11,88 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Amber Books Ltd

- Sprache: Englisch

On 14 April 1912, less than a week into a transatlantic trip from Southampton to New York, the largest luxury cruise liner in the world struck an iceberg off the coast of Labrador, causing the hull to buckle. The massive 50,000 ton ship hailed as ‘unsinkable’ was soon slipping into the cold Atlantic Ocean, the crew and passengers scrambling to launch lifeboats before being sucked into the deep. Of the 2,224 passengers and crew aboard, more than 1,500 died, making the sinking one of the deadliest for a single ship up to that time. The sinking has captured the public imagination ever since, in part because of the scale of the tragedy, but also because the ship represented in microcosm Edwardian society, with the super-rich sharing the vessel with poor migrants seeking a new life in North America. Other factors, such as why there were only enough lifeboats to hold half the passengers, also caused controversy and led to changes in maritime safety. In later years many survivors told their stories to the press, and Titanic celebrates these accounts. A final chapter examines the shipwreck today, which has been visited underwater by explorers, scientists and film-makers, and many artifacts recovered as the old liner steadily disintegrates. Titanic offers a compact, insightful photographic history of the sinking and its aftermath in 180 authentic photographs.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 127

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

14 April 1912:

TITANIC

14 April 1912:

TITANIC

David Ross

This digital edition first published in 2023

Copyright © 2023 Amber Books Ltd

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior written permission of the copyright holder.

Published by Amber Books Ltd

United House

London N7 9DP

United Kingdom

www.amberbooks.co.uk

Facebook: amberbooks

Instagram: amberbooksltd

Twitter: @amberbooks

Pinterest: amberbooksltd

ISBN: 978-1-83886-420-0

Editor: Michael Spilling

Designer: Keren Harragan

Picture research: Terry Forshaw

Contents

INTRODUCTION

BACKGROUND TO A TRAGEDY

THREE GIANT SISTERS

THE VOYAGE

THE COLLISION

THE LIFEBOATS

AFTERMATH

PICTURE CREDITS

Introduction

DEPARTURE

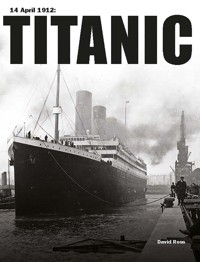

Titanic sets off from Southampton for New York, on 10 April 1912.

The wreck of the Royal Mail Steamer Titanic, making its maiden voyage on 14 April 1912, is one of the events that gave the twentieth century its specific character. The enduring appeal of the Titanic’s fate is that it should never have happened, and the reasons, and their ramifications, can be endlessly explored. Also, it was a wholly civilian disaster: ships would be sunk with even greater loss of life in the decades that followed, but mostly in the course of warfare.

The story begins in pride and confidence, with the ambition and technical skills to build three ‘practically unsinkable’ super-liners, more than half as big again as their rivals, which would also be the last word in comfort and luxury. It very soon turns into disaster, when the ship scrapes against an iceberg and sinks in less than three hours. There are only enough lifeboats for half those on board.

With Titanic gone, a dreadful scene ensues as almost 1500 people perish on the wreck or in the water. Finally, there is gallantry and relief as the RMS Carpathia braves the icefield to come at full speed to rescue the survivors.

And then, the memories, the inquiries, the ‘whitewash’ – and, 73 years later, the discovery and exploration of the wreck. With books, films, stage musicals, and museums in several countries, the Titanic forms the basis, twenty-first century style, of a large cultural, educational and, not least, commercial international enterprise that continues to fascinate to this day.

INVITATION TO THE VOYAGE

White Star Line posters were designed to attract passengers with the impressiveness, stability and sheer size of Olympic and Titanic.

HOME OF MEMORIES

The striking Titanic museum building in Belfast, opened in 2012 on the site where the liner was built.

