6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

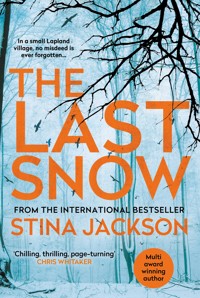

A chilling and addictive thriller about a dark mystery at the heart of a small town, perfect for readers of Will Dean and Maria Adolfsson. Selected as a The Times best crime books of 2021 ________________________ What secrets are hidden within the walls of a desolate farmhouse in a forgotten corner of Sweden? Early spring has its icy grip on Ödesmark, a small village in northernmost Sweden, abandoned by many of its inhabitants. But Liv Björnlund never left. She lives in a derelict house together with her teenage son, Simon, and her ageing father, Vidar. They make for a peculiar family, and Liv knows that they are cause for gossip among their few remaining neighbours. Just why has Liv stayed by her domineering father's side all these years? And is it true that Vidar is sitting on a small fortune? His questionable business decisions have made him many enemies over the years, and in Ödesmark everyone knows everyone, and no one ever forgets. Now someone wants back what is rightfully theirs. And they will stop at nothing to get it, no matter who stands in their way...

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Also by Stina Jackson

The Silver Road

First published in Sweden as Ödesmark

by Albert Bonniers Förlag, Stockholm, in 2020.

Published in hardback in Great Britain in 2021 by

Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Stina Jackson, 2020

The moral right of Stina Jackson to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book isavailable from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 1 78649 734 5

Trade paperback ISBN: 978 1 83895 215 0

E-book ISBN: 978 1 78649 735 2

OME ISBN: 978 1 83895 219 8

Printed in Great Britain

Corvus

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

For mamma and pappa

Where you come from is gone,where you thought you were going to never was there, and where you are is no good unless you can get away from it.

Flannery O’Connor, Wise Blood

PART I

EARLY SPRING 1998

The girl moves through the night. A pale moon smiles down on her as she zigzags between the puddles left behind by the melting snow. The twenty-four-hour filling station casts its neon light over the desolate landscape and she goes in and buys a can of Coke and a packet of Marlboro Red. The assistant working the night shift has kindly eyes which make her turn away. She walks out and stands beside the illuminated car wash, lights a cigarette and blows smoke up into the night sky. Her attention is caught by the haulage truck parked beyond the pumps. A man is asleep in the driver’s seat. He is wearing a dark cap and his head is nodding up and down in time to his breathing. She drops the half-smoked cigarette on the ground and crushes it with her foot. The pools of water glisten like oil in the arc lights as she makes her way over the tarmac. There is the hum of a few solitary cars in the distance but otherwise it is silent. The anticipation sends a shiver down her spine. When she reaches the truck she grabs the side mirror and heaves herself up the steps until her face is on a level with the sleeping man’s. Close up he is younger than she first thought, with a shiny earring and cheeks shadowed by a stubbly beard.

She watches her own white knuckles move closer to the window. It is a gentle knock but even so the man wakes up with a violent start that knocks off his cap, revealing his thinning scalp. He blinks at her and it takes him a while to lower the window.

‘What’s going on?’

The adrenalin makes it hard to smile. Her hand gripping the mirror has already started to ache.

‘I just thought you might want some company.’

He stares at her, open-mouthed. At first it looks like he’s going to protest but then he nods towards the passenger door.

‘Come on in, then.’

She walks around the truck, the expectation growing inside her. She turns her head to check for any eyes in the shadows but all she can see is the garage assistant and he’s not looking out. It’s nearly 2 a.m. and there are no other cars around. If anything should happen, there are no witnesses.

The man is breathing heavily through his mouth as she sits down.

‘And who might you be?’

‘Just a girl.’

The cabin smells of warm breath.

‘I can see that.’

He seems awkward, rubs his eyes with the palms of his hands and gives her a sidelong look as if she were a strange animal he didn’t want to annoy.

‘And what makes you want to sit here with me?’

‘You look lonely, that’s all.’

She challenges him with her eyes, thinks he looks afraid. That gives her courage.

He laughs and his fingers play nervously with his stubbly beard as he continues to watch her out of the corner of his eye.

‘So you’re not one of those who wants paying?’

She places a hand over his. Her silver rings shine like tears in the darkness between them and she hopes he can’t feel the blood pulsating through her veins.

‘No, I’m not one of those.’

There is plenty of room at the back of the cabin. He bends her over a bunk and his hands are heavy on her hips as he thrusts himself inside her. They don’t undress. Their trousers stay around their ankles, almost as if they are expecting to be discovered. She raises her eyes and sees a child smiling at her from a photograph. The child has its chubby arms wrapped around the neck of a chocolate Labrador and it looks as if they are both smiling. The girl lowers her eyes to the crumpled bedding instead. It isn’t long before he cries out and withdraws – quickly, so all the sticky fluid lands on the floor. She bends over and pulls up her knickers. All of a sudden she is dangerously close to crying and she keeps gulping to smother it.

