Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Birlinn

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

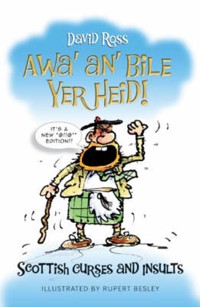

David Ross has produced an extraordinary, eclectic and hilarious collection of thematically arranged Scottish insults, abuse and invective which has been wonderfully illustrated throughout by Rupert Besley. The best insults, according to the author, occupy an indefinite space between wit and abuse, containing elements of both to varying degree; they must always sting the victim, or else they are a failure. This book is full of rich and expressive examples of insult and invective for all occasions from all over Scotland. These have been passed down through the centuries or have emerged in modern times, proving that clever insults are infinitely more amusing and memorable than good jokes. And so, happy reading. If you don't like it, awa' an' bile yer heid!

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 227

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Awa’ an’ Bile yer Heid!

David Ross is a professional writer with a number of serious historical books to his credit. As a long-time observer of his fellow-Scots he has also written Xenophobe’s Guide to the Scots and has compiled several anthologies of Scottish wit and humour. Among his current projects is one to have flyting restored as a national art form.

Rupert Besley has worked for 25 years as a freelance cartoonist illustrating books and drawing postcards of people not enjoying their holidays. His work has appeared in a variety of publications, including Punch, The Oldie and Country Life. He has written and illustrated a number of books of his own, including the bestselling The Cannae Sutra: The Scots Joy of Sex.

This edition first published in 2007 by Birlinn Limited West Newington House 10 Newington Road Edinburgh EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

Reprinted 2011, 2014

First published in 1999 by Birlinn Limited

Copyright © David Ross 1999, 2007 Artwork copyright © Rupert Besley 2007

The moral right of David Ross to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

ISBN 978 1 84158 594 9

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Typeset by Iolaire Typesetting, Newtonmore Printed and bound in Italy by Grafica Veneta

www.graficaveneta.com

Contents

Introduction

Architecture and buildings

Art and artists

Authors, critics and publishers

Beasts and birds

Curses and imprecations

Doctors and medicine

England and the English

Entertainment and the media

Epitaphs

Family life

Fashion and clothing

Fictional insults

Flyting

Food, drink and hospitality

Insulting terms

The Kirk, God and the Devil

Lairds, lords and toffs

The land and the people

The languages

Law and lawmen

Men

One-off demolition jobs

Parliament, politics and government

Personal remarks and put-downs

Personalities

Places

Repartee

Schools, universities and scholars

Scotland, as seen by others

Scots, as seen by others

Sports

Traditions and festivities

Travel and transport

Warfare

Women

Index of insulters and insultees

Introduction

There is something peculiarly satisfying about an effective and well-delivered insult – when it is applied to someone else, of course. The greatest satisfaction is to have created it, but to witness a good insult, or even to read it on the page, gives a certain kind of pleasure. It is a complex feeling, and when looked at closely, parts of it are not very nice, close to what Thomas Carlyle called ‘mischief-joy’, the pleasure in other people’s troubles. But there can also be a feeling of relief – somebody else is being being got at; and sense of justice done – someone is getting a well-deserved come-uppance. A clever insult also gets admiration for wit and boldness. Like microbes that survive in a wide range of environments, insults can live anywhere on the line between extreme malevolence and a sort of half-contemptuous fondness. One of their justifications has always been that ‘Sticks and stones will break your bones, but names will never harm you’, but unfortunately this is not always true, and sometimes name-calling is the cause of physical violence. But this collection deals with the insult only as a long-established form of self-expression – almost a minor artform. It has absolutely no hostile intentions against any person, place or point of view.

If an international insult ratings table existed, one feels that Scotland would stand high – here at least is a game in which the country punches above its weight. For this, in part, the neighbouring nation must be thanked. England has provided ample opportunity to sharpen Scottish barbs over the past thousand years.

But the sincerest insults are always nearest to home; and the Scots have always been enthusiastic insulters of one another. Why should this be? Without probing too far into the murk of the national psyche, one might note a certain competitiveness, a capacity for abstract thought, a sense of community which could often be stifling. Genetic, cultural, even climatic factors all come into it, no doubt. When David Hume described his fellow countrymen as ‘. . . the rudest, perhaps, of all the European nations, the most necessitous, the most turbulent, and the most unsettled’ (in a letter to Edward Gibbon of March 1776), he meant rude in the sense of rough, but it could equally have applied to their talk. A degree of refinement has crept in over the two hundred years plus since he wrote these words, and the Scots are no longer the most poverty-stricken Europeans; but, other things being equal, the great philosopher’s words keep a certain truth.