BACKGROUND TO A TRAGEDY

Up until the late 1850s, few people crossed the Atlantic Ocean unless driven by necessity or force. From the European and British explorers of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, to the venturesome colonists of the seventeenth and eighteenth (and the infamous slave traffic that followed), human movement westward across the Atlantic grew steadily. By the 1840s, emigrants to the USA were being numbered in hundreds of thousands. Many of the migrants were desperately poor and, on most ships, had to provide or buy their own food.

The small ships of the early nineteenth century were slow, overcrowded, insanitary and disease-ridden. But for emigrants from European countries, the USA promised a new start in a democratic republic. It was the New World, rich in opportunity.

JOURNEY’S END

Immigrants get their first view of the Statue of Liberty as their ship reaches New York harbour, circa 1910. Many wept.

RISING DEMAND, IMPROVED COMFORT

Conditions for migrants improved from the 1850s with the advent of larger, faster ships, together with greater regulation of conditions on board. By the end of the century, though many migrants were still almost destitute, a degree of order had been introduced. Charities and friendly societies often helped with passage costs, and established immigrant communities could provide assistance on arrival.

Another factor also changed the situation. As wealth grew in the industrialized nations and communications improved (the Atlantic telegraph cable was laid in 1858), shipping lines began to cater for an increasing demand from wealthier travellers, who expected and paid for standards similar to those of good hotels. Migrants were the bread and butter of the shipping lines, but first- and second-class passengers provided highly desirable jam.

Iron screw-propelled ships were introduced in 1850 by the Inman Line. Faster, roomier and safer, they were soon imitated by Cunard and other companies.

LAND OF PROMISE

For many immigrants who had left hutted villages in the European or Irish countryside, the sight of the Manhattan skyline seemed almost unreal.

FRESH AIR

Steerage passengers on the well deck of the German liner Pretoria, built in 1898. At 11,975 tonnes (13,200 tons), the ship packed in 2600 passengers – more than Titanic.

A MUSICAL TRIBUTE

Cover of the music for a march composed in honour of the Inman Line’s founder (1825–81), who gave a free transatlantic passage to the band of the Grenadier Guards for the ‘World Peace Jubilee’ celebrated in Boston in 1872. City of Brussels sank in 1883 with the loss of 10 lives.

The White Star Line was a comparative latecomer to the Atlantic. Formed in 1845, its routes were to China and Australia. By 1867, it was part of the Liverpool, Melbourne & Oriental Steam Navigation Company, which went bankrupt that year. Its assets were acquired for £1000 by Thomas Henry Ismay (1837–99), a Liverpool-based shipbroker, who reformed it as the Oceanic Steam Navigation Company in 1869, but retained the White Star trading name.

FAMILY CONCERNS

In many ways, the Titanic story is bound in with close family ties. Cousins, brothers-in-law, sons and nephews collaborated in a relationship of reciprocal value between two large companies involved in separate aspects of the maritime industry. A wealthy Liverpool merchant, Gustav Christian Schwabe (1813–97), was the link. He had helped Ismay to acquire White Star’s assets and restore its fortunes, and was also a partner in the Bibby shipping line. According to the Dictionary of National Biography, it was he who encouraged Ismay to enter the Atlantic trade.

THOMAS HENRY ISMAY (1837–99)

Born in Maryport, Cumbria, to a ship-owning family, he acquired the bankrupt White Star Line in 1867 and built it up into a major shipping company on the Oriental and North Atlantic routes. He was also the first to provide proper family accommodation for steerage passengers.

EASTBOUND CROSSING

An American poster produced for the International Mercantile Marine Corporation in 1911. Like almost all publicity pictures for the White Star giants, it shows Olympic, though the name is obscured.

GUSTAV CHRISTIAN SCHWABE (1813–97)

Schwabe’s business acumen was such that he became one of the richest men in England. A keen chess player, he appears to have moved companies about with equal skill. It is likely that the varied shipping interests left on his death contributed to the formation of the International Mercantile Maritime Corporation.