The man seems wide awake. There is a new kind of confidence in his hands as he fastens his belt, like a teenager who’s just had his first lay. It amazes her how alike they are. The men.

They sit in the front of the cab, smoking. Beyond the massive windscreen the world is dark and damp. She feels sore but the feeling of wanting to cry has passed.

‘Where are you going now?’

‘Haparanda. And then back to Skåne again.’

His dialect sounds weird, almost like he’s singing.

‘You coming along?’ he asks.

She turns her head to blow out smoke.

‘I’m going further than Haparanda.’

His teeth gleam in the darkness. This isn’t something he has done before. She can already see the guilty conscience taking shape in him. His voice is trying to smooth out what has just happened. He nods toward the filling station.

‘I was thinking of getting myself something to eat. Do you want anything?’

‘A cinnamon bun would be good.’

‘Sure, leave it to me.’

He takes the keys from the ignition and smiles shyly at her as he opens the door and steps out. He looks slightly bow-legged as he walks and he ignores the splashes from the puddles. The girl watches him as he disappears into the shop, wondering whether to ride with him after all. She could get out at Luleå. She has heard it’s a pretty big town. And you can disappear in a town.

Dusk was the worst. The realization that yet another day has been wasted. A day like every other. She stood in her place behind the till and tried to ignore the darkness as it edged its way across the shop windows. Standing under the harsh fluorescent lights was like being on stage. People who stopped to fill up could see her there in the light, the weary movements, the indifference. The thin hair that wouldn’t grow beyond her shoulders and the false smile that made her cheeks ache. They could see her while she could just about make them out.

The filling station was in the middle of the community and she knew the name of practically every person who came through the door, but she didn’t know them. Maybe they thought they knew her. But she was aware of the whispering, at any rate. Björnlund’s daughter who’d had the world at her feet but never did anything about it. And now it was too late. Her beauty and her enthusiasm for life had begun to drain away. The song had gone quiet. The only thing she had achieved was the child, a boy, but how that had happened nobody could be sure as she’d never had a man in her life. Not as far as they knew, anyway. The boy had come out of thin air, and despite all the rumours that had circulated over the years it was never clear who the father was. It was an inconvenient concern that still led to disputes. The only thing the village could agree on was that Liv Björnlund would never be like other people. They might even have felt sorry for her had it not been for the money. It was hard to feel sorry for someone who was sitting on a fortune.

She drank cold vending-machine coffee and stole a look at the clock. The seconds beat time inside her forehead. On the dot of nine she would step off the stage, anyway. If she didn’t her brain would explode. But it was five past by the time the night-shift guy turned up. If he noticed how desperate she was he didn’t make anything of it.

‘Your dad’s out there, waiting,’ was all he said.

Vidar Björnlund was parked in his usual place by the diesel pump. He sat in his wreck of a Volvo, his claw-like hands painfully clamped on the steering wheel. In the seat behind him, like a shadow, sat Simon with his face in his mobile. She patted his knee before fastening the seat belt and for a brief second his eyes met hers. They smiled at each other.

Vidar turned the key and the Volvo coughed into life. The old motor had been born in the early nineties and was more suited for the scrapyard than the potholed country roads, but when she pointed that out to him he simply dismissed her.

‘She isn’t purring like a cat, but at least she’s purring.’

‘Don’t you think it’s time we bit the bullet and bought a new one?’

‘No, I don’t, dammit. Buying a new car is like using money to wipe your backside.’

Liv turned to Simon again. He seemed to take up the whole of the back seat with his long legs and his arms swelling under his jacket. The change had somehow taken place without her noticing. Suddenly one day there he was, a full-grown man. His chubby face had gone, leaving only sharp-edged cheekbones and a chin where a red-blond shadow grew thicker every day. There was no trace of her soft round boy. She tried to get his attention but he didn’t appear to notice and carried on frenetically punching keys with his thumbs, lost in another world from which she was denied access.

‘How was school?’

‘Good.’

‘School,’ snorted Vidar. ‘Nothing but a waste of time.’

‘Don’t start that again,’ said Liv.

‘They only learn three things in school. Drinking, fighting and chasing skirt.’

Vidar angled the rear-view mirror so he could see his grandchild.

‘Am I wrong?’

Simon hid his mouth under his collar but Liv could see he was smiling. He was more amused by the old man than she was. He had the ability to laugh away the things that made her boil with rage.

‘You’re only saying that because you didn’t get an education,’ she said.

