchen, pausing only to address Bobby. ‘When did you two get in?’

‘God knows.’ Bobby was aware he’d need to get up from the chair soon or face a grilling, but he had a real concern that his legs wouldn’t support him.

‘Bobby, put a shirt on when yer at the table.’

This prompt from his mum was enough to make him move. More focused interrogation would surely follow if he didn’t.

‘Bobby, there’s blood on ma seat covers!’ Ethel had come back in from the kitchen and spotted a small red stain low down on the beige hessian.

‘It’s no me, Mum. Ah’m no bleedin’.’ proclaimed Bobby, as he slowly spun around trying to examine himself.

‘Whit’s that oan your back? Right doon low. There,’ said Ethel, squinting.

‘Ah can’t see anything. Where?’ Bobby was still pirouetting.

‘It says something about a H-E-A-R-S-E,’ said Ethel. ‘Hang on. Ah need to go an’ get ma glasses.’ Harry watched Ethel disappear upstairs to retrieve her glasses from her bedside table and then got up to take a look, already suspecting the worst.

‘Ya bloody eejit! You’ve got a fuckin’ tattoo that says “I TAKE IT UP THE ARSE” …’

‘Eh? Aw fuck! Away ye go!’ Bobby’s shock at the tattoo being the source of his back pain made him temporarily forget to whom he was speaking. ‘FUCK! Is that all it says?’

‘Hey. Mind yer language, and naw, that’s no everythin’.’ Below that there’s a line sayin’ “THIS WAY FOR A GOOD TIME”, an’ then there’s an arrow pointing tae the crack o’ yer erse! For fuck’s sake, Bobby, that’s a real bloody tattoo! That’s no washin’ off!’

Split between hunting Gary down and avoiding his mother’s return, Bobby headed for the back door. Needless to say, his brother was long gone.

‘Fuckin’ bastard, Gary,’ mumbled Bobby, as he pulled a white Adidas T-shirt – Gary’s, fuck him – from the line and pulled it on to cover the lightly bloodied artwork. It was bitterly cold and hung like frosted cardboard, having been left out overnight.

‘Where’s Mum?’ said Bobby to Harry, who had joined him in the crisp, clear air of the garden.

‘Sadie Flanagan’s at the door. She’ll be there for ages. Yer bloody lucky, boy. She’ll have forgotten by the time they’re by bletherin’.’

Father and son sat on the damp timber bench. They stared out across the garden towards the school where Bobby intermittently showed his face as a sixth-year student, but where Harry went every weekday throughout term time, and the odd Saturday.

‘What are ye doin’ wi’ yer life, son?’ Harry had posed this question many times to his middle child – mostly over the last five months and always with no tangible reaction.

Bobby shrugged. He was always irritated by this line of questioning. He had just turned eighteen. The ink on the cards in the living room had barely dried. He just wanted to fanny about. When his dad used that term, it was with disdain. When Bobby said it to Joey Miller, it sounded aspirational.

Joey was slightly younger than Bobby. Not eighteen until October, Joey could be really intense and the lassies thought he was a bit strange, verging on creepy. A lot of them called him Jeeves, because he always seemed to be in Bobby’s shadow, and that really irritated both of them. But Bobby saw the other side – Joey was really witty, heavily into music and completely on the same wavelength as Bobby was. Joey wouldn’t have gone to the Killie match. Bobby knew that much. Joey was a Rangers fan, but he’d at least grown up on the south side of Glasgow, so he was entitled. Kilmarnock was full of fucking Old Firm glory-hunters and Bobby hated all of them.

‘What are ye thinking about after leavin’?’

Bobby’s protracted hangover made it feel like he was hearing his dad from underwater. It wasn’t a good feeling.

‘Are ye listenin’ tae me?’ Harry shook his son’s shoulder.

‘Och, Dad, ah dunno. Ah just …’

‘Just whit? Ye’ll need tae dae well wi’ yer English this time if yer goin’ tae university after the summer.’

Bobby couldn’t bring himself to admit that he’d virtually given up on the English higher. His prelim only a few weeks earlier had been a disaster. His mark had been of a level that only Norway’s entrant for the Eurovision Song Contest would’ve considered acceptable. He’d concealed this from both parents so far, but truth was he was heading for expulsion. The Beak had already warned him twice that if he was asked to leave English, he’d be out of school altogether. This situation also applied to Joey, although maths was his particular nemesis. Bobby was fully aware of the creek into which he was drifting – and also the paddle that he had dropped overboard about half a mile back. The last thing he had on his mind now was to jump in, swim back and retrieve it. Fuck that. If the waterfall was just around the bend, he’d continue just to drift towards it, lying back and soaking up some rays en route. Waterfalls are way more exciting than fucking creeks.