Ismay needed little encouragement: the North Atlantic route was lucrative and growing, and he wanted not merely a share of the traffic, but to dominate it. However, as a prudent businessman, he realized his new company had to have something special to offer. Gustav Schwabe provided the answer. Mrs Schwabe had a young cousin, Edward Harland, born in Scarborough in 1831, who showed a flair for mechanics and engineering. With Schwabe as his patron, Harland got a thorough training in shipbuilding at Glasgow and Liverpool.

In 1854, he crossed to Belfast as manager of Hickson’s shipyard, a struggling enterprise. His tough, efficient management turned the business around and in 1858 he bought the yard from Hickson and renamed it Edward James Harland & Co. The year before, he had taken on Schwabe’s nephew, Gustav Wolff, as his assistant. Schwabe was convinced that Belfast, just across the Irish Sea from Liverpool, could prosper as a shipbuilding centre. The new company was set on its way with an order for three ships from the Bibby Line, followed by a further six in 1860. In 1861, Wolff was made a partner, and Harland & Wolff was established.

MANAGERS AND PARTNERS

This photograph, from the early 1890s, shows (left to right) Gustav Wolff, Walter H. Wilson (then managing director), William Pirrie and Edward Harland. By this time, executive management was very much with Wilson and Pirrie. Wolff said jokingly, ‘Sir Edward builds the ships, Mr Pirrie makes the speeches, and as for me, I smoke the cigars.’

Pirrie was born in Quebec, Canada, and brought up in Belfast. He joined Harland & Wolff in 1862, became a partner in 1874, and chairman after Edward Harland’s death. A prostate operation prevented him from joining Ismay and Andrews on the Titanic. Harland’s father was a doctor, and a friend of George Stephenson, the ‘father of railways’. Harland himself was apprenticed to Robert Stephenson’s engineering works at Newcastle.

LONG, NARROW IRON BOX

If old-fashioned nepotism had helped set it up, there was nothing old-fashioned about its approach. The typical Harland & Wolff ship was in effect a long, narrow iron box, compared by some to a giant box girder, and with a flat bottom. This of course was an excellent arrangement for the stowage of cargo. The Bibby ships, distinctive in appearance, were half-derisively known as ‘Bibby’s coffins’, but the design was a success and its successors still sail today as car-carriers and container ships.

Harland & Wolff was flourishing by 1869, and with Gustav Schwabe as a godfather to both, it is no surprise that the revived White Star Line should look to Belfast for its ships. From the beginning, there was a special relationship, with new ships being priced at an agreed construction cost plus an extra percentage (usually 4 per cent) so that both sides knew exactly what would be provided and what it would cost.

Ismay’s special offer was his ships. His first liner was Oceanic (1870) whose ‘ic’ suffix set the pattern for naming all successors. Powered by steam and sail, its gross tonnage was 3766 tonnes (3706 tons). Built to the standard Harland & Wolff box pattern, it carried 166 ‘saloon’ passengers and 1000 emigrants, housed mostly at the stern (the ‘steerage’).

Oceanic embodied Ismay’s ideas about what his passengers wanted. It was not especially fast (there was already competition for the Blue Riband usually held by Cunard), but it suffered from less mechanical vibration than its rivals, and the slightly longer voyage was made agreeable for the saloon passengers by more spacious accommodation and more amenities. The steerage area was also an improvement on previous practice, with family accommodation and proper catering.

White Star became a popular choice for passengers, and by 1874 Oceanic had six sister-ships. The company’s reputation survived the wreck of the Atlantic in fog off Nova Scotia in 1873, when some 580 people were drowned and blame fell on the captain and his officers for, among other omissions, having no lookout on the masthead and failing to reduce speed.

WHITE STAR SHIPS

The diagram gives key facts and relative proportions of White Star ships from Oceanic (1870) to Titanic. The tendency to build several ships of the same ‘class’ goes back to the start of commercial shipbuilding and was common in other large shipping lines.

