8,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Salt

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Shortlisted for the Portico Prize 2012. Gloria, meet Stephen. He's your dead brother's best friend. He's also a liar, and he doesn't want to hand over your brother's belongings. He's got a hair collection, and he's got somebody's teeth hidden in a drawer. An inconvenient spider's going to play a crucial part in your relationship. Oh yes, and someone – God knows who – is sending him letters claiming it's his fault Max is dead. Stephen, meet Gloria. She's not good with people. She wants you to hand over all Max's most precious stuff. She likes to steal things, she gate-crashes funerals, she's going to force you to revisit some of the most painful moments in your life. And she doesn't know who's writing the weird letters you're getting, but she tends to agree – she thinks it might be your fault her brother killed himself. Oh yes, and it's down to her that you're going to wind up in hospital, and all over the papers. Well, the Scarborough papers anyway. On the plus side – you might get to sleep with her. You're going to be together for one strange, eventful and occasionally horrifying week so … good luck.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

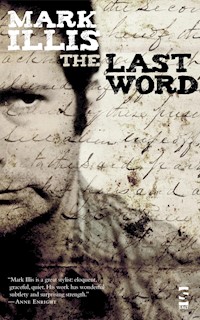

The Last Word

Shortlisted for the Portico Prize 2012

Gloria, meet Stephen. He’s your dead brother’s best friend. He’s also a liar, and he doesn’t want to hand over your brother’s belongings. He’s got a hair collection, and he’s got somebody’s teeth hidden in a drawer. An inconvenient spider’s going to play a crucial part in your relationship. Oh yes, and someone — God knows who — is sending him letters claiming it’s his fault Max is dead.

Stephen, meet Gloria. She’s not good with people. She wants you to hand over all Max’s most precious stuff. She likes to steal things, she gate-crashes funerals, she’s going to force you to revisit some of the most painful moments in your life. And she doesn’t know who’s writing the weird letters you’re getting, but she tends to agree — she thinks it might be your fault her brother killed himself. Oh yes, and it’s down to her that you’re going to wind up in hospital, and all over the papers. Well, the Scarborough papers anyway. On the plus side — you might get to sleep with her.

You’re going to be together for one strange, eventful and occasionally horrifying week so . . . good luck.

Praise for Mark Illis

‘Mark Illis is a great stylist: eloquent, graceful, quiet. His work has wonderful subtlety and surprising strength.’ —Anne Enright

‘On Tender: Illis has an engaging style and his prose is vivid and inventively colloquial.’ —Times Literary Supplement

‘On Tender: Tender can mean loving. But in this coolly observed, meticulously crafted family drama, one is reminded that it also means damaged, and acutely vulnerable to further hurt.’ —The Independent

The Last Word

Mark Illis had three novels published by Bloomsbury before he was 30. He’s now one of Salt’s bestselling authors. He’s been writing for TV for 15 years and has had several radio plays broadcast.His stories have been published in many magazines and anthologies. Born in London, he now lives in West Yorkshire with his wife and two children.

Also by Mark Illis

Tender (Salt)

A Chinese Summer (Bloomsbury)

The Alchemist (Bloomsbury)

The Feather Report (Bloomsbury)

Published by Salt Publishing Ltd

12 Norwich Road, Cromer, Norfolk NR27 0AX

All rights reserved

Copyright © Mark Illis, 2011, 2013

The right of Mark Illis to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Salt Publishing.

Salt Publishing 2011, 2013

Created by Salt Publishing Ltd

This book is sold subject to the conditions that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

ISBN 978 1 84471 977 8 electronic

For Dean

Contents

Thursday

Departure

Paint

Friday

Boundaries

Arrival

Saturday

The Max Museum

Human Watching

Box

Sunday

About Jude

Story of a Spider

Monday

Close

About Rachel

Tuesday

Humans Meeting

SStory of a Hero

Wednesday

Margin

Thursday

Last Words

Thursday

Departure

The news cameby phone. He asked if he was talking to Gloria. I said yes. He said, ‘Gloria Rumat?’ I said yes. He said he was Stephen, calling from England, and he had bad news. His voice was very quiet, and I asked him to speak up. He told me my brother had died. He paused, and so did I. I felt I’d been rattled, picked up and shaken. Silence between us for a few seconds. The soft hush of distance on the phone line, my unsteady breathing. I asked him how Max had died, and he said he’d fallen under a train. Barely audible. I didn’t know if it was him whispering or a fault on the line. I said, ‘Did he fall or did he jump?’ Stephen murmured that he fell.