‘Look Dad, I’m sorted. Joe and I are gonna start up something. Just don’t ken whit yet.’

‘Jesus Christ, Bobby, he’s the same as you! If brains were dynamite, he widnae have enough tae blow his nose.’ After he’d said this, Harry felt a bit guilty. Joey was undoubtedly clever – he used loads of big words that Harry had never heard before. Harry didn’t mean that Joey was stupid; he meant that he was perhaps the most lazy, unmotivated person in the Northern Hemisphere. He just couldn’t think of an appropriate gag to illustrate that.

‘We were thinking about something tae do wi’ music,’ said Bobby, with enough optimism to inflect the tone.

‘Any ideas then?’ prompted Harry. ‘Record shop? Studio work? A band? A&R …?’ There was a softly sarcastic edge to Harry’s promptings, but it was concealed enough to avoid his son’s impaired senses detecting it.

‘Naw. We can’t play anythin’,’ announced Bobby, as if this was totally new information for the older man. ‘We were thinkin’ more along the lines of DJ-ing.’

Harry held his Embassy Regal packet between the thumb and forefinger of his left hand. He had no option – a couple of years ago the other three digits had been sliced off by a loom in the BMK Carpet Factory, where he had gone after leaving school. With his other hand, he pulled a cigarette carefully out of the newly opened pack of twenty. Bobby watched how effortlessly his damaged hand performed the lighting of the cigarette with a Swan Vesta. He genuinely admired his father for the way in which he had coped since the accident. There had been no anger, no bitterness; simply an acceptance that it was a big pothole in life’s bumpy road that he hadn’t been able to swerve. Initially, Bobby hadn’t been too enamoured that his dad’s only offer of employment following his recuperation had been as a janitor at the school that Bobby attended. But Harry was a well-known and well-liked guy around New Farm Loch, and, as a consequence, nobody took the piss. In fact, given the number of Mitre 5 footballs Harry had brought home during the last few years, Bobby had to concede that the arrangement had some advantages. Today was just about to be one of those occasions where the same held true.

‘Well, if you are serious about it, there’s a note on the staffroom noticeboard,’ said Harry, following a long period of making his ‘little stick of heaven’ vanish into perfectly constructed smoke rings.

‘Sayin’ what?’ A suddenly attentive Bobby turned for the first time to look directly at Harry.

‘A wee lassie’s lookin’ for a mobile disco for an eighteenth birthday party.’

‘Where?’ asked Bobby.

‘Ah telt ye! It’s on the noticeboard in the teach—’

‘Naw, naw … where’s the party?’ Initial exasperation diminished as Bobby realised his dad was gently pulling his leg.

‘The Sandriane. In about three weeks’ time. Her name’s Lizzie. She’s no at the school so ye might need tae be quick. She’s probably stuck the same note up oan other noticeboards tae. There’s a phone number at the bottom.’ There was another pause in the conversation as Harry could almost visualise the wee technicians in Bobby’s overheated brain working hard to compute the information he’d just been given. Harry laughed as Bobby’s eyes darted backwards and forwards. He pondered the idea of pressing Bobby’s nose to see if a piece of ticker paper would have come out of his mouth with the words ‘Get number please’ written on it.

‘Will ah get ye the number then?’ said Harry, jumping ahead.

‘Eh, em, aye. Ah think so …’ Bobby had moved onto rehearsing the conversation he would have with Joey later that afternoon. The Brain Trust techies had also started formulating some pertinent questions of their own: Where are you getting the equipment? Do you have enough records? What about lights? A van? A driver?

The wee bastards were asking too many questions now. They were supposed to be coming up with the fucking answers. That was their job. Bobby got up and headed for the stairs. He was shivering a fair bit, having just realised how long he’d been outside in the January air of a Scottish morning. He was planning to go and run a hot bath then get ready to go and get Joey. Probably contact Hamish May as well. Although he did think it might be better to have something more concrete to tell them. He should call this Lizzie and get the details. Make sure the job was actually still available. There was a lot to be done, but he had to acknowledge feeling a lot more vibrant than he had half an hour ago. Even Lemmy’s mob had fucked off.

‘Hullo, Bobby, son.’ Mrs Flanagan’s voice was as deep as a Cumnock coal mine and twice as dangerous. ‘Ah see ye hud yersel a wee time last night, spray paintin’ yer name oan the side ae Viviani’s shop wa.’

Ethel turned to look at Bobby, her mouth partly open.

