5,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

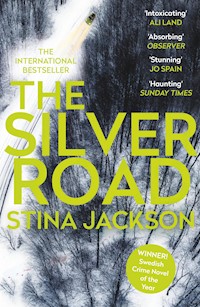

Even the darkest journey must come to an end... ____________ 'Haunting, intoxicating' Ali Land, author of Good Me, Bad Me 'Deeply affecting' Chris Whitaker, author of All the Wicked Girls ____________ Three years ago, Lelle's daughter went missing in a remote part of Northern Sweden. Lelle has spent the intervening summers driving the Silver Road under the midnight sun, frantically searching for his lost daughter, for himself and for redemption. Meanwhile, seventeen-year-old Meja arrives in town hoping for a fresh start. She is the same age as Lelle's daughter was - a girl on the brink of adulthood. But for Meja, there are dangers to be found in this isolated place. As autumn's darkness slowly creeps in, Lelle and Meja's lives are intertwined in ways, both haunting and tragic, that they could never have imagined. ____________ **WINNER OF THE 2018 SWEDISH ACADEMY OF CRIME WRITERS' AWARD FOR BEST SWEDISH CRIME NOVEL** **WINNER OF THE 2019 GLASS KEY AWARD**

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

Originally published in Sweden as Silvervägenby Albert Bonniers Förlag in 2018.

First published in Great Britain in 2019 by Corvus,an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Stina Jackson, 2019English translation copyright © Susan Beard, 2019

The moral right of Stina Jackson to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

The moral right of Susan Beard to be identified as the translator of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is availablefrom the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 1 78649 730 7

Trade Paperback ISBN: 978 1 78649 732 1

OME ISBN: 978 1 78649 822 9

Ebook ISBN: 978 1 78649 731 4

Printed in Great Britain

Corvus

An Imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

To Robert

PART I

It was the light, the way it stung and burned and tore at him, hung over the forests and the lakes like an incentive to go on breathing, like a promise of new life. The light, that filled his veins with an urgency and robbed him of sleep. It was still only May, but he lay awake as dawn filtered through fibres and gaps. He could hear the melting frost seeping out of the ground as winter bled away, and streams and rivers rushing and surging as the fells shed their winter covering. Soon the light would consume every night, invading, dazzling, shaking life into everything that slumbered beneath the rotten leaves. It would fill the buds on the trees with warmth until they burst open, and the forest would fill with mating calls and the hunger cries of newly hatched life. The midnight sun would drive people from their lairs and fill them with longing. They would laugh and make love and become crazy and violent. Some might even disappear. They would be blinded and disorientated. But he didn’t want to believe that they died.

He smoked only while he was searching for her. Lelle saw her in the passenger seat every time he lit another cigarette, the way she grimaced and fixed her eyes on him over the rim of her glasses.

‘I thought you’d given up?’

‘I have given up. This is just a one-off.’

He could see her shake her head, scowl and bare her teeth, the pointy canines that embarrassed her. Her presence was more palpable then, as he drove through the night and the daylight clung on. Her hair that was almost white when the sun caught it, the dark splash of freckles on the bridge of her nose that she had tried to disguise with make-up in recent years, and her eyes that saw everything, even though she gave the impression she wasn’t looking. She was more like Anette than she was him, and that was just as well. The beauty genes certainly hadn’t come from him. She was beautiful and that wasn’t just because he was biased, people had always turned to look at Lina, even when she was very little. She was the kind of child who would bring a smile to the most jaded of faces. But these days nobody turned to look at her any more. No one had seen her for three years – at least, no one who was prepared to say it openly.

His cigarettes ran out before he reached Jörn. Lina was no longer sitting in the seat beside him. The car was empty and silent and he had almost forgotten he was driving, eyes on the road but taking nothing in. He had been travelling along this main road, known as the Silver Road, for such a long time that he knew it like the back of his hand. He knew every bend and every gap in the wildlife fencing that allowed moose and reindeer to cross if they had a mind to. He knew where rainwater collected on the surface and where mist drifted up from the tarns and distorted his vision. The road’s sole purpose had disappeared with the closure of the silver mines, and it had become treacherous after years of neglect and deterioration. But it was also the only road that connected Glimmersträsk with the other inland communities, and however much he detested the cracked tarmac and the overgrown drainage ditches that stretched out behind him, he would never abandon it. This was where she had disappeared. This road had swallowed up his daughter.