‘What do I want with an education? I already knew how to drink and fight. And there was never any lack of skirt. Not when I was young.’

Liv shook her head and turned to look at the forest. She avoided the veiny hands and the old man’s breath that scalded the air between them. Soon the tarmac became gravel and the trees thickened. They didn’t meet any oncoming cars and beyond the headlights was only darkness. She undid the top buttons of her work shirt and started scratching her chest and throat. The itching always became worse on the way home, as if her body was trying to break free of her own skin in despair. The thousand ants in the roots of her hair and up her arms made her scratch until her skin bled. If Vidar and Simon noticed, they said nothing. Her behaviour was so familiar to them it wasn’t worth mentioning. The boy’s phone vibrated at regular intervals, demanding his constant attention. The old man sat with his trembling hands on the wheel, his jaws working. He preferred to chew on his words rather than share them.

When they reached Ödesmark the old familiar feeling washed over her, all the times she had jumped out of the car and run. Straight into the arms of the spruces she had fled, as if they could protect her. The village stood like a last outpost at the end of a road that no longer led anywhere. Twenty kilometres to the west it was swallowed up by the forest and the undergrowth, and the ruins of what had once been. If you drove a lap around the village you quickly got the feeling that the forest was biding its time before it swallowed that as well. The houses were a comfortable distance apart, separated by pine forest and marshland and the black eye of the lake that lay in the middle of it all, reflecting the desolation. There were fourteen farmsteads all told, but only five were inhabited. The rest brooded with their boarded-up windows and weather-beaten facades, well on their way to becoming overgrown.

Liv knew this land better than she knew her own insides. Her feet had worn tracks that snaked between the villages and she knew every fresh spring, cloudberry patch and forgotten well that lay slumbering out there. She knew the people too, even if she avoided them. She could identify the laughter and the smells carried on the wind, and she didn’t need to look to know whose car was driving over the gravel or whose chainsaw was shattering the peace. She heard the barking of their dogs, the bells of their cows. They both suffocated and sustained her. The land and the people.

Björngården, her childhood home, stood on a hill safely surrounded by forest, and from her room upstairs she could make out the black mirror of the lake down in the valley. Vidar had built the house before she was born and here she had remained, well into her adult years, although even as a child she had sworn she would never stay. And not only had she stayed, she had also allowed Simon to grow up in the same godforsaken place. Three generations under the same roof, the way they lived in the old days, in times of hardship. But there was no hardship now, apart from that created by people who needed others to cling to. And the more time that passed, the harder it became to lift their eyes above the treetops and envisage being anywhere else. Then it was easier to be slowly swallowed up together with the rest of the village.

Vidar swung in at the barrier and cleared his vocal cords.

‘Home, sweet home,’ he said, staring at the dilapidated house on the hilltop.

They watched as Simon climbed out and leaned over the padlock. They hardly recognized him from behind, with his broad shoulders and neck like an ox. When he raised the barrier Vidar coasted in slowly and as soon as they had passed Simon lowered it and locked it again. Liv tore at her stinging throat with her nails as they drove up to the farmhouse.

‘He’s not a child any longer,’ she said.

‘No, and a good job too.’

She glanced at her father and noticed that time had left its mark on him as well. Vidar had shrunk with age; his weather-beaten skin hung loose over the angular features and gave the impression that he was slowly wasting away from the inside. But the spark of life still shone fiercely in his eyes, two unavoidable flames as he watched her. She turned her head and met her own empty gaze in the car window. The twilight had long since burned itself out, leaving only darkness behind.

Liam Lilja studied himself in the broken mirror. A long crack in the glass ran like a scar right across his face, distorting his nose and cheekbone. The lower half was a scowl, the teeth white in the dark stubble. The upper half wasn’t smiling. The eyes stared back at him, insolent, as if they wanted to cause trouble. If they hadn’t been his own eyes he would never have tolerated anyone staring like that. Without looking away.

‘What the hell are you doing in there? Putting on make-up, or what?’ Gabriel’s voice came from the other side of the door.

‘Coming.’

Liam turned on the tap, put his hands under the cold flow of water and rinsed his face. A cut on his cheek stung and a tooth in his lower jaw ached, but he welcomed the pain. It gave the world more clarity.

Out in the illuminated shop the assistant’s eyes were on him. An older balding man, blinking nervously. Liam felt the irritation rise in his chest when he looked at the man. He felt his face harden and time slow down.

Gabriel thrust a packet of crisps at his chest, hard enough to crush the contents.

‘Breakfast,’ he said. ‘I bought cigs too.’

They sat in the car, ate crisps and drank ice-cold Coke. The sky was beginning to get light but the sun hadn’t lifted above the treetops. Gabriel devoured the giant bag of crisps in less than ten minutes and moved on to rolling a joint with greasy fingers.