A FRENCH RIVAL

The first-class dining room of La Gascogne, one of the liners of the Compagnie Générale Transatlantique, sailing between Le Havre and New York, after an 1894 refit. The scale of Titanic can be realized by the fact that its first-class dining room was more than twice as big.

ISMAY’S FIRST TRANSATLANTIC LINER

Oceanic was the first ship to be built by Harland & Wolff for White Star. Launched on 27 August 1870, it was a very up-to-date ship for its time, and the first of six sister-ships. The hull was divided into six watertight compartments, and the four sail-bearing masts were supplemented by a four-cylinder compound steam engine. This ship could carry 1000 steering and 166 saloon passengers. It was one of the first ships to provide running water in the saloon cabins. Oceanic was scrapped in 1896, to be succeeded by the much larger second Oceanic.

THE WRECK OF THE ATLANTIC

Atlantic was White Star’s worst disaster until the loss of the Titanic. On 1 April 1873, the Atlantic struck rocks off Marr’s Head, Nova Scotia. Despite the proximity to land, 563 out around 950 people on board perished. The company did not reuse the name.

AMERICAN INFLUENCE

In 1874, another dynamic figure became a partner in Harland & Wolff: William James Pirrie (1847–1924), who had joined in 1862 as a premium apprentice and only two years later was made chief draughtsman.

Edward Harland and Gustav Wolff largely withdrew from day-to-day business and, at only 27, Pirrie in effect took command of the company, a role he would hold until 1912 and beyond. In 1882, Joseph Bruce Ismay (1862–1937), Thomas’s eldest son, joined his father’s office and gained experience with visits to Australia and New Zealand, before managing White Star’s office in New York. He returned to England in 1891 as a partner in Ismay & Co. and became chairman of the White Star Line after his father’s death in 1899.

Bruce Ismay had high-level American contacts but it was Pirrie who took the leading role in bringing the White Star Line into an international consortium of shipping companies, the International Mercantile Marine Company (IMM), formed in 1902 with funds from the tycoon banker John Pierpont Morgan. Taking three-quarters of its sale price in preferred (first in line for dividend payments) shares, White Star was the dominant element in IMM and J. Bruce Ismay became its chairman in 1904.

A key aspect of the deal was the continuing close relationship between Harland & Wolff and White Star. The preferential cost-plus building rate was also extended to the other companies in the group, providing a steady flow of orders for the yard.

WHITE STAR OFFICES

The White Star office building in Cockspur Street, London, decorated for the coronation of King George V on 22 June 1911. A placard extolling the size of Olympic is above the main door.

THOMAS ANDREWS (1873–1912)

Andrews joined Harland & Wolff as a premium apprentice in 1889 and became managing director in charge of design. He was closely involved in the planning and completion of Olympic and Titanic, and led the builders’ ‘Guarantee Group’ on board the ship. He was first to assess the extent of flooding and to pronounce the sinking as inevitable. He was lost with the ship.

Belfast in the 1900s had become a large, flourishing industrial city, with the shipyard as its pre-eminent business, with some 15,000 employees and supporting a variety of other industries and businesses. The men who ran the shipyard became leading personalities in the city, involved in local politics, charities and urban development. William Pirrie was made a baron in 1906.

CUNARD vs WHITE STAR

Completion of the IMM deal created controversy. The British government, disliking the American ownership and monopolistic nature of IMM, lent large sums to the Cunard Line to construct two super-liners, which entered service in 1907: Mauretania and Lusitania. Bigger than anything else on the Atlantic, fast and luxurious, they proved highly popular with passengers. Bruce Ismay and William Pirrie, together with the Harland & Wolff ship designers Alexander Carlisle (Pirrie’s brother-in-law) and Thomas Andrews (a nephew of Pirrie) responded with a plan for ships that would be even bigger and better. There would be three of them, enough to maintain a regular each-way service: Olympic (1911), Titanic (1912) and Britannic