No one knew that he drove at night, searching for Lina. Or that he chain-smoked and put his arm round the passenger seat and chatted with his daughter as if she were actually there, as if she had never disappeared. He had no one to tell, not since Anette left him. She said it was his fault from the very beginning. He was the one who had given Lina a lift to the bus stop that morning. He was the one to blame.

He reached Skellefteå at about 3 a.m. and stopped at Circle K for fuel and to fill his flask with coffee. Despite the early hour, the lad behind the counter was bright-eyed and cheerful, with red-blond hair combed to one side. He was young, maybe nineteen, twenty. The same age Lina was now, although he found it hard to imagine her so grown up. He bought another pack of Marlboro Lights, despite his guilty conscience. His eyes fell on a display of mosquito repellent beside the till. Lelle fumbled with his bank card. Everything reminded him of Lina. She had reeked of mosquito repellent that last morning. It was actually the only thing he remembered, the way he had wound down the window to get rid of the smell after dropping her off at the bus stop. He couldn’t recall what they had said to each other that morning, whether she was happy or sad, or what they had eaten for breakfast. Everything that happened afterwards took up too much room, and only the mosquito repellent remained. He had said as much to the police that evening – that Lina stank of mosquito repellent. Anette had stared at him as if he were a total stranger, someone to be ashamed of. He remembered that, too.

He opened a new pack and kept the cigarette in his mouth until he was back on the Silver Road, going north this time. The homeward stretch always went faster, felt bleaker. Lina’s silver heart hung from its chain over the rear-view mirror and reflected the sun. She was sitting next to him again, her blonde hair falling like a curtain over her face.

‘Dad, you do know you’ve smoked twenty-one cigarettes in only a few hours?’

Lelle knocked the ash out of the window, blowing the smoke away from her.

‘That many?’

Lina rolled her eyes as if she were calling on higher powers.

‘Did you know every cigarette takes nine minutes off your life? So this evening you’ve shortened your life by one hundred and eighty-nine minutes.’

‘You don’t say,’ said Lelle. ‘But what have I got to live for, anyway?’

The reproach clouded her pale eyes as she looked at him.

‘You’ve got to find me. You’re the only one who can.’

Meja lay with her hands on her stomach and tried not to listen to the sounds. The hunger that growled under her fingers, and the others, the nauseating sounds that came up through the gaps in the floorboards. Silje’s heavy panting and then his, the new man’s. The squeaking of the bed and then the dog barking. She heard the man yell at it to go and lie down.

It was the middle of the night by now, but the sun was still shining strongly in the little triangle-shaped room. It fell in warm, gold shafts over the greying walls and revealed the pattern of capillaries under her closed eyelids. Meja couldn’t sleep. She kneeled beside the low window and brushed away the cobwebs with her hand. There was only blue night sky and blue tinted forest as far as the eye could see. If she craned her neck she could see a slice of lake down there, black and still. Enticing, almost. She felt like a captured princess in a fairy tale, locked inside a tower surrounded by deep, dark forest, doomed to listen to the sex games of her wicked stepmother in the room below. Except Silje wasn’t her stepmother, but her mother.

Neither of them had been to Norrland before. During those long hours on the train heading north the doubt had plagued them both. They had argued and cried and sat in lengthy periods of silence as the forest thickened outside the window and the distance between stations became longer and longer. Silje had sworn that this would be the last time they moved. The man she had met was called Torbjörn and he owned a house and some land in a village called Glimmersträsk. They had met online and talked forever on the phone. Meja had heard his monosyllabic Norrland way of speaking and seen pictures of a man with a moustache and thick neck, and eyes like slits when he smiled. In one photo he was holding an accordion and in another he was leaning over a hole in the ice, holding up a fish with red scales. Torbjörn was a real man, according to Silje. A man who knew how to survive in extreme conditions and who could look after them.

The train station where they eventually got out was nothing more than a hut among the pines, and when they tried the door it was locked. No one else had got out and they stood feeling helpless in the slipstream of the train as it pulled away and vanished among the trees. The ground vibrated for a long time under their feet. Silje lit a cigarette and started to drag the suitcase over the crumbling platform, while Meja stayed where she was, listening to the rustle of the trees and the whine of a million mosquitoes. She felt a scream begin to take shape in the pit of her stomach. She didn’t want to follow Silje, but she didn’t dare stay where she was. On the other side of the track the forest loomed, dark green verging on black, like a curtain against the illuminated sky, and a thousand shadows moved among the branches. She couldn’t see any animals, but the feeling of being watched was as powerful as if she had been standing in the middle of a town square. There was no doubt they saw her, hundreds of pairs of eyes, taking her in.