‘I checked the plants yesterday,’ he said. ‘Two lamps are dead. We’ve got to get new ones.’

Liam crumpled up the crisp bag and started the engine.

‘That’s your thing now,’ he said. ‘I’m not a part of it any longer.’

‘Fucking great plants,’ said Gabriel, as if he hadn’t heard. ‘Best we’ve had so far. I think I’ll ask more for them.’

Liam stared at the cars parked by the other pumps. One woman in a passenger seat painted her lips and then yawned widely. Her mouth was a dangerous red circle. He wondered what kind of job she had, whether she had children. Maybe a house with a garden and swings. The driver, presumably her husband, returned from the shop and sank down behind the wheel. He had nondescript glasses and slicked-down hair. Liam lifted his hand and patted his own bushy hair, but it wouldn’t stay in place. It didn’t matter how hard he tried, he would never look like them. Like ordinary people.

They left Arvidsjaur behind them, following smaller roads that wound away from habitation and deeper into untouched territory. Large mirrors of water on either side reddened along with the sky. Gabriel smoked his joint with his eyes shut, only breaking the silence with his rattling cough. It sounded as if his ribs had come loose and were tumbling around in his chest. He had a scar on his lower lip that pulled down the left corner of his mouth, the result of being caught by a fishing hook when he was a child. Although Gabriel always insisted it was a knife wound. That story suited him better.

When the lakes came to an end there was only forest. It stood dense and dark beside the cracked tarmac, and Liam felt his guts churn.

‘Does he know we’re coming?’

Gabriel coughed. The smell of unbrushed teeth and weed filled the car.

‘He knows.’

An overgrown railway track appeared out of nowhere and followed them a short distance until it was buried again under the forest floor. They drove past an abandoned train station wrapped in the embrace of slumbering vegetation. Rusting carriages riddled with holes where plants and other life made their way out. Further on were the remains of a farm surrounded by empty paddocks, where ungrazed grass and dead flowers waited for the sun’s warmth to grow again.

The tarmac became gravel and Liam turned onto a series of tracks, each one smaller than the other. In the beginning he had always gone the wrong way, in the days before he had a driving licence and the car they were driving was hot-wired. Then the route to Juha’s place had seemed more like a labyrinth in the wilderness, and that was probably the whole point because Juha didn’t want to be found.

Beside a black, rippling stream an unpainted log cabin protruded from the trees. There was no electricity or running water here. Liam parked some distance away and they sat in silence, preparing themselves. A coil of smoke rose from the chimney and settled like a blanket over the trees. It would have been a tranquil scene if not for the dead animals. Two carcasses hung from the branches, skinned and headless. Enormous slabs of meat, gleaming in the light.

When they opened the car doors they were met by the sighing of the spruce trees and the gurgling water. Liam carried the plastic bag with the coffee and the weed, trying not to look at the hanging meat. For a split second he imagined they were human corpses Juha had mutilated and hung there.

Juha Bjerke, the lone wolf who had turned his back on people and seldom ventured into the village. Rumour had it that a hunting accident in the nineties was the reason. Juha had somehow shot and killed his own brother during a moose hunt. The police were never involved but Juha’s mother couldn’t bring herself to forgive him, and there were many who said he had done it deliberately, that envy had taken the upper hand. It had happened before Liam was born and the only thing he knew for sure was that Juha shunned people as much as they shunned him.

A dog came hurtling out of the undergrowth and they stood still while it sniffed at them, hackles raised. A low growl came from its throat, although it should recognize them by now. Gabriel spat in the grass.

‘I could shoot that fucking animal.’

The dog trotted ahead of them as they made their way to the house.

‘You go first,’ said Gabriel. ‘He likes you best.’

Liam felt himself tense up as he approached the cabin. Visits to Juha always made him feel paranoid, even though they hardly ever saw the man. Often all he did was stick out his arm long enough to hand over the money and take the delivery. He wasn’t much for small talk. But even so, Liam’s muscles tensed every time the solitary building loomed up before him.

It was the same for Gabriel. He had fallen silent and lagged a few paces behind Liam. Perhaps it was the isolation that did it, and being on Juha’s territory. Or else it was the tragedy that hung over the solitary man like a storm cloud. Despite the fact that many years had passed since the accident, the grief was etched deeply into his face. There was something frightening about a person who had lost everything.

A deer skull was loosely nailed to the front door and it juddered when Liam knocked. The dog panted at their feet and from the cabin they heard the sound of feet shuffling over worn floorboards. The door opened a fraction, revealing a skinny shadow in the crack. Inside, an open fire was burning and the shadows from the flames flickered in the dim light. Juha stuck out his head and grimaced at the dawn. He was old enough to be their father, somewhere between forty and fifty, but his body was hard and sinewy like a young man’s. His long hair hung in a ponytail down his back and his face had been lined by weather and misfortune.