Through the centuries, the Scots have found a great deal to be rude about, but in addition the collection covers insults to Scotland and the Scots (we were surprised, even sometimes indignant, to find not everyone liked us). Conveniently arranged under broad subject headings, in its own way it offers a modest insight into the national character. And so, happy reading, or browsing. If you don’t like it – ‘Awa’ an’ bile yer heid!’

Architecture and buildings

The Armadillo.

A local name for the entrance hall of the Auditorium at the Scottish Exhibition & Conference Centre, Glasgow.

During a tour of New York, A.J. Balfour was shown over one of the city’s tallest and most recent skyscrapers. He was told how much it had cost to build, how many men had been employed in its construction, how long it had taken to build, and how fast the lifts travelled.

‘Dear me, how remarkable,’ he murmured. Finally his guide informed him that the building was so solid that it would easily last for a thousand years.

‘Dear, dear me, what a great pity.’

Noted of ARTHUR JAMES BALFOUR (1848–1930), in K. Williams, Acid Drops (1980)

I am sorry to report the Scott Monument a failure. It is like the spire of a Gothic church taken off and stuck in the ground.

CHARLES DICKENS (1812–70)

From my window I see the rectangular blocks of man’s

Insolent mechanical ignorance rise, with hideous exactitude, against the sun

against the sky.

It is the University.

ALAN JACKSON (1938– ), ‘From My Window’

. . . the ceilings are so low all you can have for tea is kippers.

CHARLES MCKEAN, The Scottish Thirties, 1987, on bungalows

. . . a very strange house . . . that it should ever have been lived in is the most astonishing, staggering, saddening thing of all. It is surely the strangest and saddest monument that Scott’s genius created.

EDWIN MUIR (1887–1959), Scottish Journey, on Abbotsford

The rocks of the castle . . . guide the eye to barracks at the top and cauliflowers at the bottom.

JOHN RUSKIN (1819-1900), The Poetry of Architecture, on Edinburgh Castle

The wise people of Edinburgh built . . . a small vulgar Gothic steeple on the ground and called it the Scott Monument.

JOHN RUSKIN (1819-1900), The Poetry of Architecture

Standing on the ramparts of Stirling Castle, the spectator cannot help noticing an unsightly excrescence of stone and lime rising on the brow of the Abbey Craig. This is the Wallace Tower.

ALEXANDER SMITH (1830–67), A Summer in Skye

Day by day, one new villa, one new object of offence, is added to another; all around Newington and Morningside, the dismallest structures keep springing up like mushrooms; the pleasant hills are loaded with them, each impudently squatted in its garden . . . They belong to no style of art, only to a form of business.

ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON (1850–94),Picturesque Notes on Edinburgh

At last I view the storied scene,

The embattled rock and valley green;

And hear, mid reverent nature’s hush,

The water closet’s frequent flush.

JOHN WARRACK, letter to The Scotsman protesting against the building of a public lavatory in Princes Street Gardens, Edinburgh (December 1920)

Why do you propose these boxes for our people?

JOHN WHEATLEY (1873–1930), on official standards for house-building, 1923

It is worse than ridiculous to see the people of Dumfries coming forward with their pompous mausoleum.

WILLIAM WORDSWORTH (1770–1850), Letter to John Scott (1816), on the Burns tomb in Dumfries

Those sunless courts, entered by needles’ eyes of apertures, congested with hellish, heaven-scaling barracks, reeking with refuse and evil odours, inhabited promiscuously by poverty and prostitution.

ISRAEL ZANGWILL (1864–1926), on Edinburgh tenements (1895)

Art and artists

May the Devil fly away with the fine arts!

THOMAS CARLYLE (1795–1881), Latter-Day Pamphlets

. . . many of these artists in this exhibition seem to have an overt and blatant concern with money and, inevitably, status. They have dramatically reduced the scope and vision of their art so that it may become a saleable commodity, a potential piece of private property and a casual investment for Scotland’s doomed and essentially philistine bourgeoisie.

KEN CURRIE, reviewing the exhibition ‘Contemporary Art from Scotland’ in Stigma 2 (1983)

Arts Councils are the insane asylums of bureaucracy.