Silje had already made her way to the neglected car park where a rusty Ford was waiting. A man with his face shadowed by a black cap was leaning against the bonnet. He stood up when he saw them coming, revealing the wad of snus tobacco in his mouth as he smiled. Torbjörn looked bigger in real life, more solid. But there was something awkward and inoffensive about the way he moved, as if he were unaware of his own size.

Silje dropped the case and clung to him like he was a lifebuoy in the middle of this sea of forest. Meja stood to one side and looked down at a crack in the asphalt where some dandelion leaves had found a way through. She could hear them kissing, hear the tongues rooting around.

‘This is my daughter, Meja.’

Silje wiped her mouth and waved her hand in Meja’s direction. Torbjörn studied her from under the peak of his cap, saying in his abrupt way that she was welcome here. She kept her eyes pinned to the ground to emphasize that this was happening against her will.

His car stank of wet dog, and a rough greying animal skin was spread out in the back. Yellow stuffing had started to bulge out of one of the seat backs. Meja sat on the very edge of the seat and breathed through her mouth. Silje had told her that Torbjörn was well-off, but judging from appearances so far that was an exaggeration. There was nothing but gloomy pine forest lining the road to his house, interspersed with areas of ground bare from felling. Small, isolated lakes shone like teardrops among the trees. By the time they reached Glimmersträsk there was a burning lump in Meja’s throat. Torbjörn had his hand on Silje’s thigh, lifting it only to point out things he thought were of interest: the small ICA supermarket, the school, pizzeria, post office and bank. He appeared immensely proud of it all. The houses themselves were large and scattered. The further they drove, the greater the distance between the buildings. Forest and fields and pastures lay in between.

From time to time there was the sound of a dog barking in the distance. In the front seat Silje’s cheeks had turned red and shiny.

‘Look, how lovely, Meja. Like something out of a story!’

Torbjörn told her not to get excited, that he lived on the other side of the swamp. Meja wondered what that meant. The road in front of them narrowed and the forest crept closer, and a heavy silence filled the car. Meja found it hard to breathe as she watched the soaring pines flicker past.

Torbjörn’s house stood alone and isolated in a forest clearing. The two-storey building might have been impressive once, but now its red paint was peeling and it gave the impression of sinking into the ground. A scraggy black dog stood at the end of its chain and barked at them when they got out of the car. Meja’s legs felt unsteady as she looked around her.

‘Here she is,’ said Torbjörn, flinging his arm wide.

‘So silent and peaceful,’ Silje said, but the delight had gone from her voice.

Torbjörn carried in their bags and put them on the filthy black floor. It stank in there, too, of stale air and soot and ingrained fat. Shabby upholstery on furniture from a forgotten decade stared back at them. The brown-striped wallpaper was hung with animal horns and knives in curved sheaths, more knives than Meja had ever seen, and the place was full of dust and inescapable smells. Meja tried to catch Silje’s eye, but failed. She had glued that smile to her face, the one that meant she was prepared to put up with almost anything, and that she was far from admitting she had made a mistake.

The moaning from the ground floor had stopped, leaving space for the birds. Never before had she heard such birdsong. It sounded hysterical, unsettling. The roof sloped and formed a triangle above her head, and hundreds of knotholes were watching her. Torbjörn had called it the triangle room when he stood on the stairs indicating where she was to sleep. Her own room on the upper floor. It was a long time since she’d had a room of her own. Mostly she’d had only her own two hands to stop the noises. The noises of Silje and her men – the loud sex and the arguments. Always the arguments. It didn’t matter how far away she and Silje moved, the noises always caught up with them.