My mother always hated the phone. She seldom answered it, said it was an intrusion, no better than someone bellowing at you through your letterbox. That was my first thought, my hand still resting lightly on the receiver. There was an image in my head of Stephen crouching outside my front door, shouting quietly. Then I started to feel loose and liquid. I slopped from one side of the flat to the other, stared out of the window, sat down and looked for a long time at my knees. The textures of things attracted my fingers. They moved slowly over the cushion beside me. Small soft bristles, moving backwards and forwards. I stood abruptly, went to the kitchen and hovered somewhere behind my shoulder, watching myself find a mug, a teabag. I put them down, held on to the counter and gripped it, weeping.

Then the process of leaving. The big, thin-walled space of the airport, the feeling of unburdening when my bag was checked in, all the journeys swimming around me, about to start. Through Passport Control, through the spindly door-frame of the metal detector, and into the Departure Lounge.

I bought a coffee, sat at a plastic table, watched the monitor. Wait in lounge. I’d spent a year in Hong Kong, but it felt like I’d arrived the previous week, and the intervening time had been compressed into a few days. Teaching English, going to the races, sailing in the harbour, brief trips into mainland China, meeting Clara. I sipped coffee, scratched at a brown stain on the dimpled surface of the table. It felt like everywhere I’d been was the Departure Lounge. A comfortable space, with food-stops and things to do, but not a destination, not a settled place.

Scratching the stain had left brown stuff under my fingernail, dried coffee. I used the stirrer to dislodge it, then scratched some more. I’d met Clara at the races soon after I arrived. She’d come up and asked my advice on a horse. I told her I had no idea. She looked a bit taken aback by my tone; not angry, just puzzled. Usually I’d have walked away, but I found myself feeling sorry. Perhaps it was her puzzlement, perhaps the unlikely white cardigan she was wearing. I said I preferred cats to horses. She stared at me a second, then laughed, and we made a bet together, then had a drink together, and soon found that we’d spent the day together.

Without noticing what I was doing, I’d scratched an M into the stain on the table. M for Max. I studied the letter until it was just a shape, a house with the roof fallen in, then finished my soapy coffee. No one in miles of where I was sitting knew I was bereaved. That didn’t seem right. The businesswoman at the next table pressed a key on her laptop and gave a satisfied grunt. She was wearing a sleeveless red top and her left hand was stroking her temple. She looked like she belonged in an advert. I felt like tapping her on the shoulder, telling her my brother had just died.

I stared at her, then stood, went over, and tapped her on the shoulder.

She looked up, a frown falling across her face. ‘Yes?’

I hesitated. Saw the wariness in her eyes as she gauged how much trouble I was going to be.

‘Nothing. Sorry.’

I returned to my table. Watched the monitor.

Clara came round soon after the phone call. ‘Jesus, Gloria,’ she said, and hugged me. I smelt her hair, felt her jumper against my cheek, let her keep her arms tight round me while I shed some tears on her shoulder.

She took me out and we wandered for a while, found ourselves on Nathan Road and visited the jade market, where grinning men tried to push bangles and rings on us. I shook my head, ‘No, no, no thanks,’ like an uneasy tourist again, on her first day on the island. Clara took control, put her arm in mine and took me to a café where she had a bowl of soup and I smoked cigarettes and drank green tea.

I didn’t want to talk about Max, so we talked about my plans instead. How strange it was, after a year in Hong Kong, to be reeled back, across half the world, back to a small town in Yorkshire. I said, ‘I can’t stay in England, I don’t know anyone there.’ She tried to interrupt but I over-rode her. ‘No, I need my life peopled. I like saying I’m having drinks with you on Tuesday, seeing a film with Joe on Friday, going to that club on Saturday. I need it peopled and I need it thing-ed. There’s that thing on Tuesday, another on Friday, and that thing on Saturday. I can’t stay in England, I can’t be where I don’t know anyone.’

I had a feeling I might be gabbling. If I was Clara I’d have been tempted to slap me, but she was calmly finishing her soup, tipping a morsel of crab meat on to her spoon. I was grateful to her. In every area where I floundered she was competent. She wasn’t very good at boyfriends or clothes, but in the adult areas of life she excelled. Her work was well paid and had prospects; she had cultivated a social life; she thought about the future; and now it seemed she knew how to cope with a bereaved friend.

‘You’ll meet people in England,’ she said, slow and unruffled. ‘You shouldn’t come straight back. You should stay.’