Without a word he took the bag from Liam, leaned over, and stuck his nose in the weed to convince himself that it was genuine before handing over the cash. Liam only had to look at the money to see it wasn’t enough. It took him by surprise. Juha Bjerke wasn’t the kind to give them grief about payments.

‘This is only half.’

A peculiar light filled Juha’s eyes.

‘What?’

‘You’ve got to pay all of it. This is only half.’

Juha glided back into the darkness with a catlike movement. He held one hand behind his back as if he was hiding something there. A weapon, maybe. Liam felt his heart begin to race.

‘Come in for a minute,’ said Juha from the darkness. ‘So we can have a chat.’

Liam put the wad of notes in his pocket and shot a sidelong glance at Gabriel. He looked pale and confused. This was something new; Juha had never invited them in before. Once he got what he wanted he usually shooed them away as if they were stray dogs he couldn’t afford to feed. This was the first time he had invited them over the threshold. The fire was burning inside. Liam could make out the hunting rifles in the firelight, hanging in neat rows beside the open fire. On the hearth stood a row of small rabbit skulls, gaping helplessly at them.

‘Come in, then,’ said Juha. ‘I won’t bite.’

For a few eternal minutes everything stood still. There was only the crackling of the fire and the wind in the trees. Juha’s gappy smile challenged them from inside the room. Liam filled his lungs with fresh air before stepping in. The heat in the small space enveloped him, his nose was filled with weird smells and his eyes struggled to see everything that was hidden in the gloom. It was like stepping straight into a hole. A dark, quivering trap.

Liv was alone with the dawn. The light filtered through the naked birches and settled like a glowing crust over the black forest. She had the farmhouse behind her and avoided looking back at it. Her frozen breath was a shield against the world. She didn’t see the lights go on or hear anyone call her name. Not until a scrawny Lapphund came racing out of the undergrowth and danced in circles around her did she hold the axe still and turn around.

Vidar was standing on the veranda, his eyes like black slits.

‘Come and eat,’ he shouted in his cracked voice.

Then he was gone. Liv brushed off her jacket and started to walk reluctantly towards the house, her footsteps like drumbeats in the silence.

The old man and the boy were in the kitchen, sitting in an aroma of coffee. Vidar’s hands had locked during the night and when morning came his fingers were rigid claws that could hardly lift the cup to his mouth. It was Simon who sliced the loaf and spread the butter for him, with deep concentration.

‘Have you taken your tablets, Grandad?’

Vidar carried on chewing his bread. He wanted nothing to do with medication and if it weren’t for Simon lining up the tablets in a neat rainbow in front of him each morning, he would never take them.

‘You’re worse than an old woman, the way you nag.’

But Vidar swallowed the tablets one by one, and afterwards gave Simon a gentle pat on the hand which was a larger version of his own, and the boy smiled down at the table. Liv turned her eyes away, wondering where the boy got his goodness from, his inner light. It wasn’t from her.

She went up to her room to change. The door to Simon’s room was ajar and her eyes were drawn into the gloomy interior. The duvet had slipped from his bed and was lying in a heap on the floor beside islands of dirty clothes and books that wouldn’t fit on the shelves. The blackout blind was pulled down and the only light in the room came from the old PC that hummed on the desk. She had bought it for him despite Vidar’s protests, and the computer had become something of a friend to the lonely boy. A whole life went on in there that she knew nothing about.

She stood with her face in the gap, breathing in the smell of adolescence, sweaty socks and anxiety. She checked for their voices down in the kitchen before pushing open the door and going in. Her knees creaked as she picked up the duvet, and dust swirled around the room. Something glinted under the bed and when she bent down she saw it was a glass bottle without a label. The smell of alcohol was so strong she had no need to unscrew the cap to know what was inside. Homebrew of some kind, strong enough to make your eyes water. Vidar’s maybe.

‘Shit, Mum, what are you doing? You can’t go snooping through my stuff.’

Simon stood in the doorway, his face black with rage. Liv straightened up, the bottle in her hand. The cool glass was smooth against her skin.

‘I was going to make your bed,’ she said. ‘And found this.’

‘It isn’t mine. I’m looking after it for a friend.’

They both knew it was a lie, there were no friends. But she couldn’t say that. Liv dusted off the bottle and stood it gently on the desk next to the computer. Thoughts flowed in time to her pulse. He was seventeen years old, there was no point in arguing about it. It might even be a good sign that he was doing typical teenage things.

‘Which friend?’ she asked.

‘None of your business.’