IAN HAMILTON FINLAY (1925–2006), ‘An Alphabet’, Studio International (1981)

. . . the unfortunate monarch, whose head was executed as ruthlessly on canvas as she herself had been at Fotheringay

H. GREY GRAHAM, The Social Life of Scotland in the Eighteenth Century (1899), on posthumous portraits of Mary, Queen of Scots (1542–87)

‘My dear Roberts,’ wrote the critic in a private letter, ‘you may have seen my remarks on your pictures. I hope they will make no difference to our friendship. Yours, etc.’ ‘My dear —,’ wrote the painter in reply, ‘the next time I meet you I shall pull your nose. I hope it will make no difference to our friendship. Yours, etc., D. Roberts.’

TOLD OF DAVID ROBERTS (1796–1864), in Alexander Hislop,The Book of Scottish Anecdote

. . . the word ‘art’ in Scotland . . . a condensed expression for ‘l’art de se faire ridicule’

JOHN RUSKIN (1819–1900), The Poetry of Architecture

Authors, critics and publishers

It is really very generous of Mr Thomson to consent to live at all.

Anonymous contemporary critic of James Thomson (1834–1882), poet of voluptuous death, quoted in notes to Douglas Young,Scottish Verse 1851–1951

Why bother yourself about the cataract of drivel for which Conan Doyle was responsible?

JOSEPH BELL (1837–1911), said to have been Conan Doyle’s model for Sherlock Holmes, in a letter

The archetypal Scottish sexist.

ALAN BOLD (1943–98), The Sensual Scot, on Robert Burns

One good critic could demolish all this dreck, but one good critic is precisely what we do not have. Instead we are lumbered with pin-money pundits, walled-up academics or old ladies of both sexes.

EDDIE BOYD (1916–1989), on Scottish drama and drama critics, in Cencrastus (Autumn 1987)

‘It adds a new terror to death.’

LORD BROUGHAM (1778–1868), Lord Chancellor of Great Britain, on Lord Campbell’s Lives of the Lord Chancellors (1845–47)

O thou whom poesy abhors,

Whom prose has turned out of doors!

Heardst thou that groan?

Proceed no farther:

’Twas laurelled Martial roaring murther.

ROBERT BURNS (1759–1796), on James Elphinston’s (1721–1809) translation of Martial’s Epigrams

And think’st thou, Scott! by vain conceit perchance,

On public taste to foist thy stale romance . . .

No! when the sons of song descend to trade,

Their bays are sear, their former laurels fade.

Let such forgo the poet’s sacred name,

Who rack their brains for lucre, not for fame.

LORD BYRON (1788–1824), English Bards and Scotch Reviewers, on Sir Walter Scott

My northern friends have accused me, with justice, of personality towards their great literary anthropophagus, Jeffrey; but what else was to be done with him and his dirty pack, who feed by ‘lying and slandering’ and slake their thirst with ‘evil speaking?’

LORD BYRON, postscript to the second edition of English Bards and Scotch Reviewers, on Francis Jeffrey and the Edinburgh Review

Napoleon is a tyrant, a monster, the sworn foe of our nation. But gentlemen – he once shot a publisher.

THOMAS CAMPBELL (1777–1844), proposing a toast to Napoleon Bonaparte at a writers’ dinner

Fricassee of dead dog . . . A truly unwise little book. The kind of man that Keats was gets ever more horrible to me. Force of hunger for pleasure of every kind, and want of all other force – such a soul, it would once have been very evident, was a chosen ‘vessel of Hell’.

THOMAS CARLYLE (1795–1881), on Monckton Milnes’s Life of Keats

A weak, diffusive, weltering, ineffectual man . . . Never did I see such apparatus got ready for thinking, and so little thought. He mounts scaffolding, pulleys and tackle, gathers all the tools in the neighbourhood with labour, with noise, demonstration, precept, abuse, and sets – three bricks.

THOMAS CARLYLE (1795–1881), on Samuel Taylor Coleridge

A more pitiful, rickety, gasping, staggering, stammering Tomfool I do not know. Poor Lamb! Poor England! when such a despicable abortion is given the name of genius.

THOMAS CARLYLE (1795–1881), on Charles Lamb

Shelley is a poor creature, who has said or done nothing worth a serious man being at the trouble of remembering.

THOMAS CARLYLE (1795–1881), on Percy Bysshe Shelley

At bottom, this Macaulay is but a poor creature with his dictionary literature and erudition, his saloon arrogance. He has no vision in him. He will neither see nor do any great thing.