‘Oh, ah’m sorry. Huv ah said too much?’ Mrs Flanagan put her hand over her mouth theatrically.

Auld fucking cow, thought Bobby as he edged past his tut-tutting mother and headed for the comparative safety of the bathroom.

‘There was something else ah wanted tae talk to you about, Bobby. But ah can’t remember whit though.’ Bobby and his dad were often concerned about Ethel’s increasing forgetfulness, but, today, and with the blood not yet starting to steep through Gary’s white T-shirt, he was grateful for it.

When Bobby got to the top of the stairs, he could hear the Sunday morning sound of the Human League coming from the small transistor radio; a sure sign that his sister had taken up residence in the bathroom. He’d be going nowhere soon. Bobby stealthily moved back down the stairs past his glowering mum and auld bag Flanagan who – just to rub it in – said a second cheery ‘Oh hullo, Bobby, son.’

Rot in Hell, you piss-stained auld cunt, he thought. Bobby hunted for the telephone. They had recently bought a new ‘mobile’ handset, which was absolutely fucking brilliant. It didn’t have much of a range and, at the size of a brick, it was bigger than the Bakelite one it had replaced, but with the aerial fully extended, you didn’t have to sit out in the hall – or in the same room as everybody else – when phoning your pals.

He inclined his foot forward far enough to see the slightly faded number. After five rings, a voice hoarser than auld ‘smelly cunt’ responded.

‘Hullo? Hullo?’ The voice said this with such timing that it was all Bobby could do to avoid replying ‘We are the Billy Boys …’ He didn’t, and the sandpaper sound snapped back at him.

‘Hullo! Who the fuck is this?’

‘Em, ah’m Bobby Cassidy. Who’s this?’

‘You phoned me ya cunt!’

‘Aye, but ah think ah might’ve been given the wrong number.’

‘Ah’m Franny fuckin’ Duncan. Noo whit dae ye want. Ah’m in ma fuckin’ scratcher.’

Franny Duncan. Jesus Christ. What was he doing with Fat Franny Duncan’s number written on his foot? Bobby’s brainiacs were running about in a panic. Words like ‘gangster’, ‘dealer’, ‘doings’, ‘big’, ‘fat’ and ‘bastard’ all ricocheted around like the steel balls in a multi-play pinball game.

‘Ah’m thinking of becomin’ a DJ.’ Bobby stumbled over the words, all too aware that he’d already volunteered his name.

‘For fuck’s sake. Phone back later on, at about four. Ask fur Hobnail. He’ll sort ye oot.’ Click. The phone flatlined, with a constant droning sound.

Bobby stared at it for a few seconds. Hobnail? Was that a fuckingcode word? Along with all those words that sprang to mind when thinking of Fat Franny Duncan came another two: ‘mobile’ and ‘DJ’. It was a big risk, but at least Franny Duncan would know where to get equipment, and might even have some for hire. Bobby Cassidy had taken one wee step back from the edge.

2

MEN MAKE PLANS AND GOD SMILES

2ND FEBRUARY 1982: 2:26PM

Fat Franny Duncan loved the Godfather movies, but he did not belong to this new band of theorists who reckoned II was better than I. For Fat Franny, original was most certainly best, although, given the success of the films and the timelessness of the story, he was staggered that there hadn’t been a III, like there had been with Rocky. He also couldn’t comprehend why there had been no book spin-off, although, even if there had, he would certainly not be wasting his time reading it. He knew the dialogue from both films pretty much by heart, and used their most famous quotes as a design for life. Particularly the lines of Don Corleone, who Fat Franny felt certain he would resemble later in his life. He was, after all, fat. There was no denying this. Bulk for Brando’s most famous character helped afford him gravitas and – as a consequence – respect; a level of respect that Fat Franny felt was within his grasp. Michael was a skinny Tally bastard and, although he undoubtedly commanded reverence, it was driven by fear.

Fat Franny was intent on pursuing a line of legitimacy with his business that would bring him universal veneration. The burgeoning entertainment venture was the vehicle for this. It had started reasonably well. The mobile DJ-ing had begun slowly, but over the last year and a half had branched into more lucrative gigs such as weddings and anniversary parties. There was money to be made in functions, of that there was no doubt. As a consequence, Fat Franny had assembled a roster: a collection of acts for every eventuality. From kids’ parties, to coming-of-age celebrations right up to charity do’s – Fat Franny Duncan had it all covered. So, as he surveyed his talent – sat at the kitchen table for their twice-weekly meeting in his expansive ex-council house – why did he feel like he wanted to stab a butcher’s knife through each of their hands?