They looked at each other for a long time. A furrow had formed between his eyebrows and it made him look like Vidar. Even so it was herself she saw in the boy’s face. Defiance, the hunger for something else, for freedom. If it hadn’t been for him she wouldn’t be standing here, in the house where she was born. She would have been somewhere else, far away. Maybe he knew it, that he was the reason. Maybe that was why the distance between them had grown wider. She wondered if he had actually found friends, maybe the worst kind, kids who drank and got into fights. Or whether he sat alone in the blue light of the computer, drinking all evening. Either alternative made her feel weighed down.

Simon reached out for his backpack. The angry flush had run from his cheeks.

‘I’ll be late for school.’

She nodded.

‘We’ll talk about it this evening.’

‘I don’t want you in my room while I’m out.’

‘I’m leaving now.’

He waited until she had left the room and made a show of shutting and locking the door before going downstairs. Liv followed him; she looked at the downy boyish neck and thought of all the times she had buried her face there and filled her lungs with his smell. All the nights she had wrapped her body protectively around his, rested a hand between his delicate shoulder blades just to reassure herself that he was breathing, that he wouldn’t die and leave her. That was so long ago now, another time.

They stood at the kitchen window and watched as he walked to the bus. Liv and the old man. They kept their eyes on the boy’s gangly figure until the forest swallowed him up.

‘I reckon he’s got a woman,’ Vidar said.

‘Really?’

‘Yep. I can smell it. He smells different.’

‘I haven’t noticed.’

Vidar put a sugar cube between his teeth, sucked coffee through it from his saucer and gave her a meaningful look.

‘He takes after his mother, you mark my words. Soon he won’t be coming home at night.’

It was hard to breathe in Juha Bjerke’s cabin. Liam and Gabriel sat at an unsteady table while the skinny man paced the floor in front of them. Small clouds of dust and pine needles whirled around his boots and the smoky air stung their eyes. His gaze went from one to the other but they couldn’t catch his eye.

‘You’ll have to forgive me,’ he said. ‘I’m not used to folk.’

Liam tried to hide the uneasiness that was pulsing through his body. He glanced at Gabriel. His brother seemed amused. There was the hint of a smile on his lips and his eyes were taking in the cabin, absorbing the strange contents and the hunting trophies. A knife was stuck in the tabletop and dried blood had left a dark shadow on the scratched surface. The head of an animal hung like a curtain in the only window and it was hot and stuffy in the crowded space. Juha stood to one side of the log fire and his eyes seemed to burn as he looked at them. His voice was hoarse, as if the vocal cords had started to go rusty in his throat. That must be what happens when there’s no one else to talk to.

‘You’re the kind of lunatics who hunt foxes on snowmobiles,’ he said. ‘I can tell just by looking at you.’

‘You don’t know what you’re talking about,’ said Liam. ‘Do we look like freaking hunters?’

‘But you hunt money, don’t you? That’s what your life consists of: drugs and a quick buck.’

Liam felt the vibration from Gabriel’s legs as he drummed them on the floor. Neither of them spoke.

‘You don’t turn up with coffee and a smoke for an old man out of the goodness of your hearts, do you? You want paying for your trouble.’

‘We don’t do charity, if that’s what you mean,’ said Gabriel. ‘Fair’s fair.’

Juha cackled. Out of the corner of his eye Liam saw the knife. He would only have to reach out his hand and it would be his. That made him feel calmer.

Juha suspended the coffee pot over the fire.

‘You’re hungry,’ he said. ‘And I like that. I was hungry too, once. But if you’ve been starved for long enough, you don’t hear your stomach complaining any longer. It goes deadly quiet.’

Despite his rusty vocal cords his voice had a melody to it, as if he would rather be singing the words.

‘I knew your dad when I was younger,’ he went on. ‘We were at school together. He was one hell of a man. Evil-tempered as a badger, he was. Slippery too. But if you were in trouble, he’d lend a hand.’

‘The old guy’s dead,’ said Gabriel.

‘Don’t I know it. No one escapes cancer. Once it gets its claws into you it’s thank you and goodbye.’

He had mentioned his friendship with their father before, the first time he wanted to buy weed, in an attempt to win their trust. Liam had a feeling the same thing was happening now, that Juha was using their dead father to win their confidence.

Juha scratched his sunken chest and his eyes were on the flames as the smell of coffee filled the room. Liam and Gabriel looked at each other, waiting.

‘I’ve got a job for you,’ Juha said at last. ‘If you’re interested.’

‘What kind of job?’ Gabriel asked.

Juha smiled as he poured out the coffee and carefully placed two steaming mugs on the table in front of them. A massive axe had pride of place against the fireplace, its blade glinting in the firelight. Liam’s stomach began to churn. The stifling heat and the smell of the animal heads was making him feel sick.