THOMAS CARLYLE (1795–1881), on Lord Macaulay

. . . standing in a cess-pool, and adding to it

THOMAS CARLYLE (1795–1881), quoted in Jean Overton Fuller,Swinburne (1968), on Algernon Charles Swinburne

All his life he loved attempting magnificent things in a slapdash way and, whatever others might think, he was seldom dissatisfied with the result.

DONALD CARSWELL (1882–1940) on J.S. Blackie, in Brother Scots (1927)

Joanna Baillie is now almost totally forgotten, even among feminist academics dredging the catalogues for third-rate women novelists . . . Her life story is a quaint one, interesting for being so dull.

RUPERT CHRISTIANSEN, Romantic Affinities (1988), on the C19th tragedian Joanna Baillie

. . . to conclude, they say in few words

That Gilbert is not worth two cow turds,

Because when he has crack’t so crouse,

His mountains just bring forth a mouse.

SAMUEL COLVILLE or COLVIN, Pindarique Ode on Bishop Burnet’s ‘Dialogues’, c. 1689; Gilbert Burnet (1643–1715) became Bishop of Salisbury under William of Orange and was detested by both Presbyterians and Jacobites

The man’s mind was not clean . . . he degraded and prostituted his intellect, and earned thereby the love and worship of a people whose distinguishing trait is fundamental lewdness . . . Put into decent English many of his most vaunted lays amount to nothing at all . . . His life as a whole would have discredited a dustman, much less a poet . . . a superincontinent yokel with a gift for metricism.

T.W.H. CROSLAND, The Unspeakable Scot (1902), on Robert Burns (and his fellow countrymen)

. . . deplorable is the mildest epithet one can justly apply to it. Wordsworth writes somewhere of a person ‘who would peep and botanise about his mother’s grave’. This is exactly the feeling that a reading of Margaret Ogilvy gives you.

T.W.H. CROSLAND, The Unspeakable Scot, on Sir J.M. Barrie’s memoir of his mother

It is with publishers as with wives: one always wants someone else’s.

NORMAN DOUGLAS (1868–1952)

Mr Coleridge was in bad health; – the particular reason is not given; but the careful reader will form his own conclusions . . . Upon the whole, we look upon this publication as one of the most notable pieces of impertinence of which the press has lately been guilty.

The Edinburgh Review, anonymous review of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s Kubla Khan (1816)

On Waterloo’s ensanguined plain

Lie tens of thousands of the slain;

But none, by sabre or by shot,

Fell half so flat as Walter Scott.

THOMAS, LORD ERSKINE (1750–1823), on Sir Walter Scott’s ‘The Field of Waterloo’

It is a story of crofter life near Stonehaven; but it is questionable if the author, or authoress, is correct in the description of crofter girls’ underclothing of that period.

Fife Herald book review of Lewis Grassic Gibbon’sCloud Howe, quoted in L. Grassic Gibbon and Hugh MacDiarmid, Scottish Scene (1934)

The bleatings of a sheep.

JOHN FRASER, Professor of Celtic at Oxford University, on the translations from Gaelic of Kenneth Macleod (1871–1955), quoted in The Memoirs of Lord Bannerman of Kildonan

Mr Gunn is a brilliant novelist from Scotshire who chooses his home county as the scene of his tales . . . he is the greatest loss to itself that Scottish literature has suffered in this century.

LEWIS GRASSIC GIBBON (James Leslie Mitchell, 1901–35),Scottish Scene

Welsh’s market remains captive: the inarticulate 20-somethings, call-centre folk, cyberserfs, unsmug unmarrieds who infest [city centre] fun palaces. Welsh is to this lot what, in his happier days, Jeffrey Archer was to Mondeo Man: the jammy bastard who did well.

CHRISTOPHER HARVIE (1944– ) quoted by Senay Boztas,Sunday Herald, 23 January 2005, on Irvine Welsh

wee Maurice (most minuscule of makars)

HAMISH HENDERSON (1920–2002), letter to Hugh MacDiarmid, 3 April 1949, on Maurice Lindsay

The final word on Burns must always be that he is the least rewarding of his country’s major exports, neither so nourishing as porridge, or stimulating as whisky, nor so relaxing as golf.

KENNETH HOPKINS, English Poetry, quoted in Hugh MacDiarmid, Lucky Poet (1943)

If you imagine a Scotch commercial traveller in a Scotch commercial hotel leaning on the bar and calling the barmaid Dearie, then you will know the keynote of Burns’s verse.