‘Franny.’ A sheepish Bert Bole broke the silence that had engulfed all present for the last fifteen minutes.

Everyone at the table eyed their black-clad leader nervously. He ran chubby fingers through the thinning, greying hair on the top of his head and then tugged at the black hairband that was holding the rest of it in a tight ponytail. Finally, he teased at the slim moustache with his forefinger and thumb. To Bert Bole, it looked like a ritual before a slaughter.

‘Franny! Boss …?’ Bert had raised the level of his voice – but only slightly – in an attempt to get a reaction from the fat man with the faraway look in his eyes at the end of the table. Fat Franny often thought of the Don at times like this – and there had been a few too many lately. Surrounded by his subordinates, he imagined what Corleone would have said to Bob Dale – Fat Franny’s Luca Brasi – if these morons had told him what they’d just announced at the meeting.

Bob Dale responded, barley audible.

‘He hearths ye. He just disthnae belief ye!’ Bob Dale didn’t speak often. A hair-lip and ill-fitting teeth gave his speech a very pronounced lisp, which had been ridiculed mercilessly at school. As a consequence, Bob had found it more productive to retaliate with his fists than with his broken voice. His stature grew, along with a reputation that he was not to be messed with. But by that time the lasting damage was done. The legacy of those early brutal days was a nickname – Hobnail, which was the sound he made when trying to tell people who he was.

‘Nae tips? At a fuckin’ Cumnock wedding?’ By contrast, Fat Franny’s vocals were loud and, for the assembled entourage, all too clear. ‘Ye must be fuckin’ jokin’! Even the bastard minister usually comes awa wi’ a fifty spot.’ Don Franny spread his arms wide, then placed them at the ten-to-two position, palms face-down on the table top, before continuing, ‘… and a go on at least two ae the bridesmaids!’

Bob Dale smirked at this but was careful not to let Fat Franny see it. Almost everyone else remained silent with gazes averted. Only Jill Boothby – one half of married DJ duo Cheezee Choonz – indicated a wish to contribute, but her raised hand would remain unrecognised by the Chair for the rest of the meeting.

‘It’s like this …’ Fat Franny’s deep growl seemed to come from way down in his gut, reverberating around the bare walls of the cold, twice-extended kitchen. Again there was another long pause as Fat Franny visualised Hobnail clipping Bert Bole and then dumping his weighted body off the pier at Irvine Harbour. He refocused.

‘Like it or no, you fuckin’ clowns are part ae a business. Ah’m funding aw yer fuckin’ gigs here. Ah’m providin’ the equipment. Ah provide aw the security tae stop ye gettin’ a kickin’ at shiteholes like the Auchinleck Bowling Club.’ Fat Franny looked around the table at them all, one at a time, in a clockwise direction. ‘You lot – an’ ah can’t believe ah’m fuckin’ sayin’ this – are the fuckin’ talent.’

The Cheezees were motionless. Bert Bole had his hands outstretched, as if appealing for permission to speak. Mr Sunshine, the former children’s entertainer, appeared to be asleep.

‘Hoi … Sunshine!’ Fat Franny threw a cream doughnut, hitting the older man on the side of his face and dislodging his Dr Crippen-style spectacles. ‘Fuckin’ wake up, ya auld prick! This is for your benefit as well.’

Hobnail could tell Fat Franny’s mood was worsening and thought better of indicating the dollop of cream that was still attached to Mr Sunshine’s bizarre ginger beard.

‘You lot are just no bringin’ in enough, an’ it better fuckin’ change, a’right?’ Fat Franny pointed to Hobnail. ‘He tells me yir aw holdin’ oot on the tips.’ The talent all turned as one to look at the standing Bob Dale, who calmly folded his arms, shut his eyes and nodded.

‘So here’s whit’s gauny happen. Each ae ye needs to come up wi’ a gig of yer ain in the next month or yer out an’ ah’m gauny get other acts in.’ Fat Franny stood up quickly, causing his chair to fall dramatically behind him. ‘Ah’m away for a shite. Huv a good think about whit ah’ve just said.’

‘For God’s sake, put yer haun’ doon, he’s away,’ said Bert to Jill, once both Fat Franny and Bob Dale were well out of earshot. Although not the oldest of the four, Bert was generally their mouthpiece on the odd occasion when they felt a collective need to raise an issue with the fat man. Bert had been involved with Fat Franny’s crew for nearly three years. Back when they were both in their late thirties, Bert’s wife, Doris, had developed a serious gambling addiction. It had started pretty casually. A few nights at the bingo with friends from the BMK had progressed to include daytime visits to William Hill’s after she lost her job at the carpet factory.