Juha stood at one end of the table, rocking backwards and forwards. He made a whistling sound as he blew on his coffee.

‘There’s an unworked gold mine not far from here. It’s just sitting there, waiting for some poor starving creatures like yourselves.’

His jumper lay like a loose skin over his torso and was discoloured by time and sweat. His trousers had long rips in the fabric and pale flesh showed underneath. He gave off an odour of pine needles and damp leaf mould. With a sudden movement he tugged the knife out of the tabletop and began cleaning his nails with it. Liam glanced at the door. Only three paces and he would be out in the fresh air again.

‘We’ll have our money,’ he said. ‘You’ve had your weed and like my brother says, we’re not running a charity.’

‘I had a brother as well, once,’ said Juha. ‘We were exactly like you two, always together. Unbeatable, we were, my brother and me, with the whole world at our feet. But then the son of a bitch went and died, and that’s when I realized there weren’t any rules. Fate laughs in your face.’

He grimaced, as if in pain, and said nothing for a long time. Everything was still. There was only the fire, living its own life behind his back, flaring and crackling. It was hard to read his face in the dull light, hard to keep one step ahead. Gabriel’s foot found Liam’s under the table and gave it a kick.

‘Tell us more about this gold mine,’ he said. ‘Where is it?’

Juha’s smile was like a scowl.

‘Do you know a Vidar Björnlund from Ödesmark?’

‘Everyone knows that old skinflint.’

‘He might live like he’s as poor as a church mouse but he’s got money all right, and then some. He’s accumulated piles of it through the years, the tight-fisted bastard. And he doesn’t trust the banks, neither. Most of it is stashed away in a safe in his room. He’s old and worn out. Robbing him would be as easy as taking sweets from a baby.’

Gabriel raised his eyebrows.

‘How come you know all this?’

‘I know it because we did some business together way back. At a time when I was still too stupid to realize that he tricked decent folks out of their land and sold it on to the logging companies. A greedy bastard, that Vidar. No one wants to do business with him these days. All he’s got is his daughter Liv, though servant would be a better name. Never had a life of her own, poor girl. Still living with her dad out there at Ödesmark, even though she’s got her own kid to look after. Or maybe that’s why.’

Juha turned his head and spat into the fire. The colour had deepened in his cheeks and his voice shook as he went on:

‘Vidar is the only one with the code to the safe. When it comes to his money he doesn’t even trust his own family. The daughter and grandchild dance to his tune, both of them. No say at all as long as he’s alive. They won’t stand in your way, I promise you that. So you leave them alone, you hear me? There’s no reason to lay a finger on the daughter or the grandchild. All you’ve got to do is catch the old man unawares and the cash is yours.’

Liam took a look at Gabriel. His nostrils were flaring, his dull eyes had taken on a new lustre.

‘Why don’t you go there yourself, if it’s that easy?’

A painful expression crossed Juha’s face and made him look older.

’I can hardly get myself to the village these days. Can’t bear to see people, let alone go and steal money. Better to give two capable young lads such as yourselves the chance. I know you can do it.’

‘You’ve run out of money, haven’t you?’

‘No, dammit, I manage all right. Let’s just say I’m heartily sick of Vidar Björnlund. That fool has had his own way long enough. It’s about time he learned a lesson or two.’

The old man fixed his eyes on Liam and drew an imaginary knife across his own throat. It looked comical but Liam felt a shiver run down his back. He looked at Gabriel, saw the new light in his face and knew he had already made up his mind. It didn’t take much to arouse his hunger. The constant dream of easy money. As for himself, he wasn’t so easily convinced. An image of Vanja came to mind, all the dreams he had woven for her even before she came into the world. Dreams of normal life, a house with many rooms, all the surfaces clean from shame. He thought of the incubator she had been in for days after her birth, a blind little bundle with tubes in every opening while the drugs pulsed around her tiny body. He hadn’t been allowed to touch her, only to look on as she lay there, fighting. That image would always be his driving force.

‘What do you want from us?’ asked Liam.

‘What do you mean?’

‘You’re telling us this because you want something in return, right?’

‘I don’t want a penny from you. All I want is to see Vidar Björnlund brought to his knees once and for all. I want to see him lose the fortune that should never have been his in the first place.’

Liam pushed his chair back and stood up. Juha stood staring at him, weighing the knife in his hand.

‘And you’re sure there’s a safe?’

‘As sure as I know the sun comes up in the morning and goes down at night. Wait, I’ll show you something.’

Juha faded into the gloom, turned his back to them and began rummaging in a chest that was standing on the floor. Clouds of dust flew up like smoke around him and filled their nostrils. Eventually he grunted and held something in the air, a yellowing piece of paper marked by time and greasy fingers. With a triumphant movement he put it on the table between them.