Lelle didn’t notice the tiredness until he swerved off the road and the tyres rumbled under him. He lowered the window and slapped his face hard, making his cheek sting. The seat beside him was empty. Lina had gone. All this driving about at night – she really wouldn’t have approved of that either. He put another cigarette in his mouth to keep himself awake. His cheeks were still glowing from the slap when he arrived home in Glimmersträsk. He pulled up by the bus stop and parked, looking disapprovingly at the innocuous-looking bus shelter that was embellished with marker-pen graffiti and bird droppings. It was early dawn and the first bus wasn’t due for a while. Lelle climbed out of the car and walked over to the wooden bench covered in scratches. There were sweet wrappers and globs of chewing gum on the ground. The night sun shone in the puddles, but Lelle couldn’t recall it raining. He trudged a couple of times around the shelter, then positioned himself as usual where Lina had stood when he had reversed the car. Then he leaned his shoulder against the dirty glass just as his daughter had done. Nonchalantly, almost, as if she wanted to emphasize that this was no big deal. Her first real summer job. Planting spruce trees up in Arjeplog, earning good money until the autumn term started. Nothing special about that.

It was his fault they were early. He was the one who was afraid she would miss the bus and arrive late for her first day at work. Lina hadn’t complained, because the June morning warmed and was alive with the chorus of birds. All alone she had stood there at the bus shelter, with the sun reflected in his old aviator sunglasses she had nagged him to give her, even though they covered half her face. She had waved, possibly. Maybe even blown a kiss. She used to do that.

The young policeman had been wearing similar sunglasses. He pushed them up on to his head as he stepped into the hall and fixed his eyes on Lelle and Anette.

‘Your daughter didn’t get on the bus this morning.’

‘That can’t be right,’ Lelle said. ‘I dropped her off!’

The police officer shrugged and his pilot sunglasses slipped.

‘Your daughter wasn’t on the bus. We’ve spoken to the driver and the passengers. No one has seen her.’

They had looked at him knowingly, even then, the police officers and Anette. He could feel it. The reproach in their eyes pierced him and all his strength oozed away. After all, he was the last person to see her. He was the one who had given her the lift, the one who was responsible. They asked the same detestable questions over and over again, wanting to know the exact time he’d left her and how Lina was feeling that morning. Was she happy at home? Had they quarrelled?

In the end it got too much for him. He had grabbed one of the kitchen chairs and hurled it fiercely at one of the officers, a spineless bastard who raced out and called for backup. Lelle could still feel the cool, wooden floor against his cheek as they held him down and fastened the cuffs, still hear Anette crying as they took him away. But she hadn’t come to his defence. Not then, not now. Their only child was missing and she had no one else to blame.

Lelle started the engine and reversed the car away from the solitary bus shelter. Three years had passed since she stood there, blowing him kisses. Three years, and he was still the last person to have seen her.

Meja would have stayed forever in that triangular room if it hadn’t been for the hunger pangs. She could never escape the hunger, wherever they lived. She kept one hand on her stomach to silence it as she pushed open the door. The stairs were so narrow she practically had to walk down them on tiptoe, and some of them creaked and groaned under her weight. It was useless trying to be quiet. There were no lights on in the empty kitchen. The door to Torbjörn’s bedroom was shut. The dog lay stretched out beside it, watching her guardedly as she passed. When she opened the front door it got to its feet and slipped out between her legs before she had time to react. It lifted its leg by the lilac bush and then made a few circles in the long grass with its nose to the ground.

‘Why did you let the dog out?’

Meja hadn’t seen Silje sitting in a camping chair against the wall. She was smoking a cigarette and wearing a flannel shirt Meja didn’t recognize. Her hair was like a lion’s mane around her head and it was plain from her eyes that she hadn’t slept.

‘I didn’t mean to, he slunk past.’

‘It’s a bitch,’ Silje said. ‘Her name’s Jolly.’

‘Jolly?’

‘Uh-huh.’

The dog reacted when it heard its name and was soon back on the veranda. It lay down on the dark wood with its tongue out like a tie and gazed at them. Silje held out the packet of cigarettes and Meja noticed she had red marks round her neck.

‘What have you got there?’

Silje gave a lopsided smile.

‘Don’t pretend to be stupid.’

Meja took a cigarette, although she would have preferred food. She hoped Silje would spare her the details and squinted towards the forest. She thought something was moving about among the trees. There was no chance she would ever set foot there. She drew on the cigarette and felt that suffocating feeling again, like being locked in and surrounded.

‘Are we really going to live here?’

Silje dangled one leg over the armrest, showing her black underwear. She jiggled her foot impatiently.

‘We’ve got to give it a chance.’

‘Why?’

‘Because we haven’t got a choice.’