A.E. HOUSMAN (1859–1936), quoted in Jonathon Green,Dictionary of Insulting Quotations (1996)

Dr Donne’s verses are like the Peace of God, for they pass all understanding.

KING JAMES VI (1566–1625), attributed, on the poems of John Donne

This will never do!

LORD JEFFREY (1773–1850), reviewing Wordsworth’s ‘The Excursion’ in The Edinburgh Review, November 1814

Writers are too difficult.

A member of the Glasgow Festivals Unit team, on why so few writers were involved in the city’s ‘Culture Year’ (1990), quoted in James Kelman, Some Recent Attacks (1992)

Yuh wrote? A po-it? Micht ye no’ juist as weel hae peed inti thuh wund?

MAURICE LINDSAY (1918– ) recalling the comment of an anonymous Glaswegian ‘In a Glasgow Loo’, from Robin Bell, The Best of Scottish Poetry (1989)

Does she, poor silly thing, pretend

The manners of our age to mend?

Mad as we are, we’re wise enough

Still to despise sic paultry stuff.

JANET LITTLE (1759–1813), ‘Given to a Lady Who Asked Me To Write a Poem’

. . . calm, settled, imperturbable drivelling idiocy . . . We will venture to make one small prophecy, that his bookseller will not a second time venture £50 on any thing he can write. It is a better and a wiser thing to be a starved apothecary than a starved poet; so back to the shop, Mr John, back to ‘plasters, pills, and ointment boxes, etc’.

J.G. LOCKHART (1794–1854), in Blackwood’s Magazine, 1818, on John Keats’s ‘Endymion’

Servile and impertinent, shallow and pedantic, a bigot and a sot, bloated with family pride, and eternally blustering about the dignity of a born gentleman, yet stooping to be a talebearer, and eavesdropper, a common butt in the taverns of London . . . Everything which another man would have hidden, everything the publication of which would have made another man hang himself, was matter of exaltation to his weak and diseased mind.

LORD MACAULAY (1800–59), on James Boswell (1740–95)

. . . high-falutin’ nonsense,

Spiritual masturbation of the worst sort.

HUGH MACDIARMID (C.M. Grieve, 1892–1978), on the ‘Celtic Twilight’ works of Fiona Macleod (William Sharp, 1856–1905)

I remember well when Mr Lindsay first climbed on to the bandwagon of the Scottish Renaissance Movement. He came to see me about it. I had no difficulty whatever in appreciating that under his natty khaki shirt what may be described as his bosom was warming with the glowing ecstasy of a dog sighting a new and hitherto undreamed-of lamp-post.

HUGH MACDIARMID (C.M. Grieve, 1892–1978), ‘A Soldier’s Farewell to Maurice Lindsay’, in National Weekly (June 1952); Lindsay had criticised MacDiarmid’s introduction to a Scottish concert at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London

Calf-fighter Campbell . . .

there’s an operation to do first

– To remove the haemorrhoids you call your poems

HUGH MACDIARMID (C.M. Grieve, 1892–1978), on Roy Campbell, the Spanish-dwelling Scoto-South African poet

Campbell, they call him – ‘crooked mouth’ that is –

But even Clan Campbell’s records show no previous case

Of such extreme distortion, of a mouth like this

Slewed round to a man’s bottom from his face

And speaking with a voice not only banal

But absolutely anal

HUGH MACDIARMID (C.M. Grieve, 1892–1978), still on Roy Campbell

There was another old lady who knew and loved the songs of the bard William Ross. This particular morning she spent singing William Ross’s songs behind closed doors. A pious neighbour overheard her beautiful singing . . . She came in later and said, ‘Yours was the beautiful singing this morning. Surely it was the Psalms of David that you sang.’

‘David, the excremental blackguard!’ replied the other.

‘What good was he compared to William Ross?’

CALUM MACLEAN, The Highlands of Scotland (1975)

He is writing a novel and his characters all want soaking in double strong disinfectant for a week.

RHEA MITCHELL, wife of Lewis Grassic Gibbon, in a letter of March 1927 about his first novel, Stained Radiance

Men of sorrow, and acquainted with Grieve.

EDWIN MUIR (1887–1959), on the Scottish writers of his time

Next to tartan and soldiers, poetry is the greatest curse of contemporary Scotland. It is the intellectuals’ special form of dope, which they can indulge in with a good conscience while the crowds go mad up on the Castle esplanade.