‘What’s this?’

‘You’ve got eyes, haven’t you? It’s a chart.’

It looked like a rough floor plan – hall, kitchen and one room, shakily captured in black ink. Doors and windows meticulously marked, black arrows leading to the room. There, in a corner, someone had put a thick black cross. Juha leaned over the table and stabbed the knife so hard into the centre of the cross that the shaft vibrated.

‘There she is,’ he said. ‘The answer to your dreams.’

Liv drank her coffee standing by the sink to avoid sitting next to her father. Vidar was staring out through the window, watching for signs of life on the desolate gravel road. He was warmly dressed and had his knife in his belt, even though his hands rarely let him use it these days. He never watched TV or read books, never did crosswords or bet on horses. His days consisted of drinking coffee and keeping watch on the village. Even if he refused to have anything to do with the neighbours, he had to know what they were up to. He kept them under the same ruthless scrutiny as he did his own family. Nothing slipped past the old man. His cloudy eyes still saw everything.

Liv didn’t mention the bottle she had found in Simon’s room. Vidar would discover it all in good time, anyway.

A car drove by down on the road. Vidar raised himself out of his chair and his joints creaked. He craned his neck, hungrily.

‘Look at that. Karl-Erik’s out and about again. They should take the bugger’s driving licence away from him.’

‘Sit down and stop staring.’

‘He’s never sober long enough to drive a car. He’ll end up killing some poor soul, you wait and see.’

Liv looked down at the muddy gravel road and the sun reflecting in the meltwater. She heard Karl-Erik’s car disappear out onto the main road. She knew Vidar’s hatred of the neighbours was on account of his loneliness. He no longer knew how to approach people. Their proximity scared him, made him toxic.

‘There’s a problem with the chainsaw,’ she said.

‘There is?’

‘I don’t intend chopping all the logs by hand.’

‘The lad can help you. He’s got to do something with those muscles he’s built up.’

Vidar chewed his bread slowly. He only used butter in the mornings, and nothing else. Fillings had to wait until lunch. Liv poured out more coffee and studied the miserable pile of logs outside. The bright red handle of the axe was like a piercing scream in the greyness. A chainsaw was another superfluous item, and if she wanted a new one she would have to buy it herself. A man who denied himself a slice of cheese would never allow himself a new chainsaw.

With a calloused hand Vidar smoothed the newspaper that lay on the table in front of him. The houses for sale she had circled with a red pen stared back at him. She did it for his sake, so he would understand that they were on their way out of here, she and the boy. When she started doing it, many years ago now, he used to get annoyed, but now he only made a joke of the whole thing.

‘You don’t want to be living in the town. It’s all exhaust fumes and litter and empty-eyed people. Out here you can at least see the stars at night.’

When he got up to fetch more coffee she made her escape to the bathroom. She peed in the rusty toilet and afterwards stood with her hands on the cracked basin for a long time. The mirror was also damaged, a spider’s web of cracks in one corner. She avoided meeting her own reflection; the tired mouth and the sad eyes just made her more tired and sad. It wasn’t only the house that was falling into ruin; her face was also full of cracks. She heard Vidar humming in the kitchen. He was the one who was old, he was the one who should be thinking of death, yet she was the only one who did. Every day she thought it couldn’t be long, that she only had to bear it for a few more years. Then life would start.

When she returned to the kitchen Vidar was sitting in his chair again. It was like an unspoken agreement they had, a kind of dance, so if one was sitting at the table, the other stayed by the sink. If one was moving about the floor, the other stood still, almost as if the house couldn’t tolerate too much movement at the same time. Despite the fact that they had lived under the same roof since the day she was born, the distance between them had only grown.

A quad bike drove along the road and Vidar ducked behind the curtain. A dayglo jacket flashed between the pines.

‘Well, what do you know?’ he said. ‘Old Modig’s gone and bought himself another new toy. The man hasn’t got change for a bus but it doesn’t stop him buying more things.’

‘How do you know it’s new?’

‘I’ve got eyes in my head, haven’t I? The old one was black. This one’s red.’

Liv walked over to the window. Douglas Modig had stopped by the barrier and was raising his hand. She waved back.

‘Maybe I can borrow his chainsaw,’ she said. ‘Until we get a new one.’

Vidar started to cough. The catarrh rattled in his lungs.

‘Like hell you will,’ he said, when he had recovered. ‘I’m not having that bastard on my land. I’d rather chop the wood myself.’

She was soon back at the chopping block. The spring sunlight was so bright she had to close her eyes each time she lifted the axe, and when it fell it was her father’s head she split.