Silje wasn’t looking at her now. The shrillness and euphoria in her voice had gone, her eyes were matt, but her voice was determined.

‘Torbjörn’s got money. He’s got a house and land, a steady job. We can live well here without worrying about next month’s rent.’

‘A run-down shack in the middle of nowhere isn’t what I call living well.’

Red streaks flared up on Silje’s neck and she put a hand over her collarbone as if to control them.

‘I can’t cope any more,’ she said. ‘I’m sick and tired of being poor. I need a man to look after us and Torbjörn is willing to do just that.’

‘You sure of that?’

‘What?’

‘That he’s willing?’

Silje grinned.

‘I’ll make sure he’s willing, don’t you worry.’

Meja crushed the half-smoked cigarette under her shoe.

‘Is there anything to eat?’

Silje inhaled deeply and smiled as if she meant it.

‘There’s more food in this old shack than you’ve seen in your entire life.’

Lelle was woken by his mobile vibrating in his pocket. He was sitting in a sunlounger beside the lilac bushes and he could feel his body aching as he put the phone to his ear.

‘Lelle? Were you asleep?’

‘Shit, no,’ Lelle lied. ‘I’m out here working in the garden.’

‘Are there any strawberries yet?’

Lelle threw a glance at the overgrown patch.

‘No, but they’re well on their way.’

Anette’s breathing was loud on the other end, as if she were trying to compose herself. ‘I’ve put the information on the Facebook page,’ she said. ‘About the memorial service on Sunday.’

‘Memorial…?’

‘For the third anniversary. You can’t have forgotten.’

The chair creaked as he stood up. A wave of dizziness made him reach for the veranda railing.

‘Of course I haven’t bloody forgotten!’

‘Thomas and I have bought candles and Mum’s sewing group have had some T-shirts printed. We thought we’d start at the church and walk together to the bus shelter. Perhaps you can prepare something, in case you want to say a few words?’

‘I don’t need to prepare. Everything I want to say is here inside my head.’

Anette sounded weary as she replied: ‘It would be good if we could show a united front, for Lina’s sake.’

Lelle massaged his temples.

‘Are we going to hold hands, too? You, me and Thomas?’

A deep sigh reverberated against his ear drum.

‘I’ll see you Sunday. And Lelle?’

‘Yeah?’

‘You’re not out driving at night again, are you?’

He rolled his eyes up to the sky, where the sun was hiding behind the clouds.

‘See you Sunday,’ he said and rang off.

It was 11.30. He’d had four hours’ sleep outside in the sunlounger. That was more than he usually got. He scratched the back of his head and saw blood under his fingernails from the mosquito bites. Inside, he put on some coffee and rinsed his face in the sink. He dried himself with the fine linen tea towel and could almost hear Anette’s protest break the silence. Tea towels were for china and glass, not unshaven human skin. And it was the police who should be looking for Lina, not her obsessed father. Anette had slapped him full in the face and screamed that it was his fault; he was the one who should have made sure she got on the bus; he was the one who had taken her daughter away from her. She had hit and clawed at him before he managed to grab her arms and hold her as hard as he could until her muscles relaxed and she crumpled under him. The day Lina disappeared was the last time they touched each other.

Anette looked for answers outside, turned to friends and psychologists and newspaper reporters. To Thomas, the occupational therapist who stood ready and waiting with open arms and a throbbing erection. A man who was willing both to listen and screw away the problem. Anette self-medicated with sleeping tablets and sedatives, which took the focus from her eyes and made her talk too much. She created a Facebook page dedicated to Lina’s disappearance, organized meetings and gave interviews that made the hairs on his arms stand on end. The most intimate details of their life together. Details about Lina that he hadn’t wanted anyone to know.

As for him, he spoke to nobody. He didn’t have time. He had to find Lina. Searching was the only thing that mattered. The trips along the Silver Road began that summer. He lifted the lid of every rubbish bin and dug his way through skips and marshes and disused mines with his bare hands. He sat at home with his computer, reading long threads on internet forums where total strangers discussed their theories about Lina. A long, sickening tangle of suggestions: she had run away, been murdered, kidnapped, dismembered, lost her way, drowned, run over, forced into prostitution, and a whole catalogue of other nightmare scenarios he could hardly bear to think about, but made himself read anyway. On an almost daily basis he rang the police and yelled at them to do their job. He didn’t eat or sleep. He would come home after long days and nights on the Silver Road with his clothes dirty and scratches on his face that he couldn’t explain. Anette stopped asking. Maybe he was relieved she had left him for Thomas, so that he could devote himself to the search. The search was all he had.