TOM NAIRN (1932– ), ‘Festival of the Dead’, in New Statesman, September 1967

For thee, James Boswell, may the hand of Fate

Arrest thy goose-quill and confine thy prate!

. . . To live in solitude, oh! be thy luck,

A chattering magpie on the Isle of Muck.

PETER PINDAR (John Wolcot, 1738–1819), Bozzy and Piozzi

Ne’er

Was flattery lost on poet’s ear;

A simple race! they waste their toil

For the vain tribute of a smile.

SIR WALTER SCOTT (1771–1832), The Lay of the Last Minstrel

Alexander MacDonald schoolmaster of Ardnamurchan is an offence to all sober well-inclin’d persons as he wanders thro’ the country composing Gaelic songs, stuffed with obscene language.

Society for the Propagation of Christian Knowledge, Minutes for June 1745, referring to Alexander MacDonald (the poet Alasdair MacMaighstir Maighstir)

She has dedicated her menopause to me.

MURIEL SPARK (1918–2006) on an American editor who criticised her autobiography, Curriculum Vitae

Poor Henry is on the point of death, and his friends declare that I have killed him. I received the information as a compliment, and begged they would not do me so much honour.

GILBERT STUART (fl. C18th), who conducted a literary vendetta against the historian Dr Henry, in a letter, 3 April 1775

As artists we situate ourselves at the level of man-at-crap.

ALEXANDER TROCCHI (1925–84), quoted in Andrew Murray Scott,Alexander Trocchi: The Making of the Monster (1991)

It is not poetry. Here, most frequently, we have neither rhyme nor reason. We have the utterance of much that should never find expression in decent society . . . It sounds like Homer after he had swallowed his false teeth.

LAUCHLAN MACLEAN WATT, reviewing Hugh MacDiarmid’s poem ‘To Circumjack Cencrastus’ (in which there is a mocking reference to himself)

Even without a book to promote, Fry would, in the interests of self-publicity, cheerfully announce his conversion to the flatness of the earth or testify to his encounters in an Edinburgh hostelry with little men from outer space.

BRIAN WILSON, Scotland on Sunday, 8 October 2006, on the historian Michael Fry

As a poet Scott cannot live . . . What he writes in the way of natural description is merely rhyming nonsense.

WILLIAM WORDSWORTH (1770–1850), in a conversation reported by Mrs Davy, 1844, on Sir Walter Scott

Beasts and birds

She had the fiercie and the fleuk,

The scheerloch and the wanton yeuk;

On ilka knee she had a breuk –

What ail’d the beast to dee?

PATRICK BIRNIE (fl. 1660), ‘The Auld Man’s Mear’s Dead’

I turned a grey stone over: a hundred forkytails seethed from under it like thoughts out of an evil mind.

GEORGE MACKAY BROWN (1921–96), ‘Five Green Waves’

Ye ugly, creepin, blasted wonner,

Detested, shunn’d by saint and sinner,

How daur ye set your fit upon her –

Sae fine a lady?

Gae somewhere else, and seek your dinner

On some poor body.

ROBERT BURNS (1759–96), ‘To a Louse’

A puddock sat by the lochan’s brim,

An’ he thocht there was never a puddock like him . . .

A heron was hungry, and needin’ tae sup,

Sae he nabbit the puddock and gollupt him up;

Syne runkled his feathers: ‘A peer thing,’ quo’ he,

But – puddocks is nae fat they eesed tae be.’

J.M. CAIE (1878–1949), ‘The Puddock’

The confounded fleas of mischief and grief . . .

If I could round you all up and stow you in a barrel

And were I blessed with the means I’d send you to Adolf,

Mixed with body-hugging crablice and bugs from the rugs

I’d have it poured about his skull and he’d be locked in his room.

ANGUS CAMPBELL (1903–82), ‘The Fleas of Poland’, from the Gaelic

I kicked an Edinbro dug-lover’s dug.

Leastways, I tried; my timing was ower late,

It stopped whit it was daein on my gate

An skelpit aff to find some ither mug.

ROBERT GARIOCH (Robert Garioch Sutherland, 1909–81), ‘Nemo Canem Impune Lacessit’

Of all forms of life, surely the most vile. The cleg was silent, the colour of old horse manure, a sort of living ghost of evil.

NEIL M. GUNN (1891–1973), Highland River, on the cleg

Snails too lazy to build a shed.

GEORGE MACDONALD (1824–1905), Little Boy Blue, on slugs