This was an old argument. I’d told her many times that I made friends rarely, and flukily. ‘I won’t meet anyone,’ I said. ‘I’m terrible at meeting people.’

The stain had almost gone, just a ghost of an outline left, and a little pile of flaky brown matter. Still twenty minutes to spend in the Lounge. I felt already out of Hong Kong, but not yet anywhere else.

I found a seat near another monitor. In the next row a Chinese man was sitting erect, looking sombrely into space. Wrinkled brown skin, brown suit, black tie. He had an urn on his lap. I stared. An urn? Surely there’d be rules about that sort of thing. Was he going to carry ashes on his lap in the plane? It was a cream-coloured, curvy little urn, plastic, I thought. If you were in a supermarket, you’d expect it to contain a milkshake.

Casual but direct, I approached, hovered, and sat down beside him. The tulip seat sloped, cupping my hips. After a moment, I glanced down at his lap, and held the look, hoping for a spontaneous reaction from him, to ease me into conversation. Ah, I see you’re looking at my urn. Something like that. He kept gazing elsewhere. Normally, I’d have left him to it. Normally, I’d have felt he had a right to his privacy, but at this moment I felt we were members of a club. That was the spirit, camaraderie, not nosiness.

I was about to speak, on the brink of it, when, with a little wet sound from inside his mouth, he stood up suddenly and marched off. I stood up too, angry, about to follow and grab his shoulder — How dare he? I stopped myself. I watched him walk on, not knowing I’d moved, and then I sat down again, casual, as if nothing had happened. I was furious with myself. I hadn’t wanted to upset him, I just wanted to talk to somebody who might understand. Perhaps I’d email Clara about it later. See? Terrible at meeting people.

I was probably better on my own anyway, because this was a natural point to start thinking about Max, this quiet point after all the hasty business of the last few days. But I didn’t. Didn’t think about Max. My hand lay on my bag, as if I was protecting it. Snubbed, touching my bag, people-watching, I sat there, not really in Hong Kong, but not yet anywhere else. Breathing in and breathing out, fast and shallow, as if I’d recently finished a race.

And now the monitor said I had two hours to wait. Moments ago, it was twenty minutes. What had happened to time?

Trying to be pragmatic and calm, I reviewed my itinerary. If my flight was not further delayed I would just make it to the funeral, jet-lagged and ragged, at midday on Friday. Then, Clara had said, I’d probably need some time to ‘sort things out’ before I came back. Who knows, she’d said, maybe I’d decide to stay.

‘No,’ I insisted. ‘There’s the life I’ve got here — some friends, a job, everything I need. Or there’s England — no friends, no job, no Max. I like it here, I like it here, I like it here.’ I was slapping the table in front of me. Bereavement seemed to have made me more emphatic.

‘OK.’ Clara’s tone was gentle, like she was soothing an anxious pet. ‘I’m just saying, you’re a bit at the edge of things here, and this could be an opportunity.’

‘I hate opportunities. Everything’s fine, and then an opportunity comes along and you have to think about changing it all. Maybe I like being at the edge of things. Have you thought of that?’

‘Do you?’

‘Of course not.’

I look at people who aren’t at the edge of things, who confidently occupy the centre, and I admire them. Like Clara, working at the bank and earning a stash of money to take back to England in her planned and sensible way. Navigating a steady path through her life. When I look at her, I feel precarious.

An hour had passed, it was already past midnight, but the monitor now told me I had three more hours to wait. Time was definitely acting up. I looked at my watch, made some calculations. I was tired and disorientated, it wasn’t easy to work out the maths, but it was pretty obvious that I was going to miss Max’s funeral.

I’m going to miss my brother’s funeral. The thought started to buzz in my head. I felt raw, and tender. Might they hurry everything up, if I told them about Max? I imagined a delay caused by terrorists, frantic behind-the-scenes activity, a bomb, things flying apart. The whole airport felt unsolid, it was easy to imagine it all floating away in pieces.

I climbed on my seat. It was something to do with wondering if I could see the gate from where I was, or even the plane. There was nothing different to see except the tops of heads, but I stayed there, as people started to stare. It gets on my nerves when people stare, so puzzled or worried by any rupture in the normal way things happen. I wanted to shout: ‘I’m going to miss my brother’s funeral!’ but I didn’t. I just stood there, on my seat, until eventually people looked away, realising that nothing exciting was going to happen. Then I stood there some more, to make it clear I wasn’t being intimidated. Then I sat down.