Lelle took his coffee to the computer. Lina smiled at him from the screen saver. The air in the room was heavy and stale. The blinds were down and dust whirled in the light that seeped in between the slats. A half-dead pot plant drooped on the windowsill. Everywhere sorrowful reminders of his decline, of what he had become. He logged into Facebook and saw the post about Lina’s memorial service. One hundred and three people had liked it and sixty-four had registered to attend. Lina, we miss you and will never give up hope, one of her friends had written, followed by exclamation marks and crying emojis. Fifty-three people liked this comment. Anette Gustafsson was one of them. Lelle wondered if she was ever going to change her surname. He went on clicking, past poems and photos and angry comments. Someone knows what happened to Lina, time you stepped forward and told the truth! Angry, red-cheeked emojis. Ninety-three likes. Twenty comments. He logged out. Facebook only made him depressed.

‘Why can’t you get involved on social media?’ Anette used to nag him.

‘Get involved in what? A virtual pity-party?’

‘It actually concerns Lina.’

‘I don’t know whether you’ve noticed, but my focus is on finding Lina, not grieving for her.’

Lelle sipped his coffee and logged into Flashback. Nothing new had been added to the thread about Lina’s disappearance. The last entry was dated December the previous year and was from a user with the name ‘truth seeker’.

The police need to check out the HGV drivers using the Silver Road that morning. Everyone knows it’s a serial killer’s favourite job, just take a look at Canada and the USA. People disappear every day on the highways over there.

All one thousand and twenty-four contributors to the Flashback forum seemed touchingly unanimous in their belief that Lina had been picked up and abducted by someone driving a vehicle before the bus arrived. The same theory as the police, in other words. Lelle had phoned round couriers and haulage companies, asking which drivers had passed through the area at the time of Lina’s disappearance. He’d even met some of them for coffee, searched their vehicles and given their names to the investigation team. But none of them seemed to be a suspect and no one had seen anything. The police didn’t like his persistence. This was Norrland, not America. The Silver Road wasn’t a state highway. No serial killers lurked there.

He got up and began rolling up the sleeves of his shirt. It reeked of smoke. He stood facing the map of northern Sweden and peered at the cluster of pins blooming across the interior. He took another pin from the desk drawer and punctured the map yet again, to mark the place where he had been the night before. He wouldn’t give up until every millimetre was covered, until every strip of road and dead-end track and despoiled forest clearing was turned inside out.

He moved a blood-stained fingernail over the map, hunting for the next obscure track to investigate. He saved the coordinates on his mobile and reached for his keys. He had wasted enough time already.

Silje’s eyes had that glint of mania, as if all of a sudden everything was possible, as if a run-down house in a forest was the answer to her prayers. Her voice rose a couple of octaves, becoming clear and melodious. Words tumbled out of her, as if there wasn’t enough time to say everything that needed saying. Torbjörn seemed to be enjoying it. He sat in contented silence as Silje raved on, saying how happy she was with him and his family home, how she loved everything from the patterned vinyl flooring to the huge floral design of the curtains. Not to mention nature, the way they were surrounded by it. Just what she’d dreamed of all these years. She made a big show of getting out her easel and paintbrushes, swore she would do her best work, thanks to the exceptional light of the summer nights. It was here in the fresh air that her soul would find rest, it was here she could really be creative. This new ecstasy made her overly demonstrative. Her frenzied outbursts had to be emphasized with kisses and strokes and long hugs, all of which sent fear surging down Meja’s backbone. This mania was always the beginning of some fresh new hell.

On the second evening the medication went in the bin. Half-empty blister packs stared up at Meja through the potato peelings and coffee grounds. Powerful tablets in harmless pastel shades. Small chemical miracles which could ward off both the insanity and the darkness, and keep a person alive.

‘Why have you binned your medication?’

‘Because I don’t need it any longer.’

‘Who says you don’t need it? Have you talked to your doctor?’

‘I don’t have to talk to a doctor. I know myself that I don’t need it any more. Out here I’m in my element. Now, finally, I can be who I really am. The darkness can’t reach me here.’

‘Can you hear yourself?’

Silje gave a peal of laughter.

‘You worry too much. You should learn to relax, Meja.’