Bert had ended up working extended shifts as a janitor at the James Hamilton Academy. He was well regarded by teachers and pupils alike, mainly due to an unshakeably optimistic outlook. He had a belief in human nature, which led him to attempt to do things for others even if it involved disadvantaging himself. His good nature helped Harry Cassidy to get a job as a fellow janitor, when a more selfish man – and especially one in his financial situation – might have been tempted to keep the additional shifts for himself. In the early part of 1979, things had started to become markedly worse for Bert and Doris Bole. Even though they both knew Doris had a significant problem, it wasn’t easy for them to talk about, and they dealt with it by effectively ignoring it. When they got into serious arrears with the rent and their growing utility bills, Bert took some well-intended advice and went to see Fat Franny Duncan over in Onthank. Nearly three years later, Bert was still working as a pub singer under an alias – Tony Palomino – paying off what had originally been a manageable £150 loan to clear a three-month rent backlog. A month after Bert had made this arrangement, Doris was dead.

A favour called in by Bert’s doctor to a fellow Mason in the Fiscal’s department ensured a verdict of ‘death by misadventure’. It was a convenient way of avoiding a verdict of suicide, by claiming that the overdose of anti-depressants that had actually killed her was accidental. It didn’t ultimately make a great deal of financial difference to Bert, but it did at least secure the pitiful insurance policy payout to cater for a decent cremation. His mates at the Hurlford Masonic Club paid for the wake. Fat Franny’s weekly compound interest calculations made sure the closure of the debt was always out of reach, so while Bert was somewhat imprisoned by history, he never quite understood the motivation of the others.

Mr Sunshine was a fifty-two-year-old bachelor, whose real name was Angus Archibald. He used to be a children’s entertainer, performing magic tricks and doing puppet shows. Despite a few criminal investigations relating to ‘improper activities’ in his past, he now worked under Fat Franny’s banner as a DJ for children’s parties. Two of Fat Franny’s minders – Des Brick and Wullie the Painter – constantly persecuted Mr Sunshine, calling him a ‘kiddy-fiddlin’ paedo’, amongst many other lurid things. The erstwhile Angus Archibald rarely got flustered by this, simply drawing on his pipe, tapping his nose and saying quietly, ‘Not proven.’ Mr Sunshine’s bizarre appearance also caused many a second look from parents who’d hired him. He was a heavy, but small man, and he didn’t carry the weight well. He looked a bit like the television magician, the Great Soprendo, but with a wispy ginger, partly combed-over hairpiece, pallid freckled face and trademark Wishee-Washee-style beard. It was a resemblance Mr Sunshine traded on, appropriating the ‘Piff, Paff, Poof’ catchphrase for his own performances. Given his ‘look’ and a suspect past, perhaps operating under Fat Franny’s wing was the only place he could get hired.

Cheezee Choonz were far harder to fathom. They were a married couple in their early thirties who only worked at weddings. Jay Boothby was reasonably talented. Unlike Bert Bole, he could actually sing, although, strangely, the Cheezees worked for Fat Franny as mobile DJs. Bert couldn’t really understand why, when there was an opportunity to earn more money by having a DJ-plus-singer offer for weddings, he was sent along with the Cheezees. Bert began to wonder if Fat Franny even knew Jay was a decent singer. He only became aware of it himself when he heard Jay testing out the microphones in an empty hall, a few months ago.

Jay was from Cumbria and Jill was from Cumnock. They ‘met’ through CB radio in the summer of 1980 and married six months later, moving to Kilmarnock in the hope of pursuing Jay’s dreams of becoming a club entertainer. Jill could take it or leave it frankly, but she had no real circle of friends and, as Fat Franny’s most prolific earners, being out with Jay almost every weekend left her with little time to spend with anyone else. Bert was equally uncertain how they had come to be part of Fat Franny’s Union, but, if he was honest, he had never really bothered to find out.

‘Have any of you three got any leads here?’ asked Bert.

‘Yer jokin’, aren’t ya?’ replied Jay Boothby. ‘Where are we gonna find the time to look for gigs? I hardly know anyone up here.’

‘Whit about you, Sunshine?’ Bert wasn’t hopeful, but felt that he should be inclusive.

‘Oh aye … the Cub Scouts have lined up a jamboree and the Crosshouse Mothers ‘n’ Toddlers Group have called for a bookin’ … and … and … whit the fuck dae you think? If ah could get gigs of ma own, d’you think I’d be here in this fat cunt’s freezin’ hoose?’