Through the long, luminous nights Meja lay staring at her backpack, which was still full of all her things. She could steal some money and get the train back south, stay with friends while she looked for work. Go to social services for help if it came to that. They knew what Silje was like, how destructive she could be. But she knew she wouldn’t do it. She had to keep an eye on Silje, who had become full of platitudes.

I’ve never breathed such fresh air before!

Isn’t this silence wonderful?

But Meja didn’t experience any silence. Quite the reverse: the forest was full of sounds that drowned out everything else. Night time was worst, with the whining mosquitoes and twittering birds, and the wind rushing and howling, making the spruces curtsey. Not to mention the sounds from downstairs. Shrieking and panting and phony voices. Mostly Silje, naturally. Torbjörn was a more reserved kind of person. Not until they had gone quiet did Meja dare go down to the kitchen, when only the sound of Torbjörn’s snoring echoed through the room, to drink up the dregs of Silje’s wine. The wine was the only thing that helped against the light.

Lelle didn’t sleep in the summertime. Not any more. He blamed the light, the sun that never set, that filtered through the black weave of the roller blind. He blamed the birds that chirped all night long and the solitary mosquitoes that buzzed above him as soon as his head hit the pillow. He blamed everything apart from what was really keeping him awake.

His neighbours were seated on their patio, laughing, their cutlery clinking. He ducked to avoid them seeing him as he walked towards the car. He rolled down the driveway as far as he could before turning on the engine, just so they wouldn’t hear. But he was pretty sure the neighbours knew that he disappeared in the evenings, that they saw his Volvo glide over the gravel at the very quietest time of night. The whole village was quiet as he passed, houses silent and glowing in the midnight sun. He passed the school where he worked, although he’d been on leave so much in the past few years he could barely call himself a teacher any more. As he came closer to the bus shelter his pulse began to pound in his temples. There was a hopeful little devil inside him that expected to see Lina there, arms crossed, waiting, exactly as when he had left her. Three years had passed, but that damned bus shelter still haunted him.

The police had a theory that someone who was travelling the Silver Road had pulled up at the bus stop and abducted Lina. Either the person had offered her a lift or forced her into the vehicle. There were no witnesses to support that theory, but it was the only explanation. How otherwise could she have disappeared so fast and without trace? Lelle had dropped Lina off at about 5.50. The bus had arrived fifteen minutes later, according to the bus driver and the passengers, and by then Lina wasn’t there. It was a fifteen-minute window. No more than that.

They had gone through the whole of Glimmersträsk with a fine-tooth comb. Everyone had joined in the search. They had dragged every lake and river and formed human chains that walked for miles in every direction. Dogs and helicopters and volunteers from the whole county had helped in the search. But no Lina. They never found her.

He refused to believe she was dead. For him she was just as much alive now as she was that morning at the bus stop. Sometimes he was asked questions by scavenging reporters or tactless strangers.

Do you think your daughter is alive?

Yes, I do.

Lelle had time to smoke three cigarettes during the thirty-minute drive up to Arvidsjaur. The petrol station was closing as he walked in. Kippen was mopping the floor, facing the other way. His bald head shone under the fluorescent lights. Lelle tiptoed to the coffee machine and filled a disposable mug to the brim.

‘I was just wondering where you’d got to.’

Kippen leaned the heavy bulk of his body on the mop.

‘I made fresh coffee especially for you.’

‘Cheers,’ said Lelle. ‘How’s it going?’

‘You know, can’t complain. You?’

‘Still breathing.’

Kippen took the money for the cigarettes. He didn’t charge Lelle for the coffee and handed him a day-old cinnamon bun in a bag. Lelle broke off a dry corner, which he dunked in his coffee as Kippen returned to his mopping.

‘You’re out driving tonight, I see.’

‘Yep, I’m out driving.’

Kippen nodded and looked sad.

‘The anniversary is almost here.’

Lelle looked down at the wet floor.

‘Three years. Sometimes it feels like it was yesterday, and sometimes it feels like a whole lifetime has passed.’

‘And what are the police doing?’

‘I wish I bloody knew.’

‘Surely they haven’t given up?’

‘Nothing much happens, but I’m keeping the pressure up.’

‘That’s good. I’m here if ever you need any help.’

Kippen dipped the mop into his bucket and wrung it out. Lelle balanced the bun on his coffee mug, shoved the cigarettes into his pocket and patted Kippen’s shoulder with his free hand on the way out.

Kippen had been there from the beginning. In the days after the disappearance he had gone through the petrol station’s CCTV footage, covering the hours before and afterwards to see if there was any trace of Lina. If she had been given a lift or been snatched by someone there was a possibility the person had stopped to fill up. They hadn’t found anything, but Lelle had the feeling that Kippen never stopped checking, even after all this time. He was a rare friend, someone to treasure.

Lelle sat behind the wheel again and dipped the last piece of his bun in the coffee, studying the desolate pumps as he ate. He had calculated how far Lina’s abductor could have driven if he’d had a full tank when she was taken from Glimmersträsk. Depending on the car, they could have driven further into the mountains, maybe all the way to the Norwegian border. If they’d stayed on the Silver Road, that is. It was also possible they had turned off on to smaller, rarely used roads without traffic or houses. They hadn’t realized until the evening that she was missing, of course. That was more than twelve hours later. So the kidnapper or kidnappers had been given a good head start. He wiped his hands on his jeans, lit a cigarette and turned the key in the ignition. He left Arvidsjaur behind and was alone with the forest and the road, winding down the window so he could breathe the smell of the pines. If trees could speak, there would have been thousands of witnesses.

The Silver Road was the main artery that linked him to a wide network of smaller veins and capillaries that pumped through the countryside. There were overgrown timber tracks, snowmobile trails and well-worn paths that wound their way between abandoned villages and shrunken communities. There were rivers and lakes and sour little streams that flowed both above and below ground, steaming marshes that spread out like weeping sores, and bottomless, black-eyed tarns. Searching for a missing person in this kind of terrain was a lifetime’s work.

There were vast distances between communities and between people travelling here. On the few occasions a car overtook him his heart would hammer, almost as if he expected to see Lina through the rear window. He stopped at remote lay-bys and lifted the lids of the rubbish bins, as so many times before, his heart in his mouth as if it were the first time. He would never get used to it. Just before Arjeplog he turned off on to one of the smaller capillaries, a road that was no more than two tyre tracks running between the firs. Lelle smoked without taking his hands off the wheel. Veils of mist drifted like spectres among the trees and he squinted through the faint light to get a better idea of where he was. The track was too narrow to turn around, and if he wanted to go back he would have to reverse. But these days Lelle wasn’t the kind to reverse. The Volvo had to bump over the scrubby undergrowth, while ash flickered down the front of his shirt. He pressed on until he glimpsed the first building between the tree trunks, a disintegrating house up to the windowsills in brushwood. Where there had once been windows and doors there were now gaping holes. Further down the road another wooden skeleton was being consumed by the forest, and then another. Decaying homes where no one had lived for decades. Lelle stopped the car in the middle of this desolation and sat for a long while before filling his lungs with air and taking the Beretta from the glove compartment.

Meja had learned to keep out of the way of Silje’s men. She avoided being alone in the same room as them, because she knew it was seldom only Silje they wanted. They liked to press up against her, slap her backside, give her breasts a small, sly nip. It had been like that even before she’d had any breasts to nip.

But Torbjörn would never touch her. She realized that the third evening after their arrival, when she came down to the kitchen and found him alone, slurping coffee from his saucer. She slipped past him as quietly as she could and went out to the veranda as if she hadn’t seen him. Meja had only just lit a cigarette when he stuck out his head and asked her if she wanted a late snack. The skin on his face was creased and she realized he was older than she thought, considerably older than Silje. Old enough to be her grandfather.

He disappeared back inside and she could hear him whistling as he smoked. She kept her eyes on the forest, mainly to hold it back from her. She couldn’t understand how anyone would live like this of their own free will. Disturbing rustlings came from under the spruce branches where the shadows danced. A smell of mould rose up from the veranda, and the dog’s claws clicked against the greying wood when it came out and lay at her feet, so close she could feel its rough coat under her toes. From time to time it lifted its head and looked towards the forest, as if it had heard something deep inside there. Meja felt her heart contract every time. Finally, she couldn’t stand it any longer. The stranger in the kitchen was better than all the things she couldn’t see.

Torbjörn had laid the table with coffee cups, bread, cheese and ham.

‘I don’t have anything else.’

Meja hesitated in the doorway, glanced at the room where Silje was sleeping, and then at the food.

‘Bread’s fine.’